Abstract

A systematic review was conducted to identify and qualitatively analyze the methods as well as recommendations of Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) and Best Practice Statements (BPS) concerning varicocele in the pediatric and adolescent population. An electronic search was performed with the MEDLINE, EMBASE, Science Direct, and Scielo databases, as well as guidelines’ Web sites until September 2015. Four guidelines were included in the qualitative synthesis. In general, the recommendations provided by the CPG/BPS were consistent despite the existence of some gaps across the studies. The guidelines issued by the American Urological Association (AUA) and American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) did not provide evidence-based levels for the recommendations given. Most of the recommendations given by the European Association of Urology (EAU) and European Society of Pediatric Urology (ESPU) were derived from nonrandomized clinical trials, retrospective studies, and expert opinion. Among all CPG/BPS, only one was specifically designed for the pediatric population. The studied guidelines did not undertake independent cost-effectiveness and risk-benefit analysis. The main objectives of these guidelines were to translate the best evidence into practice and provide a framework of standardized care while maintaining clinical autonomy and physician judgment. However, the limitations identified in the CPG/BPS for the diagnosis and management of varicocele in children and adolescents indicate ample opportunities for research and future incorporation of higher quality standards in patient care.

Keywords: adolescent, best practice statements, child, clinical practice guidelines varicocele, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Varicocele is defined as an abnormal dilatation of testicular veins in the pampiniform plexus associated with venous reflux. It is one of the most common genital conditions referred to pediatric urologists.1 Although varicocele is rarely seen in the preadolescent age group (2–10 years), in which the prevalence is about 0.92%,2 it becomes more common at the onset of puberty. In a large study involving 6200 boys aged 0–19 years, varicocele was detected in 7.9% of subjects within the age group of 10–19 years.3 These findings have been corroborated by others who found varicocele affecting 6%–26% of adolescents, mostly (78%–93% of cases) on the left side.2,4,5,6,7

Adolescent varicocele has been associated with testicular volume loss, endocrine abnormalities, and abnormal semen parameters.8 Testicular histological findings in children and adolescents with varicocele are similar to those observed in infertile men. It has been postulated that varicocele-associated heat stress, androgen deprivation, and accumulation of toxic metabolites induce apoptotic pathways leading to the observed detrimental effects. Severe testicular damage was found in 20% of the adolescents while 46% of the affected subjects presented with mild to moderate testicular abnormalities. Testicular hypotrophy was more common in patients with varicoceles of higher grade; 70% of the affected adolescents were diagnosed with varicocele grades 2 and 3.7

Although the actual benefit of varicocele treatment in children and adolescents is still debatable, several authors have reported testicular catch-up growth after varicocelectomy.9,10 It has been shown that fertility problems will arise later in life in about 20% of adolescents with varicocele,11 thus arguing in favor of performing an early intervention to avoid disease progression.12,13 Nevertheless, the majority of adolescents with varicocele retain fertility in adulthood, and thus current research is focused on identifying the adolescents more likely to benefit from interventional therapy.14

Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) and Best Practice Statements (BPS) have emerged to offer advantages in standardization of care. They are aimed at improving efficiency, enhancing research opportunities, and creating a cost-effective diagnosis/treatment algorithm.15 Although some physicians opt not to adopt guidelines for various reasons, including financial, technical, and personal factors, a combination of guidelines-based management and physician judgment is likely to represent the most prevailing standard of care.

Guidelines statements are not intended to be used as a “legal standard” against which physicians should be measured but rather serve to provide a framework of standardized care while maintaining clinical autonomy and physician judgment.16 The Institute of Medicine states that the clinical practice guidelines should be developed based on a systematic review of the evidence, and the final document must include statements and recommendations intended to optimize patient care and assist physicians and/or other health care practitioners, and review of patients to make decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances.17

The role for and utility of clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of the children and adolescents with varicocele is to help pediatric urologists and other health care professionals to enhance the quality of health care, and simultaneously discourage potentially harmful or ineffective interventions during evaluation and management. Although these guidelines attempt to translate the best evidence into practice, there are significant differences in the methods of guidelines’ development, data collection and analysis, which influence both the quality and strength of statements made and recommendations provided. Thus, we performed this systematic review aiming at identifying recently developed CPG and BPS concerning varicocele in the pediatric and adolescent population, and to review their methodology and consistency of recommendations given.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement to report the results of this review.18 The study was exempted from Institutional Review Board approval, as there was no direct intervention in humans.

