Abstract

Although the antioxidant and cardioprotective effects of NecroX-5 on various in vitro and in vivo models have been demonstrated, the action of this compound on the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation system remains unclear. Here we verify the role of NecroX-5 in protecting mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation capacity during hypoxia-reoxygenation (HR). Necrox-5 treatment (10 µM) and non-treatment were employed on isolated rat hearts during hypoxia/reoxygenation treatment using an ex vivo Langendorff system. Proteomic analysis was performed using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and non-labeling peptide count protein quantification. Real-time PCR, western blot, citrate synthases and mitochondrial complex activity assays were then performed to assess heart function. Treatment with NecroX-5 during hypoxia significantly preserved electron transport chain proteins involved in oxidative phosphorylation and metabolic functions. NecroX-5 also improved mitochondrial complex I, II, and V function. Additionally, markedly higher peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1α (PGC1α) expression levels were observed in NecroX-5-treated rat hearts. These novel results provide convincing evidence for the role of NecroX-5 in protecting mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation capacity and in preserving PGC1α during cardiac HR injuries.

Keywords: Hypoxia, Mitochondria, NecroX, Oxidative phosphorylation, PCG1α

INTRODUCTION

Myocardial ischemia (MI) results from reduced blood flow to the heart. MI may damage the heart muscle and in severe cases may cause heart failure and sudden death. Reperfusion-blood resupply to the cardiac muscle-may reduce myocardial damage and therefore is the first choice treatment for patients suffering from MI. Nevertheless, reperfusion itself results in widespread oxidative modifications to lipids and proteins and causes mitochondrial damage, which can eventually cause further myocardial injury [1]. Potential mediators of ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury play roles in oxidative stress, intracellular and mitochondrial Ca2+ overload, and the accumulation of inflammatory cells in the infarcted myocardial tissue [1,2,3]. A recent trend in the application of reperfusion therapy is targeted drug delivery to the affected site [4,5].

Emerging evidence has demonstrated that preservation of mitochondrial function is important for limiting myocardial damage in ischemic heart diseases [6,7,8,9]. Activation of mitochondrial biogenesis, a complex process involving the coordinated expression of mitochondrial and nuclear genes, is a nature-adaptive reaction designed to restore mitochondrial function under ischemic conditions [10]. Alteration of mitochondrial biogenesis is associated with changes in mitochondrial bioenergetics, including alterations in the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system, mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), mitochondrial oxygen consumption, and ATP production. Additionally, almost every functional aspect of OXPHOS strongly influences mitochondrial respiration [6]. Transcription factors regulating the expression of major OXPHOS proteins play important roles in modifying cardiac energy metabolism [11]. One of the most well-known of these transcription factors is peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1α (PGC1α) [12]. Studies have demonstrated decreased PGC1α expression levels during myocardial infarction [13,14], and treatment with metformin [14] or losartan [13] can reduce IR injuries with significant increases in PGC1α expression levels and enhancement of left ventricular function.

Recently, we developed NecroX compounds, cell-permeable necrosis inhibitors with antioxidant activity that localize mainly in the mitochondria [15]. One of these NecroX derivatives, NecroX-5 (C25H31N3O3S·2CH4O3S; molecular weight 453.61 kDa), when administered during hypoxia, strongly protects rat heart mitochondria against reperfusion injury by reducing mitochondrial oxidative stress, preserving the ΔΨm, improving mitochondrial oxygen consumption, and attenuating mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation by inhibiting the mitochondrial calcium uniporter [16]. NecroX-5 also suppresses sodium nitroprusside-induced cardiac cell death by inhibiting c-Jun N-terminal kinases and caspase-3 activation [17]. Additionally, NecroX-7, a NecroX series derivative functionally and chemically similar to NecroX-5, reduces hepatic necrosis and inflammation in IR injury [18]. These results together suggest that NecroX-5 and other NecroX compounds may serve as drugs that can be used concurrently with reperfusion treatment to improve the overall efficiency of the treatment by reducing potentially harmful effects of reperfusion. Here, we further validate the role of NecroX-5 in preventing mitochondrial dysfunction during IR injury by preserving mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation capacity.

METHODS

Ethics statement

This investigation conformed to the rules and protocols of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996). All experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Animals at Inje University College of Medicine. Procedures were performed according to the Institutional Review Board.

Isolation of hearts

Eight-week-old male Sprague–Dawley rats (200~250 g) were deeply anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg) administered intraperitoneally [19]. Successful anesthesia was confirmed by the absence of nocifensive movement, such as the tail flick reflex [16]. Hearts were then removed from the chest cavity and quickly mounted and perfused with normal Tyrode's (NT) solution to remove all blood.

Cardiac perfusion

In the HR experimental model, hearts were sequentially perfused with NT solution for 30 minutes and ischemic solution [20] for 30 minutes, followed by perfusion with NT solution with (non-treated) or without 10 µM NecroX-5 (treated) for 60 minutes. In the control group, hearts were perfused with NT for 120 minutes.

Isolation of mitochondria

Mitochondrial pellets were collected as described previously [16,20,21]. Briefly, cardiac tissues were manually homogenized and the homogenate clarified by centrifugation at 1,000 g for 5 min at 4℃. The supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 minutes, and mitochondrial pellets were collected.

RNA extraction and Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Frozen tissues (50~100 mg) were ground into powder in liquid nitrogen and then suspended in 1 mL TRIZOL Reagent. The aqueous phase was used for RNA precipitation using an equal volume of isopropanol. The RNA pellet was washed once with 1 mL 75% ethanol, then air-dried and re-dissolved in an appropriate volume of RNase-free water. RNA was quantified using a spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). cDNA was synthesized using Taqman RT reagents (Applied Biosystems, NY, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNA synthesis thermal cycling program included the following steps: 65℃ for 5 min, 4℃ for 2 min, 37℃ for 30 min, then 95℃ for 5 min.

