Abstract

Voltage-gated ion channels (VGICs) are outfitted with diverse cytoplasmic domains that impact function. To examine how such elements may affect VGIC behavior, we addressed how the bacterial voltage-gated sodium channel (BacNaV) C-terminal cytoplasmic domain (CTD) affects function. Our studies show that the BacNaV CTD exerts a profound influence on gating through a temperature-dependent unfolding transition in a discrete cytoplasmic domain, the neck domain, proximal to the pore. Structural and functional studies establish that the BacNaV CTD comprises a bi-partite four-helix bundle that bears an unusual hydrophilic core whose integrity is central to the unfolding mechanism and that couples directly to the channel activation gate. Together, our findings define a general principle for how the widespread four-helix bundle cytoplasmic domain architecture can control VGIC responses, uncover a mechanism underlying the diverse BacNaV voltage dependencies, and demonstrate that a discrete domain can encode the temperature dependent response of a channel.

Cells shape their electrical activity by controlling ion channel function in response to physical and chemical cues. Voltage-gated ion channels (VGICs) are exquisitely sensitive to transmembrane potential changes by virtue of a voltage-sensor domain that is embedded in the membrane bilayer (Vargas et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2005). Beyond the intrinsic ability to detect transmembrane voltage changes, VGIC superfamily members possess diverse intracellular domains (Yu et al., 2005) that are employed to tune voltage-dependent responses of a particular channel as a consequence of stimuli from signaling molecules (Morais-Cabral and Robertson, 2015; Yang et al., 2015). Although such domains provide a means for chemical cues to influence VGICs, the sensitivity to physical stimuli, such as temperature, in some VGIC superfamily members (Schneider et al., 2014; Vriens et al., 2014), has raised the question about whether there are equivalently specialized domains that can serve as temperature sensors (Bagriantsev et al., 2012; Brauchi et al., 2006; Grandl et al., 2008) or whether thermal responses arise from elements distributed throughout the channel (Chowdhury et al., 2014; Clapham and Miller, 2011). Moreover, despite notable advances in understanding the structures of some VGIC regulatory domains that respond to ligand or regulatory protein modulation (Jiang et al., 2002; Pioletti et al., 2006; Yuan et al., 2010; Zagotta et al., 2003), how conformational changes within these domains impact the channel pore and alter function remains incompletely understood.

Bacterial voltage-gated sodium channels (BacNaVs) share the six-transmembrane VGIC superfamily architecture and bear a four-helix bundle C-terminal cytoplasmic domain (CTD) that terminates in a four-stranded coiled-coil (Irie et al., 2012; Mio et al., 2010; Payandeh and Minor, 2015; Powl et al., 2010; Shaya et al., 2014). BacNaVs display remarkably diverse voltage responses (Payandeh and Minor, 2015; Scheuer, 2014), having activation potentials, V1/2, that span a ~120 mV range (Scheuer, 2014), from −98 mV for NaVAb from Arcobacter butzleri (Payandeh et al., 2012) to +27 mV for NaVSp1 from Silicibacter pomeroyi (Shaya et al., 2014). The structural basis for this wide voltage response range is unknown (Scheuer, 2014). The CTD domain proximal to the channel pore termed the ‘neck’ is the most diverse element (Payandeh and Minor, 2015; Powl et al., 2010; Shaya et al., 2014) and appears to adopt varied degrees of structure in different BacNaVs (Bagneris et al., 2013; Shaya et al., 2014; Tsai et al., 2013). Studies of different BacNaVs indicate that the CTD is important for assembly (Bagneris et al., 2013; Mio et al., 2010; Powl et al., 2010; Tsai et al., 2013) and function (Bagneris et al., 2013; Irie et al., 2012; Shaya et al., 2014; Tsai et al., 2013). Nevertheless, a clear consensus for the mechanism by which the CTD influences channel function and the means by which it might influence the channel pore remains unknown.

Here, we show that the BacNaV CTD has an integral role in controlling channel voltage-dependent behavior and that variation in neck composition and structure cause functional diversity. Moreover, we demonstrate that the neck has a temperature-dependent unfolding transition that is directly coupled to channel opening. These results establish that a discrete ion channel domain can serve as a temperature response element. The BacNaV CTD location is shared with many VGIC superfamily member helical bundle domains (Howard et al., 2007; Paulsen et al., 2015; Uysal et al., 2009 ; Wiener et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2012), including channels not principally gated by voltage. This architectural commonality suggests that the principles uncovered here set a framework for understanding how four-helix bundle CTDs can modulate VGIC superfamily member function.

Results

BacNaV cytosolic domain regulates voltage dependent channel opening

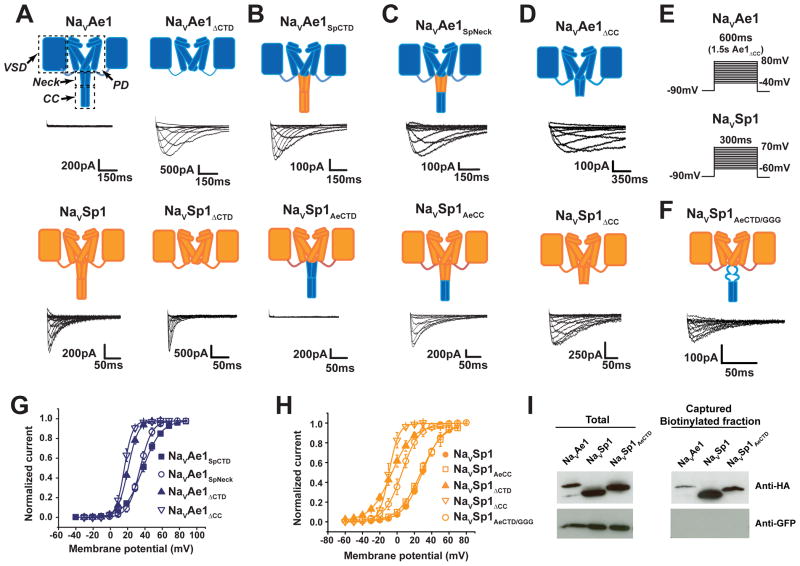

To probe BacNaV CTD function, we focused on two BacNaVs having different activation signatures, Alkalilimnicola ehrlichii NaVAe1 and Silicibacter pomeroyi NaVSp1. NaVSp1 displays robust voltage-dependent activity (Koishi et al., 2004; Shaya et al., 2014), whereas NaVAe1 has not yielded functional data unless neck mutations are present (Shaya et al., 2014) (Figure 1A). We deleted the NaVAe1 and NaVSp1 CTDs at the hinge between the pore module and CTD (ending at NaVAe1 His245 and NaVSp1 His224, respectively (Figure S1A) (Shaya et al., 2014)). Contrary to the loss of function reported for other BacNaV CTD deletions (Mio et al., 2010; Tsai et al., 2013), NaVAe1ΔCTD and NaVSp1ΔCTD produced robust voltage dependent currents, demonstrating that CTD removal did not strongly affect folding or tetramerization (Figure 1A). However, CTD deletion had robust effects on voltage dependent activation, causing large left shifts in V1/2 relative to the references (V1/2 = 19.1 ± 1.9 and 32.1 ± 1.1 mV, for NaVAe1ΔCTD and a functional mutant bearing a neck triple glycine substitution NaVAe1GGG (Shaya et al., 2014), respectively, and −7.4. ± 2.8 and 28.9 ± 1.3, for NaVSp1ΔCTD and NaVSp1, respectively (Figure 1G–H and Table S1)). Thus, CTD deletion produces NaVAe1 and NaVSp1 channels that are more readily opened by voltage.

Figure 1. BacNaV CTD affects function, Related to Figure S1 and Table S1.

Functional comparison of: A, NaVAe1, NaVSp1, NaVAe1ΔCTD, and NaVSp1ΔCTD; B, NaVAe1SpCTD and NaVSp1AeCTD; C, NaVAe1SpNeck and NaVSp1AeCC; and D, NaVAe1ΔCC and NaVSp1ΔCC. Cartoons depict two BacNaV subunits. Voltage-sensor domain (VSD), pore domain (PD), Neck, and Coiled-coil (CC) are labeled. NaVAe1 and NaVSp1 elements are blue and orange, respectively. E, Voltage protocols for NaVAe1 (top), NaVSp1 (bottom), and chimeras. F, NaVSp1AeCTD/GGG exemplar currents. G-H, Voltage-dependent activation curves for: G, NaVAe1, NaVAe1SpCTD, NaVAe1SpNeck, NaVAe1ΔCTD, and NaVAe1ΔCC, and H, NaVSp1, NaVSp1AeCC, NaVSp1ΔCTD, and NaVSp1ΔCC. I, Western blot of the total lysate and surface-biotinylated fraction for the indicated constructs probed using the specified antibodies. See also Figure S1.

