Abstract

Introduction

The purpose of the present study was to determine whether the abatacept autoinjector can be used by the intended population without patterns of preventable use errors, and is acceptable when assessed against key user needs.

Methods

Two independently conducted simulated-use studies, with no active drug administered, quantified use errors and evaluated the abatacept autoinjector and competitor devices on key attributes (comfort, control, ease of use, confidence of dose) and overall acceptability. Autoinjector preference was also assessed. Participants were patients with rheumatoid arthritis, caregivers, and healthcare professionals (HCPs). Participants were informed that a new rheumatoid arthritis autoinjector was being tested but were blinded to the intended drug and sponsor identity.

Results

In the formative (pre-validation) study (n = 54), two high-priority use errors occurred, both of which resulted from protocol non-compliance rather than mental confusion or physical limitations. In the summative (validation) study (n = 99), one high-priority use error occurred; this was deemed a simulated-use study artifact as participant behavior was guided by actual experience associated with the feel of drug delivery into the skin rather than by protocol, so no mitigation steps were considered necessary. Across user groups, average scores were consistently high for the pre-defined key attributes. Overall acceptability scores (7-point scale) were significantly higher for the abatacept versus competitor autoinjectors—formative study: patients 6.7 vs 5.2 (P = 0.0001), caregivers 7.0 vs 4.6 (P = 0.0093), HCPs 6.8 vs 5.1 (P = 0.0020); summative study: patients 6.5 vs 5.9 (P = 0.0404), caregivers 6.8 vs 5.8 (P = 0.0047), HCPs 6.8 vs 5.1 (P = 0.0002). The abatacept autoinjector was preferred to competitor devices: patients 85.7% vs 14.3% (P = 0.00002), caregivers 84.2% vs 15.8% (P = 0.00443), HCPs 95.0% vs 5.0% (P = 0.00004). Positive experiences with the abatacept autoinjector were attributed to the rubberized grip, device size, visualization of dose progression, button ergonomics, and ease of use.

Conclusion

The abatacept autoinjector demonstrated usability without patterns of preventable use errors, and with high acceptability ratings across all key attributes assessed. Preference over competitor autoinjectors was due to device ergonomics, visualization of dose progression, confidence of dose delivery, and overall ease of use.

Funding

Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-016-0286-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Abatacept autoinjector, Failure modes and effects analysis, Human factors engineering, Usability, Validation testing

Introduction

Abatacept, a fully human fusion protein, is the only biologic for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) that selectively modulates the CD80/CD86:CD28 co-stimulatory signal required for full T cell activation and is available in both intravenous and subcutaneous (SC) formulations. The intravenous formulation of abatacept has demonstrated efficacy in several patient populations, including methotrexate-naive patients with early RA [1] and patients with an inadequate response to methotrexate [2–5] or to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy [6, 7]. SC abatacept has been shown to be non-inferior to intravenous abatacept [8, 9]. The SC formulation, available as a pre-filled syringe, was first approved in the US in July 2011 for the treatment of moderate-to-severe RA in adults. Since then, SC abatacept has received marketing approval for the treatment of adult RA in numerous regions, including the EU, Japan, Canada, and Australia.

Although the SC delivery method affords users the benefit of self-injection at home, the pre-filled syringe requires several hand manipulations. This can be difficult for individuals with RA, as the disease often affects the small joints of the hand and impairs dexterity. To address this limitation and increase options for patients, a pre-filled, single-use autoinjector for abatacept (ClickJect®; Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ, USA) has been developed, with the aims of increasing the ease of the injection process and minimizing use error risk.

The abatacept autoinjector was designed and developed using human factors engineering (HFE). The autoinjector has a large rubberized grip and a hidden needle, and uses an automated injection process including automated delivery of the entire syringe contents. It also incorporates visual feedback to indicate the end of the injection, and shields the needle after injection. These features were designed to facilitate the injection process by improving handling ergonomics and reducing the number of hand manipulations, as well as to help patients who are new to self-injection and to overcome barriers to self-injection such as needle phobia.

This report describes the results of two studies that were conducted to assess the usability and acceptability of the abatacept autoinjector. A formative (pre-validation) study was performed to identify aspects of the product design and instructions for use (IFU) that could be further optimized to reduce the risk of user errors, while a summative study was performed as a final validation of the usability of the product and its labeling.