Search strategy

An electronic search was conducted with the MEDLINE, EMBASE, Science Direct and Scielo databases until September 2015. The electronic database search was supplemented by searching guidelines websites; specifically, we searched “Guidelines International Network” (G-I-N; www.g-i-n.net), “National Guidelines Clearinghouse” (www.guideline.gov), and “National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence” (NICE; www.nice.org.uk) websites. We used relevant terms, namely “varicocele,” “child,” and “adolescent” AND “guidelines,” “best practice statements,” and “committee opinion.”

Eligibility criteria

Only CPG and BPS that were endorsed by a national governmental or provider organization related to the evaluation and management of children and adolescents with varicocele were included in the qualitative synthesis. In addition, only documents written in English were included.

Study selection

In the first screening, both authors assessed all abstracts retrieved from the search and then obtained the full documents that fitted the inclusion criteria. They evaluated the studies’ eligibility and quality and extracted the data. Any discrepancies were resolved by mutual agreement.

Data collection process and data items

One reviewer independently extracted all relevant data. The extracted data included guideline characteristics (e.g., objective, intended users, rating scheme for the strength of the evidence and recommendation, method of validation, year of dissemination, development team, funding organization, clinical algorithm, and implementation strategy) and methods of development and recommendations given in Table 1.

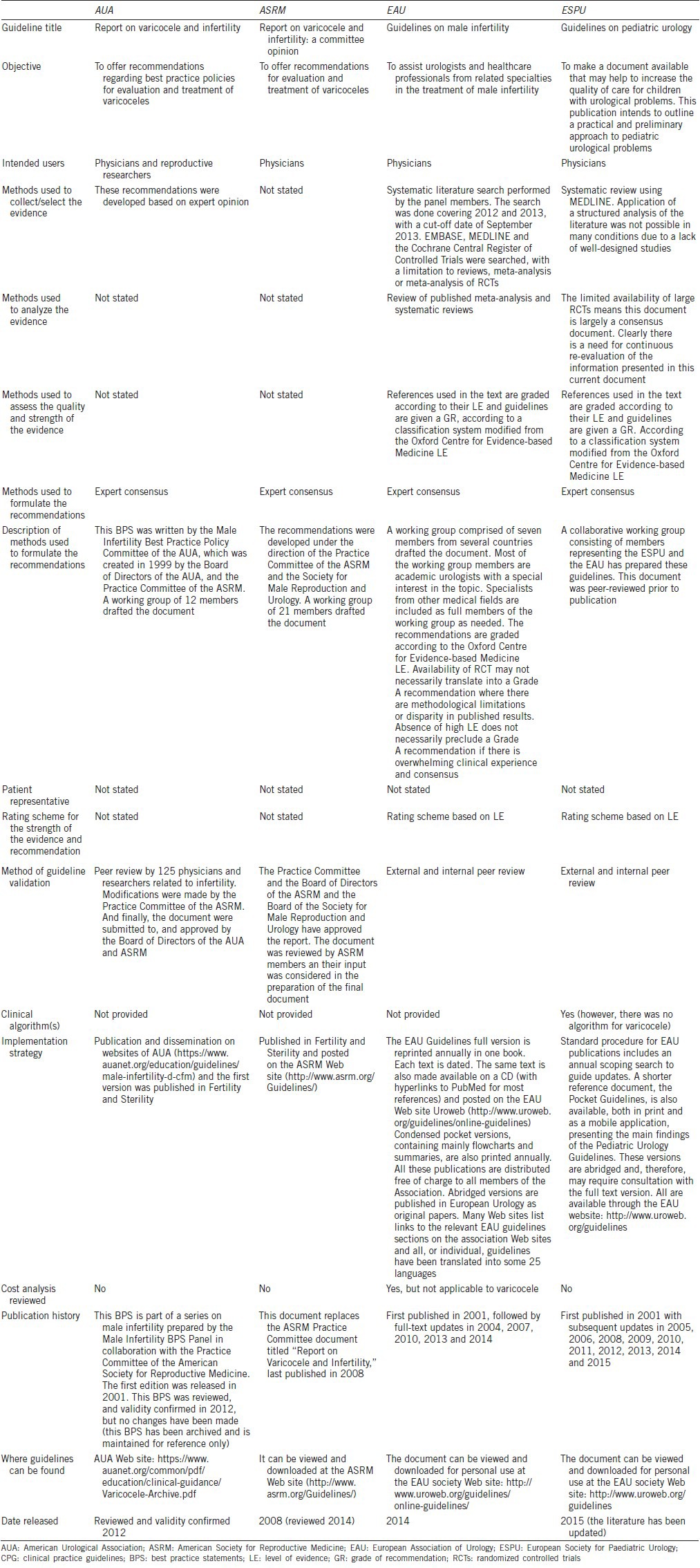

Table 1.

Scope and methods used to formulate the CPG and BPS for varicocele in children and adolescents

Synthesis of results

