Abstract

Purpose

To assess and compare the levels of functioning in patients with major depressive disorder treated with either duloxetine with a daily dose of ≤60 mg or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) as monotherapy for up to 6 months in a naturalistic setting in East Asia. In addition, this study examined the impact of painful physical symptoms (PPS) on the effects of these treatments.

Patients and methods

Data for this post hoc analysis were taken from a 6-month prospective observational study involving 1,549 patients with major depressive disorder without sexual dysfunction. The present analysis focused on a subgroup of patients from East Asia (n=587). Functioning was measured using the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS). Depression severity was assessed using the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self Report. PPS were rated using the modified Somatic Symptom Inventory. A mixed model with repeated measures was fitted to compare the levels of functioning between duloxetine-treated (n=227) and SSRI-treated (n=225) patients, adjusting for baseline patient characteristics.

Results

The mean SDS total score was similar between the two treatment cohorts (15.46 [standard deviation =6.11] in the duloxetine cohort and 16.36 [standard deviation =6.53] in the SSRI cohort, P=0.077) at baseline. Both descriptive and regression analyses confirmed improvement in functioning in both groups during follow-up, but duloxetine-treated patients achieved better functioning. At 24 weeks, the estimated mean SDS total score was 4.48 (standard error =0.80) in the duloxetine cohort, which was statistically significantly lower (ie, better functioning) than that of 6.76 (standard error =0.77) in the SSRI cohort (P<0.001). This treatment difference was more apparent in the subgroup of patients with PPS at baseline. Similar patterns were also observed for SDS subscores (work, social life, and family life).

Conclusion

Depressed patients treated with duloxetine achieved better functioning compared to those treated with SSRIs. This treatment difference was mostly driven by patients with PPS at baseline.

Keywords: depression, antidepressant, duloxetine, SSRI, functioning

Introduction

Depression is one of the most prevalent, disabling, and costly mental disorders, currently affecting nearly 350 million people worldwide.1 The Global Burden of Disease 2010 study identified depression as a leading cause of burden, accounting for 40.5% of disability-adjusted life years associated with mental and substance-use disorders.2 The economic burden of depression also appeared to be substantial even in nonwestern countries. For instance, the total costs of depression were estimated to be over US$6 billion in People’s Republic of China (2002 value),3 ¥2 trillion in Japan (2005 value),4 and US$4 million in South Korea (2005 value).5 Notably, morbidity costs, arising from productivity loss due to absenteeism and presenteeism, far exceeded treatment costs of depression in all studies, implying significant impairment in functioning and quality of life in patients with depression.

Indeed, ~60% of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) were reported to have severe functional impairment such as disruption in physical, social, and occupational functioning,6 and a similar proportion of the patients were also reported to have severe impairment in quality of life.7 This evidence reflects a substantial unmet need in the treatment of MDD, especially from a patient’s perspective. Notably, return to a normal level of functioning is often reported by patients as more important than symptom-related outcomes.8 While the importance of normalization of functioning is increasingly recognized in the treatment of MDD, functional outcomes are still frequently excluded when evaluating the effects of MDD treatments. Without functioning assessment, however, the effects of MDD treatments may not be fully captured because functional impairment in patients with MDD often lags behind the resolution of clinical symptoms,9 and more importantly, residual functional impairment could increase the risk of MDD relapse.10–12

Painful physical symptoms (PPS) such as headache, abdominal pain, heart/chest pain, and back pain often accompany the emotional symptoms of MDD; up to 76% of patients with MDD have been reported to have such symptoms,13–17 and the majority of them have also been reported to have multiple pain complaints.18 Not surprisingly, previous research has shown that these symptoms can severely interfere with daily functioning and quality of life in patients with MDD.19,20 Return to normal functioning in MDD could therefore be heavily influenced by the extent of PPS control.20

Duloxetine hydrochloride is a potent and relatively balanced inhibitor of a potent and relatively balanced serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI).21 It has been approved for the management of MDD, generalized anxiety disorder, fibromyalgia, diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain (DPNP), and chronic musculoskeletal pain in the United States, and also for the management of some or all of the indications in many other countries worldwide, including Asian countries, most recently in Japan (for MDD and DPNP). The findings from clinical trials have shown that treatment with duloxetine improves clinical outcomes in patients with MDD.22–24 In particular, in line with its pain-related indications, the effects of duloxetine, compared to other classes of antidepressants, have been found to be more apparent in a subgroup of MDD patients with PPS.25–27 It has been suggested that the dual action of SNRIs may be more effective than those that inhibit only one monoamine at least for patients suffering from both depression and pain,25–27 given the hypothesis that the pathophysiology of both conditions involves an imbalance of serotonin and norepinephrine.15 Nevertheless, more research is warranted to determine the relative effects of SNRIs and other classes of antidepressants at least in this subgroup.

