Abstract

Objective

To compare the frequency of hospitalization rates between aspirating patients treated with gastrostomy versus those fed oral thickened liquids.

Study design

A retrospective review was performed of patients with an abnormal videofluoroscopic swallow study between February 2006 and August 2013. 114 patients at Boston Children's Hospital were included. Frequency, length, and type of hospitalizations within one year of abnormal swallow study or gastrostomy tube placement were analyzed using a negative binomial regression model.

Results

Gastrostomy tube fed patients had a median of 2 (IQR: 1, 3) admissions per year as compared with orally fed patients who had a 1 (IQR: 0, 1) admissions per year, p<0.0001. Patients fed by gastrostomy were hospitalized for more days (median 24 (IQR: 6, 53) days) versus orally fed patients (median: 2 (IQR: 1, 4) days, (P<0.001)). Despite the potential risk of feeding patients orally, no differences in total pulmonary admissions (IRR: 1.65 (95%CI [0.70, 3.84])) between the two groups were found, except gastrostomy tube patients had 2.58 times (95%CI [1.02, 6.49]) more urgent pulmonary admissions.

Conclusion

Patients who underwent gastrostomy tube placement for the treatment of aspiration had two times as many admissions as compared with aspirating patients fed orally. We recommend a trial of oral feeding in all children cleared to take nectar or honey thickened liquids prior to gastrostomy tube placement.

Keywords: aspiration, enteral tube, gastroenterology, thickening, oropharyngeal dysphagia

Aspiration during swallowing is a common diagnosis in infants and children with and without developmental delay. 1-7 Management approaches have included gastrostomy tube feeding, gastrostomy tube feeding with concurrent anti-reflux surgery (fundoplication), transpyloric feeding, and oral feeding with thickening of liquids. Gastrostomy tubes (g-tubes) are frequently used in order to allow for additional enteral access in patients with aspiration, including those thought to be at risk of having respiratory complications.8-11 Prior data have suggested that for children with neurologic disability, g-tube placement may improve respiratory outcomes, including decreased antibiotic use and respiratory related hospitalizations.12 Conversely, additional studies have shown that once placed, g-tubes are often fraught with complications, ranging from the minor (tube leakage, skin irritation, or formation of granulation tissue formation) to the more severe (worsening gastroesophageal reflux disease, g-tube cellulitis, or g-tube dislodgement).10, 13-15 To date, there have been no studies comparing clinical outcomes in aspirating children treated with oral thickened liquids to those treated with g-tube placement.12

Since the development of aerodigestive centers in which patients are seen by gastroenterologists and pulmonologists together along with other subspecialties (eg, feeding therapy, otolaryngology), there has been a practice shift at many institutions away from g-tube placement and more towards continuing to feed aspirating children orally with close combined gastroenterology, feeding team and pulmonary follow up. This shift has occurred in an effort to prevent feeding aversions and the complications surrounding g-tubes yet there are no data comparing outcomes of these patients undergoing continued oral feeding versus g-tube placement. Before 2010, it was common practice at Boston Children's Hospital to place g-tubes in patients who had aspiration confirmed by videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS). Prior data from our institution suggested that almost one-third of all patients undergoing primary percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube placement had a preoperative diagnosis of aspiration.9, 16 After 2010, many aspirating children continued to be fed orally with thickened liquids rather than by g-tube.

The primary aim of this study was to compare the frequency of hospitalizations between aspirating patients who were treated with g-tube placement versus those who were maintained on exclusive oral thickened feedings.

Methods

Institutional approval was granted to complete a retrospective chart review of patients with an abnormal VFSS at Boston Children's Hospital (BCH) between February 2006 and August 2013. Queries of hospital administrative data using Epic© (Version 2008) was performed to identify patients with a documented history of aspiration undergoing primary PEG tube placement; additional reviews of an ambulatory BCH Aerodigestive Clinic administrative list were used to identify patients with documented aspiration treated with oral thickened feeds.

