Abstract

An important measure of cardiovascular health is obtained by evaluating the global cardiovascular risk, which comprises a number of factors, including hypertension and type 2 diabetes, the leading causes of illness and death in the world, as well as the metabolic syndrome. Altered immunity, inflammation, and oxidative stress underlie many of the changes associated with cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome, and recent efforts have begun to elucidate the contribution of PGE2 in these events. This review summarizes the role of PGE2 in kidney disease outcomes that accelerate cardiovascular disease, highlights the role of cyclooxygenase-2/microsomal PGE synthase 1/PGE2 signaling in hypertension and diabetes, and outlines the contribution of PGE2 to other aspects of the metabolic syndrome, particularly abdominal adiposity, dyslipidemia, and atherogenesis. A clearer understanding of the role of PGE2 could lead to new avenues to improve therapeutic options and disease management strategies.

Keywords: BP, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, kidney disease, chronic renal failure, chronic renal insufficiency

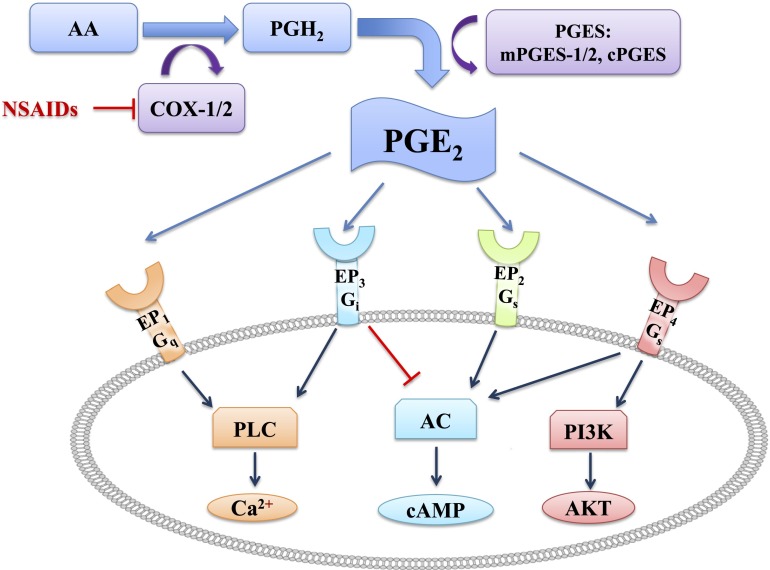

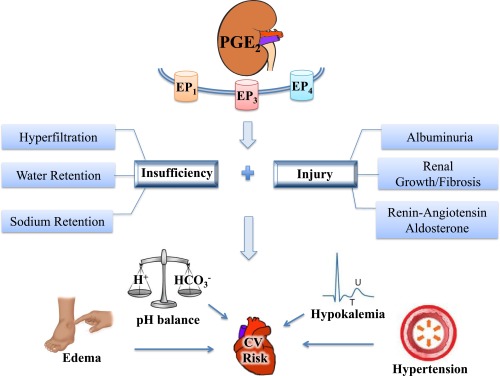

Accelerated cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of mortality in patients with kidney disease.1,2 This implies that kidney disease has a major effect on global cardiovascular risk, affecting fluid (volume, BP), electrolyte, and acid base balance, among many other cardiovascular risk factors. In fact, renal transplantation ameliorates cardiovascular risk, improves quality of life, and reduces mortality.2 PGs are important homeostatic regulators of kidney function. PGE2 is the major product of cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 and microsomal PGE synthase 1 (mPGES1), and both of these enzymes are elevated in renal diseases.3–10 PGE2 binds four EP receptors (EP1–4) to activate G protein signaling responses. Figure 1 illustrates the COX pathway leading to PGE2, as well as its target receptors. These receptors are often coexpressed in cells and usually have opposing effects (protective and harmful). PGE2 acting on EP can alter vascular tone and influence renal blood flow and hemodynamics.11–15 PGE2 also stimulates the macula densa to activate the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, a key mediator of kidney injury.16–19 Inflammatory, immune, and oxidative stress responses are influenced by PGE2, which are reported to alter growth, fibrosis, and apoptosis in renal cells.20–26 PGE2 also contributes to disturbances in collecting duct salt and water transport in polyuric diseases,19,27–29 and β cell defects in sodium and potassium handling associated with type I distal renal tubule acidosis.30 PGE2/EP4 also compensates for the loss of vasopressin V2 receptors in mouse diabetes insipidus.28 Although attempts to block PGE2 using COX-2 or mPGES1 inhibitors have failed, selective inhibition of EP receptors may prove to be quite useful in controlling the deleterious effects of COX-2/mPGES1/PGE2, while leaving the protective responses intact. EP1 mediates many of the pathologic effects of PGE2 in kidney diseases.21 In fact, a lack of EP1 or EP1 antagonism protects against hyperfiltration, albuminuria, and markers of injury in diabetic mouse models21,26 or spontaneously hypertensive mice.31 Our group recently reported that EP1 mediates reactive oxygen species and fibronectin induction in PGE2 stimulated cultured mouse proximal tubules.20 A protective role for EP1 was described in glomerulonephritic mice32 but the reason for this discrepancy is unclear. EP2 is mainly found in vascular and interstitial compartments of the kidney, and EP2 knockout mice develop salt-sensitive hypertension.33 The contribution of EP2 to renal disease is unknown, but it may have a role in cyst formation in polycystic kidney disease.34 EP3 is mainly associated with water balance, mediating pathologic polyuria and tubular injury in postobstructive35 and lithium-induced nephropathies27,36 and diabetes insipidus.37 Our group confirmed that EP3 contributes to diabetic dysfunction and injury in mice, including hyperfiltration, hypertrophy, polyuria, and albuminuria (unpublished data). The protective nature of EP4 was demonstrated in EP4 null mice subjected to unilateral ureteral obstruction, with augmented fibrosis and inflammatory/fibrotic markers of injury.38 PGE2/EP4 also maintains podocyte integrity and reduces the onset of proteinuria in diabetes,23 and EP4 agonism was beneficial in 5/6 nephrectomy.39 EP4 is also harmful in other studies; for instance, EP4 antagonism prevented abnormalities in epithelial proliferation and chloride transport associated with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.40 In addition, EP4 agonism promoted glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis in diabetes.41 Clearly targeting EP receptors may be advantageous in the treatment or prevention of kidney disease outcomes, but more work is needed to clarify the controversies and gain insight into the precise contribution of each receptor subtype. Figure 2 illustrates the contribution of PGE2/EP to kidney disease processes (insufficiency and injury) that affect cardiovascular risk.

Figure 1.

PGE2 synthesis and signaling pathways. AA is released by phospholipase A2 (PLA2) from membrane phospholipids and converted into PGH2 by COXs (COX-1/COX-2). COX activity is inhibited by NSAIDs. PGE2 is produced by PGE synthase (mPGES-1, mPGES-2, and cPGES), and signals by binding to its G protein–coupled receptors EP1– EP4. Activation of EP1 (coupled to Gq) increases intracellular Ca2+ via phospholipase C (PLC). Activation of EP3 (coupled to Gi) increases intracellular Ca2+ via PLC and/or inhibits cAMP production via adenylate cyclase (AC). Activation of EP2 or EP4 (both coupled to Gs) stimulate cAMP production via AC. Activation of EP4 also increases protein kinase B (AKT/PKB) via stimulation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K). Arrowheads indicate stimulations, whereas blunt ends indicate inhibition.

