Abstract

Glucocorticoids exert a wide range of physiological effects, including the induction of apoptosis in lymphocytes. The progression of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis is a multi-component process requiring contributions from both genomic and cytoplasmic signaling events. There is significant evidence indicating that the transactivation activity of the glucocorticoid receptor is required for the initiation of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. However, the rapid cytoplasmic effects of glucocorticoids may also contribute to the glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis-signaling pathway. Endogenous glucocorticoids shape the T-cell repertoire through both the induction of apoptosis by neglect during thymocyte maturation and the antagonism of T-cell receptor (TCR)-induced apoptosis during positive selection. Owing to their ability to induce apoptosis in lymphocytes, synthetic glucocorticoids are widely used in the treatment of haematological malignancies. Glucocorticoid chemotherapy is limited, however, by the emergence of glucocorticoid resistance. The development of novel therapies designed to overcome glucocorticoid resistance will dramatically improve the efficacy of glucocorticoid therapy in the treatment of haematological malignancies.

Keywords: glucocorticoid, apoptosis, lymphocyte, haematological malignancy, glucocorticoid resistance

Introduction

Glucocorticoids are a class of essential stress-induced steroid hormones regulating a variety of cardiovascular, metabolic, homeostatic and immunological functions. Endogenous glucocorticoids are synthesized and secreted under the control of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in response to stressors including environmental stress, nociception and emotion. Stimulation of hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) secretion prompts the release of adreno-corticototropic hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary, which induces glucocorticoid synthesis within the zona fasiculata of the adrenal cortex. Glucocorticoids auto-regulate their secretion though negative feedback inhibition of CRH and ACTH synthesis and release. In humans, cortisol is the predominant circulating glucocorticoid. Once in circulation, natural glucocorticoids are predominately bound to corticosteroid-binding globulin (CBG). Due to their lipophilic nature, endogenous glucocorticoids are widely bioavailable and easily cross the cell membrane via passive diffusion (Hermoso and Cidlowski, 2003; Rhen and Cidlowski, 2005).

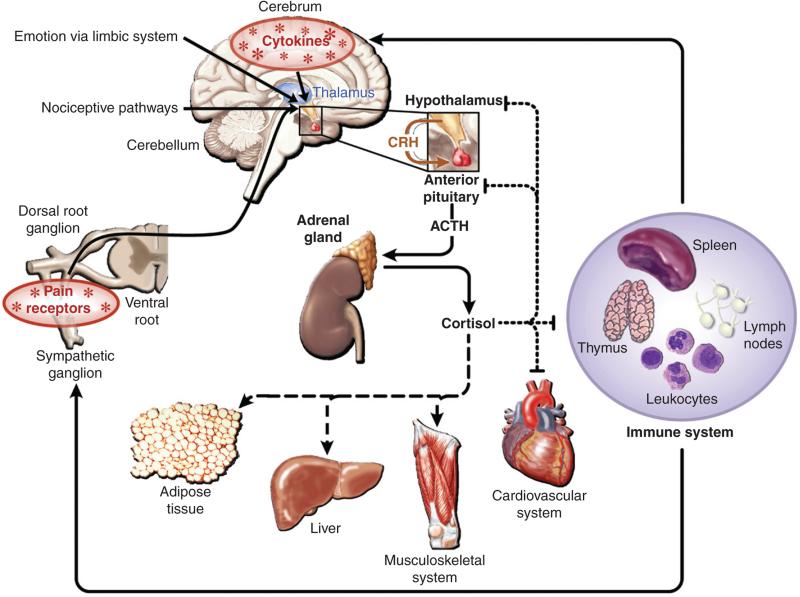

Glucocorticoids exert their physiological effects through the ubiquitously expressed glucocorticoid receptor (GR), a member of the nuclear hormone receptor super family of ligand-activated transcription factors. Upon ligand binding, the GR translocates to the nucleus where it activates or represses the transcription of glucocorticoid-responsive genes. Due to the broad distribution of both glucocorticoids and their cognate receptors, glucocorticoid signaling exerts a wide range of physiological actions. For example, in the liver and adipose tissue, glucocorticoids positively regulate metabolism through the stimulation of gluconogenesis and lipolysis, respectively. Conversely, in the immune compartment, glucocorticoids are largely inhibitory, causing immune suppression through the induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest and the inhibition of inflammation via the repression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 1) (Hermoso and Cidlowski, 2003; Rhen and Cidlowski, 2005).

Fig. 1.

Pleitrophic effects of glucocorticoids in responsive tissues. Endogenous glucocorticoids are generated in response to various stressors, including emotion and nociception. The subsequent physiolgical actions of glucocorticoids in responsive tissues are denoted as stimulatory (dashed line) or inhibitory (dotted line); (adapted from Rhen and Cidlowski, 2005).

Given their broad bioavailability and diverse physiological effects, synthetic glucocorticoids are among the most commonly prescribed drugs for the treatment of inflammatory disorders, autoimmune diseases and sepsis. They are also a mainstay in the treatment of haematological malignancies. Numerous high-affinity synthetic glucocorticoids are clinically available, including prednisone and dexamethasone. However, prolonged use of these compounds is complicated by numerous deleterious side effects such as osteoporosis, hypertension, psychosis, Cushing's syndrome and leucopenia (Rhen and Cidlowski, 2005). Glucocorticoid use in chemotherapy is limited by the development of glucocorticoid resistance. Glucocorticoid resistance in leukemia and lymphoma is correlated with a poor prognosis (Dordelmann et al., 1999; Irving et al., 2005; Riml et al., 2004; Schmidt et al., 2004). The mechanisms governing glucocorticoid resistance in these malignancies are an area of considerable interest to both the scientific and medical communities. This chapter will address the role of glucocorticoids in the induction of apoptosis of healthy and malignant lymphocytes as well as the molecular determinants of glucocorticoid resistance in haematological malignancies.

Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of lymphoid cells

Glucocorticoid receptor

Structure

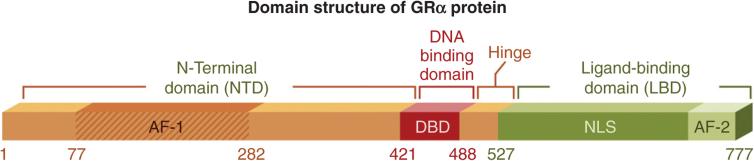

The GR is a member of the type I nuclear hormone receptor super family. Members of this super family are characterized by the formation of homodimers and the presence of three distinct functional domains: the C-terminal ligand-binding domain (LBD), the internal zinc-finger DNA-binding domain (DBD) and the N-terminal transactivation domain (NTD) (Escriva et al., 2004; Escriva et al., 1997; Giguere et al., 1986; Laudet et al., 1992; Weinberger et al., 1985). The GR gene (NR3C1) is located on chromosome 5q31.3 and encodes nine exons (Theriault et al., 1989). Exon 1 represents the 5′-untranslated region while exons 2–9 are protein coding (Duma et al., 2006). Exon 2 encodes the majority of N-terminal domain. This region houses the activating function (AF-1) transactivation domain (amino acids 77–262), which interacts with the basal transcription machinery in order to induce transcription (Wright et al., 1993). The central DBD is encoded by exons 3–4 and mediates receptor binding to glucocorticoid response elements (GREs) within the promoters of responsive genes. The DBD also consists of two conserved zinc fingers, which facilitate interaction with nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and AP-1 transcription factor (first zinc finger) as well as receptor dimerization (second zinc finger) (Heck et al., 1994; Liden et al., 1997; Tao et al., 2001). The region between the two zinc fingers houses a nuclear export signal (NES) (Black et al., 2001; Miesfeld et al., 1987; Tao et al., 2001). A hinge region adjacent to the DBD contains a nuclear localization signal at amino acids 491–498 (Freedman and Yamamoto, 2004). Finally, exons 5–9 encode the C-terminal LBD. This region is responsible for ligand binding and cofactor binding, and also contains a weak AF-2 transactivation domain (Bledsoe et al., 2002; Dahlman-Wright et al., 1992; Hollenberg et al., 1987; Schaaf and Cidlowski, 2002b) (Fig. 2). Following translation, the mature GR resides in the cytosol complexed with an hsp90 dimer, a p23 stabilizing protein and a variety of co-chaperones (Cheung and Smith, 2000; Pratt and Toft, 1997).

Fig. 2.

Domain structure of human glucocorticoid receptor (GR) protein. The GR contains three major functional regions: the N-terminal transactivation domain, the central DNA-binding domain and the C-terminal ligand-binding domain.

