Abstract

Background

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a novel group of universally present, non-coding RNAs (>200 nt) that are increasingly recognized as key regulators of many physiological and pathological processes.

Scope of review

Recent publications have shown that lncRNAs influence lipid homeostasis by controlling lipid metabolism in the liver and by regulating adipogenesis. lncRNAs control lipid metabolism-related gene expression by either base-pairing with RNA and DNA or by binding to proteins.

Major conclusions

The recent advances and future prospects in understanding the roles of lncRNAs in lipid homeostasis are discussed.

Keywords: lncRNA, Liver, Lipid metabolism, Adipose tissue, Adipogenesis

1. Introduction

Obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D) are epidemic health problems that affect millions of people worldwide. Fat accumulation is determined by the balance between anabolic (adipogenesis and lipogenesis) and catabolic (lipolysis, fatty acid β-oxidation, and thermogenesis) processes. Adipogenesis is the process by which preadipocytes develop into mature white or brown adipocytes, contributing to energy balance [1]. Lipogenesis is the process of fatty acid synthesis and subsequent triglyceride synthesis in both white adipose tissue (WAT) and liver. Lipogenesis is triggered by circulating insulin and ingestion of nutrients [2]. Conversely, other hormones and exercise induce lipolysis, the breakdown of triglycerides into glycerol and free fatty acids, in both WAT and muscle [3], [4]. Free fatty acids released into the circulation during lipolysis are subsequently taken up by liver, muscle, and brown adipose tissue (BAT) as an energy source for β-oxidation [4]. Lastly, adaptive thermogenesis in BAT is a catabolic process in which oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid β-oxidation are uncoupled to generate heat [5], [6]. All of these processes are initiated and regulated by hormones, nutrients, and/or environmental stress, transduced by signal pathways, and controlled by transcription factors [2], [4], [6]. The balance of these processes is critical for maintaining normal adiposity and regulating systemic lipid metabolism. All too often, however, dysregulation of these processes leads to increased adiposity, dyslipidemia, and metabolic perturbations that can accelerate diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Emerging studies now suggest that non-coding RNAs are also key regulators of lipid homeostasis. More than 90% of the human genome is likely to be transcribed; yet less than 2% of the genome encodes approximately 20,000 proteins (International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium 2004). This leaves the balance of the human genome (∼98%) to be transcribed into thousands of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs). ncRNAs are classified into two main subgroups: short ncRNAs (<200 nt) and long ncRNAs (>200 nt). Short ncRNAs include microRNAs (miRNAs), which regulate many biological processes by inducing mRNA degradation via the RNA interference pathway. miRNAs are well studied and have been implicated in human diseases including cancer [7], cardiovascular disease [8], diabetes [9], and neurodegenerative disorders [10]. Furthermore, miRNAs regulate lipid metabolism and adipogenesis [11], [12]. By contrast, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are less well-studied. The most recent release from GenCode (version 22) has annotated ∼15,900 lncRNA genes in humans. lncRNAs are categorized based on genome location into intergenic, intronic, antisense and enhancer lncRNAs [13]. Multiple studies have shown that many lncRNAs are regulated during development, exhibit cell type-specific expression patterns, localize to specific subcellular compartments, and are associated with human diseases such as cancer [14] and diabetes [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]. As summarized in Table 1, there is now accumulating evidence that lncRNAs are important regulators of lipid metabolism and adipogenesis [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26]. Recent studies that implicate lncRNAs in the regulation of lipid metabolism in the liver and adipogenesis are reviewed here.

Table 1.

Functional lncRNAs involved in lipid metabolism and adipogenesis.

| Name | Tissue/cell type | Loss-of-function phenotype | Gain-of-function phenotype | Assays | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lncLSTR | Liver | Reduce plasma TG level | Knockdown | [23] | |

| HULC | Hepatoma cell | Increase triglyceride and cholesterol levels | Overexpression | [30] | |

| APOA1-AS | Liver | Increase APOA1 expression both in vitro and in vivo | Knockdown | [31] | |

| DYNLRB2-2 | Macrophage | Decrease cellular cholesterol level, increase APOA1 mediated cholesterol efflux | Overexpression | [34] | |

| SRA | Fat | Reduce adipose size and liver TG level | Knockout | [37], [38], [39] | |

| ADINR | 3T3-L1 cell | Reduce adipogenesis | Knockdown | [41] | |

| NEAT1 | 3T3-L1 cell | Increase adipogenesis | Overexpression | [42], [43] | |

| HOTAIR | Gluteal adipose tissue | Increase adipogenesis | Overexpression | [44] | |

| lnc-BATE1 | Brown adipose tissue | Reduce BAT activation | knockdown | [35] | |

| Blnc1 | Brown adipose tissue/epididymal white adipose tissue | Reduce brown adipogenesis | Stimulate brown adipogenesis | Knockdown/overexpression | [26] |

