Abstract

Objective

To examine fall risk trajectories occurring naturally in a sample of individuals with early to middle stage Parkinson’s disease (PD).

Design

Latent class analysis, specifically growth mixture modeling (GMM) of longitudinal fall risk trajectories.

Setting

Not applicable.

Participants

230 community-dwelling PD participants of a longitudinal cohort study who attended at least two of five assessments over a two year period.

Interventions

Not applicable.

Main Outcome Measures

Fall risk trajectory (low, medium or high risk) and stability of fall risk trajectory (stable or fluctuating). Fall risk was determined at 6-monthly intervals using a simple clinical tool based on fall history, freezing of gait, and gait speed.

Results

The GMM optimally grouped participants into three fall risk trajectories that closely mirrored baseline fall risk status (p=.001). The high fall risk trajectory was most common (42.6%) and included participants with longer and more severe disease and with higher postural instability and gait disability (PIGD) scores than the low and medium risk trajectories (p<.001). Fluctuating fall risk (posterior probability <0.8 of belonging to any trajectory) was found in only 22.6% of the sample, most commonly among individuals who were transitioning to PIGD predominance.

Conclusions

Regardless of their baseline characteristics, most participants had clear and stable fall risk trajectories over two years. Further investigation is required to determine whether interventions to improve gait and balance may improve fall risk trajectories in people with PD.

Keywords: Parkinson disease, accidental falls, risk, longitudinal studies, gait

Falls are a disabling and problematic occurrence for people with Parkinson’s disease (PD). Falls occur in 45–68% of the PD population annually,1 a rate double that of the general older population.2 Falls in people with PD may result in injuries or other adverse consequences, which in turn are associated with prolonged hospitalizations and higher healthcare costs.3

Fall risk in PD is multifactorial, with a positive fall history, history of freezing of gait (FOG), and reduced gait speed identified as among the most potent predictors of a future fall.4 Additionally, the incidence of falls increases with disease progression,1,5 until the point at which individuals become relatively immobile and appear to fall less.6 Nevertheless, the extent to which fall risk in PD might increase without a concurrent change in the level of disease severity, and whether the rate of increase in fall risk might differ according to baseline disease severity, remains unclear. It is also unknown whether fall risk fluctuates during specific periods of disease progression. These questions are relevant, given mixed results about the efficacy of exercise interventions for fall prevention in PD.7–11

Given the progressive neurodegeneration and functional decline associated with PD, knowledge about progression of fall risk over time will assist clinicians to more effectively prevent and manage falls in this population by helping to improve the manner in which fall risk assessment and interventions are employed.1,12 The primary aim of this study, therefore, was to track fall risk longitudinally in people with PD. Secondary aims were to investigate which characteristics differed between the various fall risk trajectories and the characteristics associated with changes in fall risk over time. We hypothesized that over the 2-year follow up period, most participants classified by a clinical tool at baseline as being at high fall risk would remain at high risk, whereas a proportion of those classified by the tool as being at low or medium risk would have increased their fall risk. We further hypothesized that the postural instability and gait disability (PIGD) subtype of PD would be associated with greater progression of fall risk. Individuals with the PIGD subtype have predominantly bilateral and axial symptoms including stooped posture, greater gait and balance impairment, and FOG.13

METHODS

Participants

Community-dwelling individuals aged 40 or over, who had been diagnosed with idiopathic PD by a neurologist, who were in Hoehn and Yahr stages 1–4, and who had Mini-mental State Examination scores ≥24 were eligible for enrolment in a multicentre longitudinal cohort study focusing on the natural history of functional decline and quality of life.14 Exclusion criteria included a diagnosis of atypical parkinsonism or previous surgical intervention for PD (e.g. deep brain stimulation).

Participants were assessed “on” medication at baseline and then every six months for a total of 24 months. Trained physical therapists assessed participants according to a manual of standard operating procedures at one of the following locations: 34 participants at the University of Utah, 71 at Boston University, 66 at Washington University in St. Louis, and 59 at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Potential predictors and outcomes were obtained during each assessment session. Participants continued to receive standard medical care over the two-year study period, including neurology follow-ups and other prescribed medical or allied health interventions.