Expression

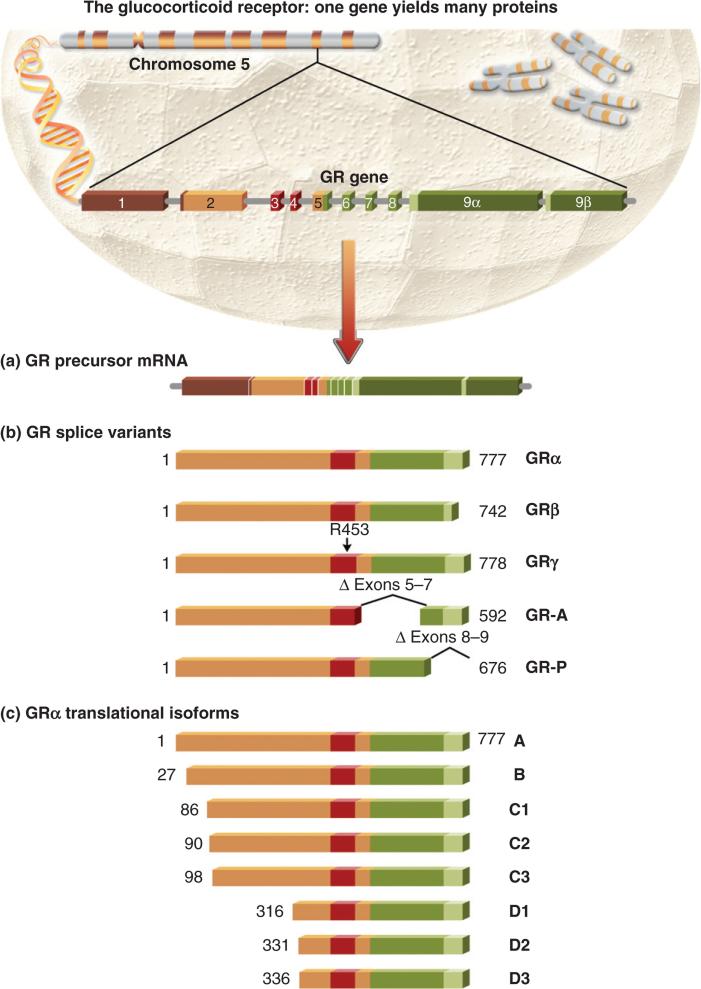

The predominant GR expressed in human tissues is the full-length GRα isoform (Pujols et al., 2002). However, there are numerous additional GR protein isoforms generated from the single GR gene via alternative splicing and the use of alternative translation initiation sites (Fig. 3). Alternative splicing of GR pre-mRNA generates five distinct GR protein isoforms, namely GRα, GRβ, GRγ, GR-A and GR-P. Of these, GRα and GRβ are the most widely expressed. These two receptor isoforms differ in their carboxyl termini due to the use of alternative splicing sites within exon 9 (Hollenberg et al., 1985). GRα is produced from the splicing of exon 8 to the proximal end of exon 9, thus generating a 777-amino acid protein. Exon 9 contributes an additional 50 residues to the LBD of the GRα receptor. GRβ is created from the splicing of exon 8 to the distal end of exon 9, generating a shorter protein of 742 residues, including 15 unique C-terminal residues contributed by exon 9. This splice site is predominantly found in humans and has not been identified in the mouse, explaining the lack of GRβ expression in mice (Otto et al., 1997). The 15 C-terminal residues contributed by exon 9 render GRβ unable to bind glucocorticoids or transactivate glucocorticoid-responsive promoters (Oakley et al., 1999; Yudt et al., 2003). Initially, GRβ was described solely as a dominant negative inhibitor of GRα transactivation (Bamberger et al., 1995; Oakley et al., 1999; 1996). This inhibition occurs through both direct interaction with GRα and competitive recruitment of transcriptional coactivators (de Castro et al., 1996). Deletion of the 15 unique C-terminal amino acids rendered GRβ unable to repress GRα transactivation (Oakley et al., 1996). In contrast to earlier findings, recent studies have described a direct transcriptional role for GRβ. For example, human glucocorticoid receptor β (hGRβ), expressed in the absence of hGRα, possesses intrinsic transcriptional activity. Furthermore, GRβ can selectively bind the GR antagonist RU-486 and this binding diminishes its intrinsic transcriptional activity (Lewis-Tuffin et al., 2007). More recently, Kelly et al. found that GRβ is capable of repressing transcription from the cytokine interleukin (IL)-5 and (IL)-13 promoters via recruitment of histone deactylase I (Kelly et al., 2008).

Fig. 3.

The glucocorticoid receptor (GR): one gene yields many proteins. (a and b) The hGR pre-mRNA undergoes alternative splicing, generating the dominant GRα isoform and the lower abundance GRβ, GRγ, GR-A and GR-P isoforms. (c) The GRα isoform is also subject to alternative translation initiation, giving rise to translational isoforms differing in the length of the N-terminal domain.

The GRγ splice variant harbours an additional three base insertion in the DBD, resulting in the insertion of an arginine residue between the two zinc fingers, thus reducing its transcriptional capacity. The GRγ isoform is largely expressed in lymphocytes (3.8–8.7% of total GR mRNA) (Rivers et al., 1999). However, the evaluation of GRγ protein expression in lymphocytes is hampered by the absence of a specific GRγ antibody. The GR-A splice variant lacks exons 5–7, resulting in a truncated LBD and impaired transactivation activity. Finally, the GR-P splice variant lacks exons 8 and 9, resulting in a truncated LBD lacking the ability to bind glucocorticoids (Moalli et al., 1993).

Additional GR isoforms are generated through the use of alternative translation initiation sites. These isoforms were first identified by immunoblotting as a GRα doublet migrating at 94 and 91 kDa (Lu and Cidlowski, 2005; Yudt and Cidlowski, 2001). The existence of additional GRα isoforms was confirmed by the identification of an in-frame internal translation initiation site at methionine 27. Use of this site is responsible for the generation of the 91-kDa species of GRα, now termed GRα-B (Yudt and Cidlowski, 2001). Further scanning for internal translational start sites revealed the presence of six additional GRα translational isoforms: GRα-C1, C2, C3, D1, D2 and D3 (Lu and Cidlowski, 2005). These isoforms differ only in the length of their N-termini. All bind glucocorticoids with similar affinity, but possess unique gene expression profiles and transcriptional activities. For example, GRα-C3 is the most transcriptionally active, even enhancing the basal transcriptional activity of GRα-A (Lu and Cidlowski, 2005). Conversely, the GRα-D isoform is the least transcriptionally active and unable to induce apoptosis in a stably overexpressing osteosarcoma cell line (Lu et al., 2007). Given the distinct actions of these diverse GR protein isoforms, alterations in their intracellular ratios may influence the lymphoid response to glucocorticoids.

GR expression is under the control of three distinct promoters: 1A, 1B and 1C. Alternative promoter usage results in transcripts bearing exons 1A, 1B and 1C. Alternative splicing of these exons leads to the generation of nine alternative exon 1 splice variants (1A, 1B, 1C, 1D, 1E, 1F, 1H, 1I and 1J) (Breslin et al., 2001; Presul et al., 2007; Turner and Muller, 2005). Further splicing of exons 1A and 1C yields exons 1A1, 1A2 and 1A3 and exons 1C1, 1C2 and 1C3, respectively (Breslin et al., 2001; Turner and Muller, 2005). These assorted transcripts all encode the same protein; however, selective promoter usage may influence downstream splicing and translation initiation events as well as GR protein levels and, ultimately, responsiveness to glucocorticoid treatment (Breslin et al., 2001; Pedersen et al., 2004; Presul et al., 2007; Russcher et al., 2007).

Glucocorticoid receptor signaling

Genomic effects

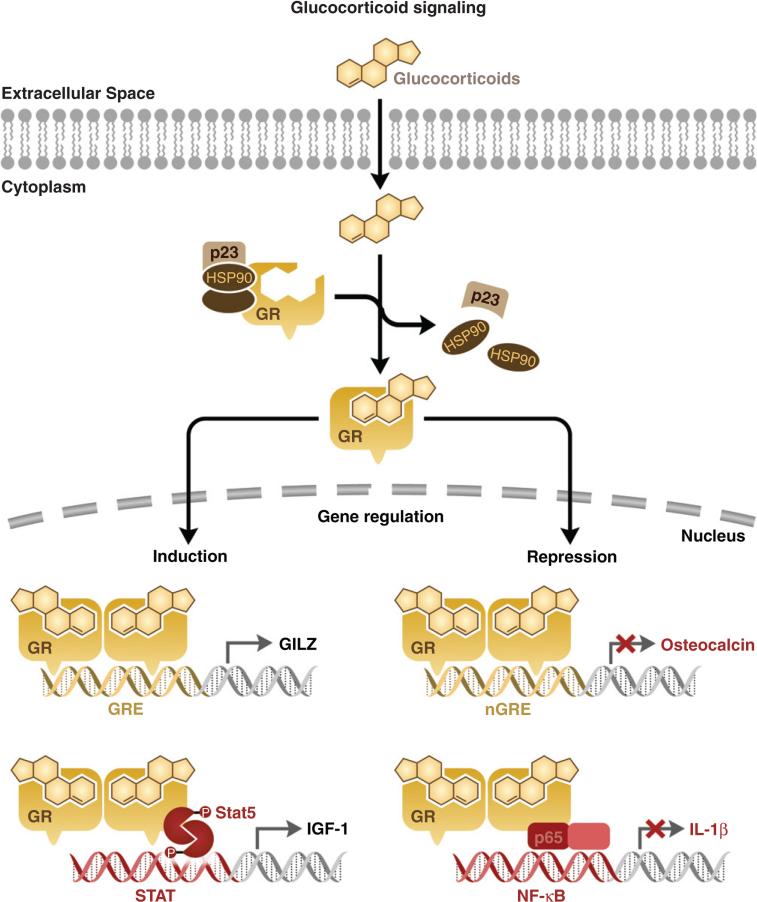

In the cytoplasm, unliganded GR exists as a multi-protein heterocomplex associated with an Hsp90 dimer, a p23 stabilizing protein and various immunophilin chaperone proteins (Cheung and Smith, 2000; Pratt et al., 1996). Upon ligand binding, the GR heterocomplex undergoes a conformational change, releasing the GR from cytoplasmic sequestration, promoting receptor homodimerization and nuclear translocation of the GR homodimer (Davies et al., 2002; Elbi et al., 2004; Freedman and Yamamoto, 2004; Hager et al., 2004; Nagaich et al., 2004). In the nucleus, the activated GR homodimer binds specific DNA elements or GREs within the promoter regions of glucocorticoid-responsive genes. The consensus GRE is composed of two hexamer half-sites separated by three random nucleotides. A majority of GREs contain the hexamer half-site sequence TGTTCT. The number and location of these GREs influences the intensity of the transcriptional response (Freedman and Luisi, 1993). Once bound to the GRE, the GR homodimer recruits transcriptional coactivators as well as the basal transcriptional machinery to the transcription start site. These co-activators include cAMP response element-binding (CREB)-binding protein (CBP), steroid receptor co-activator-1 (SRC-1), GR-interacting protein-1 (GRIP-1), p300 and SWI/SNF (Adcock, 2001; Rogatsky et al., 2002; Wallberg et al., 2000). These co-activators induce histone acetylation, thus allowing for transactivation of glucocorticoid-responsive genes.