The included CPG and BPS were summarized and analyzed qualitatively according to the scope and methods used for their formulation. We evaluated whether the guidelines made specific recommendations, the level of evidence (based on the design of supporting studies referenced), and the grade of recommendation (determined when the guidelines panel critically appraised the supporting studies referenced). The following descriptive categories were used to compare the CPG and BPS: (i) diagnosis; (ii) treatment indication; (iii) treatment method.

RESULTS

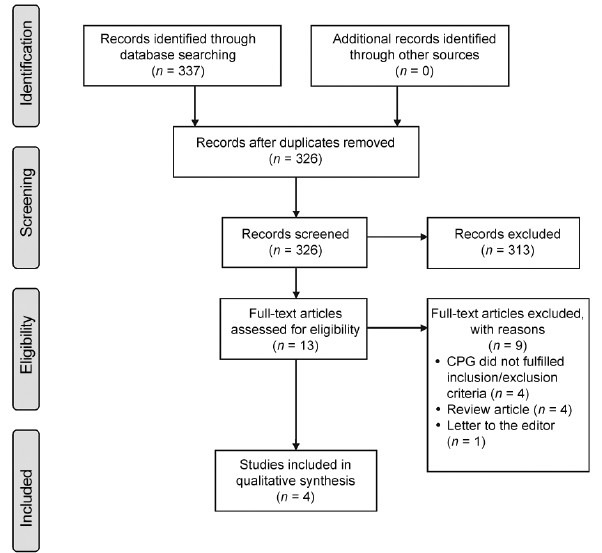

Our electronic search retrieved 337 articles, of which 13 were considered for full-text screening. Among these, nine articles were excluded. The reasons for exclusion were: (1) did not fulfill the inclusion criteria concerning the target population;19,20,21,22 (2) review article with recommendation statements not endorsed by governmental or provider organization;14 (3) review articles;7,23,24 and (4) letter to the editor.25 Four articles were ultimately included in the qualitative analysis.6,26,27,28 The complete selection process is depicted in Figure 1. The guidelines from the European Association of Urology (EAU)27 and European Society of Paediatric Urology (ESPU)6 represented a multinational effort while the guidelines from the American Urological Association (AUA)26 and American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM)28 were conducted within the United States. Only the ESPU guidelines were specifically designed for children and adolescents while the remaining guidelines focused on both adolescent and adult varicocele. As far as the AUA BPS is concerned, it is listed as it had been updated and validated in 2012 according to the AUA website; however, neither changes have been included to the previous 2001 version, nor an updated version has been released.

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the identification and selection process of studies included in the systematic review.

