Abstract

Objectives

Pharmacists play a role in providing medication reconciliation. However, data on effectiveness on patients’ clinical outcomes appear inconclusive. Thus, the aim of this study was to systematically investigate the effect of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programmes on clinical outcomes at hospital transitions.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

We searched PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, IPA, CINHAL and PsycINFO from inception to December 2014. Included studies were all published studies in English that compared the effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation interventions to usual care, aimed at improving medication reconciliation programmes. Meta-analysis was carried out using a random effects model, and subgroup analysis was conducted to determine the sources of heterogeneity.

Results

17 studies involving 21 342 adult patients were included. Eight studies were randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Most studies targeted multiple transitions and compared comprehensive medication reconciliation programmes including telephone follow-up/home visit, patient counselling or both, during the first 30 days of follow-up. The pooled relative risks showed a more substantial reduction of 67%, 28% and 19% in adverse drug event-related hospital revisits (RR 0.33; 95% CI 0.20 to 0.53), emergency department (ED) visits (RR 0.72; 95% CI 0.57 to 0.92) and hospital readmissions (RR 0.81; 95% CI 0.70 to 0.95) in the intervention group than in the usual care group, respectively. The pooled data on mortality (RR 1.05; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.16) and composite readmission and/or ED visit (RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.90 to 1.00) did not differ among the groups. There was significant heterogeneity in the results related to readmissions and ED visits, however. Subgroup analyses based on study design and outcome timing did not show statistically significant results.

Conclusion

Pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programmes are effective at improving post-hospital healthcare utilisation. This review supports the implementation of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programmes that include some component aimed at improving medication safety.

Keywords: Medication reconciliation, medication review, medication errors, medication discrepancies, pharmacists

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first systematic review investigating the effect of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programmes on clinical outcomes.

In some of the clinical outcomes evaluated, there is substantial statistical heterogeneity and we could not identify the source of variation among the studies.

The inclusion of non-controlled studies might affect the quality of evidence as seen by the high risk of bias in these groups of studies.

Introduction

Medication reconciliation has been recognised as a major intervention tackling the burden of medication discrepancies and subsequent patient harm at care transitions.1 Unjustifiable medication discrepancies are responsible for more than half of the medication errors occurring at transitions in care, when patients move in and out of hospital or get transferred to the care of other healthcare professionals,2 and up to one-third could have the potential to cause harm.3 Incidence of unintentional medication changes is common at care transitions,3–8 and is one of the reasons for a huge utilisation of healthcare resources.9–13 Medication reconciliation as a medication safety strategy has been championed by a number of healthcare organisations. It was first adopted in 2005 as a National Patient Safety Goal (NPSG) by the Joint Commission14 and, later, the WHO and collaborators15–17 involved themselves in endorsing this strategy across many countries.

Despite these efforts, implementation of a medication reconciliation service is a hospital-wide challenge,18 and there is no previous clinical evidence as to which member of the healthcare profession(s) or which strategies effectively perform medication reconciliation.19 A number of medication reconciliation strategies have been utilised for safe patient transitions: use of electronic reconciliation tools,20–22 standardised forms23 24 and collaborative models,25 26 as well as patient engagement27 and pharmacist-led approaches.28 29

The impact of medication reconciliation on clinical outcomes at hospital transitions has been reported, however, two recently published systematic reviews30 31 have ascertained that the benefit as a patient safety strategy is not clear. Both studies have inconsistent findings on healthcare resource utilisation. Unlike Mueller et al,30 Kwan et al31 did not report significant association between post-hospital healthcare utilisation and medication discrepancies identified through medication reconciliation interventions. Both reviews broadly assessed the effect of medication reconciliation produced by various strategies, including the use of collaborative models. The aim of the present review was, thus, to specifically assess the effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programmes on clinical outcomes during the transition to and from hospital settings.

Methods

Data sources and searches

The study was conducted utilising Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) group guidelines,32 including the PRISMA checklist, to ensure inclusion of relevant information. An initial limited search of articles was undertaken and the search strategy was broadened after analysis of the text words contained in the title, abstract and index terms. ‘Medication reconciliation’, ‘medication discrepancies’, ‘medication errors’, ‘medication history’ and ‘pharmac*’, were the main Medicine Subject Headings (MeSH) and text word terms in the electronic searches. Then, we carried out a comprehensive search involving all the collections in the databases until December 2014: PubMed/MEDLINE (1946), Ovid/MEDLINE (1946), International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (1970), EMBASE (1966), PsycINFO (1890) and CINHAL (1937) (see online supplementary appendix A). The reference lists of review articles and included studies were manually searched to locate articles that were not identified in the database search. Article search was performed by one reviewer (ABM) with the support of a medical librarian.

bmjopen-2015-010003supp_appendices.pdf (526.9KB, pdf)

Study selection

To be included in the selection, studies were required to present the following: papers that reported medication reconciliation intervention primarily and that provide data on any of these clinical end points (all-cause readmission, emergency department (ED) visits, composite rate of readmission and/or ED visits, mortality, adverse drug event (ADE)-related hospital visit). We adopted the definition of ‘medication reconciliation’ utilised by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement: ‘the process of identifying the most accurate list of a patient's current medicines including the name, dosage, frequency and route—and comparing them to the current list in use, recognising and documenting any discrepancies, thus resulting in a complete list of medications’.1 Included studies had to be original peer-reviewed research articles that were published in English. The included interventions had to start in the hospital and be performed primarily by a pharmacist, with the aim of improving care transitions to and from a hospital. The intervention had to have been compared with another group that received usual or standard care. ‘Usual or standard care’ was defined as any care where targeted medication reconciliation was not undertaken as an intervention, or where, if an intervention was conducted, it was not provided by a pharmacist. Along with duplicate references, and other studies that did not satisfy the inclusion criteria and were not medication reconciliation studies, we excluded the following types of studies: other medication reconciliation practices (eg, nurse-led) or practices as part of a multicomponent intervention (eg, medication therapy management), case studies, systematic reviews, qualitative outcomes and non-research articles. Abstracts from conferences and full-texts without raw data available for retrieval were not considered. Therefore, the studies selected for inclusion and exclusion assessment were randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental studies with a control group, and before-and-after studies that evaluated pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programmes at hospital transitions. The titles and abstracts were screened by one author (ABM), and studies identified for full-text review and selected according to inclusion criteria were agreed on by the second (AJM) and third reviewer (JEB).

Data extraction

One review author (ABM) was responsible for data extraction from full-texts, using a modified adopted Cochrane EPOC data collection checklist,33 including quality assessment of studies. The following information was extracted from each included study: name of first author, year of publication, country and setting where the study was conducted, study design, sample size, target of intervention, patient characteristics, components of intervention, and relevant outcomes and results. If insufficient details were reported, study authors were contacted for further information.