The activated GR homodimer is also capable of gene repression. GR can directly interact with DNA via negative GREs within the promoter regions of target genes (Dostert and Heinzel, 2004; Sakai et al., 1988). This interaction inhibits the transcription of genes associated with these promoters. Promoters with described nGREs include the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), osteocalcin and prolactin promoters (Drouin et al., 1993; Malkoski and Dorin, 1999; Meyer et al., 1997). Alternatively, GR can regulate transcription independent of GR binding through direct interaction with other nuclear transcription factors such as NF-κB, AP-1, STAT5 and STAT3, thus modulating the transcription of genes under the control of these transcription factors (Fig. 4) (McKay and Cidlowski, 2000; Ray and Prefontaine, 1994; Scheinman et al., 1995; Stocklin et al., 1996; Yang-Yen et al., 1990; Zhang et al., 1997).

Fig. 4.

Mechanisms of glucocorticoid-regulated gene expression. Ligand binding liberates the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) from cytosolic sequestration, leading to rapid nuclear translocation and homodimerization. In the nucleus, GR can activate gene transcription through direct binding to GREs in the DNA or through stimulatory interactions with transcription factors such as STAT5. GR can also repress gene expression by directly interacting with nGREs in the DNA, or through inhibitory protein–protein interactions with transcription factors including NF-κB.

Cytoplasmic effects

GR signaling has been reported to induce rapid effects in the cytoplasm within minutes of ligand binding. For example, upon ligand binding, Src kinase is released from the cytosolic GR heterocomplex, resulting in lipocortin-1 activation and inhibition of arachidonic acid release. The activation of Src required ligand-bound GR, but was independent of transactivation (Croxtall et al., 2000). Furthermore, glucocorticoids have long been known to alter cytoplasmic ion content, causing rapid alterations in calcium, sodium and potassium concentrations (Bortner et al., 1997; McConkey et al., 1989a, 1989b). Glucocorticoids also cause rapid increases in the mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species, ceramide and hydrogen peroxide, and the lysosomal release of cathepsin B (Cifone et al., 1999; Tonomura et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2006a; Zamzami et al., 1995). Interestingly, glucocorticoids have been reported to induce the translocation of GR to the mitochondria in both thymocytes and lymphoma cells (Sionov et al., 2006). This mitochondrial GR may mediate mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species and ceramide as well as the rapid calcium mobilization following glucocorticoid treatment (Gavrilova-Jordan and Price, 2007).

Recently, membrane-bound GR (mGR) has been suggested in T lymphocytes. Glucocorticoid treatment inhibits TCR signaling via the mGR. This inhibition occurs through the disruption of the lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinases Lck and Fyn. These kinases, anchored to Hsp90, are components of the TCR-linked mGR–multi-protein complex. Glucocorticoid treatment results in the rapid dissociation of Lck and Fyn from the multi-protein complex, leading to reduced phosphorylation of Lck/Fyn substrates and impaired initiation of TCR signaling. This diminished TCR signaling suppresses downstream cytokine synthesis, cellular migration and proliferation of T-lymphocytes (Lowenberg et al., 2005, 2006).

Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis

Genomic signaling

The progression of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis is a multi-faceted process requiring contributions from both genomic and cytoplasmic signaling events. Genomic events alter the protein content of the cell, creating an environment favorable to the execution of the apoptotic pathway. There is significant evidence indicating that the transactivation activity of the GR is required for the initiation of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. For example, glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of lymphocytes does not progress in the presence of actinomycin D or cycloheximide, indicating a requirement for de novo transcription and translation in the execution of the apoptotic cascade (Cifone et al., 1999; Mann and Cidlowski, 2001; Mann et al., 2000; McConkey et al., 1989b; Wang et al., 2006b). The finding that an activation-deficient GR mutant possessing unaltered transrepression capability fails to initiate glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis further supports this observation (Ramdas and Harmon, 1998). Finally, thymocytes isolated from a knock-in mouse harbouring a point mutation presumably preventing receptor dimerization, and thus GR transactivation, also failed to undergo glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis (Reichardt et al., 1998).

Numerous laboratories have performed genome-wide microarray analysis in order to identify genes differentially regulated during glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis (Medh et al., 2003; Schmidt et al., 2006; Thompson and Johnson, 2003; Thompson et al., 2004; Tissing et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2003a; Yoshida et al., 2002). However, to date, only a few genes have been assigned a functional role in the regulation of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. Most notably, the expression of the pro-apoptotic BH3-only Bcl-2 family member Bim is induced by glucocorticoid treatment in murine lymphoma cell lines, human leukemic cell lines, mouse primary thymocytes and human primary chronic lymphoblastic leukemia (CLL) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) samples (Distelhorst, 2002; Iglesias-Serret et al., 2007; Schmidt et al., 2004, 2006; Wang et al., 2003a). The mechanism of induction is likely indirect, as there is no GRE in the promoter region of the Bim gene (Bouillet et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2003a). One potential mechanism of Bim induction is via the induction of the Fox03A/FKHRL1 transcription factor, which is up-regulated by glucocorticoids (Dijkers et al., 2000; Planey et al., 2003). A more recent study found that the activity of the serine/threonine kinase GSK3 is a key mediator of glucocorticoid-induced Bim up-regulation (Nuutinen et al., 2009). The induction and activation of Bim leads to downstream activation of the apoptotic mediators Bax and Bak (Kim et al., 2009). Once activated, these mediators mediate the destabilization of the mitochondrial membrane potential, a hallmark of the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptosis pathway (Kim et al., 2009). The up-regulation of Bim is likely an important mediator of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. For example, thymocytes from homozygous Bim knock-out mice exhibit decreased sensitivity to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis (Bouillet et al., 1999). Furthermore, in vitro studies utilising shRNA or siRNA targeting the various Bim transcripts confirm a substantial role for Bim induction in the progression of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis (Abrams et al., 2004; Lu et al., 2006; Ploner et al., 2008).

The role of glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ) is an area of expanding interest in the study of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. GILZ was first identified as a glucocorticoid-responsive gene by a systemic screen for genes responsive to glucocorticoids in the thymus (D'Adamio et al., 1997). Due to the presence of three GREs in the GILZ promoter, the glucocorticoid induction of GILZ expression is direct and robust (Wang et al., 2004). The strongest evidence that GILZ may mediate glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis is provided by studies of GILZ transgenic mice. In these mice, the GILZ transgene is specifically targeted to the T-cell compartment. Primary thymocytes from these mice were resistant to TCR-induced apoptosis. However, they exhibited augmented glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis due to reduced expression of the Bcl-2 family member, Bcl-XL, as well as increased activation of caspases 8 and 3 (Delfino et al., 2004). GILZ also mediates glucocorticoid-induced cell cycle arrest through direct interaction with and inhibition of the proliferative Ras and Raf oncogenes (Ayroldi et al., 2007).

In addition to Bim and GILZ, glucocorticoids rapidly transactivate the stress gene dexamethasone-induced gene 2 (Dig2) in murine lymphoma cell lines. Interestingly, Dig2 overexpression reduced the sensitivity of these cells to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis, suggesting a pro-survival function for this gene (Wang et al., 2003b). Granzyme A is up-regulated following glucocorticoid treatment in B-ALL cells. Pharmacological inhibition of granzyme A blunted the apoptotic response, indicating that this enzyme is an effector of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis (Yamada et al., 2003). T-cell death-associated gene (TDAG8) is rapidly induced by glucocorticoids in thymocytes. Thymocytes from TDAG8 transgenic mice exhibited increased activation of caspases 3, 8 and 9 following glucocorticoid exposure (Tosa et al., 2003). However, thymocytes from TDAG8-deficient mice remained sensitive to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis, suggesting a minor role for TDAG8 in glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis (Radu et al., 2006). Glucocorticoid exposure represses the pro-survival oncogene c-myc in human leukemic CEM cells (Wang et al., 2003a). Furthermore, glucocorticoids repress the glycolytic hexokinase II enzyme (Tonko et al., 2001). Hexokinase II acts as a stabilizer of the mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC). Interestingly, hexokinase II overexpression abrogated glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis via inhibition of mitochondrial destabilization (Sade et al., 2004). In summary, glucocorticoids regulate the transcription of several genes, the expression of which influences cellular progression through the glucocorticoid-induced apoptotic pathway.

Cytoplasmic signaling

Glucocorticoids cause rapid and sustained increases in cytosolic calcium concentrations in thymocytes, lymphoma cells and B lymphoblasts (Bian et al., 1997; Distelhorst and Dubyak, 1998; Hughes et al., 1997; Lam et al., 1993; McConkey et al., 1989b; Orrenius et al., 1991). Buffering of cytosolic calcium or culture in calcium-free media prevented glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of primary thymocytes (McConkey et al., 1989b). Interestingly, pharmacological inhibition of the calcium-binding protein calmodulin inhibited DNA fragmentation without interfering with cytosolic calcium increase, indicating that calmodulin mediates the downstream apoptotic effect of glucocorticoid-induced calcium mobilization (Dowd et al., 1991). However, the precise role of calcium mobilization in glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis remains controversial. A subsequent study reported that chelation of intracellular calcium inhibits DNA fragmentation, but not glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in primary thymocytes (Iseki et al., 1993). Thus, calcium mobilization is likely required for endonuclease activation, but not other aspects of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis.