Relative mRNA expression levels of Ndufv2, Idh3a, Ndufa1, Ndufb8, Idh1, Hyou1, Ak2, Lum, Cabc1 and Nexn genes were performed in triplicate using SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II kit (Takara, Shiga, Japan) on CFX96. The mixture contains cDNA, SYBR green Taq polymerase mixture, and primers (Table 1). According to the manufacturer's guidelines, relative quantification was analyzed using the ΔΔCT method for. The mRNA level was normalized by control group.

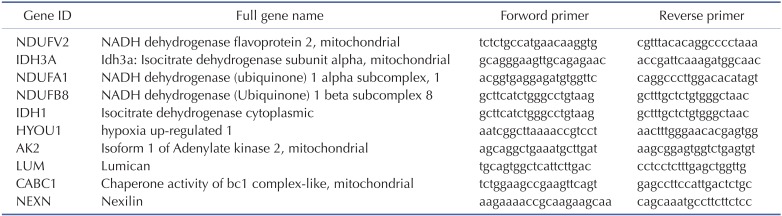

Table 1. Primer list of the examined genes.

Complex activity assay

The activity of mitochondrial complexes I, II, III, IV, and V were examined on mitochondria isolated from frozen heart tissue using a 96-well plate–based assay. The activities of complexes I, II, and IV were assessed using the corresponding Enzyme Activity Microplate Assay Kits (MitoSciences, Eugene, OR, USA) following manufacturer's instructions. A modified MitoTOX TM OXPHOS complex III activity kit (MitoSciences, Eugene, OR, USA) was used to quantify the activity of mitochondrial complex III. Data were presented as mOD/min or OD [22] and absorbance readings were obtained using a SpectraMax M2 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

To measure mitochondrial complex I activity, a total of 20 µg of mitochondrial extract from each heart was used in a NADH oxidation assay. Mitochondrial complex I was immunocaptured within microplate wells. The reduction of redox dye and concurrent NADH oxidation to NAD+ indicated complex I activity and was observed as increased absorbance at 450 nm.

To measure mitochondrial complex II activity, a total of 5 mg/ml mitochondrial extract from each heart was used in a succinate-coenzyme Q reductase assay. Mitochondrial complex II was immunocaptured in wells coated with anti-Complex II monoclonal antibody. The production of ubiquinol coupled to the reduction of the dye 2, 6-diclorophenolindophenol (DCPIP) indicated complex II activity and was observed as a decrease in absorbance at 600 nm.

To measure mitochondrial complex III activity, a total of 5 mg/ml mitochondrial extract from each heart was used, replacing the bovine heart mitochondria provided in the kit. The reduction of cytochrome c over time indicated mitochondrial complex III activity and was observed as a linear increase in absorbance at 550 nm. Rotenone and potassium cyanide were used to inhibit complex I and IV, respectively.

To measure mitochondrial complex IV activity, a total of 25 µg mitochondrial extract from each heart was immunocaptured within microplate wells. The oxidation of cytochrome c indicated mitochondrial complex IV activity and was observed as decreased absorbance at 550 nm.

Citrate synthase activity

The citrate synthase activity of mitochondrial extracts was measured using a citrate synthase assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, USA) per manufacturer's instructions. The reaction mixture contained 30 mM acetyl coenzyme A, 10 mM 5-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid, and 20~40 µg mitochondrial protein and was initiated with 10 mM oxaloacetic acid. Absorbance at 412 nm was monitored at 30-second intervals for 3 minutes at 25℃ using a SpectraMax M2 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Data are presented as units (µM/ml/min).

Protein extraction for LC-MS and peptide count protein quantification

Rat heart proteomes were analyzed by LC-MS and the non-labeled peptide count protein quantification method as described previously [23]. Briefly, dissolved heart proteins were separated on a 12% polyacrylamide gel by SDS-PAGE. Protein contained gels were sliced, dehydrated and swollen to elute the proteins for the tryptic peptide digestion. LC-MS/MS analysis was performed using a ThermoFinnigan ProteomeX workstation LTQ linear ion trap MS (Thermo Electron, San Jose, CA) equipped with NSI sources (Thermo Electron).

Protein annotation and functional network construction

Identified proteins were further categorized, annotated, and functional networks were constructed to understand the molecular functions and biological processes of each protein [24,25]. Systematic bioinformatics analysis of the HR and HR+necrox5 treated heart proteome was conducted using STRING 8.3 (Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins), Cytoscape and ClueGo.

Western blot

Protein extracts from myocardial tissues were homogenized in ice-cold Radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer containing 25 mM/L Tris · HCl (pH 7.6), 150 mM/L NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, a protease inhibitor cocktail, and a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. After brief sonication, the homogenized sample was centrifuged at 13,500 g for 30 minutes at 4℃. Protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA).

