Abstract

Mobility, including migration and travel, influences risk of HIV. This study examined time trends and characteristics among mobile youth (15-24 years) in rural Uganda, and the relationship between mobility and risk factors for HIV. We used data from an annual household census and population-based cohort study in the Rakai district, Uganda. Data on in-migration and out-migration were collected among youth (15-24 years) from 43 communities from 1999-2011 (N=112,117 observations) and travel among youth residents from 2003-2008 (N=18,318 observations). Migration and travel were more common among young women than young men. One in five youth reported out-migration. Over time, out-migration increased among youth and in-migration remained largely stable. Primary reasons for migration included work, living with friends or family, and marriage. Recent travel within Uganda was common and increased slightly over time in teen women (15-19 years old), and young adult men and women (20-24 years old). Mobile youth were more likely to report HIV risk behaviours including: alcohol use, sexual experience, multiple partners, and inconsistent condom use. Our findings suggest that among rural Ugandan youth, mobility is increasingly common and associated with HIV risk factors. Knowledge of patterns and characteristics of a young, high-risk mobile population has important implications for HIV interventions.

Keywords: Migration, mobility, youth, Uganda, sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

Mobility, including migration and travel, influences health, including risk of HIV (Barongo et al., 1992; Evans, 1987; Gushulak & MacPherson, 2004; Lurie et al., 2003; Quinn, 1994). Previous research in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has indicated that adults who migrate or travel are at increased risk of acquiring HIV compared to their non-mobile counterparts (Lurie et al., 2003; Serwadda et al., 1992). Mobility is common for youth (15-24 years old) in SSA and connected to life transitions that can also influence HIV risk. Youth in SSA remain highly vulnerable to HIV, despite ongoing prevention and treatment efforts. Our study explores two aspects of mobility – migration (i.e. change in residence) and travel (i.e. short-term mobility) – and behavioural risk factors for HIV among youth in rural Uganda (Santelli et al., 2013).

Youth mobility

Children and youth frequently migrate (Camlin, Snow, & Hosegood, 2013; Van Blerk & Ansell, 2006; Young, 2004) and are mobile (Camlin et al., 2013; Porter, Blaufuss, & Owusu Acheampong, 2007) either as part of their family's mobility or independently. The experience of mobility and the subsequent adaptation to new environments are key elements of many young people's lives in Africa, and are often linked to education and employment (Adepoju, 2000; Bell, 1980; Bryceson, Mbara, & Maunder, 2003; Gough, 2008; Porter et al., 2007; Van Blerk & Ansell, 2006), youth identity formation (Langevang & Gough, 2009), gaining a respectable position in their family and society (Laoire, Carpena-Méndez, Tyrrell, & White, 2010; Thorsen, 2006), and marital formation or transitions, particularly among women (Boerma et al., 2002; Camlin, Kwena, Dworkin, Cohen, & Bukusi, 2014; Ntozi, 1997). Although the phenomenon of youth mobility has been recognized, the context in which this occurs and patterns over time are less understood.

Migration and mobility patterns in SSA are shifting from the traditional dominance of labor migration to the emergence of increasingly more diverse forms (Adepoju, 2000; Bell, 1980; Coffee et al., 2005; Hunt, 1989). Concurrently, in Uganda, diversification of livelihood has grown substantially in recent years, particularly among youth, and in response to a fluctuating economic environment that has persisted despite the country's growth in both population and GDP (Langevang, Namatovu, & Dawa, 2012; Pilgaard Kristensen & Birch-Thomsen, 2013; UBOS, 2014; World Bank, 2015). Participation in non-agricultural livelihood activities – including those within entrepreneurial, commercial and service sectors – has flourished, and is considered key to the country's future economic progress (Bryceson et al., 2003; Langevang et al., 2012; Potts, 2006, 2013; Smith, Gordon, Meadows, & Zwick, 2001; World Bank, 2009, 2013). These activities may inherently require migration or travel away from home. Agriculture remains a prominent source of employment in Uganda – accounting for a third of all workers and more than half of youth workers (UBOS, 2014; World Bank, 2009) – and can also entail mobility, as workers may travel or seasonally migrate to other agricultural areas (Bahiigwa, Rigby, & Woodhouse, 2005; Dolan, 2004; Ellis, 1998).

Mobility and HIV in Africa

Rural-urban labor migration patterns have been implicated in the rapid spread of HIV in Uganda (Quinn, 1994). Evidence from several African countries has demonstrated an increased risk for HIV infection among migrant populations and their partners (Bärnighausen, Hosegood, Timaeus, & Newell, 2007; Camlin et al., 2010; Lurie et al., 2003; Nunn, Wagner, Kamali, Kengeya-Kayondo, & Mulder, 1995; Zuma, Gouws, Williams, & Lurie, 2003). Increased geographic connectedness may allow for contact between epidemics and permit the disease to spread from regions of higher prevalence to those of lower prevalence (Boerma et al., 2002; Deane, Parkhurst, & Johnston, 2010; Nyanzi, Nyanzi, Kalina, & Pool, 2004). Migration (Blum, 2007; Evans, 1987; Lurie et al., 2003; Quinn, 1994; Van Blerk & Ansell, 2006) and movement (Bell, 1980) have also been described as a cause of social and educational disruption, disorientation, isolation, blurred identity, and disruption of sexual networks, which can influence HIV risk. Such factors may be particularly important in younger mobile populations.

In turn, HIV can have an impact on migration and mobility. Previous research in SSA has found that HIV-positive individuals are more likely to migrate than those who are HIV-negative (Anglewicz, 2012; Urassa et al., 2001; Wawer et al., 1997). This can be related to perceived stigma or discrimination in local communities, as well as access to HIV treatment and care. In addition, HIV can indirectly impact mobility via marital dissolution, which is associated with HIV and can result in migration for either spouse (Anglewicz, 2012). The familial burden of HIV may directly influence mobility among youth (Camlin et al., 2013; Gough, 2008; Van Blerk & Ansell, 2006). Studies have found that children and young adults move following the sickness or death of parents, resulting in the dissolution of the household. Migration may also be employed by families as a coping mechanism – they may send youth to work, to care for sick relatives, or to live with other family members or foster parents (Robson, Ansell, Huber, Gould, & van Blerk, 2006; Van Blerk & Ansell, 2006).