The present post hoc analysis examined the course of impaired functioning during the treatment of patients with MDD and compared the level of functioning in patients treated with duloxetine or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) for up to 6 months in a naturalistic setting in East Asia, using data from a 6-month prospective observational study. Functioning was measured using the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), which is a brief self-report inventory that assesses functional impairment in work/school, social life, and family life.28 It is believed to be one of the most effective measures of functional impairment because of its sensitivity in detecting treatment effects and its ease of use.29 In Japan, the daily dose of duloxetine is limited to a maximum of 60 mg/day for the treatment of MDD. Although our study did not include Japan, we also limited the maximum dose of duloxetine to 60 mg/day to ensure that our results have broader implications across East Asia including Japan. In addition, given the link between pain and functional impairment, we also performed subgroup analyses for patients with and without PPS at baseline to examine whether treatment effects on functioning vary by PPS status.

Patients and methods

Data and study sample

Data for this post hoc analysis were taken from a 6-month, international, prospective, noninterventional, observational study, primarily designed to examine treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction and other treatment outcomes among patients with MDD who were treated with either an SSRI or an SNRI in actual clinical practice. A total of 1,647 patients were enrolled at 88 sites between November 15, 2007, and November 28, 2008. Of these, 1,549 patients were classified as “sexually active patients without sexual dysfunction at study entry” and included in the study. The present analysis focused only on those patients from East Asia (n=587) (People’s Republic of China [n=205; 13.2%], Hong Kong [n=18; 1.2%], Malaysia [n=33; 2.1%], the Philippines [n=113; 7.3%], Taiwan [n=199; 12.8%], Thailand [n=17; 1.1%], and Singapore [n=2; 0.1%]).

Patients (outpatients) were eligible to participate in the study if they met the following inclusion criteria: 1) presenting with an episode of MDD within the normal course of care, with MDD diagnosed according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10)30 or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-4th edition text revision (DSM-IV-TR)31 criteria; 2) at least moderately depressed, defined by the Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S) (with a score of ≥4);32 3) initiating or switching to any available SSRI or SNRI antidepressant, in accordance with a treating psychiatrist’s discretion; 4) at least 18 years of age; 5) sexually active (with partner or autoerotic activity, including during the 2 weeks prior to study entry) without sexual dysfunction, as defined by Arizona Sexual Experience Scale;33 6) not participating in another currently ongoing study; and 7) providing consent to release data. The study excluded patients who had: 1) a history of treatment-resistant depression; 2) a past or current diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform, or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, dysthymia, mental retardation, or dementia; or 3) received any antidepressant within 1 week (1 month for fluoxetine) prior to study entry, with the exception of patients receiving an ineffective treatment for whom the immediate switch to an SSRI or SNRI antidepressant was considered to be the best treatment option.

Ethical approval

This study followed the ethical standards of responsible local committees and the regulations of the participating countries. Ethical Review Board (ERB) approval was obtained as required for observational studies wherever required by local law. The review boards included can be found in the Supplementary material.

All patients also provided written informed consent for the provision and collection of the data. Further details of the study design have been published elsewhere.34–36

Study therapy

Patients were prescribed any commercially available SSRI or SNRI in accordance with each country’s approved labels and at the discretion of the participating psychiatrist. Patients were not required to continue taking the medication initiated at baseline. Changes in medication and dosing were possible at any time as determined by the treating psychiatrist.

The present analysis included only those patients who initiated either duloxetine with a daily dose of ≤60 mg (duloxetine cohort) or an SSRI (SSRI cohort) at approved therapeutic dosages, both as monotherapy at baseline.

Data collection and outcome assessment

Data collection for the study occurred during visits within the normal course of care. The routine outpatient visit at which patients were enrolled served as the time for baseline data collection. Subsequent data collection was targeted at week 8, week 16, and week 24 since the baseline visit. Patient demographics and clinical history were recorded at the baseline assessment. Clinical severity of depression was assessed at each visit using the CGI-S32 and the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report (QIDS-SR16).37

Functioning was also assessed at each visit using the SDS, which is a brief self-report inventory that assesses functional impairment in work/school, social life, and family life.28 The level of functioning in each of the three domains was measured from 0 to 10 (0: no impairment, 1–3: mild impairment, 4–6: moderate impairment, 7–9: marked impairment, 10: extreme impairment). The level of global functioning was measured with the sum of the three subscores.

Depression-related pain severity was measured using the pain-related items of the Somatic Symptom Inventory (SSI), which included abdominal pain, lower back pain, joint pain, neck pain, heart/chest pain, headaches, and muscular soreness.38 PPS status was also assessed as PPS negative (PPS−) or positive (PPS+); PPS+ was defined as a mean score of ≥2 for the seven pain-related items of the SSI.

Statistical analysis

This study included a total of 452 patients who 1) initiated either duloxetine with a daily dose of ≤60 mg or an SSRI as monotherapy at baseline for the treatment of MDD and 2) who did not have missing data on the QIDS-SR16 score at baseline with at least one nonmissing QIDS-SR16 score during follow-up (n=227 in the duloxetine group and n=225 in the SSRI group). It also analyzed the patient observations up to the point where their initial medications were discontinued (n=176 [77.5%] in the duloxetine group and n=167 [74.2%] in the SSRI group available at 24 weeks).

Baseline patient characteristics as well as outcomes at each visit by initial treatments were described and compared using the chi-square test (for categorical variables) and Mann–Whitney test (for continuous variables).