Guideline characteristics

The scope and methods related to guidelines development are depicted in Table 1. Of them, the EAU and ESPU guidelines provided evidence-based levels for the recommendations given (Supplementary Table 1 (862.8KB, tif) ). Most of the recommendations were derived from nonrandomized clinical trials, retrospective studies, and expert opinion. The recommendations for diagnosis and treatment are summarized in Table 2.

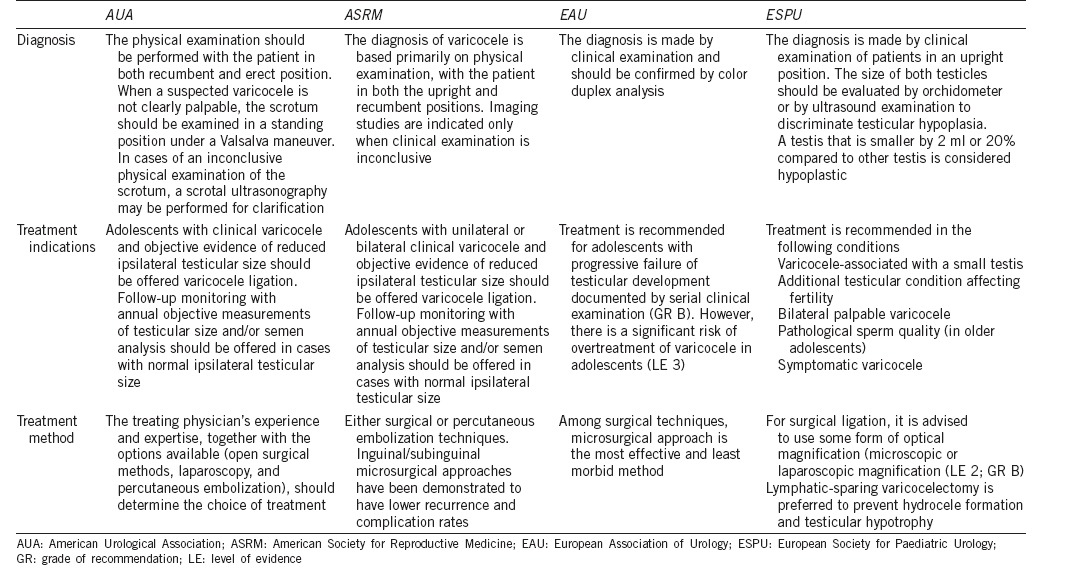

Table 2.

Guidelines recommendations on diagnosis, treatment indications and treatment methods for children and adolescents with varicocele

Levels of evidence and grades of recommendation used in the EAU and ESPU clinical guidelines

Guidelines recommendations

Diagnosis

AUA and ASRM guidelines

According to both the AUA and ASRM guidelines, a palpable varicocele can be detected in erect position and feels like a “bag of worms,” and it disappears or very significantly diminishes in size when the patient is recumbent. If the varicocele is not clearly palpable, a repeat examination is advised in erect position with Valsalva maneuver. The AUA guidelines recommend that the physical examination should be performed with the patient in both recumbent and erect position.

Both guidelines recommend that clinicians grade varicoceles on a scale of 1 to 3, in which grade 3 is visually inspected, grade 2 is easily palpable, and grade 1 is only palpable with Valsalva maneuver.29 These definitions are rather equivocal and subjective definitions, as what may be an easily palpable varicocele to one examiner may not be for another. However, there is agreement that varicoceles palpable by most examiners are considered “clinically significant,” and only these have been clearly associated with infertility. Scrotal ultrasonography is indicated for evaluation of a questionable physical examination of the scrotum. Although decisive evidence-based criteria for ultrasonography diagnosis of varicocele are lacking, the current consensus agrees that multiple spermatic veins >2.5–3.0 mm in diameter (at rest and with Valsalva) tend to correlate with the presence of clinically significant varicoceles.30