Our study explored mobility among youth over time, and characteristics of mobile youth including patterns of behavioural risk factors for HIV, in Rakai district, southeastern Uganda. Rakai has a history of a generalized HIV epidemic (Hunter, 2005; Serwadda et al., 1985). The area is traversed by major roads that carry traffic between countries such as Tanzania, Rwanda and, Kenya (Wawer et al., 1991), and improvements to the road networks within and around Rakai have facilitated transport-related HIV-risk activities (Smith et al., 2001). A recent longitudinal study in Rakai demonstrated substantial risk of new infection among youth (15-24 years) (Santelli et al., 2013). The incidence of HIV in this study was greater among young women (14.1 per 1,000 person-years) than young men (8.27 per 1,000 person-years). Building on this analysis, our study examines mobility patterns and behavioural risk factors for HIV among mobile young men and women in Rakai in an effort to add to the literature on youth mobility and HIV risk in SSA.

Methods

Data collection and sample

We examined characteristics of and trends in migration and travel among youth (15-24 years) participating in the Rakai Community Cohort Study (RCCS) between March 1999 and June 2011. The RCCS is a population-based, open cohort of residents from 43 secondary road trading centers and main road towns in Rakai. Communities in RCCS are enumerated in a census and surveyed approximately annually. Each administration of the census and survey is called a ‘round’; this analysis covers rounds 6-14. The census is administered in every household in the RCCS catchment area. The key census respondent is the head of the household. The census documents each household member by age, gender, and relationship to the head, and includes detailed information on any in- or out-migration (i.e. the type of movement, the reasons for moving, and the location of origin or destination) that occurred since the last census. Information from the census was used for our migration analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Time frame for trends analyses

Household members are considered eligible to participate in the RCCS survey based on age (15-49 years), residency of at least six months, and willingness to provide written informed consent. The survey collects socio-demographic, biological, and behavioural data from all participants. RCCS surveys are administered in a private face-to-face interview by trained same-sex interviewers. Survey participants are also asked to provide blood samples for HIV and STI testing. The RCCS achieves over 85% coverage of all residents, and 99% of consenting participants complete the entire survey. Information from the cohort study was used for our travel analysis (Figure 1).

A total of 112,117 youth (15-24 years) observations were eligible for the analysis of migration, based on information in the annual household census between rounds 6 and 14 (1999-2011). Of these, a total of 18,318 observations for youth were eligible for the travel analysis, based on participation in the RCCS survey during rounds 9-12 (2003-2008).

Description of variables

Our study measured mobility using data on migration and travel, an approach consistent with the literature (Aggleton, Bell, & Kelly-Hanku, 2014; Cassels, Manhart, Jenness, & Morris, 2013; Goldenberg, Strathdee, Perez-Rosales, & Sued, 2012). Data were collected via direct, self/proxy-reported measures. Some RCCS survey questions varied by RCCS round, including those on travel.

Migration was measured as a change in residence, and was designated as within, into, or out of the RCCS catchment area, also consistent with previous research in SSA (Camlin et al., 2010; Camlin et al., 2014). Variables obtained from the census were used to measure migration. In-migrants were defined as youth participants who had moved into their current community since the last round, either from outside the RCCS catchment area or from another community within the area. Out-migrants were defined as youth participants who had been enumerated in the census previously and who were reported as having migrated out of their community by the head of household. Any participants who reported circular migration or migration within their community were excluded from these analyses. The out-migration analysis was restricted to those individuals who had at least one prior round of participation in the census, as this is a requirement for being considered an out-migrant. Variables measuring reason for migration and place of origin or destination were used to further characterize the migrating population. Examples of reason for movement included ‘newly married’, ‘work’, and ‘education’; places of origin or destination included both urban and rural locations (i.e. ‘inside study area’, Kampala, and ‘other part of Uganda’).

Travel was defined as travel outside of the district (Rakai) but within the country (Uganda) within the 12 months prior to the time of interview. Participants were asked about travel within the last year in the RCCS survey during rounds 9 through 12 (2003-2008). Though other types of travel may be important, preliminary analyses demonstrated that travel within the district was nearly ubiquitous (98.0% among young men; 86.1% among young women) and travel outside of Uganda fairly infrequent (6.1% among young men; 2.3% among young women). Additionally, the number of youth who reported no travel (n=648 obs.) or only travel outside of Uganda (n=402 obs.) were comparatively small and demographically dissimilar from those who reported local travel. Therefore, to examine a representative sample of travelers, we restricted the descriptive and trends analyses of travelers to only those youth who had reported travel outside of Rakai district, but within Uganda, in the previous year during survey rounds 9-12.

Data to describe the demographic and behavioural characteristics of youth were obtained from the census and RCCS survey. Variables were selected based on a recent study of risk and protective factors for HIV acquisition among youth in Rakai (Santelli et al., 2013). Demographic characteristics included gender, age category (15-19 years vs. 20-24 years), area of residence (secondary road trading village vs. main road town), marital status, and highest level of educational attainment. Behavioural risk factors included alcohol use in the past 30 days, being sexual experienced, number of sexual partners in the past year, sexual concurrency at the time of interview, and condom use in the past year (never/inconsistently vs. always). Some demographic characteristics (i.e. marital status, educational attainment) and all behavioural HIV risk factors were only assessed in the RCCS survey, and thus analyses of these variables among migrants were restricted to in-migrants who had participated in the RCCS survey, and were not available to out-migrants. All analyses of educational attainment were restricted to only 20-24 year old youth, as younger participants might be progressing through school and thus level of education is not an indicator of final educational attainment. Analyses of multiple sexual partnerships, sexual concurrency, and condom use were restricted to youth who had reported being sexually experienced.

Analyses

Overall prevalence of in- and out-migration was estimated as proportions of the enumerated observations among youth in study rounds 6-14. The prevalence of travel in the previous year was estimated as proportions of the surveyed observations among youth in study rounds 9-12.

The distributions of demographic characteristics were compared between mobile youth and their non-mobile counterparts. For these comparative analyses, ‘non-migrants’ were defined as those who were not reported as having in- or out-migrated, or died, within the previous year on the census. ‘Non-travelers’ were defined as those who reportedly remained within Rakai district during the previous year. By definition, “non-travelers” excluded those who reported travel outside of Rakai district, but within Uganda, and those who reported travel outside of Uganda. The statistical significance of demographic differences between mobile and non-mobile groups was determined using cross-tabulations and the Pearson chi-square test.

Trends in in- and out-migration and travel were analyzed over time as designated by survey rounds, and according to gender and age group. Statistical significance of migration and travel trends were calculated using logistic regression, adjusted for single year of age.

Migration reason and place of origin/destination were estimated as proportions of the observations among in- and out-migrants, and examined according to age and gender. To determine if there were significant differences in reasons for migrating and locations of origin/destination between age groups, Pearson chi-square tests were conducted among male and female in- and out-migrants for each designated reason or location, with an alpha set at 0.05.

