Abstract

Objective

To determine neurodevelopmental outcome at two years’ corrected age in children randomized to treatment with dextrose gel or placebo for hypoglycemia soon after birth (The Sugar Babies Study).

Study design

This was a follow-up study of 184 children who had been hypoglycemic (< 2.6mM [45 mg/dL]) in the first 48 hours and randomized to either dextrose (90/118, 76%) or placebo gel (94/119, 79%). Assessments were performed at Kahikatea House, Hamilton, New Zealand, and included neurological function and general health (Pediatrician assessed), cognitive, language, behaviour and motor skills (Bayley-III), executive function (clinical assessment and BRIEF-P), and vision (clinical examination and global motion perception). Co-primary outcomes were neurosensory impairment (cognitive, language or motor score below −1 SD or cerebral palsy or blind or deaf) and processing difficulty (executive function or global motion perception worse than 1.5 SD from the mean). Statistical tests were two sided with 5% significance level.

Results

Mean (±SD) birth weight was 3093 ± 803 g and mean gestation was 37.7 ±1.6 weeks. Sixty-six children (36%) had neurosensory impairment (1 severe, 6 moderate, 59 mild) with similar rates in both groups (dextrose 38% vs. placebo 34%, RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.75–1.63). Processing difficulty was also similar between groups (dextrose 10% vs. placebo 18%, RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.23–1.15).

Conclusions

Dextrose gel is safe for treatment of neonatal hypoglycemia, but neurosensory impairment is common amongst these children.

Keywords: infant, newborn, neurodevelopment, executive function, vision, visual processing, infant of a diabetic mother, infant, preterm

Neonatal hypoglycemia is a common finding that is associated with brain injury1, neurodevelopmental delay2, 3, visual impairment4 and behavioral problems5. Between 5 and 15 % of otherwise healthy babies become hypoglycemic6 and the prevalence is increasing due to the increasing incidence of preterm birth7 and maternal diabetes8. Screening is recommended for babies with known risk factors, of whom half are likely to become hypoglycemic.9

Treatment of hypoglycemic babies varies considerably10. We previously reported a randomized trial of dextrose gel massaged into the buccal mucosa for treatment of neonatal hypoglycemia, (The Sugar Babies Study)11. Babies who received dextrose gel were less likely than those who received placebo to remain hypoglycemic, less likely to be admitted to NICU for hypoglycemia, and less likely to be formula fed at two weeks of age. Importantly, dextrose gel was safe, and it is inexpensive, simple to administer, and can be used in almost any setting.

Dextrose gel is now being used in some settings as first-line treatment for neonatal hypoglycemia12, 13. However, because the primary objective of treatment of neonatal hypoglycemia is to prevent brain injury, it is important to determine whether treatment with dextrose gel is associated with any beneficial or adverse effects on later development. Therefore, children who had participated in the Sugar Babies Study were invited to participate in this follow-up study. Our primary aim was to determine whether treatment of hypoglycemic babies with dextrose compared with placebo gel altered the rate of neurosensory impairment or processing difficulties at two years’ corrected age.

Methods

The Sugar Babies Study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial performed at a tertiary referral center (Waikato Women’s Hospital) in Hamilton, New Zealand (Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry: ACTRN 12608000623392) between December 1, 2008, and November 26, 2010, and has been reported previously11. In brief, eligible babies were ≥ 35 weeks gestation, < 48 hours old and at risk for neonatal hypoglycemia (infant of diabetic mothers, late preterm (35 or 36 weeks’ gestation), small (< 10th percentile or < 2500 g), large (> 90th percentile or > 4500 g), or other). Babies who became hypoglycemic (blood glucose concentration < 2.6 mM/L [45 mg/dL]) were randomized to receive either 40% dextrose gel or an identical appearing placebo gel 0.5ml/kg massaged into the buccal mucosa and were encouraged to feed. The primary outcome was treatment failure, defined as a blood glucose concentration < 2.6 mM after two treatment attempts. A total of 242 babies were randomized, of whom 237 met the eligibility criteria (five were randomized in error); 118 were randomized to dextrose and 119 to placebo gel.

All parents or caregivers of babies enrolled in the Sugar Babies Study were invited to participate in this follow-up study and provided written informed consent. Children were assessed at 24 months’ corrected age at Kahikatea Research House, Hamilton, New Zealand, in suitable local clinics or in the child’s own home. Families and all assessors were unaware of the neonatal treatment group allocation. The Sugar Babies study (NTY/08/03/025) and this follow-up study (NTY/10/03/021) were approved by the Northern Y Ethics Committee.