Outcomes and statistical analysis

Our analysis included studies that reported at least one of these end points: healthcare utilisation (readmission, ED visit and composite readmission, and/or ED visit), mortality and ADE-related hospital visits, compared with usual care in the other arm; and using at least 30 days of follow-up. Studies were eligible for meta-analysis if such end point could be extractable. We analysed data in accordance with the Cochrane handbook.34 Together with 95% CIs for each outcome, we derived the relative risk and weighted mean differences for dichotomous and continuous variables, respectively.

After we combined data, the analyses were conducted with Cochrane Review Manager (RevMan) V.5.3 software (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). We performed separate analyses for each outcome measured compared with usual care. We synthesised the results by constructing a forest plot using a random effects model for each of the outcomes. We analysed intention-to-treat data whenever available. The Mantel-Haenszel risk ratio (RR) summary estimate was determined for outcome measures of dichotomous variables and the weighted mean difference was calculated for continuous data variables. To confirm the reliability of the summary estimate, 95% CIs were calculated. Since the analyses included medication reconciliation interventions with multiple components, different designs and follow-up periods, we set a priori that might be associated with some variation in the outcomes between the studies. When there were at least five studies per outcome, subgroup analyses were carried out according to methodological design factors (RCT and non-randomised studies) and outcome timing (duration of follow-up). For studies that reported outcomes at a different duration, the longer follow-up period was taken in the analysis, if there was no difference in the summary estimate. Otherwise, meta-analysis was performed separately for the long-duration and short-duration subgroups. We assessed statistical heterogeneity among studies through calculating τ2, χ2 (Q), I2 and p value. We conducted sensitivity analysis to check the stability of summary estimates to outliers and the change in I2 when any of the studies were withdrawn from the analysis. We evaluated publication bias by inspection of funnel plot, and Begg-Mazumdar and Egger's test using Comprehensive Meta-analysis, V.3 (Biostat, Englewood, New Jersey, USA). In all analyses, p value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

We assessed the risk of bias of individual studies with EPOC risk of bias tool.33 The main domains considered were random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment, attrition and reporting biases. We also determined whether groups were balanced at baseline in terms of characteristics and outcomes. Included studies were evaluated for each domain and a quality scoring was then calculated for each study. Studies with ‘clear data’ on each of the domains were given a score of 1, and studies were assigned a point score out of the maximum of 9 (9 domains were included in the risk of bias assessment).

Results

Identification and selection of studies

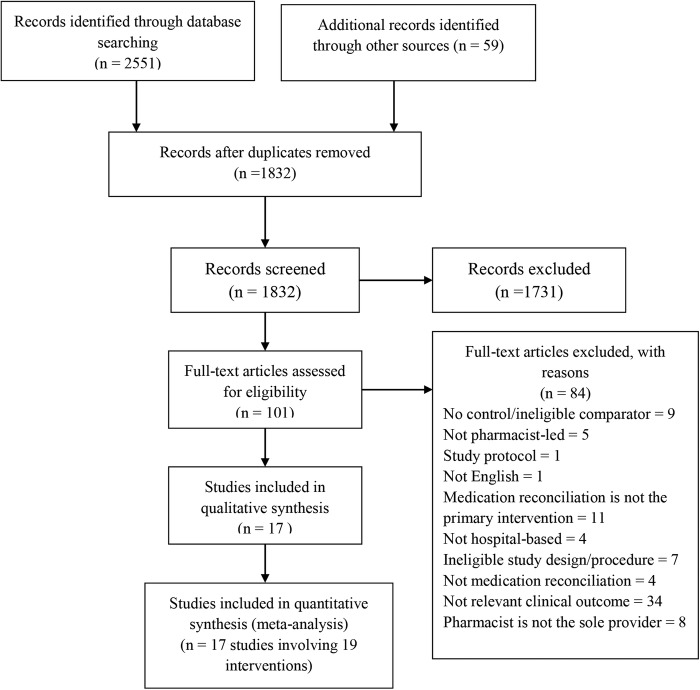

We identified a total of 2551 citations from searches in the electronic databases and 59 additional records were identified in reference lists of included studies. After removal of duplicate records, title and abstract screening was applied on 1832 publications. After title and abstract review, 1731 publications did not meet the inclusion criteria—the focus for the majority of studies was not related to medication reconciliation interventions. The remaining 101 publications were obtained in full-text and assessed for inclusion. Most full-text articles were excluded either due to reporting of a different outcome of interest (n=34) or because medication reconciliation was not the primary intervention (n=11) (see online supplementary appendix B). After applying all the inclusion criteria, we finally included 17 articles (figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the selection of eligible studies.

Characteristics of included studies

Major characteristics of the included studies are presented in table 1. They were randomised controlled trials (n=8, 47%), before-and-after studies (n= 6, 35%) and non-randomised controlled trials (n= 3, 18%). The majority of the studies were conducted in the USA (11 studies),35–45 and the remainder were in Sweden (3 studies),46–48 Ireland (2 studies)49 50 and Australia (1 study).51 The studies had been conducted between 2002 and 2014. The included studies involved a total of 21 342 adult patients of various ages with sample sizes ranging from 41 to 8959 individuals. No studies in paediatrics were identified. Only three studies were confined to multicentre.38 49 51 Most studies reported outcomes up to 30 days of follow-up after selection of eligible patients; only six studies37 46–50 reported longer follow-up of 3-month or more. Interventions were initiated at different care transitions; most were conducted at multiple transitions,35 37–40 42 44 46–51 and all studies targeting a single transition intervention were carried out at hospital discharge.36 41 43 45

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author, Year | Country, Setting | Study design | Intervention | Comparator | Target of intervention | Inclusion | Exclusion | Components of intervention | Comparator | Follow-up Period |