1.1. Tissue specific lncRNAs

Unlike mRNAs, lncRNAs are poorly conserved. lncRNAs are expressed in a species-, cell-, tissue-, and developmental stage-specific manner. There are approximately 11,000 primate-specific lncRNAs but only about 425 highly conserved lncRNAs. Conserved lncRNAs appear to predominantly regulate embryonic development [27]. Notably, each tissue generates unique lncRNAs during development [27]. For example, in mice, about 1109 polyadenylated lncRNAs are expressed in erythroblasts, megakaryocytes, and megakaryocyte-erythroid precursors, whereas 594 lncRNAs are expressed in human erythroblasts [28]. Collectively, 53.6% of lncRNAs in megakaryocyte-erythroid precursors are conserved between mouse and human, whereas only 15% of mouse erythroid lncRNAs are expressed in human erythroblasts [28], indicating that the conservation of lncRNAs is highly dependent on both species and development stage.

Each tissue has its own catalog of specific lncRNAs, which may contribute to the unique function of each tissue. Liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue are three major metabolic tissues controlling lipid metabolism. An analysis of a dataset of multi-tissue gene expression profiles identified 30 lncRNAs that are enriched in liver, muscle, or adipose tissues [23]. These lncRNAs may regulate lipid metabolism in these tissues.

1.2. lncRNAs regulate lipid metabolism in the liver

Analysis of liver-enriched lncRNAs identifies lncLSTR as a putative regulator of plasma triglyceride (TG) levels [23]. Liver-specific knockdown of lncLSTR increases ApoC2 expression and LPL activities, enhances plasma TG clearance, and ultimately results in decreased plasma TG [23]. However, knockdown of lncLSTR in primary hepatocytes fails to increase ApoC2 expression, suggesting that another mediator exists in the liver cells. Liver-specific knockdown of lncLSTR decreases the expression of Cyp8b1, increases the ratio of muricholic acid (MA) and cholic acid (CA) in bile acid, and enhances FXR activity, leading to increased ApoC2 expression [23]. Mechanistically, lncLSTR is shown to directly bind to TDP43 and inhibit Cyp8b1 expression [23]. Another lncRNA, HULC, which is abnormally overexpressed in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [29], has been shown to increase triglyceride and cholesterol levels by activating PPARα and ACSL1 in hepatoma cells [30]. Together, these studies demonstrate that liver-enriched lncRNAs regulate lipid metabolism in the liver.

Another potential group of lncRNAs that regulates lipid metabolism is natural antisense transcripts (NATs). About 70% of lncRNAs are NATs, which regulate sense gene expression in a positive or negative manner [31]. APOA1-AS has been shown to negatively regulate APOA1 expression both in vitro and in vivo [31]. Moreover, APOA1-AS regulates different histone methylation patterns that activate or suppress gene expression. Knockdown of APOA1-AS increases the level of H3K4-me3, decreases the level of H3K27-me3, but does not alter the level of H3K9-me3 at APO gene cluster, leading to increased expression of APOA1, APOA4 and APOC3 [31]. APOA1 is a major component of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), protecting against cardiovascular disease [32], making APOA1-AS a potential therapeutic target for treating cardiovascular disease.

The expression of many lncRNAs can be induced by hormones [33], ligands [26], or lipoprotein [34], and these lncRNAs could regulate lipid metabolism. For example, oxidized LDL (Ox-LDL) significantly induces long intervening noncoding RNA (lincRNA)-DYNLRB2-2 expression, resulting in the upregulation of GPR119 and ABCA1 expression through the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor signaling pathway in THP-1 macrophage-derived foam cells [34]. As a negative feedback, GPR119 significantly decreases cellular cholesterol content and increases APOA1-mediated cholesterol efflux in the liver, reducing atherosclerosis in APOE knockout mice [34]. This study shows that inducible lncRNAs regulate lipid metabolism.

1.3. lncRNAs regulate adipogenesis

Adipocytes, including white, brown, and beige, play important roles in lipid storage or clearance. White adipocytes are the major constituent of white adipose tissue (WAT), controlling the storage of triacylglycerol [1]. Brown adipose tissue (BAT) and beige fat are responsible for thermogenesis. BAT is an important tissue controlling plasma lipid clearance in response to cold stimulation [5]. Both white and brown adipogenesis are tightly controlled by signal pathways, transcription factors, miRNA, and lncRNAs [1], [11], [26], [35], [36].

The first evidence of a potential role for lncRNAs in adipogenesis was reported by Xu et al [37]. The non-coding RNA, steroid receptor RNA activator (SRA), promotes adipogenesis in vitro through regulation of PPARγ and P38/JNK phosphorylation [37], [38]. Genetic deletion of SRA protects high fat diet induced obesity and fatty liver disease, reduces the size of adipocytes, and improves glucose tolerance [39].