All included patients had evidence of documented aspiration or penetration of thin liquids and/or nectar thick liquids via a VFSS. Any patient who had an unknown level of aspiration or aspirated all textures (thin, nectar, honey-thick, or pureed foods) were excluded. Enrolled patients were then divided into two groups: (1) patients who underwent g-tube placement without any preoperative documentation of an oral thickening feeding trial (g-tube group), or (2) patients who were continued on exclusive oral feeding with thickening agents (oral group). Any orally fed patients who subsequently required g-tube feedings were excluded from the primary analysis but were reanalyzed as a part of the orally fed cohort as a secondary analysis. We excluded any g-tube fed patients who went on to require post-pyloric feedings or fundoplication because in both of these cases, not only was oropharyngeal dysphagia treated but so was gastroesophageal reflux so clarifying the treatement effect of oropharyngeal dysphagia alone would not have been possible. All orally fed patients were treated with standardized thickening recipes using either infant cereal or xanthum gum.

Our primary outcome was defined as the total number of hospitalizations within one year of g-tube placement (for the g-tube fed group) or within one year of the first abnormal VFSS (for the oral fed group). Secondary outcomes included total number of inpatient days, frequency of subsequent pulmonary, gastroenterology or other types of admissions, as well as whether or not the hospitalization was elective or urgent within one year of their index event (either the placement of a g-tube or first abnormal VFSS). Urgent admissions were defined as any unplanned admission or admissions admitted through the Emergency Department. We also examined the number of patients who underwent a repeat VFSS within one year of their initial study (for oral group), or within one year of g-tube placement (for the g-tube group), as well as the frequency of normal repeat VFSS results. We also reviewed the patient characteristics of a subset of excluded orally fed patients, who went on to require g-tube feedings.

Patient records were reviewed for sex, age, and weight at the time of their first abnormal VFSS. Patient comorbidities were categorized as being neurologic, cardiac, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, oropharyngeal, renal, metabolic/genetic, immunologic, or having a history of premature birth (<37 weeks gestation). Comorbidities were not considered to be mutually exclusive. Extent and type of aspiration on VFSS were also recorded for all patients.

Patient characteristics for the g-tube group were compared with the oral group using both parametric and nonparametric methods as appropriate. Pearson's chi-square test was used for cross-tabulations unless any expected cell-count was <5, in which case Fisher's exact test was used. Student's t-test was used for continuous variables when normally distributed and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test otherwise.

A generalized linear model was used to adjust for subject characteristics, including neurologic, cardiac, and pulmonary comorbidities, as well as sex, age, and weight-for-age z-score. The primary and secondary outcomes, including number of hospitalization admissions as well as inpatient days among those hospitalized, were highly right-skewed, and the data were over-dispersed. Therefore, a negative binomial regression provided a better fit than a Poisson regression model, based on visual inspection of the regression curve overlaid on a plot of the mean predicted probability against the observed counts and the Akaike information criterion.17, 18 Outcomes were modeled using SAS® v9.3 (Cary, NC). Results were expressed on a multiplicative scale as the ratio of mean outcome in the g-tube group to mean outcome in the oral group (incidence rate ratio) with a 95% confidence interval (CI).19 An additional propensity score regression analysis was performed to include a propensity score to adjust for differences in the two populations. All statistical tests were two-sided with P<0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 114 patients were included in the analysis, 49 patients who were exclusively fed oral thickened feeds (oral group) and 65 patients who received a gastrostomy tube (g-tube group). Differences in subject characteristics at the time of study entry are shown in Table I. Patients did not differ statistically by sex, ethnicity, race or prematurity status at the time of their first abnormal VFSS, but subjects in the g-tube group were lower in weight (P=0.0003) and age (P=0.003) than those in the oral group. There was no difference in the prevalence of gastrointestinal comorbidities but g-tube patients were more likely to have cardiac, neurologic, metabolic and renal comorbidities, and orally fed subjects were more likely to have pulmonary and otolaryngology comorbidities.

Table 1.

Comparison of patient characteristics taken at the time of first abnormal swallow study for patients treated with oral thickening versus g-tube tube feedings (n=114).

| Orally Fed (n=49) | G-tube Fed (n=65) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | |||

| Female sex | 17 (35%) | 32 (49%) | 0.12 |

| Hispanic (unknown for n=29) | 5 (13%) | 7 (16%) | 0.69 |

| White | 37 (76%) | 41 (63%) | 0.16 |

| Prematurity | 21 (43%) | 24 (37%) | 0.52 |

| Age, median (IQR), months | 14.2 (8.2, 19.8) | 4.8 (2.0, 15.6) | 0.003 |

| Weight, median (IQR), kilograms | 10.4 (8.4, 12.2) | 6.4 (4.2, 9.3) | 0.0003 |

| Weight-for-age z-score | −0.11±1.81 | −1.31±2.63 | 0.005 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Gastrointestinal | 48 (98%) | 60 (92%) | 0.23 |

