This is the first phase II trial in which adding oral leucovorin (LV) to S-1 (SL) significantly prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) when compared with S-1 monotherapy (S) in patients with gemcitabine-refractory advanced pancreatic cancer (PC). The significantly better PFS and disease control rate with SL than with S suggest that the antitumor activity of S-1 is enhanced by LV in advanced PC.

Keywords: phase II study, S-1, leucovorin, gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer, pancreatic resection, albumin

Abstract

Background

We evaluated the efficacy and toxicity of adding oral leucovorin (LV) to S-1 when compared with S-1 monotherapy in patients with gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer (PC).

Patients and methods

Gemcitabine-refractory PC patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive S-1 at 40, 50, or 60 mg according to body surface area plus LV 25 mg, both given orally twice daily for 1 week, repeated every 2 weeks (SL group), or S-1 monotherapy at the same dose as the SL group for 4 weeks, repeated every 6 weeks (S-1 group). The primary end point was progression-free survival (PFS).

Results

Among 142 patients enrolled, 140 were eligible for efficacy assessment (SL: n = 69 and S-1: n = 71). PFS was significantly longer in the SL group than in the S-1 group [median PFS, 3.8 versus 2.7 months; hazard ratio (HR), 0.56; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.37–0.85; P = 0.003]). The disease control rate was significantly higher in the SL group than in the S-1 group (91% versus 72%; P = 0.004). Overall survival (OS) was similar in both groups (median OS, 6.3 versus 6.1 months; HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.54–1.22; P = 0.463). After adjusting for patient background factors in a multivariate analysis, OS tended to be better in the SL group (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.47–1.07; P = 0.099). Both treatments were well tolerated, although gastrointestinal toxicities were slightly more severe in the SL group.

Conclusion

The addition of LV to S-1 significantly improved PFS in patients with gemcitabine-refractory advanced PC, and a phase III trial has been initiated in a similar setting.

Clinical trials number

Japan Pharmaceutical Information Center: JapicCTI-111554.

introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC), known for its poor prognosis, is the eighth leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the world [1]. Although FOLFIRINOX has become a standard regimen for advanced PC, its use is limited to patients in good medical condition because of its severe toxicity [2]. Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel is another treatment option for patients in fair condition [3]. Some patients still receive gemcitabine monotherapy as first-line treatment.

Even with intensive chemotherapy regimens such as FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel, the median progression-free survival (PFS) is ∼6 months. Furthermore, a considerable number of patients cannot tolerate intensive chemotherapy after first-line chemotherapy. Although a combination of oxaliplatin, leucovorin (LV), and fluorouracil (OFF) prolonged survival when compared with fluorouracil plus LV (FF) after gemcitabine failure (CONKO-003 trial) [4], there are various unmet needs that should be addressed in a second-line setting for advanced PC.

In Japan, S-1 (Taiho Pharmaceutical, Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), an oral fluoropyrimidine that inhibits dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, has been demonstrated to be non-inferior to gemcitabine as first-line chemotherapy for advanced PC [5]. In gemcitabine-refractory patients, a previous phase II study reported that S-1 was moderately effective, with a response rate (RR) of 15%, a median PFS of 2.0 months, and a median overall survival (OS) of 4.5 months [6]. Furthermore, although oxaliplatin and irinotecan can be key drugs, neither S-1 plus oxaliplatin nor S-1 plus irinotecan provided a survival benefit over S-1 monotherapy in patients with gemcitabine-refractory PC [7, 8]. Because S-1 monotherapy is less toxic than these doublet regimens, it is widely used in gemcitabine-refractory patients as the practical standard care in Japan.

LV is known to enhance the efficacy of fluorouracil in metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) [9]. In preclinical studies, combined treatment with LV and S-1 was suggested to enhance therapeutic efficacy [10]. A randomized phase II study suggested that adding to LV to capecitabine might not increase efficacy because of increased intolerable toxicities [11]. Given the time-dependent antitumor effects and toxicities of fluoropyrimidine plus LV, various schedules of S-1 plus LV (SL) were studied in metastatic CRC, and a 2-week schedule (1 week on, 1 week off) was designated as the optimal schedule, maintaining high antitumor efficacy with manageable toxicity [12, 13]. These findings encouraged us to perform a randomized phase II clinical trial comparing SL with S-1 monotherapy in patients with gemcitabine-refractory advanced PC.