Development was assessed using the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition (Bayley-III)14. Executive function tests comprised four graded tasks, each scored out of six, to assess inhibitory control (Snack Delay, Shape Stroop), capacity for reverse categorization (Ducks and Buckets)15 and attentional flexibility (Multi-search Multi-location Task)16. Scores were summed to give an Executive Function Score of up to 24 points. In addition parents were asked to complete the Behaviour Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF-P) questionnaire17.

Visual assessment included measures of visual acuity (Cardiff Acuity Cards), stereopsis (Frisby stereotest and Lang stereotest), ocular health, alignment and motility, and non-cycloplegic refractive error (Suresight Autorefractor and retinoscopy). Dorsal visual pathway function was measured from optokinetic reflex responses to random dot kinematograms of varying coherence, as previously reported18. A motion coherence threshold corresponding to 63% correct was determined from a Weibull fit to the proportion of correct responses at different coherence levels

Children also underwent neurological examination, and standard growth measurements19. All children had newborn hearing screening at birth; an audiologist assessed any who failed neonatal screening. Details of family environment, socio-economic status and medical history were obtained by parental questionnaire.

The prespecified coprimary outcomes were neurosensory impairment (any impairment) and processing difficulty. Secondary outcomes were developmental delay, cerebral palsy, executive function composite score, BRIEF-P score, motion coherence threshold, vision problem, refractive error, deafness, growth, and history of seizures.

Neurosensory impairment was defined as mild (mild cerebral palsy or Bayley-III motor composite score 1 to 2 SD below the mean or mild developmental delay), moderate (moderate cerebral palsy or a Bayley-III motor composite score 2 to 3 SD below the mean or moderate developmental delay or deaf), or severe (severe cerebral palsy (the child is not ambulant at 2 years and likely to remain so) or Bayley-III motor composite score more than 3 SD below the mean or severe developmental delay or blind)20.

Developmental delay was defined as mild (Bayley-III cognitive or language composite scores 1 to 2 SD below the mean), moderate (Bayley-III cognitive or language composite scores 2 to 3 SD below the mean), or severe (Bayley-III cognitive or language composite scores more than 3 SD below the mean). Children unable to complete the cognitive, language or motor scales because of severe delay were assigned scores of 49. The Gross Motor Function Classification System was used to categorize cerebral palsy, according to Palisano21.

Children were considered to have a vision problem if they had any one of the following; internal ocular health problem, external ocular health problem, strabismus, abnormal ocular motility, no measurable stereopsis; binocular visual acuity > 0.5 LogMAR or unmeasurable. Blindness was defined as visual acuity ≥ 1.4 LogMAR in both eyes. Children were considered to have a refractive error if any of the following thresholds were reached22: retinoscopy measurements; hyperopia ≥ 2.75D, myopia ≥ 2.75D, astigmatism ≥ 1.25D, anisometropia ≥ 1.50D, autorefractor measurements; hyperopia ≥ 4.00D, myopia ≥ 1.00D, astigmatism ≥ 1.50D, anisometropia ≥3.00D. Because these parameters were highly correlated between right and left, eyes were selected at random for inclusion in the data analysis.

Processing difficulty was defined as either an Executive Function Score or a motion coherence threshold more than 1.5 SD from the mean (ie, in the bottom 7% of a cohort of 404 children born at risk of hypoglycemia, which included the children reported here).

Statistical analyses

Measurements of growth were converted to z-scores using WHO reference data. Socioeconomic status was categorized using the NZDep2006 index23.

Statistical tests were two sided and 5% significance level was maintained for the primary analysis by splitting the alpha value equally between the co-primary outcomes (ie, p <0.025 for either). For the primary outcomes, the proportion of children with neurosensory impairment and a processing difficulty were compared between those randomized to dextrose and those randomized to placebo using Chi-squared tests. For secondary and exploratory analyses groups were compared using generalized linear models (log-binomial for categorical variables, identify-normal for continuous variables), with adjustment for the reasons babies were identified as being at risk of hypoglycemia, socioeconomic status and sex, with no imputation for missing data.

Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary NC) and are presented as unadjusted median (range), mean (SD), relative risk (RR) or median difference and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

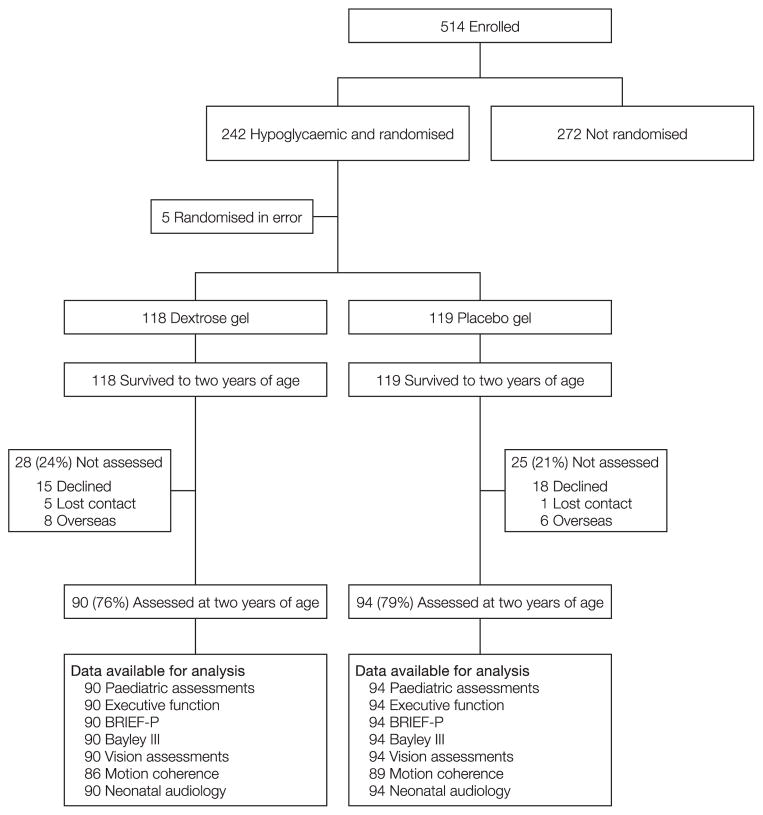

Of the 237 eligible babies assessed between July 21, 2010, and January 30, 2013, 184 (78%) were assessed at two years (Figure; available at www.jpeds.com). The characteristics of mothers of children who were and were not followed up were similar, except for higher parity in mothers of those who were followed up (Table I). The characteristics of children who were and were not assessed at two years were also similar, as were those of assessed children who were randomized to dextrose gel and placebo (Table I).

Figure 1.

Trial profile

Table 1.

Characteristics of mothers and babies who were and were not followed up, and those randomized to dextrose and placebo gel

| Not followed up | Followed up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Randomized to Dextrose Gel | Randomized to Placebo Gel | ||

| Mothers | 51 | 176$ | 88 | 91 |

| Age (y) | 29.4 ± 7.4 | 29.8 ± 6.0 | 29.6 ± 5.6 | 30.1 ± 6.3 |

| Parity | 0 (0 – 6) | 1 (0 – 10)* | 1 (0 – 7) | 1 (0 – 10) |

| BMI at booking (kg/m2) | 25.4 (18.8 – 43.6) | 26.7 (15.6 – 55.9) | 26.8 (15.6 – 55.9) | 26.6 (18.6 – 52.9) |

| Diabetes | 20 (39%) | 72 (41%) | 37 (42%) | 35 (38%) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| New Zealand European | 27 (53%) | 117 (66%) | 61 (69%) | 58 (64%) |

| Maori | 18 (35%) | 44 (25%) | 19 (22%) | 26 (29%) |

| Pacifica | 0 | 6 (3.4%) | 3 (3.4%) | 3 (3.3%) |

| Asian | 6 (12%) | 7 (4.0%) | 4 (4.6%) | 3 (3.3%) |

| Not Reported | 0 | 2 (1.1%) | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (1.1%) |

