Abstract

Objectives

To identify distinct sets of disability trajectories in the year before and after a Q-SNF admission, evaluate the associations between the pre- and post-Q-SNF disability trajectories, and determine short-term outcomes (readmission, mortality).

Design, setting and participants

Prospective cohort study including 754 community-dwelling older persons, 70+ years, and initially nondisabled in their basic activities of daily living. The analytic sample included 394 persons, with a first hospitalization followed by a Q-SNF admission between 1998–2012.

Main outcomes and measures

Disability in the year before and after a Q-SNF admission using 13 basic, instrumental and mobility activities. Secondary outcomes included 30-day readmission and 12-month mortality.

Results

The mean (SD) age of the sample was 84.9(5.5) years. We identified three disability trajectories in the year before a Q-SNF admission: minimal disability (37.3% of participants) mild disability (44.6%), and moderate disability (18.2%). In the year after a Q-SNF admission, all participants started with moderate to severe disability scores. Three disability trajectories were identified: substantial improvement (26.0% of participants), minimal improvement (36.5%), and no improvement (37.5%). Among participants with minimal disability pre-Q-SNF, 52% demonstrated substantial improvement; the other 48% demonstrated minimal improvement (32%) or no improvement (16%) and remained moderately to severely disabled in the year post-Q-SNF. Among participants with mild disability pre-Q-SNF, 5% showed substantial improvement, whereas 95% showed little to no improvement. Of participants with moderate disability pre-Q-SNF, 15% remained moderately disabled showing little improvement, whereas 85% showed no improvement. Participants who transitioned from minimal disability pre-Q-SNF to no improvement post-Q-SNF had the highest rates of 30-day readmission and 12-month mortality (rate/100 person days 1.3 [95% CI 0.6–2.8] and 0.3 [95% CI 0.15–0.45], respectively).

Conclusions

Among older persons, distinct disability trajectories were observed in the year before and after a Q-SNF admission. The likelihood of improvement in disability was greatly constrained by the pre-Q-SNF disability trajectory. The majority of older persons remained moderately to severely disabled in the year following a Q-SNF admission.

Background

Hospitalization is a leading cause of long-term disability, defined as disability that lasts for more than six months (1). The incidence of new disability associated with hospitalization ranges from 5–50% (2–4). In general, patients with elective procedures have better disability outcomes than those who are acutely hospitalized. The development of new disabilities during hospitalization is associated with higher health care utilization (5), mortality (3, 6, 7) and institutionalization (8, 9).

Many older patients receive post-acute rehabilitation care after a hospital stay, with the goal of reversing newly acquired disabilities. This post-acute rehabilitation care can be provided in an inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF), skilled nursing facility (SNF), or through a home health agency (HHA). The majority of older persons who are not discharged home receive their rehabilitation care in a SNF. Yearly, Medicare spends more than $30 billion on SNF care, equivalent to 11% of the annual Medicare budget (10). Currently, there are many open questions about the selection of patients who might benefit from post-acute care in an SNF (11), the complexity of regulations to qualify for an SNF stay (12), and outcomes of post-acute care in terms of recovery from disabilities (13).

Little is known, for example, about trajectories of disability before and after a hospitalization leading to an SNF admission. While multiple large studies have evaluated outcomes of SNF care using the Minimum Data Set or Medicare Claims data (14, 15), information has not been available on pre-hospital level of functioning, and prior studies have had relatively long follow-up intervals (e.g. three to six months) (14, 16). Moreover, most prior studies primarily have focused on stroke or hip fracture (17–19). It also remains unknown if receipt of rehabilitation care differs based on pre- and post-hospitalization disability trajectories and if disability trajectories influence the rates of hospital readmission and mortality.

In this study, we set out to identify distinct sets of disability trajectories in the year before and after hospitalization leading to a skilled nursing facility admission, hereafter referred to as a Medicare qualifying SNF admission (Q-SNF); evaluate the relationship between the pre- and post- Q-SNF- disability trajectories; describe the rehabilitation care older persons were projected to receive at admission to the SNF and determine the rates of 30-day hospital readmission, and 12-month mortality using the combinations of pre- and post-Q-SNF disability trajectories.