Lastly, we examined the prevalence of behavioural risk factors by in-migration and travel status using multivariate Poisson regression with robust standard errors. Covariates were informed by the analyses and included age, area of residence, marital status, educational attainment, and survey round. We reported the adjusted prevalence ratio and associated p-value.

Ethics

Approval for the current analysis, and for the RCCS and Rakai Youth Projects, was obtained from IRBs at Columbia University Medical Center, the Committee on Human Research at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and the Western Institutional Review Board, as well as the Uganda Virus Research Institute's Science and Ethics Committee and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology.

Results

Study populations

The sample of youth (aged 15-24 years) eligible for the migration analysis were those who were enumerated in the census during rounds 6-14 (n=112,117 obs.) The sample eligible for the travel analysis included youth who participated in the RCCS survey between rounds 9 and 12 (n=18,318 obs.)

Migration

Out-migration

Among Rakai youth, the prevalence of out-migration was 22.0% among young women and 17.7% among young men. The distribution of demographic characteristics among migrants and non-migrants are described in Table 1. Out-migrants were significantly more likely to be women and to live in main road towns, compared to non-migrants. Among male out-migrants, a significantly greater proportion were young adults (20-24 years) than among non-migrants; a statistically significant age difference was not seen between female out- and non-migrants.

Table 1.

Distribution of demographic characteristics of out-, in-, and non-migrants, Rakai Uganda, 1999-2011

| NON-MIGRANTS (no. obs. = 64,729) | OUT-MIGRANTS (no. obs. = 20,734) | IN-MIGRANTS (no. obs. = 16,910) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. obs. (%) | No. obs. (%) | No. obs. (%) | ||||

| Male | 31,315 (48.4%) | 8,112 (39.1%)1 | 5,405 (32.0%)1 | |||

| Female | 33,414 (51.6%) | 12,622 (60.9%)1 | 11,505 (68.0%)1 | |||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Age | ||||||

| 15-19 years | 19,473 (62.2%) | 18,352 (54.9%) | 4,544 (56.0%)1 | 7,034 (55.7%) | 2,357 (43.6%)1 | 5,498 (47.8%)1 |

| 20-24 years | 11,842 (37.8%) | 15,062 (45.1%) | 3,568 (44.0%)1 | 5,588 (44.3%) | 3,048 (56.4%)1 | 6,007 (52.2%)1 |

| Area of residence | ||||||

| Rural secondary road village | 25,653 (81.9%) | 26,916 (80.6%) | 6,281 (77.4%)1 | 9,458 (74.9%)1 | 3,973 (73.5%)1 | 8,328 (72.4%)1 |

| Main road town | 5,662 (18.1%) | 6,498 (19.5%) | 1,831 (22.6%)1 | 3,164 (25.1%)1 | 1,432 (26.5%)1 | 3,177 (27.6%)1 |

| Marital status2 | ||||||

| Never married | 12,761 (76.8%) | 8,693 (42.3%) | - | - | 1,710 (72.7%)1 | 1,682 (26.9%)1 |

| Currently married | 3,538 (21.3%) | 11,062 (53.8%) | - | - | 580 (24.7%)1 | 4,132 (66.1%)1 |

| Formerly married | 315 (1.9%) | 811 (3.9%) | - | - | 61 (2.6%)1 | 441 (7.1%)1 |

| Educational attainment (only 20-24 year old youth)2 | ||||||

| No schooling | 245 (3.1%) | 534 (4.6%) | - | - | 52 (3.8%)1 | 150 (4.5%)1 |

| Primary schooling | 5,204 (65.2%) | 7,354 (63.0%) | - | - | 778 (56.5%)1 | 1,707 (51.4%)1 |

| Secondary schooling | 2,421 (30.3%) | 3,717 (31.9%) | - | - | 488 (35.4%)1 | 1,395 (42.0%)1 |

| Tertiary schooling | 107 (1.3%) | 63 (0.5%) | - | - | 60 (4.4%)1 | 67 (2.0%)1 |

Note:

p < 0.001; p-values indicate the statistical significance of the differences between non-migrant and migrant groups, across given demographic characteristics.

Data on marital status and educational attainment were collected in the RCCS survey. Of all youth migrants, only those in-migrants who participated in the survey (n=2,353 male obs.; n=6,256 female obs.) were eligible for analyses of these two characteristics.

Between 2001 and 2011, out-migration significantly increased among all youth aged 15-24 years (Figure 2). Over time, and especially among women, teenaged youth (15-19 year olds) showed greater proportions of out-migration than young adults.

Figure 2.

Out-migration over time among youth in Rakai, 2000-2011

In-migration

Overall, 10.8% of young men and 18.4% of young women in-migrated during the period of this analysis. In-migrants were significantly more likely to be women, to be young adults, and to live in main road towns, compared to non-migrants (Table 1). Statistically significant differences in marital status and educational attainment between in- and non-migrants were seen among all youth.

Trends in in-migration were generally stable between 1999 and 2011, though a slight statistically significant decrease was observed (Figure 3). Among young adult men and women, the prevalence of in-migration has shown an increasing trend since 2004 (round 10).

Figure 3.

In-migration over time among youth in Rakai, 1999-2011

Origin, destination and reason for in- and out-migration

‘Work’ and ‘living with friends or relatives’ were the most commonly reported reasons for movement among all migrants (Table 2). Migrating into Rakai for work was significantly more common among young adults, though this difference was not found for out-migrants. Out-migration to live with a friend or relative was significantly more common among teenaged men compared to young adults, but this was not seen among women. Migrating for a new marriage was reported by young women, particularly among in-migrants, and was significantly more prevalent among teenaged women compared to young adults. Female out-migrants also reported moving due to divorce or separation; this was significantly more prevalent among young adults. Among young men, starting a new household was a common reason for both in- and out-migration. Young adults were significantly more likely than teenagers to move for this reason. Migrating for educational purposes was not common, but was significantly more so among teenagers.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of travelers and non-travelers, Rakai Uganda, 1999-2011

| NON-TRAVELERS1 (no. obs. = 4,639) | TRAVELERS2 (no. obs. = 5,403) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. obs. (%) | No. obs. (%) | |||

| Male | 1,450 (31.2%) | 2,558 (47.3%)3 | ||

| Female | 3,189 (68.7%) | 2,845 (52.7%)3 | ||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Age | ||||