EAU and ESPU guidelines

The EAU and ESPU guidelines recommend that the diagnosis of varicocele be initially made by clinical examination in the upright position.6,27,29 Clinically, varicocele is graded in the same manner as stated by the AUA/ASRM guidelines.6 The size of the testis should be evaluated during palpation to detect a smaller testis. To discriminate testicular hypoplasia, the testicular volume is measured by ultrasound examination or using an orchidometer. In adolescents, a testis that is smaller by more than 2 ml or 20% compared to the other testis is considered to be hypoplastic31 (Level of evidence 2). In order to assess testicular injury in adolescents with varicocele, supranormal follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) responses to the luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) stimulation test are considered reliable, because histopathological testicular changes have been found in these patients.32,33

The EAU also recommends that varicocele diagnosis be confirmed by color Doppler analysis in the supine and upright position.27 Venous reflux into the pampiniform plexus should be noted using Doppler color flow mapping in the supine and upright position; however, it is considered subclinical varicocele if reflux is present but varicocele is not palpable.

In the ESPU guidelines, there is also a recommendation to perform renal ultrasound examination in prepubertal boys and in patients with isolated right varicocele, as extension of Wilms tumor into the renal vein and inferior vena cava may be associated with a secondary varicocele (Level of evidence 4).6

Treatment indication

ASRM and AUA guidelines

According to both guidelines, adolescent males who have a unilateral or bilateral varicocele and objective evidence of testicular hypotrophy ipsilateral to the varicocele may be considered candidates for varicocele ligation.10,32,34,35 However, none of these guidelines provide a definition for “testicular hypotrophy.” If no reduction in testicular size is evident, annual objective measurement of testis size and/or semen analyses to monitor for earliest sign of varicocele-related testicular injury is recommended. Varicocele repair may be offered on detection of testicular or semen abnormalities, as catch-up growth has been demonstrated as well as the reversal of semen abnormalities; however, these guidelines also acknowledge that data are lacking regarding the impact of treatment on future fertility.

EAU and ESPU guidelines

The EAU guidelines recommend varicocele treatment to adolescents with progressive failure of testicular development documented by serial clinical examination (Grade B recommendation). On the other hand, the ESPU guidelines indicate that the criteria for varicocelectomy in children and adolescents are as follows:

Varicocele associated with a small testis

Additional testicular condition affecting fertility

Bilateral palpable varicocele

Pathological sperm quality (in older adolescents)

Symptomatic varicocele.

The latter also states that testicular (left + right) volume loss in comparison with normal testes is a promising indication criterion provided the normal values are available.36 The ESPU defines testicular hypoplasia as a testis that is smaller by >2 ml or 20% compared to the other testis (Level of evidence 2). Repair of a large varicocele, physically or psychologically causing discomfort, may also be considered. Other varicoceles should be followed-up until a reliable sperm analysis can be performed (Level of evidence 4). These aforesaid guidelines add that there is no evidence that treatment of varicocele at pediatric age will offer a better andrological outcome than an operation performed later (Level of evidence 4).

Treatment method

ASRM and AUA guidelines

The ASRM and AUA guidelines concur that both surgery and percutaneous embolization may be performed when considering the varicocele repair. The surgery techniques include: open retroperitoneal, inguinal, and subinguinal approaches or laparoscopy. Percutaneous embolization treatment of varicocele is accomplished by percutaneous embolization of the refluxing internal spermatic vein(s). These guidelines acknowledge that there are differences in recurrence rates between the techniques, and state that any of these methods has been proven superior to the others in its ability to improve fertility.

EAU and ESPU guidelines

According to the EAU and ESPU guidelines, the type of intervention chosen depends mainly on the experience of the therapist. Although laparoscopic varicocelectomy is feasible, it must be justified in terms of cost-effectiveness. Current evidence indicates that microsurgical varicocelectomy is the most effective and least morbid method among the varicocelectomy techniques.37 For surgical ligation, some forms of optical magnification (microscopic or laparoscopic magnification) should be used in children and adolescents, which yields a recurrence rate lower than 10%. Lymphatic-sparing varicocelectomy is preferred to prevent hydrocele formation and testicular hypertrophy (Level of evidence 2; Grade B recommendation).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review evaluating CPG and BPS related to varicocele in children (under 10 years old) and adolescents (from ages 10–19 years old). Although the included studies differ in the quality with regard to scientific rigor, stakeholder representation, and implementation applicability, all of them clearly presented their recommendations.