Figure 2.

PGE2 contributes to renal insufficiency and injury leading to increased cardiovascular (CV) risk. PGE2 acting on EP1, EP3, and EP4 contributes to renal disease processes causing insufficiency (hyperfiltration, altered water, and salt transport) and injury (albuminuria, growth/fibrosis, activation of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone). Overall, this may prevent or promote CV risk factors, including altered potassium homeostasis and pH balance as well as hypertension and edema. Hyperfiltration, albuminuria, and consequent loss of systemic oncotic pressure would lead to edema, and salt and water retention could be contributing factors. PGE2 could affect sodium and water retention directly, or indirectly via activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, which leads to volume expansion, hypertension, potassium loss, and hypokalemia. Mechanisms of pH balance are also dependent on renal transport properties. Renal growth and fibrosis are major factors that cause renal injury and contribute to renal insufficiency, thereby increasing the risk of developing CV disease.

PGE2 in Hypertension and Diabetes

Inappropriate immune responses, chronic low-grade inflammation, and oxidative stress are important in the development and progression of target organ damage associated with both hypertension and diabetes.42 A comprehensive listing of the various systemic and metabolic factors involved (environmental/genetic, immune, sympathetic nervous system, and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system), their complex interplay, and cardiovascular consequences that arise have been thoroughly reviewed.43 Despite their obvious involvement, strategies to halt the mediators of these pathogenic mechanisms remain unsuccessful at managing disease progression. Because COX-2/mPGES1/PGE2/EP receptors are implicated in many of the disturbances associated with diabetes and hypertension, many efforts are aimed at deciphering the exact role, to identify alternate targets for therapy.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) inhibit COX, and mostly have hypertensive effects, especially with prolonged use (recently reviewed by Khatchadourian et al.44). This response depends on the relative selectivity for each COX isoform, but both chronic high-dose ibuprofen (nonselective) and celecoxib (COX-2 inhibitor) increased systolic BP in diabetic mice.5 However, deoxycorticosterone acetate–salt hypertension was attenuated in mice lacking mPGES1, which otherwise displayed a 5-fold increase in PGE2 levels.45 The mechanisms were not fully explored but seem to be associated with oxidative stress responses in the kidney. PGE2 is an important modulator of BP, acting at various levels (central and peripheral responses, renal hemodynamics, and salt and water balance). Yang and Du46 provide an intricate overview of the PGE2/EP pathways that act both centrally and peripherally to elicit hypertensive and hypotensive effects. We recently reviewed the role of renal PGE2/EP receptors in the development of hypertension, affecting renal hemodynamics, renin release, and salt and water transport in the nephron.47 Overall PGE2 is an important antihypertensive agent under basal conditions, because of its potent diuretic and natriuretic roles in the kidney mediated by all four EP receptors47 as well as its systemic depressor effect mediated by EP2, which predominates in basal states.33 In the absence of this depressor response, a pressor effect of EP3 was revealed. EP3 is also implicated in the central regulation of BP, stimulating sympathetic responses.46 Moreover, pulmonary hypertension was attenuated in mice lacking EP3 receptors.48 It had long been recognized that prostacyclin analogs are beneficial in pulmonary hypertension, but their use is limited by the presence of vasoconstrictor EP3. Accordingly, antagonizing EP3 may prove useful in preventing vessel injury and remodeling in response to chronic hypoxia. Better control of PGE2-mediated BP effects would be achieved by directly targeting EP-specific responses. In addition to conventional regulators of BP, new evidence of a more complex nature is emerging, with mechanisms involving the skin, the gut and mouth microbiome, and dietary nitrates in hypertension.49–56 Future exploration of these avenues may unveil novel roles for PGE2.

Hypertension is more prevalent in patients with diabetes, causing target organ damage, especially cardiovascular and renal vascular disease. The associated decline in cardiovascular health accounts for >80% of the mortality.43,57 In addition to cardiovascular disease, the three major microvascular complications of diabetes are retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy. The main trigger is hyperglycemia, with microvascular alterations contributing to progressive injury, but many vasoactive substances are also involved. PGE2, as a major product of COX-2, clearly plays an important role in the end organ damage associated with diabetes. Diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause of blindness and has been associated with a number of injurious responses, with inflammation and oxidative stress as the main features.58 COX-2 has long been implicated in the retinal damage associated with diabetes.59–65 In the earliest stages of streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rodents, COX-2 and PGE2 are elevated and COX-2 inhibitors reduce injurious responses to many pathogenic factors, like TNF-α66 and vascular endothelial growth factor.60,67 Although the mechanism appears to involve various second messengers (extracellular-regulated kinases, protein kinase A or C, NFκB), the nature of COX-2, PGE2, and EP receptor involvement is poorly understood. A pilot study using the COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib to treat diabetic macular edema was inconclusive as a result of a small study group and short duration of the intervention.58 A more elaborate trial is needed to ascertain the benefits of COX-2 inhibition in preventing blindness owing to macular edema in patients with diabetes. Interestingly, EP3 has been implicated in ischemic retinopathy by inhibiting thrombospondin 1 and cluster of differentiation 36.68 However, EP2 protects against retinal ischemia reperfusion–induced angiogenesis by stimulating neuronal nitric oxide synthase and choline acetyltransferase,69 whereas EP4 promotes vascular endothelial growth factor–mediated neovascularization in cultured Müller cells.70 A better characterization of the specific EP pathways would certainly yield better intervention possibilities in early diabetic retinopathy.

Diabetic neuropathy is another common microvascular complication of diabetes, consisting of progressive nerve dysfunction and damage due to altered blood supply, oxidative stress, and inflammatory injury. A wide range of symptoms arise as a result of the diabetic injury, ranging from an exaggerated perception of sensory stimuli to spontaneous paresthesias and pain, features of both allodynia and hyperalgesia. Recently published studies provide an elaborate review of the pathophysiology underlying the neuropathic pain71 as well as the detailed mechanisms triggered by hyperglycemia leading to nerve injury.72 Although hyperglycemia is central to the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy, a number of metabolic and vascular factors are involved. Most of the available therapies are symptomatic, including antidepressants, anticonvulsants, topical anesthetics, opioids, and other analgesics. NSAIDs have shown narrow therapeutic benefits,73,74 but more work is needed to ascertain their benefits along with other pharmacological agents.75 As a major inflammatory mediator in the diabetic milieu, COX-2 is implicated in diabetic neuropathy, and a more targeted approach to therapy will certainly prove more effective. Unlike nonselective NSAIDs,76,77 COX-2 inhibitors show promise, with protection against nerve dysfunction and nerve fiber loss78 as well as attenuated mechanical hyperalgesia79 in experimental diabetes. There may be important considerations regarding therapy; for instance, mechanical allodynia was only prevented by inhibiting spinal COX-2 before established symptoms, otherwise the treatment becomes ineffective.80 COX-2 is elevated in three diabetic rat models and may be implicated in tactile allodynia in the rat,65 as well as p38-mediated allodynia in diabetic mice.81 A couple of studies in diabetic rodents indicate that both COX-282 and PGE2 are elevated in hyperalgesic conditions as well, and PGE2 may mediate the bradykinin-induced nociceptor sensitization described in response to hyperglycemic hypoxia in diabetic rats.83 Although PGE2 can also modulate nondiabetic pain responses, contributing to heat- and acid-induced nociceptor sensitization,84,85 more work in this area is warranted to better clarify the role of PGE2/EP responses in diabetic neuropathy.