To identify adipogenesis associated lncRNAs, transcriptomic analyses of primary brown and white adipocytes, preadipocytes, and cultured adipocytes have been performed [24], [26], [35], [40]. A total of 175 lncRNAs were found to be significantly up- or down-regulated, by more than two-fold, during differentiation of both brown and white adipocytes [40]. Many lncRNAs are adipose-enriched and strongly induced during adipogenesis. Key transcription factors such as PPARγ and C/EBPα not only control mRNA expression related to adipogenesis but also regulate lncRNA expression during adipogenesis [40]. PPARγ is physically bound within the promoter region of 23 (13%) of the 175 lncRNAs while C/EBPα is bound upstream of 34 up-regulated lncRNAs (19%) during adipogenesis [40].

Some lncRNAs have been shown to regulate adipogenesis by loss- and gain-of-function assays [40], [41]. lncRNA ADINR specifically binds to PA1 and recruits MLL3/4 histone methyl-transferase complexes to increase H3K4me3 and decrease H3K27me3 histone modification in the C/EBPα locus, leading to transcriptional activation of C/EBPα and increased adipogenesis [41]. lncRNA NEAT1 regulates PPARγ2 splicing during adipogenesis [42]. It also mediates miR-140 induced adipogenesis [43]. In human, lncRNA HOTAIR is highly expressed in gluteal but not in abdominal adipose tissue [44]. Ectopic expression of HOTAIR in abdominal preadipocytes increases cell differentiation by inducing expression of PPARγ and LPL [44]. These data demonstrate that lncRNAs regulate white adipogenesis through lncRNA-protein and lncRNA-miRNA interactions.

To identify lncRNAs associated with adipogenesis in brown fat, RNA-seq and microarray have been performed by several independent groups [24], [26], [45], [46]. One study shows that 127 lncRNAs are BAT-specific, induced during brown adipose differentiation, and targeted by key transcription factors such as PPARγ, C/EBPα, and C/EBPβ [35]. One of these lncRNAs, lnc-BATE1, is essential to maintain BAT identity and thermogenic capacity. Knockdown of lnc-BATE1 impairs the activation of BAT. lnc-BATE1 binds to heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U, and both are required for brown adipogenesis [35]. Another independent study revealed a cluster of 21 lncRNAs, the expression of which is enriched in BAT and induced during brown adipocyte differentiation [26]. Among these lncRNAs, Blnc1 was shown to be a key regulator of brown adipogenesis [26]. Knockdown of Blnc1 inhibits brown adipogenesis, while overexpression of Blnc1 enhances lipid accumulation in differentiated brown adipocytes [26]. Mechanistically, Blnc1 forms a ribonucleoprotein complex with transcription factor EBF2 to stimulate the thermogenic gene program, driving brown adipogenesis [26]. These studies show that lncRNAs induced during adipogenesis regulate adipogenesis and thermogenesis through lncRNA-protein interactions.