Delivering outstanding medical care requires providing care that is both effective and safe. Nevertheless, many times the practice does not follow scientific evidence.38 According to Greenhalgh and colleagues, the following principles should be followed to achieve a real evidence-based medicine: (i) the ethical care of the patients should be made its top priority; (ii) individualized evidence in a format that clinicians and patients can understand should be demanded; (iii) delivery of care should be characterized by expert judgment rather than mechanical rule following; (iv) decisions should be shared with patients through meaningful conversations; (v) a strong clinician-patient relationship should be built in all the aspects of care; (vi) the aforesaid principles should be applied at the community level for evidence-based public health.39 When evaluating guidelines’ scope and methods (Table 1), it seems that many of these principles have been followed. All guidelines stated their objectives and included the intended users, the methods used to develop, analyze the evidence as well as to formulate the recommendations. The guidelines included in this review are informative with a chance to influence the readers really positively. This is important because failure to properly inform, inspire, and/or influence final users may otherwise render guidelines ineffective or impractical.40 However, there is a lack of information about the cost-effectiveness and risk-benefit analysis of the techniques employed to treat the patients concerned.

Importantly, none of the studied guidelines had patient representatives (or parents/guardians as representatives of patients’ welfare) included in their workgroup panel. As previously discussed, another precondition for real evidence-based medicine is patient-centeredness. Providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions are the pillars of patient-centeredness.17,41,42 Therefore, guidelines developers should consider integrating “patient” representatives in future guidelines’ updates to make them even more comprehensive.

It dates from more than 20 years that a new paradigm for teaching and practicing clinical medicine was announced, and the clinical practice guidelines movement became alive.43 From that time onward, it has been suggested that the ideal medical practice should take into consideration the combination of the evidence from high quality randomized controlled trials and observational studies, with clinical experience and the needs and wishes of patients.39 On the other hand, evidence has shown that it takes approximately 5 years for given clinical guidelines to be adopted into routine practice, and even the broadly accepted guidelines are often not fully followed.41,42 A reason influencing guidelines’ adoption relates to the implementation strategy as to provide an easy way of knowledge dissemination. In this study, all guidelines were made easily accessible to all who might be interested through the societies’ websites. As far the EAU and EPSU guidelines are concerned, they have been translated into some 25 languages making it easier to disseminate the information.6 Although efforts to establish a clear implementation strategy, as seen in the EAU and EPSU guidelines, may facilitate health care professionals to adopt guidelines into daily practice, differences in physicians’ clinical practices could also have an impact on implementation of guidelines.

In general, the recommendations provided by the CPG were consistent despite some gaps across the studied guidelines. For instance, the AUA and ASRM guidelines did not provide evidence-based levels for the recommendations given. Moreover, most of the recommendations given by the EAU and ESPU guidelines were derived from nonrandomized clinical trials, retrospective studies, and expert opinion. Among all CPGs, only one was specifically designed for the pediatric population; the EAU Guidelines on Pediatric Urology includes a dedicated chapter on the diagnosis and management of children and adolescent varicocele.6 Notably, children and adolescent varicocele were included as subsections within the varicocele chapter in the EAU guidelines on male infertility. Similarly, both the AUA and ASRM included the topic of children and adolescent varicocele as a subsection of its guideline on varicocele. This is probably due to the paucity of information on the matter concerned, and reinforces the need of well-designed studies regarding varicocele in this subgroup of patients.

We also noted differences between the European and American approach to varicocele diagnosis and management. The EAU and ESPU guidelines were more detailed with regard to establishing the diagnosis, and they provided a wider range of indications for treatment. However as previously discussed, most of the recommendations were derived from nonrandomized clinical trials, retrospective studies, and expert opinion.