The CTD has two parts, the neck (Payandeh and Minor, 2015; Shaya et al., 2014), proximal to the transmembrane pore, and a C-terminal four stranded coiled-coil (Irie et al., 2012; Mio et al., 2010; Payandeh and Minor, 2015; Powl et al., 2010; Shaya et al., 2014). Because CTD deletion had such a strong effect on NaVAe1 and NaVSp1 function, we created a series of chimeras (Figure S1A) to define whether the effects caused by the CTD arise from the neck, coiled-coil, or both. CTD exchange between NaVAe1 and NaVSp1 yielded channels, NaVAe1SpCTD and NaVSp1AeCTD, that phenocopied the properties of the CTD parent; NaVAe1SpCTD was functional (V1/2 = 38.8 ± 2.5 mV) whereas NaVSp1AeCTD showed no activity (Figure 1B and Table S1). Exchanging the NaVAe1 coiled-coil into NaVAe1SpCTD to make an NaVAe1 chimera bearing the NaVSp1 neck and NaVAe1 coiled-coil, NaVAe1SpNeck, produced a channel having voltage-dependent gating that was essentially identical to NaVAe1SpCTD (V1/2 = 32.7 ± 2.0 and 38.8 ± 2.5 mV for NaVAe1SpNeck and NaVAe1SpCTD, respectively) (Figures 1C and 1G, Table S1). Substitution of the NaVSp1 neck into NaVSp1AeCTD produced a NaVSp1 chimera having the NaVAe1 coiled-coil, NaVSp1AeCC that displayed voltage-dependent gating identical to NaVSp1 (V1/2 = 26.1 ± 1.0 and 28.9 ± 1.3 mV, for NaVSp1AeCC and NaVSp1 respectively) (Figures 1C and 1H, and Table S1). Taken together, these results demonstrate that coiled-coil identity has minimal functional effects and that the neck is the principal source of the differences in NaVAe1 and NaVSp1 voltage-dependent behaviors. Although the coiled-coil did not influence channel voltage-dependent properties, it seemed possible that its ability to constrain the neck C-terminal end might be important for the neck to affect gating. Therefore, we examined NaVAe1 and NaVSp1 mutants in which the neck was intact but the coiled-coil was deleted, NaVAe1ΔCC and NaVSp1ΔCC. Both yielded channels having a V1/2 indistinguishable from complete CTD deletion (19.1 ± 1.9 and 17.4 ± 1.7 mV for NaVAe1ΔCC and NaVAe1ΔCTD; −7.4 ± 2.8 and −9.7 ±1.9 mV for NaVSp1ΔCC and NaVSp1ΔCC, respectively) (Figures 1D, G and H, Table S1). Thus, together with the chimera results, these data indicate that the coiled-coil is required to constrain the C-terminal end of the neck, although its identity has minimal effect on function.

Because we were unable to measure currents from NaVAe1 and NaVSp1AeCTD (Figures 1A–B), channels that have a wild-type NaVAe1 neck, we tested whether these proteins had plasma membrane expression to resolve whether the lack of activity came from an absence of surface expression or from channels that could not be opened. We placed an N-terminal hemaggluttinin (HA) tag on NaVAe1, NaVSp1AeCTD, and NaVSp1 and used a surface biotinylation assay to assess plasma membrane expression. Streptavidin capture of the surface-biotinylated fraction followed by anti-HA antibody detection showed clear signals for all three channels. By contrast, this fraction had no signal for the intracellular control, green fluorescent protein, GFP, when probed with an anti-GFP antibody. Thus, the non-functional channels, NaVAe1 and NaVSp1AeCTD, are indeed expressed on the plasma membrane (Figure 1I). Moreover, similar to the effects on NaVAe1 (Shaya et al., 2014), inclusion of a triple-glycine substitution in the neck domain of NaVSp1AeCTD generated a functional channel (NaVSp1AeCTD/GGG V1/2= 5.75 ± 2.6 mV, Figures 1F and H, Table S1). Together with the results of the chimeras and previous neck mutants (Shaya et al., 2014), these findings suggest that NaVAe1 and NaVSp1AeCTD fail to produce currents because the NaVAe1 neck produces a V1/2 that is outside of the measureable voltage range of our experiments.

Our data demonstrate that the CTD functions as a regulatory module whose intrinsic properties enable it to exert diverse effects on BacNaV voltage-dependent gating. The neck influence is strong on voltage-dependent activation and contrasts with its modest effects on voltage-dependent inactivation (Figures 1 and S1B–C, Table S1), a process for which the pore domain is important (Pavlov et al., 2005; Payandeh et al., 2012; Shaya et al., 2014). Thus, our investigations establish that the origins of the dramatic modulation of voltage-dependent gating reside in the neck and require the neck to be constrained at the C-terminal end by the coiled-coil domain.

Diverse BacNaVs CTDs alter NaVSp1 transmembrane domain voltage responses

Prior functional studies reported BacNaV V1/2 activation values spanning a ~120 mV range (Koishi et al., 2004; Payandeh et al., 2012; Ren et al., 2001; Shaya et al., 2014; Ulmschneider et al., 2013). The source of this diversity has been unclear (Scheuer, 2014). Given the profound effects of the CTD on NaVSp1 and NaVAe1, we next asked how replacement of the NaVSp1 CTD with CTDs from previously studied BacNaVs having diverse lengths and compositions would affect function: NaVBh1 (NaVSp1BhCTD), NaVMs (NaVSp1MsCTD), NaVAb (NaVSp1AbCTD), NaVAb1 (Shaya et al., 2011) (NaVSp1Ab1CTD), and NaVPz (NaVSp1PzCTD) (Figures 2A and S1A). In whole cell recordings each of these channels, except NaVSp1AbCTD, was functional (Figure 2B). Strikingly, the CTD substitutions had diverse effects ranging from little change in voltage-dependent activation relative to NaVSp1 for the NaVPz CTD (ΔV1/2 = −4.2 mV) to producing large voltage-dependent activation shifts in both the negative (ΔV1/2 = −44.5 ± 4.4 and −27.3 ± 3.8 mV, NaVBh1 and NaVMs CTDs, respectively) and positive directions (ΔV1/2 = +20.4 ± 5.8 mV NaVAb1 CTD) (Figure 2C, Table S1). For the NaVSp1BhCTD the activation threshold was similar to that of NaVSp1ΔCTD (ΔV1/2 = −44.5 ± 4.4 mV and −36.3 ± 5.4 mV, respectively), a result that is in line with data suggesting that the NaVBh1 neck is disordered (Powl et al., 2010) and the observation that NaVBh1 coiled-coil deletion results in channels having voltage-dependent activation indistinguishable from wild type (Mio et al., 2010). By contrast, the CTD swaps had a more modest effect on voltage-dependent inactivation (Figure S1D, Table S1).

Figure 2. CTD chimeras alter NaVSp1 voltage dependence, Related to Figures S1 and S2 and Table S1 and Table S2.

A, Sequence alignment of NaVAe1, Alkalimnicola erlichii (Shaya et al., 2014; Shaya et al., 2011), NaVSp1, Silicibacter pomeroyi (Koishi et al., 2004; Shaya et al., 2011); NaVAb1, Alcanivorax borkumensis (Shaya et al., 2011); NaVBh1 (NaChBac), Bacillus halodurans (Ren et al., 2001); NaVAb, Arcobacter butzleri (Payandeh et al., 2011); NaVMs, Magnetococcus sp. (McCusker et al., 2012); and NaVPz, Paracoccus zeaxanthinifaciens (Koishi et al., 2004) indicated regions. S6, Neck, Coiled-coil ‘a’–‘d’ positions, and 3G mutation site are indicated. B, NaSp1, NaVSp1BhCTD, NaVSp1MsCTD, NaVSp1Ab1CTD, NaVSp1PzCTD, and NaVSp1AbCTD exemplar currents and voltage protocol. Cartoons depict two channel subunits. C, Activation curves for ‘B’. D, Temperature dependence of NaVSp1 activation. E, V1/2 temperature dependence for the indicated channels. Lines show linear fit.

