Abstract

Introduction:There are many ideas concerning the etiology and pathogenesis of preeclampsia including endothelial dysfunction, inflammation and angiogenesis. Elevated levels of total homocysteine (Hcy) and lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)] are risk factors for endothelial dysfunction. This study aimed to evaluate the effect of high dose folic acid (FA) on serum Hcy and Lp(a) concentrations with respect to methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) polymorphisms 677C→T during pregnancy.

Methods: In a prospective uncontrolled intervention, 90 pregnant women received 5 mg FA supplementation before pregnancy till 36th week of pregnancy. The MTHFR polymorphisms 677C→T, serum lactate dehydrogenase activity, urine protein and creatinine concentrations were measured before starting folic acid administration. Serum levels of Hcy and Lp(a) were determined before and after completion of folic acid supplementation period.

Results: Supplementation of the patients with FA for 36 week decreased the median (minimum– maximum) levels of serum Hcy from 11.40 μmol/L (4.40-28.70) to 9.70 (1.60-20.80) μmol/L (p=0.001). There was no significant change in serum Lp(a) after FA supplementation (p=0.17). The overall prevalence of genotypes in pregnant women that were under study for MTHFR C677T polymorphism was 53.3% CC, 26.7% CT and 20.0% TT. There was no correlation between decreasing level of serum Hcy in the patients receiving FA and MTHFR polymorphisms.

Conclusion:Although FA supplementation decreased serum levels of Hcy in different MTHFR genotypes, serum Lp(a) was not changed by FA supplements. Our data suggests that FA supplementation effects on serum Hcy is MTHFR genotype independent in pregnant women.

Keywords: Folic acid, Homocysteine, Lipoprotein (a), Pregnancy, MTHFR polymorphism

Introduction

Preeclampsia is one of the most important complications dduring pregnancy with unknown etiology which is associated with hypertension and proteinuria with a prevalence of 5-8% of all pregnancies worldwide. There are many ideas concerning the etiology and pathogenesis of preeclampsia including endothelial dysfunction, inflammation and angiogenesis.1 Homocysteine (Hcy) is a toxic, non-proteinogenic, sulfur-containing, highly reactive amino acid, which is synthesized in the course of protein catabolism by the conversion of methionine to cysteine.2 Methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) catalyzes the reduction of 5, 10-methylenetetrahydrofolate to 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, which is the major circulating form of folate. The 5-methyltetrahydrofolate is a donor of methyl for the vitamin B12-dependent remethylation of Hcy to methionine. It has been shown that the most important reason for hyperhomocysteinemia and/or lack of methionine is the polymorphism of MTHFR gene.3 MTHFR 677C>T mutation has been recognized with 40% reduction in its activity of the CT (heterozygote) and with very low activity (about 70% reduction) of the TT (homozygote) form.4 Recent evidence suggested a relationship between high levels of blood circulating Hcy in women with gestational hypertension and preeclampsia.5 Increased circulating Hcy as a predisposing risk factor for peripheral vascular diseases, could be one of the independent risk factors for preeclampsia.6

Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] as a plasma lipoprotein consists of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) particle and the glycoprotein apolipoprotein(a) covalently bounded to apolipoprotein B100 of the LDL-C particle.7 Apolipoprotein (a) has been reported to have structural similarities to plasminogen and to inhibit plasminogen activity in-vitro. In consequence, a reduction in the activity of plasminogen leads to a reduction in the clot lysis. Pregnancy is a condition of hyperlipidemia and hypofibrinolysis which may be essential for normal placental development.8 Preeclampsia demonstrates an exaggerated inhibition of the fibrinolysis which, in-part, results from an increase in plasma plasminogen inhibition. Serum Lp(a) level is elevated in the preeclampsia which is associated with severity of the disease.9