| 15-19 years | 1,067 (73.6%) | 1,712 (53.7%) | 1,383 (54.1%)3 | 1,462 (51.4%) |

| 20-24 years | 383 (26.4%) | 1,477 (46.3%) | 1,175 (45.9%)3 | 1,383 (48.6%) |

| Area of residence | ||||

| Rural secondary road village | 1,258 (86.8%) | 2,715 (85.1%) | 2,096 (81.9%)3 | 2,203 (77.4%)3 |

| Main road town | 192 (13.2%) | 474 (14.9%) | 462 (18.1%)3 | 642 (22.6%)3 |

| Marital status4 | ||||

| Never married | 1,266 (87.3%) | 1,246 (39.1%) | 2,027 (79.2%)3 | 1.436 (50.5%)3 |

| Currently married | 170 (11.7%) | 1,818 (57.0%) | 490 (19.2%)3 | 1.292 (45.4%)3 |

| Formerly married | 14 (1.0%) | 125 (3.9%) | 41 (1.6%)3 | 125 (4.4%)3 |

| Educational attainment (only 20-24 year old youth)4 | ||||

| No schooling | 19 (5.0%) | 79 (5.4%) | 31 (2.6%)3 | 43 (3.1%)3 |

| Primary schooling | 294 (76.9%) | 1,025 (69.5%) | 675 (57.4%)3 | 623 (45.1%)3 |

| Secondary schooling | 70 (18.3%) | 370 (25.1%) | 439 (37.4%)3 | 682 (49.3%)3 |

| Tertiary schooling | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.0%) | 30 (2.6%)3 | 34 (2.5%)3 |

Note:

Non-travelers defined as those who did not report travel outside Rakai, in Uganda, within the last year, among youth in the RCCS survey during rounds 9-12 (2003-2008). This group excludes those who reported travel outside of Uganda.

Travelers defined as those who reported travel outside Rakai, in Uganda, within the last year, among youth in the RCCS survey during rounds 9-12 (2003-2008).

p < 0.001; p-values indicate the statistical significance of the differences between non-travelers and travelers, across given demographic characteristics.

Data on marital status and educational attainment were collected in the RCCS survey. Of all youth migrants, only in-migrants who participated in the survey (n=2,353 male obs.; n=6,256 female obs.) were eligible for analyses of these two characteristics.

For all migrants, the most common origin or destination was within Rakai district but outside of the RCCS study area (Table 2). Out-migration to another part of Rakai district was significantly more prevalent among young adults compared to teenagers. Among female inmigrants, this was slightly but significantly more common among teenagers. A substantial proportion of out-migrants, and some in-migrants, were reported as having moved to or from the cities of Kampala or Masaka, or another part of Uganda. Among out-migrants, these urban destinations were reported by significantly more teenagers than young adults; similar differences were not found among in-migrants.

Travel

The prevalence of travel within the last year was 65.0% among young men and 47.2% among young women. Travelers were significantly more likely than non-travelers to be young women and to live in main road towns (Table 3). Among male travelers, a significantly greater proportion were young adults, compared to non-travelers. Differences in marital status and educational attainment between travelers and non-travelers were significant for all youth.

Table 3.

Migration reasons and places of origin/destination, Rakai Uganda, 1999-2011

| IN-MIGRANTS (no. of obs.=16,910) | OUT-MIGRANTS (no. of obs.=20,734) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age/Sex of migrant1 | Teen Men | YA Men | Teen Women | YA Women | Teen Men | YA Men | Teen Women | YA Women |

| Reason for migration | ||||||||

| Work | 31.3%2 | 51.3%2 | 14.5%2 | 28.9%2 | 58.5% | 56.3% | 27.8% | 27.2% |

| Living w/friends or relatives | 53.9%2 | 12.8%2 | 45.2%2 | 39.9%2 | 31.8%2 | 14.5%2 | 42.6%3 | 45.6%3 |

| Start new household | 9.1%2 | 33.7%2 | 1.2%2 | 4.4%2 | 5.6%2 | 26.3%2 | 0.8%2 | 3.9%2 |

| Newly married | 0.0%2 | 0.8%2 | 36.4%2 | 26.1%2 | 0.1% | 0.1% | 17.8%2 | 6.3%2 |

| Divorced/separated | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.1%2 | 1.1%2 | 7.8%2 | 16.3%2 |

| Education | 5.1%2 | 1.2%2 | 2.5%2 | 0.4%2 | 3.8%2 | 1.4%2 | 3.1%2 | 0.6%2 |

| Other | 0.4%4 | 0.1%4 | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1%4 | 0.3%4 | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Place of origin or destination | ||||||||

| Within study area | 3.2%3 | 4.7%3 | 4.6%2 | 8.9%2 | 0.2% | 0.5% | 0.2%2 | 0.8%2 |

| Within Rakai district, outside study area | 72.6% | 72.5% | 69.9%2 | 64.2%2 | 32.4%2 | 50.2%2 | 42.4%2 | 56.4%2 |

| Outside Rakai district | ||||||||

| Masaka | 9.5% | 8.7% | 12.0% | 11.8% | 12.0%3 | 9.6%3 | 14.3%2 | 11.7%2 |

| Kampala | 5.2% | 5.1% | 4.6%4 | 5.5%4 | 46.2%2 | 30.7%2 | 35.0%2 | 23.3%2 |

| Other part of Uganda | 8.1% | 8.0% | 6.9% | 7.7% | 7.8% | 7.1% | 6.9% | 6.9% |

| Other country | 1.3% | 1.1% | 2.0% | 1.9% | 1.4% | 2.0% | 1.3% | 0.9% |

Note:

'Teen' indicates teenaged (15-19 years old); 'YA' indicates young adult (20-24 years old).

p < 0.001

p < 0.01

p < 0.05

All p-values represent the statistical significance of the difference between young adult (20-24 years old) migrants and their younger counterparts (teenagers, 15-19 years) in reasons for migration, and places of origin/destination, within each gender.

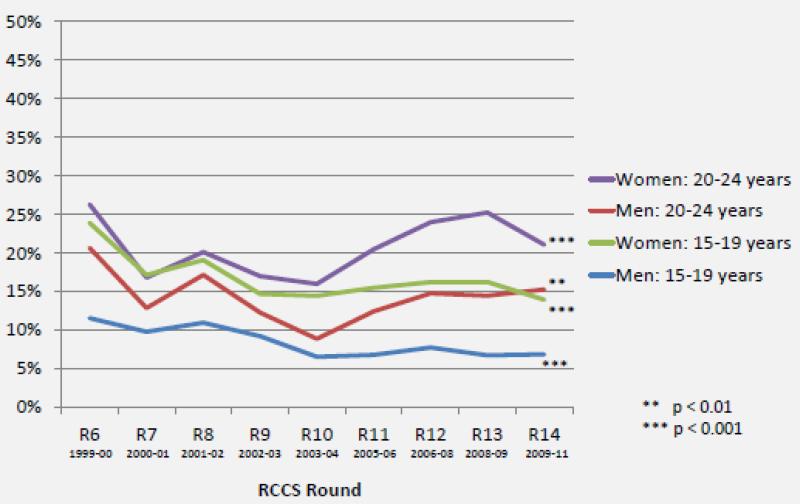

Travel showed a gradually increasing trend between 2003 and 2008 (Figure 4). Differences in the prevalence of travel between young men and young women, as well as those between older youth and younger youth, remained largely consistent over time.