The varied effects of the different CTD chimeras on the voltage-dependence of the NaVSp1 transmembrane core demonstrate that each BacNaV CTD has a distinct effect on channel activation (Figure 2B) and that a simple BacNaV CTD transplant can tune the voltage-dependence of activation of the transmembrane core over a wide range, ~65 mV (Figure 2C). These results, taken together with the experiments indicating the clear involvement of the BacNaV neck in channel function (Figure 1) and lack of sensitivity to coiled-coil identity (Figure 1C) strongly support a critical role for the neck in BacNaV gating. Although specific elements of the BacNaV transmembrane domains, such as the voltage sensors, must set some of the channel voltage-dependent properties, our findings together with the observation that the neck is the most variable BacNaV feature (Payandeh and Minor, 2015), indicate that much of the observed variety in BacNaV voltage-dependences originates from the neck region. These domains display varied degrees of structure from disordered (Bagneris et al., 2013; Powl et al., 2010) to completely ordered (Shaya et al., 2014). Thus, our data points to a common mechanism for tuning voltage dependencies within the BacNaV family based on the ability of the neck to adopt structure.

Temperature-dependent change in the BacNaV neck affects gating

Previous studies suggested that the neck undergoes an order → disorder transition during channel opening (Shaya et al., 2014) and pose a hypothesis that predicts very different temperature dependences for BacNaVs in which the neck is stably folded structure versus those in which it is disordered. To test this, we first examined whether NaVSp1 voltage-dependent activation was temperature dependent and whether this response could be influenced by neck properties. The V1/2 of NaVSp1 activation showed a clear temperature dependence, moving ~35 mV in the hyperpolarized direction as temperature increased from 18° to 35°C (Figures 2D–E, and Table S2). This response was eliminated by increasing the neck flexibility with a triple glycine substitution, NaVSp1GGG (Shaya et al., 2014), or by CTD deletion, NaVSp1ΔCTD (Figure 2E, Table S2), supporting the idea that neck structure is crucial for temperature-dependent gating changes.

Because the NaVSp1 CTD chimeras displayed diverse activation V1/2 values (Figure 2C), we next probed whether these CTD substitutions affected channel temperature responses. The chimeras having CTDs bearing disordered necks, NaVSp1BhCTD and NaVSp1MsCTD (Bagneris et al., 2013; Powl et al., 2010), yielded channels that lacked a temperature response in activation V1/2 (Figure 2E, Table S2). By contrast, the activation V1/2 of NaVSp1PzCTD and NaVSp1Ab1CTD showed clear temperature dependence. This response was similar in magnitude to NaVSp1 (Figure 2E) and shows that the role of the CTD in setting channel temperature-dependent properties is general.

Finally, we examined whether the V1/2 changes caused by the CTD substitutions were related to neck structure by examining the consequences of neck triple glycine mutations in NaVSp1MsCTD, NaVSp1Ab1CTD, and NaVSp1PzCTD (Figure S2A–B). Neck disruption had no effect on the activation V1/2 for the chimera having a disordered neck, NaVSp1MsCTD (ΔV1/2 = 0.9 mV NaVSp1MsCTD/GGG relative to NaVSp1MsCTD Figure S2C, Table S1). However, for both chimeras having a temperature dependent V1/2 similar to NaVSp1, NaVSp1PzCTD and NaVSp1Ab1CTD, the GGG mutation caused a large activation V1/2 large left-shift (ΔV1/2 = −39.3 and −47.2 mV respectively for NaVSp1PzCTD and NaVSp1Ab1CTD, relative to the parent chimeras, Figure S2D and S2E, Table S1). This magnitude change is similar to that in NaVSp1GGG (ΔV1/2 = −39.4 mV, Fig. S2F, Table S1). Given that the triple glycine mutation eliminates NaVSp1 temperature dependence, these data suggest that the modulatory effects on V1/2 and the temperature dependent gating properties in NaVSp1PzCTD and NaVSp1Ab1CTD arise from neck domain order. Taken together, our data strongly support the hypothesis that a protein unfolding transition in the neck domain is coupled to channel opening and demonstrate that a discrete channel domain can act as a temperature sensor.

Structures of NaVAe1p neck mutants reveal disordered neck and closed pore

To define the structural consequences of polyglycine mutations intended to disrupt the neck, we determined crystal structures of two neck domain mutants of ‘pore-only’ channel NaVAe1p (Shaya et al., 2014), NavAe1p-3G and NavAe1p-7G, at 3.70 Å and 3.80 Å resolution, respectively (Figures 3A–D, Supplementary Figure S3 and Table S3). Molecular replacement using the NavAe1p transmembrane portion (Shaya et al., 2014) yielded maps having well-defined electron density for the transmembrane regions and part of the CTDs (Figures S4A and S4B). Model building and refinement showed traceable density for residues that comprise the neck C-terminal ends and complete coiled-coils (NavAe1p-3G Ile254-Arg283 and NavAe1p-7G Glu257-Arg283)(Figures 3A and B) but lacked density for the polyglycines and residues that frame these substitutions (NavAe1p-3G Ser243-Arg253 and NavAe1p-7G Ser243-Gln256). This localized loss of structure confirms the increase in neck flexibility and shows that the disruption propagates beyond the polyglycines (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. BacNaV neck disruption structural outcomes, Related to Figures S3 and S4, and Table S3.

Cartoons of two subunits of A, NaVAe1p-3G (dark blue) and B, NaVAe1p-7G (firebrick) structures. Grey dashes indicate regions lacking electron density. Residues defining the electron density limits are indicated. Selectivity filter is orange. C, Superposition of NaVAe1p (orange) (Shaya et al., 2014), NaVAe1p-3G (dark blue), and NaVAe1p-7G (firebrick). Angle shows NaVAe1p-7G coiled-coil displacement. Selectivity filter ion positions are shown. D, S6-CTD sequences for the indicated channels. Polyglycine positions are red. Regions lacking electron density are grey. Coiled-coil ‘a–d’ repeat is orange. E, and F, CD spectra for the indicated proteins at 4°C. G, Thermal denaturation curves for the indicated proteins.

Although the NavAe1p-3G and NavAe1p-7G necks lack structure, both CTD coiled-coils remained intact. These were displaced from the channel central axis by ~28° (Figure 3C) and in agreement with its increased disorder, this displacement was larger for NavAe1p-7G and included a ~8Å movement towards the pore (Figure 3C). Once the neck is disrupted, the pore domain and coiled-coil appear to be independent. We anticipate that free from the crystal lattice constraints, the coiled-coil could move independently relative to the pore as solution studies suggest (Bagneris et al., 2013). The fact that the neck disruption does not propagate into the coiled-coil agrees with our observation that coiled-coil identity is not crucial for function but that its presence is essential for the neck to affect function (Figures 1C–D).

Although 3G and 7G substitutions make full length BacNaVs easier to open, NavAe1p-3G and NavAe1p-7G pore domains are closed and match the NaVAe1p closed structure (Figure S4C) (Shaya et al., 2014) (RMSDCα of 0.67 Å and 0.73 Å, respectively). Assignment of a closed conformation is further supported by anomalous difference maps of selenomethionine substituted NavAe1p-3G (Figure S4D and Table S3) that reveal clear density on the pore domain central axis for the seleniums of the activation gate residue, Met241 (Shaya et al., 2014). NaVAe1p-3G, SeMet NaVAe1p-3G, and NaVAe1p-7G structures also revealed density in the selectivity filter ‘site 2’ position (Tang et al., 2014) (Figures S4E–G) that we modeled as a calcium atom based on anomalous density (Figure S4F) and the presence of calcium in the crystallization conditions.

As there is no structure of NavSp1 or the ‘pore–only’ NaVSp1p (Shaya et al., 2011), we turned to circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy to test whether the NaVAe1p-3G and NaVAe1p-7G structural changes had parallels in NavSp1p. NaVAe1p, NaVAe1p-3G, and NaVAe1p-7G CD spectra showed classic helical features of minima at 208 and 222 nm (Berova et al., 2000). Notably, the intensity of these minima was reduced in NaVAe1p-3G and NaVAe1p-7G in an order that matched the crystal structures and was reduced farther by CTD deletion in NaVAe1p-ΔCTD (Figure 3E). Comparison of the CD spectra of NavSp1p (Shaya et al., 2011) with NavSp1p-3G caused a similar loss of helical structure (Figures 3D and 3F). To test whether neck disruption affected the thermal stability, we measured the temperature dependence of the CD signal at 222 nm. The data show that in NaVAe1p introduction of neck region glycines increases the thermal liability of the measured transition following the rank order as expected from the crystal structures (NaVAe1p > NaVAep1-3G > NaVAe1p-7G) (Figure 3G). Notably, NaVAe1p-ΔCTD lacks a cooperative thermal transition, demonstrating that the measured changes in thermal behavior arise from the CTD (Figure 3G). Further, NaVSp1p is less stable than NaVAe1p and the introduction of the triple glycine neck mutant in NaVSp1p eliminated the thermal transition, in agreement with the function of the parent channels (Figures 1 and 2). Together, the crystallographic and CD data demonstrate that increasing BacNaV neck flexibility leads to a loss of structure that is restricted to the neck, show that these changes increase the neck thermal sensitivity, and indicate that this disruption is the source of the functional changes caused by polyglycine substitution.