Glucocorticoids also cause a net potassium efflux in thymocytes and CEM T-ALL cells (Benson et al., 1996; Bortner and Cidlowski, 2000). This potassium loss enhances apoptosis in thymocytes and normal intracellular potassium levels inhibit DNA fragmentation and caspase-3 activation in lymphocytes (Bortner et al., 1997; Hughes et al., 1997). Furthermore, pharmacological inhibition of plasma membrane potassium channels in primary thymocytes effectively inhibited glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis through the prevention of cytosolic potassium loss and inhibition of mitochondrial membrane destabilization (Dallaporta et al., 1999).

Glucocorticoids (ranging from 10–7 to 10–12 M) induce a rapid increase in intracellular ceramide concentrations in primary thymocytes within 15 min of treatment (Cifone et al., 1999). This increase is receptor dependent, as determined through co-treatment with the GR antagonist RU-486 (Cifone et al., 1999). Furthermore, pharmacological inhibition of ceramide biosynthesis prevented apoptosis in glucocorticoid-treated thymocytes (Cifone et al., 1999). The generation of reactive oxygen species is also dramatically increased in response to glucocorticoids (Zamzami et al., 1995). This increase accompanies a decrease in the mRNA levels of anti-oxidant enzymes and contributes to glucocorticoid-induced cell death (Baker et al., 1996). Furthermore, co-treatment with an exogenous thiol anti-oxidant inhibits glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis (Tonomura et al., 2003). Moreover, in the absence of oxygen, cell death is prevented, indicating that the generation of reactive oxygen species is an important step in the progression of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis (Torres-Roca et al., 2000). Finally, glucocorticoids induce a rapid translocation of GR to the mitochondria in glucocorticoid-sensitive cells (Sionov et al., 2006). Overexpression of a GR species specifically targeted to the mitochondria is sufficient to induce apoptosis, perhaps through the mediation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and ceramide production as well as the rapid calcium mobilization following glucocorticoid exposure (Sionov et al., 2006). These rapid cytoplasmic effects are likely participants in the complex, multi-component glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis-signaling pathway.

Execution of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis

The glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis pathway culminates in the activation of the caspase cascade. Caspases are a family of proteases that cleave substrates at aspartate residues, mediating the dramatic morphological and biochemical changes occurring during apoptosis (Thornberry and Lazebnik, 1998). Studies utilising broad caspase inhibitors have found that glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis requires caspase activation (Bellosillo et al., 1997; Hughes and Cidlowski, 1998; Sarin et al., 1996; Weimann et al., 1999). Caspase activation occurs through two broadly conserved pathways: the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways. In the extrinsic pathway, ligands such as Fas or tumor necrosis factor (TNF) bind cognate receptors on the cell surface, initiating the caspase cascade via activation of caspase 8 (Ashkenazi and Dixit, 1998). The second pathway, the intrinsic or mitochondrial-mediated pathway, involves disruption of the mitochondrial membrane by the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members Bim, Bax and Bak, leading to the release of cytochrome c and apoptotic peptidase-activating factor 1 (Apaf-1) and subsequent activation of caspase 9 (Saleh et al., 1999). Both pathways culminate in the activation of downstream of effector caspases (caspases 3, 7 and 6) (Green, 2000).

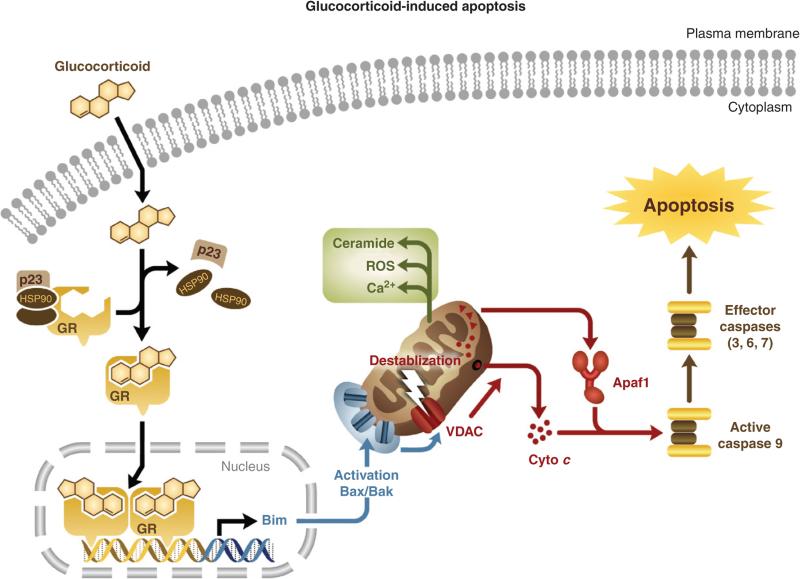

There is evidence suggesting that glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis proceeds via the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway. For example, thymocytes from Apaf-1 and caspase 9 deficient mice exhibit reduced sensitivity to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis (Hakem et al., 1998; Kuida et al., 1998; Yoshida et al., 1998). Therefore, in a simplified model of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis, glucocorticoid exposure leads to the regulation of genes involved in the initiation of apoptosis, namely the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member, Bim. Bim transactivation leads to the activation of downstream apoptotic mediators, Bax and Bak. Upon activation, Bax and Bak mediate the disruption of the mitochondrial membrane potential and the subsequent release of Apaf-1 and cytochrome c into the cytosol. The mitochondria is also responsible for some of the rapid, glucocorticoid-mediated cytoplasmic effects including calcium mobilization and the production of reactive oxygen species and ceramide, all of which may contribute to the progression of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. Apaf-1 and cytochrome c release leads to the activation of caspase 9, the subsequent activation of downstream effector caspases and the execution of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis signaling cascade. In this abbreviated model, glucocorticoids regulate the expression of apoptosis-effector genes, namely the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member, Bim. Bim transactivation leads to the activation of downstream apoptotic mediators, Bax and Bak. Upon activation, Bax and Bak mediate disruption of the mitochondrial membrane potential and the subsequent release of cytochrome c and Apaf-1 into the cytosol. Apaf-1 and cytochrome c release leads to the activation of caspase 9, the subsequent activation of downstream effector caspases and the execution of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. The mitochondria is also responsible for some of the rapid, glucocorticoid-mediated cytoplasmic effects including calcium mobilization and the production of reactive oxygen species and ceramide, all of which may contribute to the progression of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis.

Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of healthy lymphocytes

In the highly coordinated process of T-lymphocyte development, bone marrow progenitors migrate to the thymus where they undergo a transition to double negative (CD4–8–) immature thymocytes (Radtke et al., 2004). Following random rearrangement of the TCR α and β genes, cells become double positive (CD4+8+) and undergo selection based on the specificity of the TCR for self-peptides bound to major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-encoded molecules (Kisielow and von Boehmer, 1995). Double positive thymocytes with TCRs bearing low avidity for self-antigen/MHC undergo ‘death by neglect’. Thymocytes with TCRs bearing high avidity for self-antigen/MHC undergo TCR activation-induced apoptosis (negative selection). Only cells bearing TCRs with intermediate avidity for self-antigen/MHC are rescued from the neglect or negative selection cell death programmes. These cells undergo positive selection, becoming either CD4+ or CD8+ cells. Upon maturation, single positive T cells enter the periphery (Huesmann et al., 1991).

How the TCR induces cell death during neglect and negative selection while simultaneously rescuing cells from cell death during positive selection is an area of considerable research. A role for systemic glucocorticoids in the regulation of thymocyte development was first suggested in 1924, when it was demonstrated that bilateral adrenalectomy leads to thymic hypertrophy (Jaffe, 1924). It has been proposed that glucocorticoids interact with TCR signaling in a relationship termed ‘mutual antagonism’. The first evidence in support of the mutual antagonism model reported that stimulation of the TCR protected T cells from glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. Conversely, glucocorticoids prevented TCR activation-induced cell death in the same model system, thus coining the phrase ‘mutual antagonism’ (Iwata et al., 1991; Zacharchuk et al., 1990). In this model, glucocorticoids are key modulators of the ‘death by neglect’ of low avidity TCR-bearing thymocytes (Zilberman et al., 1996, 2004). In addition, glucocorticoids interfere with the TCR-induced death signaling in cells with intermediate avidity TCRs, allowing these cells to escape TCR-induced apoptosis and undergo positive selection (Iwata et al., 1991; Zacharchuk et al., 1990). However, the TCR activation-induced apoptotic signaling in double positive thymocytes bearing high avidity TCRs overwhelms glucocorticoid antagonism, allowing for the deletion of these cells during negative selection (Ashwell et al., 2000).

TCR signaling activates extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) signaling (Tsitoura and Rothman, 2004). ERK is responsible for rapid phosphorylation and inactivation of Bim, a key modulator of the glucocorticoid-induced apoptotic pathway (Ley et al., 2003). Therefore, TCR may antagonize glucocorticoid signaling via ERK activation and Bim inactivation. Alternatively, glucocorticoid signaling results in the rapid dissociation of the lymphocyte-specific kinases LCK and FYN from the TCR complex, thus inactivating TCR signaling (Lowenberg et al., 2006). Therefore, one potential mechanism of glucocorticoid antagonism of TCR is through disruption of the TCR complex. In summary, in this model of mutual antagonism, glucocorticoids act as a rheostat, modulating the threshold for TCR activation-induced apoptosis during thymocyte selection.