Figure 4.

Travel outside of Rakai, in Uganda, within the last year among youth in Rakai, 2003-2008

Prevalence of behavioural risk factors by migration and travel status

Among young men (Table 4a), in-migration was significantly associated with the use of alcohol in the last 30 days, ever having a sexual experience, multiple (i.e. two or more) sexual partnerships, and inconsistent condom use, after controlling for all demographic variables. Similarly, young men who were travelers reported significantly greater proportions of behavioural characteristics than non-travelers, including alcohol use, sexual experience, concurrency, and multiple partnerships. However, male travelers also reported significantly more consistent condom use than non-travelers.

Table 4a.

Prevalence of behavioural characteristics by mobility status among young men, Rakai Uganda, 1999-2011

| In-migration1 | Travel2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-migrants | Non-migrants | Adjusted PRR | p-value3 | Travelers | Non-travelers | Adjusted PRR | p-value3 | |

| Drank alcohol in last 30 days | 38.0% | 33.1% | 1.14 | 0.001 | 23.9% | 18.5% | 1.12 | 0.086 |

| Ever had sex | 83.4% | 73.6% | 1.08 | <0.001 | 75.2% | 54.7% | 1.23 | <0.001 |

| Two or more sexual partners in last year4 | 44.8% | 38.5% | 1.15 | <0.001 | 40.7% | 30.8% | 1.30 | <0.001 |

| Concurrent partnership at time of interview4 | 14.5% | 16.2% | 0.89 | 0.056 | 16.8% | 10.2% | 1.61 | <0.001 |

| Consistent condom use in last year4 | 22.0% | 28.9% | 0.76 | <0.001 | 30.6% | 22.5% | 1.30 | <0.001 |

Note:

Analysis among in-migrants restricted to those who participated in RCCS survey (n=8,609).

Travel defined travel outside Rakai, in Uganda, within the last year among youth in the RCCS survey during rounds 9-12 (2003-2008).

Adjusted for age, area of residence, marital status, and educational attainment.

Among sexually experienced respondents only.

Female in-migrants (Table 4b) reported significantly more alcohol use in the last 30 days, sexual experience, multiple partnerships, concurrent partnerships, and inconsistent condom use than female non-migrants, after controlling for demographic variables. Young women who were travelers also demonstrated greater prevalence than non-travelers of alcohol use, sexual experience, and multiple partnerships. As among men, female travelers reported significantly more consistent condom use than non-travelers.

Table 4b.

Behavioural characteristics by mobility status among young women, Rakai Uganda, 1999-2011

| In-migration1 | Travel2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-migrants | Non-migrants | Adjusted PRR | p-value3 | Travelers | Non-travelers | Adjusted PRR | p-value3 | |

| Drank alcohol in last 30 days | 28.2% | 21.8% | 1.26 | <0.001 | 18.0% | 14.5% | 1.28 | <0.001 |

| Ever had sex | 94.5% | 82.2% | 1.10 | <0.001 | 82.1% | 80.3% | 1.05 | <0.001 |

| Two or more sexual partners in last year4 | 13.3% | 5.1% | 2.52 | <0.001 | 10.6% | 6.6% | 1.75 | <0.001 |

| Concurrent partnership at time of interview4 | 2.3% | 1.8% | 1.24 | 0.039 | 2.5% | 1.6% | 1.32 | 0.192 |

| Consistent condom use in last year4 | 8.7% | 12.5% | 0.87 | 0.001 | 17.3% | 8.9% | 1.21 | 0.005 |

Note:

Analysis among in-migrants restricted to those who participated in RCCS survey (n=8,609).

Travel defined travel outside Rakai, in Uganda, within the last year among youth in the RCCS survey during rounds 9-12 (2003-2008).

Adjusted for age, area of residence, marital status, and educational attainment.

Among sexually experienced respondents only.

Discussion

In this study we attempted to delineate the context and patterns of youth mobility within a generalized high HIV epidemic. Mobility is common among youth in Rakai -- approximately one in five youth were reported as having migrating out of the RCCS study area, and slightly fewer reported recent migration into the study area. Over half of youth participants reported having traveled outside Rakai but within Uganda during the year prior to the survey, similar to previous research describing high rates of travel among youth in SSA (Coffee et al., 2005). Out-migration and travel have shown significant increases over time among 15-24 year old youth in this sample. In our study, commonly reported reasons for migration -- including moving to live with a friend or relative, marriage, and work -- align with literature describing youth migration and mobility that takes place amidst changes in economic or familial structures (Adepoju, 2000; Boerma et al., 2002; Gough, 2008).

The demographic profiles of migrants and travelers in this study are similar to what has been reported in previous research in SSA. The greater proportion of women among migrants compared to non-migrants mirrors the increasing presence of migrating young women in developing countries, or the ‘feminization of migration’ (Camlin et al., 2013) that has been noted in recent literature (Booysen, 2006; Camlin et al., 2010; Camlin et al., 2014; Temin, Montgomery, Engebretsen, & Barker, 2013). Part of this pattern may be explained by livelihood diversification -- women may migrate seeking economic independence, and begin to share more income-earning and other familial responsibilities with their male partners (Adepoju, 2000; Bryceson, 2002; Camlin et al., 2014; Temin et al., 2013). Work-related migration was common among young women and young men in Rakai, particularly for older youth.

Gender differences within the travel analysis were not as distinct. Young women were less likely to travel outside of Rakai district, possibly due to stronger ties to home and family responsibilities common among women in SSA (Dolan, 2004; Ellis, 1998). In Uganda and other countries in SSA, women's jobs often lie more within informal sectors, and may be less profitable and closer to home than men's (Bryceson, 2002; Dolan, 2004; Lurie, Harrison, Wilkinson, & Abdool Karim, 1997; Pilgaard Kristensen & Birch-Thomsen, 2013; UBOS, 2014). At the same time, many women did report travel, constituting more than half of the traveler population. This may reflect the necessity for travel that accompanies some informal work such as trade or sex work (Boerma et al., 2002; Camlin et al., 2014; Nyanzi, Nyanzi, Wolff, & Whiteworth, 2005).