EPR spectroscopy reveals changes in neck dynamics

To investigate the CTD domain dynamics, we used site specific spin labeling with the nitroxide spin probe (1-Oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrroline-3-methyl) methanethiosulfonate (MTSSL) and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) studies (McHaourab et al., 2011). We probed select positions on the exterior of the NaVAe1p and NaVAe1p-3G CTDs by labeling three neck sites (Glu247 and Ala251 that frame polyglycine sites in NaVAe1p-3G, and Glu255 at the beginning of the NaVAe1p-3G ordered region)(Figures 3A and 4A), three coiled-coil sites (Glu266, Gln269, and Asp273), and a site at the protein C-terminus (Arg283) (Figure 4A). Double electron-electron resonance (DEER) spectroscopy indicated that, with the exception of Arg283, the probe positions in NaVAe1p have spin echo decays with a well-defined oscillation (Figure 4B). The corresponding distance distributions match those expected from the structure (~25Å and ~35Å for adjacent and diagonal nitroxide positions, respectively). By contrast, introduction of triple glycine at residues 248–250 (Figure 4A) caused clear changes at Glu247 and Ala251. These decays showed evidence of superimposed longer component that is manifested in the distance distributions. We interpret this component as indicative of increased disorder (Figure 4B). Notably, minimal changes occurred at Glu255, in complete agreement with the order seen at this site in the crystal structure (Figure 3A). Further, no differences were observed at any coiled-coil positions. Thus, these data reinforce the view from our crystallographic studies that introduction of polyglycine sequences into the neck increase its mobility and spare the coiled-coil structure.

Figure 4. NaVAe1p EPR studies, Related to Figure S5.

A, S6-CTD region sequences. Spin label positions, polyglycine substitutions and, Coiled-coil ‘a–d’ repeat are highlighted green, red, and orange, respectively. NaVAe1p-3G residues lacking electron density are grey. B, NaVAe1p cartoon of two subunits and spin label sites. Pore domain, Neck and Coiled-coil are slate, sand, and orange, respectively, Red and black boxes denote Neck and coiled-coil spin-label positions, respectively. Panels show DEER decays, distance distributions, and CW spectra. Asterisks indicate the new NaVAe1p-3G long-range distances.

There are clear functional differences between NaVAe1 and NaVSp1 that originate in the CTD (Figure 1). Therefore, we probed NaVSp1p at positions equivalent to those tested in NaVAe1p and NaVAe1p-3G (Figure S5) to see whether there was a structural correlate underlying the diverse functional properties. NaVSp1p continuous wave (CW) and DEER studies reveal notable differences in the dynamics of the neck versus the coiled-coil. By contrast to NaVAe1p, the NaVSp1p neck positions consistently display DEER decays that have a longer distance component, similar to those in NaVAe1p-3G, whereas the NaVSp1p coiled-coiled DEER signals resemble what is observed in NaVAe1p (Figure S5B). This differences between EPR probe mobility in the neck and coiled-coil is similar to those observed in NaVMs (Bagneris et al., 2013). Importantly, our data strongly support the notion from the chimera (Figure 2) and CD experiments (Figure 3G) that the neck domains of different BacNaVs have diverse degrees of inherent order and that these differences are the origins of functional diversity.

NaVAe1p neck has a hydrophilic core and a π-stack structure important for gating

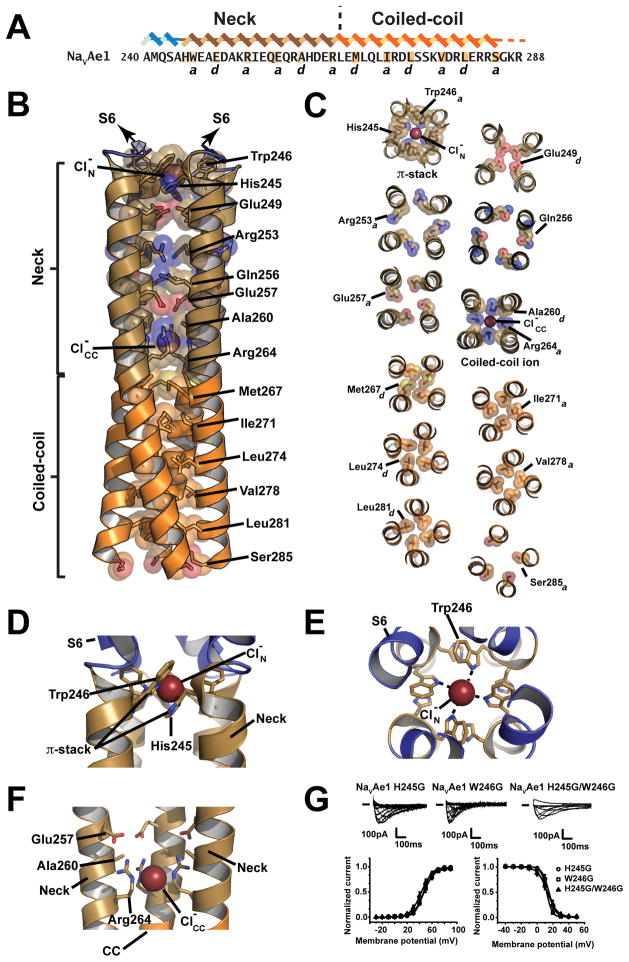

In parallel with our studies of NaVAe1p mutants, we obtained NaVAe1p crystals that diffracted to superior resolution than previously reported (Shaya et al., 2014) (2.95Å vs. 3.46Å, respectively) (Figures S6A and S6B and Table S3). Although the overall architecture is unchanged (Figure S6C), the increased resolution revealed previously uncharacterized CTD features. Notably, there is a striking bipartite organization in the core of the CTD neck and coiled-coil domains. The coiled-coil core follows the classic heptad repeat ‘a-d’ packing (Lupas and Gruber, 2005) (Figures 5A–C) and comprises five layers of hydrophobic residues (Met267, Ile271, Leu274, Val278, and Leu281) and a terminal, more open layer at Ser285 (Figure 5B–C). By contrast, the neck core is composed almost exclusively of hydrophilic sidechains. These also follow a heptad pattern but include a one residue skip at the Gln256-Gln257 junction (Figure 5A). Consistent with the splaying of the neck helices (Shaya et al., 2014), the neck has a less well-packed core than the coiled-coil (Figure 5B–C). The stark differences between the structures and compositions of the neck and coiled-coil cores suggest that the neck is metastable and provide an explanation for why it is able to change structure during channel gating.

Figure 5. NaVAe1p CTD structure, Related to Figures S6 and S7 and Table S3.

A, NaVAe1 sequence. Neck and Coiled-coil ‘a’–‘d’ core residues, His245 and Glu256 are highlighted. B, NaVAe1p CTD cartoon showing core residues. Neck ion, , and Coiled-coil ion, are indicated. S6, Neck and Coiled-coil are slate, sand, and orange, respectively C, NaVAe1p CTD π-stack, ‘a’ and ‘d’ layers, and Coiled-coil ion site packing geometries. D–E, π-stack ion binding site D, Side and E, top views. His245, Trp246, and Neck ion, , are indicated F, Coiled–coil ion binding site. Glu257, Ala260, Arg264, and Coiled-coil ion, are indicated. F, NaVAe1H245G, NaVAe1W246G, and NaVAe1H245G/W246G exemplar currents and voltage-dependence of activation and inactivation. Colors are as in Figure 4.