1.4. Future perspectives

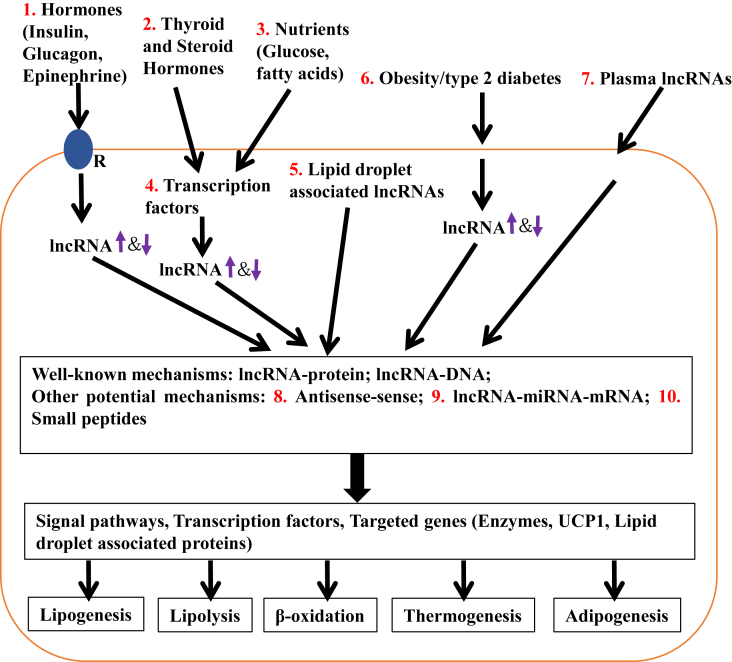

Many lncRNAs associated with lipid metabolism and adipogenesis have been identified through RNA-seq and bioinformatics analyses. The roles of these lncRNAs are beginning to be classified. However, we are still at the tip of the iceberg regarding our understanding of lncRNAs in the regulation of lipid metabolism, and numerous future potential research directions should be taken if we are to fully understand how lncRNAs regulate lipid metabolism at the cellular and organismal levels (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Perspectives of lncRNAs in the regulation of lipid metabolism. Fat accumulation is determined by the balance between anabolic (adipogenesis and lipogenesis) and catabolic (lipolysis, fatty acid β-oxidation, and thermogenesis) processes that are mainly controlled by WAT, BAT, liver and muscle. These processes are initiated and regulated by hormones, nutrients, and/or environmental stress, transduced by signal pathways, controlled by transcription factors, and exerted by multiple enzymes, UCP1, and lipid droplet associated proteins. lncRNAs may be involved in all these processes. It is very important to identify lncRNAs that are induced by hormones (e.g. Insulin, Glucagon, and Epinephrine) (1), thyroid and steroid hormones or nutrients/transcription factors (2, 3, 4), and those that are associated with lipid droplets (5) and obesity/type 2 diabetes (6), and plasma lncRNAs (7). These lncRNAs may regulate lipid metabolism through well-known or other potential mechanisms, including lncRNA-protein, lncRNA-DNA, antisense-sense (8), and lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA interactions (9), and expression of small peptides (10).

First, identifying the hormonal regulation of lncRNAs during fat accumulation is very important. Lipogenesis, lipolysis, β-oxidation, adipogenesis, and thermogenesis are highly regulated processes. It is likely that many of the same hormones and signaling pathways that regulate lipid metabolism (e.g. insulin [2], [47], glucocorticoids [47], GLP-1 [48], thyroid hormone [49], adiponectin [50], and leptin [51], [52]) influence the expression and activity of lncRNAs. Similarly, nutritional inputs (glucose and fatty acids) may also regulate key lncRNAs to control lipogenesis. One could envision a scenario in which lncRNAs might be induced by key transcription factors that control metabolism (e.g. SREBP1 [53], ChREBP [54], [55], LXRs [56], [57], FXR [56], [57], PPARγ [58], [59], and PPARα [60], [61]). Subsequently, subsets of lncRNAs could either mediate lipogenesis or β-oxidation by fine-tuning gene expression programs or by providing feedback to regulate the activity of metabolic transcription factors.

Second, given that lipid droplet formation in adipocytes and at ectopic sites (muscle and liver) plays an important role in physiological and pathological conditions of obesity [62], [63], [64], it is important to identify lncRNAs that regulate the formation of lipid droplets. Regulation of this process by lncRNAs may be achieved by several means. For example, previous studies have indicated that lncRNAs might express small peptides [65], [66], which could alter lipid droplet formation. miRNAs also are important to lipid metabolism [11], [12], and many publications show that lncRNAs can reduce miRNA levels by acting either as sponges or through base-pairing with primary miRNAs to block their processing into mature miRNAs. Therefore, lncRNAs and miRNAs may interact to regulate or dysregulate genes that encode key lipid-binding proteins and/or other regulators of lipid droplet formation. Along these same lines, it will be important to identify more natural antisense transcripts (NATs) associated with lipid metabolism. About 70% of lncRNAs are NATs that regulate gene expression in a positive or negative manner. NATs are good therapeutic targets for human diseases, including immune diseases [31], [67] and cardiovascular diseases [31]. However, only one NAT, APOA1-AS, has been identified as a negative regulator of APOA1 expression both in vitro and in vivo [31].

Third, it will be very important to demonstrate that aberrant lncRNA expression is linked to the development of lipid accumulation that accompanies obesity, diabetes, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in human populations. Clinically, circulating lncRNAs serve as biomarkers for cancer [68], [69], heart failure [70], and kidney injury [71]. So it is possible to monitor biologically relevant lncRNAs non-invasively. However, using lncRNAs as biomarkers for obesity is not as critical. Recent data show that miRNA and other noncoding RNA in plasma exosomes regulate the immune response [72], [73]. It would be very interesting to test whether plasma lncRNAs regulate lipid metabolism in liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue. Moreover, it would be interesting to determine whether lncRNAs that regulate lipogenesis, lipolysis, β-oxidation, adipogenesis, and thermogenesis in cells can serve as meaningful biomarkers to monitor the efficacy of anti-obesity treatments and/or therapies that target dyslipidemias.