This study was approved by the ethics committees of all participating sites. All participants provided written informed consent prior to data collection. This study conforms to STROBE reporting guidelines.15

Clinical characteristics

Fall risk at each assessment was determined to be low, medium or high based on a validated16 simple clinical fall prediction tool. Accordingly, weighted scores were assigned for positive fall history in the past year (6 points), positive FOG history in the past month (3 points), and preferred gait speed <1.1 m/s (2 points). Total scores range from 0–11, with 0 indicating low, 2–6 indicating medium, and 8–11 indicating high fall risk.4 Falls were defined as unintentionally coming to rest on the ground or other lower surface without being exposed to overwhelming external force or a major internal event.17 Fall history over the past 6-months was collected at each assessment using a forced-choice paradigm: none, once, 2–10 times, weekly, or daily. History of FOG was determined using Question 3 of the FOG Questionnaire,18 i.e. “Do you feel that your feet get glued to the floor while walking, making a turn or when trying to initiate walking (freezing)?”; scores ≥1 indicated a positive FOG history. Gait speed was determined by averaging the scores from two trials of the 10 meter walk test, which participants completed at their comfortable pace.

Age, gender, time since PD diagnosis, levodopa equivalent dose19 and PD severity according to the motor section (Part 3) of the Movement Disorders Society-sponsored version of the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS)20 were obtained. Tremor dominant, PIGD, and indeterminate PD subtypes were determined using relevant items of Parts 2 and 3 of the MDS-UPDRS according to published criteria.13 Dyskinesias were quantified using the sum of items in Part 4A of the MDS-UPDRS. Physical activity was quantified using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly, for which scores range from 0 to >400 and higher scores indicate higher physical activity levels.21

Data analysis

Latent class analysis, specifically growth mixture modelling (GMM),22 was used to assign groups of participants into a small number of distinct trajectories of fall risk based on participants’ level of fall risk at each assessment ascertained with the clinical tool. GMM, which assumes heterogeneity within a population, obtained the smallest number of latent classes (i.e. trajectories) that accounted for all associations between the biannual fall risk determinations within the 2-year time period by minimising within-class variation and maximising between-class variation.22 This process allowed for the identification of a primary fall risk trajectory for each individual and whether individuals were stable within their trajectory or fluctuated between trajectories. The posterior probability of belonging to each trajectory was obtained for each individual, with participants allocated to the trajectory for which the probability was the largest.

The GMM was fitted successively, starting with a one-latent class model that assumed all participants had the same progression of fall risk over time. The optimal number of trajectories subsequently was determined by examining the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), the Lo-Mendel-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test (LMR-LRT) and the Bootstrapped Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT).23 Although participants did not need to have complete data (i.e. data for each assessment) to be included in a GMM, we recognized that missing data could influence goodness-of-fit tests. Therefore, the first analysis assessed the optimal solution with participants having complete data. The analysis was then rerun by including participants with data from at least two assessments and compared to those having complete data (i.e. from all five assessments). Monte Carlo GMM simulations suggest a sample size of 125 is needed for power of 0.86 to reject the hypothesis that the model is misspecified. Parameter and standard error estimates at this sample size appear to have little bias.24

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-square tests were used to describe differences in participant characteristics between baseline and the 2-year time point and between the three fall risk trajectories. ANOVA and chi-square analyses with statistically significant (p<.05) results were followed-up with pair-wise post-hoc comparisons. Bonferroni adjustment was used for all post-hoc comparisons. Data examined with ANOVA were scrutinized for normality, outliers, and homogeneity of variances. T-tests were used to compare characteristics of participants with stable fall risk trajectories (i.e. posterior probabilities ≥0.8) to those with fluctuating fall risk (posterior probabilities <0.8). MPLUS v6.11 (Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles CA) was used to model the GMM and IBM SPSS Statistics v22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk NY) was used for the remaining analyses.