Briefly, 50~100 µg of protein from each heart was separated by 10~12% SDS-PAGE, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, UK), and blocked for 2 hours in 5% skim milk (pH 7.6) at room temperature. Membranes were then probed overnight at 4℃ with rabbit polyclonal anti-PGC1α antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) or mouse monoclonal-tubulin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, USA) diluted 1:1000. Membranes were then washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline containing Tween 20 (PBS-T; pH 7.4) and incubated for two hours at room temperature with anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) diluted 1:2000 dilution. After three more washes with PBS-T, membrane-bound proteins were visualized using a western blot detection kit (AbClon Inc., Seoul, Korea). ImageJ software, National Institutes of Health, Washington, USA was used to quantify protein bands. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as the mean±standard error of the mean (SEM). Using Origin 8.0 software (Origin Lab, Northampton, MA, USA), the differences between control and treatment groups were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the control to treatment comparison over time was tested using a two-way ANOVA. p-values ≤0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

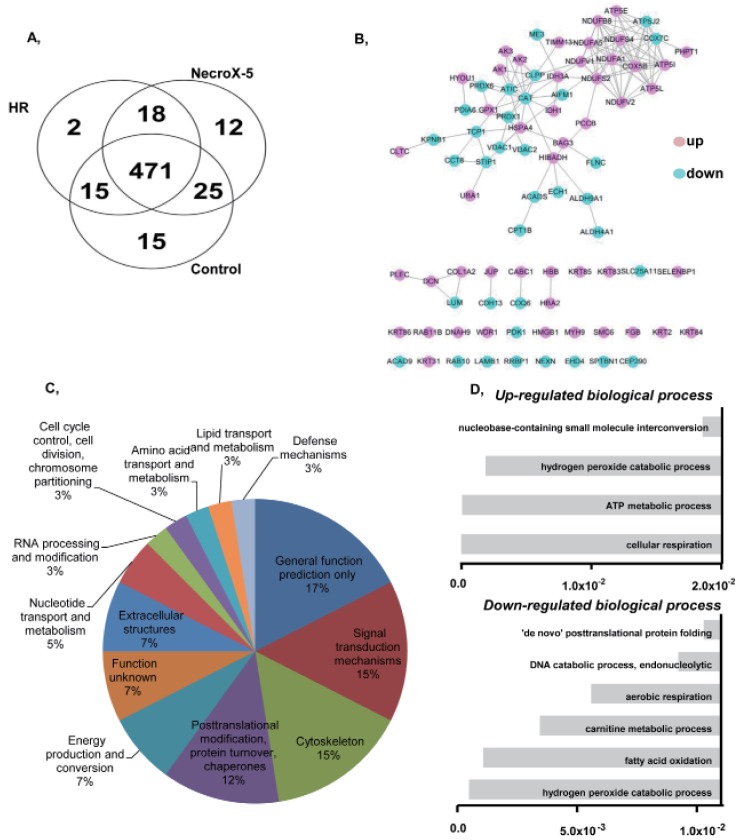

Alterations in protein levels in HR and NecroX-5 treatment groups

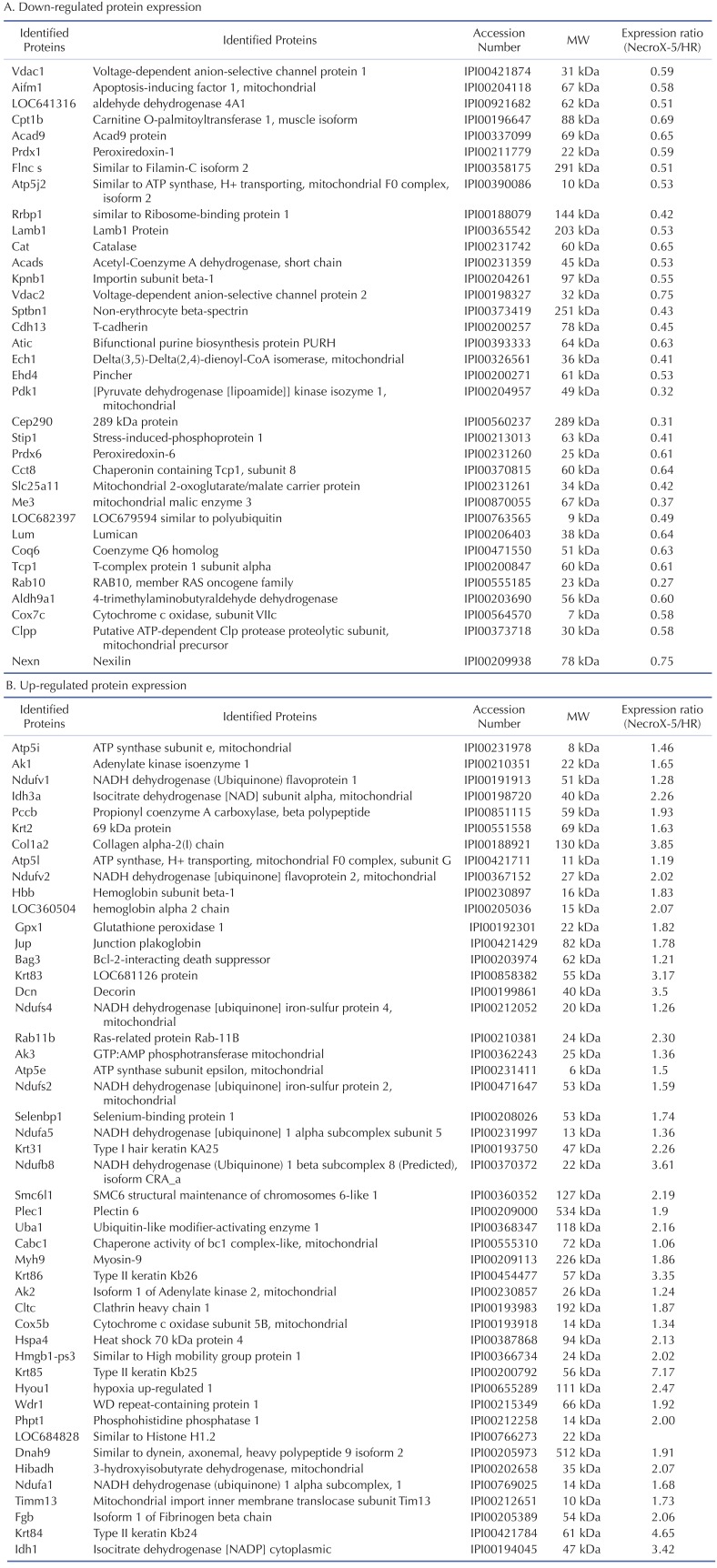

We used LC-MS to conduct protein expression profiling of Necro-X5 treated, non-treated, and control hearts. The expression levels of several identified proteins in hearts experiencing HR and NecroX-5-treated hearts are listed in Table 2. Cardiac proteins with differential expression levels among groups were classified based on their molecular functions (Fig. 1A, B) and a protein-protein interaction network was constructed. Using Clusters of Orthologous Groups of Proteins (COGs) (Fig. 1C), the proteins were divided into the following functional groups: 1) cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning; 2) lipid transport and metabolism; 3) amino acid transport and metabolism; 4) defense mechanism; 5) RNA processing and modification; 6) nucleotide transport and metabolism; 7) extracellular structures; 8) energy production and conversion; 9) posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones; 10) cytoskeleton; 11) signal transduction mechanism; and 12) general function prediction only.

Table 2. Cardiac proteins with differential expression in HR and NecroX-5 post-hypoxic treated rat heart. MW (molecular weight) was obtained from the MASCOT data base.