The 2.95 Å resolution NaVAe1p structure revealed a number of interesting non-protein entities associated with the channel. There are two ions in the CTD core. One is at the N-terminal end of the neck, the ‘neck ion’ (Shaya et al., 2014), and a second is at the neck/coiled-coil junction, the ‘coiled-coil ion’ (Figure 5B). Data collected at the bromine absorption edge from NaVAe1p crystals grown in 200 mM NaBr and soaked in cryoprotectant solutions containing 200 mM or 0 mM NaBr showed strong anomalous densities for both ions in 200 mM NaBr, but only for the coiled-coil ion in 0 mM NaBr (Figure S6D), demonstrating that both CTD ions are halogens and that the neck ion is labile. Based on these observations and the presence of chloride in the 2.95 Å structure crystallization conditions, we modeled both ions as chloride (Figure S6E). The selectivity filter has density corresponding to two sodium ions bridged by a water molecule. One sodium ion occupies the level of the Glu197 sidechain (corresponding to ‘site 2’ (Tang et al., 2014)), and the second is found at the level of Thr195 (‘site 3’) (Figure S6F). We also identified a number of lipids including one occupying a site observed in a number of other BacNaV structures (Payandeh and Minor, 2015) that is located next to the P1 pore helix and wedged between the subunits (Figure S6G).

The neck ion binding site arises from an unusual motif, the ‘π-stack’, in which Trp246 from one subunit makes a face-to-face stacking interaction with His245 from the neighbor (Figures 5B–E) and creates a neck ion binding site coordinated by the Trp246 indole nitrogens. The coiled-coil ion binding site comprises successive ‘a-d-a’ positions in the CTD core (Figures 5B, 5C, and 5F). Four guanido moieties from Arg264 that occupy the first ‘a’ position of the coiled-coil ‘a–d’ repeat coordinate the halide ion (Figure 5F). This ionic complex forms an ‘electrostatic pin’ in the helical bundle core. The Arg264 sidechains extend into the space that should be occupied by the preceding ‘d’ sidechains of the neck core. The presence of a small residue at this position, Ala260, accommodates the Arg264 guanido moieties and permits them to interact with the Glu257 carboxylates from the ‘a’ position above (Figures 5C and 5F). Interestingly, the ‘electrostatic pin’ formed by the coiled-coil ion binding site marks where the CTD helices diverge from the canonical coiled-coil packing. Further, in the NaVAe1p-3G and NaVAe1p-7G structures, disruption of the helical structure propagates through the π-stack but stops at the coiled-coil ion binding site (Figure S6E). These observations agree with the apparent neck and coiled-coil ions binding differences and the metastable nature of the neck hydrophilic core versus the stable coiled-coil hydrophobic core. π-stack and coiled-coil ion motifs signatures occur in other BacNaV sequences and indicate that these structures are present in other channels (Figure S7).

Because the NaVAe1p-3G and NaVAe1p-7G structures showed disrupted π-stack elements due to the polyglycine mutations (Figures 3A–B, 3D, and S6E), we wanted to test whether direct disruption of this structural element would affect function. As with other NaVAe1 neck destabilizing mutations (Shaya et al., 2014), mutation of either π-stack residue to glycine resulted in measurable currents (Figure 5G). As expected from the intersubunit stacking NaVAe1H245G/W246G had essentially identical voltage-dependent activation and inactivation properties compared to NaVAe1H245G and NaVAe1W246G, demonstrating that the two π-stack elements are co-dependent (Figure 5G, Table S1). A previous NaVAe1pH245G low resolution structure showed that π-stack disruption leads to neck ion loss the but little perturbation to the neck helix (Shaya et al., 2014). Thus, theπ-stack architecture serves as a type of lock in the NaVAe1 neck to oppose channel opening.

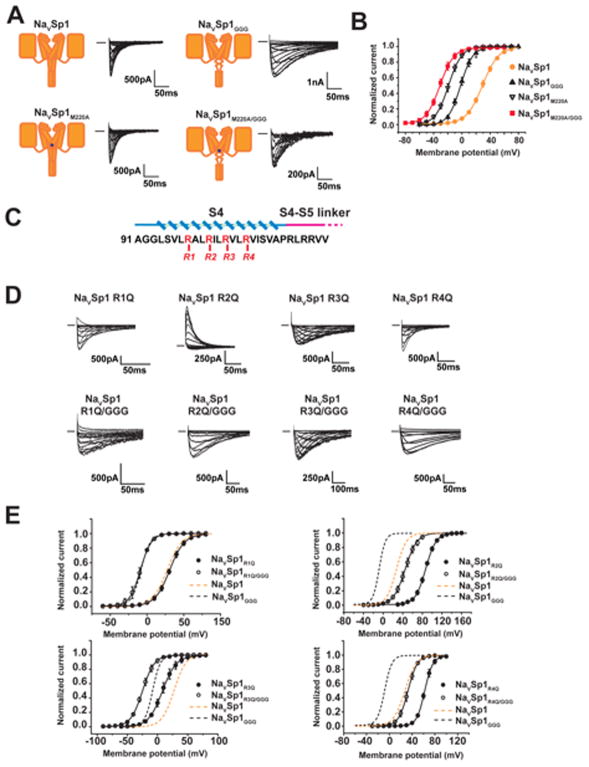

BacNaV neck is energetically coupled to the channel gate

Does the BacNaV neck affect function by impacting the channel gate, the voltage sensors, or both? To answer this question, we pursued a double mutant cycle strategy (DeCaen et al., 2009; Yifrach and MacKinnon, 2002) examining whether NaVSp1 neck by the GGG substitution, NaVSp1GGG, had additive or non-additive effects on voltage gating when placed in the context of mutations that perturb the gate or the voltage sensors. To test whether the neck and gate are coupled, we compared the properties of the NaVSp1 channel gate mutant, NaVSp1M220A (Shaya et al., 2014), NaVSp1GGG, and a channel bearing both mutations NaVSp1M220A/GGG (Figures 6A–B). To probe for coupling to the voltage sensors, we neutralized each of the four arginines at BacNaV S4 voltage sensor positions R1–R4 (Payandeh et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2012) by mutation to glutamine (Figure 6C) in order to perturb the ease of voltage sensor movement and measured the properties of NaVSp1R1Q, NaVSp1R2Q, NaVSp1R3Q, and NaVSp1R4Q, alone and in combination with the GGG neck mutation (Figures 6D–E).

Figure 6. BacNaV CTD couples to the intracellular gate, Related to Table S4.

A, NaVSp1, NaVSp1GGG, NaVSp1M220A, and NaVSp1M220A/GGG exemplar currents. B, Activation curves from ‘A’. C, NaVSp1 S4 mutant sites. D, NaVSp1 R1–R4 and R1–R4/GGG mutant exemplar currents. E, Voltage-dependent activation curves for the indicated mutants. NaVSp1 (tan dashes) and NaVSp1GGG (black dashes) curves are shown for reference.

As observed previously, gate destabilization, NaVSp1M220A (Shaya et al., 2014), and neck disruption, NaVSp1GGG (Shaya et al., 2014), caused substantial leftward shifts in the activation V1/2 (27.7 ± 1.6 mV, −10.5 ± 2.1 mV, and −18.6 ± 2.7 mV for V1/2 of NaVSp1, NaVSp1GGG, and NaVSp1M220A, respectively, Figure 6B, Table S4). Combining both, NaVSp1M220A/GGG, resulted in a V1/2 left shift beyond that of the individual changes (−28.3 ± 4.0 mV, Figure 6B and Table S4). R1 neutralization did not affect the activation V1/2 (31.1 ± 1.2 mV), whereas other arginine position neutralizations shifted the activation V1/2 in either the positive (NaVSp1R2Q, and NaVSp1R4Q, 44.8 ± 2.1 mV and 59.9 ± 3.2 mV, respectively) or negative (NaVSp1R3Q, 11.7 ± 2.3 mV) directions relative to NaVSp1 (Figure 6E and Table S4). In each case, combination with GGG neck mutation caused a substantial left shift in V1/2 (Figure 6E) (NaVSp1R1Q/GGG, NaVSp1R2Q/GGG, NaVSp1R3Q/GGG, and NaVSp1R4Q/GGG, −9.2 ± 1.9 mV, 44.8 ± 2.1 mV, −24.5± 1.8 mV and 32.7± 2.0 mV, respectively).

By taking changes in V1/2, estimated gating charge, Z(e0), and slope factor (k) (DeCaen et al., 2009; Yifrach and MacKinnon, 2002), we determined the activation free energy at 0 mV. Comparison of measured double mutant free energy perturbations relative to NaVSp1 (ΔΔG°obs) with values calculated additive effects of individual mutants (ΔΔG°calc) revealed a clear contrast between how neck perturbation affects the pore and voltage sensors (Table S4). ΔΔG°obs for the neck-gate combination, NaVSp1M220A/GGG, −3.1 kcal mol−1, is substantially less than that expected from the individual (ΔΔG°calc= −5.0 kcal mol−1) (Table S4). By contrast, ΔΔG°obs =ΔΔG°calc for all neck-voltage sensor pairs (Table S4). Thus, these data indicate that the neck affects gating voltage dependence by direct perturbation of the channel gate. Given its location and the importance of neck structure, such an effect must come from the ability of the neck to constrain pore opening.