The best characterized role for COX-2 and PGE2 is related to diabetic nephropathy, contributing to hyperfiltration, growth, fibrosis, apoptosis, and altered transport. A number of detailed reviews describe these events from hyperglycemia to altered renal function and kidney injury.47,86–89 Both COX-2 and PGE2 are consistently elevated in patients with diabetes and in a number of rodent models.5,7–10,21,90–97 Interestingly, despite the many claims that COX-2 mainly couples to mPGES1, a recent study reports that diabetic renal PGE2 production by COX-2 is independent of mPGES1. In fact, diabetic mice lacking mPGES1 were no different than diabetic wild types with respect to albuminuria and other markers of injury. The authors suggest that another as-yet unidentified synthase may mediate PGE2 production by the diabetic kidney.95 Interestingly, in mice with type 2 diabetes, mPGES1 contributed to induction of glomerular PGE2 synthesis, and the peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) agonist rosiglitazone protected against glomerular injury by targeting the mPGES1/PGE2/EP4 pathway. Unfortunately, glomerular COX-2 expression was not directly addressed in this study, but whole-kidney COX-2 was elevated in diabetic mice and was unaffected by rosiglitazone treatment.97 COX-2 inhibitors may display some protection against diabetic injury, but studies are inconsistent.5,90,92,94 As discussed above, a new interest has emerged in specifically targeting EP receptors to better control renal complications in diabetes. Diabetic kidney injury is ameliorated by EP1 antagonism26 and exacerbated by EP4 agonism,41 but the role of EP4 remains controversial. There is undoubtedly a detrimental role of PGE2/EP receptors in diabetic nephropathy, but more work is needed to clarify the exact pathways involved, with many controversies awaiting clarification. Our group recently reviewed the role of each EP receptor in the diabetic changes as well as the potential of EP receptors as therapeutic targets,47 suggesting that overall EP1 antagonists and/or EP3/EP4 agonists may prevent renal injury (reducing growth/apoptosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and fibrosis) and control kidney dysfunction (preventing hyperfiltration, renin secretion, and altered sodium and water transport) in diabetes. A detailed account is beyond the scope of this review.47 However, we have new evidence that EP3 contributes to diabetic dysfunction and injury in mice (unpublished data).

PGE2 in Other Aspects of the Metabolic Syndrome

Obesity is a major factor in the assessment of global cardiovascular risk; like hypertension and diabetes, obesity is reaching epidemic proportions, especially in North America.98 Abdominally distributed adiposity, as measured clinically by waist circumference, is a central component of the metabolic syndrome, both as a direct risk factor and as a contributor to other risk factors such as dyslipidemia, insulin insensitivity, glucose intolerance, and hypertension. The link between obesity and metabolic disturbances leading to diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease was thoroughly reviewed by Sowers.99 The roles of leptin and insulin in controlling the adipose tissue browning process at the level of the hypothalamus were also recently reviewed.100 A better appreciation of peripheral transformation of white-to-brown fat is of great interest, and PPAR-γ is a key regulator of adipose homeostasis, promoting differentiation of both white and brown adipocytes. A regulated coordination between mPGES-1 and PPAR-γ underlies white-to-brown transformations.101 COX-2 is also involved in the recruitment of brown adipocytes to white adipose tissue, but the nature of the PG involved was not identified.102,103 PGE2 is the main PG secreted by adipose tissue, and EP receptors are expressed in adipocytes, mediating its local responses.104,105 EP4 receptors in adipose tissue reduce chemokine production, by inhibiting IFN-γ and macrophage inflammatory protein 1α.106 PGE2/EP3 increases both leptin secretion and lipolysis in rodent adipocytes, and it regulates adipogenesis.107,108 Consistently, mice lacking EP3 display enhanced night eating behaviors and are obese.109 Moreover, PGE2 regulates the transformation of white to beige fat, which protects against obesity and metabolic disease, but whether EP3 is involved remains unclear.101 Although very little is known about all of the EP receptor pathways implicated, PGE2 does inhibit adipogenesis via EP4.110 It is also clear that mPGES-1/PGE2 interact with PPAR-γ, promoting beige adipocyte differentiation in white adipose tissue, which increases energy expenditure and can prevent obesity related comorbidities. Interestingly, the treatment of obesity and related metabolic disturbances by targeting PG reductase-3 (which metabolizes the PPAR-γ ligand 15-keto-PGE2) to limit PPAR-γ–mediated adipocyte differentiation, was reported.111 15-keto-PGE2 is the product of PGE2 oxidization; in chronic diseases characterized by a state of increased inflammation (increased COX2-PGE2) and oxidative stress, this reveals a novel mechanism linking the two environments to regulation of adipogenesis. Therefore, targeting mPGES-1 or specific PGE2 EP receptors may be important therapeutic avenues to explore in the treatment or prevention of obesity.

PGE2 can also increase cardiovascular risk by contributing to atherogenesis. Since the introduction of COX-2 inhibitors into the clinical setting, prothrombotic and atherogenic consequences were discovered, mainly owing to the shifting synthesis of PGs to favor thromboxane and PGE2 while reducing prostacyclin. This same PG profile was observed upon deletion of COX-2.112 COX-2 null mice actually had the same phenotypic consequence as deletion of the prostacyclin IP receptor, with accelerated atherogenesis.113,114 Instead, deletion of vascular mPGES1 limits the atherogenic response and prevents the thrombotic consequences associated with COX-2 selective antagonism.115 A central role was revealed for mPGES1 from myeloid cells to the atherogenic response in inflammatory states, suggesting that it can be targeted to protect against cardiovascular consequences.116 The role of COX-2 in the inflammatory response is controversial and it appears that timing is everything, with a dual role as a producer of proinflammatory and proresolving mediators in acute inflammation.117 PGE2 plays a central role in the nonresolving inflammatory state associated with the formation of atherosclerotic lesions, and all three EP receptors are somehow implicated in the formation and stabilization of the atherosclerotic lesion. In fact, statins protect against thrombotic events by inhibiting COX-2/mPGES1/PGE2/EP–mediated instability of carotid plaques, and the expression of EP1, EP3, and EP4 receptors is reduced by atorvastatin in both the plaques and mononuclear cells of patients with carotid atherosclerosis.118 EP3 is highly expressed in platelets and is involved in platelet activation119; EP3 null mice displayed increased bleeding times and were less prone to developing thromboembolisms.120 PGE2 acting on EP2 and EP4 reduces human platelet hyper-reactivity, which is associated with increased cardiovascular risk,121 and was shown to inhibit mouse platelet aggregation.122

