Abstract

The opposing catalytic activities of topoisomerase I (TopoI/relaxase) and DNA gyrase (supercoiling enzyme) ensure homeostatic maintenance of bacterial chromosome supercoiling. Earlier studies in Escherichia coli suggested that the alteration in DNA supercoiling affects the DNA gyrase and TopoI expression. Although, the role of DNA elements around the promoters were proposed in regulation of gyrase, the molecular mechanism of supercoiling mediated control of TopoI expression is not yet understood. Here, we describe the regulation of TopoI expression from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium smegmatis by a mechanism termed Supercoiling Sensitive Transcription (SST). In both the organisms, topoI promoter(s) exhibited reduced activity in response to chromosome relaxation suggesting that SST is intrinsic to topoI promoter(s). We elucidate the role of promoter architecture and high transcriptional activity of upstream genes in topoI regulation. Analysis of the promoter(s) revealed the presence of sub-optimal spacing between the −35 and −10 elements, rendering them supercoiling sensitive. Accordingly, upon chromosome relaxation, RNA polymerase occupancy was decreased on the topoI promoter region implicating the role of DNA topology in SST of topoI. We propose that negative supercoiling induced DNA twisting/writhing align the −35 and −10 elements to facilitate the optimal transcription of topoI.

INTRODUCTION

Negative supercoiling of the bacterial chromosome is essential for the optimal functioning of the DNA transaction processes (1,2). Negative super-helical density, in general, facilitates the promoter melting and promotes the transcription of genes (3). Alteration in the steady state level of chromosome supercoiling influences the bacterial gene expression (4) and hence chromosome supercoiling has to be regulated for the optimal growth and physiology of the cell. DNA topoisomerases are the major regulators of chromosome supercoiling in bacteria (2). In E. coli, DNA gyrase introduces the negative supercoiling while topoisomerase I (TopoI) and topoisomerase IV (TopoIV) relax the excess supercoiling generated by DNA gyrase and active transcription/replication machinery (5–8). For the regulation of chromosome supercoiling, there must be a mechanism to sense, interpret and respond to alterations in super-helical density to bring it back to the steady-state level. Indeed, a mechanism has evolved for the regulation of topoisomerases which operates by sensing the alterations in the chromosome supercoiling (9–12). The response is generated in the form of alteration in the expression of topoisomerases. The regulation of topoisomerase expression has been studied in E. coli (12–14). Expression of the supercoiling enzyme DNA gyrase was shown to increase in response to relaxation (14). This phenomenon of autoregulation of DNA gyrase is termed as Relaxation Stimulated Transcription (RST) (10). On the other hand, expression of DNA TopoI—the primary relaxase in E. coli was found to increase marginally when chromosome was negatively supercoiled (9) and the expression was significantly down-regulated in response to chromosome relaxation (12). Such autoregulation of the expression of topoisomerases facilitates the maintenance of topological homeostasis in the cell.

The underlying mechanism for gyrase regulation has been elucidated in E. coli and mycobacteria. In E. coli, the regulatory mechanism of gyrA and gyrB expression is an attribute of the intrinsic property of DNA elements in and around the promoter, particularly the −10 region (10,15–17) while in M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis the role of the distal promoter elements and overlapping promoter has been implicated in the regulation of the gyrase operon, respectively (18,19). Studies in E. coli identified the supercoiling responsive promoters of topoI (11,12). The promoter(s) activity was found to alter with the change in environmental condition and the role of sigma factors in the regulation of topoI expression was deciphered (20,21). However, the molecular mechanism or the involvement of DNA elements in conferring the supercoiling sensitivity to topoI promoter(s) remains to be elucidated.

Several members of the genus Mycobacterium encounter unfavorable environments and adapt to hostile conditions (22,23). DNA supercoiling and topoisomerases may assist in the re-configuration of gene expression required for such adaptations (24). The mycobacterial chromosome encodes a single Type IA enzyme which has been shown to be essential for the cell growth (25). The absence of additional relaxases (unlike in E. coli) in mycobacteria suggests the additional responsibility for TopoI in regulating the relaxation of the chromosome. In order to sustain the optimal chromosome supercoiling, the topoisomerase activity in the mycobacterial chromosome needs to be appropriately balanced. We describe the regulation of topoI in non-pathogenic M. smegmatis and the pathogenic M. tuberculosis. Mapping of the transcripts of topoI in both the mycobacterial species showed the presence of two promoters. Both the promoters were found to be sensitive to the change in chromosome supercoiling and their intrinsic properties contribute in the Supercoiling Sensitive Transcription (SST) of topoI in both the organisms. In addition high transcription of an upstream gene affected the topology of topoI regulatory region, influencing its activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth media and transformation conditions

The following bacterial strains were used: E. coli DH10B (laboratory stock), M. smegmatis mc2 155 (laboratory stock), M. tuberculosis H37Ra. E. coli strains were grown at 37°C in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar plates. Mycobacterial strains were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco) or 7H10 agar plates (Difco), supplemented with 0.2% glycerol and 0.05% Tween-80 at 37°C. For the M. tuberculosis, the medium was supplemented with 10% ADC (Albumin, Dextrose and NaCl). Antibiotics were added to the media at the following concentrations: 25 μg/ml Kanamycin (Sigma Aldrich, CA, USA), 25 ng/ml Tetracycline (Sigma Aldrich, CA, USA).

Cloning of topoI gene and its promoter

TopoI overexpressing constructs were generated in pMIND vector system (26). The M. smegmatis topoI gene was amplified from pPVN123 (27). The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products were digested with NdeI and EcoRV and cloned into pMIND vector linearized with NdeI and EcoRV (26). Clones were confirmed by double digestion with NdeI and BamHI, and the expression of TopoI in M. smegmatis cells was monitored by immunoblotting. The 1.5 kb upstream promoter regions of M. smegmatis topoI and M. tuberculosis topoI were cloned upstream to the β-galactosidase gene in the pSD5B promoterless vector (28) at the XbaI site. This construct (2 μg plasmid) was electroporated into M. smegmatis. Recombinant colonies were selected on 7H10 agar plates containing Kanamycin (25 μg/ml). For the insertion of nucleotides in the spacer region of PMstopo2, megaprimer inverse PCR mutagenesis strategy was employed (29). Briefly, the 530 bp upstream region of topoI gene cloned into the pSD5B was used as a template and forward primers containing 3 or 4 additional nucleotides were utilized to introduce insertion mutations in the spacer of major promoter (based on expression) Mstopo2.

Immunoblot analysis

25 μg of total cell lysates were separated on 8% sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to PVDF membranes. Prior to probing with antibody, the equal loading and transfer of lysates to membrane was ensured by Ponceau S staining. Membranes were incubated in PBS blocking buffer (10 mM Na- phosphate, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) with 2% (w/v) BSA for 2 h prior to incubation with primary antibodies diluted (1:20 000) in PBS with 2% BSA for 2 h. Membranes were washed in PBST (.05% Tween 20) three times, and then incubated with secondary antibodies for 2 h followed by washing three times with PBST. Protein bands were visualized using chemiluminescent substrates (Millipore).

RNA extraction and qPCR

RNA was extracted from M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis exponentially grown cells using a Qiagen RNeasy kit following the manufacturer's protocol. From the total RNA, cDNAs were synthesized using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). cDNA generated with random primers was used for quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), with SYBR green as the indicator dye. The expression of the genes was quantified after normalization of RNA levels to the expression of the sigA transcript. The qPCR cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 57°C for 30 s and 72°C for 20 s.