In vitro evidence for the mutual antagonism model was generated by experiments in fetal thymic organ culture (FTOC). Pharmacological inhibition of glucocorticoid production or glucocorticoid signaling sensitized cells to TCR-induced apoptosis, ultimately altering the T-cell repertoire (Vacchio et al., 1998, 1994). Furthermore, in vivo knock-down of GR in the T-cell compartment dramatically reduced thymus size due to a decrease in the number of double positive and single positive thymocytes. Thus, the absence of glucocorticoid signaling in vivo sensitized double positive thymocytes to negative selection (King et al., 1995). However, more recent studies of T-cell specific GR knock-out mice detected no abnormality in thymocyte development (Baumann et al., 2005; Brewer et al., 2003). Conversely, additional studies modulating GR expression in the thymus report dramatic alterations in thymic cellularity and thymocyte maturation (Jondal et al., 2004; King et al., 1995; Pazirandeh et al., 2002). Therefore, the precise role of glucocorticoids in thymocyte development remains controversial.

Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of haematological malignancies

The therapeutic potential of synthetic glucocorticoids for the treatment of haematological malignancies was first suggested in 1943, when the administration of hydroxycorticosterone resulted in apoptosis of malignant lymphocytes in the mouse (Dougherty and White, 1943; Heilman FR, 1944). Subsequently, synthetic glucocorticoids were implemented in the clinical treatment of leukemia and lymphoblastomas (Pearson, 1949; Stickney, 1950). Today, glucocorticoids are central in the treatment of haematological malignancies and are utilized as adjuvants in a majority of chemotherapeutic regimens. Chemotherapy of haematological malignancies consists of three phases: induction of remission, intensification (or consolidation) and maintenance of remission. The induction phase involves the rapid destruction of malignant cells in order to achieve remission. Remission is defined as the presence of fewer than 5% malignant cells in the bone marrow and periphery. The intensification phase utilizes chemotherapy to further reduce tumor burden and may consist of bone marrow stem cell transplantation. Finally, maintenance of remission utilizes combination therapies to maintain remission and prevent relapse (Hoffbrand et al., 2001). This section will review the efficacy and limitations of synthetic glucocorticoids in the treatment of individual haematomalignancies.

Glucocorticoid therapy of acute lymphoblastic leukemia

ALL is characterized as an accumulation of bone marrow-derived malignant, immature lymphocytes. ALL is predominantly a disease of children and adolescents, with this age group comprising two-thirds of the 4000 cases diagnosed annually in the United States (Pui and Evans, 1998). Historically, the use of prednisone monotherapy in the induction phase was efficacious, resulting in remission of 45–65% of the primary childhood ALL cases reported (Hyman et al., 1959). Today, prednisone is widely used in conjunction with the alkylating agent vincristin, the topoisomerase II inhibitor anthracycline and catalytic asparaginase in the induction phase of ALL chemotherapy. This combination regimen induces complete remission in 98% of children and 85% of adults (Pui and Evans, 2006). Following the induction of remission, prednisone is commonly utilized in the maintenance therapy of ALL (Gokbuget and Hoelzer, 2006). The response to prednisone therapy is a strong predictor of prognosis in infant ALL. Infants with a poor response following a 7-day course of prednisone are less responsive to conventional chemotherapy and require more intensive induction therapies (Dordelmann et al., 1999). Furthermore, early response to combined chemotherapy is also a predictor of outcome in childhood ALL (Schrappe et al., 1996). Therefore, the prednisone response in childhood and infant ALL is currently a prognostic factor utilized in the adaptation of chemotherapy treatment protocols.

Glucocorticoid therapy of chronic lymphoblastic leukemia

CLL is characterized as a malignant neoplastic proliferation of the B-cell (common) or T-cell (rare) compartment. CLL is the most commonly diagnosed lymphoproliferative disorder of the Western world (30% of cases) and is primarily an adult disease, with a majority of cases occurring in individuals over 50 (Rozman and Montserrat, 1995). Historically, synthetic glucocorticoids were not added to the conventional chemotherapy regimen of CLL. This exclusion was based on the observations of clinical studies performed in the 1970s and 1980s, which found that the addition of prednisone to the conventional CLL regimen conferred no additional benefit (Pettitt, 2008). However, in the late 1990s an in vitro study of cultured CLL cells from patients with relapsed or resistant disease found that these cells were sensitive to apoptosis induced by high doses of the synthetic glucocorticoid methylprednisolone (Bosanquet et al., 1995). Subsequent clinical trials of high-dose methylprednisolone (HDMP) in CLL patients achieved a response rate of 43% (Bosanquet et al., 1995). Further trials have been performed in CLL patients with primary or relapsed/resistant disease utilizing combination chemotherapy consisting of HDMP and the chimeric monoclonal CD20 antibody, rituximab. This study observed a response rate of 93% for primary CLL and 83% for relapsed/refractory CLL (Castro et al., 2009). The success of HDMP therapy may be due to the fact that glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis is p53 independent. Accordingly, in a separate trial, CLL patients with mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor responded well to HDMP treatment (Thornton et al., 2003). Currently, the use of HDMP in conjunction with conventional chemotherapy or rituximab is gaining popularity in the treatment of CLL.

Glucocorticoid therapy of multiple myeloma

Multiple myeloma (MM) is characterized by an increase of monoclonal plasma cells in the bone marrow, resulting in anaemia, hypercalcaemia and renal failure. MM accounts for 10% of all haematomalignancies (Kyle and Rajkumar, 2008). Use of alkylating agent melphalan in conjunction with the synthetic glucocorticoid prednisone has been the foundation of first-line MM chemotherapy for decades. The overall response rate for this regimen was 50% (Rajkumar et al., 2002). Recently, the FDA approved the use of a more aggressive combination chemotherapy consisting of the anti-angiogenic drug thalidomide and high doses of the synthetic glucocorticoid dexamethasone (Thal/Dex). Randomized trial of this induction regimen resulted in a response rate of 63% (Rajkumar et al., 2006). The Thal/Dex or Thal/Dex/melphalan regimen is currently the most commonly prescribed remission induction regimen for the treatment of MM (Kyle and Rajkumar, 2008). Therefore, synthetic glucocorticoids remain a cornerstone in the chemotherapy of MM.

Glucocorticoid therapy of Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma

Hodgkin's lymphoma, or Hodgkin's disease, is characterized by the orderly spread of malignant lymphocytes through the lymphatic system and the presence of multi-nucleated lymphocytes known as Reed–Sternberg cells (Kuppers et al., 2002). Historically, Hodgkin's disease has been treated with a combination chemotherapy consisting of mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine and prednisone (MOPP), resulting in remission induction of 80% of patients (DeVita et al., 1980). However, the MOPP programme has recently been replaced in favour of more tailoured chemotherapy regimens. These regimens include the Stanford V (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, vincristine, mechlorethamine, etoposide and prednisone) and the BEACOPP (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, procarbazine, etoposide and prednisone), both of which incorporate the synthetic glucocorticoid prednisone (Evens et al., 2008). However, the importance of synthetic glucocorticoids in the remission induction of Hodgkin's disease is unclear as the gold standard chemotherapy regimen, ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine), does not include a synthetic glucocorticoid (Evens et al., 2008). Nevertheless, the Stanford V and BEACOPP regimens represent important glucocorticoid-inclusive treatment alternatives in the chemotherapy of Hodgkin's disease.

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma is comprised of a diverse group of haematomalignancies characterized by the absence of Reed–Sternberg cells. Induction chemotherapies vary depending on the type of lymphoma; however, the first-line chemotherapy regimen in a majority of lymphomas consists of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin and prednisone (CHOP). This combined chemotherapy results in remission induction of 50–60% of primary disease (Fisher et al., 1993). The remaining patients either fail to respond or have relapsed. Recent studies find that these patients may be rescued by a salvage therapy consisting of dexamethasone, etoposide, ifosfamide and cisplatin (DVIP), especially when this therapy is combined with stem cell transplantation (Lazar et al., 2009).

Limitations of glucocorticoid chemotherapy

Given their pleiotrophic physiological effects, the prolonged use of glucocorticoids in chemotherapy is complicated by numerous injurious side effects including muscle wasting, osteoporosis in adults, inhibition of longitudinal bone growth in children and increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections (Rhen and Cidlowski, 2005). These side effects are dose and duration dependent. For example, cancer patients receiving high dose glucocorticoid therapy (more than 400 mg dexamethasone) and prolonged therapy (more than 3 weeks) reported a 76 and 75% incidence of toxicity, respectively (Weissman et al., 1987).

Glucocorticoids promote the degradation of muscle protein to free amino acids, resulting in muscle wasting (Mitch, 2000). In children, glucocorticoids induce apoptosis and inhibit proliferation of chondrocytes, the cells responsible for longitudinal bone growth (Chrysis et al., 2005). In adults, glucocorticoids induce apoptosis of mature osteoblasts and increase the bone resorption activity of osteoclasts, leading to the onset of osteoporosis (Chrysis et al., 2005; Rhen and Cidlowski, 2005). Glucocorticoids are immunosuppressive due to their interference with the NF-κB and AP-1 signaling pathways. These transcription factors are key modulators of the inflammatory response and their repression results in decreased expression of inflammatory mediators including TNFα, IL-1β and numerous inflammatory cytokines (Rhen and Cidlowski, 2005). The glucocorticoid-induced immunosuppression renders patients vulnerable to opportunistic infections such as oral candidiasis, an infection common in patients undergoing long-term glucocorticoid therapy (Walsh and Avashia, 1992).

