Abstract

Traditionally, the success of a researcher is assessed by the number of publications he or she publishes in peer-reviewed, indexed, high impact journals. This essential yardstick, often referred to as the impact of a specific researcher, is assessed through the use of various metrics. While researchers may be acquainted with such matrices, many do not know how to use them to enhance their careers. In addition to these metrics, a number of other factors should be taken into consideration to objectively evaluate a scientist's profile as a researcher and academician. Moreover, each metric has its own limitations that need to be considered when selecting an appropriate metric for evaluation. This paper provides a broad overview of the wide array of metrics currently in use in academia and research. Popular metrics are discussed and defined, including traditional metrics and article-level metrics, some of which are applied to researchers for a greater understanding of a particular concept, including varicocele that is the thematic area of this Special Issue of Asian Journal of Andrology. We recommend the combined use of quantitative and qualitative evaluation using judiciously selected metrics for a more objective assessment of scholarly output and research impact.

Keywords: article-level metrics, bibliometrics, citation counts, h-index, impact factor, research databases, research impact, research productivity, traditional metrics

INTRODUCTION

A peer-reviewed research paper serves as a platform to disseminate the results of a scientific investigation, creating an opportunity to expose the work publicly and for other scholars to assimilate the published knowledge.1 Using the study outcomes, other researchers can further validate, refute, or modify the hypotheses in developing their own research or clinical practice.2 In the academic and industry settings, researchers are highly encouraged to engage in scientific research and publish study results in a timely manner using the best possible platform. This “publish or perish” attitude drives research productivity, albeit with its own positive and negative consequences.

Essentially, the number of publications and the relevant impact thereof are widely regarded as measures of the qualification of a given researcher, and thus of his or her reputation. The same is valid and practiced for the reputation and standing of scientific journals. While the total number of publications alone may be used to derive the productivity of the researcher and their institution, it does not provide an indication of the quality and significance of a research publication, nor does it indicate the impact the research or the researcher has. Moreover, the reputation and standing of a researcher heavily depend on the impact the individual has had within his or her own research community or field of study. Thus, along with the growing number of publications, the question arises as to how a researcher's influence, standing and reputation, as well as research impact can be measured.

A quantitative measure indicates the value of an individual's research to their institution. As a measurable index of research impact, it can then be used as a form of assessment in granting research funds, awarding academic rank and tenure, in determining salaries and projecting annual research targets, as well as staff assessment and hiring new staff, for appropriate selection of examiners for doctoral students, or as selection of plenary or keynote speakers in scientific conferences. It is also a useful method for demonstrating return on investment to funding bodies, as well as to the host institution, industry, and the general public. A metric that offers the ability to identify key opinion-forming scientists in a particular area of research would also offer valuable knowledge for the development of 1) programs within academic and research institutions, and 2) policies in government agencies and relevant industries.3

Bibliometrics is the process of extracting measurable data through statistical analysis of published research studies and how the knowledge within a publication is used. The American psychologist and editor of Science, James McKeen Cattell, was responsible for introducing the concepts of scientometrics (the systematic measurement of science) and scientific merit, as well as quantity (productivity) and quality (performance) to measure science. In the early 1950s, bibliometrics was used by American psychologists as a method to systematically count their number of publications within their discipline, which laid a background for future pioneering metric work.4

Bibliometrics is one of the key methods to objectively measure the impact of scholarly publications while others include betweenness centrality (i.e., how often users or citations pass through the particular publication on their way to another publication from another one) and usage data (which includes Internet-based statistics such as number of views and downloads).5 The increase of data availability and computational advances in the last two decades has led to an overabundance of metrics, and indicators are being developed for different levels of research evaluation. The necessity to evaluate individual researchers, research groups, or institutions by means of bibliometric indicators has also increased dramatically. This can be attributed to the fact that the annual growth rate of scholarly publications has been increasing at exponential rates during the past four decades, leading to the so-called information overload or filter failure.

There are currently over two dozen widely circulated metrics in the publication world. These include, among others, the number of publications and citation counts, the h-index, Journal Impact Factor, the Eigenfactor, and article-level metrics. Such metrics can be used as a measure of the scholarly impact of individual investigators and institutions. An individual researcher's efforts can be quantified by these metrics where simple numbers can be substituted for the burdensome effort required to read and assess research quality.6 As a word of caution, metrics such as this bibliometrics do not, in fact, reflect in totality the importance of a given researcher to certain groups in the academic community. For instance, graduate and postgraduate students rely at large on book chapters to consolidate knowledge during their years of study. Hence, a researcher with many book chapter publications is providing an effective service to the academic community, albeit one that is not measured by current bibliometrics that is in place.

Many professionals in research are already aware of scientific metrics but are unfamiliar with its potential use in an academic setting, its impact on a researcher's career, and its significance in planning a career pathway or in evaluating performance within the academic society. Therefore, this paper aims to provide a brief overview of the most popular metrics currently in use in academia and research among the wide array of metrics available today. Using the lead author as an example, we intend to demonstrate how certain metrics may offer a different value for the same researcher, depending on the metrics or evaluation criteria employed. In addition, the goal of this paper is to raise the awareness of the scientific community about the emerging significance of bibliometrics as well as to describe the evaluation modalities that are currently available.

NUMBER OF RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS

Traditionally, the crucial yardstick by which the success of a researcher is assessed is the number of research papers he or she has published in a given field in peer-reviewed, Scopus or Institute of Scientific Information (ISI)-indexed, “high” impact journals. This straightforward bibliometric indicator is commonly used as a metric to evaluate and/or compare the research output and impact of individual researchers, research groups, or institutions. Conventionally, researchers with a large number of publications would be considered highly productive, experienced, and successful.

A researcher's number of publications can easily be retrieved from any major research database, such as PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, or ResearchGate. However, one has to keep in mind that the quantitative number generated for the same researcher may vary from one database to another. This is because certain databases include only specific types of articles such as original papers, reviews, letters, and commentaries but exclude other contributions such as book chapters, technical reports, and conference papers.

We ran a web-based search on the lead author and utilized the metrics obtained from popular databases to illustrate the possible diversity in search outcomes. As of November 18, 2015, Professor Ashok Agarwal has the following number of published research articles in these respective databases: 319 in PubMed, 515 in Scopus™, 313 in Web of Science®, more than 1500 in Google Scholar™, and 853 in ResearchGate. Based on this quantity, we may readily assume that Professor Agarwal is a highly successful scientist and an expert in his field. Given the diversity of these database search outcomes, however, it is apparent that to make such a claim about a researcher, other metrics would need to be used in conjunction with the number of publications. Moreover, the determination of the total number of scholarly publications alone is a measure of productivity rather than overall impact of a researcher.

Quality versus quantity has always been a sensitive subject in the academic world. One researcher may primarily publish review articles, which in itself may not require publication of individualized or original research. Conversely, a different researcher may have all his or her publications based upon original research only, amounting to a fewer number of articles published. Quantitatively speaking, the researcher who published review articles may be seen as a better, more productive researcher. However, to provide a more objective assessment that would lead to an unbiased conclusion, other types of metrics must be employed.

A different scenario for a comparative analysis involves an established researcher with more than 10 years of experience and over 50 publications versus a junior postdoctoral researcher with a few years of experience and fewer than 10 publications. The natural tendency would be for the senior scientist to be more highly regarded than the rising postdoctoral researcher. This is a common bias that occurs when focusing purely on the number of publications rather than the quality of the published research. Moreover, the number of publications metric does not reflect the quality of the journal in which these research articles are published, keeping in mind that some journals are less likely to reject a submitted manuscript than others.7

Research directors and prospective employers tend to scrutinize the impact factor of the journals in which a scientist is publishing and take this as a measure of the qualification and/or reputation of that scientist. However, a mere comparison of these numbers will not yield an objective evaluation as publications in generalized journals such as Nature or Cell garner more citations than do publications in a specialized journal for a very small scientific field. For a more balanced view of a researcher's performance, one has to compare the citations and journal impact factors of these publications within the specific field.