Relevant outcomes | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderegg et al 201435 | USA, single centre | Before–after | 1664 | 1652 | Admission, discharge | Age 18 years or older, discharge from internal medicine, family medicine, cardiology, or orthopaedic surgery medical | Mental illness/alcohol or drug use; discharge to a rehabilitation unit/long-term care facility, readmission for chemotherapy/radiation therapy/rehabilitation therapy | Admission MedRec, Discharge MedRec, patient education, medication calendar | Control group (admission MedRec as needed) | 30 days | Readmission, Readmission and/or ED visit | 30-day readmission and/or ED visit (general population): NS; 30-day readmission (high-risk): 12.3% (I) vs 17.8% (U), p=0.042 |

| Bolas et al 200450 | Ireland, single centre | RCT | 81 | 81 | Inpatient stay, discharge, postdischarge | Age 55 years or older, at least 3 regular medications | Transfer to another hospital or nursing home, unable to communicate, mental illness or alcohol-related admission, follow-up was declined | Medication liaison service (comprehensive medication history, discharge letter faxed to GP and community pharmacist, medicines record sheet, discharge counselling, home visit/telephone call) | Standard clinical pharmacy service (not include discharge counselling and liaison service) | 3 month | Readmission, hospital stay (following readmission) | Readmission rate: p>0.05; Length of stay: p>0.05 |

| Eisenhower 201436 | US, single centre | Before–after | 25 | 60 | Discharge | Age 65 years or older, with history of COPD | Left the hospital without medical advice, death within 30 days of discharge | MedRec at discharge, Medication reconciliation form, discharge summary | Usual care (pharmacist was not present during baseline data collection) | 30 days | Readmission | Readmission rate: 16% (I) vs 22.2% (U) |

| Farris et al 2014 37 | USA, Single centre | RCT | Minimal=312 Enhanced=311 |

313 | Admission, inpatient stay, discharge | 18 years or older, English or Spanish speaker, diagnosis of HPN, hyperlipidaemia, HF, CAD, MI, stroke, TIA, asthma, COPD or receiving oral anticoagulation | Admission to psychiatry, surgery or haematology/oncology service, could not use a telephone, had life expectancy <6 months, had dementia or cognitive impairment | Admission MedRec, patient education during inpatient stay, discharge counselling, discharge medication list, telephone call, care plan faxed to primary care physician/community pharmacist | Usual care (admission MedRec, nurse-led discharge counselling and medication list) | 90 days | ADEs, readmission, ED visit, readmission and/or ED visit | 16% experienced an AE, Healthcare utilisation at 30 days and 90 days: NS |

| Gardella et al 201238 | US, multicentre | Before–after | 1624 | 7335 | Preadmission to post discharge | NA | NA | Preadmission medication list, patient education | Historical control group (preadmission medication list gathered by nurse) | 60 days | ADE, ED visits and readmission | 30-day readmission: 6% (I) vs 13.1% (U) (OR 2.34, 95% CI 1.87 to 2.94, p<0.001); 60-day readmission: 2.7% (I) vs 7.7% (U) (OR 3.02, 95% CI 2.18 to 4.19, p<0.001) |

| Gillespie et al 200946 | Sweden, single centre | RCT | 182 | 186 | Admission, inpatient stay and discharge | Age 80 or older | Previous admission during the study period | Admission MedRec, discharge counselling, medication review, faxing discharge summary to primary care physicians, telephone follow-up at 2 months | Usual care (without pharmacist involvement) | 12 month | Readmissions, ED visits, mortality | Readmissions: 58.2% (I) vs 59.1% (U) (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.4); ED visits per patient: 0.35 (I) vs 0.66 (U) (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.75) |

| Hawes et al 201439 | US, single centre | RCT | 24 | 37 | Discharge and post discharge | High-risk patients ( HF, COPD, hyperglycaemic crisis, stroke ,NSTEM, more than 3 hospitalisations in the past 5 years., 8 or more medications on discharge) | Age <18 years, inability to communicate in English, unable to follow-up (no transportation and no telephone access), transfer to facilities other than primary care, decisional impairment, incarceration | Post discharge medication reconciliation | Usual care (with no pharmacist intervention) | 30 days | Readmission, ED visit, readmission and /or ED visit | ED visit: 0 (I) vs 29.7% (U), p=0.004; Readmission: 0 (I) vs 32.4% (U), p=0.002; Composite of hospitalisation or ED visit: 0 (I) vs 40.5% (C), p<0.001 |

| Hellstrom et al 201147 | Sweden, single centre | Before–after | 109 | 101 | Admission, inpatient stay, discharge | Age 65 years or older, at least one regular medication | Staying during the implementation period | LIMM model, admission and discharge MedRec, medication review and monitoring, quality control of discharge MedRec | Standard care (no formal MedRec by clinical pharmacists) | 3 month | Readmission and ED visit,ADE-related hospital visit | ED visit and readmission: 45/108 (I) vs 41/100 (U) Mortality, 3 month: 9/108 (I) vs 9/100 (U) ADE-related revisit: 6/108 (I) vs 12/100 (U) |

| Hellstrom et al 201248 | Sweden, single centre | Before–after | 1216 | 2758 | Admission, inpatient stay | High-risk patients (age ≥65 years with any of HF, RF) | NA | Admission MedRec, structured medication reviews, follow-up at least two times a week | Usual care (no clinical pharmacists working in the wards) | 6 month | ED visits, hospital admissions and mortality | ED visit: 48.8% (I) vs 51.3% (U) (HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.04); All ED visits, hospitalisation or death: 58.9% (I) vs 61.2% (U) (HR 0.96, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.04) Mortality: 18.2% (I) vs 17.3% (U), p=0.55 |

| Koehler et al 200940 | US, single centre | RCT | 20 | 21 | Admission, discharge and post discharge | Age 70 years or older, ≥5 medications, ≥3 chronic comorbid conditions, assisted living, English language, phone contact | Primarily surgical procedure, life expectancy ≤6 months, residence in long-term care facility, refusal to participate, not enrolled within 72 h. | Targeted care bundle, medication reconciliation and education, follow-up call, enhanced discharge form | Usual care (nurse and care coordination staff providing care) | 60 days | Readmission and/or ED visits | 30 days readmission/ED visits: 2/20 (I) vs 8/21 (U), p= 0.03; 60days readmission/ED visits: 6/20 (I) vs 9/21 (U), p= 0.52 |

| Pal et al 201341 | US, single centre | NRCT | 537 | 192 | Discharge | Age 18 years or older, at least 10 regular medications | NA | Patient counselling, pharmacist medication reconciliation, medication calendar | Usual care (without discharge review by pharmacist) | 30 days | Readmission | 30 days readmission: 16.8% (I) vs 26.0% (U), p=0.006 ADE prevented: 52.8% |

| Schnipper et al 200642 | US, single centre | RCT | 92 | 84 | Inpatient stay, discharge, post discharge | Discharge to home, contacted 30 days after discharge, spoke English, cared for primary care physician/internal medicine resident | NA | Discharge medication reconciliation, telephone follow-up, medication review, standard email template, patient counselling | Usual care (medication review by a pharmacist and discharge counselling by a nurse) | ADEs-related hospital visit, readmission and/or ED visit | Preventable ADE: 1% (I) vs 11% (U), p=0.01; ED visit/readmission: 30% (I) vs 30% (U), p>0.99; preventable medication-related healthcare utilisation: 1% (I) vs 8% (U), p= 0.03 | |