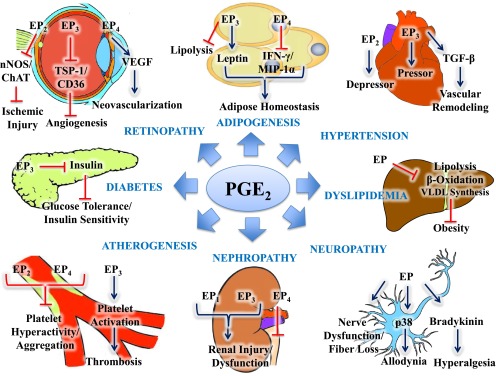

PGE2 also contributes to dyslipidemia and insulin resistance.42,123,124 PGE2 acting on EP3 mainly has antilipolytic effects in adipose tissue of both obese and diabetic mice,108,125,126 although mice lacking EP3 are obese.109 More work is needed to clarify this contradiction. Interestingly, in diet-induced obesity in rats, rather than PGE2 from adipocytes, macrophage-derived PGE2 via EP3 signals adipocytes to reduce lipolysis, thereby contributing to abdominal adiposity and associated metabolic disturbances (insulin sensitivity, glucose intolerance, and cardiovascular abnormalities).127 In this regard, PGE2 also inhibits liver lipolysis, β-oxidation, and very low density lipoprotein synthesis further contributing to obesity,128 yet the EP receptor is unknown. This lipid-accumulating effect of PGE2 on hepatocyte lipid metabolism has been recognized for quite some time129–134; however, it has also been demonstrated that PGE2 derived from nonparenchymal liver cells attenuates insulin responses in the hepatocyte.124 COX-2 derived PGE2 also inhibits pancreatic insulin secretion, and COX-2 inhibitors and EP3 antagonists improved β-cell function in mice, resulting in enhanced insulin release and glucose tolerance after a glucose challenge.135 Kimple et al. also confirmed that EP3 is elevated in the diabetic pancreas and reduces insulin secretion from diabetic islets.136 Clearly, EP3 receptors are involved in many deleterious responses associated with diabetes and the metabolic syndrome, and they prove to be enticing targets for therapeutic interventions. Figure 3 summarizes the contribution of PGE2/EP receptors to hypertension and diabetes, while depicting the plethora of responses linking PGE2 to cardiovascular risk. PGE2 acting on EP receptors has been implicated in hypertension and diabetes, as well as many other aspects of the metabolic syndrome; as such, PGE2 has a great effect on global cardiovascular risk.

Figure 3.

PGE2 affects global cardiovascular risk by contributing to adipogenesis, hypertension, dyslipidemia, neuropathy, nephropathy, atherogenesis, diabetes, and retinopathy. Adipogenesis: PGE2 stimulates leptin production via EP3 contributing to adipogenesis. On the other hand, EP4 inhibits IFN-γ and macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α) in adipocytes, preventing adipogenesis. PGE2 promotes obesity by inhibiting lipolysis in the adipose tissue via EP3. Hypertension: PGE2 is a vasodilator via EP2 and constrictor via EP3. EP3 can also upregulate TGF-β to promote vascular remodeling. Dyslipidemia: PGE2 also inhibits lipolysis, β-oxidation, and very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) synthesis in the liver, but the nature of the EP receptor is unknown. Neuropathy: PGE2 contributes to neuropathy via unknown EP receptors by promoting nerve dysfunction/fiber loss, allodynia (via p38), and hyperalgesia (via bradykinin). Nephropathy: PGE2 contributes to renal injury and dysfunction via EP1 and EP3, whereas EP4 prevents renal injury and dysfunction. Atherogenesis: PGE2 also contributes to atherogenesis whereby EP2 and EP4 inhibit platelet hyperactivity and aggregation. On the contrary, EP3 promotes platelet activation increasing the risk of thrombosis. Diabetes: PGE2 can contribute to diabetes via EP3 by inhibiting insulin secretion leading to impaired glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity. Retinopathy: PGE2 contributes to ocular ischemic injury via EP2 by inhibiting neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT). EP3 contributes to ocular angiogenesis by inhibiting thrombospondin 1 (TSP-1) and CD36 (cluster of differentiation 36). EP4 promotes ocular neovascularization by stimulating vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Arrowheads indicate stimulations, whereas blunt ends indicate inhibition.

The global effect of hypertension, diabetes, and obesity epidemics is immeasurable. COX-2/mPGES1/PGE2/EP receptors affect the global cardiovascular risk, including the development of hypertension, diabetes (retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy), and other aspects of the metabolic syndrome (adipose homeostasis, dyslipidemia, and atherogenesis). PGE2 is clearly implicated in glucose and lipid metabolism, vascular remodeling and injury, as well as nerve fiber dysfunction and injury. Because EP receptors are often coexpressed in the same cells and have opposing effects (protective and harmful), it is more promising to explore selective inhibition of EP receptors to modify disease processes. Although our knowledge of the harmful PGE2 EP receptor pathways is expanding, more concerted research efforts are needed to determine the contribution of each EP receptor in these events. These strategies may prove to be quite useful in controlling the deleterious effects of COX-2/mPGES1/PGE2, while leaving the protective EP receptor–mediated responses intact. A better understanding of the underlying mechanisms can lead to more targeted therapies to shrewdly manage disease outcomes.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) and The Kidney Foundation of Canada (Montreal, Quebec, Canada).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