In summary, it is clear that the number of publications metric on its own serves as a poor tool to assess research productivity. Instead, it would be more appropriate to use this quantitative metric in conjunction with other types of metrics.

CITATION COUNTS

While the total number of publications metric may depict a researcher's efficiency or yield, it does not signify the actual influence or impact of those publications. The citation count metric represents the number of citations a publication has received and measures citations for either individual publications or sets of publications. Citation counts are regarded as an indicator of the global impact and influence of the author's research, i.e., the degree to which it has been useful to other researchers.8 The number of citations a scientific paper receives may depend on its subject and quality of research. Based on this assumption, citations have been used to measure and evaluate various aspects of scholarly work and research products.9,10

With the citation counts metric, the underlying assumption is that the number of times a publication has been cited by other researchers reflects the influence or impact of a specific publication on subsequent articles within the wider academic literature in a research area.11,12 Citation counts are widely used to evaluate and compare researchers, departments, and research institutions.13 However, similar to the number of publications, there is diversity between different databases for citation counts as well the number of publications as described above. For example, as of November 18, 2015, Professor Agarwal has 21,323 citations as documented by ResearchGate while on Google Scholar, his citation count is 32,252.

For the research scientist or research group, citation counts will show how many citations their papers have received over a selected time period and how the number of citations compares to that of other researchers or groups of researchers. It will also demonstrate the number of citations a particular journal article has received. Therefore, citation counts are considered as vital for evaluations and peer reviews. However, citation comparisons are only meaningful when comparing researchers in the same area of research and at similar stages in their career.

At times, an article that is “useful” may not always reflect its importance within a specified field. For example, important papers in a broader field such as cardiology would garner more citations than papers in a niche area such as infertility or assisted reproduction. Furthermore, there is no normalization done to account for the number of researchers within a specified field. This contributes to the reason why major journals within reproductive biology, fertility and assisted reproduction, and andrology such as Human Reproduction Update, Fertility and Sterility, Human Reproduction, and Asian Journal of Andrology have impact factors (2014) of 10.165, 4.590, 4.569, and 2.596, respectively, while the top journals in cardiology and cardiovascular medicine e.g., Journal of the American College of Cardiology, European Heart Journal, and Circulation have impact factors (2014) of 16.503, 15.203, and 14.430, respectively.

As with other metric parameters and bibliometrics in general, citation counts have numerous advantages and disadvantages. A common misconception held by many researchers and employers of this approach is that the citation count is an objective quantitative indicator of scientific success.13 However, the citation score of a researcher is not representative of the average quality of the articles published. In 2015, certain articles on popular topics in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology (AJOG) garnered more than 80 citations, respectively, which helped boost the impact factor of the journal. However, when these “outliers” were removed, the average quality of the articles published remained the same.

Another disadvantage of citation counts and several other metrics is that the subject field is not taken into consideration. The number of citations is heavily influenced by both the discipline and the time period used to collect the data.14 To reduce bias for both these factors, methods have been introduced to normalize the citation impact of papers.14,15 This can be done by focusing either on the cited reference or the citing article. Using the cited reference approach, the total number of times a specific publication has been cited is determined and then compared to a reference set, i.e., those publications from the same subject area and publication year. Alternatively, using the citing article approach, each citation is normalized according to subject and publication year.14

The original intent of a publication, which is to inform others of new scientific findings and further expand scientific knowledge, has been corrupted by a number of factors including (1) the exponential growth of journals and online journals and (2) adoption of journal metrics as a measure of scientific quality rather than written quality.16

While citation counts are thought to portray the quality of the articles published, there are several scenarios that can undermine this score. For example, citation counts of a researcher with high-performing co-authors, a small number of publications or a mediocre career may be skewed by one or two specific papers with high citations. Citation counts are also higher for researchers who mainly publish review articles that summarize other researchers’ original reports which are frequently cited in future articles. In addition, the citation count can be much larger for a more established researcher with many publications compared with a younger researcher with fewer publications.

Another source of bias is the unethical practice of conferring authorship without merit to a top ranking staff such as the department chairperson or director, or the head of the laboratory. However, this bias can be easily appreciated by evaluating whether an author publishes in a broad range of topics rather than in niche areas that denote the individual's expertise. In addition, studies have demonstrated that certain factors once present in a published paper may increase its citations. These include number of references (publications with higher number of references receives more citations),7 study design,17 data sharing,18 industry funding,19 mentorship,20 and mixed-gender authorship.21

Percentiles

The percentiles metric assesses the number or percentage of publications by a researcher or a research group that are in the top most cited publications in a particular country or globally.22 However, as different subject fields have different citation rates, the bias of field variation needs to be reduced. The best way to do this is to normalize the citation data as a percentile within its own specific field. This metric can be used to determine how many publications are in the top 1%, 5%, 10%, or 25% of the most-cited papers in the field. A single highly cited publication will have a much larger impact if it is used as part of a calculation of citation averages.

Open access tool

The term “open access” largely refers to published articles and other forms of scholarly communications being made freely available online to be accessed, downloaded, and read by internet users.23 Currently, about 15% of all research output have an open access status in journals and open archives. However, there are controversies surrounding the open access policy, particularly in the scientific merit and reliability of the published articles.

Many experts believe that the open access concept is at a disadvantage chiefly due to scientific papers that appear on the web without being subjected to any form of prior quality control or independent assessment. This is largely perpetrated by new online journals available chiefly to profit from the business of scientific publication. That being said, the open access publication concept does have a beneficial impact on researchers and academicians as well as the lay population, who may not be able to pay the article publication or access fee, respectively. De Bellis listed several additional benefits of the open access concept, such as faster publication and dissemination of new information, easier access for researchers and more importantly, ethical fulfillment of the public's right to know.24

Lawrence's study in Nature nearly 15 years ago, that showed a correlation between articles accessible freely online and higher citations,25 has since sparked a continuous debate on the impact of open access article availability on a researcher's productivity and that of an academic or research institution. The initial assumption has been that publications with open access are at an advantage as they tend to gain more citations and thus have a greater research impact26 than those with restricted access that require a subscription or impose an access fee.27 However, in their study, Craig et al. disputed these findings, citing methodological reasons for the positive outcome between open access publishing and higher citation counts. Instead, they proposed that the principal basis for the lifetime citations of a published research article is the quality, importance, and relevance of the reported work to other scholars in the same field. They suggested that while other factors may exert a moderate influence, it is not access that steers the scientific process - rather, it is discovery.23 Moreover, with time, as open access policies grow and become more commonplace, newer, more refined methods are also evolving to evaluate the impact of scientific communications.

Citation tools

Citation Map is a research tool by Web of Knowledge® that depicts citations using a map format, providing a dynamic representation of the impact that a document has on a field, a topic area, or trend. Its backward and forward citation feature lists citations in the current selected document, and documents that have cited the current selected document, respectively.12

Citation Report, another research tool by Web of Knowledge®, supplies a graphical representation and overview of a set of articles published and its citations for each year. It can be searched by topic, author, or publication name and be used to generate citation reports. The results detail information about (1) sum of times cited, (2) number of times cited without self-citations, (3) citing articles, (4) average citations per item, and (5) the h-index. This tool highlights the various trends of a topic, the publication trend of an author over time, and the most cited articles related to the chosen search topic.12

The Scopus™ tool, Citation Tracker, provides comprehensive information on searching, checking, and tracking citations. Citation Tracker can be used to obtain (1) a synopsis of the number of times a particular document has been cited upon its initial selection, (2) the number of documents that cited the selected document since 1996, and (3) the h-index. The information generated in the citation overview aids in the evaluation of research impact over a period.12

Google has a new tool called Google Scholar Citations that helps create a public profile for users including their citation metrics as calculated by Google. Google Scholar has a “cited by” feature which lists the number of times a document has been cited. At the conclusion of a search, the results show the number of times that both articles and documents have been cited, helping researchers get a preliminary idea of the articles and research that make an impact in a field of interest.

