Abstract

Objective

Foodborne illnesses in Australia, including salmonellosis, are estimated to cost over $A1.25 billion annually. The weather has been identified as being influential on salmonellosis incidence, as cases increase during summer, however time series modelling of salmonellosis is challenging because outbreaks cause strong autocorrelation. This study assesses whether switching models is an improved method of estimating weather–salmonellosis associations.

Design

We analysed weather and salmonellosis in South-East Queensland between 2004 and 2013 using 2 common regression models and a switching model, each with 21-day lags for temperature and precipitation.

Results

The switching model best fit the data, as judged by its substantial improvement in deviance information criterion over the regression models, less autocorrelated residuals and control of seasonality. The switching model estimated a 5°C increase in mean temperature and 10 mm precipitation were associated with increases in salmonellosis cases of 45.4% (95% CrI 40.4%, 50.5%) and 24.1% (95% CrI 17.0%, 31.6%), respectively.

Conclusions

Switching models improve on traditional time series models in quantifying weather–salmonellosis associations. A better understanding of how temperature and precipitation influence salmonellosis may identify where interventions can be made to lower the health and economic costs of salmonellosis.

Keywords: salmonellosis, disease outbreaks, temperature, rainfall, Australia

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Strong associations were identified between higher temperatures, increased precipitation and salmonellosis, which is a valuable information for developing prevention strategies.

Switching models can overcome common issues with traditional time series models of weather–disease associations, such as managing outbreaks.

Daily salmonellosis notifications and weather were slightly misaligned, potentially reducing the estimates of weather–salmonellosis associations.

Disease notification data under-reports disease incidence, and may obscure important social and environmental patterns, or introduce artificial patterns in salmonellosis incidence.

Salmonellosis is a major foodborne illness globally, incurring substantial health and economic costs. Salmonellosis is a bacterial infection typically acquired through consumption of contaminated poultry meat and eggs, although cases have been linked to raw milk and fresh produce including melons and sprouts.1–3 Gastrointestinal symptoms present within 6–72 h of infection, and persist for an average of 3–7 days. While symptoms typically resolve spontaneously, salmonellosis can have severe health outcomes including chronic arthritis and postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Salmonellosis caused eight deaths and contributed to a further 24 deaths in Australia in 2013.4

There are approximately 12 900 notified salmonellosis cases in Australia annually. Cases are greatly under-reported in surveillance data as medical attention is not often sought for the common, self-limiting symptoms. Incidence is reportedly seven times the number of notified cases,5 putting the likely number of salmonellosis cases in Australia at approximately 90 300 annually. Foodborne gastroenteritis, including salmonellosis, is estimated to cost over $A1.25 billion annually in healthcare, absenteeism and monitoring and controlling outbreaks.6 Reducing salmonellosis incidence would substantially reduce the health and economic costs of foodborne disease in Australia.

Weather is a key influence on salmonellosis. Higher temperatures enable quicker replication of Salmonella, increasing the contamination risk throughout the paddock-to-plate chain. Two potential risks arise through colonisation of broiler flocks on warm days and food-handling mistakes during meal preparation, such as leaving meat at room temperature. Precipitation also increases salmonellosis risk as run-off over land increases pathogen loads in water sources. Individuals may then contract salmonellosis through recreational contact with contaminated water, or drinking rainwater from household tanks, and outbreaks have been linked to the use of contaminated water in producing papaya and cantaloupe.1 7–9

The influence of weather on salmonellosis is not always immediate but most often delayed after a weather event. Studies have found delays of 2–4 weeks between a hot day or high precipitation, and a corresponding increase in salmonellosis cases.10 11 These delays reflect how, for example, a hot day may facilitate colonisation of Salmonella in a broiler flock, however, the consequent human salmonellosis cases will not occur until those chickens are consumed days or weeks later.

Seasonal fluctuations in salmonellosis cases also result from indirect effects of season. For example, patterns of food consumption change seasonally as leafy green vegetables, an increasingly common source of salmonellosis, are eaten in larger quantities in warmer months.12 Food safety campaigns are also run throughout summer which raises awareness of symptoms and subsequent rates of seeking medical attention, generating an artificial peak in summer case numbers. These examples demonstrate how seasonal factors can introduce both genuine and artificial fluctuations in disease notifications.