Primer extension

For primer extension, 5 μg of total RNA isolated from log phase cultures of M. smegmatis or M. tuberculosis was heated to 65°C, rapidly chilled, followed by the addition of primers (which anneals to the 5′end of topoI coding region) and incubation at 55°C, again chilled and extension mix (containing 10 mM dNTP mix and 200 units RevertAid Premium Reverse Transcriptase) was added followed by incubation at 50°C for 1 h. The products were separated in a 6% sequencing gel. The size of the products was deduced using a sequencing reaction. For sequencing, the pUC-T7A1 plasmid and pUC forward primer were used. Gels were scanned in a Typhoon 9500 (GE) phosphorimager.

β-galactosidase reporter assay

Promoter strength was measured by β-galactosidase reporter assay and the activity represented in Miller units [(Miller units = 1000 × A420/ (time (min) x volume of culture (ml) x optical density at 600 nm)](30). M. smegmatis harboring vector pSD5B was used as the negative control. To determine the in vivo promoter strength in different growth phases, promoter fusion constructs were introduced into M. smegmatis and the resulting strains were grown for 4, 8, 12, 16, 26, 32, 40 h and promoter activity was determined.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and RT PCR

ChIP with exponentially grown M. smegmatis cultures was carried out as described previously (31). Briefly, formaldehyde cross-linked cells were lysed by sonication (by Bioruptor; Diagenode) to shear the DNA. The fragmented DNA was immunoprecipitated by using the anti-RpoB or anti-GyrA antibody and purified. The resulting ChIP-DNA was subjected to qRT PCR analysis to determine the enrichment of the topoI promoter region (or other targets) in immunoprecipitated (IP) sample over the mock-IP (without antibody) sample.

RESULTS

Supercoiling sensitive expression of TopoI

In order to decipher the effect of different cues on the expression of TopoI, M. smegmatis cells were exposed to different stress conditions and TopoI expression was monitored. Out of the several conditions tested, the DNA gyrase inhibitor—novobiocin, drastically affected the expression of TopoI (Supplementary Figure S1). The inhibition of DNA gyrase induces the relaxation of the chromosome (32,33) and thus the observed reduction in the TopoI level in the presence of novobiocin suggested the supercoiling sensitive expression of TopoI. The analysis of mycobacterial cell lysates prepared from the novobiocin treated cells showed an enhanced expression of DNA gyrase indicating the operation of relaxation stimulated transcription (RST) of DNA gyrase in mycobacteria (Figure 1A and Supplementary Figure S2). Further, with an increase in the novobiocin concentration or the time of exposure, the level of TopoI was found to decrease gradually (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure S2). The transcript analysis of topoI suggested the decrease in the transcript abundance of the gene (Figure 1C) suggesting that the topoI gene exhibits SST. The validation of the SST of topoI was carried out by the relaxation of the chromosome of M. smegmatis by overexpressing the TopoI under tetracycline inducible system and scoring the transcription of genomic copy of topoI. The unique 5′UTR of the genomic copy of topoI forms the basis of discriminatory qRT PCR allowing the measurement of alteration in the transcript abundance of the genomic copy of topoI even in the presence of plasmid copy of topoI (Figure 2A). To ensure that the overexpression of TopoI upon induction with tetracycline led to the chromosome relaxation plasmid DNA were isolated and their topology was analyzed by chloroquine-agarose gel electrophoresis. Indeed, the plasmid isolated from the cells overexpressing TopoI exhibits accumulation of the relaxed topoisomers (Supplementary Figure S3). Moreover, the overexpression of TopoI led to the increased expression of DNA gyrase which is an indication of RST—a characteristic of chromosome relaxation (10) (Figure 2B). The discriminatory RT PCR analysis revealed the concomitant decrease in the abundance of transcript of the genomic copy of topoI (Figure 2C). To confirm that the reduction in the genomic copy of topoI was an attribute of the chromosome relaxation brought about by TopoI and not the result of overproduction of TopoI, we overexpressed TopoI mutant which is relaxation deficient (TopoIΔ23) (34). The overexpression of the mutant did not affect the expression of chromosomal topoI suggesting that DNA relaxation induced by TopoI down-regulates its own expression (Figure 2C). Overall, the data confirm the supercoiling sensitive autoregulation of topoI in mycobacteria.

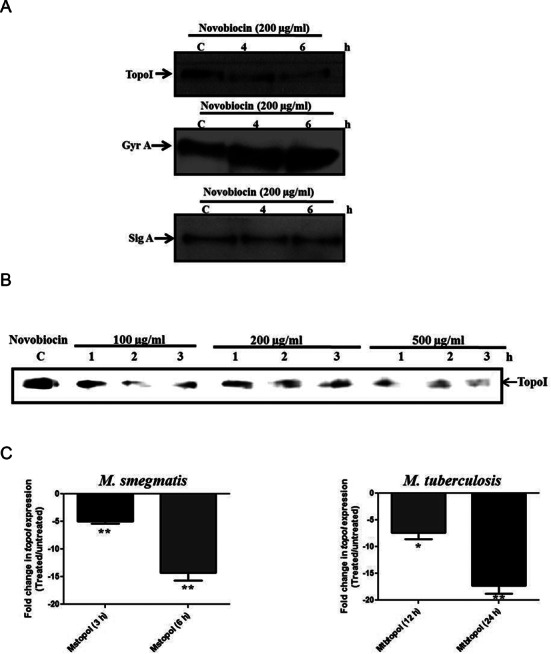

Figure 1.

TopoI expression is sensitive to gyrase inhibition. M. smegmatis cells were grown to exponential phase and treated with the different concentrations of novobiocin to induce chromosome relaxation. The cells were lysed and subjected to immunoblot analysis using specific antibodies against the proteins of interest (as indicated in the panel). (A) M. smegmatis cells treated with 200 μg/ml novobiocin for 4–6 h and the expression of TopoI, GyrA and SigA was monitored. (B) Dose dependent repression of TopoI expression by novobiocin. The M. smegmatis cells were exposed to various concentrations of novobiocin for different time and TopoI expression was monitored. (C) Transcript analysis of TopoI expression. The exponential phase cells of M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis treated with the novobiocin (100 μg/ml) for 3 h–6 h and 12–24 h, respectively. Total RNA was isolated from treated and untreated cells and cDNA was prepared using random hexamer primers. Abundance of topoI transcript was measured by qRT PCR analysis using gene specific primers. Fold change in topoI expression compared to the untreated culture. sigA was used as a reference gene for the expression analysis. The error bars represent the SD (standard deviation) obtained from three independent experiments. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Reduced expression of TopoI upon chromosome relaxation. The chromosome relaxation was carried out by ectopic overexpression of M. smegmatis TopoI using tetracycline inducible system. The exponential phase M. smegmatis cells were treated with the tetracycline (25 ng/ml) for 6 h and the expression of TopoI and DNA gyrase was monitored both at protein as well as RNA level. (A) Schematic for the discriminatory qRT PCR. The 5′ UTR of the ectopically expressed topoI (etopoI) and genomic copy of topoI (gtopoI) were different. The primers specific for gtopoI were used to determine the alteration in the expression of gtopoI upon TopoI overexpression (to cause chromosome relaxation). (B) Immunoblot analysis of TopoI and gyrase expression upon induction with the tetracycline. The increased overexpression of GyrA upon TopoI overexpression indicates the chromosome relaxation (RST). (C) Measurement of the genomic topoI transcript abundance in the cells upon overexpression of TopoI by discriminatory qRT PCR analysis. The fold change is expression represents the expression of topoI transcripts upon tetracycline induction normalized with the uninduced RNA samples. topoI (ORF) indicates the expression of total topoI transcripts; gtopoI and etopoI represents the expression of genomic copy and plasmid copy of topoI transcripts, respectively. The error bars represents the SD obtained from three independent experiments. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.001, ns: not significant (P > 0.1).