Fig. 1. Functional groups and protein-protein interactions of proteins identified in control, HR, and NecroX-5 treated rat hearts.

(A) A Venn diagram illustrates all possible logical relationships between proteins identified in control, HR, and NecroX-5 rat hearts. (B) A protein-protein interaction network built on identified proteins illustrates their proposed interactions in various cellular processes. (C) Functional protein groups were determined by interactive merging of initially defined groups based on the number or percentage of genes provided per term. (D) Identified proteins are presented based on their molecular functions in up- and down-regulated biological processes (Bonferonni corrected p-values).

Of these proteins, 35 were down-regulated proteins involving in hydrogen peroxide catabolic process, fatty acid oxidation, carnitine metabolic process, aerobic respiration, the DNA catabolic process, and endonucleolytic and de novo posttranslational protein folding (Table 2A and Fig. 1D). Interestingly, 48 up-regulated proteins were involved in a number of key pathways, including cellular respiration, the ATP metabolic process, the hydrogen peroxide catabolic process, and nucleobase-containing small molecule interconversion. Specifically, the expression of complex I (Ndufv2, Ndufa5, Ndufb8), complex II (Idh3a), and complex V (Atp5i, Atp5l) proteins, which are involved in the OXPHOS system and metabolic modulation, was increased in hearts tissue treated with NecroX-5 (Table 2).

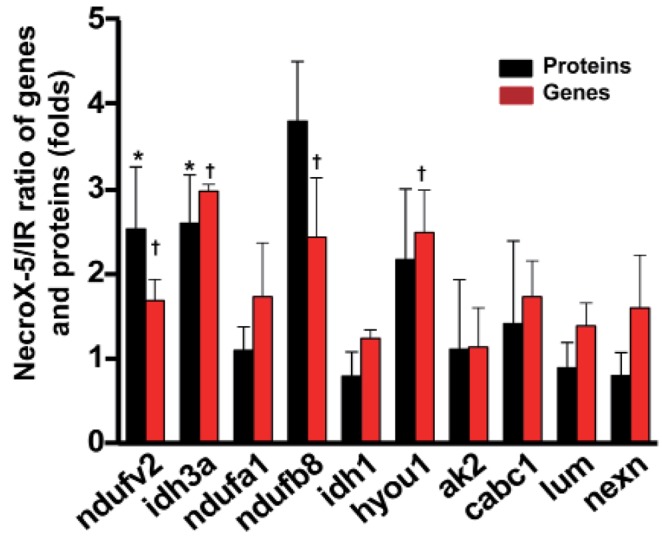

mRNA and protein expression levels and HR and NecroX-5 treated hearts reveals a NecroX-5-mediated protective effect

Ten genes coding for up-regulated proteins (such as, Ndufv2, Ndufa1, Ndufb8, Idh3a, Idh1, Hyou1, Ak2, Cabc1) and down-regulated proteins (Lum, Nexn) were randomly subjected to real-time PCR to confirm LC-MS data. As shown in Fig. 2, relative protein expression levels (NecroX-5 vs. HR hearts) corresponded quite well with relative mRNA expression levels.

Fig. 2. Quantitative real-time-PCR validation of LC-MS-mediated protein identification.

A histogram shows the ratio of summarized representative protein and mRNA expression levels between HR and NecroX-5 treated hearts. n=3~5 for each group, †p<0.05. Ndufv2: NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 2, mitochondrial; Idh3a: Isocitrate dehydrogenase [NAD] subunit alpha, mitochondrial; Ndufa1: NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 1; Ndufb8: NADH dehydrogenase (Ubiquinone) 1 beta subcomplex 8; Idh1: Isocitrate dehydrogenase [NADP] cytoplasmic; Hyou1: hypoxia upregulated 1; Ak2: Isoform 1 of Adenylate kinase 2, mitochondrial; Lum: Lumican; Cabc1: Chaperone activity of bc1 complex-like, mitochondrial; Nexn: Nexilin.