Methods

Study population

Participants were drawn from the Precipitating Events Project (PEP), a longitudinal study of 754 community-living persons aged 70 years or older who were initially non-disabled in four basic activities of daily living (ADL: bathing, dressing, walking inside the house and transferring from a chair). The assembly of the cohort, which took place between March 1998 and October 1999, has been described in detail elsewhere (20, 21). Only 4.6% of the 2,573 health plan members who were alive and could be contacted refused to complete the telephone interview, and 75.2% of those found to be eligible agreed to participate in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Yale Human Investigation Committee, and all participants provided verbal informed consent.

Data collection

A comprehensive, in-home assessment was conducted at baseline and subsequently at 18-month time intervals for 162 months (with the exception of 126 months). Telephone interviews were completed monthly through 2012, with a completion rate of over 99%. For participants with significant cognitive impairment, the monthly interviews and relevant parts of the comprehensive assessment were completed with a designated proxy. Deaths were ascertained by review of local obituaries and/or from an informant during a subsequent telephone interview, with a completion rate of 100% (1).

Comprehensive assessment

During the comprehensive assessment, data were collected on demographic characteristics, including age, gender, race (Non-Hispanic white versus other), educational status, current marital status, and living situation (alone versus with others). Physician-diagnosed chronic conditions, assessed by self-report, included hypertension, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, diabetes mellitus, arthritis, hip fracture, chronic lung disease, and cancer. Physical frailty was defined as a time of more than 10 seconds on the rapid gait test (i.e., walk 10 feet forward and 10 feet back) (22). Cognitive status was assessed with the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (23). Based on the number of correct responses, the MMSE provides a total score, ranging from 0 to 30, with a score < 24 denoting cognitive impairment. Depressive symptoms were assessed by the 11-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale (24). Scores for this shortened version were transformed to correspond to the standard 20-item scale; and a score of ≥ 20 denoted depressive symptoms.

Assessment of disability

Disability was assessed during the monthly interviews, and included four basic ADLs (bathing, dressing, walking and transferring), five Instrumental ADLs (shopping, housework, meal preparation, taking medication and managing finances), and three mobility tasks (walk quarter a mile, climb a flight of stairs, and lift/carry 10 lb). Participants were asked if they needed help with the specific task at the “present time”. If they needed help, or were not able to perform the task, they were scored as having disability in the specific item. Participants were also asked about a fourth mobility task, ‘Have you driven a car during the past month?’ Participants who responded “no” were deemed to have stopped driving. Possible disability scores ranged from 0 to 13, with a score of 0 indicating complete independence in all of the items, and a score of 13 indicating complete dependence.

Ascertainment of a qualifying SNF admission

For the majority of the sample (91%), we used linkages to Medicare claims data, to identify participants with a qualifying SNF admission. For a SNF admission to qualify for Medicare coverage, an older person has to be admitted to the hospital for at least three consecutive nights, excluding time spent in observation status or in the Emergency Department, and subsequently admitted to the SNF (25).

For each participant, Medicare claims data were linked to those of the comprehensive assessments and monthly interviews. For 37 participants who were in managed Medicare and did not have claims data on hospitalizations, hospital admissions were ascertained during the monthly telephone interviews and were confirmed by review of medical records.

Acquisition of hospitalization data

For all participants, we collected data on hospital length of stay and whether the hospital admission was acute versus elective. The primary discharge diagnosis was based on ICD-9 coding and derived from the Medicare claims data or medical record review.

Acquisition of data on post-acute rehabilitation care within the SNF

For each SNF admission, we used Medicare data to determine length of stay and the Resource Utilization Group (RUG) at the time of admission (26). The RUG is determined after completion of the Minimum Data Set (MDS) and is based on the number of minutes of rehabilitation needed (physical, occupational or speech therapy), the need for certain services (e.g intravenous therapy, specialized feeding), the presence of certain conditions (e.g pneumonia) and ADL score (26). High concordance between the RUG code and rehabilitation time actually provided has been previously demonstrated (27)

Analytic sample

The analytic sample for the current study included 394 participants with a first Medicare Qualifying Skilled Nursing Facility admission (Q-SNF) (25), from their enrollment in 1998 till 2011, allowing for a year of follow-up for all Q-SNF admissions.

Statistical analysis

Participants were characterized with means and standard deviations for continuous variables and counts with percentages for categorical data. Our primary outcome was the total number of disabilities, with integer values ranging from 0 to 13.

To identify distinct trajectories of disability before and after a Q-SNF admission, we used a form of latent class analysis, called trajectory modeling (28). Specifically, we used the SAS macro (version 9.3), called PROC TRAJ with a censored normal distribution and no covariates. In each of the years immediately before and after the Q-SNF admission, and based on statistical and clinical criteria described elsewhere (29), three trajectories were found to be optimal. The unadjusted monthly least square means of total disability within each trajectory were plotted for the years immediately before and after the Q-SNF admission.