Discussion

VGIC cytosolic domains are important channel modulation loci. Hence, there is a great interest in understanding how their structural transformations affect VGIC transmembrane channel core. The simple BacNaV CTD architecture, comprising four parallel helices, provides an elegant paradigm for defining how VGIC CTDs can influence channel gating. Our studies of BacNaV CTDs reveal a VGIC modulation mechanism built on the bipartite architecture of the BacNaV CTD four-helix bundle. The key feature, the neck domain, is a membrane proximal four-helix bundle bearing a hydrophilic core that forms a metastable structure. This domain is constrained on its N- and C-termini by the channel pore domain and a classic parallel four-stranded coiled-coil, respectively. These physical constraints are essential for the neck to influence voltage-dependent gating and their importance is supported by two key observations: 1) Deletions of the entire CTD (Figure 1G and H, Table S1) shift the voltage-dependent gating in the hyperpolarized direction in a manner equivalent to deletion of only the coiled-coil (Figure 1, Table S1) and 2) mutant cycle analysis shows strong energetic coupling between the activation gate of the channel pore and the neck (Figure 6, Table S4).

The origin of the wide range of BacNaV voltage-dependent activation responses has been unclear (Scheuer, 2014). The diverse and largely hydrophilic nature of BacNaV neck domains contrasts with the well-conserved CTD coiled-coil and high conservation of key voltage sensor domain elements (Payandeh and Minor, 2015). This neck sequence diversity, together with the capacity of different BacNaV CTDs to tune voltage-responses of the NaVSp1 transmembrane core by >65 mV (Figure 2A–C), indicates that even though features of the transmembrane domains are likely to set some voltage-depending gating properties, much of the varied voltage responses among BacNaVs arises from differences in neck domain properties. These gating effects are directly correlated with the ability of the neck to adopt a stable structure. Studies of chimeras containing the NaVSp1 transmembrane domain and CTDs from other BacNaVs show that channels having the NaVBh1 neck, which is disordered (Powl et al., 2010), have a voltage sensitivity that is equivalent to those lacking the entire CTD (Figures 1H and 2C), whereas those having a completely ordered CTD, NaVAe1 (Shaya et al., 2014), require stronger depolarizations to open. Further, structural and functional studies show that increased neck disorder shifts the activation of both NaVAe1 and NaVSp1 to more hyperpolarized potentials (Figure 3 and (Shaya et al., 2014)). In this regard, our discovery of the ‘π-stack’ halogen-binding site (Figures 5D–E) provides a clear explanation for why NaVAe1, among all other BacNaVs, can only be opened if the neck is destabilized.

Previous deletion studies of different BacNaVs reported varied effects, including a left shift in voltage-dependent activation for NaVSulP (Irie et al., 2012) and no change for NaVBh1 (Mio et al., 2010), and provided no clear view of why there were different outcomes in different channel contexts. Our data now point to a unified mechanism for BacNaV gating in which the CTDs tune the ease of voltage-dependent opening of the channel based on the propensity of the neck region to adopt an ordered state. Due to its high polar residue content, the neck structure is metastable and contrasts with the stable hydrophobic core of the terminal coiled coil. This property is critical for the neck to undergo the order → disorder transition associated with channel opening (Figure 7A). Although CTD mutations can impact channel inactivation properties (Figures S1B–D and (Bagneris et al., 2013; Irie et al., 2010; Irie et al., 2012; Tsai et al., 2013)), the effects are diverse in different BacNaVs and likely reflect a complex inactivation process that also involves key contributions from elements of the pore domain (Pavlov et al., 2005; Payandeh et al., 2012; Shaya et al., 2014). Thus, the clear systemic effects we observe here regarding how neck structure affects activation leads us to propose a gating mechanism in which the order of the neck is directly linked to the ease of channel opening.

Figure 7. Function and structural conservation of VGIC superfamily CTD four-helix bundles, Related to Table S5.

A, BacNaV gating is coupled to a Neck unfolding transition. Purple circles indicate Neck and Coiled-coil ions. B, NaVAe1p (left) and TRPA1 (Paulsen et al., 2015) (right) cartoon diagrams CTD four-helix bundle is indicated. C, NaVAe1p and TRPA1 coiled-coil superposition. TRPA1 shading indicates regions corresponding to the NaVAe1p neck (light grey) and coiled-coil (dark grey). D, Comparison of NaVAe1p (left) and TRPA1 (right) CTD cores. TRPA1 CTD buried hydrophilic residues are Gln1047 and Gln1061. E, NaVAe1p and TRPA1 CTD superhelix radii comparison. Colors are as in ‘C’. See also Table S5.

Our studies revealed two ion binding sites that contribute to CTD functional properties and neck rigidity. The NaVAe1 ‘π-stack’ motif is found in other halophile BacNaVs (Figure S7) and may serve as a point of ion-mediated modulation. The coiled-coil ion binding site comprises an E/Q/D/N/A-A-R motif at successive ‘a’-‘d’-‘a’ positions and is more prevalent among BacNaVs (Figure S7). This structure forms the lower boundary of loss of structure in neck disruptions (Figures 3A–B, and S6E) and provides a structural transition between the hydrophobic core of the coiled-coil and more open, hydrophilic core of the neck. The modular nature of the BacNaV CTD and relatively simple four-helix architecture points towards means to rationally engineer channel responses by controlling the stability of the neck domain using either chimeric approaches or by exploiting stabilizing motifs such as the π-stack.

Some VGIC superfamily members, such as TRPs (Brauchi et al., 2006; Clapham and Miller, 2011; Grandl et al., 2008; Vriens et al., 2014) and K2Ps (Bagriantsev et al., 2012; Lolicato et al., 2014; Maingret et al., 2000; Schneider et al., 2014) are gated by temperature. Whether ion channel temperature dependent responses originate from the action of a single domain (Bagriantsev et al., 2012; Brauchi et al., 2006; Grandl et al., 2008) or a more distributed property (Chowdhury et al., 2014; Clapham and Miller, 2011; Vriens et al., 2014) remains under intense investigation. The NaVSp1 activation V1/2 has a strong temperature dependence (~35 mV over a ~17°C range) that is eliminated by increasing neck disorder (Figure 2D–E). Further, NaVSp1 CTD chimeras having a similar, NaVSp1PzCTD, or more right shifted, NaVSp1Ab1CTD, V1/2 responses also show a strong temperature dependence, suggesting that the activation threshold position coincides with a more structured neck. These acute temperature responses contrast with the <5 mV response of the Shaker voltage-gated potassium channel over a similar temperature range (Chowdhury et al., 2014). Although distributed elements may influence BacNaV temperature responses (DeCaen et al., 2014), particularly in NaVBh1 (NaChBac), which has a disordered CTD (Powl et al., 2010), our data demonstrate that it is possible for a single domain, the BacNaV CTD neck, to control the temperature dependent responses of a VGIC (Figure 2D–E). This result provides a definitive example of a defined temperature-sensing domain.

Structural studies of BacNaVs (Shaya et al., 2014), KCNQ channels (Howard et al., 2007; Wiener et al., 2008), and TRP channels (Paulsen et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2012) establish the commonality of parallel four-stranded coiled-coil domains in the VGIC superfamily. Comparison of the NaVAe1p and TRPA1 CTDs reveals striking similarity well beyond their shared location (Figure 7B–C). Superposition shows a close correspondence in the coiled–coil (Figure 7C–D, Table S5) and highlights NaVAe1p neck helix splaying (Figure 7E). The more uniform TRPA1 coiled-coil has two layers of buried hydrophilic residues: an N-terminal one that matches the position of the NaVAe1p neck and a second one corresponding to the neck:coiled-coil junction (Figure 7C–D). Buried hydrophilic residues in coiled-coil cores carry a well-established energetic penalty with respect to quaternary architecture stability (Lupas and Gruber, 2005). Although TRPA1 ankyrin repeats have been implicated in temperature responses (Cordero-Morales et al., 2011; Jabba et al., 2014), it is striking that they form a cage around the CTD (Figure 7B). Hence, many of the reported ankyrin repeat domain effects may be due to modulation of CTD transitions. It is also notable that the voltage-sensor only channel Hv1 has a similar temperature sensitive membrane proximal coiled-coil domain bearing a buried polar residue in the region implicated in temperature responses (Fujiwara et al., 2012; Takeshita et al., 2014). Thus, the presence of buried polar residues in helical bundle domains in distantly related VGIC superfamily members together with the demonstration that such a metastable domain can play a crucial role in controlling channel function suggests that the mechanism we describe for the BacNaV CTD may occur in many VGIC superfamily members.