Normalized citation indicators

Normalized citation indicators attempt to counterbalance the biases introduced by traditional citation metrics and allow for fair comparison of universities or researchers active in different disciplines.28 The most commonly used method is the cited-side normalization method, where normalization is applied after computing the actual citation score.29 The citation value (observed) of a paper is compared with the expected discipline-specific world average (expected), which in turn is calculated by viewing papers published in the similar field, year, and document type. The comparison-ratio obtained indicates a relative citation impact above world average if above 1.30

An alternative method is the citing-side normalization of citation impact that accounts for the weighting of individual citations based on the citation environment of a citation.14 A citation from a field that encounters frequent citations receives a lower weighting than a field where citation is less common.

NUMBER OF DOWNLOADS

The electronic revolution in the scientific data arena has led to a growing amount of data and metadata that are easily accessible. These data can be utilized to monitor the usage factor of a publication, that is, the number of times a publication has been downloaded.31 While the download metric can be used as a supporting measure of a research impact, most databases may not provide these numbers readily to the user, whereas others may display this information on the publisher's page. Moreover, it is important to note that the numbers for the same researcher will fluctuate according to the different databases used. In addition, this particular measure may be biased as a more established researcher would tend to have a higher number of downloads than a lesser established scientist.

It is imperative to note, however, that the number of downloads of an article does not necessarily indicate quality rather it is indicative of interest on the subject matter. A broad or current “hot” topic may be highly downloaded while at the same time, it may just be an average work. Another point is that the number of downloads from personal and/or institutional repositories are difficult to track. In addition, given the variable policies of journals toward granting permission to post full texts in public repositories such as ResearchGate, the download metrics will also depend on the availability of full-texts in that particular repository. Although download metrics would certainly partially overcome digression related to the manner in which scientific publication is rated, the strict adoption of this metric will likely bias in favor of researchers publishing in open access journals.

As an example using the same author, the statistics displayed on ResearchGate states that Professor Dr. Ashok Agarwal has achieved 153,721 article downloads as of November 18, 2015. Of the 1498 publications (including books, chapters, and conference papers) listed as his total number of publications on the database on the same day, 346 (23%) publications lacked full-texts. Obviously then, the download of these publications will not be possible, therefore illustrating the shortcomings of the download metric.

h-index

One of the most prevalent metrics used nowadays is the h-index. This may be because some researchers have considered this index, among others, as the best measure of a scientist's research productivity.32 Introduced by Hirsch in 2005, the h-index is a metric that attempts to measure both the productivity as well as the broad impact of a published work of a scientist. As per Hirsch, the h-index of a researcher is calculated as the number of published papers by the researcher (n) that have each been cited at least n times by other papers.33 For example, if an individual researcher has published 20 articles and each has been cited 20 times or more, his or her h-index will be 20. Hirsch suggested that based on this index, individuals with values over 18 could be promoted to full professors, at least in the area of physics.

Hirsch has showed that his h-index gives a reliable assessment of the importance, significance, and comprehensive impact of a researcher's collective contributions. This metric also tries to capture the real-time output of a researcher, following the number of papers published as well as the impact connected to the number of citations in accordance with the underlying principle that a good researcher should have both high output and high impact. This metric is based on the principle that the accumulative scientific impact of two separate researchers with the same h-index should be comparable despite their number of publications or citation counts varying greatly. Taken from a different angle, in a group of scientists working in the same area of expertise and who are of the same scientific age with a similar number of publications or citation counts, the researcher with a higher h-index is likely to be a more accomplished scientist.33

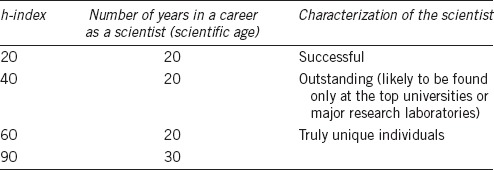

By potentially giving a baseline comparison of the number of citations that a given individual has compared to his or her peers, the h-index thereby can show his or her reputation in the scientific fraternity (Table 1). Citations are regarded as a measure of quality, with the conjecture that if a paper reports something important, other scientists will refer to it. Thus, the h-index works best when comparing researchers within the same discipline. The h-index has proven applicability to all areas of sciences and more recently to humanities and is seemingly robust against any outliers. Interestingly, this issue is driving more researchers to publish in open access journals. Moreover, the h-index uses a longer citation time frame than other similar metrics and thus attempts to capture the historic total content and impact of a journal. This in turn helps reduce possible distortions because the citations are averaged over more papers in total.

Table 1.

Generalizations of the h-index, according to Hirsch35

According to Patel et al., the h-index is the most reliable bibliometrics among healthcare researchers in the medical science field when compared among Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.34 We compared Professor Agarwal's h-index on November 11, 2015 on the following databases - Scopus (73), Web of Science (63), and Google Scholar (94) and found that the h-index was somewhat comparable between Scopus and Web of Science but clearly differed from Google Scholar.

However, the study also revealed several biases. Medical scientists with a physician status received a higher h-index than non-physicians with the comparable total number of publications and citations within Web of Science and Google Scholar.34 Similarly, North American scholars had a higher h-index than comparable scholars from European and other countries within Google Scholar. Of the three databases, a higher h-index was found for younger-aged (based on birth year) medical scientists.34 As with any metric, caution for biases should be used in evaluating and comparing a scientist's impact in any given field.

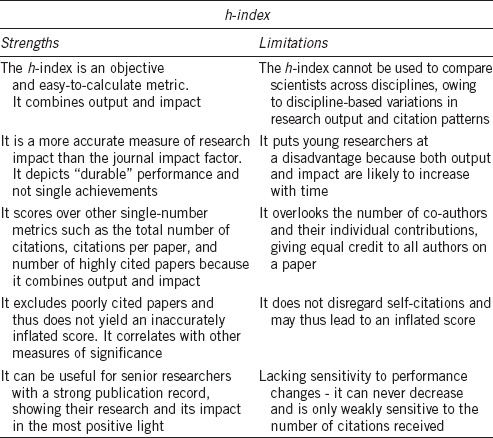

The strengths and limitations of the h-index are highlighted in Table 2. Criticism of the h-index includes that it represents a one-size fits all view of scientific impact.11 The h-index is also discipline-size dependent in that individuals in highly specialized, small fields have lower h-indices. The h-index also increases according to academic rank.35 This may be because the h-index is related to the amount of time spent in a discipline, i.e., a shorter career results in a lower number of citations leading to a lower h-index. In addition, the h-index does not discriminate between first authorship and co-authorship and self-citations.36 It also fails to distinguish the relative contributions to the work in multi-author papers. In other words, the h-index does not take into account whether an author is the first, second, or last author of a paper although these positions have a higher value placed upon them compared to the other intermediate author positions.

Table 2.

Strengths and limitations of the h-index

Recently, the predictive power of the h-index was questioned as it contains intrinsic autocorrelation, thereby resulting in a significant overestimation.37 Furthermore, the numbers cannot be compared across research disciplines or even within different fields of the same discipline because citation habits differ. As such, there have been attempts made to normalize the h-index across disciplines. The g-index aims to improve its predecessor by giving more weight to highly cited articles.38 The e-index strives to differentiate between scientists with similar h-indices with different citation patterns.39 The assessment of a constant level of academic activity can be achieved using the contemporary h-index which gives more weight to recent articles.40 The age-weighted citation rate (AWCR) adjusts for the age of each paper by dividing the number of citations of a given paper by the age of that paper. The AW-index is obtained from the square root of the AWCR, and may be used to compare against the h-index.41 The multi-authored h-index modifies the original metric by taking into account shared authorship of articles. Despite all improvements on the initial h-index, the original metric is still the most widely used.