We subsequently repeated the trajectory modeling in the year after Q-SNF admission with adjustment for the following covariates: age, sex, race, educational level less than high school, number of chronic conditions, physical frailty, cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, and type of hospital admission (acute or elective), using covariate values available immediately before (or during) the hospital admission. Using 1000 bootstrapped samples(30), we calculated the non-parametric probability of membership in each post-Q-SNF disability trajectory conditional on membership in a given pre-Q-SNF disability trajectory.

Projected rehabilitation time, based on the RUG code, was classified as: low (45–149 minutes), medium (150–324 minutes), high (325–499), very high (500–719) and ultra-high (more than 720 minutes). Patients in need of less than 45 minutes of therapy were classified as no rehabilitation. The projected rehabilitation was plotted for the combined pre-and post-Q-SNF disability trajectories.

For each of combined pre- and post-Q-SNF-trajectories, we also calculated the rates per 100 person-days (95% CIs) of 30-day hospital readmissions, and 12-month mortality using a Poisson regression model.

All analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.3), and differences were considered statistically significant at P < .05 (2-tailed); figures were made using Graphpad or Microsoft Excel.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Among all participants, the mean age at the time of hospital admission was 84.9 years; the majority of participants were female and white (Table 1). Prior to their hospital admission, 70.8% of participants had physical frailty, 25.6% had cognitive impairment and 23.6% had depressive symptoms. Twelve months before hospitalization, the median number of disabilities was 3 (IQR 1–6). More than 80% of the hospital admissions were non-elective. The most prevalent discharge diagnoses were infection (16.8%), fracture (14.2%), musculoskeletal disorder (12.2%) and cardiac disease (12.2%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 394 participants according to pre-Q-SNF disability trajectory

| Characteristics | All participants N=394 | Minimal disability N=147 | Mild disability N=176 | Moderate disability N=71 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| At the time of hospitalization | ||||

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 84.9 (5.5) | 82.8 (4.9) | 84.3 (5.6) | 87.6 (5.1) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 267 (67.8) | 93 (63.1) | 116 (66.1) | 58 (79.7) |

| Non-Hispanic white, n (%) | 356 (90.4) | 134 (91.5) | 157 (88.9) | 65 (91.3) |

| Did not complete high school, n (%) | 145 (36.8) | 34 (22.7) | 69 (38.6) | 42 (58.0) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||

| Married | 162 (41.1) | 52 (35.5) | 81 (46.2) | 29 (40.6) |

| Separated/divorced/never married | 44 (11.2) | 16 (10.6) | 21 (12.3) | 7 (10.1) |

| Widowed | 188 (47.7) | 79 (53.9) | 74 (41.5) | 35 (49.3) |

| Living alone, n (%) | 190 (48.2) | 88 (59.6) | 71 (40.4) | 31 (42.0) |

| Number of disabilities, median (IQR) | ||||

| 12 months before hospital admission | 3 (1–6) | 1 (0–2) | 4 (3–6) | 8 (7–11) |

| 1 month before hospital admission | 6 (2–9) | 2 (1–3) | 6 (5–8) | 10 (10–12) |

| In-home assessment prior to hospital admission | ||||

| Multimorbidity*, n (%) | 287 (72.8) | 92 (62.4) | 133 (75.4) | 60 (84.1) |

| Physical frailty †, n (%) | 279 (70.8) | 69 (46.8) | 142 (80.1) | 68 (95.7) |

| Cognitive impairment ‡, n (%) | 101 (25.6) | 15 (9.9) | 42 (23.4) | 30 (42.0) |

| Depressive symptoms §, n (%) | 93 (23.6) | 25 (17.7) | 45 (26.3) | 19 (27.5) |

| Hospital admission characteristics | ||||

| Type of admission, n (%) | ||||

| Acute | 322 (81.9) | 104 (70.2) | 149 (84.2) | 69 (97.1) |

| Elective | 71 (18.1) | 42 (29.8) | 27 (15.8) | 2 (2.9) |

| Primary discharge diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| Infection (including pneumonia) | 66 (16.8) | 13 (8.5) | 31 (18.2) | 22 (30.4) |

| Fracture (including hip fracture) | 56 (14.2) | 26 (18.4) | 20 (11.7) | 10 (14.5) |