| Cardiac | 6 (12%) | 25 (38%) | 0.002 |

| Neurologic | 20 (41%) | 54 (83%) | <0.0001 |

| Pulmonary | 42 (86%) | 40 (62%) | 0.005 |

| Otolaryngology | 43 (88%) | 15 (23%) | <0.0001 |

| Metabolic | 8 (16%) | 26 (40%) | 0.006 |

| Renal | 0 (0%) | 11 (17%) | 0.002 |

| Immunologic | 3 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 0.31 |

P-values calculated from Chi-square, Fisher exact, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, or Student's t-test where appropriate

Aspiration of thin liquids alone was more prevalent among orally fed versus g-tube fed patients (36 (73%) versus 25 (38%), respectively; P<0.001) on the initial VFSS. Eighty (71%) patients, 32 fed orally and 49 fed with g-tube, underwent a repeat VFSS within a year. Of those patients who underwent repeat swallow studies, 6/32 (19%) orally fed patients versus 21/49 (43%) g-tube patients, had a subsequent normal VFSS (P=0.02).

Unadjusted results for total hospitalizations and inpatient days within one year of the first abnormal VFSS for the oral fed versus g-tube fed groups are shown in Table II. Median (IQR) total number of admissions was lower among the orally fed group than with the g-tube group (1 (0, 1) versus 2 (1, 3); P<0.0001), as was the total number of inpatient days (2 (1, 4) versus 24 (6, 53); P<0.0001). Patients in the orally fed group also had a lower prevalence of gastroenterology and ICU (Intensive Care Unit) admissions than g-tube fed patients (P<0.001) and similar rates of pulmonary admissions (P= 0.69).

Table 2.

Comparison of hospitalizations within one year of first abnormal swallow study (orally fed group) or within one year of g-tube placement (g-tube fed group; n=114).

| Orally Fed (n=49) | G-tube Fed (n=65) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of admissions, median (IQR) | 1 (0,1) | 2 (1, 3) | <0.0001 |

| Total number of Inpatient Days, median (IQR) | 2, (1, 4) | 24 (6, 52.5) | <0.0001 |

| Type of hospitalization, n (%) | |||

| Gastroenterology (GI) admission | 10 (20%) | 41 (63%) | <0.0001 |

| Pulmonary admission | 16 (33%) | 19 (29%) | 0.69 |

| Intensive Care Unit admission | 1 (2%) | 18 (28%) | 0.0003 |

| Other admission** | 13 (27%) | 28/65 (43%) | 0.07 |

P-value from Chi-square or Wilcoxon rank-sum test

Other included admissions: general surgery or other specialty surgical services (urology, orthopedics, otolaryngology), general pediatric services or other subspecialty medical services (nephrology, genetics/metabolism, coordinated care service, cardiology, or neurology)

Among the 94 patients ever admitted, there was no statistical difference between the two groups in the prevalence of urgent admissions overall (P=0.48; data not shown); however, among the 35 patients admitted for pulmonary care, 69% of orally fed group were admitted urgently as compared with 100% of g-tube group (P=0.01), even though these 35 patients were balanced with respect to pulmonary comorbidities (94% versus 95%, respectively; P=1.0).

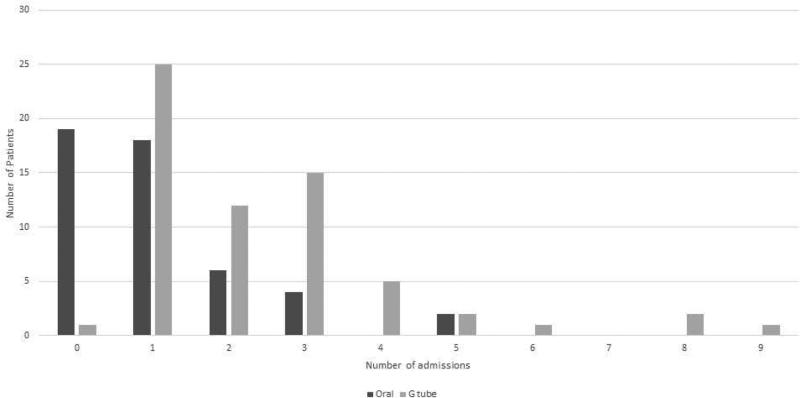

The distribution of total admissions for the orally fed and g tube fed patients is shown in Figure 1. For the urgent GI admissions, in the G tube group, 56% of admissions were for g tube related problems, 23% were for poor growth, 12% were for vomiting, 8% were for gastrointestinal infections. In the oral fed group, 83% had gastrointestinal infections and 17% had feeding difficulties.