methods

study design

This multicenter, open-labeled, randomized phase II study, sponsored by Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan, was conducted at 27 centers in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. An independent data and safety monitoring committee reviewed efficacy and safety data. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of each participating center. All patients provided written informed consent before study entry.

patients

Eligible patients were 20–79 years of age and had a histologically or cytologically confirmed diagnosis of adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma of the pancreas that was refractory to first-line treatment with gemcitabine. Patients had measurable lesions according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST; version 1.1). Other eligibility criteria were as follows: (i) no prior radiotherapy for PC, (ii) an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) of 0 or 1, and (iii) adequate bone-marrow, hepatic, and renal functions on laboratory tests carried out within 7 days before enrollment. Patients could have no serious comorbidities (supplementary Appendix SA2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Disease progression during first-line gemcitabine-based chemotherapy or recurrence during or within 6 months after the completion of postoperative adjuvant gemcitabine chemotherapy was assessed on computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or other imaging techniques and was confirmed by an independent review committee (IRC).

randomization

After confirming eligibility, patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive S-1 plus LV (SL group) or S-1 monotherapy (S-1 group). Random assignment was carried out centrally at an independent data center by the minimization method, using the duration of prior gemcitabine treatment (≤6 versus >6 months) and ECOG PS (0 versus 1) as allocation factors.

treatment

The dose of S-1 was determined according to the body surface area as follows: <1.25 m2, 40 mg; 1.25 to <1.5 m2, 50 mg; and ≥1.5 m2, 60 mg, given twice daily after meals in both treatment groups. In the SL group, LV at a fixed dose of 25 mg was additionally given with each dose of S-1. Patients assigned to the SL group received S-1 plus LV orally for 1 week, followed by a 1-week rest, repeated every 2 weeks. Patients assigned to the S-1 group received the same dose of S-1 orally for 4 consecutive weeks, followed by a 2-week rest, repeated every 6 weeks. The details of dose modification of S-1 are defined in supplementary Appendix SA3, available at Annals of Oncology online. Treatment was continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxic effects, or the withdrawal of consent.

assessments

Patients' conditions were assessed every 2 weeks during the protocol treatment. All adverse events were evaluated according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.0). CT or MRI was carried out every 4 weeks during the first 16 weeks and every 6 weeks thereafter until disease progression. Response was assessed by the attending physicians and confirmed by the IRC according to RECIST version 1.1. If there was any discordance between an investigator and the IRC, the date of disease progression as evaluated by the IRC was used to calculate PFS. Data on patients in whom treatment was discontinued before disease progression was confirmed by the IRC were censored on the last day of tumor assessment (no events).

end points

The primary end point was PFS, defined as the time from randomization to disease progression or death from any cause. Secondary end points were OS, RR, disease control rate (DCR), duration of response, time to treatment failure (TTF), time to progression (TTP), dose intensity, and adverse events (supplementary Appendix SA4, available at Annals of Oncology online).

statistical analysis

The hazard ratio (HR) for PFS was expected to be 0.67, corresponding to a median PFS of 3.0 months in the SL group and 2.0 months in the S-1 group. These estimates were based on the results of a previous study [6]. To detect such an improvement in the HR with ≥80% power and a one-sided significance level of 0.10, a total of 110 events of progressive disease confirmed by the IRC in the full analysis set (FAS) were required. Given a 10% loss of events due to discordance in the PFS assessment between the IRC and the investigators and a 5% dropout rate from the FAS for various reasons, the sample size was set at 140 patients. Time-to-event variables, such as PFS, OS, TTF, and TTP, were analyzed with the Kaplan–Meier method, and the HR for these end points was calculated with a Cox proportional-hazards model. Primary comparisons of PFS between the treatment groups were made with the stratified log-rank test adjusted for allocation factors. The secondary end points of OS, TTF, and TTP were analyzed with the use of log-rank tests. RR and DCR were compared with the use of Fisher's exact test. Interaction tests between treatment effect and patient characteristics were done for PFS and OS.

