Abstract

“Autism Spectrum Disorders” (ASDs) are neurodevelopment disorders and are characterized by persistent impairments in reciprocal social interaction and communication. Sleep problems in ASD, are a prominent feature that have an impact on social interaction, day to day life, academic achievement, and have been correlated with increased maternal stress and parental sleep disruption. Polysomnography studies of ASD children showed most of their abnormalities related to rapid eye movement (REM) sleep which included decreased quantity, increased undifferentiated sleep, immature organization of eye movements into discrete bursts, decreased time in bed, total sleep time, REM sleep latency, and increased proportion of stage 1 sleep. Implementation of nonpharmacotherapeutic measures such as bedtime routines and sleep-wise approach is the mainstay of behavioral management. Treatment strategies along with limited regulated pharmacotherapy can help improve the quality of life in ASD children and have a beneficial impact on the family. PubMed search was performed for English language articles from January 1995 to January 2015. Following key words: Autism spectrum disorder, sleep disorders and autism, REM sleep and autism, cognitive behavioral therapy, sleep-wise approach, melatonin and ASD were used. Only articles reporting primary data relevant to the above questions were included.

Keywords: Autism, autism spectrum disorder children, melatonin and autism, rapid eye movement sleep and autism, sleep disorders and autism, sleep disorders in autism, sleep in autistic kids

Introduction

“Autism Spectrum Disorders” (ASDs) are neurodevelopment disorders with a heterogeneous spectrum of clinical symptomatology related to social interaction and communication. ASD is characterized by persistent impairments in reciprocal social interaction and communication across multiple contexts, along with the presence of restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behaviors and interests. Children with ASD often exhibit high levels of co-occurring behavioral issues.[1] Sleep problems in ASD, are a prominent feature and occurs secondary to complex interactions among biological, psychological, social/environmental and family factors, and child rearing practices that may not be conducive to good sleep.

Methodology

PubMed search was performed for English language articles from January 1995 to January 2015.

Following key words: Autism spectrum disorder, sleep disorders and autism, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and autism, cognitive behavioral therapy, sleep-wise approach, melatonin and ASD were used.

Only articles reporting primary data relevant to the above questions were included.

Pevalence sleep disorders in autism spectrum disorder

ASD is a neurodevelopmental disorder and can present with varying severity. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention report (2008) indicates that the prevalence of ASD is one in 88 children with a 4.6:1 male to female ratio. According to the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, in 2000, the prevalence of ASD children was found to be 1 in 150 children, in 2008 it was found to be 1 in 88 children, and in 2010 the prevalence was 1 in 68 children.[2]

Children and adolescents with ASD suffer from sleep problems, particularly insomnia, at a higher rate than typically developing (TD) children, ranging from 40% to 80%.[3]

A study based on parental reports showed that 53% of children (2–5 years of age) with ASD suffered from a sleep problem.[4] 56/89 children with ASD (n = 89) had sleep disorders (difficulty falling asleep = 23, frequent awakening = 19, and early morning awakening = 11) with varying presentations of insomnia.[5] 86% of children (n = 167), suffered from sleep problems daily. The spectrum of sleep disturbances included 54% bedtime resistance problems, 56% insomnia, 53% parasomnias, 25% sleep disordered breathing, 45% morning arising problems, and 31% daytime sleepiness. Hence, there is a lot of evidence to show that sleep disturbance is very common in ASD children.[6]

Etiology of sleep problems in autism

The etiologies of sleep disorders in ASD children is multifactorial, with genetic, environmental, immunological, and neurological factors thought to play a role in the development of ASD. There is evidence that there is an association between the sleep and melatonin rhythms with alterations in this synchronization of the melatonin rhythm causing sleep problems. Neurotransmitters such as serotonin, GABA, and melatonin are required for establishing a regular sleep wake cycle. Any impairment in the production of these neurotransmitters may disrupt sleep.[7] Melatonin is a hormone that helps in maintaining and synchronizing the circadian rhythm. Melatonin regulation may be abnormal in autism. Clock genes may be involved in the modulation of melatonin and also in the integrity of synaptic transmissions in ASD.[8] Exogenous therapy of melatonin has shown to improve the sleep patterns in ASD children.[9] In melatonin synthesis, the final enzyme encoded by the N-acetylserotonin O-methyltransferase gene demonstrated less activity in ASD children; therefore, implying lower levels of melatonin.[10] The major sleep promoting area, that is, the preoptic area in the hypothalamus uses GABA as a neurotransmitter. In autism, GABAergic interneurons migration and maturation may be affected. A region of genetic susceptibility has been identified on chromosome 15q that contains GABA-related genes.[25] Vitamin D is required for embryogenesis, neural development, and also for activating certain genes, deficiency in this vitamin during pregnancy could be an environmental risk factor for the development of ASD.[11]