| Musculoskeletal | 48 (12.2) | 28 (19.9) | 20 (11.1) | 1 (1.4) |

| Cardiac | 48 (12.2) | 17 (11.3) | 23 (12.9) | 8 (10.1) |

| Stroke | 23 (5.8) | 8 (5.0) | 10 (5.8) | 5 (7.2) |

| Cancer | 23 (5.8) | 15 (9.9) | 6 (3.5) | 2 (1.4) |

| Gastrointestinal | 22 (5.6) | 8 (5.0) | 12 (7.6) | 2 (2.9) |

| Respiratory (incl COPD) | 19 (4.8) | 4 (2.8) | 6 (3.5) | 6 (8.6) |

| Vascular | 17 (4.3) | 5 (3.5) | 10 (5.8) | 2 (2.9) |

| Neurodegenerative disease | 15 (3.8) | 5 (3.5) | 9 (5.3) | 1 (1.4) |

| Other medical ± | 57 (14.5) | 18 (12.0) | 26 (14.8) | 13 (18.6) |

All participants had a qualifying skilled nursing facility admission. To qualify for a SNF stay an older person must have been admitted to the hospital for at least three consecutive nights, and admitted to the SNF within 30-days after hospital discharge

defined as 2 or more chronic conditions;

operationalized as slow gait speed based on 10 feet forward and 10 feet back walking test;

defined as Mini-mental State Score of <24;

defined as Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale ≥ 20

includes renal failure, diabetes, dehydration, anemia (among others)

Disability trajectories before and after Q-SNF admission

In the year preceding the Q-SNF admission, three distinct disability trajectories were identified: 37.3% of participants had minimal disability, 44.6% had mild disability, and 18.2% had moderate disability (Figure 1, Panel A). As they approached the Q-SNF-admission, all three groups had trajectories of worsening disability. Compared with participants in the minimal and mild disability groups, participants in the moderate disability group were older, were more likely to have multimorbidity, physical frailty, cognitive impairment, an acute hospital admission, and a discharge diagnosis of infection (Table 1).

Figure 1. Disability trajectories before (A) and after (B) a Q-SNF admission.

Number and percentage of participants for each trajectory are shown in parentheses. The number of disabilities ranged from 0 to 13 based on 4 basic activities (bathing, dressing, walking inside the house, and transferring from a chair), 5 instrumental activities (shopping, housework, meal preparation, taking medications, and managing finances), and 4 mobility activities (walking a quarter mile, climbing a flight of stairs, lifting or carrying 10 lb, and driving). Solid lines indicate observed trajectories; dashed lines indicate predicted trajectories. The error bars represent 95% CIs for the predicted severity of disability. The dual model was adjusted for age, sex, race, educational level less than high school, number of chronic conditions, physical frailty, cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms and acute admission, using information available just before or at the time of hospital admission. Panel 1A and 1B are interconnected; Of the participants with minimal disability before the pre-Q-SNF admission (n=147) 52% (n=83) transitioned to substantial improvement, 32% (n=38) to little improvement and 16% (n=20) to no improvement.

Three distinct post-Q-SNF disability trajectories were identified (Figure 1, Panel B): 26.0% of the participants had substantial improvement, going from moderate disability following hospital discharge (mean 7.4, 95% CI 6.9–8.0) to minimal disability at 1-year (mean 2.3, 95% CI 2.0–2.6); 36.5% showed modest improvement, going from severe disability at hospital discharge (mean 10.8, 95%CI 10.2–11.3) to moderate disability at 1 year (mean 8.3, 95% CI 7.7–8.9); and 37.5% demonstrated no improvement, remaining severely disabled throughout the 12-month follow-up period. Improvements in disability were only observed in the first six-months.

Transition probabilities from pre- to post-Q-SNF disability trajectories

Table 2 lists the adjusted probabilities of the post-Q-SNF trajectories conditional on the pre-Q-SNF trajectories. Among participants with minimal disability prior to their Q-SNF admission, 52% demonstrated substantial improvement, 32% showed little improvement and 16% showed no improvement. Of the group with mild disability prior to their Q-SNF admission, only 5% showed substantial improvement, 56% demonstrated little improvement, while 38% showed no improvement. Of the group with moderate disability prior to their Q-SNF admission, 15% demonstrated little improvement, while 85% worsened to severe disability.

Table 2.