In vitro studies have demonstrated that Hcy enhances the binding of Lp(a) to fibrin by altering fibrinolysis.10-14 In the preeclampsia, a more exacerbation of the hypercoagulable condition is noticed, compared to the normal pregnancy.15 Folic acid (FA) supplementation can increase serum folate concentrations and decline Hcy concentrations.16 Hyperhomocysteinemia can be considered as one of the chronic oxidative stress factors which enhances the vascular inflammation that results in increase in the concentrations of fibrinogen and Lp(a). Taking into account the possible interactions between Hcy, fibrinogen, and Lp(a), vitamin B groups may also affect the status of fibrinogen and Lp(a).17 Limited studies have investigated the association between genetic polymorphisms in MTHFR gene and the effects of FA supplementation on serum Hcy levels. This study aimed to assess if MTHFR genotypes (677C→T) can influence plasma Hcy and Lp(a) concentrations in response to high dose of FA supplementation.

Materials and methods

Materials

Serum concentrations of Hcy were measured by commercially Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) kits (AXIS Co). Lp(a) was obtained from Pars Azmoon Co (Tehran, Iran). Serum urea, uric acid, lactic dehydrogenase, creatinine, urine protein and urine creatinine were determined using commercial reagents with an automated chemical analyzer (Abbott Analyzer, USA). Genomic DNAs were extracted from whole blood according to the manufacturer’s protocol in Kit (RON’S Blood and Cell DNA Mini Kit).

Subjects

This study was set up as a clinical trial including one hundred thirty nulliparous women who visited the AL-Zahra Hospital, Tabriz Iran, from September 2013 to November 2014 for prenatal tests and planning to be pregnant. All the participants had signed written informed consent. Among the participants only healthy women aged between 20-30 years old without any history of medical problems including heart disease, chronic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal disease, collagen tissue disease, preterm delivery, abortion, and liver disease were included in the study. Sever preeclampsia was defined as blood pressure (BP) ≥160/110 mm Hg, proteinuria≥2.0 g/24 h, serum creatinine>1.2 mg/dL unless known to be previously elevated, platelets <100.000/mm3 , microangiopathic hemolysis (increased LDH), persistent headache or other cerebral or visual disturbance.

Sample collection and analysis

Baseline venous blood samples were collected after overnight fasting at 3-month intervals before conception. After collecting baseline samples, participants received FA (5 mg/day) for 36 weeks after initiation of pregnancy. The participants were contacted every week and asked during each visit to declare whether they took FA supplementation or not. Second sampling was done 36 weeks after pregnancy. Mothers who had abortion and taking medications other than calcium and ferrous sulfate and did not complete the follow up visit were excluded from the study. Serum samples were isolated from whole blood and after centrifugation (at 3000 rpm) for 20 min stored in a freezer at -70°C for Lp(a) and Hcy analysis.

Genotyping of the MTHFR gene variant

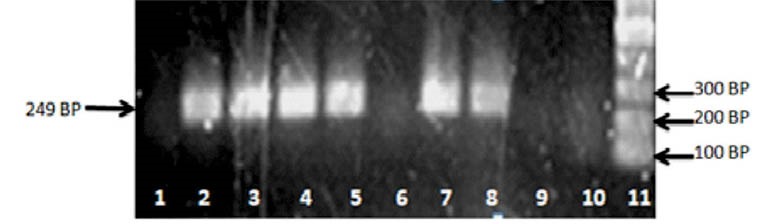

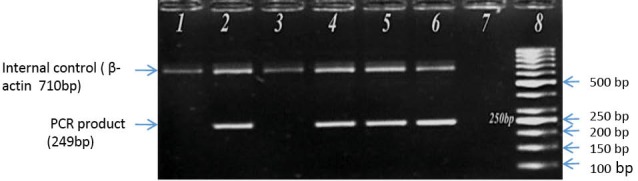

The quantity and quality of the extracted DNA were checked using UV absorption measurement, Eopoch. BioTek (Winooski, VT, USA). The A260/A280 ratio of DNA samples was in high quality between 1.7–2.0A. The PCR solution contained 110 ng genomic DNA, 1x PCR buffer, 0.3 mM of each primer, 10 nmol of each dNTP, 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 1 U Taq polymerase in a final volume of 25 µL. Polymorphisms of MTHFR (677) was evaluated by using ARMS-PCR method. In ARMS-PCR method, amplification of DNA was performed using three primers for each polymorphism, one forward primer (TGCTGTTGGAAGGTGCAAGAT) and two reverse primers (for mutant primer; GCGTGATGATGAAATCGA, for normal primer; GCGTGATGATGAAATCGG). Primer Blast at NCBI site and primer 3Plus software for primer design were applied. PCR products were separated on 1% agarose gel. To determine DNA fragments, Thermo Scientific Gene Ruler 50 bp DNA Ladder was used (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 .

