Abstract

We present the case of a 30-year-old woman who presented with an 11-year history of chronic occipital headaches and a 12-month history of worsening difficulty speaking and/or swallowing, facial spasms, hearing loss, and dizziness. A large lytic mass was found centered in the left jugular foramen (JF) on computed tomography examination; follow-up magnetic resonance imaging showed an avidly enhancing mass with prominent central flow voids. Histopathologic examination after surgical resection revealed the mass to be a schwannoma. Prominent central vascularity is an unusual presentation for JF schwannomas. Our report provides a review of magnetic resonance imaging features of intrinsic JF lesions relevant to our case.

Keywords: Schwannoma, Paraganglioma, Jugular foramen, Flow voids, MRI, Imaging

Introduction

Schwannomas are benign tumors of nerve sheath origin that most often arise from the superior vestibular branch of the eighth cranial nerve in the cerebellopontine angle [1]. However, schwannomas may rarely originate from the ninth or tenth cranial nerves within the jugular foramen (JF) [2]. The contents of the JF guide a unique differential in the consideration of an intrinsic JF lesion. Besides schwannomas, paragangliomas may arise from scattered collections of paraganglial tissue, and meningiomas may form from an intraforaminal connective tissue layer. Additional considerations include metastatic tumor, primitive neuroectodermal tumor, and jugular vein pseudomass [3], [4].

The imaging characteristics of these lesions are often similar. However, paragangliomas are classically associated with a “salt & pepper” appearance on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) because of multiple areas of signal void interspersed with hyperintense foci due to slow flow or hemorrhage. Accordingly, paragangliomas are highly vascular on angiography [5]. In contrast, schwannomas are typically described as avascular or hypovascular on angiography, without central flow voids on MRI [2], [4], [5]. We describe an unusual case of a JF schwannoma with prominent central flow voids on MRI and present an overview of the relevant imaging findings.

Case report

A 30-year-old woman with a family history of cancer and an 11-year history of chronic occipital headaches presented with a chief complaint of increasing difficulty speaking and reaching high notes whereas singing over the past year. She also reported difficulty swallowing, left-sided facial spasms, left-sided hearing loss, tinnitus, and dizziness. On physical examination, deficits in the left eighth through twelfth cranial nerves were identified.

A contrast-computed tomography (CT) scan of her head was performed for further evaluation and revealed a scalloped expansion of the JF with a mildly enhancing soft tissue mass measuring 2.6 cm in diameter (Fig. 1A). The mass showed intracranial extension to the cerebellopontine angle and extracranial extension into the carotid space (Figs. 1B and C).

Fig. 1.

Enhanced-CT examination showing a mildly enhancing mass in the L-JF with (A) scalloped expansion of the JF (small arrows) with medial extension (large arrow) on bone windows; (B) extracranial extension in the carotid space; and (C) intracranial extension with involvement of the cerebellopontine angle (arrow).

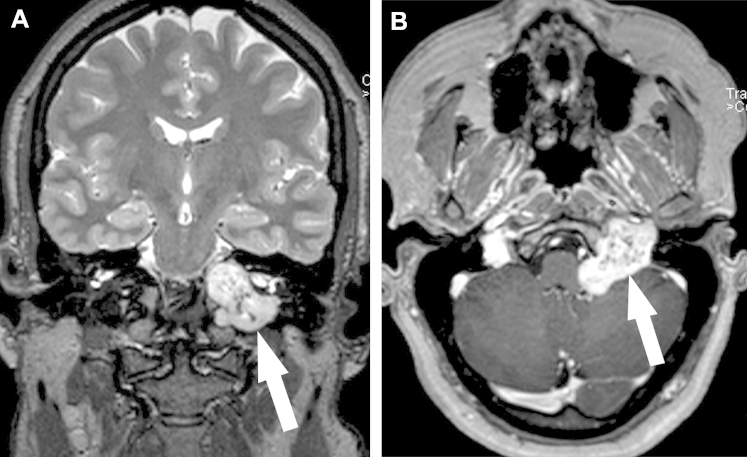

Subsequent MRI examination showed a 3.8 × 3.5 × 3.5 cm3 dumbbell-shaped lesion with a “salt & pepper” appearance on coronal T2W-imaging in the left JF (Fig. 2A), with involvement of the left internal auditory canal, hypoglossal canal, clivus, and cerebellopontine angle. This lesion demonstrated avid enhancement on postcontrast imaging (Fig. 2B). There was associated mass effect on the left medulla and anterior inferior left cerebellum, and obscuration of the left-sided cranial nerves VII-XII. The distal left cervical internal carotid artery just proximal to the horizontal petrous segment was asymmetrically small in caliber, and the left internal jugular vein was not seen.