Evaluation of mycobacterial topoI promoter activity

To assess the activity of mycobacterial topoI promoter(s), the 1.5 kb region encompassing the two upstream genes (MSMEG_6158/Rv3647c and MSMEG_6159/Rv3648c) and putative topoI promoters (Supplementary Figure S4) were cloned in the promoter less plasmid pSD5B (28), harboring the reporter gene β-galactosidase for the promoter activity analysis. The constructs were introduced into both E. coli and M. smegmatis cells to monitor the expression of reporter gene cloned under the topoI promoter(s). The expression of β-galactosidase was not seen in the E. coli while the promoter activity was observed in M. smegmatis (blue colonies, Supplementary Figures S5A and S6A) suggesting that the expression of topoI promoter(s) was restricted to mycobacteria. The inability of topoI promoter to express in E. coli could be associated with the differences in the promoter recognition motifs/elements between the two organisms. The activity of both the M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis topoI promoters was found to be growth-phase dependent (Supplementary Figures S5B and S6B). In early exponential phase, the expression was found to be highest which decreased with the rise in the culture's optical density.

Since, the topoI exhibits supercoiling sensitive expression, we monitored the influence of the environmental conditions which are known to alter the DNA topology. An increase in extracellular osmolarity was shown to elevate the in vivo DNA supercoiling in E. coli and Salmonella (35,36). Similarly, the high salt concentration or hypertonic sucrose solution led to an enhancement in the mycobacterial topoI promoter activity indicating the supercoiling induced activity of topoI promoter(s) (Supplementary Figure S7A and S7B). The change in the growth temperature is also known to affect the plasmid linking number/DNA topology (37) although the direction of the alteration varies across the bacterial species (37–39). The increase in the relaxed topoisomers of the plasmid isolated from the M. smegmatis growing at 42°C suggested the relaxation of the chromosome (Supplementary Figure S7C). These alterations in DNA topology are similar to what is seen in Shigella, Salmonella and halophilic archaeon Haloferax volcanii (38,39) but opposite to that of E. coli (37). The temperature dependent decrease in topoI promoter activity seen for mycobacterial promoter is the consequence of DNA relaxation (Supplementary Figure S6C). Moreover, the activity of the topoI promoters in the plasmid context was also found to be reduced in response to the DNA relaxation achieved by gyrase inhibition (Supplementary Figures S5C and S6C), suggesting the involvement of promoter elements in such supercoiling sensitive regulation. To sum up, the activity of the topoI promoters is dynamically regulated and responsive to the alterations in the environmental conditions.

Upstream region of topoI promoter influences its activity

Analysis of the arrangement of the topoI gene and neighboring genes in the chromosomes of various mycobacterial species revealed a conserved pattern (Supplementary Figure S4). Importantly, the arrangement of upstream genes was highly conserved. One explanation for the retention of the same set of genes could be their role in the regulation of expression of the downstream genes. To monitor the effect of these genes on the topoI promoter activity, various deletion constructs of topoI upstream region were generated (Figure 3A), cloned into pSD5B reporter plasmid and their activity was evaluated by the β-galactosidase assay (Figure 3B). Deletion of a part of the immediate upstream gene MSMEG_6158 with its entire regulatory region resulted in ≈10-fold higher topoI promoter activity (530 bp construct) compared to the 1.5 kb construct retaining the intact MSMEG_6158 gene. However, the deletion of the next upstream gene MSMEG_6159 alone (1.2 kb construct) did not reveal significant change in the topoI promoter expression. The expression analysis of MSMEG_6158 indicated the high abundance of its transcripts (Supplementary Figure S8). Similarly, expression data from M. tuberculosis showed high transcription activity of Rv3647c which is a homolog of MSMEG_6158, located in the identical position in the M. tuberculosis chromosome (31). Analysis of MSMEG_6158 sequence did not reveal any known motifs for DNA binding or features of activator/repressor proteins. The higher transcriptional activity of the MSMEG_6158 could potentially be influencing the topology of the regulatory region of topoI leading to its reduced expression. Notably, the further deletion of the topoI upstream region led to the drastic reduction in the promoter activity (0.179 kb construct) (Figure 3B).

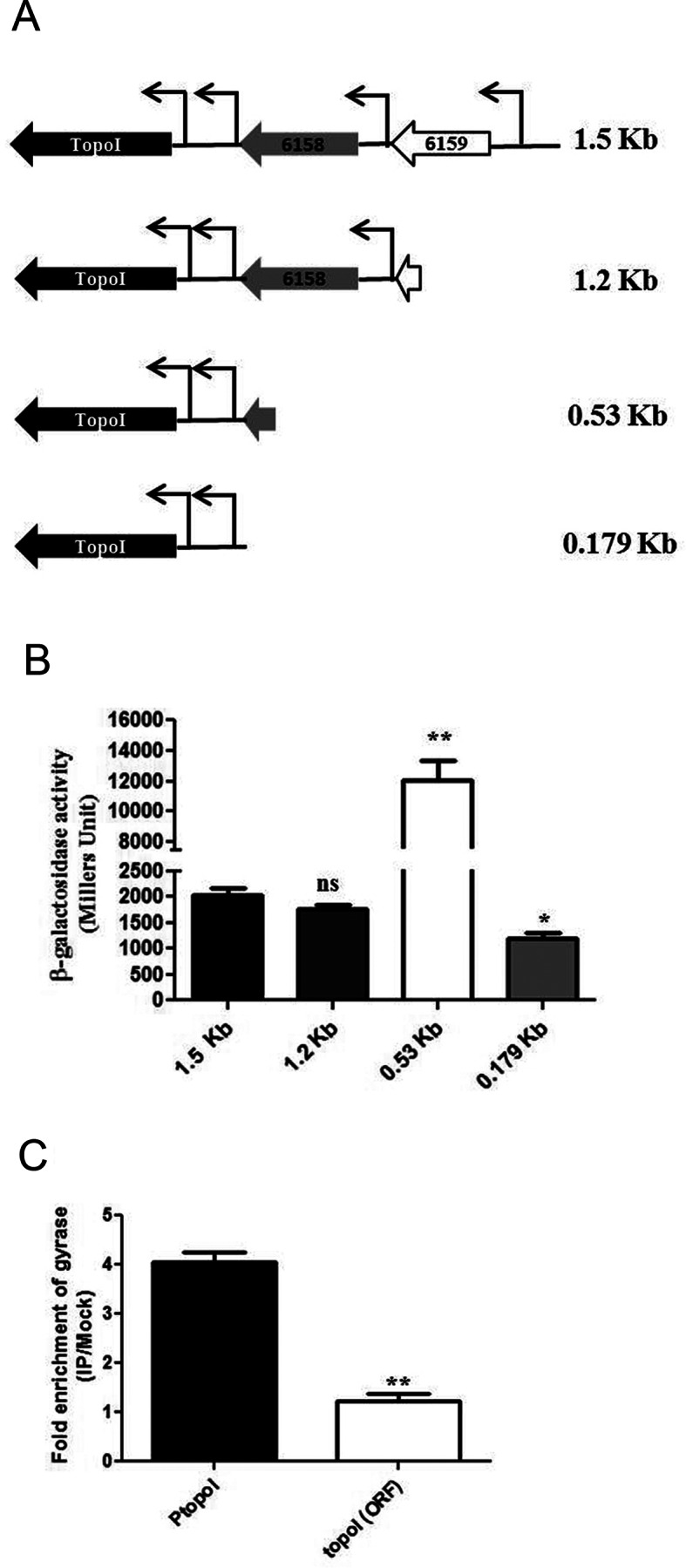

Figure 3.