The FAS was based on all eligible patients, and the safety analysis set was defined as the patients who received the study treatment at least once. Data analyses were carried out with the use of SAS, version 9.2. Subset analyses were pre-planned.

results

patients

Between August 2011 and August 2012, a total of 142 patients were enrolled. All randomized patients were confirmed to have gemcitabine-refractory PC by the IRC. A total of 140 patients were eligible and included in the FAS (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Two patients in the SL group were ineligible because they had no target lesions on IRC assessment. There were some imbalances in patient characteristics, such as the serum albumin level, sum of the diameters of target lesions, and prior pancreatic resection (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| S-1/LV (n = 69) | S-1 (n = 71) | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 41 (59.4) | 38 (53.5) | F: 0.500 |

| Female | 28 (40.6) | 33 (46.5) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean | 64.2 | 63.3 | t: 0.444 |

| Median | 65.0 | 64.0 | |

| <65 | 34 (49.3) | 38 (53.5) | F: 0.735 |

| ≥65 | 35 (50.7) | 33 (46.5) | |

| BSA (m2) | |||

| Median | 1.538 | 1.547 | t: 0.932 |

| Range | 1.165–1.861 | 1.225–1.953 | |

| <1.250 | 3 (4.3) | 2 (2.8) | W: 0.705 |

| 1.250 to <1.500 | 28 (40.6) | 28 (39.4) | |

| 1.500–< | 38 (55.1) | 41 (57.7) | |

| ECOG PS | |||

| 0 | 45 (65.2) | 48 (67.6) | F: 0.858 |

| 1 | 24 (34.8) | 23 (32.4) | |

| Albumin (g/dL) | |||

| <4.0 | 39 (56.5) | 30 (42.3) | F: 0.128 |

| ≥4.0 | 30 (43.5) | 41 (57.7) | |

| Sum of the diameter of target lesions (mm) | |||

| Mean | 48.0 | 42.1 | t: 0.181 |

| Median | 44.7 | 35.3 | |

| Pancreatic resection | |||

| No | 56 (81.2) | 47 (66.2) | F: 0.056 |

| Yes | 13 (18.8) | 24 (33.8) | |

| Treatment duration of first-line gemcitabine | |||

| ≤6 months | 52 (75.4) | 54 (76.1) | F: 1.000 |

| >6 months | 17 (24.6) | 17 (23.9) | |

| Previous gemcitabine treatment | |||

| Advanced | 58 (84.1) | 55 (77.5) | F: 0.394 |

| Recurrent (adjuvant chemotherapy) | 11 (15.9) | 16 (22.5) | |

ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status.

aP-values were calculated with Fisher's exact test (F), t-test (t) or Wilcoxon's rank-sum test (W).