| Scullin et al 200749 | Ireland, multicentre | RCT | 371 | 391 | Admission, inpatient stay, discharge | Age 65 years or older, at least 4 regular medications, taking antidepressants, previous admission in the past 6 months, taking intravenous antibiotics | Scheduled admissions and admissions from private nursing homes | Integrated medicines management service admission and discharge MedRec, inpatient medication review and counselling, telephone follow-up | Usual care (did not receive integrated medicines management service) | 12 month | Length of hospital stay, readmission | LoS reduced by 2 days for intervention vs usual care, p=0.003 Readmissions per patient: 0.8 (I) vs 1 (U) |

| Stowasser et al 200251 | Australia, multicentre | RCT | 113 | 127 | Admission, discharge | Return to the community following discharge | Outpatients, discharge to hostel or nursing home, previous enrolment, unable to provide consent and follow-up | Medication liaison service—medication history confirmation with community healthcare professionals (telephone, faxing), 30 days post follow-up | Usual care (no medication liaison service) | 30 days | Mortality, readmission, ED visit | Mortality, 30 days: 2/113 (I) vs 3/127 (U): NS Readmissions: 12/113 (I) vs 17/127 (U) ED visit per patient: 7.54 (I) vs 9.94 (U) |

| Walker et al 200943 | US, single centre | NRCT | 138 | 366 | Discharge, post discharge | Age 18 years or older, 5 or more regular medications, receiving 1 or more targeted medications, having 2 or more therapy modification, unable to manage their medication, receiving a medication requiring therapeutic drug monitoring | Non-English speaking, stay of 21 days or longer | Patient interviews, follow-up plan, medication counselling, telephone follow-up | Usual care (nurse-led service) | 30 days | Readmission, ED visit, readmission and/or ED visit | Readmission, 14 days: 12.6% (I) vs 11.5% (U), p=0.65; Readmission, 30 days: 22.1% (I) vs 18.0% (U), p=0.17; Readmissions and/or ED visits: 27.4% (I) vs 25.7% (U), p= 0.61 |

| Warden et al 201444 | US, single centre | Before–after | 35 | 115 | Admission, inpatient stay, discharge | Age 18–85 years, systolic dysfunction (EF ≤40) | Diastolic dysfunction, valve replacement/left ventricular assist device | Medication reconciliation (admission and discharge), discharge instructions, telephone follow-up | Historical control group (physicians—admission MedRec; nurses- discharge counselling) | 30 days | Readmission | All cause readmission, 30-day :17% (I) vs 38% (U) (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.96, p=0.02), 30 days HF-related readmission: 6%(I) vs 18% (U) (RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.27, p=0.11) |

| Wilkinson et al 201145 | US, single centre | NRCT | 229 | 440 | Discharge | Age 18 years or older, English speaking, patients with depression, receiving high-risk medications and polypharmacy, poor health literacy, having an absence of social support, prior hospitalisation within the past 6 months | Refusal of pharmacist education, transfer to a skilled nursing facility, or discharge when the pharmacist was not available | Medication history at admission, during hospitalisation and discharge, patient education on discharge | Control group (pharmacists not provide medication counselling at discharge) | 30 days | Readmission | Readmission rate: 15.7% (I) vs 21.6% (U) (RR 0.728, 95% CI 0.514 to 1.032, p =0.04) |

ADE, adverse drug event; CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; D, days; ED, emergency department; EF, ejection fraction; GP, general practitioner; HF, heart failure; HPN, hypertension; I, intervention; IV, intravenous; LIMM, Lund Integrated Medicines Management; LoS, length of stay; MedRec, medication reconciliation; MI, myocardial infarction; NA, not available; NS, non-significant; NSEMI, non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; RCT, randomised controlled trials; RF, renal failure; RR, relative risk; TIA, transit ischaemic attack; U, usual care.

Most studies recruited high-risk patients (including elderly patients, patients with multiple medications and patients at risk of medication-related events). Five studies36 37 39 44 48 focused on a specific patient population, mainly patients with heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Methodologically, one study35 stratified patients into two groups: general population and high-risk patients, and another study37 randomised the population into two levels of intervention: minimal and enhanced.

Some studies compared comprehensive medication reconciliation programmes, for example, multifaceted interventions including telephone follow-up and/or home visit,44 48 51 and patient counselling,35 38 41 45 or both telephone/home visit and patient counselling.37 40 42 43 46 49 50 After medication reconciliation, a few studies42 46–49 additionally included a formal medication review. Comparator groups in the included studies were varied, and most studies compared medication reconciliation interventions with a usual care group that did not receive pharmacist-led intervention.

Risk of bias assessment

Patients included in the study were similar in baseline characteristics except in five studies,36 38 39 45 48 which were not clear or different in patient characteristics. However, in only three studies43 48 51 were baseline clinical outcomes reported or was some form of adjustment analysis performed. Eight out of 17 studies37 39 40 42 46 49–51 provided enough details on randomisation procedure to be judged as adequate. Among these studies, allocation concealment was fully described in all reports except one.51 In all but three studies43 45 50 had care providers and outcome assessors been blinded or objective health outcomes reported. Five studies37 41 47 48 51 achieved more than 80% complete follow-up. However, only a few studies examined the impact of losses to follow-up or drop-out. High-risk of contamination was suspected in four studies.35 37 41 47 At least one of our outcomes of interest was selectively reported in four studies.36 49–51 Overall, on a scale of 9, quality of randomised controlled trials falls within a range of 4–8, whereas for non-randomised controlled trials a lower range of 1–5 score was attained (see online supplementary appendix C).