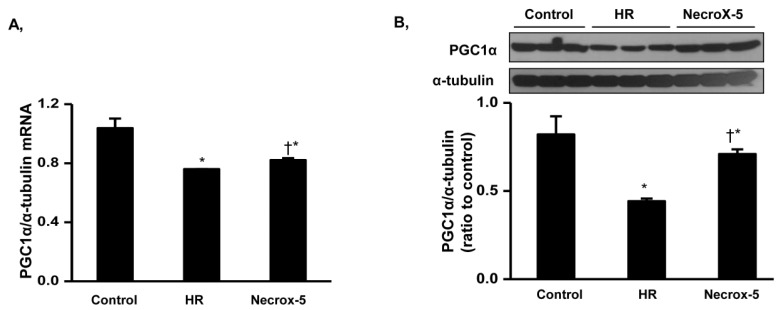

We assumed that mitochondrial changes might be associated with alterations in mitochondrial biogenesis. To evaluate our hypothesized pathway, we determined mRNA and protein expression levels of PGC1α, a mitochondrial biogenesis regulator candidate, via western blot (Fig. 3). NecroX-5 treatment of rat hears significantly attenuated HR-induced reduced PGC1α mRNA expression levels (Fig. 3A). Consistent with real-time-PCR data, PGC1α protein expression levels were markedly higher in NecroX-5 treated hearts compared to those from HR hearts (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. PGC1α mRNA and protein expression levels in control, HR, and NecroX-5 treated hearts.

Real-time PCR and Western blot were performed to assess mRNA expression (A) and protein expression (B) of PGC1α normalized to α-tubulin in rat hearts. Cardiac tissue was selected from untreated HR hearts and HR hearts treated with 10 µM NecroX-5. n=3~6 for each group; *p<0.05 vs. control, †p<0.05 vs. HR.

Mitochondrial parameters

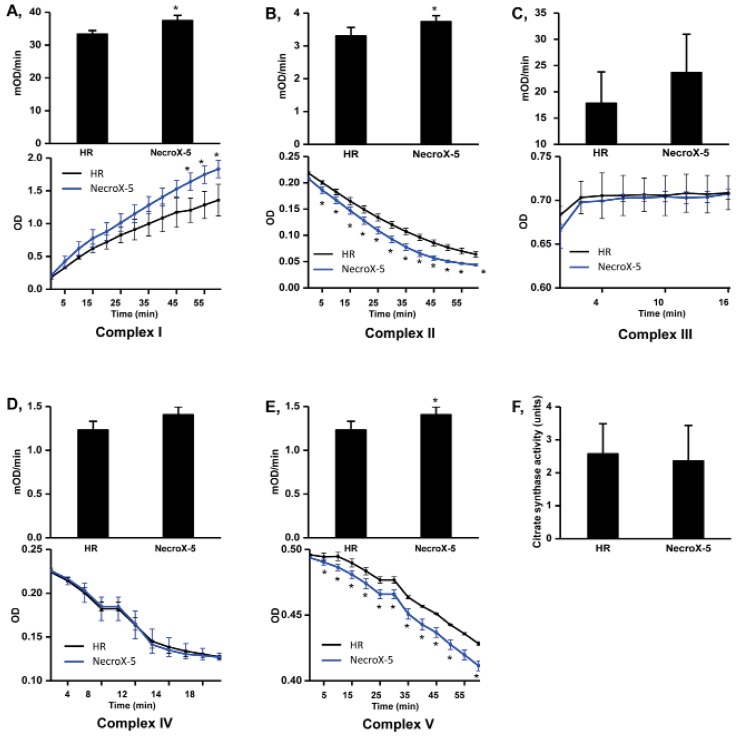

We then further examined the protective effects of NecroX-5 on HR injury in the context of mitochondrial energy metabolism. Mitochondrial complex activities were tested after 60 minutes of reperfusion. The activities of complex I, II, and V (mOD/min) were significantly higher in NecroX-5 treated hearts (37.44±1.59, 3.74±0.18, and 1.41±0.09, respectively; p<0.05) compared to HR (non-treated) hearts (33.33±1.09, 3.30±0.26, and 1.23±0.10, respectively). However, there was no significant difference in the complex III activity (17.82±5.98 and 23.67±2.29), complex IV activity (7.49±1.69 and 7.61±0.90, respectively), or citrate synthase activity (2.58±0.91 and 2.36±1.08 units) between HR group and NecroX-5 group (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Mitochondrial complex and citrate synthase activities in HR and NecroX-5 treated hearts.

Graphs illustrated the activity of mitochondrial complexes I~V (mOD/min) with the relative Vmax curves of complex I~V activity (OD) (A~E, upper panels) and mitochondrial citrate synthase activity (F) in untreated HR hearts and NecroX-5 treated HR hearts. n=4~5 for each groups; *p<0.05.

DISCUSSION

Here, we show that NecroX-5 significantly improves mitochondrial function in rat hearts experiencing HR injury by preserving mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation capacity and PGC1α expression.

NecroX-5 protects mitochondrial function against HR

Previous studies have clearly indicated that NecroX-5 suppresses OXPHOS system dysfunction and the tricarboxylic acid cycle in rat hearts undergoing HR [16]. Improved oxygen consumption indexes and maintenance of the Δψm further support the protective effects of NecroX-5 on mitochondrial metabolism in hypoxic cardiac tissue [16]. The assessment of mitochondrial complex activity is a common approach for characterizing mitochondrial bioenergetics dysfunction, with higher expression levels of mitochondrial complex proteins corresponding to increased mitochondrial complex activity. Given this, mitochondrial complex activities and protein expression levels which are involved in the OXPHOS system and metabolic modulation were increased in NecroX-5 received hearts compared to those in HR hearts (Fig. 4, Table 2).