Our results among male migrants and travelers align with literature describing largely unmarried mobile populations (Boerma et al., 2002; Coffee et al., 2005; Nunn et al., 1995). Among young women, however, patterns demonstrate an important relationship between mobility and marriage, with implications for HIV risk. Young women who migrated were more often married than non-migrants. Marriage was reported as a primary motivation for women's migration, particularly among teenagers, as has been found previously in SSA (Anglewicz, 2012; Boerma et al., 2002). Thus, it appears that women's migration is strongly tied to marriage, and to a greater extent than men's. In Uganda, women's lack of access to land or assets, and the associated economic difficulties, may help to maintain financial dependency on men (Dolan, 2004) and facilitate both marriage- and employment-related migration (Anglewicz, 2012). Among female travelers, however, rates of marriage were lower than among non-travelers, perhaps indicating fewer restrictions on mobility among those women who are not married. The link between women's migration and marriage extends to marital dissolution; in our study, nearly a fifth of female out-migrants reported moving due to divorce or separation, and inmigrants were significantly more likely to be formerly married than non-migrants. This aligns with previous research in SSA describing migration and mobility following divorce/separation (Boerma et al., 2002) or widowhood (Ntozi, 1997) among women, and less so among men. Importantly, mobility due to marital dissolution has been linked to HIV status, wherein those who migrate for this reason are more likely to be HIV-positive (Anglewicz, 2012). Thus, the relationship between mobility and marriage among young women is critical, and may extend across various phases of the life course.

Other reported reasons for migration included education, and moving to live with a friend or relative. The small number of migrants who reported moving for education contrasts with what has been found previously among youth in Uganda, in which education accounts for the majority of migration (Pilgaard Kristensen & Birch-Thomsen, 2013). This may be due to the close proximity of schools (UBOS, 2014) and thus a heavier reliance on daily mobility rather than migration (Bryceson et al., 2003). Among young adults, those who were migrants or travelers reported higher levels of educational attainment compared with non-mobile youth; this has been previously found in SSA (Anglewicz, 2012) and may reflect more diverse livelihood-seeking or greater economic capital among those with more education. Migration to live with a friend or relative was highly common, particularly among teenaged youth; this movement may occur as a means of sharing caretaking responsibilities for a sick family member (Gough, 2008), or in response to a parental illness or death, and resulting household dissolution (Urassa et al., 2001). It may also include movement to live with a friend or relative who is closer in proximity to work or educational opportunities.

Importantly, several behavioural risk factors for HIV were more commonly reported by mobile youth compared to non-mobile peers. The relationships remained significant after controlling for demographic characteristics, such as age and marital status, that have been previously associated with HIV incidence among youth in Rakai (Santelli et al., 2013). These patterns delineate mobile youth in Rakai as a group at especially high risk of HIV. Previous research has demonstrated elevated HIV risk and risk behaviours among mobile populations, though largely among adults (Anglewicz, 2012; Bärnighausen et al., 2007; Brockerhoff & Biddlecom, 1999; Goldenberg et al., 2012; Kwena, Camlin, Shisanya, Mwanzo, & Bukusi, 2013; Tiruneh, Wasie, & Gonzalez, 2015; Zuma et al., 2003). Female migrants have been described as a particularly vulnerable group (Brockerhoff & Biddlecom, 1999; Camlin et al., 2014; Temin et al., 2013). While a full exploration of mobility and HIV among youth in Uganda is beyond the scope of this paper, it is clear that the relationship between mobility and HIV risk among youth is dynamic and complex, and warrants further attention. In our study, differences in the presence of behavioural risk factors for HIV across groups of migrants and travelers presented interesting distinctions. For instance, male and female in-migrants were more likely to report inconsistent condom use than non-migrants, but the opposite relationship was seen between travelers and non-travelers. Previous research has found high rates of inconsistent condom use among migrants in Africa (Brummer, 2002; Tiruneh et al., 2015) yet concurrently, migrant populations have been described as more knowledgeable about and perceptive of HIV risk than non-migrants (Brockerhoff & Biddlecom, 1999). It is possible that travelers in our study may have been more highly exposed to HIV prevention messaging and behaviours in their home communities, compared to migrants, and perceived themselves at high risk, which may influence condom use. This may have been especially true for those who reported maintaining multiple or concurrent sexual partnerships. At the same time, HIV-positive individuals have been described as more mobile than HIV-negative individuals (Anglewicz, 2012), which may also influence HIV risk behaviour. Thus, the relationship between mobility and HIV risk is multifaceted and not necessarily unidirectional; the unique nature of this relationship necessitates further research in this area, particularly among high-risk populations such as youth.

A confluence of various factors may influence the relationship between mobility and behavioural risk factors for HIV, including those related to the individual (e.g. gender, marital status), the process of movement itself (e.g. separation from spouse), perception of HIV risk, and characteristics of the new social environment (e.g. social support network, income-earning opportunities) (Brockerhoff & Biddlecom, 1999). These factors intertwine and overlap to create unique risk profiles among mobile populations. Female migrants in our study, for example, were more likely to report sexual experience than non-migrants, but were also more likely to be married. While both marriage and migration may directly impact sexual experience and behaviour, the extent of each contribution is likely unique to the individual. Though the links between mobility and HIV risk behaviour in our study persisted despite the influence of factors such as age and marital status, the distinctive set of dynamics related to these processes among young men and women in Uganda warrants further understanding of the nature of these relationships.

Limitations

Census and survey variables were based on proxy/self-report, and therefore may be subject to bias. Survey variables in the RCCS were not included in every round and the specific wording of survey questions (i.e. time frame) also varied. Additionally, our study was limited to data derived from only a few questions within the RCCS census and survey, and therefore may not represent the full scope of mobility in the Ugandan context. However, given the large sample size and consistently high response rates in the RCCS census and survey, our results likely portray a fairly accurate picture of youth mobility in Rakai district. In addition, our study described the context of migration (i.e. reason for migration; place of origin/destination), as well as differences between mobile and non-mobile groups, and thus provides further characterization of mobile youth in Rakai. Although previous studies have described difficulties in measuring migration (Deane et al., 2010; Lurie et al., 1997), our study uses a consistent and reliable indicator of migration among our population over time. This study also utilized multivariate methods to determine the influence of mobility on HIV risk factors, controlling for various demographic factors, thereby reducing the risk of confounding or biases in these relationships.