Figure 1.

Distribution of admissions in orally fed patients and in patients with g tubes.

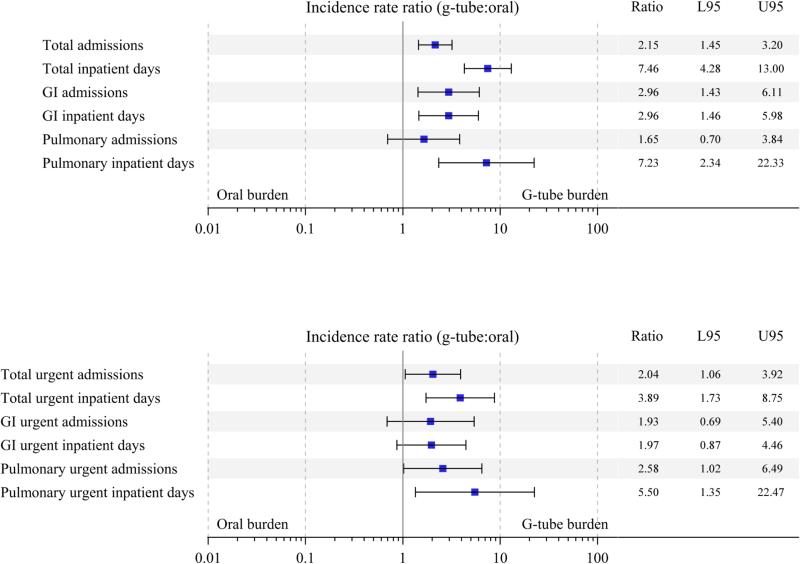

The results of negative binomial regression, used to investigate the independent effect of g-tube versus oral feeding on total and urgent admission rates, after adjusting for neurologic, cardiac, and pulmonary comorbidities, as well as sex, age, and weight, are shown in Figure 2. Patients treated with a g-tube had on average 2.15 (95% CI [1.45, 3.20]) times more total admissions, and among those admitted, 7.46 (95% CI [4.28, 13.0]) times more inpatient days than orally fed patients. On average, the g-tube group also had 2.96 (95% CI [1.43, 6.11]) times more gastroenterology admissions than the orally fed group; on review, these were likely due to more g-tube related admissions in the g-tube treated group. There were no differences in total pulmonary admissions (IRR: 1.65 (95%CI [0.70, 3.84])) or respiratory events between the two groups, but g-tube patients had 2.58 times (95%CI [1.02, 6.49]) more urgent pulmonary admissions than the orally fed patients. Of note, the proportion of patients with admissions for reasons other than gastroenterology or pulmonary were <10% in the either the g-tube group or oral group, and therefore was not modeled.

Figure 2.

Forest plots showing results of negative binomial regression, adjusted for neurologic, cardiac, and pulmonary comorbidities, as well as sex, age, and weight-for-age z-score. A, Total admissions and inpatient days among those admitted, as well as type of admissions. B, Total urgent admissions and inpatient days among those with urgent admissions, as well as types of urgent admissions. Results are expressed on a multiplicative scale, as the ratio of the incidence rate in the g-tube group to the incidence rate in the oral group. Analysis of inpatient days were restricted to admitted patients only.

Additionally, to try to reduce bias, we created a regression model adjusting for propensity score and gastrostomy tube status. Using this model, there were no differences in the directionality of the primary outcomes of total hospitalizations (IRR: 2.42 (1.46, 4.00)) and total hospitalization days (IRR: 11.37 (5.76,22.46)) compared with the regression model.