Sleep architecture and its clinical relevance

Polysomnography (PSG) studies of ASD children showed most of their abnormalities related to REM sleep which included decreased quantity, increased undifferentiated sleep, immature organization of eye movements into discrete bursts, decreased time in bed, total sleep time (TST), REM sleep latency, and increased proportion of stage 1 sleep. Greater number of muscle twitches compared with healthy controls are reported.[12,13] 5 of 11 children with ASD with disrupted sleep had nocturnal awakenings, REM sleep behavior disorder, with lack of muscle atonia during REM sleep.[14] A study between the children with ASD in comparison to TD showed that ASD children had longer sleep onset latency (SOL), reduced sleep efficiency, and increased wake after sleep onset compared to controls, no significant differences in the sleep stage percentages between the two groups was seen. Neither group demonstrated correlations between sleep stage percentages and cognitive test scores. Children with ASDs have more disturbed sleep and affective problems than TD children.[15]

Affective problems improve with increased sleep, particularly REM and slow wave sleep, in TD children, but not in children with ASDs. Reduced TST has been shown to correlate with Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) severity and inversely related to social quotient in a pilot study. SOL and REM latency were higher in children with moderate to severe attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. A trend was observed in the correlation of higher CARS being related to lower REM percentage and reduced TST to higher REM latency.

Impact of sleep disturbances in children with autism spectrum disorders on care-givers

Sleep problems in ASD have also been correlated with increased maternal stress and parental sleep disruption. Children with ASD have common sleep disturbances that could negatively impact not only the quality of life and the daytime functioning of the child, but also the family, increasing the stress level. This has also shown to have an association with more challenging behaviors of ASD children during the day and have an impact on the ability to regulate emotion.[16] Common medical issues such as upper respiratory problems and vision problems have shown an association with sleep quality. Increased night time awakening and decreased willingness to fall asleep were shown to be associated with poor appetite and growth.[17] Increased aggression, hyperactivity, and social difficulties could be indicators for poor mental health outcomes that were observed due to sleep disturbance in children with ASD.

Assessment of sleep problems in autism spectrum disorders

An early and routine assessment of sleep in children with ASD could help children as well as their parents. Sleep may be assessed utilizing subjective and/or objective measures.[18] Subjective measures would include parental questionnaires and sleep diaries whereas objective measures would include actigraphy and PSG for assessing the sleep disorders.[19] Actigraphy is a study in which an actigraph device is worn on the wrist to record movements that can be used to estimate sleep parameters with specialized algorithms in computer software programs. PSG is continuous monitoring of multiple neurophysiological and cardiorespiratory variables, usually over the course of a night, to study different aspects of sleep. Psychological assessments, detailed history from parents, teachers, and care-givers that describes the child's current sleep problem is obtained.

The sleep history should include:

Predisposing factors (e.g., developmental vulnerabilities)

Precipitating factors (e.g., onset of medical conditions or medications; poor sleep hygiene)

Perpetuating factors (e.g., napping during the day, co-sleeping, and parenting behaviors). Maintaining a sleep log or a sleep dairy could help determine factors that might be resulting in poor sleep.

Establishing positive sleep patterns for young children with autism spectrum disorder

Children with ASD may experience various sleep complaints such as difficulty falling asleep, analysis of frequent awakening during the night, and/or reduced TST. Ongoing and persistent sleep disturbances can have an adverse effect on the child, parents, and other household members.

Reinforcing a positive sleep pattern is of paramount importance.

Following are helpful strategies:

Assessment of any underlying medical problems such as tonsillitis, adenoids, gastrointestinal disturbances, and seizures that may affect sleep

Evaluation of bedtime routines

Screening for intrinsic sleep disorders such as sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, or periodic limb movement disorder

Assessment for food and/or environmental allergies that are commonly observed in ASD.

Environmental variables

Assess the environmental variables that could affect the child's sleep such as temperature of the room, bedding, and sleep clothes. Certain textures can relax or arouse your child that could be disturbing the child's sleep. Consider noises levels, visual stimuli in the room, and how they affect the child.

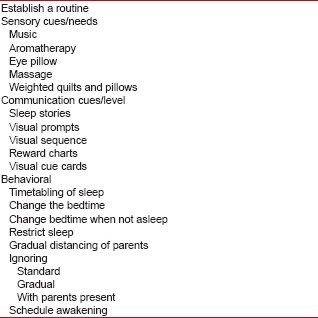

Bedtime routines

Bedtime rituals are very important for most children, they help in establishing positive sleep patterns. Make a visual bedtime schedule and pick a specific time for bed that is reasonable, provide reminders and consistency for the whole family. A good bedtime routine will help teach a child to calm down, relax, and get ready to sleep.

Sleep training

After the bedtime routine is done and the child is in his bed or crib- but is upset and obviously not sleeping, wait a few minutes and then go back into the child's room to check on him/her. Checks involve going back into the child's room and briefly (not more than a minute, preferably less) touching, rubbing, or maybe giving a “high five,” “thumbs up,” or hug for an older child who better responds to these gestures. Gently but firmly say, “it's okay, it's bedtime, you are okay” or a similar phrase and then leave the room until it is time for the next check or until the child falls asleep. It is important to know that it is very likely that the child's behavior will get worse for a few days or more before it improves.