Contribution of upstream elements on topoI promoter activity. (A) Schematic representation of the constructs generated for the study. (B) Measurement of the activity of various constructs harboring topoI promoter(s) by β-galactosidase assay. (C) Determination of gyrase binding on upstream region of topoI by ChIP-qRT PCR using the primers specific to the topoI upstream region. The enrichment values represent the enrichment of DNA fragment of interest (topoI promoter region and ORF) in immunoprecipitated (IP) sample over the mock. The error bars represent the SD obtained from three independent experiments.*P < 0.01, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001, ns: not significant (P > 0.1).

topoI upstream region recruits DNA gyrase

Higher transcriptional activity of the upstream gene of topoI promoter could result in the accumulation of positive supercoils (40,41) at the end of the MSMEG_6158 transcription unit located ahead of topoI thus perturbing the topology of the topoI regulatory region leading to the reduced expression. Negative supercoiling facilitates the topoI expression while the DNA relaxation has the opposite effect. Thus the optimal expression of the topoI gene requires the maintenance of a negative supercoiled state in the promoter and the neighboring sequences. To evaluate the role of gyrase in the stimulation of topoI expression as it is primarily responsible for introduction of negative supercoils in the chromosome, the binding of DNA gyrase in the regulatory region of topoI was assessed by ChIP-qRT PCR. High occupancy of DNA gyrase on the regulatory region of topoI and low occupancy on the gene ORF suggests the specific recruitment of DNA gyrase (Figure 3C). To identify the gyrase binding sites in the topoI upstream region, DNA bound gyrase was trapped with Moxifloxacin (Moxi) and ternary complexes were immunoprecipitated. The region between the 530 bp and 179 bp fragment of topoI upstream region recruits DNA gyrase and deletion of it abrogates the gyrase binding (Supplementary Figure S9A). Further, the reduced gyrase binding on the upstream region of 0.179 kb construct correlates with the significant drop in its promoter activity (Figure 3B).

To establish that DNA gyrase recruited at the topoI promoter is involved in the introduction of negative supercoiling in the promoter region, we have carried out biotinylated psoralen (bpsoralen) crosslinking was carried out as described (42). Psoralen preferentially intercalates into the negatively supercoiled DNA and thus the enhanced association of psoralen is an indicator of underwound DNA. When the gyrase activity was inhibited enrichment of bpsoralen-associated topoI promoter DNA was reduced (Supplementary Figure S9B) indicating the direct role of gyrase binding in the introduction of negative supercoils at topoI promoter(s). Overall, the gyrase recruitment at topoI regulatory regions appears to be essential for the maintenance of negative supercoiled status and hence the activity of its promoter.

Mapping of transcription start site (TSS) for topoI from M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis

The operation of SST of topoI raised a question on the regulatory mechanism and underlying elements for such regulation. In order to address this, mapping of TSS for the topoI mRNA from M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis was carried out. The RNA from the mycobacterial cells was subjected to primer extension and the size of the extension products was analyzed to map the TSS. Two extension products were identified in both M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis, indicating the existence of two promoters for the topoI transcription (Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure S10). Analysis of the topoI transcripts revealed the presence of longer 5′ leader sequences (Figure 4B and Supplementary Figure S10B). Notably, all the topoI transcripts, from both M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis, were significantly reduced upon novobiocin exposure suggesting the supercoiling sensitive expression of all the transcripts.

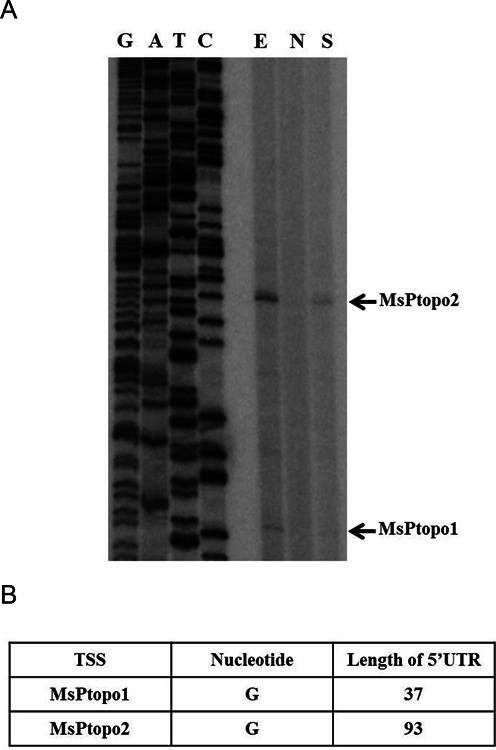

Figure 4.

Identification of Transcription Start Sites of topoI gene from M. smegmatis. (A) Primer extension analysis was carried out to map the TSS upstream of topoI as described in Materials and Methods. The primer extension products corresponding to the transcription start site for each promoter is indicated (arrows). E: exponential phase culture without novobiocin treatment, N: exponential phase culture treated novobiocin (100 μg/ml) for 3 h, S: stationary phase culture without novobiocin. (B) Table representing the 5′ UTR length and first nucleotide of the each transcripts.

Supercoiling sensitive transcription of topoI is conferred by its native promoter(s)

The results described so far indicated that the topoI promoter and upstream region contribute to the supercoiling sensitive expression of topoI. In order to evaluate the specificity of the topoI promoter(s) for such regulation, a strain was used where the native promoter(s) of topoI was replaced with a ptr promoter (Pptr) (Schematic Figure 5B) (43). Wild type (WT) M. smegmatis cells and the recombinant strain were treated with novobiocin and the expression of topoisomerases was monitored by immunoblotting. In both the WT and recombinant strain, the expression of gyrase was found to be increased upon treatment with novobiocin indicating the relaxation of the chromosome. The WT cells showed a decrease in the TopoI expression while the recombinant strain did not show a significant change in the expression of TopoI (Figure 5C) indicating that only the native topoI promoter(s) exhibited such a supercoiling sensitive response.

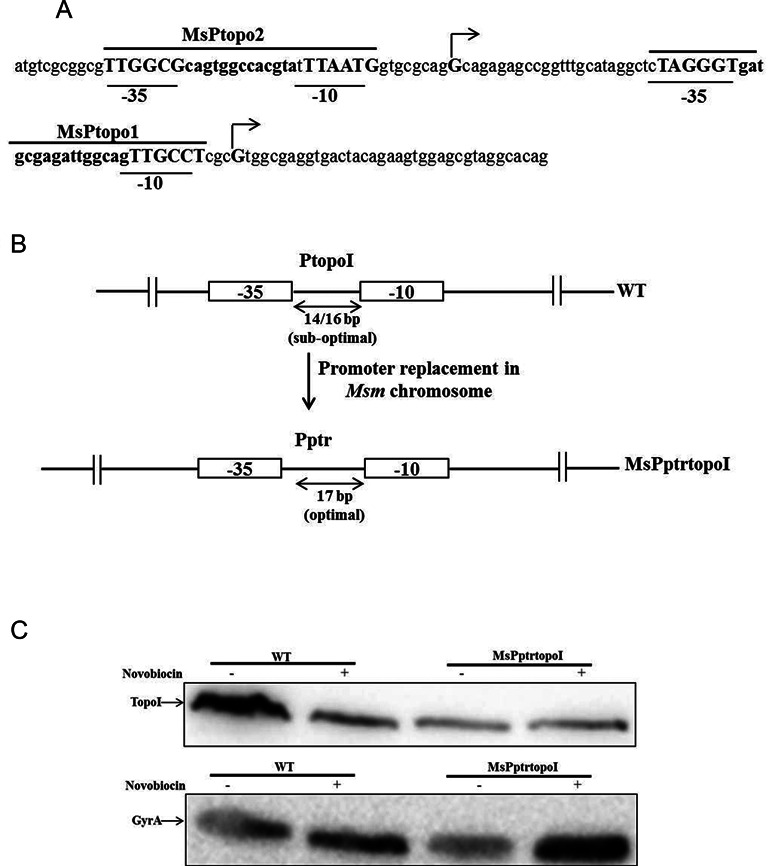

Figure 5.