Implications

Our study provides evidence of the unique and heterogeneous nature of young, mobile populations in SSA. Understanding patterns and characteristics of mobile youth can inform future HIV prevention and treatment interventions in this area. Such interventions should address the unique HIV risks of mobile youth by using an integrated, multi-level approach to acknowledge mobility and its associated risk as products of both the individual and the social context (Camlin et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014; Organista, Carrillo, & Ayala, 2004). As suggested by Deane et al. (2010), future work in this area must ‘embrace a more targeted approach to enhance our understandings of the link between mobility and the spread of HIV... and to enable the design of new and more location-specific interventions to mitigate risk enhancement.’ Additionally, HIV risk among mobile populations may not be due to the movement itself, but rather to the unique set of conditions and behaviours that accompany mobility and adaptation to new environments (UNAIDS, 2001). In our study, mobile young men and women presented distinct risk profiles, and unique sets of characteristics and behaviours, highlighting the importance of considering context and individual heterogeneity when assessing HIV risk among mobile youth. Additional research in this area is critical to gaining a more complete understanding of the process of mobility for young people in Uganda and other parts of SSA, and the means by which HIV risk is associated, in order to appropriately inform future programming.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research is supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development [grant number 5R01HD061092-05]; and a National Institutes of Health/National Institutes of Mental Health training grant for Z.R. Edelstein [grant number T32-MH19139].

References

- Adepoju A. Issues and recent trends in international migration in sub Saharan Africa. International Social Science Journal. 2000;52(165):383–394. [Google Scholar]

- Aggleton P, Bell SA, Kelly-Hanku A. ‘Mobile men with money’: HIV prevention and the erasure of difference. Global Public Health. 2014;9(3):257–270. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.889736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglewicz P. Migration, marital change, and HIV infection in Malawi. Demography. 2012;49(1):239–265. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0072-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahiigwa G, Rigby D, Woodhouse P. Right target, wrong mechanism? Agricultural modernization and poverty reduction in Uganda. World Development. 2005;33(3):481–496. [Google Scholar]

- Bärnighausen T, Hosegood V, Timaeus IM, Newell M-L. The socioeconomic determinants of HIV incidence: Evidence from a longitudinal, population-based study in rural South Africa. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 7):S29. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000300533.59483.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barongo LR, Borgdorff MW, Mosha FF, Nicoll A, Grosskurth H, Senkoro KP, Killewo JZ. The epidemiology of HIV-1 infection in urban areas, roadside settlements and rural villages in Mwanza Region, Tanzania. AIDS. 1992;6(12):1521–1528. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199212000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell M. Patterns of youth mobility in Uganda. Journal of Asian and African Studies. 1980;15(3-4):203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Blum RW. Youth in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;41(3):230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerma JT, Urassa M, Nnko S, Ng'weshemi J, Isingo R, Zaba B, Mwaluko G. Sociodemographic context of the AIDS epidemic in a rural area in Tanzania with a focus on people's mobility and marriage. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2002;78(suppl 1):i97–i105. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.suppl_1.i97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booysen F. Out-migration in the context of the HIV/AIDS epidemic: Evidence from the Free State province. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2006;32(04):603–631. [Google Scholar]

- Brockerhoff M, Biddlecom AE. Migration, sexual behavior and the risk of HIV in Kenya. International Migration Review. 1999:833–856. [Google Scholar]

- Brummer D. Labour migration and HIV/AIDS in southern Africa. International Organization for Migration Regional Office for Southern Africa. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Bryceson DF. The scramble in Africa: Reorienting rural livelihoods. World Development. 2002;30(5):725–739. [Google Scholar]

- Bryceson DF, Mbara TC, Maunder D. Livelihoods, daily mobility and poverty in sub-Saharan Africa. Transport Reviews. 2003;23(2):177–196. [Google Scholar]

- Camlin CS, Hosegood V, Newell M-L, McGrath N, Bärnighausen T, Snow RC. Gender, migration and HIV in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. PloS ONE. 2010;5(7):e11539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camlin CS, Kwena ZA, Dworkin SL, Cohen CR, Bukusi EA. ‘She mixes her business’: HIV transmission and acquisition risks among female migrants in western Kenya. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;102:146–156. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camlin CS, Snow RC, Hosegood V. Gendered patterns of migration in rural South Africa. Population, Space and Place. 2013;20(6):528–551. doi: 10.1002/psp.1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassels S, Manhart L, Jenness SM, Morris M. Short-term mobility and increased partnership concurrency among men in Zimbabwe. PloS ONE. 2013;8(6):e66342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffee MP, Garnett GP, Mlilo M, Voeten HA, Chandiwana S, Gregson S. Patterns of movement and risk of HIV infection in rural Zimbabwe. Journal of Infectious Disease. 2005;191(1):S159–S167. doi: 10.1086/425270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane KD, Parkhurst JO, Johnston D. Linking migration, mobility and HIV. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2010;15(12):1458–1463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan CS. ‘I sell my labour now’: Gender and livelihood diversification in Uganda. Canadian Journal of Development Studies. 2004;25(4):643–661. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis F. Household strategies and rural livelihood diversification. The Journal of Development Studies. 1998;35(1):1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Evans J. Introduction: Migration and Health. International Migration Review. 1987;21(3):v, xiv. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg SM, Strathdee SA, Perez-Rosales MD, Sued O. Mobility and HIV in Central America and Mexico: A critical review. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2012;14(1):48–64. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9505-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough KV. ‘Moving around’: The social and spatial mobility of youth in Lusaka. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography. 2008;90(3):243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Gushulak BD, MacPherson DW. Globalization of infectious diseases: The impact of migration. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2004;38(12):1742–1748. doi: 10.1086/421268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt CW. Migrant labor and sexually transmitted disease: AIDS in Africa. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1989:353–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter M. Cultural politics and masculinities: Multiple partners in historical perspective in KwaZulu Natal. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2005;7(4):389–403. doi: 10.1080/13691050412331293458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwena ZA, Camlin CS, Shisanya CA, Mwanzo I, Bukusi EA. Short-term mobility and the risk of HIV infection among married couples in the fishing communities along Lake Victoria, Kenya. PloS one. 2013;8(1):e54523. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langevang T, Gough KV. Surviving through movement: The mobility of urban youth in Ghana. Social & Cultural Geography. 2009;10(7):741–756. [Google Scholar]

- Langevang T, Namatovu R, Dawa S. Beyond necessity and opportunity entrepreneurship: Motivations and aspirations of young entrepreneurs in Uganda. International Development Planning Review. 2012;34(4):439–460. [Google Scholar]