efficacy

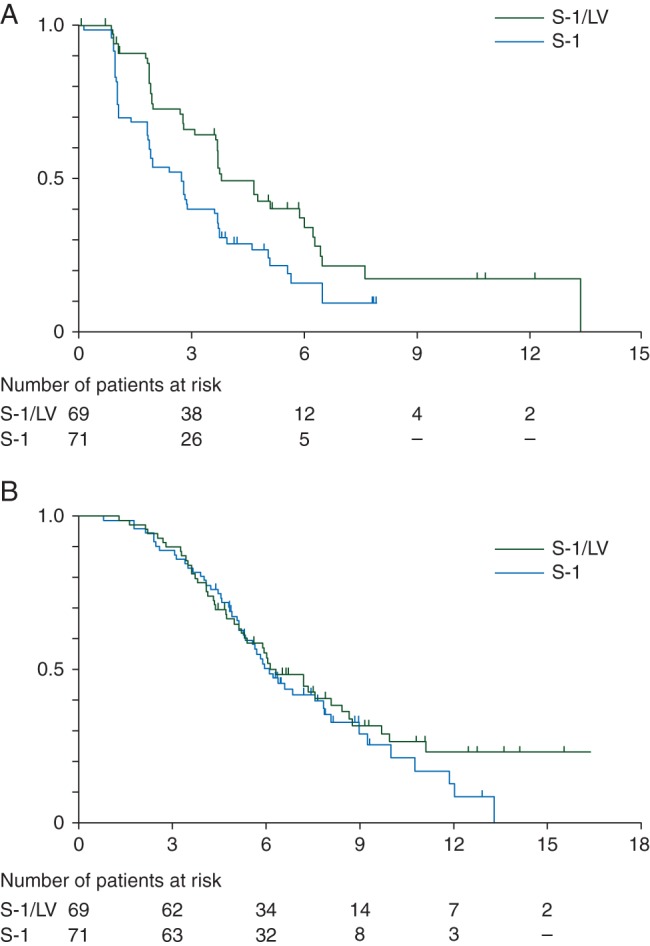

At the cut-off date for PFS analysis of 17 December 2012, when 117 events had been reported by the investigators, 97 events were confirmed, and data on 25 patients were censored by the IRC. The median PFS was 3.8 months [95% confidence interval (CI), 3.7–6.0 months] in the SL group and 2.7 months (95% CI, 1.9–3.7 months) in the S-1 group (Figure 1A). SL significantly decreased the risk of disease progression by 44% when compared with S-1 (HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.37–0.85; P = 0.003). The results for TTP were exactly the same as those for PFS because no death occurred before disease progression. In the pre-specified subgroup analyses of PFS, the effect of SL was better in most categories (supplementary Figure S2A, available at Annals of Oncology online). On multivariate analysis adjusting for patient characteristics such as gender, age, number of metastatic organs, pancreatic resection, and albumin levels in addition to stratification factors (ECOG PS, duration of gemcitabine treatment), the HR was 0.50 in favor of SL (95% CI, 0.33–0.77; P = 0.001).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves of (A) progression-free survival (assessed by independent review committee) and (B) overall survival.

The median OS was 6.3 months (95% CI, 5.3–8.4 months) in the SL group and 6.1 months (95% CI, 5.3–7.8 months) in the S-1 group (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.54–1.22; P = 0.463) (Figure 1B). In the pre-specified subgroup analyses of OS, the effect of SL was better in most categories (supplementary Figure S2B, available at Annals of Oncology online). However, some interactions between treatment effect and patient backgrounds, such as prior pancreatic resection and albumin level, were suggested. The HR on multivariate analysis adjusting for patient characteristics was 0.71 in favor of SL (95% CI, 0.47–1.07, P = 0.099) (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

The RR was 27.5% (95% CI, 17.5%–39.6%) in the SL group and 19.7% (95% CI, 11.2%–30.9%) in the S-1 group (P = 0.322) (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). The DCR was 91.3% (95% CI, 82.0%–96.7%) in the SL group and 71.8% (95% CI, 59.9%–81.9%) in the S-1 group (P = 0.004). The median duration of response was 96.5 days in the SL group and 73.0 days in the S-1 group.

At the cut-off date for PFS analysis, the protocol treatment was being continued in 19 patients (27.5%) in the SL group and 16 patients (22.5%) in the S-1 group. The median TTF was 3.7 months (95% CI, 2.6–3.8 months) in the SL group and 2.4 months (95% CI, 1.8–2.9 months) in the S-1 group. The main reason for treatment discontinuation was disease progression (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Post-protocol treatment was given to 27 patients (39.1%) in the SL group and 30 patients (42.3%) in the S-1 group (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). The main post-protocol treatments (≥10 patients) were S-1 monotherapy in the SL group and gemcitabine plus S-1 in the S-1 group.

safety

The treatment-related grade 3 or 4 adverse events with ≥5% incidences were anemia (9.9% in the SL group versus 11.3% in the S-1 group), lymphopenia (12.7% versus 11.3%), neutropenia (8.5% versus 5.6%), leukopenia (7.0% versus 4.2%), hyponatremia (5.6% versus 2.8%), diarrhea (5.6% versus 4.2%), fatigue (7.0% versus 0.0%), and decreased appetite (14.1% versus 4.2%) (Table 2). Serious adverse events related to the protocol treatment occurred in 11 patients (15.5%) in the SL group and 8 patients (11.3%) in the S-1 group. Two patients in the SL group died from treatment-related sepsis.

Table 2.