Future perspectives

The main objective of every CPG is to translate the best evidence into practice and serve to provide a framework of standardized care while maintaining clinical autonomy and physician judgment. Developers are encouraged to constantly revise guidelines and incorporate clear statements as to indicate for what purpose such guidelines were developed, who are the final users, and under what constraints they should be applied. It is equally important to include nonhealth care practitioners’ representatives, including patient representation whenever applicable, in order to ensure patients’ needs are also taken into account. The limitations encountered in the studied CPG and BPS for the diagnosis and management of children and adolescents with varicocele indicate ample opportunities for research and future incorporation of higher quality standards in the care of these patients.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MR participated in the acquisition of data and drafted the manuscript. SCE designed and coordinated the study, participated in the acquisition of data, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Asian Journal of Andrology website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kolon TF. Evaluation and management of the adolescent varicocele. J Urol. 2015;194:1194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akbay E, Cayan S, Doruk E, Duce MN, Bozlu M. The prevalence of varicocele and varicocele-related testicular atrophy in Turkish children and adolescents. BJU Int. 2000;86:490–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumanov P, Robeva RN, Tomova A. Adolescent varicocele: who is at risk? Pediatrics. 2008;121:e53–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oster J. Varicocele in children and adolescents. An investigation of the incidence among Danish school children. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1971;5:27–32. doi: 10.3109/00365597109133569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger OG. Varicocele in adolescence. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1980;19:810–1. doi: 10.1177/000992288001901205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vasavada S, Ross J, Nasrallah P, Kay R. Prepubertal varicoceles. Urology. 1997;50:774–7. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tekgul S, Dogan HS, Erdem E, Hoebeke P, Kocvara R, et al. EAU Guidelines on Paediatric Urology 2015: European Association of Urology and European Society of Paediatric Urology. [Last accessed on 2015 Sep 30]. Available from: http://www.uroweb.org/guideline/paediatric-urology/

- 8.Bong GW, Koo HP. The adolescent varicocele: to treat or not to treat. Urol Clin North Am. 2004;31:509–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kass EJ, Belman AB. Reversal of testicular growth failure by varicocele ligation. J Urol. 1987;137:475–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)44072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paduch DA, Niedzelski J. Repair versus observation in adolescent varicocele: a prospective study. J Urol. 1997;158:1128–32. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199709000-00111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. The influence of varicocele on parameters of fertility in a large group of men presenting to infertility clinics. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:1289–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laven JS, Haans LC, Mali WP, te Velde ER, Wensing CJ, et al. Effects of varicocele treatment in adolescents: a randomized study. Fertil Steril. 1992;58:756–62. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)55324-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinto KJ, Kroovand RL, Jarow JP. Varicocele related testicular atrophy and its predictive effect upon fertility. J Urol. 1994;152:788–90. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32710-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waalkes R, Manea IF, Nijman JM. Varicocele in adolescents: a review and guideline for the daily practice. Arch Esp Urol. 2012;65:859–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esteves SC, Chan P. A systematic review of recent clinical practice guidelines and best practice statements for the evaluation of the infertile male. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015;47:1441–56. doi: 10.1007/s11255-015-1059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trost LW, Nehra A. Guideline-based management of male infertility: why do we need it? Indian J Urol. 2011;27:49–57. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.78426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham R, Manchar M, Wolman DM, Greenfield S, Steinberg E. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2011. [Last accessed on 2015 Sep 30]. Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Available from: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2011/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines-We-Can-Trust/Standards.aspx . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:332–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarow J, Sigman M, Kolettis PN, Lipshultz L, McClure RD, et al. The Optimal Evaluation of the Infertile Male: Best Practice Statement. 2010. [Last accessed on 2015 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.auanet.org/education/guidelines/male-infertility-d.cfm .