The common practice in time series studies of foodborne illness to statistically control seasonality, aims to reduce the effect of artificial influences, however, also serves to eliminate the genuine influences. Analyses have resorted to using the immediate past to predict the future by including autoregressive or moving average terms.10 13 Others included splines or random effects to remove unexplained variance, or fit omnibus terms for season, but did not explain what season is.11 14 15 These models may produce well-behaved residuals, but such techniques may obscure the effects of temperature and precipitation on salmonellosis and hinder our understanding of the aetiological processes through which weather affects salmonellosis. Consequently, we need specialised methods to filter out extraneous seasonal factors while retaining the causal effects of temperature and precipitation on salmonellosis.

Markov switching models may be one method of obtaining better estimates of the independent effects of weather variables by focusing on outbreaks. Salmonellosis may be contracted sporadically by an individual consuming contaminated food, or in an outbreak where multiple people are infected in temporal proximity due to a common food source. Sporadic cases are of more interest than outbreak cases in examining the effect of weather, as weather may instigate an outbreak, for example, a restaurant not refrigerating its eggs is riskier in summer when room temperatures are higher, but the high case numbers result from the common point of contamination rather than from temperature directly. Previous studies have attempted to reduce the effect of outbreak cases by removing known outbreak cases or by truncating case numbers at an upper limit,10 16 however, these methods are not infallible, as outbreak cases cannot always be identified, and the upper limits used are often arbitrary.

Switching models simultaneously fit two models to a time series, and alternate between modelling sporadic and outbreak cases.17 Outbreak cases are modelled using an AR-1 autoregressive term, reflecting the nature of outbreaks as inter-related, while sporadic cases are modelled using temperature and precipitation predictors. In modelling outbreak and sporadic cases separately, the extraneous influence of outbreak cases can be removed from estimates of the association between weather and sporadic cases which eliminates the need to make further adjustments for season and provides estimates of the independent effects of temperature and precipitation.

This study serves to assess the capability of switching models to improve on traditional approaches to time series studies of weather and foodborne disease by comparing two traditional lagged regression models to a lagged switching model. We hypothesise that temperature and precipitation will increase salmonellosis cases in all three models, and that the switching model will provide more accurate weather–disease associations by removing the influence of outbreaks.

Methods

Study region

We analysed South-East Queensland (SEQ), a region with strong seasonal patterns of salmonellosis with incidence peaking in summer. SEQ has a subtropical climate with mild winters and hot, humid summers (December–February) when most precipitation occurs. On average, 1480 notified cases of salmonellosis occur in SEQ annually, approximately 10 360 cases annually after adjusting for under-reporting.5 SEQ includes the state capital Brisbane and has 3.2 million residents.

Weather data

The Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) compiles high-quality weather data for thousands of Australian sites. We obtained recordings of daily minimum and maximum temperatures, and precipitation from BOM weather stations in SEQ for 1 January 2004 to 31 December 2013. A station’s data were included if there were no missing data for precipitation, or <6% missing data for temperature. These thresholds optimally balanced the geographic spread of stations with tolerable levels of missing data. Fifteen temperature and 60 precipitation stations had suitable data (see online supplementary technical appendix, figure A1). Missing temperature data were imputed using the RClimTool (Colombian Climate and Agriculture, Colombia). We calculated regional daily precipitation, and minimum, mean and maximum temperatures by averaging recordings across all stations (see online supplementary technical appendix, table A1, figures A2 and A3).

bmjopen-2015-010204supp.pdf (481KB, pdf)

Notifications data

Notified cases under-represent salmonellosis incidence as attrition occurs throughout the notification process if an ill person does not see a doctor, a stool sample is not viable, or a sample returns a false negative for a pathogen. Salmonellosis is a legally notifiable disease in Queensland, so although under-reporting occurs, confirmed cases are reliably reported.5 Under-reporting is believed to be stable across 2004–2013, and so should not influence estimates of weather–salmonellosis associations (R Stafford, personal communication, 30 April 2015). In August 2013, Queensland Health introduced a more sensitive test for salmonellosis which likely increased the number of notifications recorded (R Stafford, personal communication), and we adjusted for this step change in our models (see below).

The daily number of notified salmonellosis cases in SEQ from 1 January 2004 to 31 December 2013 was supplied by Queensland Health. The case date is the date a patient’s stool sample was collected, which is the closest date to symptom onset available. The date of symptom onset would allow a more precise alignment of daily weather and cases, however, the high number of cases makes it infeasible to interview each patient to determine when their symptoms began. For the same reason, cases could not be identified as outbreak related or sporadic, nor whether the case was acquired locally or outside of Queensland or Australia.