Any decrease in OXPHOS protein levels could adversely affect the ΔΨm, further contributing to mitochondrial malfunction. Mitochondrial complex I is well-known to play an important role in maintaining the ΔΨm [26], and mitochondrial complex I deficiency is responsible for 40% of OXPHOS disorders [27]. As a core subunit of this complex, Ndufv2 is a key regulator of complex I activity; depletion of this protein causes a decrease in complex I activity. Mutation of the Ndufv2 gene causes cardiomyopathy [28]. In addition to preserving mitochondrial complex I and II protein levels and activities, NecroX-5 also significantly suppressed the HR-induced defects in mitochondrial complex V (the ATP synthase complex). These results together with our earlier study [16] suggest that mitochondrial ATP generating capacity is improved in HR hearts upon NecroX-5 treatment. Additionally, a high rate of respiration control in NecroX-5 treated hearts may result from a properly functioning OXPHOS pathway, suggesting that the mitochondria have a high capacity for substrate oxidation and ATP turnover [6]. These observations suggest that treated of hearts undergoing HR with NecroX-5 prevents the loss of crucial OXPHOS subunit proteins and, therefore, suppresses mitochondrial malfunction. As described in Table 2, the expression levels of other proteins involved in energetic metabolism, such as Idh1 and Idh3a (glycolysis) were higher in NecroX-5-treated hearts [21]. All of these processes would provide sufficient energy for ATP metabolism (see up-regulated biological process, Fig. 1D and Table 2B), leading to improved cardiac performance [16].

One research group previously demonstrated that malfunction of mitochondrial bioenergetics is coupled with complex II deficiency-mediated calcium handling [29]. In this, mitochondrial complex II protein expression activity were higher in NecroX-5 hearts, further supporting the previously described inhibitory role of NecroX-5 on the mitochondrial calcium uniporter [16]. Additionally, we previously described lower reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in NecroX-5 treated hearts compared to HR hearts [16]. Therefore, the improvement of complex II activity upon NecroX-5 treatment may contribute to improved modulation of ROS production in mitochondrial complexes I and III during HR injury [30].

Decreased PGC1α levels have been observed in myocardial infarcted rat hearts; however, treatment of metformin [14] or losartan [13] can improve left ventricular function with significantly higher PGC1α expression levels. Levels also increased within 3 hours after short-term deprivation of nutrients and oxygen conditions such as in IR and HR [31,32,33]. Although PGC1α expression increased after a longer period of oxygen deprivation, acute HR or IR is associated with PGC1α levels [32,33]. It has been shown that transcriptional suppression of autophagylysosome proteins and reduced activation of transcription factor EB (TFEB) are essential for sustaining lysosome function and enhancing cell survival under starvation conditions [34]. Upregulation of beclin-1 upon of HR-associated ROS elevation suppressed the TEEB-PGC1α axis, triggering IR-induced cardiomyocyte death [33]. We also tested whether changes in mitochondrial function were associated with alterations in mitochondrial biogenesis by evaluating the expression of PGC1α, a mitochondrial biogenesis regulator candidate. Consistent with previous reports [13,14,32,33], PGC1α mRNA and protein levels were significantly higher in NecroX-5 treated hearts compared to untreated HR hearts. Additionally, ROS and Ca2+ can increase PGC1α degradation [35]; therefore, increased PGC1α levels in NecroX-5 group may be a result of lower ROS and calcium levels, as shown in our previous study [16]. We suggest that NecroX-5 treatment induces mitochondrial biogenesis regulatory programs to augment cardiac tolerance to hypoxic injury by preserving the capacity of the OXPHOS pathway to maintain mitochondrial energetics and modulate ROS in response to metabolic stress [10,16].