Of the initial patients screened for inclusion in the oral feeding group, an additional 11 patients failed thickening and went on to g-tube placement. To determine predictors of oral feeding failure, we compared the comorbidities of patients who were successful in oral trials compared with those who went on to g-tube placement. Patients who failed thickening trials had a higher rate of neurologic comorbidities (94% versus 42% respectively, p<0.001) and cardiac comorbidities (44% versus 12%, p=0.007). We also then included these “oral failure” patients in the total analysis in the oral group to reduce the chance that excluding these patients would create bias. When we redid the primary negative binomial regression model with these 11 patients included, there was no difference in any of the outcomes regarding significance but the IRR effect was attenuated. For the primary outcomes of total hospitalizations and total hospitalization days, the IRR comparing tube fed with orally fed patients (with the 11 “oral failures” included) were 1.75 (1.28,2.41) and 4.52 (2.92,6.99) respectively. Even when the “oral failure” patients were included, there were still significantly more hospitalizations and hospitalization days in the g tube patients.

To address whether the severity of aspiration affected hospitalization, we grouped patients into those that just aspirated thin liquids (n=61) and those that aspirated thin and nectar thick liquids (n=53). There was no difference in the total admissions in the thin (1.0 (1.0, 2.0) and thin and nectar (2.0 (1.0,3.0), p=0.7) or in the total hospitalization days between those that aspirate thin liquids (4.0 (2.0,40.0)) and those that aspirate thin and nectar (18.5 (3.5,36.6), p=0.08). After adjusting for g tube status, there were no differences in the comorbidities of those that aspirate thin versus thin and nectar except prematurity (p=0.002).

We also divided patients into those that had aspiration on their swallow study (n=103) and compared their rates of hospitalization with those that just had penetration (n=11) and found no difference in hospitalization rates or days between the two groups (p>0.5) but the sample size in the penetration group was small.

Discussion

Placement of a gastrostomy tube has historically been one of the primary methods for treatment for children with aspiration.8, 9, 11 There has been an increasing trend to continue to feed children by mouth in an effort to avoid the morbidity of g-tubes, which often includes not only potential mechanical complications from the tube itself (e.g. skin infections, tube dislodgement) but potential worsening of gastroesophageal reflux or development of prolonged oral aversions preventing patients from weaning off their g-tube feeds.8, 9, 20-23

The primary aim of this study was to determine if a modified oral feeding regimen with thickeners in aspirating children resulted in an increased risk of hospitalizations when compared with patients that were g-tube fed. We found that orally fed children were not admitted with any greater frequency than children who were g-tube dependent. In fact, children that were g-tube fed had on average twice the number of hospitalizations compared with those who were orally fed. In addition, there were no differences in the frequency of total pulmonary admissions between orally fed and g-tube patients suggesting that when you thicken oral feeds, you eliminate the risk of pneumonia which has been reported in children who aspirate thin liquids 6.

One explanation for why the presence of a g-tube may worsen outcomes in aspirating children is that g-tubes in certain children may increase the presence of gastroesophageal reflux which may result in an increased risk of adverse pulmonary outcomes. Several studies have addressed this issue. In one study, patients with feeding difficulties underwent either a g-tube placement or a combined g-tube placement with prophylactic fundoplication to prevent reflux-related complications.2 The authors found that the addition of an anti-reflux procedure to g-tube placement did not change the risk of respiratory complications, suggesting that aspiration of refluxed gastric contents did not contribute significantly to hospitalization risk. A similar study reviewing infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia, who received either a g-tube or a g-tube with Nissen fundoplication, found that pulmonary outcomes did not improve in either group over infants who were orally fed, again suggesting gastroesophageal reflux was not a significant issue in pulmonary morbidity. In fact, infants who underwent fundoplication had a significantly higher rate of rehospitalization.24 In both of these studies, the swallow function of the patients was not assessed. To address the impact of reflux and swallowing function, we studied hospitalization rates in 116 children who had gastroesophageal reflux testing by multichannel intraluminal impedance with pH testing and VFSS. We found that, even after adjusting for aspiration status, reflux burden did not predict the number of hospitalizations or the days hospitalized, suggesting that even in aspirating patients, reflux is not a significant contributor to hospitalizations.25

Another potential possibility for the differences in hospitalization rates is higher g-tube related admissions. Gastrointestinal causes for admission dominated and the most common reasons for the admission in the g-tube group were lengthy admissions at the time of tube placement, cellulitis, feeding intolerance, vomiting, and poor weight gain.