Agarose gel electrophoretogram shows the detection of MTHFR 677C > T polymorphism by ARMS-PCR technique. Line 1, 2: CC (which amplified just by normal DNA primers). Line 3, 4: CC (which amplified just by normal DNA primers). Line 5, 6: CT (that amplified by either normal or mutated DNA primers). Line 7: Negative Control (without DNA sample which amplified by neither of primers). Line 8: Ladder.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS software version 18.0 (SPSS Ins, Chicago, IL, USA). Results were expressed as median (minimum-maximum), or mean±SD. We checked the distribution of variables by Kolmogorov– Smirnov test, Skewness and also Kurtosis of data before starting statistical analysis. The results showed that our data is not normally distributed so we used Kruskal-Wallis test to compare three groups of cases (CC, TT and CT genotypes) on one variable. The Wilcoxon and Kruskal-Wallis tests were also applied to assess the significance of differences between the baseline and delivery time. Correlation was evaluated by Pearson’s test and the statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

One hundred and thirty pregnant women were initially recruited. Forty women failed to complete the study period (10 cases had abortion, 2 cases had multiple pregnancies, 13 cases quit taking their supplements and 15 cases did not come to the second round of sampling 36 weeks after pregnancy) and all the analysis were performed on a total of 90 cases. The demographic characteristics and biochemical data of the population under studying were summarized in Table 1. There was no clinically apparent case of hypertension. The mean changes of Hcy and Lp(a) at the baseline and at the 36th week of pregnancy were shown in Table 2. Although the mean serum levels of Hcy at the 36th week of pregnancy were significantly lower in the women receiving FA supplementation (p = 0.001), no statistically significant changes were observed in Lp(a) levels (p= 0.17). The results from laboratory analysis of Hcy and Lp(a) levels at the baseline and at the 36th week of pregnancy after treatment with FA supplementation, stratified by MTHFR C677T were shown in Table 3. The prevalence of MTHFR C677T polymorphisms 677 CC, 677 CT, and 677 TT were 53.3%, 26.7%, and 20.0%, respectively. Although there was no significant association between serum Lp(a) levels and MTHFR C677T genotype (p>0.1, In all three genotypes), Hcy levels decreased markedly in all three genotypes (CC: P<0.001, CT: p<0.001, TT: p<0.02).

Table 1 . Demographic characteristics and biochemical data of pregnant women .

| Variable |

Pregnant woman (n= 90)

(Mean ± SD) |

| Age (years) | 27.07 ± 4.86 |

| LDH (IU/L) | 359.56 ± 82.01 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 3.89 ± 1.02 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 27.31 ± 1.18 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.80 ± 0.11 |

| Urine creatinine (g/24 h) | 0.73 ± 0.09 |

| Platelet count (µL) | 229.11 ± 49.21 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.37 ± 3.63 |

| Systolic BP(mm Hg) | 119.78 ± 9.17 |

| Diastolic BP(mm Hg) | 80.00 ± 3.69 |

| Urine protein (mg/24 h) | 148.42 ± 79.04 |

LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; BMI: Body Mass Index.

Table 2 . The mean changes of homocysteine and lipoprotein (a) concentrations at baseline and at the 36th week of pregnancy after treatment with folic acid supplementation .

| Parameters |

Baseline

n=90 |

36thweek

n=90 |

p-value a |

| Hcy (µmol/L) | 11.40 (4.40-28.70) | 9.70 (1.60-20.80) | 0.001* |

| Lp(a) (mg/ dL) | 3.60 (0.47-33.00) | 4.30 (0.37-31.00) | 0.17 |

Hcy: Homocysteine; Lp (a): Lipoprotein (a); Data are expressed as median (minimum–maximum).

aBefore treatment vs. after treatment with folic acid supplementation. (Values were obtained by a Wilcoxon test.)