Statistical analyses

We examined descriptive statistics for all variables, and calculated correlation coefficients between temperature, precipitation and salmonellosis cases. We fitted three models: a standard regression, an autoregressive regression, and a switching model, all with smoothed lags for temperature and precipitation. We calculated the per cent change in salmonellosis risk per 5°C increase in temperature and 10 mm increase in daily precipitation, together with Bayesian 95% credible intervals.

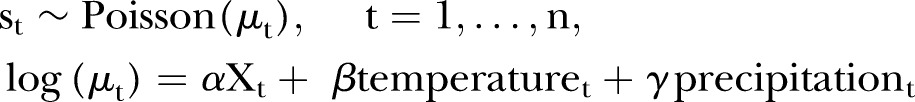

Standard regression model

We fitted a Poisson regression model for daily salmonellosis cases with distributed lags of 21 days for daily mean temperature and precipitation using natural splines with 3 degrees of freedom as predictors. Using a spline for temperature and precipitation reduced the collinearity between the lag terms, improving the accuracy of the model.18 We decided a priori to examine a lag of 21 days because this represented a biologically plausible time frame in which Salmonella could be transmitted to humans from an animal or the environment. In all models, we included quadratic and linear terms for time to control for the upward trend in salmonellosis incidence over time due to population growth and non-weather-related factors. We identified effects of day of the week and public holidays, which we modelled using categorical variables, and a binary variable for days after 1 August 2013, to control for the change in pathology tests. The regression model was:

|

where st is the number of cases on day t and X a design matrix that fits the intercept, day of the week, public holiday, trend and change in pathology test. We tried minimum, mean and maximum temperatures, however, the results were similar, so we used mean temperature, as this gave the best fit.

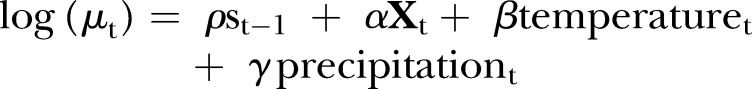

Autoregressive regression model

Autocorrelation between daily counts of salmonellosis cases was observed. Ignoring this autocorrelation would incorrectly assume that observations are independent and potentially underestimate the model's SEs.19 As such, the first model is likely to be naïve, however, it provides useful information about the change in parameter estimates and residuals when an autoregressive term is added. We used an AR-1 term as this lag showed the strongest autocorrelation. This model was the same as the standard regression model with the inclusion of the autoregressive term:

|

The autoregressive term uses yesterday's case numbers, so when yesterday's case numbers are high the expected number of cases today is also high (assuming ρ>0). We experimented with using the log number of yesterday's cases, and using the identity link in place of the log link, but neither gave as good a fit to the data as the above model.

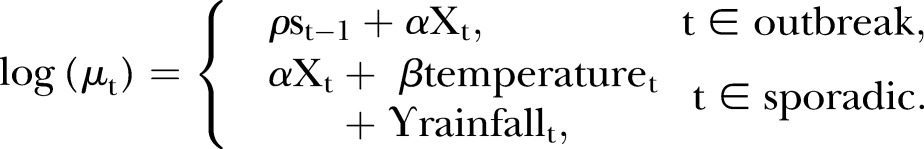

Switching model

Switching models alternate between two methods of modelling cases based on whether cases are outbreak or sporadic. During outbreak phases when there are a high number of related cases, the switching model includes an AR-1 autoregressive term to predict the daily number of cases. During sporadic phases, the daily cases are modelled using the weather variables (and other predictor variables described for the standard regression model) with no autoregressive term. The phase is determined through shifts in the daily case numbers, with large changes incurring a phase change.17 The two regression equations are:

|

The model switches between the sporadic and outbreak phases using a Markov process with two states: outbreak and sporadic. The probability of switching at time t depends on the state at time t−1. The switching probabilities and states are unknown parameters which are estimated together with the regression parameters.