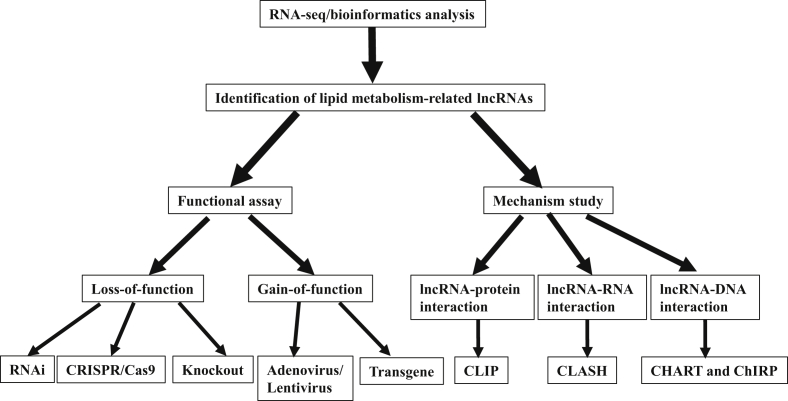

Finally, experimental tools are essential for progress in any of the future directions. As shown in Figure 2, lncRNAs associated with lipid metabolism could be further identified through RNA-seq and bioinformatics analysis. For functional assays of these identified lncRNAs, both loss- and gain-of-function assays can be performed in cultured cells [23], [26], [31], mice [23], and monkeys [31]. Traditional RNAi/antisense oligonucleotides [26], [31], knockout [74], and newly developed CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing tools [75] can be used to suppress lncRNA expression, while adenovirus, lentivirus [26], [44], and transgene [76] mediated overexpression of lncRNAs can be used in gain-of-function assays. For mechanistic studies of lncRNAs, it is very important to identify the interacting proteins or nuclei acids (RNA or DNA) by lncRNA-protein (e.g. crosslinking immunoprecipitation, CLIP [77]), lncRNA-RNA (crosslinking analysis of synthetic hybrids, CLASH [78]) or lncRNA-DNA (capture hybridization analysis of RNA targets, CHART [79]; and chromatin isolation by RNA purification, ChIRP [78]) interaction assays. Moreover, this field will be greatly advanced by the development of additional technologies that effectively determine the function and mechanisms of lncRNAs in the regulation of lipid metabolism under normal and obese conditions.

Figure 2.

Workflow for identification, functional assay and mechanistic study of lncRNAs in the regulation of lipid metabolism.

Funding

This study was supported by Changbai Mountain Scholars Program of The People's Government of Jilin Province 2013046 (to Z. C.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 31500957 (to Z. C.), the Jilin Talent Development Foundation 111860000 (to Z. C.), and the startup funds from Northeast Normal University Grant 120401204 (to Z. C.).