*Significant difference.

Table 3 . The mean changes of homocysteine and lipoprotein (a) concentrations at baseline and at the 36th week of pregnancy after treatment with folic acid supplementation stratified by MTHFR C677T genotype .

| Parameters |

CC

n =48 % =53.3 |

CT

n =24 % =26.7 |

TT

n =18 % =20.0 |

p-value |

| Hcy (µmol/L) [median (minimum–maximum)] | ||||

| Baseline | 12.40 (4.40-28.70) | 10.45 (6.80-21.00) | 9.95 (6.00-20.60) | 0.06a |

| 36th week | 11.30 (1.60-20.80) | 7.75 (5.80-17.70) | 9.15 (3.50-18.70) | 0.08b |

| p-value | 0.001c | 0.001c | 0.02c | |

| Lp (a) (mg/dL) [median (minimum–maximum)] | ||||

| Baseline | 4.35 (0.65-33.00) | 3.60 (.47-17.80) | 3.20 (1.30-10.6) | 0.58a |

| 36th week | 4.40 (1.00-31.00) | 4.40 (2.20-16.60) | 3.60 (0.37-26.90) | 0.55b |

| p-value | 0.16c | 0.44c | 0.68c |

Hcy: Homocysteine; Lp(a): Lipoprotein (a)

aComparison of Hcy and Lp(a) among different genotypes before treatment(Values were obtained by a Kruskal-Wallis test).

b Comparison of Hcy and Lp(a) among different genotypes after treatment (Values were obtained by a Kruskal-Wallis test).

cBefore treatment vs. after treatment with folic acid supplementation in each genotype (Values were obtained by a Wilcoxon test).

Discussion

The endothelial cell injury in preeclampsia has multifactorial causes. Typical pathological lesions in the placenta, affected by preeclampsia, are fibrin deposits, acute atherosclerosis and thrombosis. The resemblance between the lesions of preeclampsia and atherosclerosis has led to assumptions of a common pathophysiological pathway. Elevated plasma Lp(a) and Hcy concentrations were identified as risk factors for atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases.11 In preeclampsia, an increased exposure to risk factor(s) such as abruption placenta, acute renal failure, cerebrovascular and cardiovascular complications, and maternal death have been reported.18,19 Our data showed that supplementation of pregnant women with FA decreased the total plasma Hcy levels. Sayyah et al observed a protective role for FA in the group who continued FA in a dose of 5 mg/day through gestation. In that study the Hcy levels were lower than the group who received 0.5 mg/day and blood pressure was not increased to the eclampsia/preeclampsia borders.20 Papadopoulou et al showed that high doses of supplemental FA (>5 mg/day) in early-to-mid gestation may prevent preterm birth, low birth weight, and small for gestational age neonates.21 In the present study, we found that the mean serum levels of Hcy at the 36th week of pregnancy after treatment with FA (5 mg/day) supplementation were significantly lower in comparison with baseline state. Our study confirmed McDowell et al results in that the high doses of FA (5 mg/day) significantly reduced the total Hcy levels.22 Although Adank et al demonstrated that weekly high-dose FA supplement (2,800 µg) was effective as a daily supplement in lowering Hcy concentrations in healthy women of childbearing age,23 Li et al24 suggested that daily consumption of 400 μg FA alone during early pregnancy cannot prevent the occurrence of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Our findings were not consistent with Fernandez et al results which observed basal Hcy levels were not affected by FA in a dose of 1 mg/day after three months supplementation.25 Often this supplementation does not protect against hyperhomocysteinemia, possibly because the usual daily doses of FA are too low.