All three models were fitted using a Bayesian paradigm, and results are presented as the per cent change in cases and 95% credible intervals. Estimates were made using two Markov chain Monte Carlo with 3000 iterations, using R V.3.1.1 and JAGS V.3.4.0 (R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2014; Plummer M. rjags: Bayesian graphical models using MCMC. 2015. R package version 3–15. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rjags). We visually examined the coalescence of the two chains to check for convergence. To assess performance and compare models, we calculated each model's deviance information criterion (DIC), and examined the residuals using an autocorrelation function (ACF) and cumulative periodogram plots (see online supplementary technical appendix, figures A4 and A5). We also conducted sensitivity analyses on the switching models to assess the effect of precipitation and temperature separately (see online supplementary technical appendix, table A2 and figure A6). R and JAGS code for two models is available in the online supplementary technical appendix (Part 2).

Results

There were 14 800 salmonellosis cases notified in SEQ during 2004–2013. More cases occurred in summer than in winter, and cases were positively correlated with daily mean temperature (0.4) and precipitation (0.04).

The standard regression model estimated that a 5°C increase in mean temperature was associated with a 59.4% increase in salmonellosis cases (95% CrI 55.1%, 63.7%), while a 10 mm increase in precipitation increased cases by 14.6% (95% CrI 9.2%, 20.3%). After adding an autoregressive term to the standard model, a 5°C increase in mean temperature was associated with a 50.6% increase in cases (95% CrI 46.3%, 55.1%), and 10 mm of precipitation increased cases by 11.4% (95% CrI (6.3%, 16.8%). As expected, consecutive days’ cases were positively correlated (r=0.41). The switching model estimated a 45.4% increase in cases (95% CrI 40.4%, 50.5%) after a 5°C increase in mean temperature and 24.1% increase (95% CrI 17.0%, 31.6%) following 10 mm of precipitation (figure 1). The switching model estimated 77% of days (2831) as sporadic cases, meaning the predictor variables were used to model most days, with the remaining 23% of days modelled as outbreaks using the autoregressive term. Parameter estimates are available in online supplementary table A3 in the technical appendix.

Figure 1.

Estimates of the per cent change in cases per 5°C increase in temperature and 10 mm increase in precipitation for each model.

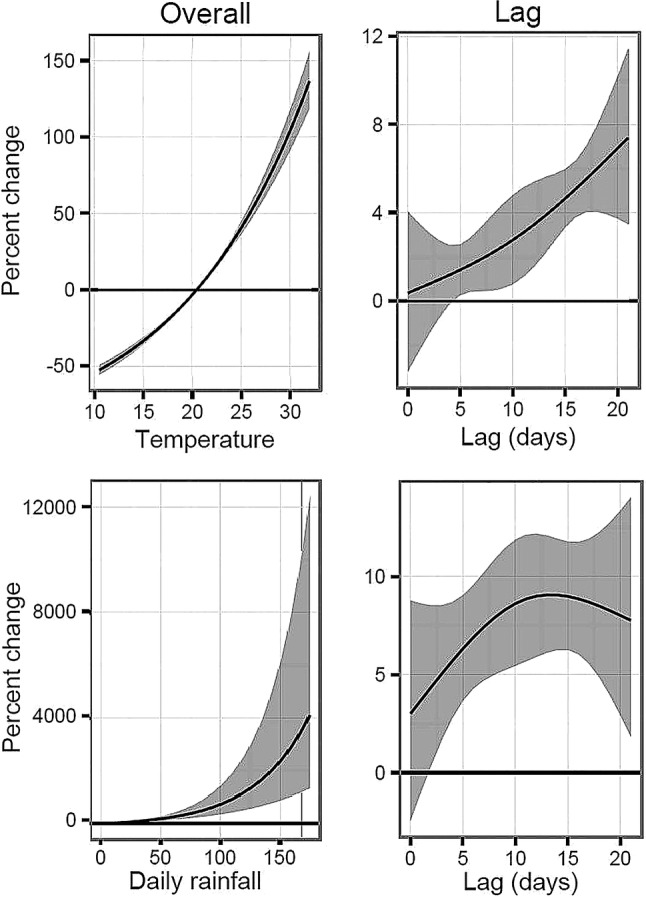

All three models exhibited similar risk patterns for the overall effects of temperature and precipitation and over the lag period (figure 2). Higher temperatures steadily increased the risk of salmonellosis, and the risk steadily increased in the 5–21 days following a high temperature. Salmonellosis risk also increased with greater precipitation, with the risk increasing from 2 to 12 days after a heavy rainfall event, then decreasing slightly over the remaining days.