Adjusted probabilities (95% confidence intervals) of transitioning between preand post-Q-SNF trajectories

| Post-Q-SNF trajectory | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Q-SNF trajectory | Substantial improvement | Little improvement | No improvement |

| Minimal disability | 0.52 (0.46–0.70) (n=83) | 0.32 (0.19–0.39) (n=38) | 0.16 (0.03–0.23) (n=20) |

| Mild disability | 0.05 (0.03–0.22) (n=16) | 0.56 (0.39–0.70) (n=89) | 0.38 (0.19–0.53) (n=66) |

| Moderate disability | 0.00 | 0.15 (0.00–0.47) (n=12) | 0.85 (0.53–1.00) (n=57) |

The model was adjusted age, sex, race, educational level less than high school, number of chronic conditions, physical frailty, cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, and type of hospital admission (acute or elective), based on information available immediately before or during the hospital admission. The probabilities were calculated with Bayes’ rule, and the corresponding 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) were estimated with bootstrapping using 1000- samples. Figure 1 and Table 2 are interconnected. Participants in the substantial improvement group in the post-Q-SNF trajectory (figure 1, panel B) come from those with minimal disability (n=83) and mild disability (n=16) in the pre-Q-SNF trajectory (figure 1, panel A).

Figure 1 and Table 2 are interconnected. Participants in the substantial improvement group in the post-Q-SNF trajectory (figure 1, panel B) come from those with minimal disability (n=83) and mild disability (n=16) in the pre-Q-SNF trajectory (figure 1, panel A).

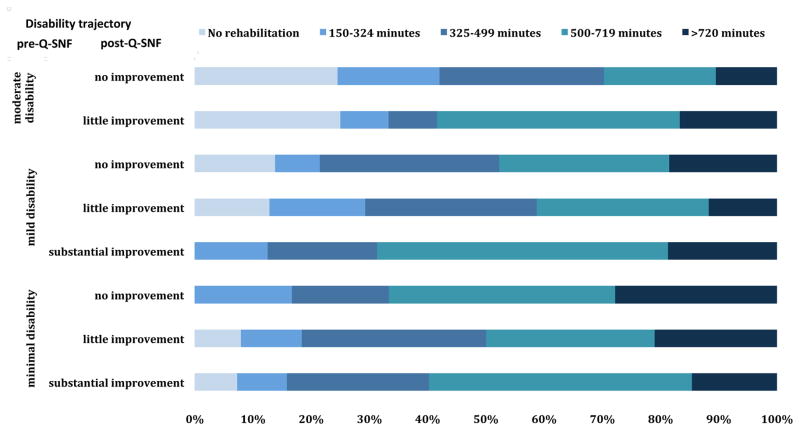

Post-acute rehabilitation care in the SNF

The median length of stay in the SNF was 21 days (IQR 12–42). Figure 2 shows the receipt of rehabilitation care within the SNF for the combined pre- and post-Q-SNF trajectories. The majority of participants were assigned to receive very high (500–719 minutes) to ultra-high (>720 minutes) rehabilitation care, except for participants who were moderately disabled in their pre-Q-SNF trajectory and demonstrated no improvement in their post-Q-SNF trajectory. A small proportion of participants in the minimal disability pre-Q-SNF group (<5%) and mild disability pre-Q-SNF group (<15%) did not receive any rehabilitation, whereas 25% in the moderate disability pre-Q-SNF group did not receive rehabilitation care.

Figure 2. The projected rehabilitation time at admission to the skilled nursing facility by disability trajectory.

Percentages are based on the assigned resource utilization group (RUG) at the time of admission.