References

- 1.Massy ZA, Drüeke TB: Magnesium and cardiovascular complications of chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 11: 432–442, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glicklich D, Vohra P: Cardiovascular risk assessment before and after kidney transplantation. Cardiol Rev 22: 153–162, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curiel RV, Katz JD: Mitigating the cardiovascular and renal effects of NSAIDs. Pain Med 14[Suppl 1]: S23–S28, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norberg JK, Sells E, Chang HH, Alla SR, Zhang S, Meuillet EJ: Targeting inflammation: Multiple innovative ways to reduce prostaglandin E₂. Pharm Pat Anal 2: 265–288, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nasrallah R, Robertson SJ, Karsh J, Hébert RL: Celecoxib modifies glomerular basement membrane, mesangium and podocytes in OVE26 mice, but ibuprofen is more detrimental. Clin Sci (Lond) 124: 685–694, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Regner KR: Dual role of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 1 in chronic kidney disease. Hypertension 59: 12–13, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherney DZI, Miller JA, Scholey JW, Bradley TJ, Slorach C, Curtis JR, Dekker MG, Nasrallah R, Hébert RL, Sochett EB: The effect of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition on renal hemodynamic function in humans with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 57: 688–695, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherney DZ, Reich HN, Jiang S, Har R, Nasrallah R, Hébert RL, Lai V, Scholey JW, Sochett EB: Hyperfiltration and effect of nitric oxide inhibition on renal and endothelial function in humans with uncomplicated type 1 diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 303: R710–R718, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cherney DZI, Scholey JW, Nasrallah R, Dekker MG, Slorach C, Bradley TJ, Hébert RL, Sochett EB, Miller JA: Renal hemodynamic effect of cyclooxygenase 2 inhibition in young men and women with uncomplicated type 1 diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F1336–F1341, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nasrallah R, Xiong H, Hébert RL: Renal prostaglandin E2 receptor (EP) expression profile is altered in streptozotocin and B6-Ins2Akita type I diabetic mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F278–F284, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ren Y, D’Ambrosio MA, Garvin JL, Wang H, Carretero OA: Prostaglandin E2 mediates connecting tubule glomerular feedback. Hypertension 62: 1123–1128, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pena-Silva RA, Heistad DD: EP1c times for angiotensin: EP1 receptors facilitate angiotensin II-induced vascular dysfunction. Hypertension 55: 846–848, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison-Bernard LM, Monjure CJ, Bivona BJ: Efferent arterioles exclusively express the subtype 1A angiotensin receptor: Functional insights from genetic mouse models. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F1177–F1186, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schweda F, Klar J, Narumiya S, Nüsing RM, Kurtz A: Stimulation of renin release by prostaglandin E2 is mediated by EP2 and EP4 receptors in mouse kidneys. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F427–F433, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Purdy KE, Arendshorst WJ: EP(1) and EP(4) receptors mediate prostaglandin E(2) actions in the microcirculation of rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F755–F764, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pöschke A, Kern N, Maruyama T, Pavenstädt H, Narumiya S, Jensen BL, Nüsing RM: The PGE(2)-EP4 receptor is necessary for stimulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in response to low dietary salt intake in vivo. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F1435–F1442, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vio CP, Quiroz-Munoz M, Cuevas CA, Cespedes C, Ferreri NR: Prostaglandin E2 EP3 receptor regulates cyclooxygenase-2 expression in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F449–F457, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JA, Sheen MR, Lee SD, Jung JY, Kwon HM: Hypertonicity stimulates PGE2 signaling in the renal medulla by promoting EP3 and EP4 receptor expression. Kidney Int 75: 278–284, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nüsing RM, Treude A, Weissenberger C, Jensen B, Bek M, Wagner C, Narumiya S, Seyberth HW: Dominant role of prostaglandin E2 EP4 receptor in furosemide-induced salt-losing tubulopathy: A model for hyperprostaglandin E syndrome/antenatal Bartter syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2354–2362, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nasrallah R, Hassouneh R, Zimpelmann J, Karam AJ, Thibodeau JF, Burger D, Burns KD, Kennedy CR, Hébert RL: Prostaglandin E2 increases proximal tubule fluid reabsorption, and modulates cultured proximal tubule cell responses via EP1 and EP4 receptors [published online ahead of print]. Lab Invest 10.1038/labinvest.2015.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thibodeau JF, Nasrallah R, Carter A, He Y, Touyz R, Hébert RL, Kennedy CR: PTGER1 deletion attenuates renal injury in diabetic mouse models. Am J Pathol 183: 1789–1802, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamamoto E, Izawa T, Juniantito V, Kuwamura M, Sugiura K, Takeuchi T, Yamate J: Involvement of endogenous prostaglandin E2 in tubular epithelial regeneration through inhibition of apoptosis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cisplatin-induced rat renal lesions. Histol Histopathol 25: 995–1007, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faour WH, Thibodeau JF, Kennedy CR: Mechanical stretch and prostaglandin E2 modulate critical signaling pathways in mouse podocytes. Cell Signal 22: 1222–1230, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zahner G, Schaper M, Panzer U, Kluger M, Stahl RA, Thaiss F, Schneider A: Prostaglandin EP2 and EP4 receptors modulate expression of the chemokine CCL2 (MCP-1) in response to LPS-induced renal glomerular inflammation. Biochem J 422: 563–570, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qian Q, Kassem KM, Beierwaltes WH, Harding P: PGE2 causes mesangial cell hypertrophy and decreases expression of cyclin D3. Nephron, Physiol 113: 7–p14, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makino H, Tanaka I, Mukoyama M, Sugawara A, Mori K, Muro S, Suganami T, Yahata K, Ishibashi R, Ohuchida S, Maruyama T, Narumiya S, Nakao K: Prevention of diabetic nephropathy in rats by prostaglandin E receptor EP1-selective antagonist. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1757–1765, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, Pop IL, Carlson NG, Kishore BK: Genetic deletion of the P2Y2 receptor offers significant resistance to development of lithium-induced polyuria accompanied by alterations in PGE2 signaling. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 302: F70–F77, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li JH, Chou CL, Li B, Gavrilova O, Eisner C, Schnermann J, Anderson SA, Deng CX, Knepper MA, Wess J: A selective EP4 PGE2 receptor agonist alleviates disease in a new mouse model of X-linked nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Clin Invest 119: 3115–3126, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rao R, Zhang MZ, Zhao M, Cai H, Harris RC, Breyer MD, Hao CM: Lithium treatment inhibits renal GSK-3 activity and promotes cyclooxygenase 2-dependent polyuria. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F642–F649, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gueutin V, Vallet M, Jayat M, Peti-Peterdi J, Cornière N, Leviel F, Sohet F, Wagner CA, Eladari D, Chambrey R: Renal β-intercalated cells maintain body fluid and electrolyte balance. J Clin Invest 123: 4219–4231, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suganami T, Mori K, Tanaka I, Mukoyama M, Sugawara A, Makino H, Muro S, Yahata K, Ohuchida S, Maruyama T, Narumiya S, Nakao K: Role of prostaglandin E receptor EP1 subtype in the development of renal injury in genetically hypertensive rats. Hypertension 42: 1183–1190, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahal S, McVeigh LI, Zhang Y, Guan Y, Breyer MD, Kennedy CR: Increased severity of renal impairment in nephritic mice lacking the EP1 receptor. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 84: 877–885, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kennedy CR, Zhang Y, Brandon S, Guan Y, Coffee K, Funk CD, Magnuson MA, Oates JA, Breyer MD, Breyer RM: Salt-sensitive hypertension and reduced fertility in mice lacking the prostaglandin EP2 receptor. Nat Med 5: 217–220, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elberg G, Elberg D, Lewis TV, Guruswamy S, Chen L, Logan CJ, Chan MD, Turman MA: EP2 receptor mediates PGE2-induced cystogenesis of human renal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1622–F1632, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang S, Mitu GM, Hirschberg R: Osmotic polyuria: An overlooked mechanism in diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 2167–2172, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kjaersgaard G, Madsen K, Marcussen N, Jensen BL: Lithium induces microcysts and polyuria in adolescent rat kidney independent of cyclooxygenase-2. Physiol Rep 2: e00202, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nielsen J, Kwon TH, Christensen BM, Frøkiaer J, Nielsen S: Dysregulation of renal aquaporins and epithelial sodium channel in lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Semin Nephrol 28: 227–244, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakagawa N, Yuhki K, Kawabe J, Fujino T, Takahata O, Kabara M, Abe K, Kojima F, Kashiwagi H, Hasebe N, Kikuchi K, Sugimoto Y, Narumiya S, Ushikubi F: The intrinsic prostaglandin E2-EP4 system of the renal tubular epithelium limits the development of tubulointerstitial fibrosis in mice. Kidney Int 82: 158–171, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vukicevic S, Simic P, Borovecki F, Grgurevic L, Rogic D, Orlic I, Grasser WA, Thompson DD, Paralkar VM: Role of EP2 and EP4 receptor-selective agonists of prostaglandin E(2) in acute and chronic kidney failure. Kidney Int 70: 1099–1106, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y, Rajagopal M, Lee K, Battini L, Flores D, Gusella GL, Pao AC, Rohatgi R: Prostaglandin E(2) mediates proliferation and chloride secretion in ADPKD cystic renal epithelia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F1425–F1434, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohamed R, Jayakumar C, Ramesh G: Chronic administration of EP4-selective agonist exacerbates albuminuria and fibrosis of the kidney in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice through IL-6. Lab Invest 93: 933–945, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harcourt BE, Penfold SA, Forbes JM: Coming full circle in diabetes mellitus: From complications to initiation. Nat Rev Endocrinol 9: 113–123, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lastra G, Syed S, Kurukulasuriya LR, Manrique C, Sowers JR: Type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension: An update. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 43: 103–122, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khatchadourian ZD, Moreno-Hay I, de Leeuw R: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antihypertensives: How do they relate? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 117: 697–703, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jia Z, Aoyagi T, Yang T: mPGES-1 protects against DOCA-salt hypertension via inhibition of oxidative stress or stimulation of NO/cGMP. Hypertension 55: 539–546, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang T, Du Y: Distinct roles of central and peripheral prostaglandin E2 and EP subtypes in blood pressure regulation. Am J Hypertens 25: 1042–1049, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nasrallah R, Hassouneh R, Hébert RL: Chronic kidney disease: Targeting prostaglandin E2 receptors. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 307: F243–F250, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu A, Zuo C, He Y, Chen G, Piao L, Zhang J, Xiao B, Shen Y, Tang J, Kong D, Alberti S, Chen D, Zuo S, Zhang Q, Yan S, Fei X, Yuan F, Zhou B, Duan S, Yu Y, Lazarus M, Su Y, Breyer RM, Funk CD, Yu Y: EP3 receptor deficiency attenuates pulmonary hypertension through suppression of Rho/TGF-β1 signaling. J Clin Invest 125: 1228–1242, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bondonno CP, Liu AH, Croft KD, Considine MJ, Puddey IB, Woodman RJ, Hodgson JM: Antibacterial mouthwash blunts oral nitrate reduction and increases blood pressure in treated hypertensive men and women. Am J Hypertens 28: 572–575, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang T, Santisteban MM, Rodriguez V, Li E, Ahmari N, Carvajal JM, Zadeh M, Gong M, Qi Y, Zubcevic J, Sahay B, Pepine CJ, Raizada MK, Mohamadzadeh M: Gut dysbiosis is linked to hypertension. Hypertension 65: 1331–1340, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Machnik A, Neuhofer W, Jantsch J, Dahlmann A, Tammela T, Machura K, Park JK, Beck FX, Müller DN, Derer W, Goss J, Ziomber A, Dietsch P, Wagner H, van Rooijen N, Kurtz A, Hilgers KF, Alitalo K, Eckardt KU, Luft FC, Kerjaschki D, Titze J: Macrophages regulate salt-dependent volume and blood pressure by a vascular endothelial growth factor-C-dependent buffering mechanism. Nat Med 15: 545–552, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Machnik A, Dahlmann A, Kopp C, Goss J, Wagner H, van Rooijen N, Eckardt KU, Müller DN, Park JK, Luft FC, Kerjaschki D, Titze J: Mononuclear phagocyte system depletion blocks interstitial tonicity-responsive enhancer binding protein/vascular endothelial growth factor C expression and induces salt-sensitive hypertension in rats. Hypertension 55: 755–761, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wiig H, Schröder A, Neuhofer W, Jantsch J, Kopp C, Karlsen TV, Boschmann M, Goss J, Bry M, Rakova N, Dahlmann A, Brenner S, Tenstad O, Nurmi H, Mervaala E, Wagner H, Beck FX, Müller DN, Kerjaschki D, Luft FC, Harrison DG, Alitalo K, Titze J: Immune cells control skin lymphatic electrolyte homeostasis and blood pressure. J Clin Invest 123: 2803–2815, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang GH, Zhou X, Ji WJ, Zeng S, Dong Y, Tian L, Bi Y, Guo ZZ, Gao F, Chen H, Jiang TM, Li YM: Overexpression of VEGF-C attenuates chronic high salt intake-induced left ventricular maladaptive remodeling in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 306: H598–H609, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rakova N, Jüttner K, Dahlmann A, Schröder A, Linz P, Kopp C, Rauh M, Goller U, Beck L, Agureev A, Vassilieva G, Lenkova L, Johannes B, Wabel P, Moissl U, Vienken J, Gerzer R, Eckardt KU, Müller DN, Kirsch K, Morukov B, Luft FC, Titze J: Long-term space flight simulation reveals infradian rhythmicity in human Na(+) balance. Cell Metab 17: 125–131, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Doi M, Takahashi Y, Komatsu R, Yamazaki F, Yamada H, Haraguchi S, Emoto N, Okuno Y, Tsujimoto G, Kanematsu A, Ogawa O, Todo T, Tsutsui K, van der Horst GT, Okamura H: Salt-sensitive hypertension in circadian clock-deficient Cry-null mice involves dysregulated adrenal Hsd3b6. Nat Med 16: 67–74, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sowers JR, Epstein M, Frohlich ED: Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease: An update. Hypertension 37: 1053–1059, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chew EY, Kim J, Coleman HR, Aiello LP, Fish G, Ip M, Haller JA, Figueroa M, Martin D, Callanan D, Avery R, Hammel K, Thompson DJS, Ferris FL, 3rd: Preliminary assessment of celecoxib and microdiode pulse laser treatment of diabetic macular edema. Retina 30: 459–467, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Du Y, Sarthy VP, Kern TS: Interaction between NO and COX pathways in retinal cells exposed to elevated glucose and retina of diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R735–R741, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ayalasomayajula SP, Amrite AC, Kompella UB: Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2, but not cyclooxygenase-1, reduces prostaglandin E2 secretion from diabetic rat retinas. Eur J Pharmacol 498: 275–278, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Naveh-Floman N, Weissman C, Belkin M: Arachidonic acid metabolism by retinas of rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Curr Eye Res 3: 1135–1139, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Johnson EIM, Dunlop ME, Larkins RG: Increased vasodilatory prostaglandin production in the diabetic rat retinal vasculature. Curr Eye Res 18: 79–82, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Amrite AC, Ayalasomayajula SP, Cheruvu NP, Kompella UB: Single periocular injection of celecoxib-PLGA microparticles inhibits diabetes-induced elevations in retinal PGE2, VEGF, and vascular leakage. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47: 1149–1160, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun W, Gerhardinger C, Dagher Z, Hoehn T, Lorenzi M: Aspirin at low-intermediate concentrations protects retinal vessels in experimental diabetic retinopathy through non-platelet-mediated effects. Diabetes 54: 3418–3426, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kern TS, Miller CM, Tang J, Du Y, Ball SL, Berti-Matera L: Comparison of three strains of diabetic rats with respect to the rate at which retinopathy and tactile allodynia develop. Mol Vis 16: 1629–1639, 2010 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Joussen AM, Poulaki V, Mitsiades N, Kirchhof B, Koizumi K, Döhmen S, Adamis AP: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs prevent early diabetic retinopathy via TNF-alpha suppression. FASEB J 16: 438–440, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li T, Hu J, Du S, Chen Y, Wang S, Wu Q: ERK1/2/COX-2/PGE2 signaling pathway mediates GPR91-dependent VEGF release in streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Mol Vis 20: 1109–1121, 2014 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sennlaub F, Valamanesh F, Vazquez-Tello A, El-Asrar AM, Checchin D, Brault S, Gobeil F, Beauchamp MH, Mwaikambo B, Courtois Y, Geboes K, Varma DR, Lachapelle P, Ong H, Behar-Cohen F, Chemtob S: Cyclooxygenase-2 in human and experimental ischemic proliferative retinopathy. Circulation 108: 198–204, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Osborne NN, Li GY, Ji D, Andrade da Costa BL, Fawcett RJ, Kang KD, Rittenhouse KD: Expression of prostaglandin PGE2 receptors under conditions of aging and stress and the protective effect of the EP2 agonist butaprost on retinal ischemia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 50: 3238–3248, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yanni SE, Barnett JM, Clark ML, Penn JS: The role of PGE2 receptor EP4 in pathologic ocular angiogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 50: 5479–5486, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schreiber AK, Nones CF, Reis RC, Chichorro JG, Cunha JM: Diabetic neuropathic pain: Physiopathology and treatment. World J Diabetes 6: 432–444, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sandireddy R, Yerra VG, Areti A, Komirishetty P, Kumar A: Neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in diabetic neuropathy: Futuristic strategies based on these targets. Int J Endocrin 2014: 674987, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cohen KL, Harris S: Efficacy and safety of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the therapy of diabetic neuropathy. Arch Intern Med 147: 1442–1444, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Clark CM, Jr, Lee DA: Prevention and treatment of the complications of diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 332: 1210–1217, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kaur S, Pandhi P, Dutta P: Painful diabetic neuropathy: An update. Ann Neurosci 18: 168–175, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ahlgren SC, Levine JD: Mechanical hyperalgesia in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Neuroscience 52: 1049–1055, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Calcutt NA, Chaplan SR: Spinal pharmacology of tactile allodynia in diabetic rats. Br J Pharmacol 122: 1478–1482, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kellogg AP, Wiggin TD, Larkin DD, Hayes JM, Stevens MJ, Pop-Busui R: Protective effects of cyclooxygenase-2 gene inactivation against peripheral nerve dysfunction and intraepidermal nerve fiber loss in experimental diabetes. Diabetes 56: 2997–3005, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Matsunaga A, Kawamoto M, Shiraishi S, Yasuda T, Kajiyama S, Kurita S, Yuge O: Intrathecally administered COX-2 but not COX-1 or COX-3 inhibitors attenuate streptozotocin-induced mechanical hyperalgesia in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 554: 12–17, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Takeda K, Sawamura S, Tamai H, Sekiyama H, Hanaoka K: Role for cyclooxygenase 2 in the development and maintenance of neuropathic pain and spinal glial activation. Anesthesiology 103: 837–844, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cheng HT, Dauch JR, Oh SS, Hayes JM, Hong Y, Feldman EL: p38 mediates mechanical allodynia in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Mol Pain 6: 28, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Freshwater JD, Svensson CI, Malmberg AB, Calcutt NA: Elevated spinal cyclooxygenase and prostaglandin release during hyperalgesia in diabetic rats. Diabetes 51: 2249–2255, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fuchs D, Birklein F, Reeh PW, Sauer SK: Sensitized peripheral nociception in experimental diabetes of the rat. Pain 151: 496–505, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zimmermann K, Reeh PW, Averbeck B: ATP can enhance the proton-induced CGRP release through P2Y receptors and secondary PGE(2) release in isolated rat dura mater. Pain 97: 259–265, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pethö G, Derow A, Reeh PW: Bradykinin-induced nociceptor sensitization to heat is mediated by cyclooxygenase products in isolated rat skin. Eur J Neurosci 14: 210–218, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nasrallah R, Clark J, Hébert RL: Prostaglandins in the kidney: Developments since Y2K. Clin Sci (Lond) 113: 297–311, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Komers R: Renin inhibition in the treatment of diabetic kidney disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 124: 553–566, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ahmad J: Management of diabetic nephropathy: Recent progress and future perspective [published online ahead of print March 6, 2015]. Diabetes Metab Syndr 10.1016/j.dsx.2015.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jia Z, Zhang Y, Ding G, Heiney KM, Huang S, Zhang A: Role of COX-2/mPGES-1/prostaglandin E2 cascade in kidney injury. Mediators Inflamm 2015: 147894, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nasrallah R, Robertson SJ, Hébert RL: Chronic COX inhibition reduces diabetes-induced hyperfiltration, proteinuria, and renal pathological markers in 36-week B6-Ins2(Akita) mice. Am J Nephrol 30: 346–353, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Quilley J, Santos M, Pedraza P: Renal protective effect of chronic inhibition of COX-2 with SC-58236 in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H2316–H2322, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Komers R, Lindsley JN, Oyama TT, Anderson S: Cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibition attenuates the progression of nephropathy in uninephrectomized diabetic rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 34: 36–41, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hirasawa Y, Muramatsu A, Suzuki Y, Nagamatsu T: Insufficient expression of cyclooxygenase-2 protein is associated with retarded degradation of aggregated protein in diabetic glomeruli. J Pharmacol Sci 102: 173–181, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cheng HF, Wang CJ, Moeckel GW, Zhang MZ, McKanna JA, Harris RC: Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor blocks expression of mediators of renal injury in a model of diabetes and hypertension. Kidney Int 62: 929–939, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jia Z, Sun Y, Liu S, Liu Y, Yang T: COX-2 but not mPGES-1 contributes to renal PGE2 induction and diabetic proteinuria in mice with type-1 diabetes. PLoS One 9: e93182, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu Y, Jia Z, Liu S, Downton M, Liu G, Du Y, Yang T: Combined losartan and nitro-oleic acid remarkably improves diabetic nephropathy in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305: F1555–F1562, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sun Y, Jia Z, Liu G, Zhou L, Liu M, Yang B, Yang T: PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone suppresses renal mPGES-1/PGE2 pathway in db/db nice. PPAR Res 2013: 612971, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.deShazo RD, Hall JE, Skipworth LB: Obesity bias, medical technology, and the hormonal hypothesis: Should we stop demonizing fat people? Am J Med 128: 456–460, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sowers JR: Diabetes mellitus and vascular disease. Hypertension 61: 943–947, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dodd GT, Decherf S, Loh K, Simonds SE, Wiede F, Balland E, Merry TL, Münzberg H, Zhang ZY, Kahn BB, Neel BG, Bence KK, Andrews ZB, Cowley MA, Tiganis T: Leptin and insulin act on POMC neurons to promote the browning of white fat. Cell 160: 88–104, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.García-Alonso V, López-Vicario C, Titos E, Morán-Salvador E, González-Périz A, Rius B, Párrizas M, Werz O, Arroyo V, Clària J: Coordinate functional regulation between microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 (mPGES-1) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) in the conversion of white-to-brown adipocytes. J Biol Chem 288: 28230–28242, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Vegiopoulos A, Müller-Decker K, Strzoda D, Schmitt I, Chichelnitskiy E, Ostertag A, Berriel Diaz M, Rozman J, Hrabe de Angelis M, Nüsing RM, Meyer CW, Wahli W, Klingenspor M, Herzig S: Cyclooxygenase-2 controls energy homeostasis in mice by de novo recruitment of brown adipocytes. Science 328: 1158–1161, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Madsen L, Pedersen LM, Lillefosse HH, Fjaere E, Bronstad I, Hao Q, Petersen RK, Hallenborg P, Ma T, De Matteis R, Araujo P, Mercader J, Bonet ML, Hansen JB, Cannon B, Nedergaard J, Wang J, Cinti S, Voshol P, Døskeland SO, Kristiansen K: UCP1 induction during recruitment of brown adipocytes in white adipose tissue is dependent on cyclooxygenase activity. PLoS One 5: e11391, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Richelsen B, Eriksen EF, Beck-Nielsen H, Pedersen O: Prostaglandin E2 receptor binding and action in human fat cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 59: 7–12, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Børglum JD, Pedersen SB, Ailhaud G, Négrel R, Richelsen B: Differential expression of prostaglandin receptor mRNAs during adipose cell differentiation. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 57: 305–317, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tang EH, Cai Y, Wong CK, Rocha VZ, Sukhova GK, Shimizu K, Xuan G, Vanhoutte PM, Libby P, Xu A: Activation of prostaglandin E2-EP4 signaling reduces chemokine production in adipose tissue. J Lipid Res 56: 358–368, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fain JN, Leffler CW, Bahouth SW: Eicosanoids as endogenous regulators of leptin release and lipolysis by mouse adipose tissue in primary culture. J Lipid Res 41: 1689–1694, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Strong P, Coleman RA, Humphrey PPA: Prostanoid-induced inhibition of lipolysis in rat isolated adipocytes: Probable involvement of EP3 receptors. Prostaglandins 43: 559–566, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sanchez-Alavez M, Klein I, Brownell SE, Tabarean IV, Davis CN, Conti B, Bartfai T: Night eating and obesity in the EP3R-deficient mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 3009–3014, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tsuboi H, Sugimoto Y, Kainoh T, Ichikawa A: Prostanoid EP4 receptor is involved in suppression of 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 322: 1066–1072, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yu YH, Chang YC, Su TH, Nong JY, Li CC, Chuang LM: Prostaglandin reductase-3 negatively modulates adipogenesis through regulation of PPARγ activity. J Lipid Res 54: 2391–2399, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Narasimha A, Watanabe J, Lin JA, Hama S, Langenbach R, Navab M, Fogelman AM, Reddy ST: A novel anti-atherogenic role for COX-2--potential mechanism for the cardiovascular side effects of COX-2 inhibitors. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 84: 24–33, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Egan KM, Lawson JA, Fries S, Koller B, Rader DJ, Smyth EM, Fitzgerald GA: COX-2-derived prostacyclin confers atheroprotection on female mice. Science 306: 1954–1957, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yu Z, Crichton I, Tang SY, Hui Y, Ricciotti E, Levin MD, Lawson JA, Puré E, FitzGerald GA: Disruption of the 5-lipoxygenase pathway attenuates atherogenesis consequent to COX-2 deletion in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: 6727–6732, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wang M, Zukas AM, Hui Y, Ricciotti E, Puré E, FitzGerald GA: Deletion of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 augments prostacyclin and retards atherogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 14507–14512, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chen L, Yang G, Monslow J, Todd L, Cormode DP, Tang J, Grant GR, DeLong JH, Tang SY, Lawson JA, Pure E, Fitzgerald GA: Myeloid cell microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 fosters atherogenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: 6828–6833, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Chen L, Miao Y, Zhang Y, Dou D, Liu L, Tian X, Yang G, Pu D, Zhang X, Kang J, Gao Y, Wang S, Breyer MD, Wang N, Zhu Y, Huang Y, Breyer RM, Guan Y: Inactivation of the E-prostanoid 3 receptor attenuates the angiotensin II pressor response via decreasing arterial contractility. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32: 3024–3032, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gómez-Hernández A, Sánchez-Galán E, Martín-Ventura JL, Vidal C, Blanco-Colio LM, Ortego M, Vega M, Serrano J, Ortega L, Hernández G, Tunón J, Egido J: Atorvastatin reduces the expression of prostaglandin E2 receptors in human carotid atherosclerotic plaques and monocytic cells: Potential implications for plaque stabilization. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 47: 60–69, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gross S, Tilly P, Hentsch D, Vonesch JL, Fabre JE: Vascular wall-produced prostaglandin E2 exacerbates arterial thrombosis and atherothrombosis through platelet EP3 receptors. J Exp Med 204: 311–320, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ma H, Hara A, Xiao CY, Okada Y, Takahata O, Nakaya K, Sugimoto Y, Ichikawa A, Narumiya S, Ushikubi F: Increased bleeding tendency and decreased susceptibility to thromboembolism in mice lacking the prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP(3). Circulation 104: 1176–1180, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Smith JP, Haddad EV, Downey JD, Breyer RM, Boutaud O: PGE2 decreases reactivity of human platelets by activating EP2 and EP4. Thromb Res 126: e23–e29, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kuriyama S, Kashiwagi H, Yuhki K, Kojima F, Yamada T, Fujino T, Hara A, Takayama K, Maruyama T, Yoshida A, Narumiya S, Ushikubi F: Selective activation of the prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype EP2 or EP4 leads to inhibition of platelet aggregation. Thromb Haemost 104: 796–803, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Magid D, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Schreiner PJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB, American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee : Heart disease and stroke statistics--2013 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 127: e6–e245, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Henkel J, Neuschäfer-Rube F, Pathe-Neuschäfer-Rube A, Püschel GP: Aggravation by prostaglandin E2 of interleukin-6-dependent insulin resistance in hepatocytes. Hepatology 50: 781–790, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Jaworski K, Ahmadian M, Duncan RE, Sarkadi-Nagy E, Varady KA, Hellerstein MK, Lee HY, Samuel VT, Shulman GI, Kim KH, de Val S, Kang C, Sul HS: AdPLA ablation increases lipolysis and prevents obesity induced by high-fat feeding or leptin deficiency. Nat Med 15: 159–168, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Duncan RE, Sarkadi-Nagy E, Jaworski K, Ahmadian M, Sul HS: Identification and functional characterization of adipose-specific phospholipase A2 (AdPLA). J Biol Chem 283: 25428–25436, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Iyer A, Lim J, Poudyal H, Reid RC, Suen JY, Webster J, Prins JB, Whitehead JP, Fairlie DP, Brown L: An inhibitor of phospholipase A2 group IIA modulates adipocyte signaling and protects against diet-induced metabolic syndrome in rats. Diabetes 61: 2320–2329, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Henkel J, Frede K, Schanze N, Vogel H, Schürmann A, Spruss A, Bergheim I, Püschel GP: Stimulation of fat accumulation in hepatocytes by PGE₂-dependent repression of hepatic lipolysis, β-oxidation and VLDL-synthesis. Lab Invest 92: 1597–1606, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Hespeling U, Jungermann K, Püschel GP: Feedback-inhibition of glucagon-stimulated glycogenolysis in hepatocyte/Kupffer cell cocultures by glucagon-elicited prostaglandin production in Kupffer cells. Hepatology 22: 1577–1583, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Fennekohl A, Lucas M, Püschel GP: Induction by interleukin 6 of G(s)-coupled prostaglandin E(2) receptors in rat hepatocytes mediating a prostaglandin E(2)-dependent inhibition of the hepatocyte’s acute phase response. Hepatology 31: 1128–1134, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Pérez S, Aspichueta P, Ochoa B, Chico Y: The 2-series prostaglandins suppress VLDL secretion in an inflammatory condition-dependent manner in primary rat hepatocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1761: 160–171, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Enomoto N, Ikejima K, Yamashina S, Enomoto A, Nishiura T, Nishimura T, Brenner DA, Schemmer P, Bradford BU, Rivera CA, Zhong Z, Thurman RG: Kupffer cell-derived prostaglandin E(2) is involved in alcohol-induced fat accumulation in rat liver. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 279: G100–G106, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Mater MK, Thelen AP, Jump DB: Arachidonic acid and PGE2 regulation of hepatic lipogenic gene expression. J Lipid Res 40: 1045–1052, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Björnsson OG, Sparks JD, Sparks CE, Gibbons GF: Prostaglandins suppress VLDL secretion in primary rat hepatocyte cultures: Relationships to hepatic calcium metabolism. J Lipid Res 33: 1017–1027, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Shridas P, Zahoor L, Forrest KJ, Layne JD, Webb NR: Group X secretory phospholipase A2 regulates insulin secretion through a cyclooxygenase-2-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem 289: 27410–27417, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kimple ME, Keller MP, Rabaglia MR, Pasker RL, Neuman JC, Truchan NA, Brar HK, Attie AD: Prostaglandin E2 receptor, EP3, is induced in diabetic islets and negatively regulates glucose- and hormone-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes 62: 1904–1912, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]