Supercoiling sensitive expression of topoI is specific to native topoI promoter(s). (A) Promoter elements upstream to the start sites. Arrows indicates the transcription start sites. (B) Schematic showing the replacement of native promoter(s) of topoI with a ptr promoter (having optimally spaced −35 and −10 elements—17 bp spacer). (C) Immunoblot analysis of the TopoI and gyrase expression in native M. smegmatis cells and mutant strain with ptr promoter. The exponential phase recombinant and WT M. smegmatis cells were treated with novobiocin (100 μg/ml) for 6 h and processed for the immuno-detection of TopoI.

To decipher the underlying mechanism and regulatory elements involved in the regulation of topoI gene expression, promoter sequences of topoI from mycobacteria were analyzed. The spacer length between the −35 and −10 elements was found to be 14–16 nucleotides (Figure 5A). Due to the helical nature of DNA, the length of the spacer between the promoter elements is crucial to orient them into the same phase (44). According to this ‘twist’ model, promoters with optimal spacer length would show constitutive expression while the suboptimal spacing between the −10 and −35 motifs influence their relative orientation conferring supercoiling sensitivity. Thus, we reasoned that topoI promoter(s) may be subjected to similar supercoiling sensitive regulation. To validate the hypothesis we introduced 3 and 4 nucleotides in the spacer region of the native topoI promoter (major promoter MsPtopo2) by site directed mutagenesis using the 530 bp PtopoI-pSD5B construct as a template. Upon chromosome relaxation, the mutated constructs having 17/18 bp spacers did not show the drastic reduction in the promoter activity unlike the native promoter (Supplementary Figure S11) confirming the role of promoter elements in SST of topoI.

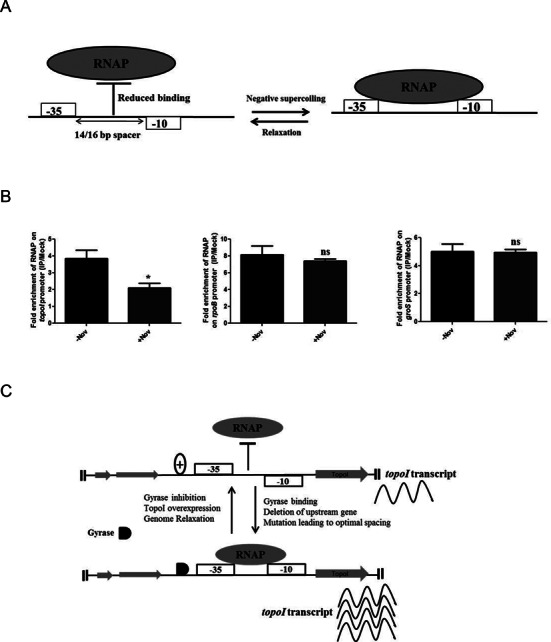

Chromosome relaxation affects the RNAP occupancy on the topoI promoter

The relative orientation between the −35 and −10 regions can strongly influence the ability of the RNA polymerase (RNAP) to locate and bind to a promoter (44). Supercoiling changes can twist/untwist the DNA and thus can change the orientation of the −35 and −10 elements, potentially affecting the interaction of RNAP with the promoter(s). The requirement of gyrase activity for the active expression of topoI promoters indicates that the negative supercoiling may provide an optimal template topology for the efficient binding of RNAP during the transcription initiation. To evaluate the effect of chromosome supercoiling on the binding of RNAP on the topoI promoter(s), the ChIP of RNAP was carried out to determine the RNAP occupancy on topoI promoter region. The exponential phase cells were treated with novobiocin and subjected to ChIP-qRT PCR analysis. Upon relaxation of the chromosome, the occupancy of RNAP on the topoI promoter(s) reduced significantly compared to the untreated cells (Figure 6). In contrast the occupancy of RNAP was not reduced on the promoter region of the supercoiling insensitive rpoB and groS genes. The occupancy of RNAP on the topoI promoter construct harboring optimal spacer length did not vary upon chromosome relaxation (Supplementary Figure S11C). These results imply that negative supercoiling would induce the topological changes in the DNA/promoter thus allowing optimal RNAP binding to the topoI promoter(s).

Figure 6.

Effect of chromosome relaxation on RNAP binding on TopoI promoter(s). (A) Schematic of the experimental design. Negative supercoiling may bring the −35 and −10 elements of topoI promoter(s) on the same phase of DNA thus enhancing the RNAP-promoter interaction. (B) Exponentially grown M. smegmatis cells were treated with novobiocin (100 μg/ml) for 6 h. The treated cells were subjected to ChIP using anti-RpoB antibody. The immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed for the enrichment of promoter region of various genes by qRT-PCR using primers flanking the promoter region. (C) Model representing the SST of TopoI. Sub-optimal spacer length between −10 and −35 elements align them out of phase affecting the optimal RNAP-promoter interaction. Additionally upstream gene transcription affects the DNA topology restricting the topoI activity. The negative supercoiling activity of DNA gyrase maintains the optimal topology of the topoI promoter aligning the −35 and −10 elements in the appropriate orientation required for the optimal transcription. Conditions leading to the chromosome relaxation reduce the topoI expression by altering optimal orientation of −35 and −10 elements. The error bars represent the SD obtained from three independent experiments.*P < 0.01, ns: not significant (P > 0.1).