One limitation to our study is that children who were g-tube fed had more comorbidities that may have affected the decision to undergo g-tube placement, thereby biasing the results. Ideally we would also have compared admissions prior to and after g tube/oral thickening initiation but because of the young age of the patients included in the study, there was a very short “pre-intervention” time period to assess admissions. However, to try to address any possible bias, we have performed both a binomial regression model and propensity score analyses and both models gave identical results. Our results are in contrast to a single prior pediatric study which found a significant reduction in the frequency of antibiotic use and respiratory admissions in patients with cerebral palsy treated with g-tubes, including patients known to aspirate based on abnormal videofluoroscopy.12 In addition, there was no orally fed control group in this study, which may have also helped to better decipher if the g-tube itself also impacted admission rates. However, our findings that orally fed children have equivalent or fewer hospitalizations than g-tube fed patients are also similar to adult studies of patients with multiple comorbidities and who are at risk for impaired swallowing. Prior adult data have shown that both survival and aspiration pneumonia were either the same or better in patients that were orally fed compared with patients receiving enteral feeds. 26-29 Our results support a role for a trial of oral thickening before g-tube placement in any child whose swallow study shows that they are able to take either nectar or honey thickened liquids.

Of note, over half of the patients who underwent g-tube placement and repeat VFSS within one year of their surgery had improvement in their swallow function and these rates of aspiration resolution were actually higher in the g tube group than in the orally fed group. We hypothesize this finding represents the fact that, prior to the creation of aerodigestive centers, many patients with neonatal swallowing dysfunction underwent g-tube placement and this high rate of VFSS improvement represents a large proportion of very young patients with neonatal swallowing dysfunction in whom swallow function improves over time. Clearly the fact that many children experience improvement in swallow function over time should be factored into the decision on whether to place a g tube.

We have shown that oral thickened feeding is safe and well tolerated in the majority of aspirating patients. None of our patients receiving thickening were admitted for dehydration, and recent data supports the finding that thickening does not have any impact on dehydration risk as evidenced by water absorption studies.30, 31 We do recognize that some patients will not be able to maintain calories, hydration status, and lung health with thickened oral feeding, and we had 11 patients who failed oral thickening trials and ultimately needed g-tube placement. The risk factors for oral failure were concurrent cardiac and neurologic comorbidities. However, it is also important to note that some patients with neurologic symptoms and cardiac comorbidities were successful in oral feeding. Data from a study of patients with hypoplastic left heart undergoing interstage repair found that exclusive oral feeding resulted in improved weight gain versus infants who were treated with g-tube feedings.32 Therefore, more prospective studies are needed in order to better decipher which patients will go on to successful oral feeding trials versus those who will ultimately benefit from earlier g-tube placement.

Oral thickened feeding of children who aspirate thin or nectar liquids is a safe alternative to g-tube placement. Orally fed aspirating children have a decreased risk of hospitalization in comparison with g-tube fed children. We recommend a trial of oral feeding in children cleared to take thickened liquids, prior to g-tube placement, particularly in children with less comorbidity, significant underlying neurologic or other disability, or in those whose swallowing function is likely to improve over time.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Heather Litman, PhD, for her assistance in some preliminary statistical analyses used in preparing the manuscript.

Funded by the Boston Translational Research Program, North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition/ASTRA (Award for Diseases of the Upper Tract), and the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK097112-01A1).