Methods

Two usability studies—formative and summative—were performed to measure the success of the HFE approach for device development (for details of the HFE, see Supplementary File 1). The goals of these studies were to determine: (1) whether the abatacept autoinjector, when provided with IFU, can be used without patterns of preventable use errors that would cause user or patient harm; and (2) if the autoinjector is acceptable for real-world use based on an assessment of key user needs (i.e., comfort, control, ease of use, confidence of dose) and overall acceptability.

The summative and formative studies were conducted by an independent company, Ipsos-Insight, LLC, separate from the study sponsor (Bristol-Myers Squibb). Participants were informed that the studies were testing a new autoinjector for an RA therapy, but no other specifics were shared. Throughout the studies, participants were blinded to the drug for which the autoinjector was intended, as well as to any sponsor involvement. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study; study risks were included in the informed consent.

Study Population

To replicate actual use, the study population included individuals from three defined user groups who met the following criteria: (1) patients with RA: both injection naive and experienced, with a minimum disease duration of 6 months and a diagnosis of moderate-to-severe RA (as evidenced by current treatment with a biologic or non-biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug); (2) caregivers: both injection naive and experienced, with a family member who has been diagnosed with RA; and (3) healthcare professionals (HCPs): injection experienced, who routinely work with and train patients with RA, and with a minimum of 2 years of experience. For the summative study, a minimum of 15 respondents per user group were recruited in accordance with the US Food and Drug Administration human factors guidance [10].

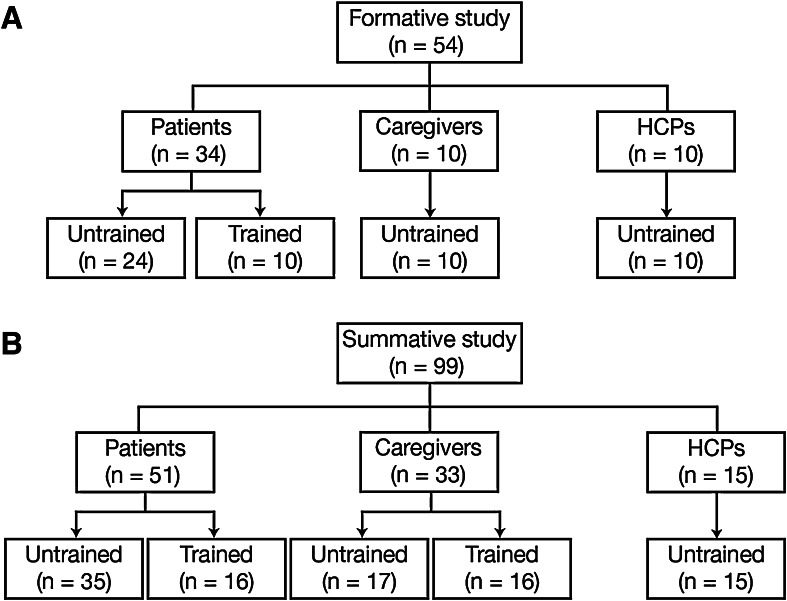

In each study, users were divided into two groups: trained and untrained (Fig. 1). To reduce the potential for use error, users should be trained, by an HCP, on the correct technique for preparing and performing injections when a therapy is prescribed, prior to the first injection. However, because there is no guarantee that all users will be adequately trained before their first use, the device was also validated with untrained participants. For the formative study (Fig. 1a), the trained arm comprised only patients; for the summative study (Fig. 1b), the trained arm included both patients and caregivers. Because most HCPs are not expected to receive any training on how to use the autoinjector, this group was not represented in the trained arm of either study. Prior to the studies, representatives from Bristol-Myers Squibb trained a nurse educator on the correct use of the autoinjector. The nurse educator in turn trained patients and caregivers using only the IFU and a device, to ensure the training was representative of that available in a routine clinical setting.

Fig. 1.

Trained and untrained user groups by study type. HCPs healthcare professionals

Use Environment

As these were simulated-use studies, efforts were made to simulate an end user’s actual use environment, and the study materials were designed to replicate the ergonomics and steps of actual administration. Injections are typically performed in low-traffic, low-distraction, low-noise settings, with normal office environment lighting conditions, and this environment was therefore replicated at the market research facilities where the studies were conducted. Study materials included an injection pad, which was strapped to the desired injection location (abdomen or thigh) in place of the injection site, a refrigerator (unplugged) for device storage, a hand sanitizer to mimic hand washing, and production-grade devices filled with medical-grade silicone oil to simulate the viscosity of abatacept and, hence, the injection time. The devices did not contain active therapy.