Figure 2.

Overall per cent change in cases by daily mean temperature and by days of lag following a day with a mean temperature of 30°C, and per 1 mm change in daily precipitation and by days of lag after a day with 75 mm precipitation.

We examined each model's ACFs, cumulative periodogram and DIC to assess which model achieved the best fit. The residuals of the switching model showed substantially less autocorrelation than those from the regression models, indicating that the outbreak phase of the model managed the autocorrelation between cases. As expected, the autoregressive model had less autocorrelated residuals than the standard regression, but still more than the switching model. We plotted each model's residuals annually and found the years 2007 and 2009 were consistently the least well fit across all models. We observed no anomalous behaviour in notifications data and no changes to the notification system in these years. However, both years broke Queensland temperature records with maximum temperatures in autumn 2007 and winter 2009 2.0°C and 4.3°C above average, respectively.20 21 Precipitation was also greatly above average in autumn 2009, then the lowest recorded in winter 2009.21 These unusual weather events may have influenced salmonellosis cases, resulting in a poorer fit of the models for these years.

The cumulative periodograms showed that residual seasonal patterns were unaccounted for by both regression models, however, no seasonal patterns remained evident for the switching model showing that seasonality has effectively been controlled for by removing the influence of outbreaks. The switching model also recorded the lowest DIC at 313 and 90 points lower than the standard and autoregressive regression models, respectively. As 10 points is considered a substantial improvement, these statistics affirm that the switching model had the best fit. ACF plots and cumulative periodograms are in the online supplementary technical appendix figures A4 and A5.

We further validated the switching model by comparing its outbreak phases with the outbreaks reported by government surveillance to test its ability to detect known outbreaks (see online supplementary technical appendix, figure A7 and table A4). The model detected most of the government-reported outbreaks, although the model's outbreaks often persisted longer than those reported by the government, as the government requires environmental or epidemiological evidence to link a case to an outbreak. The model has no such requirements, and so may associate earlier and more cases with an outbreak, reporting longer outbreak durations. However, the substantial alignment between outbreaks reported by the model and the government demonstrates the ability of the switching model to control for outbreaks.

Discussion

Summary and comparison with previous estimates

This study found that higher daily mean temperature and precipitation increase the risk of contracting salmonellosis. Previous studies using autoregressive models estimated that salmonellosis cases in Brisbane rose by 5.8% per 1°C increase in minimum temperature 2 weeks previously,10 or 62% per 5°C rise in the previous month’s mean temperature.11 The current study's regression models made comparable estimates of 59.4% and 50.6% increases in cases per 5°C increase in mean daily temperature. Another study using an autoregressive model found salmonellosis cases in Brisbane increased by 0.2% 2 weeks after a heavy precipitation event.10 All three models estimated positive associations between precipitation and salmonellosis, however, the strength of the association was much higher, with cases estimated to increase by between 11.4% and 24.1% per 10 mm precipitation. This discrepancy could be due to different study periods and geographic regions examined between studies.

Previous studies may have inaccurately estimated weather–salmonellosis associations through the use of autoregressive and seasonality terms, as such terms are likely to explain variance in case numbers that would be due to temperature and precipitation. Switching models use autoregressive terms more sparingly, allowing weather to explain more of the variation in cases, and producing higher, and likely more accurate, estimates of weather–salmonellosis associations.

Contamination of broiler flocks is one possible mechanism through which higher temperatures increase salmonellosis cases. Heat stress can induce enteritis in chickens with Salmonella present in their guts, and the bacteria are more likely to spread to other organs.22 During processing, spills of visceral material containing Salmonella may contaminate the meat. In Queensland, approximately 44% of chicken carcases postslaughter are contaminated with Salmonella, and viscerally contaminated meat was linked to a 196% increase in salmonellosis cases in northern Queensland during 2011.23 24 The results of our study support this transmission pathway as the delayed increase in salmonellosis cases may occur due to lags between colonisation of flocks on warm days and case onset following processing and human consumption. The more acute effects of high temperatures on salmonellosis incidence are likely due to food handling mistakes closer to the time of consumption, combined with delays in symptom onset and seeking medical attention.