| Highest Education Level | ||||

| Secondary | N/A | 53 (32%) | 26 (32%) | 27 (32%) |

| Tertiary | N/A | 112 (67%) | 55 (67%) | 57 (68%) |

| Deprived families# | 27 (53%) | 65 (38%) | 29 (33%) | 36 (40%) |

| Babies | 53 | 184 | 90 (49) | 94 (51) |

| Male | 29 (55%) | 84 (46%) | 36 (40%) | 48 (51%) |

| Singleton | 46 (87%) | 153 (83%) | 75 (83%) | 78 (83%) |

| Ethnicity | N/A | |||

| New Zealand European | 88 (50%) | 46 (52%) | 42 (47%) | |

| Maori | 66 (37%) | 29 (33%) | 37 (42%) | |

| Other | 23 (13%) | 13 (15%) | 10 (11%) | |

| Vaginal birth | 34 (64%) | 113 (61%) | 57 (63%) | 56 (60%) |

| Gestation (wk) | 37.6 ± 1.6 | 37.7 ± 1.6 | 37.7 ± 1.6 | 37.7 ± 1.6 |

| Birthweight (g) | 2951 ± 799 | 3093 ± 802 | 3139 ± 804 | 3049 ± 803 |

| Birthweight z-score | −0.19 ± 1.57 | 0.14 ± 1.61 | 0.26 ± 1.64 | 0.02 ± 1.59 |

| Primary risk factor | ||||

| Maternal diabetes | 20 (38%) | 72 (39%) | 37 (41%) | 35 (37%) |

| Late preterm | 20 (38%) | 61 (33%) | 27 (30%) | 34 (36%) |

| Small | 6 (11%) | 29 (16%) | 16 (18%) | 13 (14%) |

| Large | 4 (8%) | 15 (8%) | 7 (8%) | 8 (9%) |

| Other | 3 (6%) | 7(4%) | 3 (3%) | 4 (4%) |

| Blood glucose concentrations (mM) | ||||

| Mean | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.4 |

| Minimum | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.4 |

| Admitted to NICU | ||||

| Total | 22 (42%) | 75 (41%) | 33 (37%) | 42 (45%) |

| For hypoglycemia | 8 (36%) | 39 (52%) | 13 (39%) | 26 (62%) |

Three mothers had babies who were randomized to both groups.

p < 0.05 for comparison between those who were and were not followed up.

# Deprived = NZDeprivation Index deciles 8 – 10. N/A = data not available Data are mean (SD), median (range), or number (%).

For the whole cohort of children followed up, the mean Bayley-III cognitive and language composite scores were 0.25 to 0.5 SD below the standardized mean. Mean T-scores on the BRIEF-P were higher (worse), than the standardized mean of 50 for all indices (Table II).

Table 2.

Outcomes at 2 years in babies randomized to dextrose or placebo gel

| Randomized to Dextrose Gel | Randomized to Placebo Gel | Relative risk or mean difference (95% CI) | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 90 | n = 94 | |||||

| n | n | |||||

| Age at assessment (months) | 90 | 24.2 ± 1.2 | 94 | 24.5 ± 1.9 | −0.31 (−0.77 – 0.15) | 0.18 |

| Primary outcomes | ||||||

| Neurosensory impairment | 90 | 34 (38%) | 94 | 32 (34%) | 1.11 (0.75 – 1.63) | 0.60 |

| None | 56 (62%) | 62 (66%) | ||||

| Mild | 28 (31%) | 31 (33%) | ||||

| Moderate | 5 (6%) | 1 (1%) | ||||

| Severe | 1 (1) | 0 (0%) | ||||

| Processing difficulty | 84 | 8 (10%) | 87 | 16 (18%) | 0.52 (0.23 – 1.15) | 0.10 |

| Secondary Outcomes | ||||||

| Developmental delay | 90 | 31 (34%) | 93 | 30 (32%) | 1.07 (0.71 – 1.61) | 0.75 |

| None | 59 (66%) | 63 (68%) | ||||

| Mild | 25 (28%) | 29 (31%) | ||||

| Moderate | 5 (6%) | 1 (1%) | ||||

| Severe | 1 (1%) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Cerebral Palsy | 2 (2%) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Bayley-III Composite scores | ||||||

| Cognitive | 90 | 93 ± 11 | 93 | 94 ± 9 | −1.30 (−4.21 – 1.61) | 0.38 |

| Language | 89 | 96 ± 14 | 93 | 96 ± 13 | −0.72 (−3.14 – 4.58) | 0.71 |

| Motor | 90 | 99 ± 10 | 93 | 99 ± 9 | −0.36 (−3.04 – 2.33) | 0.80 |

| Social emotional | 88 | 105 ± 15 | 90 | 104 ± 16 | −0.43 (−4.12 – 4.99) | 0.85 |

| General adaptive | 89 | 101 ± 13 | 91 | 99 ± 14 | 1.34 (−2.70 – 5.38) | 0.52 |

| Executive function | 87 | 92 | ||||

| Composite score | 10.9 ± 4.1 | 10.0 ± 4.0 | 0.93 (−0.24 – 2.11) | 0.12 | ||

| Children with z-score < −1.5 | 5 (6%) | 8 (9%) | 0.66 (0.22 – 1.94) | 0.45 | ||

| Brief-P Index scores | 89 | 93 | ||||

| Inhibitory Self Control | 55 ± 11 | 54 ± 10 | 1.09 (−1.88 – 4.06) | 0.47 | ||

| Flexibility | 52 ± 10 | 52 ± 10 | 0.24 (−2.67 – 3.15) | 0.87 | ||

| Emergent Metacognition | 60 ± 12 | 58 ± 12 | 2.17 (−1.26 – 5.60) | 0.21 | ||

| Global Executive Composite | 58 ± 11 | 56 ± 11 | 1.71 (−1.48 – 4.89) | 0.29 | ||