Treatment-related adverse events (safety analysis population)

| S-1/LV (n = 71) |

S-1 (n = 71) |

P-valuea (any grade) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade | Grade 3–4 | Any grade | Grade 3–4 | ||

| Hematological analysis | |||||

| Anemia | 20 (28.2%) | 7 (9.9%) | 22 (31.0%) | 8 (11.3%) | 0.854 |

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 15 (21.1%) | 9 (12.7%) | 13 (18.3%) | 8 (11.3%) | 0.833 |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 17 (23.9%) | 6 (8.5%) | 16 (22.5%) | 4 (5.6%) | 1.000 |

| Platelet count decreased | 16 (22.5%) | 2 (2.8%) | 17 (23.9%) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Weight decreased | 12 (16.9%) | 3 (4.2%) | 10 (14.1%) | 0 | 0.817 |

| White blood cell count decreased | 16 (22.5%) | 5 (7.0%) | 18 (25.4%) | 3 (4.2%) | 0.844 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 8 (11.3%) | 0 | 11 (15.5%) | 3 (4.2%) | 0.623 |

| Non-hematological analysis | |||||

| Lacrimation increased | 12 (16.9%) | 0 | 16 (22.5%) | 0 | 0.527 |

| Diarrhea | 37 (52.1%) | 4 (5.6%) | 36 (50.7%) | 3 (4.2%) | 1.000 |

| Nausea | 35 (49.3%) | 1 (1.4%) | 20 (28.2%) | 2 (2.8%) | 0.016 |

| Stomatitis | 43 (60.6%) | 2 (2.8%) | 21 (29.6%) | 0 | 0.0004 |

| Vomiting | 20 (28.2%) | 0 | 13 (18.3%) | 2 (2.8%) | 0.233 |

| Fatigue | 23 (32.4%) | 5 (7.0%) | 18 (25.4%) | 0 | 0.459 |

| Malaise | 18 (25.4%) | 0 | 15 (21.1%) | 0 | 0.691 |

| Pyrexia | 8 (11.3%) | 0 | 4 (5.6%) | 0 | 0.366 |

| Decreased appetite | 47 (66.2%) | 10 (14.1%) | 34 (47.9%) | 3 (4.2%) | 0.042 |

| Dysgeusia | 16 (22.5%) | 0 | 10 (14.1%) | 0 | 0.563 |

| Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome | 17 (23.9%) | 0 | 17 (23.9%) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Maculopapular rash | 14 (19.7%) | 0 | 4 (5.6%) | 0 | 0.021 |

| Skin hyperpigmentation | 46 (64.8%) | 0 | 31 (43.7%) | 0 | 0.018 |

aP-values were calculated with Fisher's exact test for the difference in the incidence of adverse events of any grade.

The median relative dose intensity (RDI) of S-1 was 91.0% (range, 28.6%–100%) in the SL group and 92.3% (range, 14.3%–103.7%) in the S-1 group. The main reasons for dose reduction of S-1 and treatment interruption were gastrointestinal toxicities in both groups.

discussion

The significantly better PFS and DCR in the SL group than in the S-1 group suggest that the antitumor activity of S-1 is enhanced by LV in advanced PC. Several clinical studies have shown that adding LV to S-1 enhances antitumor efficacy [12–14]. These results together with the present study provide robust evidence for the enhancement of S-1 activity by LV.

Several regimens of second-line chemotherapy, including OFF and FF plus MM-398, have obtained a median OS of ∼6 months [4, 15]. A recent comprehensive analysis of second-line chemotherapy for advanced PC reported that the median OS was 6.0 months in patients who received chemotherapy when compared with only 2.8 months in those who received best supportive care (P = 0.013) [16]. In the GEST study, more than 70% of the patients in the gemcitabine monotherapy group received S-1 monotherapy or S-1-based regimens as second-line chemotherapy [5], and the median OS after gemcitabine failure was ∼6.0 months. Development of S-1-based regimens seemed especially attractive in this setting, and we therefore directly estimated the benefits of LV added to S-1 when compared with S-1 monotherapy.

Because PC is not a chemotherapy-sensitive tumor, especially in patients receiving second-line treatment, disease control is considered clinically relevant at present. The main objective of this randomized phase II trial was to estimate the increment in effectiveness obtained by adding LV to S-1, and thereby facilitate planning of a subsequent phase III trial with the primary end point of OS. We designated PFS as the primary end point of our trial, and OS, RR, and DCR were secondary end points. As expected, PFS and DCR were significantly better in the SL group than in the S-1 group.