Precipitation likely increases salmonellosis incidence shortly after a rainfall event by increasing pathogen loads in household rainwater tanks through run-off from gutters or in surface waters which individuals may have recreational contact with.7 8 The delayed effect of rainfall on salmonellosis is also likely to be through increased pathogen loads in surface water which is then used to irrigate or process fresh produce later consumed raw, as was the suspected source of an Australian outbreak linked to papaya.1 9 Produce grown in open fields may also be directly contaminated, as precipitation splashes water and soil containing pathogens onto produce which is later eaten raw.25 These results support previous findings that temperature and precipitation exert a strong influence on salmonellosis incidence in Queensland.

Assessment of switching models as an improved method

This study demonstrates that switching models improve on traditional techniques of modelling salmonellosis. The switching model achieved a substantially lower DIC than the regression models, had less autocorrelated residuals, and showed no confounding residual seasonal patterns. We also validated the model by showing that it accurately predicted most outbreaks reported by government surveillance.

The switching model's better fit likely stems from its improved control of outbreaks. Traditional techniques of modelling weather–salmonellosis often manage outbreaks through imperfect means such as truncating case numbers or discarding outbreak cases.10 16 Similarly, multiple temperature splines or moving average terms are often included to control for unexplained seasonal patterns,10 11 which produces well-behaved residuals, but does not explain what aspect of season influences salmonellosis. Our switching model required no such techniques to control for seasonality and inherently managed outbreaks by modelling them separately to sporadic cases. The results of this study indicate that adequately controlling outbreaks, as the switching model does but regression models do not, accounts for extraneous seasonal patterns, and produces a better fit.

The switching model's results are, therefore, likely more accurate estimates of weather–salmonellosis associations. The smaller temperature effect and larger precipitation effect in the switching model (figure 1) suggests that ineffectively removing the influence of outbreaks overestimates the effect of temperature and underestimates the effect of precipitation on salmonellosis.

Limitations and future directions

Reliance on notification data is a common limitation of weather–disease studies. Notification data under-report cases,5 and severe cases are likely over-represented. Although under-reporting is believed to be consistent across the study period and unlikely to influence the weather–disease relationship, under-reporting may obscure important social or environmental patterns, or generate artificial patterns in salmonellosis incidence. For example, negative associations were observed between weekends and salmonellosis, however, this likely occurs as individuals are less likely to see a doctor and have their case notified on a weekend. Another limitation is the slight misalignment between infection and weather due to each case’s date being the date a stool sample was taken, not the date of symptom onset. This potentially reduces the estimates of weather–salmonellosis associations. Further, this study obtained regional weather data by averaging recordings from several stations which could also reduce estimates of associations by dampening weather extremes and misaligning the location of cases with weather. However, it is worth noting that our estimates were strongly statistically significant, and larger than previous estimates in the literature.

Models which achieve good statistical fit enable accurate prediction of case numbers, as such lagged switching models could be used in surveillance of foodborne diseases. Indeed, switching models are currently applied in influenza surveillance in Spain.17 However, while predicting infectious disease cases is useful in allocating resources to manage outbreaks, understanding the causes of foodborne diseases can direct resources towards prevention. This study provides evidence for general pathways through which weather influences salmonellosis, future studies may then identify potential interventions to these pathways to aid prevention.

Conclusions

Understanding the aetiology of weather–salmonellosis associations is integral to implementing preventative strategies to reduce the impact of salmonellosis. This study identifies switching models as a means of achieving a better understanding of these relationships, and likely provides more accurate estimates of the effects of temperature and precipitation on salmonellosis. These findings are directly applicable in preventative strategies to reduce the cost of salmonellosis in Australia.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Russell Stafford of Queensland Health for his valuable advice regarding foodborne disease notifications, and the Australian Bureau of Meteorology and the Communicable Disease Branch of Queensland Health for providing data.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Adrian Barnett at @aidybarnett