DISCUSSION

The environmental conditions (24,45,46) tend to perturb the bacterial chromosome supercoiling influencing various cellular processes (39,47) and hence it is necessary to maintain supercoiling homeostasis of the chromosome. Topoisomerases ensure the topological homeostasis by introducing or removing the supercoils into DNA. Studies carried out in E. coli indicated the supercoiling sensitive expression of topoisomerases (10,12,14) which serves as a sensor of topological state of the chromosome. Here, we describe the supercoiling sensitive expression of topoI in mycobacteria and elucidate the underlying molecular mechanism. The role of high transcriptional activity of an upstream gene and the promoter architecture of topoI in the regulation is unraveled. Either ectopic overexpression of TopoI or inhibition of gyrase induced chromosome relaxation ensured that the endogenous TopoI expression is sensitive to the supercoiling status of the chromosome. Notably, in contrast to E. coli where overproduction of TopoI affected the plasmid topology marginally, overexpression of M. smegmatis TopoI lead to a significant level of relaxation of plasmid DNA. The enhanced relaxation achieved by mycobacterial TopoI could be associated with the high processivity of the mycobacterial TopoI (48). Being a sole relaxase in mycobacteria, it has to sense supercoiling states and respond to maintain the topological homeostasis. The topoI promoters were active only in mycobacteria (and not in E.coli) suggesting the unique organization of these promoters. The sequence of −35/−10 elements or overall architecture of topoI promoters may govern their recognition by mycobacterial transcription machinery but not E. coli. The analysis of the promoters after TSS mapping revealed unusual −35 and −10 elements (compared to E. coli) in both the mycobacteria which could confer the specificity observed. The species specific activity of mycobacterial promoters is not restricted to the topoI promoter (s). Both the M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis gyrase promoters were found to be active only in mycobacteria and not in E. coli (18,19). The recognition sequence of the mycobacterial topoI and DNA gyrase promoters (18,19) were significantly different from the σ70 consensus recognition (49) sequence of E. coli which may account for the difference in the expression of these promoters in the two bacterial genera. The importance of promoter architecture on transcription efficiency is well established (50,51). In addition to −10 and −35 elements, the role of discriminator region and spacer sequence between the two elements determines the promoter strength (52–54). Due to the helical nature of the DNA, increase or decrease in spacer length from 17(±1) would affect the orientation of the promoter elements rendering their activation sensitive to supercoiling. The alignment of −35 and −10 elements may contribute to the SST of the mycobacterial topoI. Replacement of native topoI promoter(s) with the Pptr which has a 17 bp spacer did not show supercoiling sensitivity strengthening the hypothesis that the SST is intrinsic to native topoI promoters. Due to the helical nature of DNA, the 17 bp spacing between the −35 and −10 elements aligns them in an orientation facilitating the promoter recognition and binding by RNAP (55). Under the situation where the spacing is different, the binding of RNAP may reduce and thus the introduction of supercoiling may facilitate initiation of transcription. ChIP analysis for the occupancy of RNAP on the topoI promoter(s) revealed the importance of supercoiling for the optimal binding of RNAP. Upon chromosome relaxation, the RNAP occupancy was decreased which could be a consequence of loss of optimal orientation of −35 and −10 elements upon chromosome relaxation. Studies with the E. coli tyrT indicated the role of supercoiling in its regulation. ‘Twist’ model proposed by Wang and Syvnanen suggested the role of suboptimal spacer in conferring the supercoiling sensitivity to various promoters. Based on the model, cold shock response of recA, osmotic shock response of proU, genes involved in the stringent response, regulation of histidine operon were predicted to be the supercoiling sensitive as these promoter(s) harbor suboptimal spacer length (44). Moreover, the sub-optimal spacing of tyrT promoter element (16 bp) was responsible for supercoiling sensitivity and insertion of a single nucleotide in the spacer rendered it supercoiling insensitive (56). Similarly, in Helicobacter pylori flaA having sub-optimal spacer length of 13 bp between the promoter elements, its expression was found to be sensitive to chromosome supercoiling (57). In all these cases, the impact of spacer length on the gene expression seems to be an attribute of promoter-RNAP interaction which needs to be further explored. The out of phase orientation of −35 and −10 elements would require additional factor (58,59) and/or supercoiled induced twisting (44) to bring them in phase allowing the optimal RNAP-promoter interaction as in the case of proU (60) and the present study. The negative supercoiling mediated regulatory mechanism of topoI deciphered here validates the ‘twist’ model proposed earlier (44).

The E. coli topoI promoters also exhibit the suboptimal spacer length (21) but their role has not been addressed in the supercoiling mediated regulation. Instead the role of a topology sensory protein Fis has been implicated in the topoI regulation (61). Fis binding on the topoI promoter was shown to modulate its activity differentially. Notably, Fis is absent in mycobacteria. In the absence of Fis, mycobacteria could have evolved the operation of suboptimal spacer based direct supercoiling sensitive regulatory mechanism of topoI expression.

In addition to the promoter architecture, transcriptional activity of the neighboring gene appears to influence the activity of the topoI promoter. The studies with a mutant leu-500 promoter provided one of the first evidences for the role of DNA topology in promoter activity (62,63). The transcriptional activity of a divergent promoter inserted upstream to the leu-500 led to the enhanced negative supercoiling resulting in higher expression of leu-500 (64). Further, the insertion of DNA sequences which are more prone to DNA melting upstream to the promoter enhances the transcriptional activity of the downstream promoter (65). According to the twin-supercoiled domain model of transcription, positive supercoils are generated ahead of the RNAP and negative supercoils upstream (40,41). The positive and negative waves of supercoiling would alter the local DNA topology (66) and thus influence the activity of the promoters residing in the region. In the present study, the deletion of gene upstream to topoI resulted in transcriptional inactivation leading to the reduced accumulation of positive supercoils ahead of topoI promoter. Hence, the activity of supercoiling sensitive topoI promoter was increased. The high occupancy of DNA gyrase at a region upstream to topoI implicates its role in the removal of positive supercoils and maintenance of optimal supercoiling around topoI regulatory region. Moreover, the negative supercoiling would also facilitate the melting of GC rich recognition and discriminator sequence of topoI promoter which is required for the optimal RNAP-promoter interaction (3,67–69). Therefore the inhibition of DNA gyrase by novobiocin would lead to chromosome relaxation resulting in reduced topoI transcription (Figure 6C).

Various environments and metabolic states influence the global chromosome supercoiling and thus the activity of supercoiling sensitive promoter(s). In E. coli and Salmonella, osmotic stress induced chromosome supercoiling resulted in enhanced expression of proU required for the adaptation (35). Analysis of the architecture of proU promoter revealed the presence of suboptimal spacer (16 bp) which was shown to confer supercoiling mediated osmoregulation of the gene (60). The topoI promoter exhibited the alteration in its activity in response to the environmental condition known to affect the supercoiling of the cellular DNA. The osmotic shock is known induce the supercoiling of DNA (35,36,70) and hence it led to the enhanced mycobacterial topoI promoter activity. On the other hand, contrary to E. coli paradigm high temperature resulted in a relaxation of the DNA and concomitant decrease in the topoI promoter activity. The observed discrepancy could be associated with the differences in the physiology and metabolism between the bacterial species. The perturbation of mycobacterial topoI promoter activity in response to the environmental cues suggested its role in sensing the environment and generating appropriate response for maintaining cellular homeostasis. Indeed, the chromosome supercoiling modulators topoI and DNA gyrase have been implicated in the regulation of various genes including the expression of virulent genes (39,71). The invasive phenotypes of Shigella flexneri and Salmonella Typhimurium were compromised in a topoI mutant (72,73). The hostile environment of the host may alter the chromosome supercoiling of the pathogenic species of mycobacteria which can be sensed by the topoI promoter. The subsequent response in the form of altered gene expression may be required for intracellular adaptation.

The alterations in the chromosome supercoiling can impact globally the gene expression profile across various bacterial species (74–76). The expression of TopoI and DNA gyrase is very well co-ordinated, i.e. decrease in gyrase activity would lead to the reduced expression of TopoI (6,15). The mutation of topoI in E. coli led to the compensatory mutations in the DNA gyrase suggesting the crucial requirement of the balancing activity of the supercoiling and relaxation enzymes (13). In M. smegmatis, by overexpressing the TopoI, the expression of DNA gyrase was also increased thus establishing the co-ordinated expression. The strict maintenance of the DNA supercoiling is achieved by the supercoiling sensitive regulatory circuits (RST versus SST) of both the topoisomerases. Another level of regulation of topoisomerase expression in E. coli is carried out by Fis which influences the expression of both DNA gyrase as well as topoI by modulation of promoter(s) activity (60,77). Mycobacteria lack Fis but HU was found to stimulate the TopoI relaxation activity by direct protein–protein interaction (78). TopoI-HU direct interaction was specific to mycobacteria suggesting the stringent regulation of TopoI activity in mycobacteria which could be associated with its regulatory role inside the cell.

To conclude, this study highlights the importance of supercoiling in the regulation of topoI expression in mycobacteria. The autoregulatory mechanism of topoI by sensing the alterations in chromosome supercoiling would ensure immediate response in fine tuning the enzyme levels as per cellular requirement. Given the supercoiling sensitivity of both E. coli and mycobacterial topoI promoters, the autoregulatory mechanism is likely to be conserved across eubacteria. The regulation of topoI by the chromosome supercoiling is influenced by a combination of factors such as sequence of promoter elements, spacer length between the elements, neighboring gene expression status and topology modulatory proteins. The contributions of individual factors in the SST of topoI need to be dissected by extensive mutational analysis and genetic approaches.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of VN laboratory for valuable suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript. Sohini Ganguly is acknowledged for the technical assistance. We thank Prof. Riccardo Manganelli for providing the plasmid construct (pFRA50) containing ptr promoter.