It has been shown that, there is a 2-fold increase in Lp(a) during normal pregnancy, which may influence fibrinolysis.26 On the other hand, Parvin and Mori et al pointed out an association between elevated levels of Lp(a) and preeclampsia.27,28 Satter and Baksu et al showed no statistically significant differences between normotensive pregnant, and preeclamptic women, with respect to plasma Lp(a) levels.26,29 Harpel et al30 revealed that Hcy, even at a low concentration of 8 µmol/L, could modify the structure of Lp(a) by exposing lysine-binding domains in the apo(a) molecule. In consequence, the binding between Lp(a) and fibrin was significantly increased. Activation of coagulation in preeclampsia occurred at an early phase of the disease and antedated the clinical symptoms.15 Furthermore, it was demonstrated that the administration of vitamin B causes decline of Hcy, Lp(a) and fibrinogen.17 The result of our study showed that by administrating FA, Hcy levels were decreased in all three MTHFR genotypes but Lp(a) status were not statistically influenced. Also no significant correlation between serum Hcy and Lp(a) concentrations during the FA supplementation was detected.

The MTHFR polymorphism is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease, neural tube defects, occlusive arterial disease, cognitive decline and osteoporosis. Polymorphism of MTHFR C677T caused a decrease in enzyme activity, which may lead to an increase in the concentration of plasma Hcy and lower levels of serum folate, particularly in those with low folate intake.31 Xianhui et al demonstrated that MTHFR C677T polymorphism not only affects on Hcy concentrations at baseline and after FA treatment, but also can modify responses to various dosages of FA supplementation.32 They found that after four or eight weeks of treatment with high dose of FA, subjects with MTHFR 677 TT genotype had significantly greater decrease in Hcy levels compared to CC genotype. We found that the magnitude of the reduction in Hcy levels with FA administration was irrespective of MTHFR genotypes. In contrast, several authors33,34 demonstrated that the effect of FA supplementation was most different in persons with the highest Hcy concentrations at baseline and in persons homozygous for the 677 C→T mutation of the MTHFR-gene. Williams et al showed that MTHFR genotype CC homozygote’s (without the 677C→T polymorphism) with normal blood pressure had a larger reduction in Hcy concentrations in response to FA (5 mg) than did T allele carriers.35 The discrepancies can be explained by applied methods, study design, sample sizes and ethnicity of study populations. Similar to our results, several authors, demonstrated that the effect of FA supplementation may be unrelated to MTHFR genotype.36,37

Additional large sample studies also are needed to further examine the relationship of FA treatment with Hcy and Lp(a) change and the possible effect of high dose of FA which was administrated throughout pregnancy on serum Hcy and Lp(a) levels in MTHFR (677C→T).

Conclusion

Based on our findings, the FA supplementation can decrease the serum levels of Hcy, while Lp(a) status was not statistically influenced. Further, the effect of FA supplementation may be unrelated to the MTHFR genotype in the pregnant women.

Acknowledgements

The authors are extremely thankful to all the staff of Drug Applied Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran and also to all of the drivers participated in this study.

Ethical issues

Our study protocol was approved by Ethical Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Ethics code: 92/2-3/8) in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) and given the ID: IRCT2014010715903N2. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Competing interests

There is none to be disclosed. No financial support was received for this study.

Research Highlights

What is current knowledge?

√ Elevated total homocysteine (Hcy) and lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)] are risk factors for the endothelial dysfunction.

What is new here?

√ The FA supplementation can decrease the serum levels of Hcy in all three methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphisms (MTHFR), however the serum level of Lp(a) did not change in the pregnant women.