Control of ion channel function by physical and chemical cues is essential for producing dynamic changes in excitability (Hille, 2001). While the coupling between the voltage sensor and pore domains has been studied extensively (Lu et al., 2002; Payandeh et al., 2012; Yifrach and MacKinnon, 2002), mechanisms for how cytoplasmic domains modulate the pore remain imperfectly understood. The four-helix bundle architecture of the BacNaV CTD provides a simple means to control channel gating. The metastable, but ordered, neck structure directly couples to the energetics of pore opening (Figure 6). This effect does not depend on voltage-sensor movement and likely affects a late step of channel activation. These observations support the idea conformational changes in such structures can restrain and shape the energetics of channel pore opening (Shaya et al., 2014; Uysal et al., 2009). Consequently, helical bundle domains that bear buried polar residues proximal to a VGIC pore can provide a general mechanism for controlling the action of channels gated by different types of stimuli.

Experimental procedures

Construct design and cloning

NaVSp1 (Silicibacter pomeroyi), NaVAe1 (Alkalilimnicola ehrlichii), chimeras, and mutants were cloned into pIRES2-EGFP vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) (Shaya et al., 2014). Chimeric constructs were generated by PCR. Construct boundaries are found in Supplementary Materials. Mutants were made using QuikChange®(Stratagene). All constructs were verified by complete DNA sequencing.

Patch-clamp electrophysiology

Overexpression and patch-clamp recording from NavSp1, NaVAe1, mutants, and chimeras were performed as described (Shaya et al., 2014). Voltage dependence was analyzed with the Boltzmann equation, y = 1/(1 + exp[(V V1/2)/s]), where y is fractional activation, V is voltage, V1/2 half-activation voltage and s is the inverse slope factor (mV). Details are found in Supplementary Materials.

Surface biotinylation assay

Surface expression was measured in HEK293 cells plated for each HA-tagged construct at 4°C. Samples were analyzed on SDS-PAGE and Western Blot detected. Details are found in Supplementary Materials.

Protein purification and crystallization

NaVAe1p was expressed and purified as described previously (Shaya et al., 2014; Shaya et al., 2011) except that for the size exclusion chromatography step the running buffer included 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM CaCl2, 0.3 mM β-dodecyl maltoside (DDM), 10 mM Na-HEPES, pH 8.0. Constructs for NaVAe1p-3G and NaVAe1p-7G were expressed in Escherichia coli (DE3) C43 (Miroux and Walker, 1996) using a previously described NaVAe1p vector (Shaya et al., 2011). Details of expression, purification, and preparation of selenomethionine labeled NaVAe1p-3G are found in Supplementary Materials.

Crystallization and structure determination

NaVAe1p crystals were grown by hanging drop vapor diffusion. NaVAe1p-3G, NaVAe1p-3G SeMet, and NaVAe1p-7G crystals were grown by microbatch under oil. NaVAe1p, NaVAe1p-NaBr complexes, and NaVAe1p-3G SeMet diffraction data were collected at Advanced Photon Source Beamline 23ID-B, Argonne National Laboratory. NaVAe1p-3G and NaVAe1p-7G diffraction data were collected at Advanced Light Source Beamline 8.3.1, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Details for crystallization, data collection, structure determination, and model refinement can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

CD spectra were recorded on an Aviv 215 spectrometer in a 1 mm pathlength quartz cell at 4 °C. BacNav pore domains were purified as above, exchanged into 10 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 0.3 mM β-DDM, and concentrated to ~24–26 μM. Wavelength scans were recorded in triplicate from 190 to 320 nm with a 1 nm step size averaged over 10s. Thermal melts were as described (Shaya et al., 2011).

EPR labeling and sample preparation

Single cysteine mutants of NaVAe1p, NaVAe1p-3G, and NaVSp1p were generated by quick-change mutagenesis and were purified as above using 1 mM TCEP in all buffers and labeled with MTSSL. CW-spectra were collected on a Bruker EMX at 10 mW power with a modulation amplitude of 1.6G. All spectra were normalized to the double integral. DEER experiments were carried out using a standard four-pulse protocol (Jeschke, 2002). Details can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank and M. Grabe, L. Jan, A. Moroni, and Minor lab members for manuscript comments. This work was supported by grants U54 GM087519 to H.S.M., R01-HL080050, R01-DC007664, and U54-GM094625 to D.L.M., and to C.A. from the American Heart Association. C.A is an AHA postdoctoral fellow.

Coordinates and structure factors are available at the RCSB: NaVAe1p-3G, 5HJ8; NaVAe1p-3G SeMet 5HK6; NaVAe1p-7G. 5HKD; NaVAe1p at 2.95Å, 5HK7; NaVAe1p High Br−, 5HKT; and NaVAe1p Low Br−, 5HKU.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions.