Effect of interventions

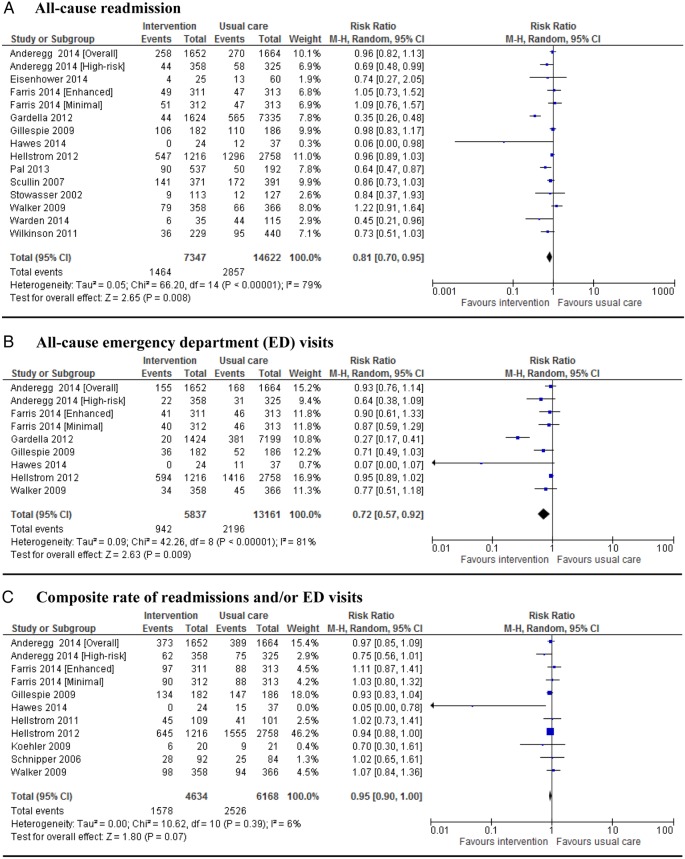

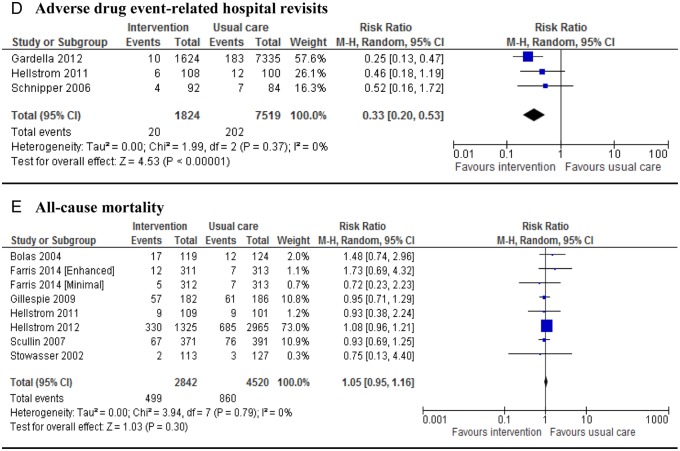

Of the 14 studies that reported data on all-cause readmissions, 13 were eligible for meta-analysis. One study35 measured this outcome for a high-risk population separately; and another study37 reported it for two different interventions. Thus, 15 interventions were meta-analysed. Eight studies reported this outcome at 30 days,35 36 39 41 43–45 51 while three46 48 49 reported long-term data and two studies37 38 reported both. Seven studies35 38 39 41 44 45 49 showed a significant reduction (p<0.05) in rehospitalisations although two39 44 of them had a very small sample size. The pooled RR (n=21 969 patients) across all studies was 0.81 (95% CI 0.70 to 0.95). However, the results of these studies for this end point are substantially heterogeneous (figure 2A). With regard to all-cause emergency department (ED) contacts, seven of eight studies35 37–39 43 46 48 that measured ED visit as an outcome were pooled. Considering studies that gave two sets of data, nine interventions were meta-analysed. The pooled analysis across all interventions showed some significant difference between the intervention and usual care (RR 0.72; 95% CI 0.57 to 0.92; figure 2B). Evidence showed extreme heterogeneity in this outcome; however, the findings were different when the study by Gardella et al38 was removed; there was no heterogeneity without affecting the significance difference (p=0.25; I2=22%, RR 0.89; 95% CI 0.79 to 0.99). Nine studies35 37 39 40 42 43 46–48 that reported composite all-cause readmission and/or ED visit showed no difference in pooled analysis (RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.90 to 1.00 figure 2C). Only three studies38 42 47 were meta-analysed for ADE-related hospital revisits. One study46 did not give data in a suitable form. The pooled result showed a substantial reduction of 67% in hospital revisits (pooled RR 0.33; 95% CI 0.20 to 0.53) when pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programmes were implemented (figure 2D). Seven studies37 46–51 gave eight separate sets of data for all-cause mortality that had been reported after 30 days to 12 months of follow-up. However, information on mortality from Bolas et al50 and Farris et al37 was not their primary outcome of interest; nevertheless, we included it in our meta-analysis. Overall, there was no significance difference between the two groups in terms of all-cause mortality (RR 1.05; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.16) (figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Forest plots of intervention effects on the proportion of patients with all-cause readmission (A), emergency department (ED) visits (B), composite rate of readmissions and/or ED visits (C), adverse drug event-related hospital revisits (D) and mortality (E). Pooled estimates (diamond) calculated by the Mantel-Haenszel random effects model. Horizontal bars and diamond widths represent 95% CIs. Anderegg et al35 stratified patients into two groups: general population and high-risk patients. Farris et al37 randomised the population into different levels of intervention: minimal and enhanced.

Figure 2.

Continued.

Other outcomes

Studies reporting other clinically important outcomes are summarised in table 2. Some studies46–49 furnished information on the proportion of patients who did not revisit the hospital. The intervention group in the three studies46 48 49 showed a trend towards an increase in the number of patients who did not revisit the hospital for any causes, and the overall pooled analysis was statistically significant (RR 1.10; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.17). There were no significance differences between the intervention and usual care in terms of other relevant clinical outcomes: length of stay after readmission, readmission per patient, ED visit per patient and proportion of patients with ADEs.

Table 2.

Other clinically relevant outcomes

| Outcome | Number of studies | Number of patients | RR | CI | WMD | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients who did not revisit hospital | 4 | 5314 | 1.10* | (1.03 to 1.17)† | ||

| Hospital stay (after readmission) | 2 | 803 | −0.57 | (−5.32 to 4.17)‡ | ||

| Readmission per patient | 3 | 1370 | −0.12 | (−0.24 to 0.01)‡ | ||

| ED visit per patient | 2 | 4342 | −0.15 | (−0.53 to 0.23)‡ | ||

| Patients with ADE | 3 | 1401 | 0.94 | (0.75 to 1.20)‡ |

*RR is >1 when the intervention increased the number of patients who did not revisit the hospital (ie, it showed success).

†p<0.01.

‡p>0.05.

ADE, adverse drug event; ED, emergency department; RR, risk ratio; WMD, weighted mean difference.

Sensitivity analysis

A one-on-one removal of studies in the meta-analysis did not affect findings in all outcomes except for composite readmission and/or ED visit. A meta-analysis for composite readmission/ED visit showed that only when the study by Faris et al (Enhanced)37 or Hawes et al39 was removed did the result show a significant pooled summary estimate with similar risk ratio (RR 0.95; p=0.02 and 0.03, respectively).

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis comparing studies that reported all-cause readmissions at earlier versus longer follow-up period showed different patterns of effect: the effect of intervention was not statistically significant for longer follow-up subgroups (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.06, p=0.14), whereas in earlier follow-up subgroups, the effect was significant (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.98, p=0.03). However, there was no significant difference between these two subgroups. In addition, non-randomised studies showed a significant reduction in all-cause readmission (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.94, p=0.01) and all-cause ED visit (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.97, p=0.03), but there was no difference in terms of study design with these outcomes. As opposed to what has been observed in the entire analysis, the composite outcome seemed to have a slight significant reduction in non-randomised studies (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.00, p=0.04); though there was no difference between the subgroups (see online supplementary appendix D).