Another limitation of glucocorticoid chemotherapy is the emergence of glucocorticoid-resistant clonal populations during prolonged glucocorticoid therapy, glucocorticoid resistance upon relapse and the existence of inherently resistant haematomalignancies. Leukemias of the myelogenous lineage are often innately resistant to glucocorticoid therapy (Zwaan et al., 2000). Furthermore, patients with relapsed ALL exhibit increased resistance to glucocorticoid therapy (Schrappe et al., 2000). Glucocorticoid resistance in these cancers is associated with a poor prognosis (Dordelmann et al., 1999; Hongo et al., 1997; Kaspers et al., 1997). Therefore, a more comprehensive understanding of the factors governing glucocorticoid resistance in haematomalignancies may improve the efficacy of glucocorticoid therapy.

Mechanisms of glucocorticoid resistance in haematomalignancies

Altered expression of glucocorticoid receptor isoforms

There is compelling clinical and empirical evidence suggesting that altered expression of GR isoforms contributes to the varied responses of haematomalignancies to glucocorticoid therapy. For example, increased expression of the ‘dominant-negative’ GRβ isoform has been reported in several haematomalignancies. Under normal conditions, GRβ is expressed at extremely low levels (0.16% in healthy lymphocytes) (Honda et al., 2000). However, the levels of GRβ expression are increased in T-ALL CEM cells (0.22%), primary ALL patient samples (0.5–1.2%) and glucocorticoid-resistant CLL (Haarman et al., 2004; Shahidi et al., 1999). Interestingly, the ability of prednisone to induce apoptosis of pediatric ALL cells is inversely correlated with GRβ levels (Koga et al., 2005). Furthermore, human neutrophils exhibit increased GRβ levels and decreased glucocorticoid responsiveness, and the in vitro transfection of mouse neutrophils with GRβ conferred partial glucocorticoid resistance (Strickland et al., 2001). However, the functional significance of increased GRβ expression in haematomalignancies remains controversial, as other studies of GRβ in primary cells from ALL patients have not reported a correlation between GRβ expression and glucocorticoid resistance (Haarman et al., 2004; Tissing et al., 2005a). In the absence of conclusive evidence, the generation of a GRβ transgenic mouse model would be of great value in determining the precise role of GRβ in the development of glucocorticoid resistance.

Altered expression of the additional GR isoforms may also contribute to glucocorticoid resistance. For example, elevated levels of GRγ mRNA are associated with glucocorticoid resistance in a study of primary versus relapsed ALL samples (Haarman et al., 2004). Several studies have identified increased expression of GR-P or GR-A mRNA in glucocorticoid-resistant malignancies (de Lange et al., 2001; Krett et al., 1995; Moalli et al., 1993). However, these findings are contradicted by more recent studies of patient-derived primary ALL cells (Tissing et al., 2005a). Furthermore, altered ratios of GR translational isoform expression may influence glucocorticoid responsiveness. For example, overexpression of the GRα-D isoform, the least transcriptionally active sub-type, confers resistance to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells (Lu et al., 2007). Future studies investigating the complement of various GR translational isoforms in glucocorticoid-resistant patient samples would clarify the role of these variants in the development of glucocorticoid resistance.

Finally, alternative GR promoter usage has been associated with glucocorticoid resistance. For example, exon 1A contains a GRE, which promotes the auto-induction of GR transcription upon glucocorticoid treatment (Geng and Vedeckis, 2004). This auto-induction has been associated with increased responsiveness to glucocorticoid treatment (Purton et al., 2004). Furthermore, cell-type-specific expression of GR promoter transcripts has been reported in a variety of haematomalignant cell lines (Breslin et al., 2001; Geng and Vedeckis, 2004; Nunez and Vedeckis, 2002; Pedersen and Vedeckis, 2003). This variable expression of GR promoter transcripts has been correlated with the diverse responsiveness of haematologic malignancies to glucocorticoid therapy (Breslin et al., 2001; Purton et al., 2004). However, other reports contradict these findings and cite no differences in GR promoter usage or differential induction of various GR promoter transcripts in glucocorticoid-resistant primary ALL cells (Tissing et al., 2006).

Glucocorticoid-induced alterations in GR expression

In lymphoid cells sensitive to glucocorticoids, GR auto-induction in response to steroid treatment is a common observation. This auto-regulatory action can be attributed to the presence of a GRE in the GR promoter region. GR auto-induction has been observed in the glucocorticoid-sensitive CEM T-ALL cell lines, primary ALL cells and immature thymocytes (Barrett et al., 1996; Tissing et al., 2006). Accordingly, the extent of GR auto-induction following glucocorticoid treatment has been directly correlated with the degree of cell death in glucocorticoid-sensitive cells (Geley et al., 1996). However, the importance of GR auto-induction in glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis is challenged by studies of primary ALL xenografts in immune-deficient mice and primary thymocytes. Glucocorticoid-sensitive xenografts contained high levels of basal GR and failed to auto-induce GR upon hormone treatment. Furthermore, glucocorticoid-sensitive primary thymocytes expressing high-basal GR levels also undergo apoptosis in the absence of auto-induction (Oldenburg et al., 1997). These results suggest that in sensitive cells with high basal GR expression, GR auto-induction is not required to induce apoptosis (Bachmann et al., 2007). However, GR auto-induction is essential for apoptosis in cells harbouring low basal levels of GR (Miller et al., 2007; Ramdas et al., 1999; Riml et al., 2004).

Conversely, in cells resistant to glucocorticoids, homologous down-regulation of GR following glucocorticoid treatment is a common observation. For example, in leukemias of myelogenous origin, GR is down-regulated by glucocorticoids, perhaps accounting for their inherent resistance to glucocorticoid therapy (Kfir et al., 2007). Furthermore, homologous GR down-regulation is an indicator of poor prognosis in ALL (Bloomfield et al., 1981; Pui and Costlow, 1986). Therefore, prolonged glucocorticoid therapy, in certain cellular contexts, may result in the emergence of glucocorticoid-resistant cells harbouring low levels of basal GR expression. Homologous down-regulation of GR may employ multiple mechanisms including diminished promoter activity or destabilization of mRNA or protein expression. Homologous down-regulation of GR may be due to decreased activity of the GR promoter. However, use of a heterologous promoter to drive GR expression found that the repressive action of glucocorticoids on GR expression remained intact. Further in vitro studies determined that the region of GR encoded by amino acids 550–697 is essential to the homologous down-regulation of GR (Alksnis et al., 1991; Burnstein et al., 1990, 1994). Additionally, decreased GR mRNA stability may contribute to homologous down-regulation. For example, the presence of AUUUA motifs in the 3′-UTR of GR might be involved in the destabilization of GR mRNA. These motifs are common RNA-binding protein motifs and the action of these RNA binding proteins may contribute to the destabilization of GR mRNA (Chen and Shyu, 1995; Schaaf and Cidlowski, 2002a; Shaw and Kamen, 1986). Finally, homologous down-regulation could be due to decreased GR protein stability. Studies have indicated that the proteosome complex degrades the GR. Pre-treatment of GR overexpressing cells with the proteosomal inhibitor MG-132 impedes homologous down-regulation of GR protein (Wallace and Cidlowski, 2001). Furthermore, GR contains a conserved proline, glutamic acid, serine and threonine (PEST) degradation motif, also contributing to the destabilization of GR protein (Wallace and Cidlowski, 2001). Additionally, non-coding micro-RNAs have recently been identified as negative regulators of gene expression through translational repression of target mRNAs. Hormonal induction of specific microRNAs targeting GR is an attractive model of homologous GR down-regulation. However, microRNAs targeting GR have only been identified in neurons and their function in the regulation of GR mRNA translation in the lymphoid compartment remains unaddressed (Vreugdenhil et al., 2009). The precise role of these proposed mechanisms in the homologous down-regulation of GR observed in glucocorticoid-resistant haematomalignancies remains unclear and additional experiments are warranted. Furthermore, studies of primary ALL xenografts in immune-deficient mice found that the glucocorticoid-resistant tumors possessed sufficient basal levels of GR and did not undergo homologous GR down-regulation upon steroid treatment (Bachmann et al., 2007). These observations suggest that in these neoplasms, glucocorticoid resistance occurs downstream of GR. Clearly, the precise mechanisms governing glucocorticoid resistance in haematomalignancies are divergent and cell-type specific. However, for many haematomalignant cell types, the directionality of GR expression in response to glucocorticoid treatment modulates the efficacy of glucocorticoid therapy.

Mutations in the glucocorticoid receptor

Numerous mutations affecting GRα signaling have been identified in laboratory-derived glucocorticoid-resistant leukemic cell lines. For example, the CEM T-ALL cell line harbours a mutation in the GR LBD (L753F) that hinders GR ligand binding and subsequent transactivation (Hillmann et al., 2000). Accordingly, the T-ALL 6TG1.1 cell line bearing this mutation is resistant to glucocorticoid-induced cell death (Liu et al., 1995; Powers et al., 1993). Additional mutations in the GR LBD, including the G679S, F737L, I559N, V571A, D641V, V729I and I747M also impair the transcriptional activity of GR (Charmandari et al., 2004). Furthermore, a R477H mutation in one allele of the GR gene inhibits DNA binding in glucocorticoid-resistant Jurkat T-ALL cells. This mutation renders the GR unable to transactivate, thus eliminating GR auto-induction and contributing to glucocorticoid resistance in these cells (Riml et al., 2004). However, the majority of studies in patient-derived samples have failed to associate glucocorticoid resistance with mutations in the GR. Mutations in the GR were absent in both glucocorticoid-resistant primary cells derived from ALL patients or glucocorticoid-resistant primary ALL xenografts (Bachmann et al., 2007; Beesley et al., 2009; Tissing et al., 2005b). Therefore, there are key differences in the mechanisms of glucocorticoid resistance in long-term cultured cells and patient-derived samples and the lesions responsible for impaired GR signaling and glucocorticoid resistance in vitro do not contribute to the development of glucocorticoid resistance in vivo.