C.A. A.R. and D.L.M. conceived the study and designed the experiments. C.A, A.R., D.S., F.F., R.A.S., S.R.N., and S.M. performed the experiments. C.A. performed electrophysiological experiments and analyzed the data. A.R., D.S., and S.R.N. purified the proteins. A.R. crystallized and determined the structures of polyglycine mutants, performed the CD experiments, prepared EPR samples, and analyzed the data. D.S. grew the NaVAe1p crystals, collected the data, and solved the structure. F.F. solved and refined the structures and analyzed the data. A.R., S.M., and S.A.R. prepared the EPR samples. S.M. and S.A.R. collected the EPR data. H.S.M. supervised the EPR experiments A.R., R.A.S., H.S.M. and D.L.M. analyzed the EPR data. D.L.M analyzed the data and provided guidance and support throughout. C.A, A.R., D.S., F.F., R.A.S. H.S.M., and D.L.M. wrote the paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bagneris C, Decaen PG, Hall BA, Naylor CE, Clapham DE, Kay CW, Wallace BA. Role of the C-terminal domain in the structure and function of tetrameric sodium channels. Nature communications. 2013;4:2465. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagriantsev SN, Clark KA, Minor DL., Jr Metabolic and thermal stimuli control K(2P)2.1 (TREK-1) through modular sensory and gating domains. EMBO J. 2012;31:3297–3308. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berova N, Nakanishi K, Woody RW. Circular Dichroism: Principles and Applications. 2. New York: Wiley-VCH; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brauchi S, Orta G, Salazar M, Rosenmann E, Latorre R. A hot-sensing cold receptor: C-terminal domain determines thermosensation in transient receptor potential channels. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4835–4840. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5080-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S, Jarecki BW, Chanda B. A molecular framework for temperature-dependent gating of ion channels. Cell. 2014;158:1148–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham DE, Miller C. A thermodynamic framework for understanding temperature sensing by transient receptor potential (TRP) channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:19492–19497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117485108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero-Morales JF, Gracheva EO, Julius D. Cytoplasmic ankyrin repeats of transient receptor potential A1 (TRPA1) dictate sensitivity to thermal and chemical stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E1184–1191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114124108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCaen PG, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Sharp EM, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Sequential formation of ion pairs during activation of a sodium channel voltage sensor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:22498–22503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912307106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara Y, Kurokawa T, Takeshita K, Kobayashi M, Okochi Y, Nakagawa A, Okamura Y. The cytoplasmic coiled-coil mediates cooperative gating temperature sensitivity in the voltage-gated H(+) channel Hv1. Nature communications. 2012;3:816. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandl J, Hu H, Bandell M, Bursulaya B, Schmidt M, Petrus M, Patapoutian A. Pore region of TRPV3 ion channel is specifically required for heat activation. Nature neuroscience. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nn.2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. 3. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Howard RJ, Clark KA, Holton JM, Minor DL., Jr Structural insight into KCNQ (Kv7) channel assembly and channelopathy. Neuron. 2007;53:663–675. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie K, Kitagawa K, Nagura H, Imai T, Shimomura T, Fujiyoshi Y. Comparative study of the gating motif and C-type inactivation in prokaryotic voltage-gated sodium channels. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3685–3694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.057455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie K, Shimomura T, Fujiyoshi Y. The C-terminal helical bundle of the tetrameric prokaryotic sodium channel accelerates the inactivation rate. Nature communications. 2012;3:793. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabba S, Goyal R, Sosa-Pagan JO, Moldenhauer H, Wu J, Kalmeta B, Bandell M, Latorre R, Patapoutian A, Grandl J. Directionality of temperature activation in mouse TRPA1 ion channel can be inverted by single-point mutations in ankyrin repeat six. Neuron. 2014;82:1017–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke G. Distance measurements in the nanometer range by pulse EPR. Chemphyschem : a European journal of chemical physics and physical chemistry. 2002;3:927–932. doi: 10.1002/1439-7641(20021115)3:11<927::AID-CPHC927>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Lee A, Chen J, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. Crystal structure and mechanism of a calcium-gated potassium channel. Nature. 2002;417:515–522. doi: 10.1038/417515a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koishi R, Xu H, Ren D, Navarro B, Spiller BW, Shi Q, Clapham DE. A superfamily of voltage-gated sodium channels in bacteria. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9532–9538. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313100200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lolicato M, Riegelhaupt PM, Arrigoni C, Clark KA, Minor DL., Jr Transmembrane helix straightening and buckling underlies activation of mechanosensitive and thermosensitive K(2P) channels. Neuron. 2014;84:1198–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Klem AM, Ramu Y. Coupling between voltage sensors and activation gate in voltage-gated K+ channels. J Gen Physiol. 2002;120:663–676. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas AN, Gruber M. The structure of alpha-helical coiled coils. Adv Protein Chem. 2005;70:37–78. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)70003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maingret F, Lauritzen I, Patel AJ, Heurteaux C, Reyes R, Lesage F, Lazdunski M, Honore E. TREK-1 is a heat-activated background K(+) channel. Embo J. 2000;19:2483–2491. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCusker EC, Bagneris C, Naylor CE, Cole AR, D'Avanzo N, Nichols CG, Wallace BA. Structure of a bacterial voltage-gated sodium channel pore reveals mechanisms of opening and closing. Nature communications. 2012;3:1102. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHaourab HS, Steed PR, Kazmier K. Toward the fourth dimension of membrane protein structure: insight into dynamics from spin-labeling EPR spectroscopy. Structure. 2011;19:1549–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mio K, Mio M, Arisaka F, Sato M, Sato C. The C-terminal coiled-coil of the bacterial voltage-gated sodium channel NaChBac is not essential for tetramer formation, but stabilizes subunit-to-subunit interactions. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2010;103:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miroux B, Walker JE. Over-production of proteins in Escherichia coli: mutant hosts that allow synthesis of some membrane proteins and globular proteins at high levels. J Mol Biol. 1996;260:289–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morais-Cabral JH, Robertson GA. The enigmatic cytoplasmic regions of KCNH channels. J Mol Biol. 2015;427:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen CE, Armache JP, Gao Y, Cheng Y, Julius D. Structure of the TRPA1 ion channel suggests regulatory mechanisms. Nature. 2015;520:511–517. doi: 10.1038/nature14367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov E, Bladen C, Winkfein R, Diao C, Dhaliwal P, French RJ. The pore, not cytoplasmic domains, underlies inactivation in a prokaryotic sodium channel. Biophys J. 2005;89:232–242. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.056994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payandeh J, Gamal El-Din TM, Scheuer T, Zheng N, Catterall WA. Crystal structure of a voltage-gated sodium channel in two potentially inactivated states. Nature. 2012;486:135–139. doi: 10.1038/nature11077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payandeh J, Minor DL., Jr Bacterial Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels (BacNas) from the Soil, Sea, and Salt Lakes Enlighten Molecular Mechanisms of Electrical Signaling and Pharmacology in the Brain and Heart. J Mol Biol. 2015;427:3–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payandeh J, Scheuer T, Zheng N, Catterall WA. The crystal structure of a voltage-gated sodium channel. Nature. 2011;475:353–358. doi: 10.1038/nature10238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pioletti M, Findeisen F, Hura GL, Minor DL., Jr Three-dimensional structure of the KChIP1-Kv4.3 T1 complex reveals a cross-shaped octamer. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:987–995. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powl AM, O'Reilly AO, Miles AJ, Wallace BA. Synchrotron radiation circular dichroism spectroscopy-defined structure of the C-terminal domain of NaChBac and its role in channel assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14064–14069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001793107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren D, Navarro B, Xu H, Yue L, Shi Q, Clapham DE. A prokaryotic voltage-gated sodium channel. Science. 2001;294:2372–2375. doi: 10.1126/science.1065635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuer T. Bacterial sodium channels: models for eukaryotic sodium and calcium channels. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. 2014;221:269–291. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-41588-3_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider ER, Anderson EO, Gracheva EO, Bagriantsev SN. Temperature sensitivity of two-pore (K2P) potassium channels. Current topics in membranes. 2014;74:113–133. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800181-3.00005-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaya D, Findeisen F, Abderemane-Ali F, Arrigoni C, Wong S, Nurva SR, Loussouarn G, Minor DL., Jr Structure of a prokaryotic sodium channel pore reveals essential gating elements and an outer ion binding site common to eukaryotic channels. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:467–483. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaya D, Kreir M, Robbins RA, Wong S, Hammon J, Bruggemann A, Minor DL., Jr Voltage-gated sodium channel (NaV) protein dissection creates a set of functional pore-only proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:12313–12318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106811108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshita K, Sakata S, Yamashita E, Fujiwara Y, Kawanabe A, Kurokawa T, Okochi Y, Matsuda M, Narita H, Okamura Y, et al. X-ray crystal structure of voltage-gated proton channel. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2014;21:352–U170. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L, Gamal El-Din TM, Payandeh J, Martinez GQ, Heard TM, Scheuer T, Zheng N, Catterall WA. Structural basis for Ca2+ selectivity of a voltage-gated calcium channel. Nature. 2014;505:56–61. doi: 10.1038/nature12775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai CJ, Tani K, Irie K, Hiroaki Y, Shimomura T, McMillan DG, Cook GM, Schertler GF, Fujiyoshi Y, Li XD. Two alternative conformations of a voltage-gated sodium channel. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:4074–4088. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmschneider MB, Bagneris C, McCusker EC, Decaen PG, Delling M, Clapham DE, Ulmschneider JP, Wallace BA. Molecular dynamics of ion transport through the open conformation of a bacterial voltage-gated sodium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:6364–6369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214667110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uysal S, Vasquez V, Tereshko V, Esaki K, Fellouse FA, Sidhu SS, Koide S, Perozo E, Kossiakoff A. Crystal structure of full-length KcsA in its closed conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6644–6649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810663106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas E, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Khalili-Araghi F, Catterall WA, Klein ML, Tarek M, Lindahl E, Schulten K, Perozo E, Bezanilla F, et al. An emerging consensus on voltage-dependent gating from computational modeling and molecular dynamics simulations. J Gen Physiol. 2012;140:587–594. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vriens J, Nilius B, Voets T. Peripheral thermosensation in mammals. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2014;15:573–589. doi: 10.1038/nrn3784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener R, Haitin Y, Shamgar L, Fernandez-Alonso MC, Martos A, Chomsky-Hecht O, Rivas G, Attali B, Hirsch JA. The KCNQ1 (Kv7.1) COOH terminus, a multitiered scaffold for subunit assembly and protein interaction. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:5815–5830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707541200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Zhang G, Cui J. BK channels: multiple sensors, one activation gate. Frontiers in physiology. 2015;6:29. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yifrach O, MacKinnon R. Energetics of pore opening in a voltage-gated K(+) channel. Cell. 2002;111:231–239. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu FH, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Gutman GA, Catterall WA. Overview of molecular relationships in the voltage-gated ion channel superfamily. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:387–395. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Ulbrich MH, Li MH, Dobbins S, Zhang WK, Tong L, Isacoff EY, Yang J. Molecular mechanism of the assembly of an acid-sensing receptor ion channel complex. Nature communications. 2012;3:1252. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan P, Leonetti MD, Pico AR, Hsiung Y, MacKinnon R. Structure of the human BK channel Ca2+-activation apparatus at 3.0 A resolution. Science. 2010;329:182–186. doi: 10.1126/science.1190414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagotta WN, Olivier NB, Black KD, Young EC, Olson R, Gouaux E. Structural basis for modulation and agonist specificity of HCN pacemaker channels. Nature. 2003;425:200–205. doi: 10.1038/nature01922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Ren W, DeCaen P, Yan C, Tao X, Tang L, Wang J, Hasegawa K, Kumasaka T, He J, et al. Crystal structure of an orthologue of the NaChBac voltage-gated sodium channel. Nature. 2012;486:130–134. doi: 10.1038/nature11054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.