Contributors: AGB conceived the study and together with DMS developed the switching models. DMS undertook data preparation and analysis and AGB provided statistical guidance. The manuscript was written by DMS and edited by AGB. Both authors had full access to all the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Queensland University of Technology Humans Research Ethics Committee (approval number 1400000850).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Munnoch SA, Ward K, Sheridan S et al. A multi-state outbreak of Salmonella Saintpaul in Australia associated with cantaloupe consumption. Epidemiol Infect 2009;137:367–74. 10.1017/S0950268808000861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.OzFoodNet Working Group. Burden and causes of foodborne disease in Australia: annual report of the OzFoodNet network, 2005. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep 2006;30:278–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Percival SL, Williams DW. Salmonella. In: Percival SL, Yates MV, Williams DW et al., eds Microbiology of waterborne diseases: microbiological aspects and risks. 2nd edn London: Elsevier, 2014:209–22. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Causes of Death, Australia, 2013 (cat. no. 3303.0). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall G, Yohannes K, Raupach J et al. Estimating community incidence of Salmonella, Campylobacter, and Shiga Toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections, Australia. Emerg Infect Dis 2008;14:1601–9. 10.3201/eid1410.071042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abelson P, Potter Forbes M, Hall G. The annual cost of foodborne illness in Australia. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sidhu JPS, Ahmed W, Gernjak W et al. Sewage pollution in urban stormwater runoff as evident from the widespread presence of multiple microbial and chemical source tracking markers. Sci Total Environ 2013;463–464:488–96. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed W, Vieritz A, Goonetilleke A et al. Health risk from the use of roof-harvested rainwater in southeast Queensland, Australia, as potable or nonpotable water, determined using quantitative microbial risk assessment. Appl Environ Microbiol 2010;76:7382–91. 10.1128/AEM.00944-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibbs R, Pingault N, Mazzucchelli T et al. An outbreak of Salmonella enterica serotype Litchfield infection in Australia linked to consumption of contaminated papaya. J Food Protect 2009;72:1094–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Bi P, Hiller JE. Climate variations and Salmonella infection in Australian subtropical and tropical regions. Sci Total Environ 2010;408:524–30. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.10.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Souza RM, Becker NG, Hall G et al. Does ambient temperature affect food-borne disease? Epidemiology 2004;15:86–92. 10.1097/01.ede.0000101021.03453.3e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu C, Hofstra N, Franz E. Impacts of climate change on the microbial safety of pre-harvest leafy green vegetables as indicated by Escherichia coli O157 and Salmonella spp. Int J Food Microbiol 2013;163:119–28. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bi P, Cameron AS, Zhang Y et al. Weather and notified Campylobacter infections in temperate and sub-tropical regions of Australia: an ecological study. J Infect 2008;57:317–23. 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovats RS, Edwards SJ, Hajat S et al. The effect of temperature on food poisoning: a time-series analysis of salmonellosis in ten European countries. Epidemiol Infect 2004;132:443–53. 10.1017/S0950268804001992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lal A, Ikeda T, French N et al. Climate variability, weather and enteric disease incidence in New Zealand: time series analysis. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e83484 10.1371/journal.pone.0083484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Bi P, Hiller JE. Climate variations and salmonellosis transmission in Adelaide, South Australia: a comparison between regression models. Int J Biometeorol 2008;52:179–87. 10.1007/s00484-007-0109-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martínez-Beneito MA, Conesa D, López-Quílez A et al. Bayesian Markov Switching models for the early detection of influenza epidemics. Stat Med 2008;27:4455–68. 10.1002/sim.3320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhaskaran K, Gasparrini A, Hajat S et al. Time series regression studies in environmental epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:1187–95. 10.1093/ije/dyt092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoeting JA. The importance of accounting for spatial and temporal correlation in analyses of ecological data. Ecol Appl 2009;19:574–7. 10.1890/08-0836.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Climate Centre. Warmest May and autumn on record in eastern Australia. Canberra: Bureau of Meteorology, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Climate Centre. Exceptional winter heat over large parts of Australia. Canberra: Bureau of Meteorology, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palermo-Neta J, Calefi AS, Aloia TP et al. Heat stress impairs performance parameters, immunity and increases Salmonella enteritidis migration to spleen of broilers chickens. Brain Behav Immunity 2013;32:e18 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.07.075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Food Standards Australia and New Zealand and South Australian Research and Development Institute. Baseline survey on the prevalence and concentration of Salmonella and Campylobacter in chicken meat on-farm and at primary processing. Canberra: Food Standards Australia and New Zealand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.OzFoodNet. OzFoodNet—enhancing foodborne disease surveillance across Australia—3rd quarter summary, 2011. Brisbane, Queensland: Queensland Health, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weller D, Wiedmann M, Strawn L. Spatial and temporal factors associated with an increased prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes in New York State spinach fields. Appl Environ Microbiol 2015; 81:6059–69. 10.1128/AEM.01286-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010204supp.pdf (481KB, pdf)