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- IQR

Interquartile Range

- IRR

Incidence Rate Ratio

- CI

Confidence Interval

- G-tube

Gastrostomy Tube

- VFSS

Videofluoroscopic swallow study

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kakodkar K, Schroeder JW., Jr. Pediatric dysphagia. Pediatric clinics of North America. 2013;60:969–77. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnhart DC, Hall M, Mahant S, Goldin AB, Berry JG, Faix RG, et al. Effectiveness of fundoplication at the time of gastrostomy in infants with neurological impairment. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:911–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwarz SM, Corredor J, Fisher-Medina J, Cohen J, Rabinowitz S. Diagnosis and treatment of feeding disorders in children with developmental disabilities. Pediatrics. 2001;108:671–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheikh S, Allen E, Shell R, Hruschak J, Iram D, Castile R, et al. Chronic aspiration without gastroesophageal reflux as a cause of chronic respiratory symptoms in neurologically normal infants. Chest. 2001;120:1190–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.4.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heuschkel RB, Fletcher K, Hill A, Buonomo C, Bousvaros A, Nurko S. Isolated neonatal swallowing dysfunction: a case series and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:30–5. doi: 10.1023/a:1021722012250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weir K, McMahon S, Barry L, Ware R, Masters IB, Chang AB. Oropharyngeal aspiration and pneumonia in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007;42:1024–31. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weir KA, McMahon S, Taylor S, Chang AB. Oropharyngeal aspiration and silent aspiration in children. Chest. 2011;140:589–97. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox D, Campagna EJ, Friedlander J, Partrick DA, Rees DI, Kempe A. National trends and outcomes of pediatric gastrostomy tube placement. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2014;59:582–8. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McSweeney M, Kerr J, Jiang H, JLightdale JR. Risk Factors for Complications in a Large Cohort of Infants and Children with Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy (PEG) Tubes. J Pediatr. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.03.009. (available online 4/10/15) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lalanne A, Gottrand F, Salleron J, Puybasset-Jonquez AL, Guimber D, Turck D, et al. Long-term outcome of children receiving percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy feeding. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2014;59:172–6. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tutor JD, Gosa MM. Dysphagia and aspiration in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012;47:321–37. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sullivan PB, Morrice JS, Vernon-Roberts A, Grant H, Eltumi M, Thomas AG. Does gastrostomy tube feeding in children with cerebral palsy increase the risk of respiratory morbidity? Archives of disease in childhood. 2006;91:478–82. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.084442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ponsky TA, Gasior AC, Parry J, Sharp SW, Boulanger S, Parry R, et al. Need for subsequent fundoplication after gastrostomy based on patient characteristics. J Surg Res. 2013;179:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akay B, Capizzani TR, Lee AM, Drongowski RA, Geiger JD, Hirschl RB, et al. Gastrostomy tube placement in infants and children: is there a preferred technique? J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1147–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fortunato JE, Cuffari C. Outcomes of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in children. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2011;13:293–9. doi: 10.1007/s11894-011-0189-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McSweeney ME, Jiang H, Deutsch AJ, Atmadja M, Lightdale JR. Long-term outcomes of infants and children undergoing percutaneous endoscopy gastrostomy tube placement. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2013;57:663–7. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182a02624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawless JE. Negative Binomial and Mixed Poisson Regression. The Canadian Journal of Statistics. 1987;15:209–25. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akaike H. Likelihood of a Model and Information Criteria. Journal of Econometrics. 1981;16:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hilbe J. Proceedings of the Nineteenth Annual SAS Users Group International Conference. SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC: 1994. Log Negative Binomial Regression Using the GENMOD Procedure. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright CM, Smith KH, Morrison J. Withdrawing feeds from children on long term enteral feeding: factors associated with success and failure. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2011;96:433–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.179861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blackman JA, Nelson CL. Reinstituting oral feedings in children fed by gastrostomy tube. Clinical Pediatrics. 1985;24:434–8. doi: 10.1177/000992288502400803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomson M, Rao P, Rawat D, Wenzl TG. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and gastro-oesophageal reflux in neurologically impaired children. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:191–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i2.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Merwe WG, Brown RA, Ireland JD, Goddard E. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in children--a 5-year experience. S Afr Med J. 2003;93:781–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGrath-Morrow SA, Hayashi M, Aherrera AD, Collaco JM. Respiratory outcomes of children with BPD and gastrostomy tubes during the first 2 years of life. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49:537–43. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duncan DAA, Litman H, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux burden, even in patients that aspirate, does not increase hospitalization. 2015 Submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meier DE, Ahronheim JC, Morris J, Baskin-Lyons S, Morrison RS. High short-term mortality in hospitalized patients with advanced dementia: lack of benefit of tube feeding. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:594–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.4.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy LM, Lipman TO. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy does not prolong survival in patients with dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1351–3. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.11.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garrow D, Pride P, Moran W, Zapka J, Amella E, Delegge M. Feeding alternatives in patients with dementia: examining the evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1372–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finucane TE, Bynum JP. Use of tube feeding to prevent aspiration pneumonia. Lancet. 1996;348:1421–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharpe K, Ward L, Cichero J, Sopade P, Halley P. Thickened fluids and water absorption in rats and humans. Dysphagia. 2007;22:193–203. doi: 10.1007/s00455-006-9072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cichero JA. Thickening agents used for dysphagia management: effect on bioavailability of water, medication and feelings of satiety. Nutr J. 2013;12:54. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lambert LM, Pike NA, Medoff-Cooper B, Zak V, Pemberton VL, Young-Borkowski L, et al. Variation in feeding practices following the Norwood procedure. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2014;164:237–42. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]