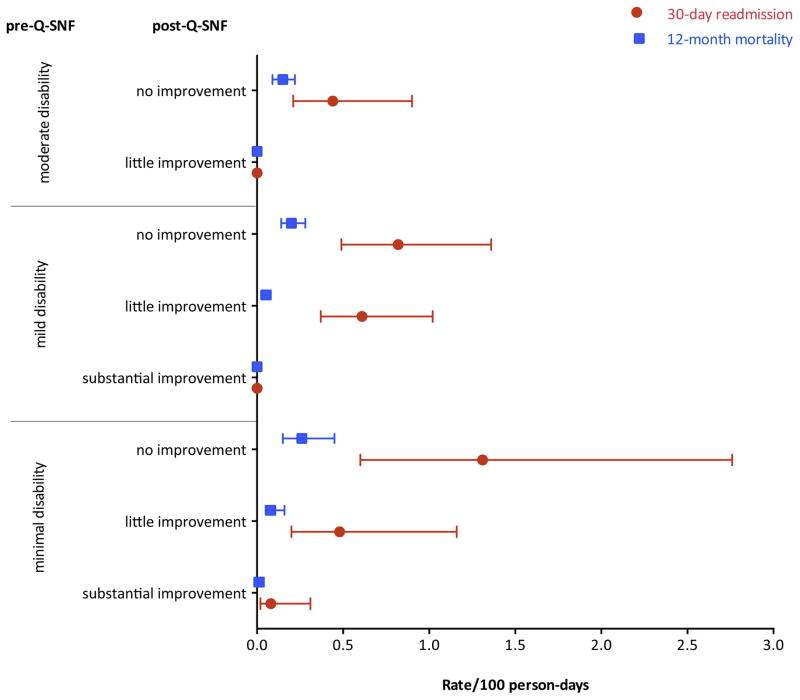

Rates of 30-day readmission and 12-month mortality

Figure 3 provides the rates/100 person-days for 30-day readmission and 12-month mortality for the combined pre- and post-Q-SNF trajectories. Overall, 14.0% of participants had a readmission to the hospital from the SNF within 30-days post-hospital discharge and 26.9% died within 12-months after hospital admission. Rates of 30-day readmission and 12-month mortality were highest in participants who were in the minimal disability group before the Q-SNF admission and transitioned to the no improvement group in the post-Q-SNF trajectory (rate/100 person days 1.3, 95% CI 0.6–2.8, and 0.3, 95% CI 0.15–0.45, respectively).

Figure 3. Rates (95% confidence intervals) per 100 person days for 30-day hospital readmission and 12-month mortality by pre- and post-Q-SNF trajectory.

The bars denote the 95% Confidence intervals.

Discussion

In this study, we identified distinct sets of disability trajectories in older persons before and after a Q-SNF admission and the post-Q-SNF trajectories were strongly linked to the pre-Q-SNF disability trajectories. In the year preceding the pre-Q-SNF admission, the severity of disability slightly increased for each of the trajectories, and only 18% of participants were in the moderate disability group. In contrast, at the start of the post-Q-SNF-trajectory, all participants had moderate to severe disability scores. In the year following the Q-SNF admission, substantial improvements were observed in only half of the minimal disability group and five percent of the mild disability group. All other participants demonstrated little to no improvements in the following year and remained moderately or severely disabled. Improvements in functioning were observed only during the first six months in the post-Q-SNF trajectory. Thereafter, disability trajectories remained stable or slightly increased again. Most participants were assigned to receive more than 500 minutes of rehabilitation care at admission to the SNF, except for participants with moderate disability in the pre-Q-SNF-trajectory; one-quarter of this group did not receive rehabilitation care. The rates of 30-day readmission and 12-month mortality were highest in older persons who transitioned from minimal disability in the pre-Q-SNF trajectory to no improvement with severe disability in the post-Q-SNF disability trajectory.

It is well described that a hospital admission is strongly associated with long-term disability (1, 31); rates of hospitalization-associated disability vary between 15–50% (2, 3). Newly acquired disabilities are difficult to recover (32). We found that the probabilities of the post-Q-SNF trajectories were strongly linked to the pre-Q-SNF disability trajectories. Participants with mild or moderate disability were less likely than those with minimal disability to show improvements in functioning in the post-Q-SNF trajectory. The groups with mild or moderate disability were older and had a higher prevalence of physical frailty and cognitive impairment than participants in the minimal disability group. Old age, physical frailty and cognitive impairment are all known predictors of post-hospitalization disability (33).

A higher percentage of participants with moderate disability before the Q-SNF admission did not receive any rehabilitation at admission to the SNF compared with other pre-Q-SNF trajectories. This group more often only needed nursing care. Based on their high level of disability in the year before admission and presence of cognitive impairment, this group had less potential to recover from new disabilities (15, 34). However, independent of pre- and post-Q-SNF trajectory, more than one-third of participants received more than 500 minutes of rehabilitation care (physical therapy, occupational therapy or speech-language therapy). This could be explained by the fact that ADL functioning at the time of admission to the SNF determines the number of minutes of therapy an older person receives within the SNF. As demonstrated, all participants had high levels of disability at admission to the SNF.