Study Procedures and Assessments

During the formative and summative studies, each participant was provided with the IFU and a device, and was asked to perform the necessary steps per the IFU to simulate an injection. The investigators evaluated each step (based on a risk analysis conducted prior to the study; see Supplementary File 1) using an assessment checklist, based on the perceptual, cognitive, and physical requirements of each step. High-priority tasks were defined as those that required correct completion for successful dose delivery.

The investigators then rated the observed performance as ‘correct performance’ (A), ‘performed with difficulty’ (D), or ‘use error’ (UE). A ‘performed with difficulty’ (D) classification included all close calls and near misses in which the user experienced confusion or difficulty, misinterpreted the IFU, or made an error that would result in mistreatment or harm, but then recovered and was able to continue so that no actual performance failure occurred. If a performance error occurred, but the user self-identified that the error had been made without prompting, it was also considered a ‘performed with difficulty’ (D) error, since the individual acknowledged the incorrect step and would self-correct with subsequent usage. A ‘use error’ (UE) classification included instances where the participant did not complete the step as appropriate. Following the usability assessment, the investigator and participant discussed the underlying causes of any difficulties (D) or use errors (UE) encountered during the simulated-use assessments, to ascertain if modifications could be incorporated into the product design or IFU to further optimize ease of use.

Participants were also asked to rate the acceptability of the autoinjector against a series of key attributes (i.e., comfort, control, ease of use, confidence of dose) and overall acceptability using a 7-point scale (1 = very unacceptable, 4 = neutral, and 7 = very acceptable). If time allowed, those participants who were experienced with an RA autoinjector were provided with their current or most recent autoinjector, allowed to re-familiarize themselves with it, and asked to provide competitive ratings. The participants did not perform a simulated injection with the competitor autoinjector. Participants experienced with an RA autoinjector were also asked for their preference of autoinjector based on their experiences during the simulated-use assessment.

A paired t test was used to identify statistical significance (P < 0.05) for the competitive rating analysis, while an exact binomial test was used for the user preference analysis. Finally, respondents were asked to name key positive features of the abatacept autoinjector, based on their simulated-use experience.

Results

The formative (pre-validation) study was conducted from February to March 2014 at market research centers in Fort Lee, NJ, USA; Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA; and San Francisco, CA, USA. A total of 34 patients with RA, 10 caregivers, and 10 HCPs were recruited (Fig. 1a). The summative (validation) study was conducted from August to September 2014 at market research centers in Fort Lee, NJ, USA; Baltimore, MD, USA; Stamford, CT, USA; and Dallas, TX, USA. A total of 51 patients with RA, 33 caregivers, and 15 HCPs were recruited (Fig. 1b). Respondents from Fort Lee, NJ, USA who had participated in the formative study were not eligible to participate in the summative study. The participant demographics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics of (A) patients with RA, (B) caregivers, and (C) healthcare professionals

| Parameter, %a | Formative study | Summative study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untrained (n = 24) | Trained (n = 10) | Untrained (n = 35) | Trained (n = 16) | ||

| (A) Patients with RA | |||||

| Injection experience | Naive | 33 | 30 | 20 | 25 |

| Experienced | 67 | 70 | 80 | 75 | |

| Injection experience device typeb | Autoinjector | 56 | 43 | 68 | 75 |

| Pre-filled syringe | 44 | 57 | 32 | 25 | |

| Age, years | 18–39 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| 40–49 | 38 | 10 | 23 | 25 | |

| 50–59 | 33 | 60 | 34 | 50 | |

| 60–69 | 21 | 30 | 29 | 19 | |

| 70–75 | 4 | 0 | 9 | 0 | |

| Sex | Female | 71 | 80 | 74 | 81 |

| Male | 29 | 20 | 26 | 19 | |

| Disease duration, yearsc | – | 6 | 11 | 8 | 5 |

| Education | High-school graduate | 21 | 10 | 11 | 19 |

| Some college | 29 | 60 | 40 | 31 | |

| College graduate/post-graduate | 50 | 30 | 48 | 50 | |

| Dexterity | No difficulty | 21 | 0 | 11 | 6 |

| Slight/moderate difficulty | 50 | 60 | 57 | 75 | |

| Considerable difficulty | 29 | 40 | 31 | 19 | |

| Current medication | MTX | 54 | 50 | 43 | 44 |

| Prednisone | 8 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| Parameter, % | Formative study | Summative study | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untrained (n = 10) | Untrained (n = 17) | Trained (n = 16) | ||