FUNDING

Department of Biotechnology, Government of India. V.N. is J. C. Bose Fellow of Department of Science and Technology, Government of India. Funding for open access charge: J. C. Bose Fellowship of Department of Science and Technology, Government of India.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Champoux J.J. DNA topoisomerases: structure, function, and mechanism. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001;70:369–413. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang J.C. Cellular roles of DNA topoisomerases: a molecular perspective. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;3:430–440. doi: 10.1038/nrm831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drew H.R., Weeks J.R., Travers A.A. Negative supercoiling induces spontaneous unwinding of a bacterial promoter. EMBO J. 1985;4:1025–1032. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03734.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatfield G.W., Benham C.J. DNA topology-mediated control of global gene expression in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2002;36:175–203. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.032902.111815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masse E., Drolet M. Relaxation of transcription-induced negative supercoiling is an essential function of Escherichia coli DNA topoisomerase I. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:16654–16658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.16654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pruss G.J., Manes S.H., Drlica K. Escherichia coli DNA topoisomerase I mutants: increased supercoiling is corrected by mutations near gyrase genes. Cell. 1982;31:35–42. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90402-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson S.M., Higgins C.F., Lilley D.M. The genetic control of DNA supercoiling in Salmonella typhimurium. EMBO J. 1984;3:1745–1752. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zechiedrich E.L., Khodursky A.B., Cozzarelli N.R. Topoisomerase IV, not gyrase, decatenates products of site-specific recombination in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2580–2592. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.19.2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snoep J.L., van der Weijden C.C., Andersen H.W., Westerhoff H.V., Jensen P.R. DNA supercoiling in Escherichia coli is under tight and subtle homeostatic control, involving gene-expression and metabolic regulation of both topoisomerase I and DNA gyrase. FEBS J. 2002;269:1662–1669. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2002.02803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Menzel R., Gellert M. Modulation of transcription by DNA supercoiling: a deletion analysis of the Escherichia coli gyrA and gyrB promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1987;84:4185–4189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.12.4185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tse-Dinh Y.C., Beran R.K. Multiple promoters for transcription of the Escherichia coli DNA topoisomerase I gene and their regulation by DNA supercoiling. J. Mol. Biol. 1988;202:735–742. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90554-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tse-Dinh Y.C. Regulation of the Escherichia coli DNA topoisomerase I gene by DNA supercoiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:4751–4763. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.13.4751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiNardo S., Voelkel K.A., Sternglanz R., Reynolds A.E., Wright A. Escherichia coli DNA topoisomerase I mutants have compensatory mutations in DNA gyrase genes. Cell. 1982;31:43–51. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menzel R., Gellert M. Regulation of the genes for E. coli DNA gyrase: homeostatic control of DNA supercoiling. Cell. 1983;34:105–113. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menzel R., Gellert M. Fusions of the Escherichia coli gyrA and gyrB control regions to the galactokinase gene are inducible by coumermycin treatment. J. Bacteriol. 1987;169:1272–1278. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.3.1272-1278.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Straney R., Krah R., Menzel R. Mutations in the -10 TATAAT sequence of the gyrA promoter affect both promoter strength and sensitivity to DNA supercoiling. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:5999–6006. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.5999-6006.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unniraman S., Nagaraja V. Axial distortion as a sensor of supercoil changes: a molecular model for the homeostatic regulation of DNA gyrase. J. Genet. 2001;80:119–124. doi: 10.1007/BF02717907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unniraman S., Chatterji M., Nagaraja V. DNA gyrase genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a single operon driven by multiple promoters. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:5449–5456. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.19.5449-5456.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Unniraman S., Nagaraja V. Regulation of DNA gyrase operon in Mycobacterium smegmatis: a distinct mechanism of relaxation stimulated transcription. Genes Cells. 1999;4:697–706. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1999.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lesley S.A., Jovanovich S.B., Tse-Dinh Y.C., Burgess R.R. Identification of a heat shock promoter in the topA gene of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1990;172:6871–6874. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6871-6874.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qi H., Menzel R., Tse-Dinh Y.C. Regulation of Escherichia coli topA gene transcription: involvement of a sigmaS-dependent promoter. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;267:481–489. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schnappinger D., Ehrt S., Voskuil M.I., Liu Y., Mangan J.A., Monahan I.M., Dolganov G., Efron B., Butcher P.D., Nathan C., et al. Transcriptional Adaptation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis within Macrophages: Insights into the Phagosomal Environment. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:693–704. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Triccas J.A., Gicquel B. Life on the inside: probing Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene expression during infection. Immunol. Cell. Biol. 2000;78:311–317. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2000.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dorman C.J. DNA supercoiling and environmental regulation of gene expression in pathogenic bacteria. Infect. Immun. 1991;59:745–749. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.3.745-749.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmed W., Menon S., Godbole A.A., Karthik P.V., Nagaraja V. Conditional silencing of topoisomerase I gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis validates its essentiality for cell survival. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2014;353:116–123. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blokpoel M.C., Murphy H.N., O'Toole R., Wiles S., Runn E.S., Stewart G.R., Young D.B., Robertson B.D. Tetracycline-inducible gene regulation in mycobacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e22. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jain P., Nagaraja V. Indispensable, functionally complementing N and C-terminal domains constitute site-specific topoisomerase I. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;357:1409–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jain S., Kaushal D., DasGupta S.K., Tyagi A.K. Construction of shuttle vectors for genetic manipulation and molecular analysis of mycobacteria. Gene. 1997;190:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00746-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu Z., Colosimo A., Gruenert D.C. Site-directed mutagenesis using the megaprimer method. Methods Mol. Biol. 2003;235:203–207. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-409-3:203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller J.H. A Short Course in Bacterial Genetics: a Laboratory Manual and Handbook for Escherichia Coli and Related Bacteria. NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uplekar S., Rougemont J., Cole S.T., Sala C. High-resolution transcriptome and genome-wide dynamics of RNA polymerase and NusA in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;41:961–977. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pruss G.J., Franco R.J., Chevalier S.G., Manes S.H., Drlica K. Effects of DNA gyrase inhibitors in Escherichia coli topoisomerase I mutants. J. Bacteriol. 1986;168:276–282. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.1.276-282.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drlica K., Snyder M. Superhelical Escherichia coli DNA: relaxation by coumermycin. J. Mol. Biol. 1978;120:145–154. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmed W., Bhat A.G., Leelaram M.N., Menon S., Nagaraja V. Carboxyl terminal domain basic amino acids of mycobacterial topoisomerase I bind DNA to promote strand passage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:7462–7471. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higgins C.F., Dorman C.J., Stirling D.A., Waddell L., Booth I.R., May G., Bremer E. A physiological role for DNA supercoiling in the osmotic regulation of gene expression in S. typhimurium and E. coli. Cell. 1988;52:569–584. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90470-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hsieh L.S., Rouviere-Yaniv J., Drlica K. Bacterial DNA supercoiling and [ATP]/[ADP] ratio: changes associated with salt shock. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:3914–3917. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.12.3914-3917.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldstein E., Drlica K. Regulation of bacterial DNA supercoiling: plasmid linking numbers vary with growth temperature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1984;81:4046–4050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.13.4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mojica F.J., Charbonnier F., Juez G., Rodriguez-Valera F., Forterre P. Effects of salt and temperature on plasmid topology in the halophilic archaeon Haloferax volcanii. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:4966–4973. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.16.4966-4973.