Publication bias

We examined the potential for publication bias by constructing a funnel plot and through statistical tests. There was some indication of asymmetry—particularly for all-cause ED visits—in the funnel plot and, therefore, there was some publication bias, as evidenced by the Egger's (p=0.04) and Begg's tests (p=0.01) in this outcome. We did not find any significant evidence of bias in the other outcomes, as shown by Egger's test value of 0.08 for all-cause readmission, 0.57 for composite readmission/ED visit and 0.83 for all-cause mortality; this was further supported by Begg's test p value of 0.13, 0.35 and 0.71, respectively (see online supplementary appendix E).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to investigate the effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programmes on clinical outcomes at hospital transitions. This review has shown better outcomes in favour of pharmacist-led interventions. We found a substantial reduction in the rate of all-cause readmissions (19%), all-cause ED visits (28%) and ADE-related hospital revisits (67%). However, pooled data on mortality and composite readmission/ED visit favoured neither the intervention nor the usual care. Not only were patients allocated to the intervention group readmitted or not only did they revisit the hospital less frequently, but patients free of any events after hospital discharge also increased (RR 1.10; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.17).

No previous reviews have conclusively and consistently shown effectiveness of medication reconciliation interventions, be it in primary care,52 long-term settings53 or hospital transitions.30 31 Particularly, reviews from hospital-initiated medication reconciliation interventions searched the available literature on medication reconciliation strategies and impact on patient safety, and summarised the evidence that medication reconciliation alone was not strong enough to reduce post discharge hospital utilisation.30 31 It was not clear to support the effectiveness of such interventions in the hospital setting. However, we believe that the influence of pharmacist's in healthcare utilisation was diluted among those various medication reconciliation strategies and, thus, specifically assessing the effect of pharmacist in medication reconciliation is an important consideration.

Although Thomas et al54 did not find a significant effect in reduction of readmissions due to medication-related problems, our review showed that pharmacists’ influence in preventing ADE-related hospital revisits was more impactful than any of the outcomes measured. This might be because medication reconciliation picks patients with discontinued medication more powerfully, where this is the case for studies reporting this outcome.43 47 Other studies also showed that medication discontinuity is the most common reason for discrepancy-related ADE.55 56 Although the study by Gillespie et al46 was not included in the meta-analysis of this outcome, it showed a much higher reduction of 80% in medication-related readmissions in the intervention group than in the control group. Readmissions were frequent in earlier follow-up periods. This is as opposed to a review by Kwan et al,31 where harm due to medication discrepancies occurred only some months after discharge. However, for most studies, the duration of follow-up was short; only one-third of interventions followed patients for longer than 30 days. Therefore, it might be difficult to come to a conclusion, as there was no sustained benefit from the intervention, and this was supported by non-significant differences between the subgroups. Moreover, non-randomised studies showed a slight significant reduction in all-cause ED visit and readmission and composite outcome, but there was no difference in terms of study design with these outcomes. Otherwise, pooled estimates showed consistent results in all of these three outcomes, regardless of the study design and duration of follow-up. However, care should be taken in interpreting the results as some of the influence of observational studies on the success of outcome was clear, and their heterogeneity should be taken into consideration.

Some of the studies, as part of their intervention, consisted of intermingled components, and the difficulty in ascertaining the success of pharmacist-led intervention is due only to medication reconciliation. After medication reconciliation, for example, medication review as intervention component was added in some studies. Previous systematic reviews that focused on medication review57 58 raised a debate as to the impact of medication reviews in general, and pharmacist-led medication reviews in particular. A review by Holland et al,57 where only 8 of the 32 included studies were hospital-based and only 2 of these had extensive medical team involvement at hospital transitions, did not support the evidence for pharmacist-led medication review. On the other hand, one of the issues raised in a Cochrane review58 was that medication review had varied and wider meaning, and did not stand alone. Prior to medication review, it is medication reconciliation that is practiced routinely at hospital transitions and, thus, considering medication review without ensuring the most accurate list of a patient's current medications would be theoretical. This would strengthen our anticipation that interventions with medication reconciliation might be as equally effective as those with mixed interventions.

A number of recent studies have investigated medication reconciliation interventions at the level of real practice models or in integrated management of medicines.47–49 Medication reconciliation interventions are complex interventions targeting fragments of services across the entire spectrum of care transitions, and thus take time and effort, but the outcome of safe patient transition is well worth it. This review further consolidates pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programmes might contribute to quality transitions in combinations of those multifaceted components.

Limitation of the study

There are a number of limitations to this study. First, most studies included high-risk patients, and we did not confirm which patients benefited most from such interventions. Various definitions pertaining to high-risk were employed, including patients with specific disease state, polypharmacy, older age and patients at risk of hospitalisation. Second, interventions target different transitions; we could not take into account this effect in our meta-analysis. For instance, previous prospective studies showed varied results on the rate of medication discrepancies from 30–55% during admission,59–62 to 35–71% during discharge.4 63 64 Coleman et al65 showed that patients with medication discrepancies have significantly high rates of readmission. Thus, if this value is extrapolated to clinical outcomes, there might be some variation among studies with respect to these outcomes at the different care transitions. Additionally, few studies were carried out in hospitals where medication reconciliation had already been implemented in some defined areas. Therefore, future studies should evaluate specific areas suited to pharmacist services that would benefit patients the most. Third, most of the studies were single centre evaluations, and there were a few studies with a small number of patients. Considering the success rates within small single centre studies raises an issue about bias. Our included studies were not free of bias and most possessed moderate quality, which leaves the findings open to criticism—for example, Gardella et al,38 in the ADE-related hospital visit, and Hellström et al,48 in the mortality forest plots, accounted for a large proportion of the studied subjects, yet these studies possessed low quality score. Fourth, the lack of homogeneity in the data from this meta-analysis confirms the complexity of medication reconciliation and warrants further investigation. We attempted to investigate the sources of variation between studies, but were unable to explain much of it. We were also unable to assess interactions between medication reconciliation and components of interventions. For example, integrated care models may be particularly effective for improving care for some of the interventions, but not for other types, and a pooled analysis would not identify such interactions. Despite these limitations, our meta-analyses showed that interventions that contain one or more elements of medication reconciliation can improve outcomes at hospital transitions.