| (B) Caregivers | ||||

| Injection experience | Naive | 30 | 24 | 25 |

| Injection experienced | 70 | 76 | 75 | |

| Parameter, % | Formative study | Summative study | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untrained (n = 10) | Untrained (n = 15) | ||

| (C) Healthcare professionals | |||

| Experience | Minimum 2 years | 100 | 100 |

| Position | Medical assistant | 80 | 53 |

| Registered nurse | 20 | 40 | |

| Nurse practitioner | 0 | 7 | |

| Frequency of caring for at least 60 patients with RA in last 3 months | – | 90 | 100 |

| Frequency of training patients with RA on injectables | At least once a day | 30 | 20 |

| At least once a week | 70 | 80 | |

MTX methotrexate, RA rheumatoid arthritis

aPercentage values are presented, unless otherwise noted

bOf injection-experienced participants: formative untrained, n = 16; formative trained, n = 7; summative untrained, n = 28; summative trained, n = 12

cMedian values are presented

Simulated-Use Usability Assessment

Most participants completed each individual step of the simulation task without use errors (Table 2). In the formative study, two use errors were observed with the high-priority injection steps, both related to the respondent [one untrained patient and one HCP (i.e., untrained)] not holding the device in place long enough to complete the injection. Although these errors were observed, post-study actions were not taken to modify the device design or labeling, since the root-cause analysis identified the outcome to be a result of the respondents’ non-compliance to the protocol and study methodology, rather than a result of mental confusion or physical limitations. However, minor layout changes were made to the IFU to improve compliance with two (low-priority risk) use steps: ‘pinch skin’ and ‘check the autoinjector for damage’.

Table 2.

Frequency of completion of individual use steps during the formative and summative studies

| Task, % | Formative study | Summative study | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Caregivers | Healthcare professionals | Patients | Caregivers | Healthcare professionals | ||||

| Untrained (n = 24) | Trained (n = 10) | Untrained (n = 10) | Untrained (n = 10) | Untrained (n = 35) | Trained (n = 16) | Untrained (n = 17) | Trained (n = 16) | Untrained (n = 15) | |

| Take autoinjector out of refrigerator; wait 30 min | 96 | 100 | 90 | 100 | 97 | 100 | 88 | 100 | 93 |

| Wash hands | 92 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 94 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 93 |

| Check expiration date | 96 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 91 | 100 | 94 | 100 | 93 |

| Check autoinjector for damage | 79 | 80 | 100 | 100 | 89 | 100 | 94 | 100 | 87 |

| Check the liquid | 92 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 97 | 100 | 94 | 100 | 100 |

| Choose an injection site | 96 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Clean the site | 96 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 97 | 100 | 82 | 100 | 93 |

| Remove needle covera | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Position the autoinjector | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Pinch skin | 88 | 100 | 80 | 100 | 91 | 100 | 100 | 94 | 93 |

| Push down to unlock the autoinjectora | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Press buttona | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Hold for count and/or wait until blue indicator stops movinga | 96 | 100 | 100 | 90 | 97 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Dispose used autoinjector into sharps container | 100 | 100 | 90 | 100 | 94 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Steps classified as ‘A—correct completion’ plus ‘D—performed with difficulty’

aTasks highlighted in bold are high-priority tasks, defined as those that required correct completion for successful dose delivery

In the summative study, all participants except one (an untrained patient) completed all of the high-priority injection steps (Table 2). The exception related to the ‘hold for count and/or wait until blue indicator stops moving’ step. The use error was deemed an artifact of the study, as the patient was currently using a competitor autoinjector and was applying their expectations of the ‘feel’ in the skin of an injection to indicate the appropriate hold time. Since this tactile end-of-dose indication does not apply to a simulated-use setting, no mitigation steps were deemed necessary.