RESULTS

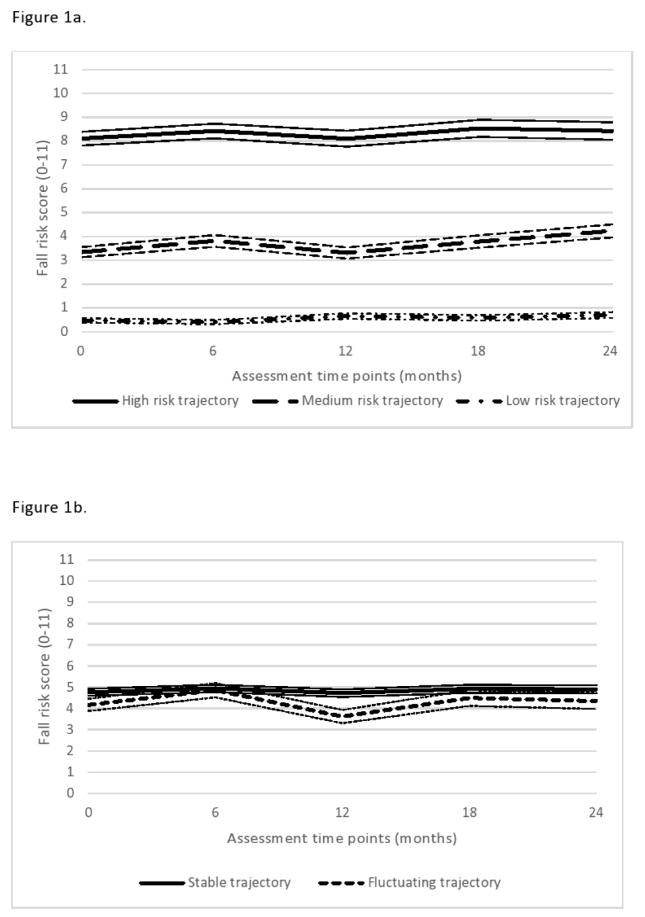

Two hundred and thirty participants with data from at least two assessment points were included in the analysis (Table 1). The GMM optimally grouped participants into three fall risk trajectories (BIC 1681.33 versus 2093.09 for a one-latent class model, LMR-LRT and BLRT p=.001), which closely mirrored baseline fall risk as determined by the fall prediction tool (Figure 1a). Adding a fourth trajectory did not improve model fit from the GMM (BIC 1688.65, LMR-LRT p=.46 and BLRT p=.48). The fall risk trajectories remained the same whether the GMM model included only those participants with complete data (n=124, three-class model: BIC 1077.4, LMR-LRT and BLRT p<.001, versus four-class model: BIC 1090.1, LMR-LRT and BLRT p=.76) or those with at least two assessments (Supplemental).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics stratified by latent class analysis and presented as mean (95% CI) or n (%).

| Variable | N | Analyzed cohort (n=230) | Trajectory 1: High fall risk (n=98) | Trajectory 2: Medium fall risk (n=73) | Trajectory 3: Low fall risk (n=59) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 230 | 67.1 (65.9, 68.3) | 69.5 (67.8, 71.3) | 66.9 (64.8, 69.0) | 63.3 (61.0, 65.6) |

|

| |||||

| Sex (male, female) | 230 | 132 (57.4), 98 (42.6) | 57 (58.2), 41 (41.8) | 42 (57.5), 31 (42.5) | 33 (55.9), 26 (44.1) |

|

| |||||

| Disease duration (years since diagnosis) | 228 | 5.9 (5.3, 6.5) | 8.0 (7.0, 8.9) | 4.4 (3.5, 5.2)1 | 4.2 (3.3, 5.1)1 |

|

| |||||

| MDS-UPDRS-3 (0 to 132) | 229 | 32.2 (30.4,34.0) | 38.2 (35.4, 41.0) | 28.4 (25.7, 31.1)1 | 26.9 (23.7, 30.1)1 |

|

| |||||

| Levodopa equivalent dose (mg/day) | 230 | 559.2 (495.8, 622.5) | 741.8 (633.3, 850.3) | 438.1 (353.3, 522.9)1 | 405.6 (293.3, 517.8)1 |

|

| |||||

| PASE score (0 to >400)† | 229 | 143.4 (132.7, 154.1) | 107.4 (98.4, 120.3) | 166.4 (145.4, 187.5)1 | 175.5 (155.9, 195.0)1 |

|

| |||||

| Fall risk category | 230 | 1 | 1,2 | ||

| High | 76 (33.0) | 71 (72.4) | 4 (5.5) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Med | 79 (34.4) | 25(25.5) | 50 (68.5) | 4 (6.8) | |

| Low | 75 (32.6) | 2 (2.0) | 19 (26.0) | 54 (91.5) | |

|

| |||||

| Fall history | 230 | 1 | 1,2 | ||

| None | 127 (55.2) | 21 (21.4) | 50 (68.5) | 56 (94.9) | |

| One | 51 (22.2) | 31 (31.6) | 17 (23.3) | 3 (5.1) | |

| Multiple | 52 (22.6) | 46 (46.9) | 6 (8.2) | 0 (0) | |

|

| |||||

| Self-paced gait speed (m/s)† | 229 | 1.19 (1.16, 1.23) | 1.08 (1.02, 1.14) | 1.22 (1.17, 1.27)1 | 1.33 (1.29, 1.37)1,2 |

|

| |||||

| FOG severity score (0 to 16) | 230 | 1.3 (1.1, 1.5) | 2.4 (2.1, 2.6) | .9 (.6, 1.2)1 | .1 (0, .2)1,2 |

|

| |||||

| Dyskinesia severity (0 to 8) | 230 | .7 (.5, .8) | 1.1 (.8, 1.4) | .3 (.1, .4)1 | .4 (.2, .7)1 |