| Vision | 86 | 89 | ||||

| Motion coherence threshold | 40.2 ± 12.8 | 41.5 ± 15.7 | −1.31 (−5.55 – 2.93) | 0.55 | ||

| Children with z-score > 1.5 | 4 (5%) | 8 (9%) | 0.52 (0.16 – 1.66) | 0.27 | ||

| Vision problem | 90 | 26 (29%) | 93 | 23 (25%) | 1.17 (0.72 – 1.89) | 0.53 |

| Refractive error | 51 | 3 (6%) | 49 | 5 (10%) | 0.58 (0.15 – 2.28) | 0.43 |

| Anthropometry (z-scores) | ||||||

| Weight | 89 | 0.79 ± 1.10 | 91 | 0.52 ± 0.99 | 0.26 (−0.04 – 0.57) | 0.09 |

| Height | 90 | −0.01 ± 1.09 | 90 | −0.24 ± 1.17 | 0.24 (−0.09 – 0.57) | 0.16 |

| BMI | 89 | 1.12 ± 1.12 | 90 | 0.96 ± 0.84 | 0.16 (−0.13 – 0.45) | 0.27 |

| Head circumference | 90 | 0.86 ± 1.05 | 94 | 0.83 ± 1.21 | 0.03 (−0.30 – 0.35) | 0.88 |

| Arm circumference | 90 | 1.08 ± 1.00 | 91 | 0.92 ± 0.97 | 0.15 (−0.13 – 0.44) | 0.29 |

| Seizures | 90 | 4 (4%) | 91 | 5 (5%) | ||

Data are number (%), or mean ± SD

Sixty-six children (36%) were found to have neurosensory impairment, although most of this was mild (Table II). Rates of impairment were similar in both treatment groups (dextrose 34/90 [38%] vs. placebo 32/94 [34%], RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.63, p = 0.60). The rate of processing difficulty was also similar in both treatment groups (dextrose 8/84 [10%] vs. placebo 16/87 [18%] RR 0.52, 95%CI 0.23 to 1.15, p = 0.10) (Table II).

Sixty one children (33%) were found to be developmentally delayed (severe 1, moderate 6, mild 54), with similar rates in both treatment groups (dextrose 31/90 [34%] vs. placebo 30/93 [(32%], RR 1.07 95% CI 0.71 to 1.61, p =0.75). Two children had mild cerebral palsy. No children were blind or deaf. Forty-nine of 183 children tested (27%) had vision problems and 8/100 (8%) had a refractive error, with no difference between groups. Nine children experienced seizures, with six of these reported as febrile seizures (four in the dextrose and two in the placebo group), (Table II). There were no differences between groups in any growth measurements (Table II). Adjustment for hypoglycemia risk factors, socioeconomic status and sex did not change any of the findings.

Discussion

Dextrose gel is attractive as a primary treatment for neonatal hypoglycemia because it is simple, inexpensive, and with no adverse effects detected in the neonatal period.11 This follow-up study provides evidence that treatment with dextrose gel is not associated with adverse effects at two years’ corrected age. These findings are consistent across assessment of a broad range of functions including neurodevelopment, executive function, vision and growth.

The major reason for treating neonatal hypoglycemia is to prevent hypoglycemia-induced brain injury. Because dextrose gel was effective in reversing hypoglycemia11, we might have expected improved outcomes at two years. However, we found no evidence of improved outcomes in babies treated with dextrose gel. This may be because all babies enrolled in the study were treated when a blood glucose concentration of < 2.6mM (45 mg/dL) was detected. Hypoglycemic babies were treated with either dextrose or placebo gel and fed, and the blood glucose concentration was measured again 30 minutes later. Treatment could be repeated once, and if the baby remained hypoglycemic after the second dose of gel, the baby was admitted to NICU for further treatment. Thus babies randomized to the placebo gel group would have had additional treatment delayed by approximately one hour, and the proportion of time babies were hypoglycemic in the first 48 hours was not significantly prolonged (placebo 6.1%, 95% CI 0.0 to 37.9% vs. dextrose 3.0%, 95% CI 0.0 to 31.8%, p = 0.13).11 The duration and severity of hypoglycemia required to cause brain injury in any individual baby is not known.6 However, in the context of the relatively low risk group of babies that we studied, and routine monitoring and treatment of blood glucose concentrations of < 2.6mM, there was no apparent benefit of more prompt treatment of hypoglycemia using dextrose gel on developmental outcomes at two years of age.