The mean levels (raw values) of functioning (both total and subscores of the SDS) at each visit by treatment in the overall sample as well as in the subgroup of patients with PPS+ and PPS−, respectively, were also described and compared using the Mann–Whitney test. The effect sizes were also calculated using Cohen’s d (ie, the difference in mean values divided by a standard deviation)39 for the differences in the levels of functioning between the two treatment cohorts at each visit.

Adjusted mixed-effects modeling with repeated measures (MMRM) analysis was used to compare levels of functioning (SDS total, work, social life, and family life) during follow-up between the two treatment cohorts. The unstructured covariance pattern was used to model within-patient correlation. These models were adjusted for age, sex, SSI pain score at baseline, QIDS-SR16 score at baseline, the baseline value of the outcome modeled, and visit number. In addition, the following variables were included for further adjustment if they appeared to be significant (P<0.1) in univariate analyses: independent living (living in his/her own house), living with a spouse/partner, employment status, having MDD episodes in the 24 months prior to study entry, MDD hospitalizations in the 24 months prior to study entry, and the number of any significant preexisting comorbidities. Finally, the models also included the interaction term between time (visit number) and treatment if it appeared to be significant (P<0.05) in the full model.

All analyses were repeated for subgroups of patients with and without PPS (ie, PPS+ and PPS− patients) to examine whether treatment effects on functioning vary by PPS status at baseline.

The differences between the two treatment cohorts were considered statistically significant with a P-value of <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.3 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics at study entry

A total of 452 patients were included in the final analysis. Overall, the mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of these patients was 37.5 (SD =10.8) years and 56.0% were female. More than one-third of the patients were from People’s Republic of China (n=165, 36.5%), followed by Taiwan (n=122, 27.0%) and the Philippines (n=108, 23.9%). In addition, almost half of the patients (n=201, 44.6%) had PPS at baseline.

Of the 452 patients, 227 initiated duloxetine with a daily dose of ≤60 mg at baseline and the rest (n=225) initiated an SSRI antidepressant at baseline. The most common SSRIs prescribed at baseline were paroxetine (29.3%), fluoxetine (23.6%), escitalopram (20.0%), and sertraline (12.9%). The median daily doses of these medications at baseline were 20.0 mg/day for paroxetine, 10.0 mg/day for escitalopram, 50.0 mg/day for sertraline, 20.0 mg/day for fluoxetine, and 60.0 mg/day for duloxetine.

Table 1 summarizes the baseline patient characteristics by treatment cohorts. While sociodemographic characteristics were in general similar between the two cohorts, a higher proportion of the SSRI cohort was from People’s Republic of China. In addition, a lower proportion of them had PPS at baseline (51.1% in the duloxetine cohort and 37.9% in the SSRI cohort, P=0.005), and the mean SSI pain score at baseline was also lower in the SSRI cohort than in the duloxetine cohort. Nevertheless, the level of depression severity, as measured by CGI-S and QIDS-SR16, was similar between the two cohorts.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics by treatment cohorts

| Baseline characteristics | Duloxetine (≤60 mg per day) (n=227) | SSRI (n=225) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 37.7 (10.7) | 37.4 (11.0) | 0.712 |

| Female, % | 59.5 | 52.4 | 0.132 |

| Country, % | <0.001 | ||

| Hong Kong | 0.4 | 6.2 | |

| Malaysia | 7.0 | 7.1 | |

| Thailand | 0.0 | 3.6 | |

| Singapore | 0.0 | 0.9 | |

| Taiwan | 30.8 | 23.1 | |

| People’s Republic of China | 26.0 | 47.1 | |

| Philippines | 35.7 | 12.0 | |

| Age at first symptoms of MDD, mean (SD) | 35.5 (10.9) | 34.7 (11.3) | 0.403 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 22.8 (3.5) | 22.5 (3.2) | 0.315 |

| Living with a spouse/partner, % | 64.6 | 71.1 | 0.139 |

| CGI-S, mean (SD) | 4.3 (0.6) | 4.4 (0.6) | 0.092 |

| QIDS-SR16, mean (SD) | 14.0 (4.4) | 14.2 (4.3) | 0.622 |

| SSI-pain, mean (SD) | 14.5 (5.3) | 12.8 (4.4) | 0.001 |

| Painful physical symptoms, % | 51.1 | 37.9 | 0.005 |

| Number of comorbidities, % | 0.353 | ||

| None | 86.8 | 82.6 | |

| 1 | 8.4 | 12.5 | |

| ≥2 | 4.8 | 4.9 | |

| Had MDD episodes in the past 24 months, % | 56.4 | 57.8 | 0.765 |

| Had been hospitalized for MDD in the past 24 months, % | 4.0 | 8.0 | 0.070 |

Note: Data are presented as percentage or mean (SD) as appropriate.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions of Severity; MDD, major depressive disorder; QIDS-SR16, 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report; SD, standard deviation; SSI-pain, Somatic Symptom Inventory; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Improvement in functioning by treatment cohort