Aberrant expression of Bcl-2

Aberrant expression of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein is frequently reported in B-cell follicular lymphomas. In these lymphomas, translocation of Bcl-2 places this oncongene adjacent to the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus, resulting in rampant expression of the Bcl-2 fusion gene. This fusion gene is identified in over 80% of B-cell lymphomas and Bcl-2 transgenic mice develop diffuse large-cell lymphomas at old age (Cleary et al., 1986; McDonnell et al., 1989; McDonnell and Korsmeyer, 1991; Tsujimoto and Croce, 1986). Bcl-2 functions as a stabilizer of the mitochondrial membrane, thereby preventing the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and the release of cytochrome c and Apaf-1 in response to glucocorticoids (Susin et al., 1999). In addition, the phosphorylation of Bcl-2 at specific residues is required for the establishment of glucocorticoid resistance in cultured B lymphocytes (Huang and Cidlowski, 2002). A number of in vitro studies have found that Bcl-2 overexpression confers varying degrees of resistance to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis, while in vivo knock-down of Bcl-2 expression sensitizes haematopoietic cells to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis, supporting its role as an important mediator of glucocorticoid resistance in haematomalignancy (Kamada et al., 1995; Kfir et al., 2007; Memon et al., 1995; Nakayama et al., 1993; Veis et al., 1993a, 1993b). In addition, the in vitro and in vivo manipulation of the Bcl-2 family members Bcl-XL and Mcl-1 also alters the efficacy of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis (Opferman et al., 2003; Wei et al., 2006). However, defining the role of these two family members in the development of haematomalignancy and their contribution to glucocorticoid resistance requires further study.

Failure to induce Bim expression

It is well established that the induction of Bim expression is important for glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. Lymphocytes derived from Bim transgenic mice exhibit reduced sensitivity to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis (Bouillet et al., 1999). Furthermore, inhibition of Bim expression via siRNA and shRNA inhibits caspase-3 activation and glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in ALL cell lines (Abrams et al., 2004). A recent study of ALL xenografts in immune-deficient mice revealed that the resistant xenografts all failed to induce Bim expression upon glucocorticoid treatment (Bachmann et al., 2007). This was not due to lack of transactivation activity, as these xenografts were able to induce the expression of GILZ, suggesting that the failure of glucocorticoid-resistant xenografts to induce Bim is downstream of transactivation. Several mechanisms of glucocorticoid-induced Bim expression have been proposed including (1) transactivation of Bim by the glucocorticoid-responsive transcription factors Foxo3A/FKHRL1, RUNX3 and E2F1 (Dijkers et al., 2000; Yamamura et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2005), (2) release of Bim from cytoskeletal sequestration (Puthalakath et al., 1999) and (3) repression of Src-mediated inhibitory phosphorylation of Bim (Ley et al., 2003). Therefore, targeting one or more of the pathways governing glucocorticoid-induced Bim expression may prove a beneficial in the development of therapies to overcome glucocorticoid resistance in haematomalignancies.

Interactions with the kinome

Glucocorticoid signaling involves complex communication between multiple signaling pathways. For example, the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases ERK and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) inhibit glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis, while p38 stimulates glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in the CEM leukemic cell line (Miller et al., 2007; Wada and Penninger, 2004). Glucocorticoid-resistant CEM clones possess high constitutive JNK activity and glucocorticoid stimulation results in increased ERK activity accompanied by the weak induction of p38 (Miller et al., 2007). The cAMP-driven protein kinase A (PKA) pathway also contributes to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. Stimulation of PKA with forskolin inhibits JNK signaling and sensitizes resistant CEM cells to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis by increasing the transcriptional activity of GR (Medh et al., 1998). These results suggest that the GR and PKA pathways exert cooperative effects on GR-mediated gene transcription. Additionally, inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-signaling pathway with rapamycin inhibits JNK signaling, sensitizing CEM and MM cell lines as well as primary MM cells to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. This increased sensitivity is associated with decreased expression of cyclin D2 and the anti-apoptotic protein survivin. The PI3K–AKT pathway has also been shown to prevent glucocorticoid-induced cell death through the inhibitory phophorylation of key apoptotic mediators including Bcl-2-associated death promoter (BAD), caspase 9, Fox03A/FKHRL and CREB (Maddika et al., 2007). Furthermore, the AKT-mediated phospho-inhibition of Fox03A/FKHRL inhibits the transcription of Bim and contributes to glucocorticoid resistance (Maddika et al., 2007). Finally, Src kinase is released from Hsp90 sequestration upon glucocorticoid treatment and pharmacological inhibition of Src activation ameliorates glucocorticoid resistance in MM cells (Ishikawa et al., 2003). Given the intricate cross-talk between various kinase pathways and GR signaling, the modulation of the kinome is a compelling avenue in the development of novel therapies to ameliorate glucocorticoid resistance in haematomalignancies.

Novel therapies targeting glucocorticoid resistance

Targeting the kinome

Previous studies have shown that MAP kinase signaling modulates the response of various leukemic cell lines to glucocorticoids (Miller et al., 2007, 2005). Direct pharmacological inhibition of JNK and ERK signaling sensitizes resistant cells to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis (Miller et al., 2007). A more recent study of five diverse glucocorticoid-resistant haematomalignant cell lines confirmed that inhibition of ERK and JNK signaling results in glucocorticoid sensitivity (Garza et al., 2009). This increased susceptibility to glucocorticoid-induced cell death was directly correlated with increases in total and phospho-GR as well as Bim. Conversely, pharmacological inhibition of p38, one of the kinases responsible for GR phosphorylation at serine 211, protects leukemic cells from glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis (Miller et al., 2005). Mutation of this residue abrogates glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis, suggesting that p38-mediated GR phosphorylation at site 211 is a key component in the glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis signaling cascade (Miller et al., 2005).

Indirect inactivation of JNK signaling via the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin also sensitizes resistant cells to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis through the relief of JNK-mediated phospho-inhibition of Bim (Miller et al., 2007; Stromberg et al., 2004). Additional studies have found that mTOR inhibition leads to decreases in anti-apoptotic Mcl-1 protein expression, further contributing to the sensitization potential of mTOR inhibitors (Wei et al., 2006). Encouragingly, mTOR inhibition sensitizes inherently resistant MM cells and primary MM xenografts to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis and glucocorticoid sensitivity persists despite the addition of exogenous survival signals, suggesting that rapamycin inhibition of mTOR signaling may be a suitable option for the circumvention of glucocorticoid resistance in vivo (Miller et al., 2007; Stromberg et al., 2004).

Stimulation of the cAMP PKA signaling pathway with forskolin sensitizes glucocorticoid-resistant ALL cells to apoptosis (Miller et al., 2007). Furthermore, recent studies have found that inhibiting the activity of three cAMP phosphodiesterases (PDEs) overexpressed in glucocorticoid-resistant CEM cells (PDE3, PDE4 and PDE7) ameliorates glucocorticoid resistance in these cells (Dong et al., 2009). Activation PI3K–AKT signaling is correlated with the expansion of glucocorticoid-resistant MM cells in the bone marrow (Hideshima et al., 2007). Accordingly, inhibition of AKT signaling with perifosine sensitizes resistant MM cells to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis through the reduced expression survival factors including IL-6 and survivin (Hideshima et al., 2007). Currently, a phase III clinical trial is evaluating the efficacy of perifosine and dexamethasone combined chemotherapy in the treatment of drug-resistant MM (Richardson, 2009). In addition, the efficacy of glucocorticoid treatment combined with JNK/ERK inhibitors or mTOR inhibitors is being evaluated clinically in order to overcome the dilemma of glucocorticoid resistance in haematological malignancies (Davies et al., 2007; Mita et al., 2008).

Targeting Bcl-2 family members

Recently, small-molecule BH3 mimics have been developed to impede the anti-apoptotic effects of Bcl-2 family members. These molecules directly interact with anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins at their BH3-binding groove, eliminating their ability to sequester pro-apoptotic BH3 domain Bcl-2 family members (Kang and Reynolds, 2009). For instance, the BH3 mimic gossypol (AT-101) binds directly to Bcl-2 and inhibits its function. Co-treatment with gossypol potentiates dexamethasone-induced cell death in glucocorticoid-resistant MM cell lines and patient-derived primary cells (Kline et al., 2008). The Bcl-2-specific BH3 mimic ABT-737 enhanced dexamethasone-induced cell death via the mitochondrial pathway in five of seven ALL cell lines evaluated (Kang and Reynolds, 2009). Furthermore, addition of the Bcl-2-specific BH3 mimic TW-37 to the CHOP regimen enhanced apoptosis in diffuse large-cell lymphoma xenografts (Mohammad et al., 2007). In addition to Bcl-2-targeted BH3 mimics, the Mcl-1-specific inhibitor obatoclax also enhanced glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis (Trudel et al., 2007). Co-administration of obatoclax and dexamethasone overcame glucocorticoid resistance in 15 of 16 patient-derived MM primary cell lines. In these cells, Mcl-1 inhibition was associated with an increase in Bim expression. Finally, anti-sense antagonism of Bcl-2 with the G3139 oligonucleotide resulted in decreased Bcl-2 protein expression and an enhanced response to dexamethasone/thalidomide chemotherapy in phase II clinical trials (Badros et al., 2005). The efficacy of G3139/dexamethasone combined therapy in the treatment of MM is currently being evaluated in phase III clinical trials (Kang and Reynolds, 2009).