A new bibliometrics, Bh index, reported by Bharathi in December 2013, proposes to be an enhanced version of the h-index by resolving the difference between the young scientist with few but significant publications (highly cited) and the mature scientist with many yet less impactful (less cited) publications. The Bh index evaluates the researcher based on the number of publications and citations counts using the h-index as the base and a threshold value for a selection of articles known as the “h-core articles.” On the Bh index, in a comparison of two scientists with the same number of publications and same citation count, the one with a more homogenous increase in citation counts will have a higher score than the scientist with citations skewed toward a few publication.41 This method may have resolved one critical aspect of the h-index but does not address other issues such as citation behaviors, self-citations, order of authors, and number of authors.

JOURNAL IMPACT FACTOR

In 1955, Eugene Garfield created a bibliometric index, the Impact Factor, which was meant to be used by librarians to evaluate the quality and influence of journals. The impact factor was then designed by Eugene Garfield and Irving Sher for corporate use from 1961 as a simple method to select journals for the Science Citation Index (SCI) regardless of their size. SCI is a multidisciplinary database in science and technology of the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) founded by Garfield in 1960 and acquired in 1992 by Thomson Reuters. The Journal Impact Factor (JIF) developed by Thomson Reuters in 1995 is a good indicator of both the quality and influence of a journal.42,43,44

The reputation of a scientific journal dominates the publication choice by researchers and it is mainly determined by this Impact Factor (also called ISI Impact Factor) - a metric that reflects how frequently the totality of a journal's recent papers is cited in other journals. Based on the Web of Science citation index database, it compares the citation impact of one journal with another. The Impact Factor analyzes the average number of citations received per paper published in a specific journal during the preceding 2 years.44,45

When calculating an Impact Factor, the numerator represents the total number of citations in the current year to any article published in a journal in the previous 2 years whereas the denominator is the total number of articles published in the same 2 years in a given journal. Therefore, Impact Factor (2015) = (citations 2013 + citations 2014)/(articles 2013 + articles 2014).36 As an example, if the journal has an Impact Factor of 1.0, it means that on average, the articles published 1 or 2 years have been cited 1 time.

Citing articles may be from the same journal; however, most citing articles are from different journals.12 In terms of citations, original articles, reviews, letters to the editor, reports, and editorials are also counted. Furthermore, only citations within a 2-year time frame are considered. However, different fields exhibit variable citation patterns - the health sciences field, for example, receives most of their citations soon after publication whereas others such as social sciences do not gather most of their citations within 2 years. This diminishes the true impact of papers that are cited later than the 2-year window. The arbitrary past 2 years-based calculation taken together with the inclusion of non-original research citations renders it not very accurate and comparable but rather biased for different disciplines.

The journal impact factor scores vary by field and are themselves skewed within a field. Following the well-known 80-20 rule, the top 20% articles in a journal receive 80% of the journal's total citations. The Impact Factor metrics were not intended to make comparisons across disciplines because every discipline has a different size and different citation behavior - mathematicians tend to cite less while biologists tend to cite more.48 For example, in the cell science category, Cell (journal) has an Impact Factor of 32.242 whereas in mathematics, Acta Mathematica has an IF of 2.469, but both have a good citation index in their disciplines.

In disciplines such as anatomy or mathematics, papers tend to live longer compared to articles that are rather short-lived in biochemistry or molecular biology.49 Therefore, the impact factor needs to be seen in the context of different disciplines. For example, the impact factor for the most influential journal in oncology (CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, IF (2014) = 144.80) differs significantly from that of the most influential journal in reproductive biology (Human Reproduction Update, IF (2014) = 10.165). Another major setback of this metric is that even in the journals with the highest impact factors, some papers are never cited by other researchers while others are cited inappropriately. It would be ideal if the authors selected a journal that is not only relevant to the subject and scope of the manuscript but also on the impact of the journal in its area of research instead of purely on the basis of the Journal Impact Factor metrics.49

In addition, within wider areas of research such as Biology, for example, certain disciplines are more intensely cited than others and therefore, will produce a higher impact factor due to the time-dependent interest in that particular area of research. To illustrate this point, if a given article within the area of immunology is published in the Annual Review of Immunology, it would have an Impact Factor 39.327 while an equivalent article published in the Annual Review of Anthropology would only have an Impact Factor of 2.717. This large difference in impact factors is seen despite both journals belonging to the same editorial group and having the similar standards for article submission.

The Impact Factor has evolved from its initially intended use to evaluate the quality and impact of scientific journals to the use or rather abuse of the evaluation and measurement of scientific standing of individual researchers (by how often they publish in high impact factor journals), institutions and countries - a purpose which the Impact Factor was not designed and meant for. The policy of using the Impact Factor to rank researchers ignores Garfield's own recommendation on the subject, which is to instead use actual citation counts for individual articles and authors for this purpose.50 Moreover, institutions also abuse the Impact Factor for the evaluation of research quality when recruiting or making tenure decisions. This abuse even prompted Garfield to warn that the Impact Factor should not be used as a surrogate for the evaluation of scientists.51 This dominant trend significantly adds to the massive criticism aimed at the Impact Factor.52,53

Manipulation of journal impact factor is not unheard of in the world of research evaluation. There are several ways to artificially inflate the impact factor of a journal, such as publishing more review papers and fewer letters to the editor and case reports which are infrequently cited.54 Another option would be to not accept papers with lower chances of citation, such as those that are on a topic which is very specific despite it being a good article on its own. Based on the past incidences, editors have tried to boost the performance of their journal either by unethical requests to the authors to cite unrelated papers out of the journal or by the questionable attempt to publish annual editorial referencing.55,56 These attempts to manipulate the impact of a journal will eventually lead not only to a damaged reputation of the journal but also of the editor.

While there is no question that acceptance of a paper by a prestigious journal must be taken into consideration (prestigious journals do have high impact factors, as the two tend to go together), it is definitely not synonymous with citations as demonstrated by applying the concept of positive predictive value (PPV), which measures the probability of a “positive result” being the reflex of the underlying condition being tested. In a recent study, PPV was calculated within three IF classes that were arbitrarily defined as HIGH (IF ≥ 3.9), MID (2.6 ≤ IF < 3.9), and LOW (1.3 ≤ IF < 2.6). PPV was determined as follows: an article published in a journal within a given classification class was deemed a True Positive if it was granted N cites/year, N being comprised within the class boundaries; it was deemed a False Positive if this condition was not met. Although PPV was higher in the “HIGH” class (PPV = 0.43) than with “MID” and “LOW” classes (PPV = 0.23–0.27), 57% of the articles published in high IF journals were false-positives, i.e., had fewer than 3.9 citations/year. In contrast, 33% and 27% of the articles published in “LOW” and “MID” impact classes, respectively, achieved higher citation numbers than expected for that particular class and, therefore, were downgraded. Interestingly enough, 15% of the articles published in the “LOW” impact class belonged to the “HIGH” class according to the number of citations. This outcome exposes the flawed characteristic of the journal impact factor evaluation.57

The Impact Factor metrics is obviously beneficial in the context of research evaluation58,59 and is a useful tool for bibliometric analysis. However, the Impact Factor is not a straightforward substitute for scientific quality, but when correctly used is an excellent tool in the bibliometric toolbox, which can highlight certain aspects of a research group's performance with regards to the publication process.

The audience factor

Since the Journal Impact Factor is prone to bias, several modifications of this metric have been introduced to normalize the data collected using both citing-sided and cited-sided algorithms.14,60 Cite-sided normalization is calculated as the ratio of a journal's citation impact per article and the world citation average in the subject field of that journal. It compares the number of citations of an article with the number of citations of similar publications in the same year and field. Citing-side normalization involves counting the total number of citations of a paper and then comparing that to the citation count for similar publications in the same subject field and the same year. The audience factor normalizes for the citing-side and is based on calculating the citing propensity (or the citation potential) of journals for a given cited journal categorizing by subject field and the year of publication. This is then fractionally weighted within the citation environment.60 Thus, if a citation occurs in a subject field where citations are infrequent, the citation is given a higher weighting than if the citation was cited in a field where citations are common. This audience factor is based on the citing journal rather than the citing article.