- 20.American College of Radiology (ACR), American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM), Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound (SRU). ACR-AIUM-SRU practice guideline for the performance of scrotal ultrasound examinations. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34:1–5. doi: 10.7863/ultra.34.8.15.13.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.London: NICE; 2013. [Last accessed on 2015 Sep 30]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Fertility: assessment and treatment for people with fertility problems. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG156 . [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcell AV. Philadelphia, PA: Male Training Center for Family Planning and Reproductive Health and Rockville, MD: Office of Population Affairs; 2014. Male Training Center for Family Planning and Reproductive Health. Preventive Male Sexual and Reproductive Health Care: Recommendations for Clinical Practice; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diamond DA, Gargollo PC, Caldamone AA. Current management principles for adolescent varicocele. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:1294–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masson P, Brannigan RE. The varicocele. Urol Clin North Am. 2014;41:129–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajfer J. Varicocele: practice guidelines. Rev Urol. 2007;9:161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharlip ID, Jarow J, Belker AM, Darnewood M, Howards SS, et al. Report on Varicocele and Infertility. [Last accessed on 2015 Sep 30]. Available from: https://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Varicocele-Archive.pdf .

- 27.Jungwirth A, Diemer T, Dohle GR, Giwercman A, Kopa Z, et al. EAU Guidelines of Male Infertility. 2013. [Last accessed on 2015 Sep 30]. Available from: http://www.uroweb.org/guideline/male-infertility/

- 28.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Society for Male Reproduction and Urology. Report on varicocele and infertility: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:1556–60. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dubin L, Amelar RD. Varicocele size and results of varicocelectomy in selected subfertile men with varicocele. Fertil Steril. 1970;21:606–9. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)37684-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stahl P, Schlegel PN. Standardization and documentation of varicocele evaluation. Curr Opin Urol. 2011;21:500–5. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32834b8698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diamond DA, Zurakowski D, Bauer SB, Borer JG, Peters CA, et al. Relationship of varicocele grade and testicular hypotrophy to semen parameters in adolescents. J Urol. 2007;178:1584–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okuyama A, Nakamura M, Namiki M, Takeyama M, Utsunomiya M, et al. Surgical repair of varicocele at puberty: preventive treatment for fertility improvement. J Urol. 1988;139:562–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)42525-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aragona F, Ragazzi R, Pozzan GB, De Caro R, Munari PF, et al. Correlation of testicular volume, histology and LHRH test in adolescents with idiopathic varicocele. Eur Urol. 1994;26:61–6. doi: 10.1159/000475344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamamoto M, Katsuno S, Yokoi K, Hibi H, Miyake K. The effect of varicocelectomy on testicular volume in infertile patients with varicoceles. Nagoya J Med Sci. 1995;58:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sigman M, Jarow JP. Ipsilateral testicular hypotrophy is associated with decreased sperm counts in infertile men with varicoceles. J Urol. 1997;158:605–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen JJ, Ahn HJ, Junewick J, Posey ZQ, Rambhatla A, et al. Is the comparison of a left varicocele testis to its contralateral normal testis sufficient in determining its well-being? Urology. 2011;78:1167–72. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ding H, Tian J, Du W, Zhang L, Wang H, et al. Open non-microsurgical, laparoscopic or open microsurgical varicocelectomy for male infertility: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BJU Int. 2012;110:1536–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bates DW, Kuperman GJ, Wang S, Gandhi T, Kittler A, et al. Ten commandments for effective clinical decision support: making the practice of evidence-based medicine a realty. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10:523–30. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greenhalgh T, Howick J, Maskrey N. Evidence Based Medicine Renaissance Group. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? BMJ. 2014;13:g3725. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lavis JN, Davies HT, Gruen RL, Walshe K, Farquhar CM. Working within and beyond the Cochrane Collaboration to make systematic reviews more useful to healthcare managers and policy makers. Healthc Policy. 2006;1:21–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grimshaw JM, Russell IT. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet. 1993;342:1317–22. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92244-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical guidelines?. A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Casey DE., Jr Why don’t physicians (and patients) consistently follow clinical practice guidelines? JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1581–3. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.7672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Levels of evidence and grades of recommendation used in the EAU and ESPU clinical guidelines