Table 2 demonstrates the levels of functioning (raw means), as measured by SDS total and subscores, at baseline and at 24 weeks by treatment cohort. The levels of functional impairment were generally similar between the two treatment cohorts at baseline: the mean SDS total score at baseline was 15.46 (SD =6.11) in the duloxetine cohort and 16.36 (SD =6.53) in the SSRI cohort (P=0.077). Specifically, both treatment cohorts, on average, exhibited a moderate level of functional impairment at baseline in all three inter-related domains (SDS work, social life, and family life), with the mean score of 4.91 (SD =2.30) (for family life) to 5.33 (SD =2.28) (for work) in the duloxetine cohort and that of 5.31 (SD =2.53) (for family life) to 5.54 (SD =2.45) (for work) in the SSRI cohort. While the mean SDS total score at baseline was also similar between the two treatment cohorts in the subgroup of PPS+ patients (16.76 [SD =6.35] in the duloxetine cohort and 16.96 [SD =7.11] in the SSRI cohort, P=0.546), it was slightly higher in the SSRI cohort in the subgroup of PPS− patients (14.09 [SD =5.56] in the former and 16.01 [SD =6.18] in the latter, P=0.013).

Table 2.

Mean levels (raw values) of SDS total and subscores at baseline and at 24 weeks by treatment cohorts with and without PPS at baseline

| Outcome | Total

|

PPS+

|

PPS−

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duloxetine | SSRI | Effect sizesa | Duloxetine | SSRI | Effect sizesa | Duloxetine | SSRI | Effect sizesa | |

| At baseline | |||||||||

| SDS total score | 15.46 (6.11) | 16.36 (6.53) | −0.14 | 16.76 (6.35) | 16.96 (7.11) | −0.03 | 14.09 (5.56)b | 16.01 (6.18)b | −0.33 |

| SDS work score | 5.33 (2.28) | 5.54 (2.45) | −0.10 | 5.52 (2.39) | 5.59 (2.55) | −0.03 | 5.13 (2.16) | 5.52 (2.40) | −0.17 |

| SDS social life score | 5.20 (2.22) | 5.48 (2.49) | −0.12 | 5.59 (2.29) | 5.62 (2.65) | −0.01 | 4.80 (2.09)b | 5.39 (2.39)b | −0.26 |

| SDS family life score | 4.91 (2.30)b | 5.31 (2.53)b | −0.17 | 5.63 (2.22) | 5.65 (2.68) | −0.01 | 4.16 (2.16)b | 5.11 (2.42)b | −0.41 |

| At 24 weeks | |||||||||

| SDS total score | 2.15 (4.35)b | 4.69 (4.88)b | −0.55 | 1.95 (4.19)b | 5.48 (5.61)b | −0.75 | 2.35 (4.54)b | 4.37 (4.55)b | −0.44 |

| SDS work score | 0.75 (1.48)b | 1.74 (1.69)b | −0.62 | 0.66 (1.37)b | 1.93 (1.70)b | −0.85 | 0.83 (1.59)b | 1.67 (1.69)b | −0.51 |

| SDS social life score | 0.75 (1.48)b | 1.47 (1.66)b | −0.46 | 0.69 (1.43)b | 1.70 (1.97)b | −0.62 | 0.81 (1.53)b | 1.38 (1.51)b | −0.38 |

| SDS family life score | 0.66 (1.48)b | 1.44 (1.68)b | −0.49 | 0.60 (1.46)b | 1.70 (1.87)b | −0.68 | 0.71 (1.49)b | 1.33 (1.60)b | −0.40 |

Notes:

These show effect sizes of differences in functional impairment between treatment cohorts.

P<0.05 for the comparison of the outcome between the duloxetine cohort and the SSRI cohort in the overall sample, PPS+ patients, and PPS− patients, respectively. Data are presented as mean (standard deviation).

Abbreviations: PPS, painful physical symptoms; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Despite similar levels of functioning at baseline between the two treatment cohorts in the overall sample as well as in the subgroup of PPS+ patients, duloxetine-treated patients achieved greater levels of functioning at 24 weeks, compared to SSRI-treated patients. The mean SDS total score at 24 weeks was 2.15 (SD =4.35) in the duloxetine cohort and 4.69 (SD =4.88) in the SSRI cohort in the overall sample (P<0.001). The effect size of this treatment difference was −0.55. A higher level of functioning in the duloxetine cohort was also observed in all three SDS domains (work, social life, and family life) with the effect sizes of −0.46 (social life) to −0.62 (work). The treatment difference was more apparent in the subgroup of PPS+ patients. The mean SDS total score at 24 weeks was 1.95 (SD =4.19) in the duloxetine cohort and 5.48 (SD =5.61) in the SSRI cohort in this subgroup (P<0.001), resulting in the effect size of −0.75. Similarly, a higher level of functioning in the duloxetine cohort was also observed in all three SDS domains, with the effect sizes of −0.62 (social life) to −0.85 (work). Meanwhile, the treatment difference at 24 weeks in the subgroup of PPS− patients was similar to that observed at baseline, although both treatment cohorts achieved better functioning at 24 weeks. The mean SDS total score at 24 weeks was 2.35 (SD =4.54) in the duloxetine cohort and 4.37 (SD =4.55) in the SSRI cohort in this subgroup (P<0.001).