EIGENFACTOR™ METRICS

The Eigenfactor Metrics consists of two scores such as Eigenfactor™ Score and Article Influence™ Score. The Eigenfactor Metrics aims to extract maximum information to improve evaluations of scholarly archives. Both these new key metrics are calculated using the Eigenfactor Algorithm.13 To put it plainly, the Eigenfactor™ score measures “importance” whereas the Article Influence Score measures “prestige.” A point to note is that unlike the standard impact factor metrics, the Eigenfactor Metrics does not include self-citations.

Eigenfactor™ Score

The Eigenfactor™ Score is a fairly new alternative approach to the Journal Impact Factor. Similar to the Journal Impact Factor, the Eigenfactor™ Score is essentially a ratio of the number of citations to the total number of articles. It is based on a full structure of the scholarly citation network where citations from top journals carry a greater weight than citations from low-tier journals. The Eigenfactor™ Score describes what the total value of a journal is based on and how often a researcher is directed to any article within the specified journal by following citation chains.13 In other words, the Eigenfactor™ Score is basically a measure of how many people read a journal and think its contents are important.

The Eigenfactor™ Score is an additive score and is measured indirectly by counting the total number of citations the journal or group of journals receives over a 5 years period. The Eigenfactor® Score improves on the regular Impact Factor because it weighs the citation depending on the quality of the citing journal, which is why the Impact Factor of a journal is considered in this new metric. However, unlike the Journal Impact Factor, the Eigenfactor™ Score counts the citations to journals in both the sciences and social sciences, eliminates self-citations, and randomly determines the weight of each reference according to the amount of time researchers spend reading the journal.

Many biases can accumulate with this metric, including comparisons between new researchers and established ones. As discussed previously regarding Impact Factor, articles with high citation numbers published in low- or mid-impact factor journals are downgraded and may suffer a double penalty for their wrongful choice of a journal. This relates to the known tendency of citation granters to favor citing top rather than not-quite-so-top journals. Thus, the Eigenfactor™ Score must be used in combination with other metrics.

Article influence score

The Article Influence Score measures the influence, per article, of a particular journal. As such, this new score can be compared directly to the Thomson Reuters’ Impact Factor metric. To calculate the Article Influence Score, a given journal's Eigenfactor™ Score is divided by the number of articles in that journal, then normalized in order for the average article in the Journal Citation Reports to have an Article Influence Score of 1.13 A score >1.00 indicates that each article in the journal has an above-average influence whereas a score <1.00 shows that each article has below-average influence.

SCImago Journal Rank

While the Eigenfactor™ Score measures the total number of citations received over a 5 years period, the SCImago Journal Rank and source normalized impact per paper (SNIP) use a shorter time frame of 3 years. SCImago Journal Rank is a size-independent metric that is similar to the Eigenfactor™, but it places more emphasis on the value of publishing in top-rated journals than on the number of citations of a publication.61 The algorithm used to obtain this impact factor allocates higher values to citations in higher ranking journals. In addition to the quality and reputation of the journal that a publication is cited in, the value of the citation also depends on the subject field. This metric is useful for journal comparison as it ranks them according to their average prestige per article.

Impact per Publication (IPP)

This metric was developed by Leiden University's Centre for Science and Technology Studies.62 It is the ratio of citations per article published in a specific journal over a specific period. It is measured by calculating the ratio of citations in 1 year to articles published in the 3 previous years divided by the number of articles published in those same 3 years. The chance of manipulation is minimized as only the same publications are used in the numerator and denominator of the equation, making it a fair measurement of the journal's impact. IPP does not use the subject field and only gives a raw indication of the average number of citations a publication published in the journal is likely to receive.

Source normalized impact per paper (SNIP)

SNIP measures a journal's contextual citation impact by considering the subject field, how well the database covers the literature in the field and how often authors cite other papers in their reference lists.62 SNIP is an IPP that has been normalized for the subject field. SNIP normalizes for the citation rate subject differences by measuring the ratio of a journal's citation number per paper to the citation potential in its subject area. This allows researchers and institutions to rank and compare journals between different subject areas. It is particularly useful for those working in multidisciplinary fields of research.

ORDER OF AUTHORS

Authors are generally classified as primary, contributing, senior, or supervisory with the possibility of having multiple roles. Normally, the primary author contributes the most amount of work to the article and writes most of the manuscript whereas the co-authors provide essential intellectual input, may contribute data and shape the writing of the manuscript, and participate in editing and review of the manuscript. Thus, the order of authors within a specific publication can be regarded as important, depending on the experience level of a researcher.63

The author sequence gives insight into the accountability and allocation of credit depending on manuscript authorship and author placement. The relationship between the author's position in the author list and the contribution reported by the author were studied in multi-authored publications. It was found that the first author had the greatest contribution to a particular article and that the existing arrangement of author order and contribution proposed a constant theme.63 Other studies have concurred that the first author position in multi-authored papers is always considered as that of the person who made the greatest contributions.64,65,66

In the biomedical sciences, the last author often acquires as much recognition as the first author because he or she is assumed to be the intellectual and financial driving force behind the research. Moreover, the author's position in a paper is an important bibliometric tool because evaluation committees and funding bodies often take the last authorship position as a sign of successful group leadership and make this a criterion for hiring, granting, and promotion purposes. Other proposed approaches in the evaluation of authors in multi-authored papers are, namely, sequence determines credit (declining importance of contribution), first–last author emphasis, author percent contribution indicated, and equal author contribution (alphabetical sequence).66

In actuality, it is difficult to determine the exact amount of work that each author has contributed on a paper. Thus, the normalization of the position of an author within a research paper is much needed as it is not equivalent being the second of 2 authors compared to the second out of 6 authors on an article. Ideally, the ranking should correspond objectively to the amount of work that has been put in by each author, as the time and effort that are required to write a clinical paper with 2000 patients and 10 authors would not match one with 10 patients and 5 authors. Perhaps, as recommended by Baerlocher's group, the method applied to evaluate each contributor on a research paper should be clearly indicated along with a quantitative assessment of the authors’ rank in that publication. This would prevent any misconceptions and subjective distribution of author contributions.63

Such evaluation measures can be important in determining the number of times an individual was a primary or contributing author. Consequently, an individual who has authored multiple articles with a role as a primary author will be regarded more highly than an author with more articles with a role as a contributing author. This is primarily important in an academic setting where the authorship sequence would make a greater difference to young scientists who are initiating their research career compared to an established senior or tenured scientist. Although the author order is not a large metric used by assessors, it is still important and can provide insight into the input of a researcher.