Simulated-Use Acceptability Assessment

Average acceptability scores for the device were consistently high for each user group for all measures (comfort, control, ease of use, confidence of dose, overall acceptability) (Table 3). In the formative study, all 54 participants responded (34 patients, 10 caregivers, and 10 HCPs); mean overall acceptability scores (out of 7) for patients, caregivers, and HCPs were 6.6, 7.0, and 6.8, respectively. In the summative study, 94 out of 99 participants responded (48 patients, 31 caregivers, and 15 HCPs); mean overall acceptability scores for patients, caregivers, and HCPs were 6.6, 6.8, and 6.8, respectively.

Table 3.

Participant user experience data

| Rating | Formative study | Summative study | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n = 34) | Caregivers (n = 10) | Healthcare professionals (n = 10) | Patients (n = 48) | Caregivers (n = 31) | Healthcare professionals (n = 15) | |

| Comfort | 6.5 (0.8) | 6.6 (1.0) | 6.8 (0.6) | 6.4 (1.0) | 6.3 (1.0) | 6.9 (0.4) |

| Control | 6.6 (0.9) | 6.8 (0.4) | 6.7 (1.0) | 6.9 (0.4) | 6.8 (0.5) | 6.8 (0.4) |

| Ease of use | 6.7 (0.8) | 6.9 (0.3) | 6.8 (0.4) | 6.6 (0.8) | 6.9 (0.3) | 6.7 (0.6) |

| Confidence of dose | 6.8 (0.5) | 7.0 (0.0) | 6.4 (1.6) | 6.6 (0.7) | 6.9 (0.4) | 6.7 (0.6) |

| Overall acceptability | 6.6 (0.8) | 7.0 (0.0) | 6.8 (0.4) | 6.6 (0.6) | 6.8 (0.5) | 6.8 (0.4) |

All values are expressed as mean (standard deviation)

Each score was quantified using a 7-point scale, where 1 = very unacceptable, 4 = neutral, and 7 = very acceptable

Current Autoinjector User Subgroup Analysis

Among patients who had previously administered injections with a competitor autoinjector, overall mean acceptability ratings were significantly greater for the abatacept autoinjector versus competitor autoinjectors across all user groups in both studies [formative study: patients 6.7 vs 5.2 (P = 0.0001), caregivers 7.0 vs 4.6 (P = 0.0093), HCPs 6.8 vs 5.1 (P = 0.0020); summative study: patients 6.5 vs 5.9 (P = 0.0404), caregivers 6.8 vs 5.8 (P = 0.0047), HCPs 6.8 vs 5.1 (P = 0.0002); Table 4]. In the individual categories of comfort, control, ease of use, and confidence of dose, all groups rated the abatacept autoinjector at least the same or superior to competitor autoinjectors; this difference was significant for almost all parameters, across all user groups, and in both studies (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparative user experience data following abatacept autoinjector use in (A) the formative study or (B) the summative study, from participants who had previously administered injections with an alternative autoinjector

| Rating | Patients (n = 12) | Caregivers (n = 5) | Healthcare professionals (n = 10) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean abatacept autoinjector rating | Mean competitor autoinjector rating | Mean paired difference | Mean abatacept autoinjector rating | Mean competitor autoinjector rating | Mean paired difference | Mean abatacept autoinjector rating | Mean competitor autoinjector rating | Mean paired difference | |

| (A) Formative study | |||||||||

| Comfort | 6.6 | 4.6 | P = 0.0033 | 7.0 | 4.2 | P = 0.0135 | 6.8 | 4.5 | P < 0.0001 |

| Control | 6.8 | 4.6 | P = 0.0025 | 7.0 | 4.0 | P = 0.0132 | 6.7 | 4.6 | P = 0.0095 |

| Ease of use | 7.0 | 5.9 | P = 0.0006 | 7.0 | 5.2 | P = 0.0533 | 6.8 | 5.2 | P = 0.0046 |

| Confidence of dose | 6.8 | 6.3 | P = 0.0819 | 7.0 | 5.8 | P = 0.2080 | 6.4 | 5.6 | P = 0.2999 |

| Overall acceptability | 6.7 | 5.2 | P = 0.0001 | 7.0 | 4.6 | P = 0.0093 | 6.8 | 5.1 | P = 0.0020 |