|

| |||||

| PIGD score (0 to >1.15) | 229 | .8 (.7, .9) | 1.2 (1.1, 1.4) | .56 (.47, .66)1 | .35 (.29,.41)1,2 |

|

| |||||

| Motor subtype | 229 | ||||

| PIGD | 137 (61.4) | 78 (79.6) | 39 (54.9) | 20 (37.0) | |

| Indeterminate | 20 (9.0) | 9 (9.2) | 7 (9.9) | 4 (7.4) | |

| Tremor dominant | 72 (31.4) | 11 (11.2) | 27 (37.0) | 34 (58.6) | |

MDS-UPDRS-3: Part 3 of the Movement Disorders Society-sponsored version of the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale; PASE: Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly; FOG: freezing of gait; PIGD: postural instability and gait disability.

Significantly different than the high fall risk trajectory (p<.05)

Significantly different than the medium fall risk trajectory (p<.05)

High scores indicate better performance

Figure 1.

Fall risk trajectories (A) and stable and fluctuating fall risk trajectories (B) in people with PD over a 2-year period according to fall risk scores (low risk: 0, medium risk: 2–6, high risk: 8–11) as determined by a simple fall risk prediction tool. Thin lines indicate the standard errors surrounding each trajectory.

The high fall risk trajectory was the most common (n=98, 42.6%) with 72.4% of these individuals identified by the prediction tool as being at high fall risk at baseline. The medium fall risk trajectory included 73 participants (31.7%), with 68% identified by the tool as being at medium fall risk at baseline. The low fall risk trajectory had 59 participants (25.7%), 91.5% of whom were identified by the tool as at low risk at baseline and generally remaining low risk at 2-years. The three trajectories were differentiated by their mean fall risk with no significant change over time (non-significant slope parameters).

The three components of the clinical fall prediction tool (fall history, gait speed, and FOF and PIGD score at baseline significantly differentiated the three fall risk trajectories over time (p<.001) (Tables 1 and 2). The fall risk trajectories did not vary by gender (p=.34) or age (p=.06). In general, it was easier to identify individuals in the high fall risk trajectory than those in the medium and low risk trajectories at baseline. Individuals in the high risk trajectory had significantly longer disease duration, increased disease severity based on PD motor scores and higher levodopa equivalent doses, greater amounts of dyskinesia and reduced physical activity levels than the medium risk trajectories (p<.001). By two years, PD motor scores significantly differentiated the three fall risk trajectories (p<.001). In contrast, physical activity levels and dyskinesia severity differentiated only high and low risk trajectories (p<.001 and p=.046, respectively) but not high and medium risk trajectories (p=.09 and p=.23, respectively).

Table 2.

Characteristics at the 2-year follow up, stratified by latent class analysis presented as mean (95% CI) or n (%).

| Variable | N | Analyzed cohort | Trajectory 1: High Fall Risk | Trajectory 2: Medium Fall Risk | Trajectory 3: Low Fall Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDS-UPDRS-3 (0 to 132) | 168 | 34.8 (32.5, 37.1) | 40.9 (37.0, 44.7) | 34.0 (30.0, 38.0)1 | 27.4 (24.0, 30.9)1,2 |

|

| |||||

| Levodopa equivalent dose (mg/day) | 171 | 689.5(617.9, 761.1) | 798.0 (684.0, 912.0) | 639.4 (520.0, 758.7) | 593.2 (449.5, 737.0) |

|

| |||||

| PASE score (0 to >400)† | 170 | 129.7 (117.5, 141.9) | 102.1 (87.5, 116.6) | 132.9 (111.7, 154.2) | 163.9 (136.6, 191.2)1 |

|

| |||||

| Fall risk category | 165 | 1 | 1,2 | ||

| High | 58 (35.2) | 47 (75.8) | 10 (17.9) | 1 (2.1) | |

| Med | 60 (36.4) | 15 (24.2) | 38 (67.9) | 7 (14.9) | |

| Low | 47 (28.5) | 0 (0) | 8 (14.3) | 39 (83.0) | |

|

| |||||

| Fall history | 170 | 1 | 1,2 | ||

| None | 95 (55.9) | 13 (19.7) | 37 (66.1) | 45 (93.8) | |

| One | 34 (20.0) | 15 (22.7) | 16 (28.6) | 3 (6.3) | |

| Multiple | 41 (24.1) | 38 (57.6) | 3 (5.4) | 0 (0) | |

|

| |||||

| Self-paced gait speed (m/s)† | 166 | 1.12 (1.09, 1.16) | 1.01 (.95, 1.07) | 1.11 (1.05, 1.17)1,2 | 1.30 (1.25, 1.34)1,2 |