An alternative explanation for the lack of apparent benefit of treatment with dextrose gel may have been inadequate power to detect differences in outcome between groups. Our study had 92% power to detect a 5-point difference between groups in any of the Bayley-III composite scores, and the mean scores were almost identical between groups. Thus, it is unlikely that we would have failed to detect a clinically significant difference in developmental delay between groups. On the other hand, in the group randomized to dextrose gel, the number of children with a processing difficulty was half that of the group randomized to placebo, and the confidence intervals around the relative risk were wider (RR 0.52; 95% CI 0.23 to 1.15, p = 0.10), suggesting that we may not have had sufficient power to exclude a type 2 error for this outcome.

We are not aware of other reports regarding neurodevelopmental outcome from a similar cohort at risk of hypoglycemia. However, the rate of mild neurosensory impairment in our cohort appears higher than expected from the Bayley-III test standardization. Increased risk of neurodevelopmental impairment has been reported in late-preterm24, small for gestational age25 and infants of diabetic mothers5 related to the abnormal intrauterine environment, or shortened gestation. Neonatal hypoglycemia is reported to be an important predictor of developmental delay in late preterm babies, and lower treatment thresholds may be associated with poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes2. Further, it was recently reported in a regional birth cohort that transient neonatal hypoglycemia was related to school performance at 10 years of age, with a graded relationship between severity of the hypoglycemia and the odds of achieving proficiency in literacy and numeracy26. Nevertheless, it is not possible to determine whether these observed associations are causal, or whether neonatal hypoglycemia is a marker of impaired metabolic adaptation in infants who are already at risk for adverse later outcomes. Randomized trials comparing treatments at different thresholds will be required to address this question27.

It is possible that the higher-than-expected rate of mild impairment in this cohort may be an underestimate, as the Bayley-III assessment has been reported to underestimate poor neurodevelopmental outcomes in at-risk British and Australian children28, 29. It is therefore important that our cohort is followed up at older ages. Our cohort will be re-assessed at 4.5 years corrected age, when neurosensory and processing difficulty outcomes can be more completely assessed.

A strength of our prospective study is the robust assessment of both visual global motion perception and executive function into a single measure that we called processing difficulty, because both assessments target cortical networks that may be susceptible to neonatal hypoglycemia. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain in animal and human studies 30, 31 suggest that the occipital lobe may be particularly vulnerable to the injury caused by neonatal hypoglycemia, and a link between hypoglycemia and visual impairment has previously been reported4, 30. In this context, visual global motion perception was of particular interest as it involves extrastriate visual areas within the dorsal visual cortical processing stream, which emanates from the occipital lobe32–34. The combination of vision screening using standard clinical tests and a psychophysical measure of processing within the extrastriate visual cortex (global motion perception) is novel in 2-year olds and was intended to detect differences in visual development between the dextrose gel and placebo groups.

Recommendations for the follow-up of high-risk babies now also include the assessment of subtle neurocognitive and executive function35. Executive function is a collective term for the skills required to learn and interact with the environment, including working memory, reasoning, task flexibility and problem solving. Findings from neuroimaging data show that these skills involve a network of areas within the brain36. Because there are no standardized tests for executive function in two-year-old children, we adapted tests that previously had been shown to be predictive of emerging executive function at 24 months37. Scores from these tests were converted to z-scores for comparing outcomes between groups.

Despite considerable effort, we succeeded in assessing only 78% of the children randomized. However, the similarity in baseline characteristics between those who were and were not assessed suggests that a systematic bias is unlikely. This report of outcomes after a randomized trial of dextrose gel for treatment of hypoglycemia provides important reassurance for those who are beginning to treat neonatal hypoglycemia with dextrose gel that later adverse outcomes due to dextrose gel are unlikely in term and late preterm babies treated to maintain a blood glucose concentration >2.6mmol/L in the first 48 hours. These findings cannot be extrapolated to other groups of neonates such as more preterm babies or those with congenital hypoglycemic disorders.

We previously have shown dextrose gel is effective in reversing neonatal hypoglycemia, and has no adverse effects in the newborn period. This study shows that treatment with dextrose gel is not associated with additional risks or benefits at two years of age. Clinicians and families can be reassured that the advantages of treatment with dextrose gel soon after birth are not counterbalanced by increased risk of poor neurodevelopmental outcome at two years’ corrected age.