| Rating | Patients (n = 25) | Caregivers (n = 12) | Healthcare professionals (n = 13) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean abatacept autoinjector rating | Mean competitor autoinjector rating | Mean paired difference | Mean abatacept autoinjector rating | Mean competitor autoinjector rating | Mean paired difference | Mean abatacept autoinjector rating | Mean competitor autoinjector rating | Mean paired difference | |

| (B) Summative study | |||||||||

| Comfort | 6.4 | 5.2 | P = 0.0157 | 6.4 | 5.4 | P = 0.0671 | 6.8 | 5.2 | P = 0.0017 |

| Control | 6.9 | 5.6 | P = 0.0002 | 6.9 | 5.8 | P = 0.0081 | 6.8 | 4.5 | P = 0.0001 |

| Ease of use | 6.5 | 5.8 | P = 0.0210 | 6.8 | 5.8 | P = 0.0039 | 6.6 | 5.0 | P = 0.0012 |

| Confidence of dose | 6.4 | 6.4 | P = 0.8960 | 6.8 | 6.3 | P = 0.2098 | 6.7 | 5.2 | P = 0.0112 |

| Overall acceptability | 6.5 | 5.9 | P = 0.0404 | 6.8 | 5.8 | P = 0.0047 | 6.8 | 5.1 | P = 0.0002 |

Each score was quantified using a 7-point scale, where 1 = very unacceptable, 4 = neutral, and 7 = very acceptable

Analyses were restricted to those participants who provided both abatacept and competitor autoinjector ratings

Participants demonstrated a strong preference for the abatacept autoinjector over competitor autoinjectors (Table 5). When preference data from the two studies were combined, a significantly greater number of participants in each user group preferred the abatacept autoinjector over their current or most recent autoinjector [patients 85.7% vs 14.3% (P = 0.00002), caregivers 84.2% vs 15.8% (P = 0.00443), HCPs 95.0% vs 5.0% (P = 0.00004)]. For the individual studies, this preference remained significant for patients in the formative (P = 0.00049) and summative (P = 0.01062) studies, and for HCPs in the summative study (P = 0.00049). Although the other comparisons were not significant, all preference data showed at least a trend in favor of the abatacept autoinjector in both studies.

Table 5.

Autoinjector preferences from participants who had previously administered injections with an alternative autoinjector

| Respondents, n (%) | Formative study | Summative study | Total of formative and summative studies | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abatacept autoinjector preference | Competitor autoinjector preference | Test preference of abatacept autoinjectora | Abatacept autoinjector preference | Competitor autoinjector preference | Test preference of abatacept autoinjectora | Abatacept autoinjector preference | Competitor autoinjector preference | Test preference of abatacept autoinjectora | |

| Patients | 12 (100) | 0 (0.0) | (73.54, 100.00); P = 0.00049 | 18 (78.3) | 5 (21.7) | (56.30, 92.54); P = 0.01062 | 30 (85.7) | 5 (14.3) | (69.74, 95.19); P = 0.00002 |

| Caregivers | 5 (100) | 0 (0.0) | (47.82, 100.00); P = 0.06250 | 11 (78.6) | 3 (21.4) | (49.20, 95.34); P = 0.05737 | 16 (84.2) | 3 (15.8) | (60.42, 96.62); P = 0.00443 |

| HCPs | 7 (87.5) | 1 (12.5) | (47.35, 99.68); P = 0.07031 | 12 (100) | 0 (0.0) | (73.54, 100.00); P = 0.00049 | 19 (95.0) | 1 (5.0) | (75.13, 99.87); P = 0.00004 |