We also note that only published studies were included in our work. However, the funnel plot asymmetry and statistical tests suggest that the impact of bias was less likely to have a significant effect on the findings. Only articles published in English were assessed for this review. Potentially, there may have been studies, such as that by Sánchez Ulayar et al,66 published in non-English journals, involving interventions for improving care transitions. In addition, research disseminated through the grey literature, such as conference papers and unpublished reports, was not considered.

Conclusion

The results of this meta-analysis indicate that a pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programme at hospital transitions decreases ADE-related hospital revisits, all-cause readmissions and ED visits. However, the effect on mortality and composite all-cause readmission/ED visit is inconclusive based on the current body of evidence, though improvements in the majority of studies were demonstrated. Future research is needed to assess whether improvements in such outcomes can be achieved with this programme and to determine what/which components of the intervention are necessary to improve clinical outcomes. Although our results showed that pharmacist-led medication reconciliation was beneficial at care transitions, we still need further research with robust, large randomised control trials of excellent quality to conform our conclusion. Overall, our findings support the implementation of a pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programme that includes some components aimed at improving medication safety.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Asres Berhan for his comments on the data analysis and interpretation, and statistical advice on using the meta-analysis software. The authors would also like to acknowledge Lorraine Evison for her invaluable contributions in the electronic database searching and abstract screening.

Footnotes

Contributors: ABM was responsible for the study conception and design, under the supervision of JEB. The literature search, abstract screening, study and data extraction were undertaken by ABM with further confirmation by JEB. ABM carried out the initial analysis and drafted the first manuscript. JEB and ABM critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Our study is an investigation of the literature, and does not need ethical approval for retrieving the already available public content.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Medication reconciliation review. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/MedicationReconciliationReview.aspx (accessed 30 Dec 2014).

- 2.Rozich JD, Howard RJ, Justeson JM et al. Standardization as a mechanism to improve safety in health care. Jt Comm J Qual Saf 2004;30:5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cornish PL, Knowles SR, Marchesano R et al. Unintended medication discrepancies at the time of hospital admission. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:424–9. 10.1001/archinte.165.4.424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong JD, Bajcar JM, Wong GG et al. Medication reconciliation at hospital discharge: evaluating discrepancies. Ann Pharmacother 2008;42:1373–9. 10.1345/aph.1L190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pippins JR, Gandhi TK, Hamann C et al. Classifying and predicting errors of inpatient medication reconciliation. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:1414–22. 10.1007/s11606-008-0687-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herrero-Herrero JI, García-Aparicio J. Medication discrepancies at discharge from an internal medicine service. Eur J Intern Med 2011;22:43–8. 10.1016/j.ejim.2010.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geurts MM, Talsma J, Brouwers JR et al. Medication review and reconciliation with cooperation between pharmacist and general practitioner and the benefit for the patient: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012;74:16–33. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04178.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allende Bandrés MÁ, Arenere Mendoza M, Gutiérrez Nicolás F et al. Pharmacist-led medication reconciliation to reduce discrepancies in transitions of care in Spain. Int J Clin Pharm 2013;35:1083–90. 10.1007/s11096-013-9824-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howard RL, Avery AJ, Howard PD et al. Investigation into the reasons for preventable drug related admissions to a medical admissions unit: observational study. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12:280–5. 10.1136/qhc.12.4.280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Witherington EM, Pirzada OM, Avery AJ. Communication gaps and readmissions to hospital for patients aged 75 years and older: observational study. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:71–5. 10.1136/qshc.2006.020842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dedhia P, Kravet S, Bulger J et al. A quality improvement intervention to facilitate the transition of older adults from three hospitals back to their homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1540–6. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnipper JL, Hamann C, Ndumele CD et al. Effect of an electronic medication reconciliation application and process redesign on potential adverse drug events: a cluster-randomized trial. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:771–80. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:178–87. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joint Commission on Accreditation for Healthcare Organizations. National Patient Safety Goals 2006. http://www.jointcommission.org/Improving_Americas_Hospitals_The_Joint_Commissions_Annual_Report_on_Quality_and_Safety_-_2006/

- 15.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Technical patient safety solutions for medicines reconciliation on admission of adults to hospital London, 2007. (NICE/NSPA/2007/PSG001). http://www.nice.org.uk/PSG001 (accessed 30 Dec2014). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canadian Council on Health Services Accreditation. Patient Safety Goals and Required Organizational Practices Ottawa, 2004. http://www.accreditation.ca (accessed 30 Dec 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. Medication reconciliation. http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/medication-safety/medication-reconciliation/ (accessed 30 Dec 2014).

- 18.Durán-García E, Fernandez-Llamazares CM, Calleja-Hernández MA. Medication reconciliation: passing phase or real need? Inter J Clin Pharm 2012;34:797–802. 10.1007/s11096-012-9707-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Canadian Agency for Drugs and Techonlogies in Health. Medication reconciliation at discharge: a review of the clinical evidence and guidelines 2012. https://www.cadth.ca/medication-reconciliation-discharge-review-clinical-evidence-and-guidelines (accessed 24 Nov 2015).