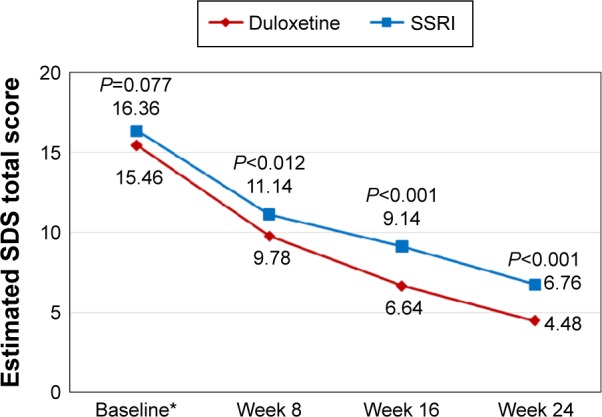

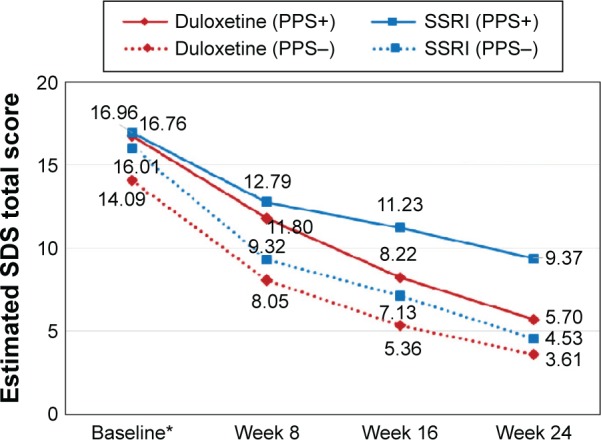

The superiority of duloxetine over SSRIs in terms of improvement in functioning was maintained even when the baseline differences between the two treatment cohorts were adjusted for (Figure 1). Given the interaction term between time and treatment included in the MMRM models (Table 3), the interpretation of the coefficients of treatment, time, and their interaction was not straightforward. Therefore, the (adjusted) mean SDS total scores (ie, least squares means) at each postbaseline visit by treatment cohorts were further estimated and presented in Figure 1. Consistent with the descriptive results, the MMRM results also showed higher levels of functioning in duloxetine-treated patients than in SSRI-treated patients throughout follow-up (P<0.05 for all treatment comparisons at each postbaseline visit). At 24 weeks, the estimated mean SDS total score was 4.48 (standard error [SE] =0.80) in the duloxetine cohort, which was lower than that of 6.76 (SE =0.77) in the SSRI cohort (P<0.001) (ie, better functioning in the duloxetine cohort). As shown in Figure 2, the treatment difference, especially at latter follow-up visits, was again more apparent in the subgroup of PPS+ patients, whereas the treatment difference at baseline observed in the subgroup of PPS− patients remained relatively constant throughout follow-up in this subgroup. Similar patterns were observed in each of SDS domains (ie, work, social life, and family life) (data not shown).

Figure 1.

The estimated SDS total scores during follow-up by treatment cohorts.

Note: *The baseline scores are raw mean values.

Abbreviations: SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Table 3.

The results of MMRM analyses: factors associated with SDS total scores during follow-up

| Parameter | Parameter estimate | Standard error | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.355 | 1.276 | 0.001 |

| Age | −0.001 | 0.020 | 0.957 |

| Female (vs male) | 0.218 | 0.432 | 0.614 |

| QIDS-SR16 score at baseline | −0.056 | 0.063 | 0.375 |

| SSI-pain score at baseline | 0.010 | 0.048 | 0.842 |

| SDS total score at baseline | 0.312 | 0.042 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities (vs none) | |||

| 1 | 0.969 | 0.782 | 0.216 |

| ≥2 | 0.813 | 1.294 | 0.530 |

| Had been hospitalized in the 24 months prior to baseline | 3.441 | 1.213 | 0.005 |

| Had MDD episodes in the 24 months prior to baseline | 0.500 | 0.443 | 0.259 |

| Duloxetine (vs SSRI) | −1.361 | 0.536 | 0.012 |

| Weeks (vs week 8) | |||

| Week 16 | −1.997 | 0.381 | <0.001 |

| Week 24 | −4.376 | 0.441 | <0.001 |

| Weeks × treatments | |||

| Duloxetine at week 16 | −1.139 | 0.527 | 0.031 |

| Duloxetine at week 24 | −0.918 | 0.612 | 0.134 |

Abbreviations: MDD, major depressive disorder; MMRM, mixed-effects modeling with repeated measures; QIDS-SR16, 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale; SSI, Somatic Symptom Inventory; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Figure 2.

The estimated SDS total scores during follow-up by treatment cohorts in patients with and without PPS at baseline.

Notes: P=0.546 for the difference in SDS total scores between the two treatment cohorts at baseline and P<0.001 at 24 weeks in the subgroup of PPS+ patients. P=0.013 at baseline and P=0.168 at 24 weeks in the subgroup of PPS− patients. *The baseline scores are raw mean values.