Participants who transitioned from minimal disability in the pre-Q-SNF trajectory to no improvement in the year after a Q- SNF admission had the highest 30-day hospital readmission rates and 12-month mortality rates. Previous studies have demonstrated that higher ADL score, cognitive impairment and higher age at the time of admission are associated with both outcomes (3, 35). The study of Kruse et al in nursing home residents that were hospitalized and subsequently discharged to the SNF also found high levels of 30- day mortality in participants with worsening disability trajectories, but not higher levels of 30-day readmission (15). We hypothesize that the hospitalization and illness underlying the hospitalization were so severe, resulting in a large ADL decline, that it made these participants also more vulnerable for other adverse outcomes, such as readmission and mortality.

The availability of monthly data on disability in the year before and after the Q-SNF admission is a novel feature of our study. It enabled us to characterize detailed disability trajectories in the year before and after a Q-SNF admission, data that are lacking in most studies. Moreover, we were able to link self-reported data on ADLs to Medicare claims data on hospitalization and rehabilitation. This allowed us to describe rehabilitation care and readmission and mortality outcomes using by joined disability trajectories.

Our study results should be interpreted in the context of some limitations. First, our study was carried out in the State of Connecticut. The availability of SNF beds in Connecticut is higher than that of some other states (36), and it is known that higher availability of SNF beds results in more discharges to a SNF (37). However, previous research demonstrated that Connecticut had nationwide comparable hospital readmission rates from the SNF for post-acute care (38). Moreover, data were not available on the rehabilitation that was actually received, and we also do not know if rehabilitation guidelines were followed, or if rehabilitation was the actual goal of the SNF admission. We had information about the projected rehabilitation time based on the RUGs, and prior work has showed a strong association between the RUG and the actual minutes of therapy received (27, 39).

In conclusion, we identified distinct disability trajectories in the year before and after a Q-SNF admission, and demonstrated that these trajectories were highly interconnected. In the year after the Q-SNF admission, the majority of patients demonstrate moderate to severe disability, and show little to no improvement. Participants who transition to a worse disability trajectory had the highest rates of 30-day readmission and 12-month mortality. Our results indicate that many older persons end up with new disabilities in the year after a Q-SNF admission. More research is needed to identify factors that contribute to recovery in persons discharged to a SNF, and to identify the effectiveness of rehabilitation interventions in older persons in different rehabilitation settings and in different health care systems. The results of our study could inform discussions on the desired outcomes after post-acute care admission to a SNF and how to further work on care strategies that enhance these desired outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank, Denise Shepard, BSN, MBA, Andrea Benjamin, BSN, Barbara Foster, and Amy Shelton, MPH for assistance with data collection; Wanda Carr and Geraldine Hawthorne, BS, for assistance with data entry and management; Peter Charpentier, MPH for design and development of the study database and participant tracking system; and Joanne McGloin, MDiv, MBA for leadership and advice as the Project Director.

Funding/Support:

The work for this report was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging (R37AG17560, R01AG022993). The study was conducted at the Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30AG21342). Dr. Buurman is supported by a Rubicon grant (825.12.022) from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research (NWO). Dr. Gill is the recipient of an Academic Leadership Award (K07AG043587) from the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

Drs. Buurman and Gill had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The specific contributions are enumerated in the authorship, financial disclosure, and copyright transfer form.

Role of the Sponsors:

The organizations funding this study had no role in the design or conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gill TM, Allore HG, Gahbauer EA, Murphy TE. Change in disability after hospitalization or restricted activity in older persons. JAMA. 2010;304(17):1919–28. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyd CM, Landefeld CS, Counsell SR, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, Kresevic D, et al. Recovery of activities of daily living in older adults after hospitalization for acute medical illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(12):2171–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02023.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buurman BM, Hoogerduijn JG, de Haan RJ, Abu-Hanna A, Lagaay AM, Verhaar HJ, et al. Geriatric conditions in acutely hospitalized older patients: prevalence and one-year survival and functional decline. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e26951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoogerduijn JG, Buurman BM, Korevaar JC, Grobbee DE, de Rooij SE, Schuurmans MJ. The prediction of functional decline in older hospitalized patients. Age Ageing. 2012 doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Williams CS, Tinetti ME. Functional disability and health care expenditures for older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(21):2602–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.21.2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drame M, Jovenin N, Novella JL, Lang PO, Somme D, Laniece I, et al. Predicting early mortality among elderly patients hospitalised in medical wards via emergency department: the SAFES cohort study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12(8):599–604. doi: 10.1007/BF02983207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walter LC, Brand RJ, Counsell SR, Palmer RM, Landefeld CS, Fortinsky RH, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic index for 1-year mortality in older adults after hospitalization 5. JAMA. 2001;285(23):2987–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.23.2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luppa M, Luck T, Weyerer S, Konig HH, Brahler E, Riedel-Heller SG. Prediction of institutionalization in the elderly. A systematic review. Age Ageing. 2010;39(1):31–8. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Portegijs E, Buurman BM, Essink-Bot ML, Zwinderman AH, de Rooij SE. Failure to Regain Function at 3 months After Acute Hospital Admission Predicts Institutionalization Within 12 Months in Older Patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MedPac 2013;Pages2013.