Despite the clear authorship definition issued by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), numerous issues (including ethical concerns) have arisen regarding authorship attribution. One form, gift authorship, is conferred out of respect for or gratitude to an individual. For example, in Asian and Latin America cultures, departmental heads or senior researchers may be added to a paper regardless of their involvement in the research. Another form, guest authorship, may be used for multiple purposes to increase the apparent quality of a paper by adding a well-known name or to conceal a paper's industry ties by including an academic author, for example. Finally, coercive authorship typically consists of a senior researcher “forcing” a junior researcher to include the name of a gift or guest author. Among these, gift (also known as honorary) authorship is of major concern as it was found in approximately 18% of the articles published in six medical journals with a high impact factor in 2008. The prevalence of honorary authorship was 25.0% in original research reports, 15.0% in reviews, and 11.2% in editorials.67

ARTICLE-LEVEL METRICS

Of late, the inclusion of social media (usage and online comments) to biometrics is quickly gaining popularity and recognition in the world of metrics.68 As online medical communication and wireless technology advances, it has been proposed that the impact of a research paper be evaluated by alternative metrics that quantitatively assess the visibility of scholarly information. This may be executed by tallying the number of hits and citations on the Internet, downloads, mentions in tweets and likes of research communications by social media platforms, blogs, and newspapers.69

Aggregation of article-level metrics (ALM) is inclusive of traditional metrics that are journal citations-based. It consists of data sources and social media content such as article usage, citations, captures, social media, and mentions. This complementary combination of ALM metrics thus provides a more wholesome view of scholarly output with the benefit of immediate availability and real-time assessment of its social impact. The examples of ALM are Altmetric, Plum Analytics, ImpactStory, and Public Library of Science-Article-Level Metrics.70

Altmetric

Altmetric, an online service (www.altmetric.com) that allows the tracking of how much exposure an article has had in the media, is gaining popularity. Launched in 2011, Altmetric is supported by Macmillan Science and Education, which owns Nature Publishing Group. The rationale behind the use of Altmetric is that mentions of a publication in social media sites can be counted as citations and should be taken into account when reviewing the impact of research, individual, or institution.71

The Altmetric score is based on the quantitative measure of the attention that a scholarly article has received. There are three main factors used to calculate the Altmetric score which is volume, sources, and authors. This metric quantifies how many times a specific article has appeared in newspapers or blogs, or even how many times it has been mentioned in tweets on the popular social media platform Twitter or Facebook, by generating a quantitative score. These mentions are rated by an order of importance such that a mention in a newspaper is greater than a tweet.13

Since blogs and social media platforms are driven by and maintained by end-users, social media metrics can be artificially inflated if the article becomes viral with the lay public. Although it has its own potential, this metric must be taken with caution and may not necessarily reflect the true importance of an article. Nonetheless, social media metrics is in fact not a scientific method to measure the quality of an article. It instead measures the penetrance of an article for lean readers, which is unrelated to the main purpose of the traditional metrics that aim to measure the scientific quality of a published article.

Other feasible measures to indicate and evaluate the social impact of research include media appearances, community engagement activities, book reviews by experts within the same field, book sales, number of libraries holding a copy of the publication, citations by nontraditional sources (internal government reports, etc.), and unpublished evidence of the use of a specific publication by community groups or nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).6

Academic networks

Academic networks such as ResearchGate.net (https://www.researchgate.net) and Academia.edu (https://www.academia.edu) are another type of ALM tool. Authors can use these platforms to share different types of scholarly output and scientific publications, provided that they are not subject to copyright restrictions. These networks also provide metrics that complement traditional metrics in analyzing the impact of publications.70] For example, ResearchGate tracks the number of publication views (reads) and downloads, citations and impact points along with the researcher profile views. It also awards each researcher with impact points and an RG score that is based on their scientific publications available in their profile and how other researchers interact with these scholarly outputs. For example, Professor Agarwal has a calculated RG Score of 51.79, which is higher than 98% of most members. Researchers can self-archive their scientific publications and related material, and thus have a control over the amount of their research work that is visible to other researchers.

F1000Prime

F1000Prime (http://f1000.com/prime) is a biology and medical research publications and database comprising publications that are selected by a peer-nominated group of world-renowned international scientists and clinicians.72 In this database, the papers are rated and their importance is explained. The recommendations from this database can be used to identify important publications in biology and medical research. The database was launched in 2002 and initially had over 1000 Faculty members. This has now grown to more than 5000. Faculty Members and article recommendations span over 40 subject areas which are further subdivided into over 300 Sections. The Faculty contributes approximately 1500 new recommendations per month. The database contains more than 100 000 records and aims to identify the best in international research.

Mendeley

Mendeley (https://www.mendeley.com) was developed in 2007 to manage and share research papers, research data and facilitate online collaborations.73 It uses an integrated desktop and web program. The program was acquired by Elsevier in 2013, which many in the scientific community considered a conflict of interest in opposition to the open access model of Mendeley.74

DATABASES

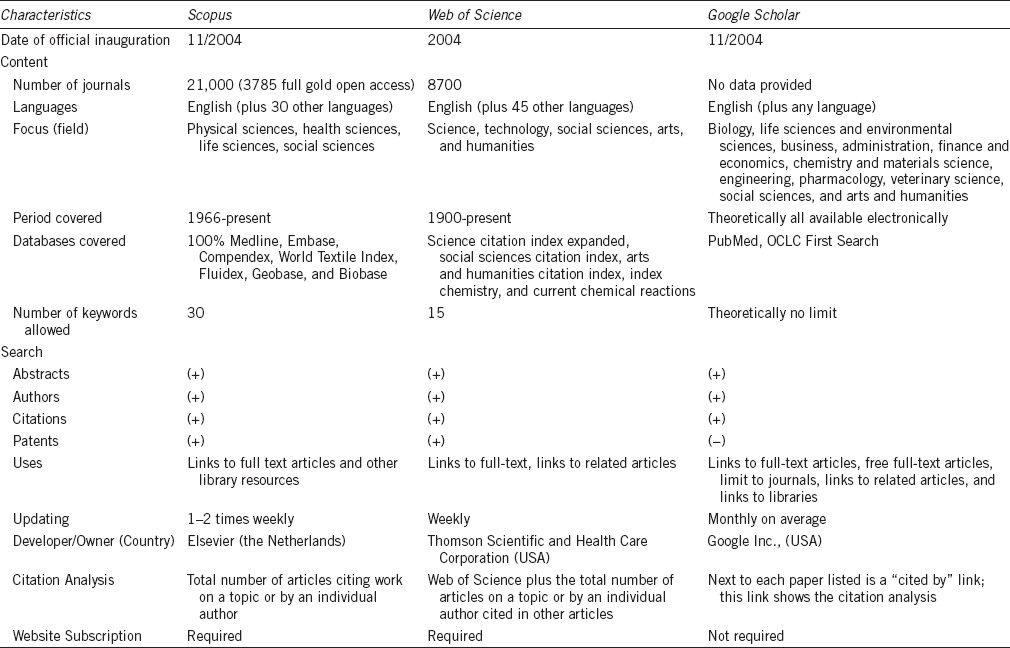

Databases aggregate citations and some databases have created their own bibliometric measures. Elsevier (Scopus) and Thomson Reuters (Web of Science), the chief competitors, use their own unique data, journals, publications, authority files, indexes, and subject categories. They provide their data to labs to create new metrics that are freely available online but are also available as a subscription. Of the three databases, Google Scholar is the only online citation database free to the public. Its database cites a global collection of multidisciplinary books, journals, and data but is limited to e-publications. A comparison of specific characteristics of the three most popular databases such as Scopus (http://www.scopus.com), Web of Science (http://login.webofknowledge.com), and Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com) is shown in Table 3. No database would be able to list all publications; even these main three sources vary substantially in content. A combination of databases may, therefore, balance out the shortcomings of any one alone.

Table 3.

Comparison among characteristics of the Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases

Scopus

Launched in late November 2004, Scopus, owned by Elsevier, is the largest abstract and citation database containing both peer-reviewed research literature and as well as web sources. Scopus is a subscription-based service and provides the most comprehensive overview of the world's research output in the fields of Science, Technology, Medicine, Social Sciences, and Arts and Humanities. Scopus also covers titles from all geographical regions. Non-English titles are included as long as English abstracts are provided with the articles.

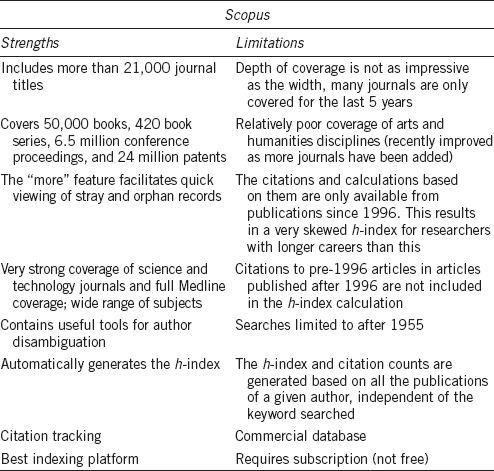

The strengths and limitations of the Scopus database are shown in Table 4. Journal coverage in Scopus is more comprehensive than in Web of Science.16 Scopus can match author names to a certain degree of accuracy because authors are always matched to their affiliations. However, the citation data for all disciplines in the Scopus database extend back to 1996 only, and thus the impact of established researchers would be undervalued. Scopus calculates the h-index for particular authors but requires a paid subscription.