Abbreviations: SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale; PPS, painful physical symptoms; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Discussion

This post hoc analysis examined functioning in the subgroup of East Asian patients who were either treated with duloxetine with a daily dose of ≤60 mg or an SSRI for MDD for up to 6 months in actual clinical practice. The results showed that while this group of patients, on average, exhibited a moderate level of functional impairment in all three interrelated SDS domains (work, social life, and family life) at baseline, their functioning improved substantially in all three domains during follow-up. In particular, duloxetine-treated patients achieved greater improvement in functioning compared to SSRI-treated patients. This treatment difference was mostly driven by the subgroup of patients with PPS at baseline.

Effects of antidepressants on functioning

No published research has examined the comparative effectiveness of duloxetine (or SNRIs) and SSRIs on functioning in patients with MDD. Recently, however, several studies have examined the effects of antidepressants, mostly SNRIs, versus placebo on functioning.11,40–46 These studies, in general, have demonstrated greater effects of antidepressants compared to placebo, especially in subgroups of patients with MDD such as those with PPS or severely ill. Using pooled data from six randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in patients with MDD, Mancini et al40 reported the treatment difference of −2.52 between duloxetine and placebo in the SDS total score at the short-term end point (7–13 weeks), which was statistically significant in favor of duloxetine. More interestingly, they also presented the results of path analysis, which indicated that the effects of duloxetine on functioning is mainly mediated through its effect on depressive symptoms, as measured using the Hamilton rating scale for depression (HAMD),47 and PPS, as measured using a visual analog scale for pain severity (each ~40% of the total effect on functioning). This finding also partly explains the additional advantage of duloxetine on functioning in PPS+ patients observed in our study. The impact of depression and pain on functioning has also been demonstrated in another duloxetine study. Using data from a single-arm open-label study, this study assessed the relationship between functional improvement in the SDS total score and clinical outcomes of mood, pain, and anxiety >8 weeks after switching treatment to duloxetine in patients with MDD.48 The study showed significant improvement in functioning after switching to duloxetine. Such functional improvement appeared to be positively correlated with each of the clinical outcomes, but more so with mood and pain than with anxiety. The effects of duloxetine on functioning in patients with MDD were, however, challenged in an analysis of two clinical trials having similar protocols and comparable patient populations.41 Duloxetine appeared to be superior to placebo in improving the 17-item HAMD (HAMD17) work/activities scores at week 8 in one trial but not in another, although it narrowly missed statistical significance in the latter (P=0.051).

There are also a few studies that have demonstrated the effects of the SNRIs levomilnacipran,42 venlafaxine,11 and desvenlafaxine43,44,46 on several types of functional outcomes in patients with MDD. Notably, the superiority of desvenlafaxine over placebo on functioning was better observed in more severely ill patients. For instance, the superiority of desvenlafaxine was not observed in the whole sample (P=0.067) but observed in the subgroup of more severely ill patients with MDD (P=0.017) in a 12-week RCT.43 Meanwhile, few studies have examined the effects of SSRIs on functioning.45 Kocsis et al45 assessed long-term, maintenance psychosocial functioning in patients with chronic major and double depression. The patients included in this maintenance phase were those identified as responders at the end of prior 16-week continuous treatment with the SSRI sertraline. While long-term treatment with sertraline resulted in only modest additional improvement of psychosocial functioning over that achieved in the short-term phase, those taking placebo experienced substantial worsening in psychosocial functioning compared to those taking sertraline during the maintenance phase.

Comparative effectiveness of antidepressants and role of depression-related pain

The superiority of SNRIs, including duloxetine over SSRIs, in terms of other clinical outcomes, has not been well established in the literature either. There is, however, limited evidence to support the additional advantage of SNRIs in subgroups of patients with MDD with PPS and/or more severely ill.

First of all, the findings of the previous study with the same data as those employed here demonstrated greater effects of duloxetine than SSRIs in terms of remission, response, and depressive symptoms, especially in patients with PPS at baseline.36 Notably, this study (thereby the present analysis as well) included those patients who were at least moderately depressed, defined by the CGI-S score of ≥4.

Similarly, Thase et al,26 using pooled data from six RCTs, found that although duloxetine and the two SSRIs (fluoxetine and paroxetine) were comparably efficacious overall, treatment with duloxetine was associated with higher remission rate in patients with moderate-to-severe depression (a HAMD17 score of ≥19). Similar findings were also reported with another SNRI, milnacipran, in Japan. A case–control comparison of milnacipran and the SSRI fluvoxamine in 202 outpatients with major depression in Japan found that although the overall response rates were similar between the two groups, there were significantly more responders in the milnacipran group than in the fluvoxamine group in more severely depressed patients (a HAMD17 score of >19) as well as in patients with high scores on the “agitation” and “insomnia” items of the HAMD17.49 In addition to these comparative studies, several placebo-controlled duloxetine studies have demonstrated its effects on controlling depression-related PPS,22–24 as also reflected in its treatment indications, such as fibromyalgia, DPNP, and chronic musculoskeletal pain approved in the United States as well as in many other countries worldwide. Such studies are rarely available for SSRIs.

Taken together, continuous treatment is important to maintain functional well-being in patients with MDD. There seems a clear link between depression-related pain and functional impairment. SNRIs, duloxetine in particular, may better help patients with MDD to return to a normal level of daily functioning, than SSRIs, at least in the subgroup of patients with PPS or more severely ill.