- 11.Mechanic R. Post-acute care--the next frontier for controlling Medicare spending. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):692–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1315607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipsitz LA. The 3-night hospital stay and Medicare coverage for skilled nursing care. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1441–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.254845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ackerly DC, Grabowski DC. Post-acute care reform--beyond the ACA. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):689–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1315350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen LA, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Curtis LH, Dai D, Masoudi FA, et al. Discharge to a skilled nursing facility and subsequent clinical outcomes among older patients hospitalized for heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4(3):293–300. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.959171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kruse RL, Petroski GF, Mehr DR, Banaszak-Holl J, Intrator O. Activity of daily living trajectories surrounding acute hospitalization of long-stay nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(11):1909–18. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buntin MB, Colla CH, Deb P, Sood N, Escarce JJ. Medicare spending and outcomes after postacute care for stroke and hip fracture. Med Care. 2010;48(9):776–84. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e359df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prvu Bettger JA, Stineman MG. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary rehabilitation services in postacute care: state-of-the-science. A review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(11):1526–34. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.06.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Ku LJ. Postacute rehabilitation care for hip fracture: who gets the most care? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):1929–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mallinson T, Deutsch A, Bateman J, Tseng HY, Manheim L, Almagor O, et al. Comparison of discharge functional status after rehabilitation in skilled nursing, home health, and medical rehabilitation settings for patients after hip fracture repair. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(2):209–17. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gill TM, Desai MM, Gahbauer EA, Holford TR, Williams CS. Restricted activity among community-living older persons: incidence, precipitants, and health care utilization. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(5):313–21. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-5-200109040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardy SE, Gill TM. Recovery from disability among community-dwelling older persons. JAMA. 2004;291(13):1596–602. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Allore HG, Han L. Transitions between frailty states among community-living older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(4):418–23. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) depression symptoms index. J Aging Health. 1993;5(2):179–93. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Services CfMaM; Services CfMaM, editor. Chapter 8 Coverage of Extended Care (SNF) Services under Hospital Insurance. Washington DC: 2014. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fries BE, Cooney LM., Jr Resource utilization groups. A patient classification system for long-term care. Med Care. 1985;23(2):110–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Care IFfM. Staff Time and Resource Intensity Verification Project Phase II. Michigan: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muthen B. Latent variable analysis: growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. In: Kaplan D, editor. The Sage handbook of quantitative methodology for the social sciences. Thousand Oakes, CA: Sage Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gill TM, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, Allore HG. The course of disability before and after a serious fall injury. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(19):1780–6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. New York: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston CB. Hospitalization-associated disability: “She was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure”. JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ettinger WH. Can hospitalization-associated disability be prevented? JAMA. 2011;306(16):1800–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoogerduijn JG, Schuurmans MJ, Duijnstee MS, de Rooij SE, Grypdonck MF. A systematic review of predictors and screening instruments to identify older hospitalized patients at risk for functional decline. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(1):46–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Han L, Allore HG. Factors associated with recovery of prehospital function among older persons admitted to a nursing home with disability after an acute hospitalization. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(12):1296–303. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, Kagen D, Theobald C, Freeman M, et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA. 2011;306(15):1688–98. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Medicaid CfM. CMS Nursing Home Data Compendium 2012. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buntin MB, Garten AD, Paddock S, Saliba D, Totten M, Escarce JJ. How much is postacute care use affected by its availability? Health Serv Res. 2005;40(2):413–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00365.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Grabowski DC. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(1):57–64. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fries BE, Schneider DP, Foley WJ, Gavazzi M, Burke R, Cornelius E. Refining a case-mix measure for nursing homes: Resource Utilization Groups (RUG-III) Med Care. 1994;32(7):668–85. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199407000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]