References

- 1.Khosrowbeygi A, Ahmadvand H. Circulating levels of homocysteine in preeclamptic women. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 2011;37:106–9. doi: 10.3329/bmrcb.v37i3.6196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo HY, Xu FK, Lv HT, Liu LB, Ji Z, Zhai XY. et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia independently causes and promotes atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2014;11:74. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-5411.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Messedi M, Frigui M, Chaabouni K, Turki M, Neifer M, Lahiyani A. et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T and A1298C polymorphisms and variations of homocysteine concentrations in patients with Behcet’s disease. Gene. 2013;527:306–10. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Czeizel AE, Dudás I, Vereczkey A, Bánhidy F. Folate deficiency and folic acid supplementation: the prevention of neural-tube defects and congenital heart defects. Nutrients. 2013;5:4760–75. doi: 10.3390/nu5114760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Zhao N, Qiu J, He X, Zhou M, Cui H. et al. Folic acid supplementation and dietary folate intake, and risk of preeclampsia. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015 doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mujawar SA, Patil VW, Daver RG. Study of serum homocysteine, folic acid and vitamin B12 in patients with preeclampsia. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2011;26:257–60. doi: 10.1007/s12291-011-0109-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Todoric J, Handisurya A, Leitner K, Harreiter J, Hoermann G, Kautzky-Willer A. Lipoprotein (a) is not related to markers of insulin resistance in pregnancy. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013;12:138. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-12-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manten GT, Voorbij HA, Hameeteman TM, Visser GH, Franx A. Lipoprotein (a) in pregnancy: A critical review of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;122:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fanshawe AE, Ibrahim M. The current status of lipoprotein (a) in pregnancy: A literature review. J Cardiol. 2013;61:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumakura H, Fujita K, Kanai H, Araki Y, Hojo Y, Kasama S. et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive Protein, Lipoprotein (a) and Homocysteine are Risk Factors for Coronary Artery Disease in Japanese Patients with Peripheral Arterial Disease. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2015;22:344–54. doi: 10.5551/jat.25478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Işildak MY, Yildirmak ST, Doğan S, Çakmak M, Özakin E. Serum Homocysteine and Lipoprotein (a) Levels in Preeclamptic Pregnants. Trak Univ Tip Fak De. 2009;26:208. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(98)00527-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baños-González MA, Anglés-Cano E, Cardoso-Saldaña G, Peña-Duque MA, Martínez-Ríos MA, Valente-Acosta B. et al. Lipoprotein (a) and homocysteine potentiate the risk of coronary artery disease in male subjects. Circ J. 2011;76:1953–7. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-12-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baños-González M, Peña-Duque M, Anglés-Cano E, Martinez-Rios M, Bahena A, Valente-Acosta B. et al. Apo (a) phenotyping and long-term prognosis for coronary artery disease. CLB. 2010;43:640–4. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghorbanihaghjo A, Javadzadeh A, Argani H, Nezami N, Rashtchizadeh N, Rafeey M. et al. Lipoprotein (a), homocysteine, and retinal arteriosclerosis. Mol Vis. 2008;14:1692. doi: 10.1007/s00726-012-1321-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinheiro M, Gomes K, Dusse L. Fibrinolytic system in preeclampsia. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;416:67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Úbeda N, Reyes L, González-Medina A, Alonso-Aperte E, Varela-Moreiras G. Physiologic changes in homocysteine metabolism in pregnancy: a longitudinal study in Spain. Nutrition. 2011;27:925–30. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naruszewicz M, Klinke M, Dziewanowski K, Staniewicz A, Bukowska H. Homocysteine, fibrinogen, and lipoprotein (a) levels are simultaneously reduced in patients with chronic renal failure treated with folic acid, pyridoxine, and cyanocobalamin. Metabolism. 2001;50:131–4. doi: 10.1053/meta.2001.20174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanderjagt DJ, Patel RJ, El‐Nafaty AU, Melah GS, Crossey MJ, Glew RH. High-density lipoprotein and homocysteine levels correlate inversely in preeclamptic women in northern Nigeria. Acta Obstet Gynecol. 2004;83:536–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2004.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wen SW, Chen X-K, Rodger M, Rennicks White R, Yang Q, Smith GN. et al. Folic acid supplementation in early second trimester and the risk of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:45. e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manizheh SM, Mandana S, Hassan A, Amir GH, Mahlisha KS, Morteza G. Comparison study on the effect of prenatal administration of high dose and low dose folic acid. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:88–97. doi: 10.1002/14651858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papadopoulou E, Stratakis N, Roumeliotaki T, Sarri K, Merlo DF, Kogevinas M. et al. The effect of high doses of folic acid and iron supplementation in early-to-mid pregnancy on prematurity and fetal growth retardation: the mother–child cohort study in Crete, Greece (Rhea study) Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;52:327–36. doi: 10.1007/s00394-012-0339-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDowell W. Oral folate enhances endothelial function in hyperhomocysteinaemic subjects. Eur J Clin Invest. 1999;29:659–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1999.00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adank C, Green TJ, Skeaff CM, Briars B. Weekly high-dose folic acid supplementation is effective in lowering serum homocysteine concentrations in women. Ann Nutr Metab. 2003;47:55–9. doi: 10.1159/000069278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Z, Ye R, Zhang L, Li H, Liu J, Ren A. Folic acid supplementation during early pregnancy and the risk of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2013;61:873–9. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernandez M, Fernandez G, Diez-Ewald M, Torres E, Vizcaíno G, Fernández N. et al. [Plasma homocysteine concentration and its relationship with the development of preeclampsia Effect of prenatal administration of folic acid] Invest Clin. 2005;46:187–95. doi: 10.1007/s00404-006-0223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sattar N, Clark P, Greer IA, Shepherd J, Packard CJ. Lipoprotein (a) levels in normal pregnancy and in pregnancy complicated with pre-eclampsia. Atherosclerosis. 2000;148:407–11. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parvin S, Samsuddin L, Ali A, Chowdhury SA, Siddique I. Lipoprotein (a) level in pre-eclampsia patients. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 2010;36:97–9. doi: 10.3329/bmrcb.v36i3.7289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mori M, Mori A, Saburi Y, Sida M, Ohta H. Levels of lipoprotein (a) in normal and compromised pregnancy. J Perinat Med. 2003;31:23–8. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2003.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baksu B, Baksu A, Davas I, Akyol A, Gülbaba G. Lipoprotein (a) levels in women with pre‐eclampsia and in normotensive pregnant women. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2005;31:277–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2005.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harpel PC, Chang VT, Borth W. Homocysteine and other sulfhydryl compounds enhance the binding of lipoprotein (a) to fibrin: a potential biochemical link between thrombosis, atherogenesis, and sulfhydryl compound metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:10193–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hustad S, Midttun Ø, Schneede J, Vollset SE, Grotmol T, Ueland PM. The methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase 677C→ T polymorphism as a modulator of a B vitamin network with major effects on homocysteine metabolism. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:846–55. doi: 10.1086/513520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qin X, Li J, Cui Y, Liu Z, Zhao Z, Ge J. et al. MTHFR C677T and MTR A2756G polymorphisms and the homocysteine lowering efficacy of different doses of folic acid in hypertensive Chinese adults. Heart-London. 2012;98:E130. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-11-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelen WL, Blom HJ, Thomas CM, Steegers EA, Boers GH, Eskes TK. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphism affects the change in homocysteine and folate concentrations resulting from low dose folic acid supplementation in women with unexplained recurrent miscarriages. J Nutr. 1998;128:1336–41. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.8.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashfield-Watt PA, Pullin CH, Whiting JM, Clark ZE, Moat SJ, Newcombe RG. et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase 677C→ T genotype modulates homocysteine responses to a folate-rich diet or a low-dose folic acid supplement: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:180–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.1.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams C, Kingwell BA, Burke K, McPherson J, Dart AM. Folic acid supplementation for 3 wk reduces pulse pressure and large artery stiffness independent of MTHFR genotype. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:26–31. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ho GY-H, Eikelboom JW, Hankey GJ, Wong C-R, Tan S-L, Chan JB-C. et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphisms and homocysteine-lowering effect of vitamin therapy in Singaporean stroke patients. Stroke. 2006;37:456–60. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000199845.27512.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moat SJ, Ashfield-Watt PA, Powers HJ, Newcombe RG, McDowell IF. Effect of riboflavin status on the homocysteine-lowering effect of folate in relation to the MTHFR (C677T) genotype. Clin Chem. 2003;49:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]