|

| |||||

| FOG severity score (0 to 16) | 170 | 3.3 (2.7, 3.9) | 5.9 (5.0, 6.8) | 2.8 (1.8, 3.8)1,2 | .3 (−.1, .6)1,2 |

|

| |||||

| Dyskinesia severity (0 to 8) | 170 | .8 (.6, 1.1) | 1.2 (.8, 1.6) | .7 (.3, 1.1) | .5 (.2, .8)1 |

|

| |||||

| PIGD score (0 to >1.15) | 167 | .85 (.74, .96) | 1.31 (1.12, 1.50) | .74 (.60, .88)1 | .36 (.28, .43)1,2 |

|

| |||||

| Motor subtype | 166 | ||||

| PIGD | 107 (64.5) | 55 (87.3) | 35 (62.5) | 17 (36.2) | |

| Indeterminate | 21 (12.7) | 4 (6.4) | 8 (14.3) | 9 (19.2) | |

| Tremor dominant | 38 (22.9) | 4 (6.4) | 13 (23.2) | 21 (44.7) | |

MDS-UPDRS-3: Part 3 of the Movement Disorders Society-sponsored version of the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale; PASE: Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly; FOG: freezing of gait; PIGD: postural instability and gait disability.

Significantly different than the high fall risk trajectory (p<.05)

Significantly different than the medium fall risk trajectory (p<.05)

High scores indicate better performance

Fifty-two participants (22.6%) demonstrated a fluctuation in fall risk over the two years and were identified as having posterior probabilities <0.8 of belonging to any single trajectory (Table 3). These individuals appeared to fluctuate primarily between the medium and high risk trajectories (Table 2, Figure 1b). These participants had lower PIGD scores and were predominantly of tremor dominant or indeterminate motor subtypes at baseline compared to participants with stable fall risk trajectories. Shorter PD duration and gait speed reduction of 0.06 m/s over the first six months were also suggestive of fluctuating fall risk over time (p=.05–.07).

Table 3.

Characteristics of participants with stable (posterior probabilities ≥0.8, n=178) and fluctuating (posterior probabilities <0.8, n=52) fall risk trajectories. Scores are reported as mean (95% CI) or n (%).

| Variable | Baseline | Change over the first 6 months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stable risk trajectory (Probability ≥80) | Fluctuating risk trajectory (Probability <80) | p-value | Stable risk trajectory (Probability ≥80) | Fluctuating risk trajectory (Probability <80) | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 66.9 (65.5, 68.3) | 67.9 (65.6, 70.2) | .49 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Disease duration (years since diagnosis) | 6.2 (5.5, 6.9) | 4.8 (3.7, 5.9) | .05 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Levodopa equivalent dose (mg/day) | 589.8 (513.3, 666.4) | 454.1 (364.2, 544.1) | .08 | |||

|

| ||||||

| PIGD score baseline (0 to >1.15) | .83 (.72, .94) | .65 (.53, .77) | .03 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Motor subtype† | .03 | .99 | ||||

| PIGD / shift | 113 (64%) | 24 (46%) | 92 (57%) | 26 (58%) | ||

| Indeterminate / no change | 12 (7%) | 8 (15%) | 17 (11%) | 5 (11%) | ||

| Tremor dominant / shift | 52 (29%) | 20 (38%) | 52 (32%) | 14 (31%) | ||

|

| ||||||

| FOG severity score (0 to 16) | 3.2 (2.7, 3.8) | 2.8 (1.8, 3.9) | .52 | .4 (0, 0.7) | .1 (−.8, .9) | .47 |

|

| ||||||

| Self-paced gait speed (m/sec) | 1.18 (1.14, 1.22) | 1.22 (1.17, 1.28) | .21 | −.01 (−03, .02) | −06 (−.12, −.01) | .07 |

|

| ||||||

| PASE score (0 to >400) | 146.0 (133.7, 158.4) | 134.6 (114.2, 154.9) | .38 | −6.2 (−16.7, 4.4) | 4.9 (−12.7, 22.4) | .33 |

|

| ||||||

| Fall risk trajectory | .46 | |||||

| High | 73 (74.5) | 25 (25.5) | ||||

| Fall risk score (0 to 11) | 9.0 (8.4, 9.6) | 5.6 (4.4, 6.9) | <.001 | |||

| Medium | 56 (76.7) | 17 (23.3) | ||||

| Fall risk score (0 to 11) | 3.2 (2.6, 3.8) | 3.8 (2.2, 5.5) | .40 | |||

| Low | 49 (83.1) | 10 (16.9) | ||||

| Fall risk score (0 to 11) | 0.4 (−.2, .9) | 1.1 (−.2, 2.4) | .24 | |||

PIGD: postural instability and gait disability; FOG: freezing of gait; PASE: Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly.