- Laoire CN, Carpena-Méndez F, Tyrrell N, White A. Introduction: Childhood and migration—mobilities, homes and belongings. Childhood. 2010;17(2):155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Lin D, Wang B, Du H, Tam CC, Stanton B. Efficacy of theory-based HIV behavioral prevention among rural-to-urban migrants in China: A randomized controlled trial. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2014;26(4):296–316. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2014.26.4.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie M, Harrison A, Wilkinson D, Abdool Karim S. Circular migration and sexual networking in rural KwaZulu/Natal: Implications for the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. Health Transition Review. 1997;7(3):17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lurie MN, Williams BG, Zuma K, Mkaya-Mwamburi D, Garnett GP, Sturm AW, Karim SSA. The impact of migration on HIV-1 transmission in South Africa: A study of migrant and nonmigrant men and their partners. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2003;30(2):149–156. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200302000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ntozi JP. Widowhood, remarriage and migration during the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Uganda. Health Transition Review. 1997:125–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunn A, Wagner H-U, Kamali A, Kengeya-Kayondo JF, Mulder DW. Migration and HIV-1 seroprevalence in a rural Ugandan population. AIDS. 1995;9:503–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyanzi B, Nyanzi S, Wolff B, Whiteworth J. Money, men and markets: Economic and sexual empowerment of market women in southwestern Uganda. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2005;7(1):13–26. doi: 10.1080/13691050410001731099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyanzi S, Nyanzi B, Kalina B, Pool R. Mobility, sexual networks and exchange among bodabodamen in southwest Uganda. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2004;6(3):239–254. doi: 10.1080/13691050310001658208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organista KC, Carrillo H, Ayala G. HIV prevention with Mexican migrants: Review, critique, and recommendations. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;37:S227–S239. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000141250.08475.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilgaard Kristensen SB, Birch-Thomsen T. Should I stay or should I go? Rural youth employment in Uganda and Zambia. International Development Planning Review. 2013;35(2):175–201. [Google Scholar]

- Porter G, Blaufuss K, Owusu Acheampong F. Youth, mobility and rural livelihoods in sub-Saharan Africa: perspectives from Ghana and Nigeria. Africa Insight. 2007;37(3):420–431. [Google Scholar]

- Potts D. ‘All my hopes and dreams are shattered’: Urbanization and migrancy in an imploding African economy–the case of Zimbabwe. Geoforum. 2006;37(4):536–551. [Google Scholar]

- Potts D. Migrating Out of Poverty Research Programme Consortium. Brighton, U.K.: 2013. Rural-urban and urban-rural migration flows as indicators of economic opportunity in sub-Saharan Africa: What do the data tell us? Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn TC. Population migration and the spread of types 1 and 2 human immunodeficiency viruses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1994;91(7):2407–2414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson E, Ansell N, Huber U, Gould W, van Blerk L. Young caregivers in the context of the HIV/AIDS pandemic in sub Saharan Africa. Population, Space and Place. 2006;12(2):93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Santelli JS, Edelstein ZR, Mathur S, Wei Y, Zhang W, Orr MG, Higgins JA, Nalugoda F, Gray RH, Wawer MJ. Behavioral, biological, and demographic risk and protective factors for new HIV infections among youth in Rakai, Uganda. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2013;63(3):393–400. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182926795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serwadda D, Sewankambo N, Carswell J, Bayley A, Tedder R, Weiss R, Mugerwa RD, Lwegaba A, Kirya GB, Downing RG. Slim disease: A new disease in Uganda and its association with HTLV-III infection. The Lancet. 1985;326(8460):849–852. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(85)90122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serwadda D, Wawer MJ, Musgrave SD, Sewankambo NK, Kaplan JE, Gray RH. HIV risk factors in three geographic strata of rural Rakai District, Uganda. AIDS. 1992;6(9):983–990. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199209000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DR, Gordon A, Meadows K, Zwick K. Livelihood diversification in Uganda: Patterns and determinants of change across two rural districts. Food Policy. 2001;26(4):421–435. [Google Scholar]

- Temin M, Montgomery MR, Engebretsen S, Barker KM. Girls on the move: Adolescent girls & migration in the developing world. In: Population Council, editor. Girls Count. Population Council; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thorsen D. Child migrants in transit: Strategies to assert new identities in rural Burkina Faso. In: Christiansen C, Utas M, Vigh HE, editors. Navigating youth, generating adulthood: Social becoming in an African context. Nordiska Afrikainstitutet; Uppsala: 2006. pp. 88–114. [Google Scholar]

- Tiruneh K, Wasie B, Gonzalez H. Sexual behavior and vulnerability to HIV infection among seasonal migrant laborers in Metema district, northwest Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):122. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1468-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UBOS [Uganda Bureau of Statistics] Uganda National Household Survey 2012/2013. UBOS; Kampala, Uganda: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS . UNAIDS technical update: Population mobility and AIDS. UNAIDS; Geneva: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Urassa M, Boerma JT, Isingo R, Ngalula J, Ng’weshemi J, Mwaluko G, Zaba B. The impact of HIV/AIDS on mortality and household mobility in rural Tanzania. AIDS. 2001;15(15):2017–2023. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200110190-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Blerk L, Ansell N. Children's experiences of migration in Southern Africa: Moving in the wake of AIDS. Environment and Planning D–Society and Space. 2006;24(3):449–471. [Google Scholar]

- Wawer MJ, Serwadda D, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, Li C, Nalugoda F, Lutalo T, Konde-Lule JK. Trends in HIV-1 prevalence may not reflect trends in incidence in mature epidemics: Data from the Rakai population-based cohort, Uganda. AIDS. 1997;11(8):1023. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199708000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wawer MJ, Serwadda D, Musgrave SD, Konde-Lule JK, Musagara M, Sewankambo NK. Dynamics of spread of HIV-I infection in a rural district of Uganda. BMJ. 1991;303(6813):1303. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6813.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . Africa Development Indicators 2008/09. World Bank; Washington, DC: 2009. Youth and employment in Africa: The potential, the problem, the promise. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . Jobs: Key to prosperity – Main report, Uganda economic update. Vol. 2. World Bank; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Data - Uganda. 2015 Mar; 2015. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/country/uganda.

- Young L. Journeys to the street: the complex migration geographies of Ugandan street children. Geoforum. 2004;35(4):471–488. [Google Scholar]

- Zuma K, Gouws E, Williams B, Lurie M. Risk factors for HIV infection among women in Carletonville, South Africa: Migration, demography and sexually transmitted diseases. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2003;14(12):814–817. doi: 10.1258/095646203322556147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]