Interestingly, glucocorticoid monotherapy results in the decreased expression of the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member Noxa in pediatric ALL samples. Conditional overexpression of Noxa in CEM ALL cells accelerated glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis (Ploner et al., 2009). Therefore, future therapies interfering with glucocorticoid-induced Noxa down-regulation may improve the efficacy of glucocorticoid therapy in childhood ALL.

Concluding remarks

Glucocorticoids exert pleiotrophic physiological effects, including the induction of apoptosis in the lymphocyte compartment. Glucocorticoid effects are mediated through the GR, a ligand-activated transcription factor. GR transactivation is required for the induction of apoptosis, primarily, the induction of Bim expression is important for the apoptotic activity of glucocorticoids. However, glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis is a highly coordinated, multi-component process. The rapid cytoplasmic effects of glucocorticoids may also contribute to the progression of apoptosis. However, the precise role of these cytoplasmic effects in the advancement of glucocorticoid-induced cell death in lymphocytes requires further investigative scrutiny. Endogenous glucocorticoids shape the T-cell repertoire through the induction of apoptosis by neglect as well as the antagonism of TCR-induced apoptosis during positive selection. Owing to their ability to induce apoptosis in lymphocytes, synthetic glucocorticoids are widely used in the treatment of haematological malignancies. Glucocorticoid chemotherapy is limited by the emergence of glucocorticoid-resistant clonal populations following prolonged glucocorticoid therapy, glucocorticoid resistance upon relapse and the existence of inherently resistant haematomalignancies. The mechanisms involved in the development of glucocorticoid resistance are complex and cell-type specific. Altered expression ratios of GR isoforms, homologous down-regulation of GR, the inability to auto-induce GR, mutations in the GR, dysregulation of Bcl2 family members, the failure to induce Bim and interactions with the kinome may all contribute to the formation of glucocorticoid resistance in haematomalignancies. The development of novel therapies to overcome glucocorticoid resistance in haematomaligancy, including specific targeting of the kinome and Bcl-2 family members, will dramatically improve the efficacy of glucocorticoid therapy in the treatment of haematological malignancies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Robert Oakley, Dr. Carl Bortner and Alyson Scoltock for their editorial contributions to this manuscript. We also thank Sue Edelstein for her expert assistance in graphics preparation.

References

- Abrams MT, Robertson NM, Yoon K, Wickstrom E. Inhibition of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis by targeting the major splice variants of BIM mRNA with small interfering RNA and short hairpin RNA. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:55809–55817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411767200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adcock IM. Glucocorticoid-regulated transcription factors. Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2001;14:211–219. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2001.0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alksnis M, Barkhem T, Stromstedt PE, Ahola H, Kutoh E, Gustafsson JA, et al. High level expression of functional full length and truncated glucocorticoid receptor in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Demonstration of ligand-induced down-regulation of expressed receptor mRNA and protein. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266:10078–10085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi A, Dixit VM. Death receptors: Signaling and modulation. Science. 1998;281:1305–1308. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwell JD, Lu FW, Vacchio MS. Glucocorticoids in T cell development and function . Annual Review of Immunology. 2000;18:309–345. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayroldi E, Zollo O, Bastianelli A, Marchetti C, Agostini M, Di Virgilio R, et al. GILZ mediates the anti-proliferative activity of glucocorticoids by negative regulation of ras signaling. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117:1605–1615. doi: 10.1172/JCI30724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann PS, Gorman R, Papa RA, Bardell JE, Ford J, Kees UR, et al. Divergent mechanisms of glucocorticoid resistance in experimental models of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Research. 2007;67:4482–4490. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badros AZ, Goloubeva O, Rapoport AP, Ratterree B, Gahres N, Meisenberg B, et al. Phase II study of G3139, a bcl-2 antisense oligonucleotide, in combination with dexamethasone and thalidomide in relapsed multiple myeloma patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:4089–4099. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.14.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AF, Briehl MM, Dorr R, Powis G. Decreased antioxidant defence and increased oxidant stress during dexamethasone-induced apoptosis: Bcl-2 prevents the loss of antioxidant enzyme activity. Cell Death Differentiation. 1996;3:207–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamberger CM, Bamberger AM, de Castro M, Chrousos GP. Glucocorticoid receptor beta, a potential endogenous inhibitor of glucocorticoid action in humans. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1995;95:2435–2441. doi: 10.1172/JCI117943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett TJ, Vig E, Vedeckis WV. Coordinate regulation of glucocorticoid receptor and c-Jun gene expression is cell type-specific and exhibits differential hormonal sensitivity for down- and up-regulation. Biochemistry. 1996;35:9746–9753. doi: 10.1021/bi960058j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann S, Dostert A, Novac N, Bauer A, Schmid W, Fas SC, et al. Glucocorticoids inhibit activation-induced cell death (AICD) via direct DNA-dependent repression of the CD95 ligand gene by a glucocorticoid receptor dimer. Blood. 2005;106:617–625. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beesley AH, Weller RE, Senanayake S, Welch M, Kees UR. Receptor mutation is not a common mechanism of naturally occurring glucocorticoid resistance in leukaemia cell lines. Leukemia Research. 2009;33:321–325. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellosillo B, Dalmau M, Colomer D, Gil J. Involvement of CED-3/ICE proteases in the apoptosis of B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Blood. 1997;89:3378–3384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson RS, Heer S, Dive C, Watson AJ. Characterization of cell volume loss in CEM-C7A cells during dexamethasone-induced apoptosis. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;270:C1190–C1203. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.4.C1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian X, Hughes FM, Jr., Huang Y, Cidlowski JA, Putney JW., Jr. Roles of cytoplasmic ca2+ and intracellular ca2+ stores in induction and suppression of apoptosis in S49 cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:C1241–C1249. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.4.C1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black BE, Holaska JM, Rastinejad F, Paschal BM. DNA binding domains in diverse nuclear receptors function as nuclear export signals. Current Biology. 2001;11:1749–1758. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00537-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bledsoe RK, Montana VG, Stanley TB, Delves CJ, Apolito CJ, McKee DD, et al. Crystal structure of the glucocorticoid receptor ligand binding domain reveals a novel mode of receptor dimerization and coactivator recognition. Cell. 2002;110:93–105. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00817-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield CD, Smith KA, Peterson BA, Munck A. Glucocorticoid receptors in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Research. 1981;41:4857–4860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortner CD, Cidlowski JA. Volume regulation and ion transport during apoptosis. Methods of Enzymology. 2000;322:421–433. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)22041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortner CD, Hughes FM, Jr., Cidlowski JA. A primary role for K+ and Na+ efflux in the activation of apoptosis. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:32436–32442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosanquet AG, McCann SR, Crotty GM, Mills MJ, Catovsky D. Methylprednisolone in advanced chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: Rationale for, and effectiveness of treatment suggested by DiSC assay. Acta Haematology. 1995;93:73–79. doi: 10.1159/000204115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouillet P, Metcalf D, Huang DC, Tarlinton DM, Kay TW, Kontgen F, et al. Proapoptotic Bcl-2 relative bim required for certain apoptotic responses, leukocyte homeostasis, and to preclude autoimmunity. Science. 1999;286:1735–1738. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouillet P, Zhang LC, Huang DC, Webb GC, Bottema CD, Shore P, et al. Gene structure alternative splicing, and chromosomal localization of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 relative bim. Mammalian Genome. 2001;12:163–168. doi: 10.1007/s003350010242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslin MB, Geng CD, Vedeckis WV. Multiple promoters exist in the human GR gene, one of which is activated by glucocorticoids. Molecular Endocrinology. 2001;15:1381–1395. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.8.0696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JA, Khor B, Vogt SK, Muglia LM, Fujiwara H, Haegele KE, et al. T-cell glucocorticoid receptor is required to suppress COX-2-mediated lethal immune activation. Nature Medicine. 2003;9:1318–1322. doi: 10.1038/nm895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstein KL, Jewell CM, Cidlowski JA. Human glucocorticoid receptor cDNA contains sequences sufficient for receptor down-regulation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265:7284–7291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstein KL, Jewell CM, Sar M, Cidlowski JA. Intragenic sequences of the human glucocorticoid receptor complementary DNA mediate hormone-inducible receptor messenger RNA down-regulation through multiple mechanisms. Molecular Endocrinology. 1994;8:1764–1773. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.12.7708063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro JE, James DF, Sandoval-Sus JD, Jain S, Bole J, Rassenti L, et al. Rituximab in combination with high-dose methylprednisolone for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23:1779–1789. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmandari E, Kino T, Souvatzoglou E, Vottero A, Bhattacharyya N, Chrousos GP. Natural glucocorticoid receptor mutants causing generalized glucocorticoid resistance: Molecular genotype, genetic transmission, and clinical phenotype. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2004;89:1939–1949. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Shyu AB. AU-rich elements: Characterization and importance in mRNA degradation. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 1995;20:465–470. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung J, Smith DF. Molecular chaperone interactions with steroid receptors: An update. Molecular Endocrinology. 2000;14:939–946. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.7.0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrysis D, Zaman F, Chagin AS, Takigawa M, Saven-dahl L. Dexamethasone induces apoptosis in proliferative chondrocytes through activation of caspases and suppression of the Akt-phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase signaling pathway. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1391–1397. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifone MG, Migliorati G, Parroni R, Marchetti C, Millimaggi D, Santoni A, et al. Dexamethasone-induced thymocyte apoptosis: Apoptotic signal involves the sequential activation of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C, acidic sphingomyelinase, and caspases. Blood. 1999;93:2282–2296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary ML, Smith SD, Sklar J. Cloning and structural analysis of cDNAs for bcl-2 and a hybrid bcl-2/ immunoglobulin transcript resulting from the t(14;18) trans-location. Cell. 1986;47:19–28. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90362-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]