LeA side of dash (/) indicates baseline PD subtype, right side of dash indicates shift in subtype, of lack thereof, over 6 months.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to document the natural, longitudinal fall risk trajectories of people with PD. Regardless of their baseline characteristics, most participants had clearly identifiable and stable fall risk trajectories over a 2-year period. The distinct trajectories, each defined by the presence of either low, medium, or high fall risk at multiple time points, provided important support for the idea that fall risk assessment in people with PD using a simple clinical tool appears to identify a relatively stable trait, rather than a potentially transient phenomenon vulnerable to influence by fatigue, distraction, general health status, or minor changes in disease progression.

We were somewhat surprised by the stability of the trajectories and had expected to see a greater incidence of increasing fall risk over two years in individuals with low or medium risk at baseline. Indeed, longitudinal studies have demonstrated that fall incidence in people with PD increased over time,5,25,26 although the time for increased fall incidence is of long duration ranging from 8–11.5 years.5,26 Given the short follow-up of our study, it may be that there was insufficient time available for changes in fall history, which is the strongest contributor to fall risk,6 FOG history, and preferred gait speed to have occurred.

Our results identified a relatively small group (<25%) of participants with fluctuating fall risk trajectories. These participants were mostly identified to be at moderate or high fall risk at baseline. Within this group there were individuals whose fall risk constantly fluctuated over time, some whose risk appeared to increase over time, and a few whose risk surprisingly decreased over time. Changes in fall history and in gait speed between each six-month time point appeared to be the main contributors to fluctuating fall risk. It is not altogether surprising that infrequent fallers who perhaps fall once or twice a year and whose fall history changes every six months would demonstrate fluctuating fall risk given that the prediction tool is weighted heavily by fall history.4

Gait deterioration has been identified to be strongly associated with falls27,28 and disability29 in people with PD, even during early stages of the disease.27,28 PIGD subtype is also associated with faster gait deterioration30 and increased fall frequency.26,31 It appeared that most individuals with PIGD in our study were already in the high fall risk trajectory. The small group of individuals with fluctuating fall risk trajectories generally had lower PIGD scores and were of tremor or indeterminate subtypes, indicating there was a potential for these individuals to transition towards greater PIGD impairment with further disease progression.32–34

Clinical and Research Implications

The combined prevalence (74.3%) of medium and high fall risk trajectories in our sample, especially among participants with the PIGD subtype, confirmed that gait and balance impairment appears to consistently contribute to falls and fall risk over time in people with PD. The result further reinforces the idea that frequent monitoring of gait and balance deterioration is a crucial aspect of PD management and rehabilitation.

The stability of most (77.3%) trajectories raises important questions for future clinical practice and research. Do stable trajectories simply represent an optimal baseline from which to measure the sustained impact of intervention, or could they suggest that sustained fall risk reduction may be difficult to achieve? Exercise and physical interventions targeting fall risk factors such as FOG, impaired balance and impaired mobility have been shown to reduce fall risk in the short-term in some at-risk individuals with PD,35 however the effects of such interventions on preventing falls are mixed.7–11 The duration and extent to which any reduction in falls and fall risk are sustained following intervention also remain unclear. It is likely that interventions to improve gait function in people with PD, particularly in early stages of disease, may also improve fall risk and reduce falls, although the persistence of such interventions need to be tested in future randomized trials.

Our results highlight that individuals who present with low PIGD scores at baseline appear more likely to have a fluctuating fall risk trajectory compared to those with gait and balance impairment, suggesting that a different intervention approach may be required for these individuals. These individuals are likely to have shorter disease duration but demonstrate deterioration in gait speed over the short term in the absence of marked balance impairment. Current management approaches have targeted balance interventions and falls prevention for people with moderate to severe disease when such impairments manifest,12,36 yet emerging evidence demonstrates that falls are more likely to be prevented in people with less rather than more severe disease.7 Early targeting of fall prevention intervention for individuals with low baseline PIGD scores, and regular follow up,36 may therefore be efficacious in reducing their likelihood of fall risk progression.