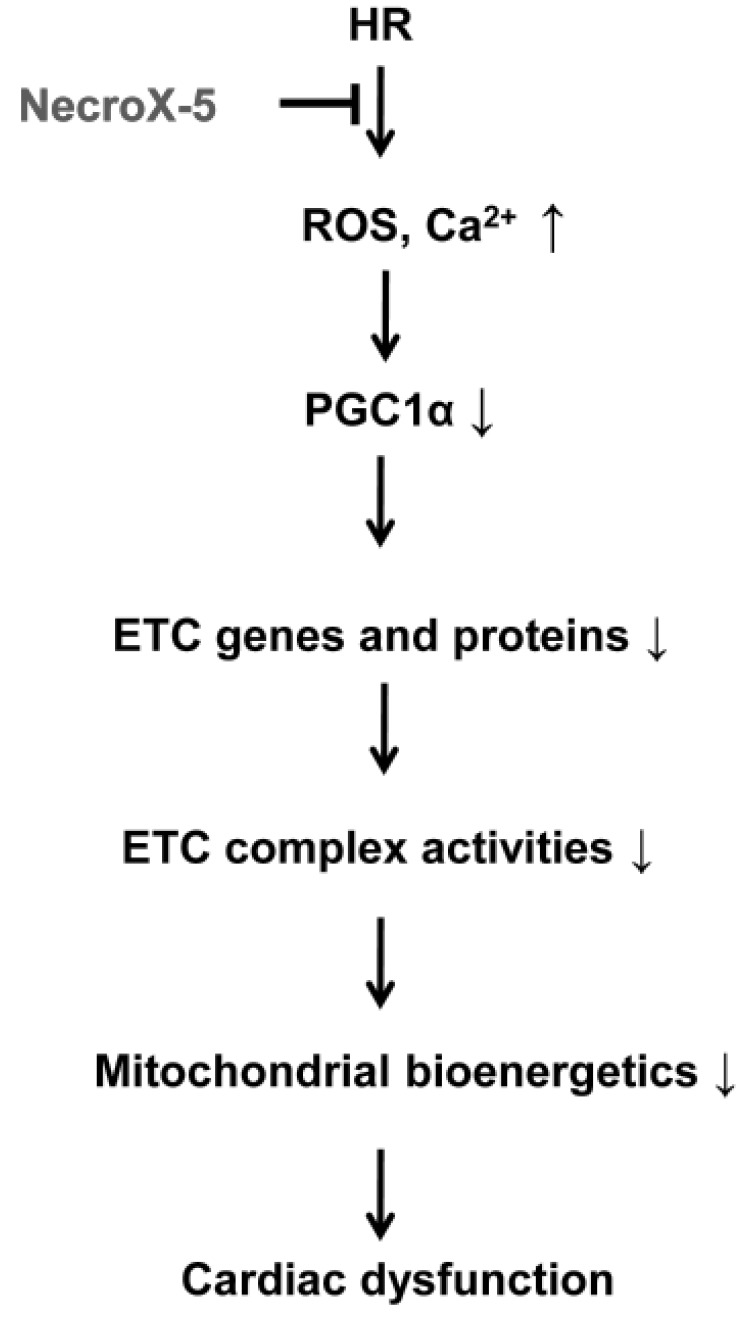

The beneficial effects of NecroX-5 on mitochondrial function may be achieved by several mechanisms. First, NecroX-5 could prevent the reduction of OXPHOS proteins and increase OXPHOS maximal capacity in HR hearts. Second, preserved OXPHOS capacity by NecroX-5 can produce ATP more effectively than is seen in HR hearts during the early reoxygenation period. Additionally, increased biogenesis is likely to be associated with improved mitochondrial bioenergetics (Fig. 4 and 5). Therefore, augmented bioenergetics upon NecroX-5 treatment may aid in mitochondrial resistance to ischemic injury [10]. Combined with our previous report [16], the proposed function of NecroX-5 described here (Fig. 5) suggests for the first time that the protection of OXPHOS capacity and preservation of PGC1α expression may account for the protective effects of NecroX-5 against HR-induced injury. However, our present data were based on in vitro and ex vivo models. Therefore, in vivo testing is necessary for a more thorough understanding of the role of NecroX-5 during HR-induced injury. Additionally, based on proteomics data (unpublished data); further studies should be done to address more comprehensive roles and mechanical actions of NecroX-5 in the context of HR-induced injury.

Fig. 5. Proposed function of NecroX-5 during HR injury.

ETC, electron transport chain; HR, hypoxia/reoxygenation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF). Funds were granted by the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning of Korea (2012R1A2A1A03007595) and by the Ministry of Education of Korea (2010-0020224).