- 20.Giménez Manzorro Á, Zoni AC, Rodríguez Rieiro C et al. Developing a programme for medication reconciliation at the time of admission into hospital. Int J Clin Pharm 2011;33:603–9. 10.1007/s11096-011-9530-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schnipper JL, Liang CL, Hamann C et al. Development of a tool within the electronic medical record to facilitate medication reconciliation after hospital discharge. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18:309–13. 10.1136/amiajnl-2010-000040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore P, Armitage G, Wright J et al. Medicines reconciliation using a shared electronic health care record. J Patient Saf 2011;7:148–54. 10.1097/PTS.0b013e31822c5bf9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bédard P, Tardif L, Ferland A et al. A medication reconciliation form and its impact on the medical record in a paediatric hospital. J Eval Clin Pract 2011;17:222–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01424.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Winter S, Vanbrabant P, Spriet I et al. A simple tool to improve medication reconciliation at the emergency department. Eur J Intern Med 2011;22:382–5. 10.1016/j.ejim.2011.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Winter S, Spriet I, Indevuyst C et al. Pharmacist- versus physician-acquired medication history: a prospective study at the emergency department. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:371–5. 10.1136/qshc.2009.035014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feldman LS, Costa LL, Feroli ER et al. Nurse-pharmacist collaboration on medication reconciliation prevents potential harm. J Hosp Med 2012;7:396–401. 10.1002/jhm.1921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenwald JL, Halasyamani L, Greene J et al. Making inpatient medication reconciliation patient centered, clinically relevant and implementable: a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps. J Hospital Med 2010;5:477–85. 10.1002/jhm.849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eggink RN, Lenderink AW, Widdershoven JW et al. The effect of a clinical pharmacist discharge service on medication discrepancies in patients with heart failure. Pharm World Sci 2010;32:759–66. 10.1007/s11096-010-9433-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galvin M, Jago-Byrne MC, Fitzsimons M et al. Clinical pharmacist's contribution to medication reconciliation on admission to hospital in Ireland. Int J Clin Pharm 2013;35:14–21. 10.1007/s11096-012-9696-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mueller SK, Sponsler KC, Kripalani S et al. Hospital-based medication reconciliation practices: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1057–69. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwan JL, Lo L, Sampson M et al. Medication reconciliation during transitions of care as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:397–403. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303051-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.David Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. , The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). [Data collection checklist and risk of bias]. EPOC Resources for review authors. Oslo: Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services, 2014. http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors (accessed 30 Dec 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higgins JPT, Green S (eds). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderegg SV, Wilkinson ST, Couldry RJ et al. Effects of a hospitalwide pharmacy practice model change on readmission and return to emergency department rates. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2014;71:1469–79. 10.2146/ajhp130686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eisenhower C. Impact of pharmacist-conducted medication reconciliation at discharge on readmissions of elderly patients with COPD. Ann Pharmacother 2014;48:203–8. 10.1177/1060028013512277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farris KB, Carter BL, Xu Y et al. Effect of a care transition intervention by pharmacists: an RCT. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:406–0. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gardella JE, Cardwell TB, Nnadi M. Improving medication safety with accurate preadmission medication lists and postdischarge education. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2012;38:452–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hawes EM, Maxwell WD, White SF et al. Impact of an outpatient pharmacist intervention on medication discrepancies and health care resource utilization in posthospitalization care transitions. J Prim Care Community Health 2014;5:14–18. 10.1177/2150131913502489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koehler BE, Richter KM, Youngblood L et al. Reduction of 30-day postdischarge hospital readmission or emergency department (ED) visit rates in high-risk elderly medical patients through delivery of a targeted care bundle. J Hosp Med 2009;4:211–18. 10.1002/jhm.427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pal A, Babbott S, Wilkinson ST. Can the targeted use of a discharge pharmacist significantly decrease 30-day readmissions? Hosp Pharm 2013;48:380–8. 10.1310/hpj4805-380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:565–71. 10.1001/archinte.166.5.565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walker PC, Bernstein SJ, Jones JN et al. Impact of a pharmacist-facilitated hospital discharge program: a quasi-experimental study. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:2003–10. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Warden BA, Freels JP, Furuno JP et al. Pharmacy-managed program for providing education and discharge instructions for patients with heart failure. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2014;71:134–9. 10.2146/ajhp130103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilkinson ST, Pal A, Couldry RJ. Impacting readmission rates and patient satisfaction: results of a discharge pharmacist pilot program. Hosp Pharm 2011;46:876–83. 10.1310/hpj4611-876 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gillespie U, Alassaad A, Henrohn D et al. A comprehensive pharmacist intervention to reduce morbidity in patients 80 years or older: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:894–900. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hellström LM, Bondesson A, Höglund P et al. Impact of the Lund Integrated Medicines Management (LIMM) model on medication appropriateness and drug-related hospital revisits. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2011;67:741–52. 10.1007/s00228-010-0982-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hellström LM, Höglund P, Bondesson A et al. Clinical implementation of systematic medication reconciliation and review as part of the Lund Integrated Medicines Management model—impact on all-cause emergency department revisits. J Clin Pharm Ther 2012;37:686–92. 10.1111/jcpt.12001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scullin C, Scott MG, Hogg A et al. An innovative approach to integrated medicines management. J Eval Clin Pract 2007;13:781–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00753.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bolas H, Brookes K, Scott M et al. Evaluation of a hospital-based community liaison pharmacy service in Northern Ireland. Pharm World Sci 2004;26:114–20. 10.1023/B:PHAR.0000018601.11248.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stowasser DA, Collins DM, Stowasser M. A randomised controlled trial of medication liaison services—patient outcomes. J Pharm Pract Res 2002;32:133–40. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bayoumi I, Howard M, Holbrook AM et al. Interventions to improve medication reconciliation in primary care. Ann Pharmacother 2009;43:1667–75. 10.1345/aph.1M059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chhabra PT, Rattinger GB, Dutcher SK et al. Medication reconciliation during the transition to and from long-term care settings: a systematic review. Res Social Adm Pharm 2012;8:60–75. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2010.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thomas R, Huntley AL, Mann M et al. Pharmacist-led interventions to reduce unplanned admissions for older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Age Ageing 2014;43:174–87. 10.1093/ageing/aft169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boockvar KS, Carlson LaCorte H, Giambanco V et al. Medication reconciliation for reducing drug-discrepancy adverse events. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2006;4:236–43. 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mergenhagen KA, Blum SS, Kugler A et al. Pharmacist versus physician-initiated admission medication reconciliation: impact on adverse drug events. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2012;10:242–50. 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holland R, Desborough J, Goodyer L et al. Does pharmacist-led medication review help to reduce hospital admissions and deaths in older people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2008;65:303–16. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.03071.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Christensen M, Lundh A. Medication review in hospitalised patients to reduce morbidity and mortality. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev 2013;2:CD008986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coffey M, Mack L, Streitenberger K et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of medication discrepancies at pediatric hospital admission. Acad Pediatr 2009;9:360–5. 10.1016/j.acap.2009.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gleason KM, Groszek JM, Sullivan C et al. Reconciliation of discrepancies in medication histories and admission orders of newly hospitalized patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2004;61:1689–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Salanitro AH, Osborn CY, Schnipper JL et al. Effect of patient- and medication-related factors on inpatient medication reconciliation errors. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:924–32. 10.1007/s11606-012-2003-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Villanyi D, Fok M, Wong RY. Medication reconciliation: identifying medication discrepancies in acutely ill hospitalized older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2011;9:339–44. 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2011.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manias E, Gerdtz MF, Weiland TJ et al. Medication use across transition points from the emergency department: Identifying factors associated with medication discrepancies. Ann Pharmacother 2009;43:1755–64. 10.1345/aph.1M206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grimes T, Delaney T, Duggan C et al. Survey of medication documentation at hospital discharge: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. Ir J Med Sci 2008;177:93–7. 10.1007/s11845-008-0142-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Coleman EA, Smith JD, Raha D et al. Posthospital medication discrepancies: prevalence and contributing factors. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1842–7. 10.1001/archinte.165.16.1842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sánchez Ulayar A, Gallardo López S, Pons Llobet N et al. Pharmaceutical intervention upon hospital discharge to strengthen understanding and adherence to pharmacological treatment. Farm Hosp 2012;36:118–23. 10.1016/j.farma.2011.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010003supp_appendices.pdf (526.9KB, pdf)