Study Limitations

This study had some limitations. First, the relatively small sample size and short follow-up period for tracking fall risk trajectories may have skewed the results. Future longitudinal studies, particularly those involving inception cohorts at time of PD diagnosis, will require longer follow up intervals to better identify changes in fall risk trajectory over time. Second, although our study represented a broad distribution of individuals with PD from across the USA and is likely to have accounted for much of the variability seen in this population, a longer follow-up period may better elucidate the presence or absence of a fluctuating risk category. Importantly, GMM assumes heterogeneity exists in the population and that all classes are represented. Third, the small number of participants with fluctuating fall risk trajectories in our cohort limited our ability to identify factors associated with progression of risk that may be remediable with intervention. Although in the minority, identifying these individuals is critical to targeting interventions appropriately. Fourth, emerging evidence suggests that impaired cognition, particularly in attention, orientation and impulsivity,37–39 contributes to increased fall risk in people with PD. However, we were unable to determine the possible influence of cognitive deterioration on fall risk trajectory, as we did not examine cognition in our participants. Finally, we tracked falls via participant recall over six months, which may have affected the accuracy of reporting. Nevertheless, participant recall is the current standard of care for gathering these data in clinical practice.36

CONCLUSIONS

A large proportion of individuals with PD who are identified to be at high risk of falls will fall within the next six months.4,16 Consequently, understanding the rate at which fall risk progresses in lower risk individuals and factors associated with such progression will better inform the targeting of individualized fall prevention strategies. This study demonstrated that fall risk, whether low, medium or high, remained relatively stable over a two-year period in most people with mild to moderate PD. Individuals with a high fall risk trajectory on average had longer and more severe disease and worse PIGD than individuals with low or moderate risk trajectories. Transition to PIGD subtype and deterioration in gait speed over six months were suggestive of fluctuating fall risk over time, highlighting the need for intervention to target gait impairments for management of falls and fall risk in people with PD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The information contained in this manuscript has not been presented elsewhere. Funding for this work was provided by the Davis Phinney Foundation, the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation, NIH R01 NS077959 and NIH UL1 TR000448, the Massachusetts and Utah Chapters of the American Parkinson Disease Association (APDA), the Greater St Louis Chapter of the APDA and the APDA Center for Advanced PD Research at Washington University.

The authors wish to thank the people with Parkinson’s disease who participated in this study.

List of abbreviations

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- BIC

Bayesian Information Criterion

- BLRT

Bootstrapped Likelihood Ratio Test

- FOG

freezing of gait

- GMM

growth mixture modelling

- LMR-LRT

Lo-Mendel-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test

- MDS-UPDRS

Movement Disorders Society sponsored version of the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- PIGD