No difference in OS was observed between the two treatment groups, and several reasons may account for this. First, subsequent treatment might have biased the comparison of OS. The regimens used for subsequent treatment differed substantially between the groups, although the proportions of patients who received subsequent chemotherapy were similar. Secondly, there were non-negligible differences in patient backgrounds such as prior pancreatic resection and the serum albumin level between the treatment groups (Table 1) due to small sample size; and there were some interactions between the patients' background characteristics and the response to treatment in terms of both PFS and OS (supplementary Figure S2A and B, available at Annals of Oncology online). In particular, both prior pancreatic resection and the serum albumin level were prognostic factors for OS (supplementary Figure S3A and B, available at Annals of Oncology online). In fact, multivariate analysis of OS adjusting not only for stratification factors, but also for patient background characteristics resulted in a lower HR (0.71; 95% CI, 0.47–1.07; P = 0.099) than that of the primary analysis (0.82; 95% CI, 0.54–1.22; P = 0.463). It is speculated that the efficacy of SL, especially in terms of OS, might be underestimated because of some bias related to background characteristics and subsequent treatment. Pancreatic resection and the albumin level should thus be considered as eligibility criteria, stratification factors, or both in future phase III trials.

Treatments were well tolerated, and high RDI (>90%) was maintained in both treatment arms. However, gastrointestinal toxicities were slightly more severe in the SL group. PC is generally associated with malnutrition and sometimes cachexia, especially later in the clinical course of the disease. Cachexia induces sarcopenia, which increases adverse effects of chemotherapy [17]. Serum albumin levels have been reported to be an index of sarcopenia [18]. In fact, the incidences of some adverse effects (e.g. anemia, diarrhea, nausea, and malaise) in our study were higher in patients with low albumin levels than in those with normal albumin levels, especially in the SL group (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). Patient selection for second-line chemotherapy for advanced PC is considered very important, especially when a toxic regimen is used.

As for second-line treatment after gemcitabine-based chemotherapy, the use of FOLFIRINOX seems to be limited by its severe toxicity. Regimens with relatively mild chemotherapy and a low risk of severe toxicity (e.g. OFF) are most likely suitable for the second-line chemotherapy of PC. In this respect, SL is considered a promising option for second-line treatment after gemcitabine-based regimens in patients with advanced PC.

Our study had several limitations. First, since it was not placebo-controlled, a bias in PFS evaluation cannot be ruled out. To minimize this bias, disease progression in the treatment arms was confirmed by an IRC under blinded conditions. Secondly, the sample size was small, as discussed above. Thirdly, the primary end point was not OS but PFS. Initially, PFS was not expected to be largely affected by patient background characteristics, and post-progression survival was likely to be short in this setting. Therefore, we thought that PFS would be more suitable than OS to evaluate the benefit of adding LV. However, imbalances in the patients' backgrounds appeared to affect both PFS and OS. Furthermore, differences in subsequent chemotherapy influenced post-progression survival. Although the discrepancy between PFS and OS makes it rather difficult to interpret our results, multivariate analysis of OS suggests a survival benefit of SL.

In conclusion, LV was shown to have an additive effect with S-1 on PFS and DCR and was associated with tolerable toxicity as second-line chemotherapy for patients with gemcitabine-refractory advanced PC. A phase III study to evaluate the survival benefits of SL when compared with S-1 is ongoing in Japan and Korea (JapicCTI-132172).

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

We thank the patients, their families, and all the investigators who participated in the study (detailed in the supplementary Appendix SA1, available at Annals of Oncology online) for their contributions. We also thank Yoshihiko Maehara, Keisuke Aiba, Yoshiharu Motoo, Junji Tanaka, Atsushi Sato, Yuko Kobashi, and Yuh Sakata. The authors thank Takanori Tanase (Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) for their contributions to the study design and data analysis. We thank Peter Star of Medical Network K.K., (Tokyo, Japan) for his review of this report, funded by Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. We would like to thank Teruaki Matsuyama and Atsuki Shinozaki, Taiho Pharmaceuticals, for overall management of the trial and drafting the manuscript.

funding

This work was funded by Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. No grant number applies.