Footnotes

Author contributions: V.T.T. and H.K.K designed experiments and performed animal experiments. L.T.L. performed langendorff heart experiments. B.N., I-S. S. and J.M. performed western blot analysis. T.T.T. and N.Q.H. contributed to proteome analysis. S.H.K. and N.K. contributed to chemical preparation. K.S.K. and B.D.R contributed to mitochondria complex assays. J.H. supervised and coordinated the study. V.T.T. and H.K.K. wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Carden DL, Granger DN. Pathophysiology of ischaemia-reperfusion injury. J Pathol. 2000;190:255–266. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200002)190:3<255::AID-PATH526>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halestrap AP. A pore way to die: the role of mitochondria in reperfusion injury and cardioprotection. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38:841–860. doi: 10.1042/BST0380841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleinbongard P, Schulz R, Heusch G. TNFα in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion, remodeling and heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2011;16:49–69. doi: 10.1007/s10741-010-9180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ribichini F, Wijns W. Acute myocardial infarction: reperfusion treatment. Heart. 2002;88:298–305. doi: 10.1136/heart.88.3.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xia A, Xue Z, Wang W, Zhang T, Wei T, Sha X, Ding Y, Zhou W. Naloxone postconditioning alleviates rat myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury by inhibiting JNK activity. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014;18:67–72. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2014.18.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brand MD, Nicholls DG. Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. Biochem J. 2011;435:297–312. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy E, Steenbergen C. Mechanisms underlying acute protection from cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:581–609. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00024.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piot C, Croisille P, Staat P, Thibault H, Rioufol G, Mewton N, Elbelghiti R, Cung TT, Bonnefoy E, Angoulvant D, Macia C, Raczka F, Sportouch C, Gahide G, Finet G, André-Fouët X, Revel D, Kirkorian G, Monassier JP, Derumeaux G, Ovize M. Effect of cyclosporine on reperfusion injury in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:473–481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heller A, Brockhoff G, Goepferich A. Targeting drugs to mitochondria. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2012;82:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLeod CJ, Pagel I, Sack MN. The mitochondrial biogenesis regulatory program in cardiac adaptation to ischemia--a putative target for therapeutic intervention. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim HK, Thu VT, Heo HJ, Kim N, Han J. Cardiac proteomic responses to ischemia-reperfusion injury and ischemic preconditioning. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2011;8:241–261. doi: 10.1586/epr.11.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ventura-Clapier R, Garnier A, Veksler V. Transcriptional control of mitochondrial biogenesis: the central role of PGC-1alpha. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:208–217. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun CK, Chang LT, Sheu JJ, Wang CY, Youssef AA, Wu CJ, Chua S, Yip HK. Losartan preserves integrity of cardiac gap junctions and PGC-1 alpha gene expression and prevents cellular apoptosis in remote area of left ventricular myocardium following acute myocardial infarction. Int Heart J. 2007;48:533–546. doi: 10.1536/ihj.48.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gundewar S, Calvert JW, Jha S, Toedt-Pingel I, Ji SY, Nunez D, Ramachandran A, Anaya-Cisneros M, Tian R, Lefer DJ. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase by metformin improves left ventricular function and survival in heart failure. Circ Res. 2009;104:403–411. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.190918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim HJ, Koo SY, Ahn BH, Park O, Park DH, Seo DO, Won JH, Yim HJ, Kwak HS, Park HS, Chung CW, Oh YL, Kim SH. NecroX as a novel class of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and ONOO– scavenger. Arch Pharm Res. 2010;33:1813–1823. doi: 10.1007/s12272-010-1114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thu VT, Kim HK, Long le T, Lee SR, Hanh TM, Ko TH, Heo HJ, Kim N, Kim SH, Ko KS, Rhee BD, Han J. NecroX-5 prevents hypoxia/reoxygenation injury by inhibiting the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;94:342–350. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SR, Lee SJ, Kim SH, Ko KS, Rhee BD, Xu Z, Kim N, Han J. NecroX-5 suppresses sodium nitroprusside-induced cardiac cell death through inhibition of JNK and caspase-3 activation. Cell Biol Int. 2014;38:702–707. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi JM, Park KM, Kim SH, Hwang DW, Chon SH, Lee JH, Lee SY, Lee YJ. Effect of necrosis modulator necrox-7 on hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury in beagle dogs. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:3414–3421. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takaseya T, Ishimatsu M, Tayama E, Nishi A, Akasu T, Aoyagi S. Mechanical unloading improves intracellular Ca2+ regulation in rats with doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:2239–2246. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim N, Lee Y, Kim H, Joo H, Youm JB, Park WS, Warda M, Cuong DV, Han J. Potential biomarkers for ischemic heart damage identified in mitochondrial proteins by comparative proteomics. Proteomics. 2006;6:1237–1249. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thu VT, Kim HK, Ha SH, Yoo JY, Park WS, Kim N, Oh GT, Han J. Glutathione peroxidase 1 protects mitochondria against hypoxia/reoxygenation damage in mouse hearts. Pflugers Arch. 2010;460:55–68. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0811-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HK, Song IS, Lee SY, Jeong SH, Lee SR, Heo HJ, Thu VT, Kim N, Ko KS, Rhee BD, Jeong DH, Kim YN, Han J. B7-H4 downregulation induces mitochondrial dysfunction and enhances doxorubicin sensitivity via the cAMP/CREB/PGC1-α signaling pathway in HeLa cells. Pflugers Arch. 2014;466:2323–2338. doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1493-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim HK, Kim YK, Song IS, Lee SR, Jeong SH, Kim MH, Seo DY, Kim N, Rhee BD, Ko KS, Tark KC, Park CG, Cho JY, Han J. Human giant congenital melanocytic nevus exhibits potential proteomic alterations leading to melanotumorigenesis. Proteome Sci. 2012;10:50. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-10-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Hackl H, Charoentong P, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Fridman WH, Pagès F, Trajanoski Z, Galon J. Clue-GO: a Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1091–1093. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen LJ, Kuhn M, Stark M, Chaffron S, Creevey C, Muller J, Doerks T, Julien P, Roth A, Simonovic M, Bork P, von Mering C. STRING 8--a global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D412–D416. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Distelmaier F, Koopman WJ, van den Heuvel LP, Rodenburg RJ, Mayatepek E, Willems PH, Smeitink JA. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency: from organelle dysfunction to clinical disease. Brain. 2009;132:833–842. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morán M, Rivera H, Sánchez-Aragó M, Blázquez A, Merinero B, Ugalde C, Arenas J, Cuezva JM, Martín MA. Mitochondrial bioenergetics and dynamics interplay in complex I-deficient fibroblasts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:443–453. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bénit P, Beugnot R, Chretien D, Giurgea I, De Lonlay-Debeney P, Issartel JP, Corral-Debrinski M, Kerscher S, Rustin P, Rötig A, Munnich A. Mutant NDUFV2 subunit of mitochondrial complex I causes early onset hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and encephalopathy. Hum Mutat. 2003;21:582–586. doi: 10.1002/humu.10225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mbaya E, Oulès B, Caspersen C, Tacine R, Massinet H, Pennuto M, Chrétien D, Munnich A, Rötig A, Rizzuto R, Rutter GA, Paterlini-Bréchot P, Chami M. Calcium signalling-dependent mitochondrial dysfunction and bioenergetics regulation in respiratory chain Complex II deficiency. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:1855–1866. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gill RS, Lee TF, Manouchehri N, Liu JQ, Lopaschuk G, Bigam DL, Cheung PY. Postresuscitation cyclosporine treatment attenuates myocardial and cardiac mitochondrial injury in newborn piglets with asphyxia-reoxygenation. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1069–1074. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182746704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arany Z, Foo SY, Ma Y, Ruas JL, Bommi-Reddy A, Girnun G, Cooper M, Laznik D, Chinsomboon J, Rangwala SM, Baek KH, Rosenzweig A, Spiegelman BM. HIF-independent regulation of VEGF and angiogenesis by the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha. Nature. 2008;451:1008–1012. doi: 10.1038/nature06613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma X, Liu H, Foyil SR, Godar RJ, Weinheimer CJ, Hill JA, Diwan A. Impaired autophagosome clearance contributes to cardiomyocyte death in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2012;125:3170–3181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.041814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma X, Liu H, Murphy JT, Foyil SR, Godar RJ, Abuirqeba H, Weinheimer CJ, Barger PM, Diwan A. Regulation of the transcription factor EB-PGC1α axis by beclin-1 controls mitochondrial quality and cardiomyocyte death under stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35:956–976. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01091-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Settembre C, De Cegli R, Mansueto G, Saha PK, Vetrini F, Visvikis O, Huynh T, Carissimo A, Palmer D, Klisch TJ, Wollenberg AC, Di Bernardo D, Chan L, Irazoqui JE, Ballabio A. TFEB controls cellular lipid metabolism through a starvation-induced autoregulatory loop. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:647–658. doi: 10.1038/ncb2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rasbach KA, Green PT, Schnellmann RG. Oxidants and Ca2+ induce PGC-1alpha degradation through calpain. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;478:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]