postural instability and gait disability

Footnotes

All authors report no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Canning CG, Paul SS, Nieuwboer A. Prevention of falls in Parkinson’s disease: a review of fall risk factors and the role of physical interventions. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2014;4(3):203–221. doi: 10.2217/nmt.14.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lord SR, Ward JA, Williams P, Anstey KJ. An epidemiological study of falls in older community-dwelling women: the Randwick falls and fractures study. Aust J Public Health. 1993;17(3):240–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1993.tb00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker RW, Chaplin A, Hancock RL, Rutherford R, Gray WK. Hip fractures in people with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: incidence and outcomes. Mov Disord. 2013;28(3):334–340. doi: 10.1002/mds.25297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paul SS, Canning CG, Sherrington C, Lord SR, Close JCT, Fung VSC. Three simple clinical tests to accurately predict falls in people with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2013;28(5):655–662. doi: 10.1002/mds.25404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hely MA, Morris JGL, Reid WGJ, Trafficante R. Sydney multicenter study of Parkinson’s disease: Non-L-dopa-responsive problems dominate at 15 years. Mov Disord. 2005;20(2):190–199. doi: 10.1002/mds.20324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pickering RM, Grimbergen YAM, Rigney U, et al. A meta-analysis of six prospective studies of falling in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22(13):1892–1900. doi: 10.1002/mds.21598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canning CG, Sherrington C, Lord SR, et al. Exercise for falls prevention in Parkinson disease: A randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2015;84(3):304–312. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao Q, Leung A, Yang Y, et al. Effects of Tai Chi on balance and fall prevention in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2014 doi: 10.1177/0269215514521044. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Goodwin VA, Richards SH, Henley W, Ewings P, Taylor AH, Campbell JL. An exercise intervention to prevent falls in people with Parkinson’s disease: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(11):1232–1238. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-300919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li F, Harmer P, Fitzgerald K, et al. Tai chi and postural stability in patients with Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(6):511–519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris ME, Menz HB, McGinley JL, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Reduce Falls in People With Parkinson’s Disease. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1545968314565511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keus SH, Munneke M, Graziano M, et al. European Physiotherapy Guideline for Parkinson’s disease. The Netherlands: KNGF/ParkinsonNet; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stebbins GT, Goetz CG, Burn DJ, Jankovic J, Khoo TK, Tilley BC. How to identify tremor dominant and postural instability/gait difficulty groups with the movement disorder society unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale: Comparison with the unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. Mov Disord. 2013;28(5):668–670. doi: 10.1002/mds.25383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dibble LE, Cavanaugh JT, Earhart GM, Ellis TD, Ford MP, Foreman KB. Charting the progression of disability in parkinson disease: study protocol for a prospective longitudinal cohort study. BMC Neurol. 2010;10:110. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-10-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duncan RP, Cavanaugh JT, Earhart GM, et al. External validation of a simple clinical tool used to predict falls in people with Parkinson disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibson MJ, Andres RO, Isaacs B, Radebaugh T, Worm-Petersen J. The prevention of falls in later life. Dan Med Bull. 1987;34(Suppl 4):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giladi N, Shabtai H, Simon ES, Biran S, Tal J, Korczyn AD. Construction of freezing of gait questionnaire for patients with Parkinsonism. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2000;6(3):165–170. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8020(99)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomlinson CL, Stowe R, Patel S, Rick C, Gray R, Clarke CE. Systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25(15):2649–2653. doi: 10.1002/mds.23429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goetz CG, Tilley BC, Shaftman SR, et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov Disord. 2008;23(15):2129–2170. doi: 10.1002/mds.22340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): Development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(2):153–162. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCutcheon A. Latent Class Analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang MBT, Todner TE. Growth mixture modeling identifying and predicting unobserved subpopulations with longitudinal data. Organizational Research Methods. 2007;10(4):635–656. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. How to use a Monte Carlo study to decide on sample size and determine power. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9(4):599–620. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hely MA, Reid WGJ, Adena MA, Halliday GM, Morris JGL. The Sydney multicenter study of Parkinson’s disease: the inevitability of dementia at 20 years. Mov Disord. 2008;23(6):837–844. doi: 10.1002/mds.21956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiorth YH, Larsen JP, Lode K, Pedersen KF. Natural history of falls in a population-based cohort of patients with Parkinson’s disease: an 8-year prospective study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20(10):1059–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiss A, Herman T, Giladi N, Hausdorff JM. Objective assessment of fall risk in Parkinson’s disease using a body-fixed sensor worn for 3 days. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lord S, Burn D, Rochester L. Gait outcomes characterize people with Parkinson’s disease who transition to falling within the first year. Mov Disord. 2015;30(Suppl 1):S41. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shulman LM. Understanding disability in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25(Suppl 1):S131–S135. doi: 10.1002/mds.22789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galna B, Lord S, Burn DJ, Rochester L. Progression of gait dysfunction in incident Parkinson’s disease: Impact of medication and phenotype. Movement Disorders. 2015;30(3):359–367. doi: 10.1002/mds.26110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parashos SA, Wielinski CL, Giladi N, Gurevich T The National Parkinson Foundation Quality Improvement Initiative Investigators. Falls in Parkinson disease: analysis of a large cross-sectional cohort. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease. 2013;3:515–522. doi: 10.3233/JPD-130249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDermott MP, Jankovic J, Carter J, et al. Factors predictive of the need for levodopa therapy in early, untreated Parkinson’s disease. Arch Neurol. 1995;52(6):565–570. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540300037010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jankovic J, Kapadia AS. Functional decline in Parkinson’s disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58(10):1611–1615. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.10.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Coelln R, Barr E, Gruber-Baldini AL, et al. Can we predict motor subtype fidelity in patients with tremor-dominant Parkinson’s disease? Mov Disord. 2015;30(Suppl 1):S52. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allen NE, Canning CG, Sherrington C, et al. The effects of an exercise program on fall risk factors in people with Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Mov Disord. 2010;25(9):1217–1225. doi: 10.1002/mds.23082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Marck MA, Klok MP, Okun MS, Giladi N, Munneke M, Bloem BR. Consensus-based clinical practice recommendations for the examination and management of falls in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20(4):360–369. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allcock LM, Rowan EN, Steen IN, Wesnes K, Kenny RA, Burn DJ. Impaired attention predicts falling in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009;15(2):110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paul SS, Sherrington C, Canning CG, Fung VSC, Close JCT, Lord SR. The relative contribution of physical and cognitive fall risk factors in people with Parkinson’s disease: a large prospective cohort study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2014;28(3):282–290. doi: 10.1177/1545968313508470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smulders K, Esselink RA, Cools R, Bloem BR. Trait impulsivity is associated with the risk of falls in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e91190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.