Acknowledgments

The Sugar Babies Study was funded by the Waikato Medical Research Foundation, the Auckland Medical Research Foundation, the Maurice and Phyllis Paykel Trust, the Health Research Council of New Zealand, and the Rebecca Roberts Scholarship. The Follow-up Study was funded by the Health Research Council of New Zealand and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (R01HD0692201).

The authors would like to acknowledge the children and families who participated in the Sugar Babies follow up study.

Members of the CHYLD Study Team include:

University of Auckland (Auckland, New Zealand): Judith Ansell, MedPsych, PgDip, PhD; Coila Bevan, BA; Jessica Brosnanhan, BSc, PgDip; Ellen Campbell, BSc, BA, MSc; Tineke Crawford, BHSc, PgDip; Kelly Fredell, BNurs; Karen Frost, BHSc; Greg Gamble, BSc, MSc; Anna Gsell, PhD; Claire Hahnhaussen, BSc; Safayet Hossin, BSc, MSc; Yannan Jiang, PhD; Kelly Jones PgDippsychprac, PhD; Sapphire Martin, BNurs; Chris McKinlay, MBChB, DipProfEthics, PhD; Grace McKnight, Christina McQuoid, MedDip Psych; Janine Paynter, BHSc (Hon), PhD; Jenny Rogers, BSc, PgDip; Kate Sommers, Heather Stewart, RN, RM; Anna Timmings, MBChB, BMedSci (Hons); Jess Wilson, BSc, MSc; Rebecca Young, B Ed; Nicola Anstice, BOptom, PhD; Jo Arthur, BOptom; Susanne Bruder BOptom; Arijit Chakraborty, BOptom; Robert Jacobs, PhD; Gill Matheson, BOptom; Nabin Paudel, BOptom; Tzu-Ying (Sandy) Yu, BOptom, PhD.

University of Canterbury (Christchurch, New Zealand): Matthew Signal, BE (Hon), PhD; Aaron Le Compte, PhD.

Waikato Hospital, (Hamilton, New Zealand): Max Berry, MBBS, PhD; Arun Nair, MD (Paed) DCH; Ailsa Tuck, MBChB; Alexandra Wallace, MBChB, PhD; Phil Weston, MBChB.

Steering Group--University of Auckland (Auckland, New Zealand): Jane Alsweiler, MBChB, PhD, Jane Harding, MBChB, DPhil (Chair), Ben Thompson, BSc, PhD, Trecia Wouldes, BA, MA, PhD; University of Canterbury (Christchurch, New Zealand): J. Geoffrey Chase, BS, MS, PhD; Waikato District Health Board (Hamilton, New Zealand): Deborah Harris, Dip Nursing, MHSc (Hons), PhD.

International Advisory Group--Stanford University School of Medicine (Stanford, California): Heidi Feldman, MD, PhD, Darrell Wilson, BS, MD; University of Colorado School of Medicine (Denver, Colorado): William Hay, BA, MD; McGill University (Montreal, Canada): Robert Hess, BSc, MSc, PhD, DSc.

Footnotes

Trial registration Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry: ACTRN 12608000623392