Table 4.

Strengths and limitations of the Scopus database

Web of Science

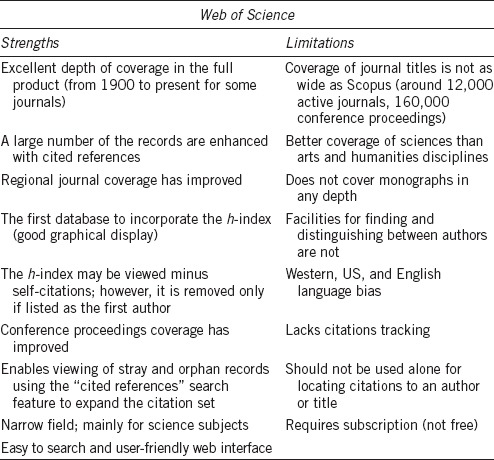

Thomson Reuters’ Web of Science (WoS, formerly known as Web of Knowledge) is a collection of 7 online subscription-based index databases of citations to a multidisciplinary collection of scientific works (such as books, journals, proceedings, patents, and data). Web of Science can be extremely useful to procure an indicator of citation rates but does not provide a completely accurate list of information for a quick comparison. One major limitation with Web of Science is that it is a per institution, subscription-based service.

Other strengths and weaknesses of the Web of Science database are shown in Table 5. This database also has a select but limited scope of publications. Web of Science includes only the initials of the author's first name, such that Jane Smith, John Smith, and Jorge Smith are all identified as “Smith-J.” In addition, it does not contain any information on the relation between the names of the authors and their institutional addresses. For example, in retrieving papers by “Doe-J” who is affiliated with XYZ University, a paper co-authored by “Doe-J” of ABC University would also be selected. Web of Science automatically calculates the h-index for publications, accounting only items listed in Web of Science, so books and articles in non-covered journals are excluded. The h-index factor is based on the depth (number of years) of a Web of Science subscription in combination with a selected timespan. Publications that do not appear on the search results page will not be included in the calculation. If a subscription depth is 10 years, the resulting h-index value will be based precisely on this depth even though a particular author may have published articles more than 10 years ago.

Table 5.

Strengths and limitations of the Web of Science database

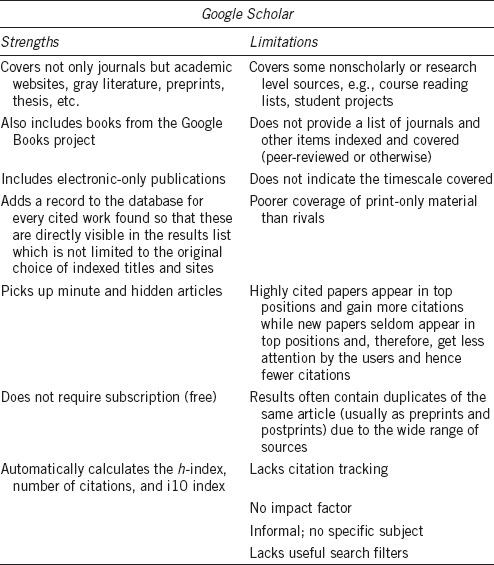

Google Scholar

Google Scholar is an online, freely accessible search engine. It searches a wide variety of sources including academic publishers, universities, and preprint depositories. Peer-reviewed articles, theses, books, book chapters, technical reports, and abstracts can be searched on this database. A critical factor in using Google Scholar is that in many cases, it indexes the names of only the first and last authors.

The strengths and weaknesses of the Google Scholar database are shown in Table 6. Google Scholar may not totally capture articles in languages other than English (so-called LOTE articles) and citations in chapters and books and, therefore, it may underestimate h-indices. Google Scholar is probably more inclusive than ISI's Web of Science and, thus, it may result in a better h-index calculation. Despite these caveats, comparison of h-indices obtained with Google Scholar and Scopus correlate highly.35

Table 6.

Strengths and limitations of the Google Scholar database

AUTHOR RANK

The author rank refers to the comparative standing of each author in a particular focus area of research or profession from the highest to lowest position. The author order can be determined using various databases; however, the metrics generated differs from database to database. To illustrate this, we searched both the Scopus and Web of Science databases using several keywords, including varicocele that is the subject of this Special Issue of Asian Journal of Andrology. Based on the results obtained from Scopus, we ranked the 10 most cited authors for each keyword search in a decreasing order. For each keyword search on the Scopus database, the search was done on November 11, 2015, and the search field used was “All Fields,” in the subject areas of “Life Sciences” and “Health Sciences,” document types “All” and years published “All Years to Present.”

We then compared the Scopus results against the 10 most cited authors for the same keyword on Web of Science. If a single researcher had multiple profiles in Web of Science, the profiles were combined to obtain a total single result for each category. Supplementary Tables 1 (364KB, tif) –4 (289.6KB, tif) show the results generated from both databases using the following keywords: (1) Andrology, (2) Male Infertility, (3) Varicocele, and (4) Assisted Reproduction. Following this, we did a search combining the keywords (1) Andrology OR Male Infertility (Supplementary Table 5 (316.7KB, tif) ) and (2) Male Infertility AND Varicocele (Supplementary Table 6 (288.7KB, tif) ). We also noted the total number of documents generated along with the citation counts and h-index of each author ranked in the respective top 10, based on each keyword search results.

Search results for the 10 most cited authors using the keyword “Andrology” generated using Scopus and Web of Science. The sequence is set according to the number of publications found on Scopus (as of November 11, 2015)

Search results for the 10 most cited authors using the keyword “Male Infertility” generated using Scopus and Web of Science. The sequence is set according to the number of publications found on Scopus (as of November 11, 2015)

Search results for the 10 most cited authors using the keyword “Varicocele” generated using Scopus and Web of Science. The sequence is set according to the number of publications found on Scopus (as of November 11, 2015)

Search results for the 10 most cited authors using the keyword “Assisted Reproduction” generated using Scopus and Web of Science. The sequence is set according to the number of publications found on Scopus (as of November 11, 2015)

Search results for the 10 most cited authors using the keyword “Andrology OR Male Infertility” generated using Scopus and Web of Science. The sequence is set according to the number of publications found on Scopus (as of November 11, 2015)

Search results for the 10 most cited authors using the keyword “Male infertility and varicocele” generated using Scopus and Web of Science. The sequence is set according to the number of publications found on Scopus (as of November 11, 2015)

The total number of documents for the keyword “Andrology” differed between Scopus and Web of Science. This illustrates that the type of metrics will influence how a given researcher will be ranked. The greatest discrepancy was in the number of documents retrieved from the keyword search for “Andrology” (Supplementary Table 1 (364KB, tif) ) while similar results were obtained for the combined keyword search of “Male Infertility AND Varicocele” retrieved from both databases (Supplementary Table 6 (288.7KB, tif) ). These differences could be due to the different depth and other characteristics of publication coverage in both databases.

For the search word “Andrology,” the authors who were the top 2 in the Scopus search were the same as those in the Web of Science search (Supplementary Table 1 (364KB, tif) ). The top 3 authors in the single keyword searches such as “Male Infertility” (Supplementary Table 2 (303.2KB, tif) ), “Varicocele” (Supplementary Table 3 (289.6KB, tif) ) as well as the combined searches “Andrology OR Male Infertility” (Supplementary Table 5 (316.7KB, tif) ), and “Male Infertility AND Varicocele” (Supplementary Table 6 (288.7KB, tif) ) were the same when searched with both databases. The top 5 authors were similar for the keyword “Assisted Reproduction” in both databases, respectively Supplementary Table 4 (289.6KB, tif) . For all the top authors for each keyword, their citation counts and h-index varied between the databases.