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dorman C.J., Ni Bhriain N., Higgins C.F. DNA supercoiling and environmental regulation of virulence gene expression in Shigella flexneri. Nature. 1990;344:789–792. doi: 10.1038/344789a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rahmouni A.R., Wells R.D. Direct evidence for the effect of transcription on local DNA supercoiling in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;223:131–144. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90721-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu L.F., Wang J.C. Supercoiling of the DNA template during transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1987;84:7024–7027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naughton C., Avlonitis N., Corless S., Prendergast J.G., Mati I.K., Eijk P.P., Cockroft S.L., Bradley M., Ylstra B., Gilbert N. Transcription forms and remodels supercoiling domains unfolding large-scale chromatin structures. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:387–395. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boldrin F., Casonato S., Dainese E., Sala C., Dhar N., Palu G., Riccardi G., Cole S.T., Manganelli R. Development of a repressible mycobacterial promoter system based on two transcriptional repressors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e134. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang J.Y., Syvanen M. DNA twist as a transcriptional sensor for environmental changes. Mol. Microbiol. 1992;6:1861–1866. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Westerhoff H.V., van Workum M. Control of DNA structure and gene expression. Biomed. Biochim. Acta. 1990;49:839–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hsieh L.S., Burger R.M., Drlica K. Bacterial DNA supercoiling and [ATP]/[ADP]. Changes associated with a transition to anaerobic growth. J. Mol.Biol. 1991;219:443–450. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dorman C.J. DNA supercoiling and bacterial gene expression. Sci. Prog. 2006;89:151–166. doi: 10.3184/003685006783238317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bhaduri T., Bagui T.K., Sikder D., Nagaraja V. DNA topoisomerase I from Mycobacterium smegmatis. An enzyme with distinct features. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:13925–13932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harley C.B., Reynolds R.P. Analysis of E. coli promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:2343–2361. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.5.2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gourse R.L., Gaal T., Aiyar S.E., Barker M.M., Estrem S.T., Hirvonen C.A., Ross W. Strength and regulation without transcription factors: lessons from bacterial rRNA promoters. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1998;63:131–139. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ross W., Aiyar S.E., Salomon J., Gourse R.L. Escherichia coli promoters with UP elements of different strengths: modular structure of bacterial promoters. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:5375–5383. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.20.5375-5383.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jensen P.R., Hammer K. The sequence of spacers between the consensus sequences modulates the strength of prokaryotic promoters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998;64:82–87. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.1.82-87.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pemberton I.K., Muskhelishvili G., Travers A.A., Buckle M. The G+C-rich discriminator region of the tyrT promoter antagonises the formation of stable preinitiation complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;299:859–864. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perez-Martin J., Rojo F., de Lorenzo V. Promoters responsive to DNA bending: a common theme in prokaryotic gene expression. Microbiol. Rev. 1994;58:268–290. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.2.268-290.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aoyama T., Takanami M. Supercoiling response of E. coli promoters with different spacer lengths. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1988;949:311–317. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(88)90157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Auner H., Buckle M., Deufel A., Kutateladze T., Lazarus L., Mavathur R., Muskhelishvili G., Pemberton I., Schneider R., Travers A. Mechanism of transcriptional activation by FIS: role of core promoter structure and DNA topology. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;331:331–344. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00727-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ye F., Brauer T., Niehus E., Drlica K., Josenhans C., Suerbaum S. Flagellar and global gene regulation in Helicobacter pylori modulated by changes in DNA supercoiling. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2007;297:65–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Basak S., Nagaraja V. DNA unwinding mechanism for the transcriptional activation of momP1 promoter by the transactivator protein C of bacteriophage Mu. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:46941–46945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107476200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ansari A.Z., Chael M.L., O'Halloran T.V. Allosteric underwinding of DNA is a critical step in positive control of transcription by Hg-MerR. Nature. 1992;355:87–89. doi: 10.1038/355087a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jordi B.J., Owen-Hughes T.A., Hulton C.S., Higgins C.F. DNA twist, flexibility and transcription of the osmoregulated proU promoter of Salmonella typhimurium. EMBO J. 1995;14:5690–5700. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00256.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weinstein-Fischer D., Altuvia S. Differential regulation of Escherichia coli topoisomerase I by Fis. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;63:1131–1144. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Free A., Dorman C.J. Escherichia coli tyrT gene transcription is sensitive to DNA supercoiling in its native chromosomal context: effect of DNA topoisomerase IV overexpression on tyrT promoter function. Mol. Microbiol. 1994;14:151–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Richardson S.M., Higgins C.F., Lilley D.M. DNA supercoiling and the leu-500 promoter mutation of Salmonella typhimurium. EMBO J. 1988;7:1863–1869. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03019.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tan J., Shu L., Wu H.Y. Activation of the leu-500 promoter by adjacent transcription. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:1077–1086. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.4.1077-1086.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Klein R.D., Wells R.D. Effects of Neighboring DNA homopolymers on the biochemical and physical properties of the Escherichia coli lactose promoter. II. In vitro transcription analyses. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:12962–12969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peck L.J., Wang J.C. Transcriptional block caused by a negative supercoiling induced structural change in an alternating CG sequence. Cell. 1985;40:129–137. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mizutani M., Ohta T., Watanabe H., Handa H., Hirose S. Negative supercoiling of DNA facilitates an interaction between transcription factor IID and the fibroin gene promoter. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:718–722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen D., Bowater R., Dorman C.J., Lilley D.M. Activity of a plasmid-borne leu-500 promoter depends on the transcription and translation of an adjacent gene. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:8784–8788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Travers A.A. Promoter sequence for stringent control of bacterial ribonucleic acid synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 1980;141:973–976. doi: 10.1128/jb.141.2.973-976.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McClellan J.A., Boublikova P., Palecek E., Lilley D.M. Superhelical torsion in cellular DNA responds directly to environmental and genetic factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:8373–8377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dove S.L., Dorman C.J. The site-specific recombination system regulating expression of the type 1 fimbrial subunit gene of Escherichia coli is sensitive to changes in DNA supercoiling. Mol. Microbiol. 1994;14:975–988. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Galan J.E., Curtiss R. 3rd. Expression of Salmonella typhimurium genes required for invasion is regulated by changes in DNA supercoiling. Infect. Immun. 1990;58:1879–1885. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1879-1885.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ni Bhriain N., Dorman C.J. Isolation and characterization of a topA mutant of Shigella flexneri. Mol. Microbiol. 1993;7:351–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ferrandiz M.J., Martin-Galiano A.J., Schvartzman J.B., de la Campa A.G. The genome of Streptococcus pneumoniae is organized in topology-reacting gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:3570–3581. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gmuender H., Kuratli K., Di Padova K., Gray C.P., Keck W., Evers S. Gene expression changes triggered by exposure of Haemophilus influenzae to novobiocin or ciprofloxacin: combined transcription and translation analysis. Genome Res. 2001;11:28–42. doi: 10.1101/gr.157701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Peter B.J., Arsuaga J., Breier A.M., Khodursky A.B., Brown P.O., Cozzarelli N.R. Genomic transcriptional response to loss of chromosomal supercoiling in Escherichia coli. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R87. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-11-r87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Blot N., Mavathur R., Geertz M., Travers A., Muskhelishvili G. Homeostatic regulation of supercoiling sensitivity coordinates transcription of the bacterial genome. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:710–715. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ghosh S., Mallick B., Nagaraja V. Direct regulation of topoisomerase activity by a nucleoid-associated protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:11156–11165. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.