aDisplayed as (95% confidence interval); P value

Key Positive Features

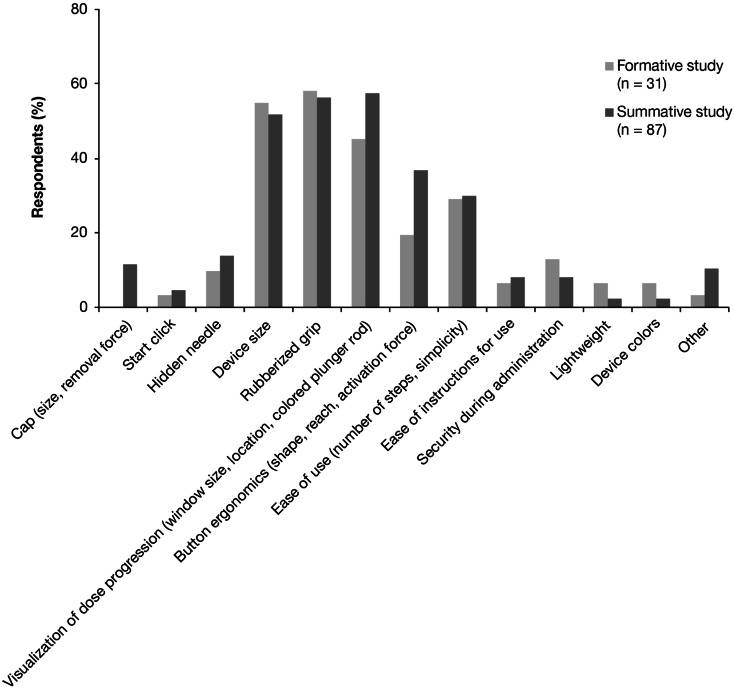

In total, 31 formative study participants and 87 summative study participants reported on the positive features of the abatacept autoinjector. The most frequently noted positive features were: rubberized grip (formative study, noted by 58% of respondents; summative study, 56%), device size (formative, 55%; summative, 52%), visualization of dose progression (window size and location, colored plunger rod; formative, 45%; summative, 57%), button ergonomics (shape, reach, activation force; formative, 19%; summative, 37%), and ease of use (number of steps, simplicity; formative, 29%; summative, 30%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Key positive factors of the abatacept autoinjector reported by respondents

Discussion

The independently conducted studies reported here found that the newly designed autoinjector for the SC delivery of abatacept in patients with RA was easy to use, with low residual risk to users in a real-world setting. Most participants, whether patients, caregivers, or HCPs, trained or untrained, performed all high-priority use steps correctly. Participants rated the abatacept autoinjector highly for user experience in terms of comfort, control, ease of use, confidence of dose, and overall acceptability, with scores nearing the maximum of the 7-point scale used. All user groups across both studies rated the abatacept autoinjector significantly higher than competitor devices for overall acceptability, and when preference data from both studies were combined, significantly more participants in each user group preferred the abatacept autoinjector over their current or most recent device. The drivers for the positive ratings and preference could be grouped into three main categories: device ergonomics (size, rubberized grip, button reach, force to activate), which provides comfort and security during injection; visualization of dose progression (size and location of window, colored plunger rod), which provides confidence of dose delivery; and simplicity of the process, which contributes to the overall ease of use of the device.

Because RA can affect the small joints of the hands, many patients with RA suffer from compromised dexterity. In addition to interfering with activities of daily living, poor dexterity can affect the ability to perform the steps required for self-injection in patients who would otherwise be eligible for an SC therapy. Autoinjectors are available for the administration of many SC therapies for chronic conditions, including those in which patients have impaired dexterity [11, 12]. The single-use, pre-filled autoinjector described here was developed following the principles of HFE, to help users to inject one dose of SC abatacept in a home environment. As evidenced by the results of the current studies, the new autoinjector is an important advance for patients receiving, or eligible to receive, SC abatacept, as it increases the ease of the injection process without introducing usability challenges.

In both the formative and summative studies, the vast majority of respondents completed each individual step of the simulated injection without use errors. These results demonstrate that, overall, both trained and untrained users were able to operate the autoinjector safely and effectively to deliver the SC injection by following the IFU.

Furthermore, the overall preference in favor of the abatacept autoinjector over other available injection devices across a range of attributes indicates that the device’s features were favored by users with experience of such devices. The fact that similar results were obtained across the two studies provides further credence to these findings. These data also indicate that the device features designed in early development (i.e., shape, rubberized grip, placement/size of window, colored plunger rod, button ergonomics) contributed to the favorable comfort, control, confidence of dose, ease of use, and acceptability ratings for the device, indicating value by the end users. Furthermore, as no patterns of error were observed in the studies, use risk was mitigated.