Study limitations

These results should be interpreted in the context of the following study limitations. First, the data were drawn from an observational study. Although the MMRM analysis controlled the baseline imbalance between the two treatment cohorts, it is not possible to control any unobserved imbalance between the two cohorts. Second, as the primary objective of this observational study was to assess the frequency of treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction in the treatment of MDD, the study included only those patients who were sexually active without sexual dysfunction at baseline. Sexual dysfunction has been reported to be two to three times more prevalent in patients with depression compared to the general population,50,51 and thus, our findings may not be immediately generalizable to patients with MDD as a whole. Further research is warranted to examine whether these findings can be replicated in patients with MDD without such inclusion/exclusion criteria. Third, although this observational study included >500 patients from East Asia, they may not be representative of patients with MDD in the region as a whole. Finally, a multiplicity of analyses was not adjusted for in these exploratory analyses. Our results therefore should be interpreted with caution until further replication is available.

Conclusion

Patients treated with duloxetine with a daily dose of ≤60 mg achieved higher levels of functioning (ie, global, work, social life, and family life), compared to those treated with SSRIs for the management of MDD in actual clinical practice settings in East Asia. As hypothesized, the superiority of duloxetine over SSRIs on functional outcomes appeared to be more pronounced in the subgroup of patients with PPS at baseline. This finding reaffirms the importance of pain management in the treatment of MDD, especially for MDD-related functional impairment, and also the additional advantage of duloxetine, possibly SNRIs as a whole, in the treatment of patients with MDD presenting with PPS.

Acknowledgments

The study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Diego Novick, William Montgomery, Héctor Dueñas, and Li Yue are employees of Eli Lilly and Company. Josep Maria Haro has acted as a consultant, received grants, or acted as a speaker in activities sponsored by the following companies: Astra-Zeneca, Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, and Lundbeck. Maria Victoria Moneta conducted the statistical analysis under a contract between Fundació Sant Joan de Déu and Eli Lilly and Company. Gang Zhu has acted as a consultant. Jihyung Hong has been a consultant for Eli Lilly and Company. Roberto Brugnoli has acted as a consultant, received grants, or acted as a speaker in activities sponsored by the following companies: BMS, Eli Lilly, Innovapharma, and Sigma-Tau. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.WHO. [webpage on the internet] Depression. 2012. [Accessed January 10, 2016]. [updated on October 2015]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/