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding bodies

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Burns CM, Rutherford MA, Boardman JP, Cowan FM. Patterns of cerebral injury and neurodevelopmental outcomes after symptomatic neonatal hypoglycemia. Pediatrics. 2008;122:65–74. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerstjens JM, Bocca-Tjeertes IF, de Winter AF, Reijneveld SA, Bos AF. Neonatal morbidities and developmental delay in moderately preterm-born children. Pediatrics. 2012;130:265–72. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lucas A, Morley R, Cole TJ. Adverse neurodevelopmental outcome of moderate neonatal hypoglycaemia. BMJ. 1988;297:1304–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6659.1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tam EW, Widjaja E, Blaser SI, MacGregor DL, Satodia P, Moore AM. Occipital lobe injury and cortical visual outcomes after neonatal hypoglycemia. Pediatrics. 2008;122:507–12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stenninger E, Flink R, Eriksson B, Sahlen C. Long term neurological dysfunction and neonatal hypoglycaemia after diabetic pregnancy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1988;79:F174–F9. doi: 10.1136/fn.79.3.f174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hay WW, Raju T, Higgins R, Kalhan S, Devaskar S. Knowledge gaps and research needs for understanding and treating neonatal hypoglycemia: workshop report from Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. J Pediatr. 2009;155:612–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, Chou D, Moller AB, Narwal R, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet. 2012;379:2162–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–53. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris DL, Weston PJ, Harding JE. Incidence of neonatal hypoglycemia in babies identified as at risk. J Pediatr. 2012;161:787–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris DL, Weston PJ, Battin MR, Harding JE. A survey of the management of neonatal hypoglycaemia within the Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network. J Paediatr Child Health. 2009;26:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2009.01599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris DL, Weston PJ, Signal M, Chase JG, Harding JE. Dextrose gel for neonatal hypoglycaemia (the Sugar Babies Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382:2077–83. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61645-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett C, Headtke E, Rowe-Telow M. Use of dextrose gel reverses neonatal hypoglycaemia and decreases admissions to the NICU. JGONN. 2015;44:S52. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ter M, Halibullah I, Sudholz H, Leung L, Jacobs S. Implementation of dextrose gel in neonatal hypoglycaemia managment. J Paediatr Child Health. 2015;51:68. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bayley N. Bayley scales of infant and toddler development. 3. Psychcorp; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlson SM, Mandell DJ, Williams L. Executive function and theory of mind: stability and prediction from ages 2 to 3. Dev Psychol. 2004;40:1105–22. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zelazo PD, Reznick JS, Spinazzola J. Representational flexibility and response control in a multistep multilocation search task. Dev Psychol. 1998;34:203–14. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gioia GA, Isquith PK, Guy SC, Kenworthy L. The behavior rating inventory of executive function. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu TY, Jacobs RJ, Anstice NS, Paudel N, Harding JE, Thompson B, et al. Global motion perception in 2 year old children: a method for psychophysical assessment and relationships with clinical measures of visual function. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:8408–19. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ministry of Health. New Zealand-World Heatlh Organization growth charts: fact sheet 3: measuring and plotting. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crowther CA, Doyle LW, Haslam RR, Hiller JE, Harding JE, Robinson JS. Outcomes at 2 years of age after repeat doses of antenatal corticosteroids. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1179–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, Russell D, Wood E, Galuppi B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39:214–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt P, Maguire M, Dobson V, Quinn G, Ciner E, Cyert L, et al. Comparison of preschool vision screening tests as administered by licensed eye care professionals in the Vision In Preschoolers Study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:637–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salmond C, Crampton P, Atkinson J. NZDep2006 Index of Deprivation. Wellington: University of Otago; 2007. pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petrini JR, Dias T, McCormick MC, Massolo ML, Green NS, Escobar GJ. Increased risk of adverse neurological development for late preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2009;154:169–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arcangeli T, Thilaganathan B, Hooper R, Khan KS, Bhide A. Neurodevelopmental delay in small babies at term: a systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;40:267–75. doi: 10.1002/uog.11112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaiser JR, Bai S, Gibson N, Holland G, Lin TM, Swearingen CJ, et al. Association between transient newborn hypoglycemia and fourth-grade achievement test proficiency: A population- based study. JAMA Pediatr. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKinlay CJ, Harding JE. Revisiting transitional hypoglycemia: Only time will tell. JAMA Pediatr. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson PJ, De Luca CR, Hutchinson E, Roberts G, Doyle LW Victorian Infant Collaborative G. Underestimation of developmental delay by the new Bayley-III Scale. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:352–6. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moore T, Johnson S, Haider S, Hennessy E, Marlow N. Relationship between test scores using the second and third editions of the Bayley Scales in extremely preterm children. J Pediatr. 2012;160:553–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alkalay AL, Flores-Sarnat L, Sarnat HB, Moser FG, Simmons CF. Brain imaging findings in neonatal hypoglycemia: case report and review of 23 cases. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2005;44:783–90. doi: 10.1177/000992280504400906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vannucci RC, Vannucci SJ. Hypoglycemic brain injury. Seminars in Neonatology. 2001;6:147–55. doi: 10.1053/siny.2001.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braddick OJ, O’Brien JM, Wattam-Bell J, Atkinson J, Hartley T, Turner R. Brain areas sensitive to coherent visual motion. Perception. 2001;30:61–72. doi: 10.1068/p3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKeefry DJ, Watson JD, Frackowiak RS, Fong K, Zeki S. The activity in human areas V1/V2, V3, and V5 during the perception of coherent and incoherent motion. Neuroimage. 1997;5:1–12. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newsome WT, Britten KH, Movshon JA. Neuronal correlates of a perceptual decision. Nature. 1989;341:52–4. doi: 10.1038/341052a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Follow-up Care of High-Risk Infants. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1377–97. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collette F, Van der Linden M. Brain imaging of the central executive component of working memory. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2002;26:105–25. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(01)00063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carlson SM. Developmentally sensitive measures of executive function in preschool children. Dev Neuropsychol. 2005;28:595–616. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2802_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]