Acknowledgments

I thank Dr. David L. Morris (Indiana University School of Medicine) and Dr. Liwei Xie (University of Georgia) for proof reading and editing this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ali A.T., Hochfeld W.E., Myburgh R., Pepper M.S. Adipocyte and adipogenesis. European Journal of Cell Biology. 2013;92:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kersten S. Mechanisms of nutritional and hormonal regulation of lipogenesis. EMBO Reports. 2001;2:282–286. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duncan R.E., Ahmadian M., Jaworski K., Sarkadi-Nagy E., Sul H.S. Regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes. Annual Review of Nutrition. 2007;27:79–101. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watt M.J., Hoy A.J. Lipid metabolism in skeletal muscle: generation of adaptive and maladaptive intracellular signals for cellular function. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;302:E1315–E1328. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00561.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartelt A., Bruns O.T., Reimer R., Hohenberg H., Ittrich H., Peldschus K. Brown adipose tissue activity controls triglyceride clearance. Nature Medicine. 2011;17:200–205. doi: 10.1038/nm.2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Celi F.S., Le T.N., Ni B. Physiology and relevance of human adaptive thermogenesis response. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2015;26:238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braconi C., Kogure T., Valeri N., Huang N., Nuovo G., Costinean S. microRNA-29 can regulate expression of the long non-coding RNA gene MEG3 in hepatocellular cancer. Oncogene. 2011;30:4750–4756. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kingwell K. Cardiovascular disease: microRNA protects the heart. Nature Review Drug Discovery. 2011;10:98. doi: 10.1038/nrd3380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muhonen P., Holthofer H. Epigenetic and microRNA-mediated regulation in diabetes. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2009;24:1088–1096. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maciotta S., Meregalli M., Torrente Y. The involvement of microRNAs in neurodegenerative diseases. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2013;7:265. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smolle E., Haybaeck J. Non-coding RNAs and lipid metabolism. International Journal of Molecular Science. 2014;15:13494–13513. doi: 10.3390/ijms150813494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lang-Ouellette D., Richard T.G., Morin P., Jr. Mammalian hibernation and regulation of lipid metabolism: a focus on non-coding RNAs. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2014;79:1161–1171. doi: 10.1134/S0006297914110030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Heesch S., van Iterson M., Jacobi J., Boymans S., Essers P.B., de Bruijn E. Extensive localization of long noncoding RNAs to the cytosol and mono- and polyribosomal complexes. Genome Biology. 2014;15:R6. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-1-r6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He Y., Meng X.M., Huang C., Wu B.M., Zhang L., Lv X.W. Long noncoding RNAs: novel insights into hepatocelluar carcinoma. Cancer Letters. 2014;344:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirza A.H., Kaur S., Brorsson C.A., Pociot F. Effects of GWAS-associated genetic variants on lncRNAs within IBD and T1D candidate loci. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105723. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reddy M.A., Chen Z., Park J.T., Wang M., Lanting L., Zhang Q. Regulation of inflammatory phenotype in macrophages by a diabetes-induced long noncoding RNA. Diabetes. 2014;63:4249–4261. doi: 10.2337/db14-0298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu J.Y., Yao J., Li X.M., Song Y.C., Wang X.Q., Li Y.J. Pathogenic role of lncRNA-MALAT1 in endothelial cell dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Cell Death Disease. 2014;5:e1506. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kameswaran V., Kaestner K.H. The missing lnc(RNA) between the pancreatic β-cell and diabetes. Frontiers in Genetics. 2014;5 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao X.Y., Lin J.D. Long noncoding RNAs: a new regulatory code in metabolic control. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2015;40:586–596. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruan X. Long non-coding RNA central of glucose homeostasis. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2015 doi: 10.1002/jcb.25427. n/a-n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellis B.C., Graham L.D., Molloy P.L. CRNDE, a long non-coding RNA responsive to insulin/IGF signaling, regulates genes involved in central metabolism. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2014;1843:372–386. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hung C.L., Wang L.Y., Yu Y.L., Chen H.W., Srivastava S., Petrovics G. A long noncoding RNA connects c-Myc to tumor metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:18697–18702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415669112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li P., Ruan X., Yang L., Kiesewetter K., Zhao Y., Luo H. A liver-enriched long non-coding RNA, lncLSTR, regulates systemic lipid metabolism in mice. Cell Metabolism. 2015;21:455–467. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J., Cui X., Shi C., Chen L., Yang L., Pang L. Differential lncRNA expression profiles in brown and white adipose tissues. Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2015;290:699–707. doi: 10.1007/s00438-014-0954-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei N., Wang Y., Xu R.X., Wang G.Q., Xiong Y., Yu T.Y. PU.1 antisense lncRNA against its mRNA translation promotes adipogenesis in porcine preadipocytes. Animal Genetics. 2015;46:133–140. doi: 10.1111/age.12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao X.Y., Li S., Wang G.X., Yu Q., Lin J.D. A long noncoding RNA transcriptional regulatory circuit drives thermogenic adipocyte differentiation. Molecular Cell. 2014;55:372–382. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Necsulea A., Soumillon M., Warnefors M., Liechti A., Daish T., Zeller U. The evolution of lncRNA repertoires and expression patterns in tetrapods. Nature. 2014;505:635–640. doi: 10.1038/nature12943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paralkar V.R., Mishra T., Luan J., Yao Y., Kossenkov A.V., Anderson S.M. Lineage and species-specific long noncoding RNAs during erythro-megakaryocytic development. 2014 doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-544494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panzitt K., Tschernatsch M.M., Guelly C., Moustafa T., Stradner M., Strohmaier H.M. Characterization of HULC, a novel gene with striking up-regulation in hepatocellular carcinoma, as noncoding RNA. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:330–342. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cui M., Xiao Z., Wang Y., Zheng M., Song T., Cai X. Long noncoding RNA HULC modulates abnormal lipid metabolism in hepatoma cells through an miR-9-mediated RXRA signaling pathway. Cancer Research. 2015;75:846–857. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halley P., Kadakkuzha B.M., Faghihi M.A., Magistri M., Zeier Z., Khorkova O. Regulation of the apolipoprotein gene cluster by a long noncoding RNA. Cell Reports. 2014;6:222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lai C.Q., Parnell L.D., Ordovas J.M. The APOA1/C3/A4/A5 gene cluster, lipid metabolism and cardiovascular disease risk. Current Opinion in Lipidology. 2005;16:153–166. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000162320.54795.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang L., Lin C., Jin C., Yang J.C., Tanasa B., Li W. lncRNA-dependent mechanisms of androgen-receptor-regulated gene activation programs. Nature. 2013;500:598–602. doi: 10.1038/nature12451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu Y.W., Yang J.Y., Ma X., Chen Z.P., Hu Y.R., Zhao J.Y. A lincRNA-DYNLRB2-2/GPR119/GLP-1R/ABCA1-dependent signal transduction pathway is essential for the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Journal of Lipid Research. 2014;55:681–697. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M044669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alvarez-Dominguez J.R., Bai Z., Xu D., Yuan B., Lo K.A., Yoon M.J. De Novo reconstruction of adipose tissue transcriptomes reveals long non-coding RNA regulators of brown adipocyte development. Cell Metabolism. 2015;21:764–776. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farmer S.R. Transcriptional control of adipocyte formation. Cell Metabolism. 2006;4:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu B., Gerin I., Miao H., Vu-Phan D., Johnson C.N., Xu R. Multiple roles for the non-coding RNA SRA in regulation of adipogenesis and insulin sensitivity. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu S., Xu R., Gerin I., Cawthorn W.P., Macdougald O.A., Chen X.W. SRA regulates adipogenesis by modulating p38/JNK phosphorylation and stimulating insulin receptor gene expression and downstream signaling. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu S., Sheng L., Miao H., Saunders T.L., MacDougald O.A., Koenig R.J. SRA gene knockout protects against diet-induced obesity and improves glucose tolerance. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2014;289:13000–13009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.564658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun L., Goff L.A., Trapnell C., Alexander R., Lo K.A., Hacisuleyman E. Long noncoding RNAs regulate adipogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:3387–3392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222643110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiao T., Liu L., Li H., Sun Y., Luo H., Li T. Long noncoding RNA ADINR regulates adipogenesis by transcriptionally activating C/EBPalpha. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;5:856–865. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cooper D.R., Carter G., Li P., Patel R., Watson J.E., Patel N.A. Long non-coding RNA NEAT1 associates with SRp40 to temporally regulate PPARgamma2 splicing during adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells. Genes (Basel) 2014;5:1050–1063. doi: 10.3390/genes5041050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gernapudi R., Wolfson B., Zhang Y., Yao Y., Yang P., Asahara H. miR-140 promotes expression of long non-coding RNA NEAT1 in adipogenesis. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2015 doi: 10.1128/MCB.00702-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Divoux A., Karastergiou K., Xie H., Guo W., Perera R.J., Fried S.K. Identification of a novel lncRNA in gluteal adipose tissue and evidence for its positive effect on preadipocyte differentiation. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22:1781–1785. doi: 10.1002/oby.20793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.You L.H., Zhu L.J., Yang L., Shi C.M., Pang L.X., Zhang J. Transcriptome analysis reveals the potential contribution of long noncoding RNAs to brown adipocyte differentiation. Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00438-015-1026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang J., Cui X., Shen Y., Pang L., Zhang A., Fu Z. Distinct expression profiles of LncRNAs between brown adipose tissue and skeletal muscle. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2014;443:1028–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.12.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gathercole L.L., Morgan S.A., Bujalska I.J., Hauton D., Stewart P.M., Tomlinson J.W. Regulation of lipogenesis by glucocorticoids and insulin in human adipose tissue. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel V.J., Joharapurkar A.A., Shah G.B., Jain M.R. Effect of GLP-1 based therapies on diabetic dyslipidemia. Current Diabetes Review. 2014;10:238–250. doi: 10.2174/1573399810666140707092506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mullur R., Liu Y.-Y., Brent G.A. Thyroid hormone regulation of metabolism. 2014 doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Q., Yuan B., Lo K.A., Patterson H.C., Sun Y., Lodish H.F. Adiponectin regulates expression of hepatic genes critical for glucose and lipid metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:14568–14573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211611109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hynes G.R., Jones P.J. Leptin and its role in lipid metabolism. Current Opinion in Lipidology. 2001;12:321–327. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200106000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reidy S.P., Weber J.-M. Leptin: an essential regulator of lipid metabolism. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 2000;125:285–298. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(00)00159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Horton J.D., Goldstein J.L., Brown M.S. SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;109:1125–1131. doi: 10.1172/JCI15593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Filhoulaud G., Guilmeau S., Dentin R., Girard J., Postic C. Novel insights into ChREBP regulation and function. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2013;24:257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dentin R., Denechaud P.-D., Benhamed F., Girard J., Postic C. Hepatic gene regulation by glucose and polyunsaturated fatty acids: a role for ChREBP. The Journal of Nutrition. 