We previously noted that the citation counts and h-index generated using Scopus was based on all the publications of the given author and did not depend on the keyword searched. However, the h-index generated using Web of Science was based on the number and citation counts of only the publications that corresponded to the keyword searched. For example, Professor Agarwal's citation counts and h-index generated on Scopus was 18,329 and 73, respectively, regardless of the keyword searched. However, his h-index differed according to the keyword searched on Web of Science: 16 (andrology; Supplementary Table 1 (364KB, tif) ), 61 (male infertility, Supplementary Table 2 (303.2KB, tif) ), 31 (varicocele, Supplementary Table 3 (289.6KB, tif) ), 30 (assisted reproduction, Supplementary Table 4 (289.6KB, tif) ), 62 (andrology OR male infertility, Supplementary Table 5 (316.7KB, tif) ), and 31 (male infertility AND varicocele, Supplementary Table 6 (288.7KB, tif) ). Although using Web of Science, his h-index was similar for the searches “varicocele” and “male infertility AND varicocele,” the number of publications retrieved and the citation counts were 92 and 3482 (varicocele, Supplementary Table 3 (289.6KB, tif) ), and 78 and 3434 (male infertility AND varicocele, Supplementary Table 6 (288.7KB, tif) ), respectively.

Based on the results obtained from the searches on both major databases, Professor Agarwal is ranked as a top author in the fields of male infertility and varicocele (as of November 11, 2015). However, for a more objective assessment of the ranking of key scientists in a given research area, the citation counts and h-index of the author should also be considered. Discrepancies between databases in ranking of authors may be due to the considerable differences in the research database content that does not encompass the entire list of scholarly publications contributed by each researcher. These metrics can be used in combination with others to acquire a general impression of a researcher's establishment or success in a particular field.

USEFULNESS OF BIBLIOMETRICS

Bibliometrics plays an important role in ranking the performance of a researcher, research groups, institutions, or journals within the international arena. Individual researchers may use this information to promote their research and to develop a more meaningful curriculum vitae to help their career. It may also helpful in determining the value of their research contributions to the future direction of research in a particular institution, depending on whether they have a higher or lower impact score. These tools may also facilitate recruitment and promotion practice for universities, government institutions, and privately funded laboratories.

For the individual scientist, bibliometrics is a useful tool for determining the highest impact journals to publish in. From a student's perspective, it helps them determine the most important papers on a topic and find the most important journals in a field. It also helps identify leading researchers and articles in a particular field. Research impact tracks the development of a research field and is helpful in identifying influential and highly cited papers, researchers, or research groups. In this way, researchers can identify potential collaborators or competitors in their subject area. Impact factors can be helpful in countries where there is limited access to competent experts in a subject field required for peer review.

Research performance is a key in decision making for funding and is especially useful when those who are making the decisions are not experts in the field. Bibliometric information about a researcher or an institution's productivity can be used by funding bodies to determine which projects are more worthy of funding and likely to give more return on investment. Furthermore, it may helpful in the distribution of funds when budgets are limited. Government officials must make similar decisions while weighing national research needs for choosing what should be supported or which research projects and researchers should receive more support than others. Policymakers, research directors, and administrators often use this information for strategic planning and keeping the general public informed about state-of-the-art research.

LIMITATIONS OF TRADITIONAL BIBLIOMETRIC TOOLS

Bibliometrics is a quantitative assessment that compares the citation impact of researchers, research groups, and institutions with each other within specific disciplines and periods. When looking at bibliometrics, researchers should only be compared to those in a similar field and at a similar stage in their career as publications and citations can vary widely between disciplines and with increasing experience. Such bias works very much in favor of the established scientist. Likewise, the standing of a research institution can only be compared to an institution of a similar size.

It is important to recognize that global rankings determined by bibliometrics may be based on inaccurate data and arbitrary indicators. Metrics is thwarted with a plethora of ambiguities, error, and uncertainties so they must be used with caution. Author names and institution names must be clarified to compute meaningful bibliometric indicators for research evaluation.74 Another problem is honorary authorship and ghost authorship which lists individuals as authors who do not meet authorship criteria that unfairly increases the productivity of a researcher.75

This paper demonstrates that not all publications or research areas are included in all methods for gathering data; hence, different results will be obtained depending on which data collection method is implemented. Each bibliometric tool will differ according to the content covered, the discipline and depth of coverage. No single metric will allow anyone to fully evaluate a researcher's impact. It is even much more difficult to predict a scientist's future impact because of the current flaws in the model.37

It is essential to use the appropriate tool for evaluation. Metrics is often used by people who have no practical knowledge of how to use them and how to interpret the results within its context. Furthermore, a researcher's interests and academic achievements may conflict with the research priorities or the goals of the institution, funding bodies, and policy makers. Therefore, the indicators used to assess the researcher must be carefully chosen.

Another limitation is that traditional bibliometric tools such as citation indices assume that if a paper is cited, it is because it is useful. However, papers are cited for multiple reasons such as negative citations disputing results or theories. Papers that have been cited previously may hence be added rather than actually read. Bibliometrics does not account for whether a citation is presented in a negative or positive context, which may affect the overall impact of a researcher's academic standing. Citation patterns also differ greatly between disciplines and it is important to compare researchers or groups of researchers against those from the same or similar discipline.

Other problems with bibliometrics include a tendency to focus on journal articles with less emphasis on publications in books where some excellent contributions have been made. New journals tend to fare poorly than old journals. Language bias also affects research evaluation metrics. First-rate research published in a language other than English may not be included in the databases, so key research may well be overlooked, particularly when there are research programs more relevant to specific geographical locations.

Databases and the web-based tools for analysis are owned by large publishing companies. Clearly, it is in their interests to establish that their journals are the most prestigious, which in turn may bias the information distilled from them. One must also be wary about commercial interests taking precedent when a new data tool becomes available. Unscrupulous practices such as citing one's own and one's colleagues work inappropriately or splitting outputs into multiple articles can lead to a falsely high citation ranking. However, some newer metrics permits exclusion of self-citation.

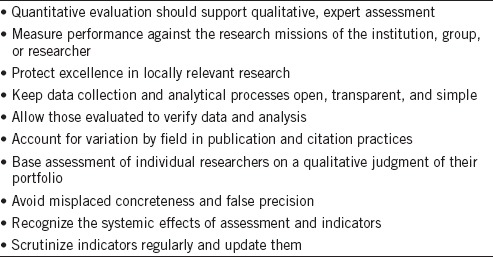

Concerns have been raised about the overuse and abuse of metrics in evaluating the competency of a researcher's work when evaluation is led by data rather than informed judgment, hence the creation of the Leiden Manifesto, which lays out 10 principles of the best practice in metrics-based research assessment (Table 7).68

Table 7.

The Leiden Manifesto: Ten principles of best practice in metrics-based research assessment68

Bibliometrics focuses on quantity rather than on quality measures. While it provides a benchmark for impact of research, it does not necessarily mean that the quality of the work is high. Evaluation of a researcher or groups of researchers by data alone overlooks other qualitative attributes that can only be measured using appropriate peer review. When assessing a researcher's academic standing, it is essential to read their publications and to make a personal judgment of the research. This will help assess their level of expertise and experience that the metrics alone may not necessarily be able to identify. Other markers of achievement outside of laboratory research, such as presentations given at international conferences, grants awarded, and patents, must also be taken into account, as they will contribute toward a researcher's influence in the academic world. Indeed, a research scientist should be judged on scientific merit rather than on journal publication impact alone.

CONCLUSIONS