Fig. 2.

MRI examination showing (A) a dumbbell-shaped lesion with demonstration of “salt & pepper” appearance on coronal T2W imaging (arrow), and (B) an avidly contrast-enhancing mass in the JF with prominent central flow voids corresponding to a “pepper”-like appearance on axial-T1W imaging (arrow).

An elective operative approach was selected. Carotid angiography and tumor embolization were performed before surgery. External carotid angiogram revealed angiographic tumor blush just distal to the origin of the ascending pharyngeal artery anteriorly at the left skull base with vascular supply from the ascending pharyngeal artery (Fig. 3). Postembolization angiogram showed no identifiable residual tumor blush.

Fig. 3.

Carotid angiography showing tumor blush (circle) supplied by a branch of the ascending pharyngeal artery (arrow).

Mastoidectomy and suboccipital craniectomy were performed and both translabyrinthine and retrosigmoid approaches were used to gain access to the tumor. Microsurgical resection of the tumor was performed under intraoperative cranial nerve monitoring, with intentional residual tumor left behind in the inferior pole of the JF and in the internal auditory canal because of indistinct tissue plane between nerve and tumor capsule. Closure was accomplished via abdominal fat graft and titanium plating.

Histopathologic examination showed palisading nuclei and spindle cells, and the sample was positive for S100 protein and negative for neurofibrillary and epithelial stains on immunohistochemistry. The final pathologic diagnosis was schwannoma with no evidence of malignancy. The diagnosis was definitive with no evidence of paraganglioma.

The patient recovered appropriately postoperatively, and was discharged on postoperative day 7. There was minimal improvement from her preoperative clinical symptomatology. The patient returned 3 weeks later complaining of postnasal drip, rhinorrhea, headaches, fever, sore throat, and malaise; a cerebrospinal fluid leak was identified and the patient underwent exploration of the posterior and middle cranial fossae for closure of the defect. The patient was discharged 3 days after the secondary repair, and as of the time of this report is recovering appropriately.

Discussion

JF masses can be classified on the basis of whether they arise from structures within the foramen or external to it, that is, intrinsically or extrinsically [4]. Extrinsic lesions include chordoma, inflammatory lesions, and rhabdomyosarcoma; and intrinsic lesions include paraganglioma, schwannoma, meningioma, metastatic disease, jugular vein pseudomass, and others. Based on the clinical history and imaging characteristics, the differential was considered to be largely comprised of the 2 most common intrinsic tumors of the JF: paraganglioma vs schwannoma [6].

Paragangliomas, also called glomus jugulare tumors when located in the JF, comprise the majority of primary JF tumors [4], [6]. Paragangliomas are said to follow the paths of least resistance, affecting the mastoid air cells, vascular channels, auditory tube, and neural foramina [5]. They may also proliferate into the tympanum, causing destruction of the ossicles and/or the bony labyrinth [4]. The characteristic spread of the tumor leads to a “moth-eaten” pattern of destruction of the temporal bone, which is evident on CT-bone windows. Medial extension and extracranial extension into the carotid space is less common [4].

Paragangliomas are highly vascular tumors which show strong heterogeneous enhancement with contrast agents [5]. On MRI, this vascularity is manifested with prominent flow voids, resulting in the classic “salt-and-pepper” appearance [7]. Angiography may reveal a coarse tumor blush with derivation from the ascending pharyngeal artery and the presence of early venous drainage [4].

JF schwannomas, in contrast to paragangliomas, result in scalloped, sclerotic expansion rather than lytic destruction of the temporal bone [2]. Four presentations of JF schwannomas were identified by Samii et al [8]: type A: primary cerebellopontine angle involvement, type B: primary JF involvement, type C: primary extracranial involvement, and type D: both intracranial and extracranial components resulting in a dumbbell-shaped lesion. Middle ear involvement is rare [2].

On CT imaging, JF schwannomas are most commonly isodense to brain parenchyma, and show strong enhancement upon contrast administration. They typically show low T1 signal, high T2 signal, and marked contrast enhancement on MRI. They do not generally exhibit central flow voids, distinguishing them from paragangliomas, and are correspondingly avascular or hypovascular on angiography [2].

Our case represents an atypical presentation of JF schwannoma. Initially, paraganglioma was suspected because of the classic “salt & pepper” flow voids on MRI, as well as angiographically evident tumor blush. Additional features that also supported paraganglioma included middle ear involvement and the epidemiologic preponderance of paragangliomas in the JF.