2006;136:1145–1149. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.5.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kalaany N.Y., Mangelsdorf D.J. LXRS and FXR: the yin and yang of cholesterol and fat metabolism. Annual Review of Physiology. 2006;68:159–191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.033104.152158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Niesor E.J., Flach J., Lopes-Antoni I., Perez A., Bentzen C.L. The nuclear receptors FXR and LXRalpha: potential targets for the development of drugs affecting lipid metabolism and neoplastic diseases. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2001;7:231–259. doi: 10.2174/1381612013398185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chawla A., Barak Y., Nagy L., Liao D., Tontonoz P., Evans R.M. PPAR-gamma dependent and independent effects on macrophage-gene expression in lipid metabolism and inflammation. Nature Medicine. 2001;7:48–52. doi: 10.1038/83336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Medina-Gomez G., Gray S.L., Yetukuri L., Shimomura K., Virtue S., Campbell M. PPAR gamma 2 prevents lipotoxicity by controlling adipose tissue expandability and peripheral lipid metabolism. PLoS Genetics. 2007;3:e64. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bajaj M., Suraamornkul S., Hardies L.J., Glass L., Musi N., DeFronzo R.A. Effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-alpha and PPAR-gamma agonists on glucose and lipid metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1723–1731. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0698-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martin P.G.P., Guillou H., Lasserre F., Déjean S., Lan A., Pascussi J.-M. Novel aspects of PPARα-mediated regulation of lipid and xenobiotic metabolism revealed through a nutrigenomic study. Hepatology. 2007;45:767–777. doi: 10.1002/hep.21510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang L., Ding Y., Chen Y., Zhang S., Huo C., Wang Y. The proteomics of lipid droplets: structure, dynamics, and functions of the organelle conserved from bacteria to humans. Journal of Lipid Research. 2012;53:1245–1253. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R024117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Olofsson S.O., Andersson L., Haversen L., Olsson C., Myhre S., Rutberg M. The formation of lipid droplets: possible role in the development of insulin resistance/type 2 diabetes. Prostaglandins Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids. 2011;85:215–218. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barbosa A.D., Savage D.B., Siniossoglou S. Lipid droplet–organelle interactions: emerging roles in lipid metabolism. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2015;35:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Andrews S.J., Rothnagel J.A. Emerging evidence for functional peptides encoded by short open reading frames. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2014;15:193–204. doi: 10.1038/nrg3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruiz-Orera J., Messeguer X., Subirana J.A., Alba M.M. Long non-coding RNAs as a source of new peptides. Elife. 2014;3:e03523. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lu J., Wu X., Hong M., Tobias P., Han J. A potential suppressive effect of natural antisense IL-1β RNA on lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-1β expression. The Journal of Immunology. 2013;190:6570–6578. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou X., Yin C., Dang Y., Ye F., Zhang G. Identification of the long non-coding RNA H19 in plasma as a novel biomarker for diagnosis of gastric cancer. Scientific Reports. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep11516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tong Y.S., Wang X.W., Zhou X.L., Liu Z.H., Yang T.X., Shi W.H. Identification of the long non-coding RNA POU3F3 in plasma as a novel biomarker for diagnosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Molecular Cancer. 2015;14:3. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-14-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li D., Chen G., Yang J., Fan X., Gong Y., Xu G. Transcriptome analysis reveals distinct patterns of long noncoding RNAs in heart and plasma of mice with heart failure. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lorenzen J.M., Schauerte C., Kielstein J.T., Hübner A., Martino F., Fiedler J. Circulating long noncoding RNA TapSAKI is a predictor of mortality in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Clinical Chemistry. 2015;61:191–201. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.230359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bala S., Csak T., Momen-Heravi F., Lippai D., Kodys K., Catalano D. Biodistribution and function of extracellular miRNA-155 in mice. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:10721. doi: 10.1038/srep10721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang Z., Deng Z., Dahmane N., Tsai K., Wang P., Williams D.R. Telomeric repeat-containing RNA (TERRA) constitutes a nucleoprotein component of extracellular inflammatory exosomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:E6293–E6300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505962112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sauvageau M., Goff L.A., Lodato S., Bonev B., Groff A.F., Gerhardinger C. Multiple knockout mouse models reveal lincRNAs are required for life and brain development. eLife. 2013;2:e01749. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Han J., Zhang J., Chen L., Shen B., Zhou J., Hu B. Efficient in vivo deletion of a large imprinted lncRNA by CRISPR/Cas9. RNA Biology. 2014;11:829–835. doi: 10.4161/rna.29624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guo G., Kang Q., Zhu X., Chen Q., Wang X., Chen Y. A long noncoding RNA critically regulates Bcr-Abl-mediated cellular transformation by acting as a competitive endogenous RNA. Oncogene. 2015;34:1768–1779. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Huppertz I., Attig J., D’Ambrogio A., Easton L.E., Sibley C.R., Sugimoto Y. iCLIP: protein–RNA interactions at nucleotide resolution. Methods. 2014;65:274–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chu C., Spitale R.C., Chang H.Y. Technologies to probe functions and mechanisms of long noncoding RNAs. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2015;22:29–35. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Simon M.D., Wang C.I., Kharchenko P.V., West J.A., Chapman B.A., Alekseyenko A.A. The genomic binding sites of a noncoding RNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:20497–20502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113536108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]