disclosure

MU received honoraria from Abbott, Eli Lilly, Yakult, and AstraZeneca and research funding from Eli Lilly, Kowa, Taiho, Yakult, Daiichi-Sankyo, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Zeria, Merck Serono, and AstraZeneca. TO received honoraria from Chugai, Pfizer, Novartis, Taiho, Merck Serono, Eli Lilly, Dainippon Sumitomo, Eisai, and Bayer, and has served as a consultant for Eli Lilly, Yakult, Amgen, Dainippon Sumitomo, Taiho, OncoTherapy Science, Nobelpharma, Ono, Boehringer, NanoCarrier, Chugai, Novartis, and Zeria, and received research funding from Chugai, Eli Lilly, Eisai, Novartis, Shizuoka Industry, Takeda Bio Development Center, Yakult, OncoTherapy Science, Otsuka, Taiho, Sceti Medical Labo, Boehringer, Kowa, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Merck Serono, Ono, Bayer, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Dainippon Sumitomo. YO received research funding from Taiho, Chugai, Eli Lilly, Amgen, and Ono. HI is a member of the speakers' bureau for Junken Medical, MSD, Aska, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Eisai, Otsuka, Olympus, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Century Medical, Daiichi-Sankyo, Dainippon Sumitomo, Taiho, Takeda, Chugai, Eli Lilly, Zeon, Piolax, Hitachi Medical, Fuji Film Medical, Boston Scientific, Yakult, Roche Diagnostic, and Medico's Hirata, and has received research funding from Junken Medical, Ajinomoto, Eisai, Olympus, Shionogi, Century Medical, Taiho, Chugai, Teijin Pharma, Eli Lilly, Zeon, Hitachi Medical, Pfizer, Fuji Film, Boston Scientific, Merck Serono, Yakult, Piolax, and Public Health Research Center. FA has received honoraria and research funding from Eli Lily, Yakult, and Taiho. He is also a member of the speakers' bureau for Taiho. MI has received research funding from Bayer, Novartis, Merck Serono, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Yakult, Taiho, Eli Lilly, Otsuka, OncoTherapy Science, Boehringer, Kowa, Ono, Eisai, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Glaxo Smith Kline, and Zeria. He is also a member of the speakers' bureau for Taiho, Bayer, Novartis, Bristol Myers, Abbott, Takeda, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Guerbet, Yakult, Eli Lilly, Kowa, Nippon Kayaku, and Daiichi-Sankyo. NM has received honoraria from Taiho, Eli Lilly, Yakult, Novartis, Pfizer, and Kyowa Hakko Kirin and research funding from Taiho, Merck Serono, AstraZeneca, Zeria, and Takeda. He is also a member of the speakers' bureau for Taiho. KF has received research funding from Taiho. He is also a member of the speakers' bureau for Takeda, Chugai, Ajinomoto, Shionogi, Janssen, and Eli Lilly. MF has received research funding from Taiho. He is also a member of the speakers' bureau for Taiho. HIg has received honoraria from Taiho, Yakult, Eli Lilly, and Mediphysics, and research funding from Taiho, Eisai, and AstraZeneca. KS has received honoraria from Taiho, and research funding from Taiho, Zeria, and Merck Serono. He has served as a consultant for Taiho. He is also a member of the speakers' bureau for Taiho. JF has received honoraria from Chugai, Taiho, Eli Lilly, Bayer, Eisai, Novartis, Ono. Yakult, Takeda, Astellas, Daiichi-Sankyo, Dainippon Sumitomo, Bristol Myers, Nippon Kayaku, Ajinomoto, Meiji, Sanofi, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Hisamitsu, Sandoz, Shionogi, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, and Merck Serono and research funding from Ono, Onco Therapy Science, Yakult, Graxo Smith Kline, Taiho, Takeda, Chugai, Eli Lilly, Sanofi, Bayer, Novartis, Merck Serono, Pfizer, Daiichi-Sankyo, Torii, Nippon Kayaku, and Bristol Myers. He has served as a consultant for Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Zeria, AstraZeneca, Merck Serono, Graxo Smith Kline, Chugai, Taiho, Bayer, Eisai, Yakult, Fujifilm, Boehringer Ingelheim, Kowa, Astellas, Onco Therapy Science, Otsuka, Janssen, Nobelphama, and J-Pharma. KS has received research funding from Taiho, Yakult, Bristol Myers, and Chugai and honoraria from Takeda, Taiho, Yakult, Chugai, Eli Lilly, Bristol Myers, Eisai, Sawai, Hisamitsu, Meiji, and Ono. TI has received honoraria, research funding, and travel and accommodation fees from Taiho. He has served as a consultant for Taiho. He is also a member of the speakers' bureau for Taiho. SN has received honoraria and research funding from Taiho. He is also a member of the speakers' bureau for Taiho. HB has received honoraria from Taiho, and research funding from Taiho, Yakult, Takeda, and Chugai. He has served as a consultant for Taiho. He is also a member of the speakers' bureau for Taiho, Ono, Takeda, and Chugai. YK has received honoraria and research funding from Taiho. He has served as a consultant for Taiho. He is also a member of the speakers' bureau for Taiho. MT has served as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Hisamitsu, AbbVie, Kyorin, Sanofi, Takeda, and Mitsubishi Tanabe. IH has received research funding from Taiho, and honoraria from Taiho, Chugai, Yakult, Daiichi-Sankyo, and Bristol Myers. He has served as a consultant for Taiho, Chugai, Yakult, and Daiichi-Sankyo. NB has received research funding from Taiho and Chugai, and honoraria from Taiho, Chugai, Yakult, and Daiichi-Sankyo. He has served as a consultant for Taiho. He is also a member of the speakers' bureau for Taiho.