A limitation of these evaluations is the simulated-use design of the studies, rather than autoinjector use in a clinical setting. However, according to US Food and Drug Administration guidance, simulation testing, as conducted here, is an acceptable method for assessing the safe and effective use of an autoinjector device. Greater support for the ease of use of the autoinjector may have been obtained by restricting the study population to patients with more severe hand deformity, for whom any improvement would be most beneficial. In addition, respondent numbers were low in the subgroup analyses. A further limitation is the lack of a simulated injection using the competitor autoinjector device; permitting a simulated injection with a competitor device may have allowed for a more accurate comparison with the abatacept autoinjector versus relying on participant memory. The time span between using and rating the competitor device may have influenced the comparative data; therefore, not capturing and adjusting for this time difference may affect the interpretation of these results. Lastly, the autoinjector was branded in order for participants to evaluate its colored design features. As such, HCPs may have ascertained which product the autoinjector was designed to deliver.

Conclusions

The abatacept autoinjector was found to be highly acceptable against key measures of comfort, control, ease of use, confidence of dose, and overall acceptability in two independently conducted simulated-use studies. High overall acceptability ratings were achieved, and these ratings were significantly greater than those for competitor devices. In addition, a significantly greater number of participants in each user group preferred the abatacept autoinjector over their current or most recent autoinjector.

Participants’ positive experiences with the abatacept autoinjector can be attributed to the following key features: device ergonomics (size, shape, rubberized grip, button reach, and activation force), which provides comfort and security during injection; visualization of dose progression (size and location of window, colored plunger rod), which provides confidence of dose delivery; and simplicity of the process, which contributes to the overall ease of use of the device. These results show that HFE optimized the device design and IFU of the abatacept autoinjector to ensure its effective use by patients, caregivers, and HCPs without patterns of preventable use errors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship, article processing charges, and the open access charge for this study were funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Professional medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Carolyn Tubby, PhD, at Caudex and was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Disclosures

MS is a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Antares, BMS, Eli Lilly, Horizon, JNJ, Roche, and UCB, and has participated in speakers’ bureaus for AbbVie. JK, EJ, ES, and CL are employees of Bristol-Myers Squibb. AD and RS have received consulting fees/other from Ipsos-Insight, LLC.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study; study risks were included in the informed consent.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

References

- 1.Westhovens R, Robles M, Ximenes AC, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of abatacept in methotrexate-naive patients with early rheumatoid arthritis and poor prognostic factors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(12):1870–1877. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.101121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kremer JM, Genant HK, Moreland LW, et al. Effects of abatacept in patients with methotrexate-resistant active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(12):865–876. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-12-200606200-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kremer JM, Russell AS, Emery P, et al. Long-term safety, efficacy and inhibition of radiographic progression with abatacept treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate: 3-year results from the AIM trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(10):1826–1830. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.139345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smolen J, Dougados M, Gaillez C, et al. Remission according to different composite disease activity indices in biologic-naïve patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with abatacept or infliximab plus methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(Suppl 10):S477. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westhovens R, Kremer JM, Emery P, et al. Consistent safety and sustained improvement in disease activity and treatment response over 7 years of abatacept treatment in biologic-naïve patients with RA. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(Suppl 3):577. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Genovese MC, Becker JC, Schiff M, et al. Abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibition. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(11):1114–1123. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiff M, Pritchard C, Huffstutter JE, et al. The 6-month safety and efficacy of abatacept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who underwent a washout after anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy or were directly switched to abatacept: the ARRIVE trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(11):1708–1714. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.099218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Genovese MC, Cobos AC, Leon G, et al. Subcutaneous (SC) abatacept (ABA) versus intravenous (IV) ABA in patients (pts) with rheumatoid arthritis: long-term data from the ACQUIRE (Abatacept Comparison of sub[QU]cutaneous versus intravenous in Inadequate Responders to methotrexatE) trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(Suppl 10):S150. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Genovese MC, Tena CP, Covarrubias A, et al. Subcutaneous abatacept for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: longterm data from the ACQUIRE trial. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(4):629–639. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Food and Drug Administration. Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff—Applying Human Factors and Usability Engineering to Optimize Medical Device Design. 2011. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/ucm259748.htm. Accessed 3 June 2015.

- 11.Schwarzenbach F, Dao TM, Grange L, et al. Results of a human factors experiment of the usability and patient acceptance of a new autoinjector in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:199–209. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S50583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phillips JT, Fox E, Grainger W, Tuccillo D, Liu S, Deykin A. An open-label, multicenter study to evaluate the safe and effective use of the single-use autoinjector with an Avonex(R) prefilled syringe in multiple sclerosis subjects. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:126. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.