However, on reevaluation of neuroimaging, evidence supporting schwannoma could also be identified, particularly in the pattern of growth. There was a scalloped instead of a “moth-eaten” lytic pattern of bony involvement with limited expansion into the mastoid air cells (Fig. 1A); in addition, there was extensive medial extension into the hypoglossal canal and clivus as well as extracranial extension into the carotid space (Samii type D), features less commonly seen in JF paragangliomas [4]. Moreover, the enhancement pattern on CT and tumor blush on angiography was less prominent that would be expected for a paraganglioma, although the vascularity of the tumor ultimately dissuaded us from a diagnosis of schwannoma.

Schwannomas with prominent vascularity have been previously described in the literature, first in the 1970s via angiography [9], [10]. More recent reports have described their appearance on MRI, though they only rarely resemble the findings presented in this report. Bonneville et al [11] described a hypervascular intracisternal schwannoma with early filling enlarged veins as a feature of a malignant lesion, as opposed to the benign lesion in our case. Yamakami et al [12] presented 5 cases of hypervascular vestibular schwannomas with the primary finding of large peripheral flow voids representing large draining veins; whereas 2 of 5 cases showed intratumoral flow voids, their appearance lacked the distinct pattern of hypointensity and hyperintensity characteristic of a “salt & pepper” appearance.

In fact, only 1 instance, Kato et al [13], describes a “salt & pepper” appearance of intratumoral flow voids in schwannomas, though the 2 cases presented were located extracranially. Though previous reports attributed the peripheral flow voids of some schwannomas to enlarged draining veins, Kato ascribes the central vascularity described in his report to the degenerative change seen in “ancient schwannomas,” such as abnormal calcification and hyalinization. However, our case was devoid of these changes on imaging and histopathologic examination, perhaps indicating that the central flow voids in fact represent an identical process as seen in paragangliomas: enlarged arteries supplying a hypervascular lesion [5].

In conclusion, our case represents the only report of a JF schwannoma with central flow voids on MRI. Though this appearance has been traditionally ascribed to paragangliomas, schwannoma should also be considered in JF lesions with a “salt & pepper” appearance on MRI. Ultimately, the pattern of tumor expansion may provide important insights in the imaging diagnosis.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Yousem D.M., Grossman R.I. 3rd ed. Mosby; Philadelphia, PA: 2010. Neuroradiology: The Requisites. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eldevik O.P., Gabrielsen T.O., Jacobsen E.A. Imaging findings in schwannomas of the jugular foramen. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:1139–1144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caldemeyer K.S., Mathews V.P., Azzarelli B., Smith R.R. The jugular foramen: a review of anatomy, masses, and imaging characteristics. Radiographics. 1997;17:1123–1139. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.17.5.9308106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogl T.J., Bisdas S. Differential diagnosis of jugular foramen lesions. Skull Base. 2009;19:3–16. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1103121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao A.B., Koeller K.K., Adair C.F. From the archives of the AFIP. Paragangliomas of the head and neck: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. Radiographics. 1999;19:1605–1632. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.6.g99no251605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramina R., Maniglia J.J., Fernandes Y.B. Jugular foramen tumors: diagnosis and treatment. Neurosurg Focus. 2004;17:E5. doi: 10.3171/foc.2004.17.2.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsen W.L., Dillon W.P., Kelly W.M., Norman D., Brant-Zawadzki M., Newton T.H. MR imaging of paragangliomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148:201–204. doi: 10.2214/ajr.148.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samii M., Babu R.P., Tatagiba M., Sepehrnia A. Surgical treatment of jugular foramen schwannomas. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:924–932. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.82.6.0924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King C.D., Long J.M., Hammon W.M. Early draining veins in acoustic neurinomas. Radiology. 1974;113:369–371. doi: 10.1148/113.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moscow N.P., Newton T.H. Angiographic features of hypervascular neurinomas of the head and neck. Radiology. 1975;114:635–640. doi: 10.1148/114.3.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonneville F., Cattin F., Czorny A., Bonneville J.F. Hypervascular intracisternal acoustic neuroma. J Neuroradiol. 2002;29:128–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamakami I., Kobayashi E., Iwadate Y., Saeki N., Yamaura A. Hypervascular vestibular schwannomas. Surg Neurol. 2002;57:105–112. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(01)00664-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato H., Kanematsu M., Mizuta K., Aoki M., Kuze B., Ohno T. “Flow-void” sign at MR imaging: a rare finding of extracranial head and neck schwannomas. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;31:703–705. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]