references

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011; 61: 69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 1817–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 1691–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oettle H, Riess H, Stieler JM et al. Second-line oxaliplatin, folinic acid, and fluorouracil versus folinic acid and fluorouracil alone for gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer: outcomes from the CONKO-003 trial. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 2423–2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ueno H, Ioka T, Ikeda M et al. Randomized phase III study of gemcitabine plus S-1, S-1 alone, or gemcitabine alone in patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer in Japan and Taiwan: GEST study. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 1640–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morizane C, Okusaka T, Furuse J et al. A phase II study of S-1 in gemcitabine-refractory metastatic pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2009; 63: 313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohkawa S, Okusaka T, Isayama H et al. Randomised phase II trial of S-1 plus oxaliplatin vs S-1 in patients with gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 2015; 112: 1428–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mizuno N, Yamao K, Komatsu Y et al. Randomized phase II trial of S-1 versus S-1 plus irinotecan (IRIS) in patients with gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer. In J Clin Oncol 2013; 31 (Suppl. 4); abstr 263. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thirion P, Michiels S, Pignon JP et al. Modulation of fluorouracil by leucovorin in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: an updated meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 3766–3775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsukioka S, Uchida J, Tsujimoto H et al. Oral fluoropyrimidine S-1 combined with leucovorin is a promising therapy for colorectal cancer: evidence from a xenograft model of folate-depleted mice. Mol Med Rep 2009; 2: 393–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Cutsem E, Findlay M, Osterwalder B et al. Capecitabine, an oral fluoropyrimidine carbamate with substantial activity in advanced colorectal cancer: results of a randomized phase II study. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18: 1337–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koizumi W, Boku N, Yamaguchi K et al. Phase II study of S-1 plus leucovorin in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2010; 21: 766–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denda T, Li J, Xu R et al. Phase II study of S-1 plus leucovorin (a new 1-week treatment regimen followed by a 1-week rest period) in patients with untreated metastatic colorectal cancer in Japan and China. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30 (Suppl. 4): abstr 598. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hironaka S, Sugimoto N, Yamaguchi K et al. S-1 plus leucovorin versus S-1 plus leucovorin and oxaliplatin versus S-1 plus cisplatin in patients with advanced gastric cancer: a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17: 99–108 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang-Gillam A, Li CP, Bodoky G et al. Nanoliposomal irinotecan with fluorouracil and folinic acid in metastatic pancreatic cancer after previous gemcitabine-based therapy (NAPOLI-1): a global, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2015 Nov 29 [epub ahead of print], doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00986-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahma OE, Duffy A, Liewehr DJ et al. Second-line treatment in advanced pancreatic cancer: a comprehensive analysis of published clinical trials. Ann Oncol 2013; 24: 1972–1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prado CM, Baracos VE, McCargar LJ et al. Sarcopenia as a determinant of chemotherapy toxicity and time to tumor progression in metastatic breast cancer patients receiving capecitabine treatment. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15: 2920–2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baumgartner RN, Koehler KM, Romero L, Garry PJ. Serum albumin is associated with skeletal muscle in elderly men and women. Am J Clin Nutr 1996; 64: 552–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.