- 2.Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1575–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu TW, He Y, Zhang M, Chen N. Economic costs of depression in China. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(2):110–116. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sado M, Yamauchi K, Kawakami N, et al. Cost of depression among adults in Japan in 2005. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65(5):442–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang SM, Hong JP, Cho MJ. Economic burden of depression in South Korea. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(5):683–689. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. National Comorbidity Survey Replication The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rapaport MH, Clary C, Fayyad R, Endicott J. Quality-of-life impairment in depressive and anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(6):1171–1178. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmerman M, McGlinchey JB, Posternak MA, Friedman M, Attiullah N, Boerescu D. How should remission from depression be defined? The depressed patient’s perspective. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):148–150. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKnight PE, Kashdan TB. The importance of functional impairment to mental health outcomes: a case for reassessing our goals in depression treatment research. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(3):243–259. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solomon DA, Leon AC, Endicott J, et al. Psychosocial impairment and recurrence of major depression. Compr Psychiatry. 2004;45(6):423–430. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trivedi MH, Dunner DL, Kornstein SG, et al. Psychosocial outcomes in patients with recurrent major depressive disorder during 2 years of maintenance treatment with venlafaxine extended release. J Affect Disord. 2010;126(3):420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vittengl JR, Clark LA, Jarrett RB. Deterioration in psychosocial functioning predicts relapse/recurrence after cognitive therapy for depression. J Affect Disord. 2009;112(1–3):135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirmayer L, Robbins J, Dworkind M, Yaffe MJ. Somatization and the recognition of depression and anxiety in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(5):734–741. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.5.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corruble E, Guelfi JD. Pain complaints in depressed inpatients. Psychopathology. 2000;33(6):307–309. doi: 10.1159/000029163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(20):2433–2445. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Eckert GJ, Stang PE, Croghan TW, Kroenke K. Impact of pain on depression treatment response in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(1):17–22. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000106883.94059.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munoz RA, McBride ME, Brnabic AJ, et al. Major depressive disorder in Latin America: the relationship between depression severity, painful somatic symptoms, and quality of life. J Affect Disord. 2005;86(1):93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaccarino AL, Sills TL, Evans KR, Kalali AH. Multiple pain complaints in patients with major depressive disorder. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(2):159–162. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181906572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnow BA, Hunkeler EM, Blasey CM, et al. Comorbid depression, chronic pain, and disability in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(2):262–268. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000204851.15499.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demyttenaere K, Reed C, Quail D, et al. Presence and predictors of pain in depression: results from the FINDER study. J Affect Disord. 2010;125(1–3):53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.02.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bymaster FP, Lee TC, Knadler MP, Detke MJ, Iyengar S. The dual transporter inhibitor duloxetine: a review of its preclinical pharmacology, pharmacokinetic profile, and clinical results in depression. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11(12):1475–1493. doi: 10.2174/1381612053764805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson MJ, Sheehan D, Gaynor PJ, et al. Relationship between major depressive disorder and associated painful physical symptoms: analysis of data from two pooled placebo-controlled, randomized studies of duloxetine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;28(6):330–338. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e328364381b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brecht S, Courtecuisse C, Debieuvre C, et al. Efficacy and safety of duloxetine 60 mg once daily in the treatment of pain in patients with major depressive disorder and at least moderate pain of unknown etiology: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(11):1707–1716. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fava M, Mallinckrodt CH, Detke MJ, Watkin JG, Wohlreich MM. The effect of duloxetine on painful physical symptoms in depressed patients: do improvements in these symptoms result in higher remission rates? J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(4):521–530. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papakostas GI, Thase ME, Fava M, Nelson JC, Shelton RC. Are antidepressant drugs that combine serotonergic and noradrenergic mechanisms of action more effective than the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treating major depressive disorder? A meta-analysis of studies of newer agents. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62(11):1217–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thase ME, Pritchett YL, Ossanna MJ, Swindle RW, Xu J, Detke MJ. Efficacy of duloxetine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: comparisons as assessed by remission rates in patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(6):672–676. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e31815a4412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thase ME, Entsuah AR, Rudolph RL. Remission rates during treatment with venlafaxine or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:234–241. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheehan DV. The Anxiety Disease. New York, NY: Scribner’s; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bech P. Social functioning: should it become an endpoint in trials of antidepressants? CNS Drugs. 2005;19(4):313–324. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200519040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO . The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 31.APA . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2000. Text revision. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology (Revised) Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGahuey CA, Gelenberg AJ, Laukes CA, et al. The Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX): reliability and validity. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(1):25–40. doi: 10.1080/009262300278623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duenas H, Brnabic AJM, Lee A, et al. Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction with SSRIs and duloxetine: effectiveness and functional outcomes over a 6-month observational period. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2011;15(4):242–254. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2011.590209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duenas H, Lee A, Brnabic AJM, et al. Frequency of treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction and treatment effectiveness during SSRI or duloxetine therapy: 8-week data from a 6-month observational study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2011;15(2):80–90. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2011.572169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hong J, Novick D, Montgomery W, et al. Real-world outcomes in patients with depression treated with duloxetine or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in East Asia. Asia Pac Psychiatry. doi: 10.1111/appy.12178. Epub 2015 Mar 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Physical symptoms in primary care. Predictors of psychiatric disorders and functional impairment. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3(9):774–779. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.9.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Eribaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mancini M, Sheehan DV, Demyttenaere K, et al. Evaluation of the effect of duloxetine treatment on functioning as measured by the Sheehan disability scale: pooled analysis of data from six randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical studies. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(6):298–309. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3283589a3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oakes TM, Myers AL, Marangell LB, et al. Assessment of depressive symptoms and functional outcomes in patients with major depressive disorder treated with duloxetine versus placebo: primary outcomes from two trials conducted under the same protocol. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(1):47–56. doi: 10.1002/hup.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sambunaris A, Gommoll C, Chen C, Greenberg WM. Efficacy of levomilnacipran extended-release in improving functional impairment associated with major depressive disorder: pooled analyses of five double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(4):197–205. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunlop BW, Reddy S, Yang L, Lubaczewski S, Focht K, Guico-Pabia CJ. Symptomatic and functional improvement in employed depressed patients: a double-blind clinical trial of desvenlafaxine versus placebo. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(5):569–576. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31822c0a68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lam RW, Endicott J, Hsu MA, Fayyad R, Guico-Pabia C, Boucher M. Predictors of functional improvement in employed adults with major depressive disorder treated with desvenlafaxine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(5):239–251. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kocsis JH, Schatzberg A, Rush AJ, et al. Psychosocial outcomes following long-term, double-blind treatment of chronic depression with sertraline vs placebo. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(8):723–728. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soares CN, Kornstein SG, Thase ME, Jiang Q, Guico-Pabia CJ. Assessing the efficacy of desvenlafaxine for improving functioning and well-being outcome measures in patients with major depressive disorder: a pooled analysis of 9 double-blind, placebo-controlled, 8-week clinical trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(10):1365–1371. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05133blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sheehan DV, Chokka PR, Granger RE, Walton RJ, Raskin J, Sagman D. Clinical and functional outcomes in patients with major depressive disorder and painful physical symptoms switched to treatment with duloxetine. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2011;26(3):242–251. doi: 10.1002/hup.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fukuchi T, Kanemoto K. Differential effects of milnacipran and fluvoxamine, especially in patients with severe depression and agitated depression: a case-control study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;17(2):53–58. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Angst J. Sexual problems in healthy and depressed persons. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998;13(suppl 6):S1–S4. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199807006-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bonierbale M, Lancon C, Tignol J. The ELIXIR study: evaluation of sexual dysfunction in 4557 depressed patients in France. Curr Med Res Opin. 2003;19(2):114–124. doi: 10.1185/030079902125001461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]