Role of pharmacotherapy

If the child does not respond to behavioral changes advised, then medications may be considered. Medications such as benzodiazepines and diphenhydramine given as over-the-counter drugs were shown to have paradoxical and excitatory responses that have been reported.[20]

The alpha-2 adrenergic agonist, clonidine reduced the time to sleep and also nighttime awakenings, this was observed in a small open label trial.[21]

Role of melatonin

Melatonin is a pineal hormone that regulates the circadian rhythm. Melatonin appears to be effective in reducing time to sleep, but its efficacy in reducing nighttime awakenings and other aspects of sleep disturbances is variable.[22] In a study, n = 24, 1–3 years ASD children, when treated with 1 mg or 3 mg showed improvement in sleep latency that was measured by actigraphy. This treatment not only showed an improvement in the sleep pattern of the children, but also the behavior and parental stress.[23] In another study, n = 107, ASD children (2–18 years), after receiving melatonin 0.75–6 mg, 25% of the parents had no more sleep concerns, 60% reported improved sleep, 13% continued to have sleep as a major problem, 1% had worsened sleep after initiating melatonin, and 1% could not determine the response.[24]

Children with autism and neurological impairments present special challenges for drug administration. They may present with unusual feeding difficulties and restrictive diets. Parents often have to be extremely creative in disguising or mixing medication with the right type of liquid or food. Melatonin can also be administered in toothpaste form.

Conclusion

There is a high prevalence of sleep disturbances among children with ASD, many of which are unrecognized. Sleep disturbances have an adverse effect on their social interaction, academic achievement, and well-being of the care-givers.

Implementation of nonpharmacotherapeutic measures such as bedtime routines and sleep-wise approach are the mainstay of management.

These treatment strategies along with limited regulated pharmacotherapy can help improve the quality of life in ASD children and also decrease the family and parental distress.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Boonen H, Maljaars J, Lambrechts G, ZInk I, Van Leeuwen K, Noens I. Behavior problems among school-aged children with autism spectrum disorder: Associations with children's communication difficulties and parenting behaviors. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2014;8:716–25. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baio J. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years – Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:2:1–21. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/library/sciclips/issues/v6issue16.html . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cortesi F, Giannotti F, Ivanenko A, Johnson K. Sleep in children with autistic spectrum disorder. Sleep Med. 2010;11:659–64. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krakowiak P, Goodlin-Jones B, Hertz-Picciotto I, Croen LA, Hansen RL. Sleep problems in children with autism spectrum disorders, developmental delays, and typical development: A population-based study. J Sleep Res. 2008;17:197–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00650.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taira M, Takase M, Sasaki H. Sleep disorder in children with autism. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;52:182–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1998.tb01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu X, Hubbard JA, Fabes RA, Adam JB. Sleep disturbances and correlates of children with autism spectrum disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2006;37:179–91. doi: 10.1007/s10578-006-0028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cortesi F, Giannotti F, Ivanenko A, Johnson K. Sleep in children with autistic spectrum disorder. Sleep Med. 2010;11:659–64. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourgeron T. The possible interplay of synaptic and clock genes in autism spectrum disorders. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2007;72:645–54. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2007.72.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leu RM, Beyderman L, Botzolakis EJ, Surdyka K, Wang L, Malow BA. Relation of melatonin to sleep architecture in children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41:427–33. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1072-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melke J, Goubran Botros H, Chaste P, Betancur C, Nygren G, Anckarsäter H, et al. Abnormal melatonin synthesis in autism spectrum disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:90–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duan XY, Jia FY, Jiang HY. Relationship between Vitamin D and autism spectrum disorder. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2013;15:698–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elia M, Ferri R, Musumeci SA, Del Gracco S, Bottitta M, Scuderi C, et al. Sleep in subjects with autistic disorder: A neurophysiological and psychological study. Brain Dev. 2000;22:88–92. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(99)00119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malow BA, Marzec ML, McGrew SG, Wang L, Henderson LM, Stone WL. Characterizing sleep in children with autism spectrum disorders: A multidimensional approach. Sleep. 2006;29:1563–71. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.12.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thirumalai SS, Shubin RA, Robinson R. Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder in children with autism. J Child Neurol. 2002;17:173–8. doi: 10.1177/088307380201700304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maski K, Holbrook H, Manoach D, Hanson E, Stickgold R. Sleep architecture and neurobehavioral and cognitive functioning in children with autistic spectrum disorders. Neurology. 2013;80 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gail Williams P, Sears LL, Allard A. Sleep problems in children with autism. J Sleep Res. 2004;13:265–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2004.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.May T, Cornish K, Conduit R, Rajaratnam SM, Rinehart NJ. Sleep in high-functioning children with Autism: Longitudinal developmental change and associations with behaviour problems. Behav Sleep Med. 2015;13:2–18. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2013.829064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeste SS. The neurology of autism spectrum disorders. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011;24:132–9. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283446450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsai L. Children with autism spectrum disorder: Medicine today and in the new millennium. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl. 2000;15:138–45. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ming X, Gordon E, Kang N, Wagner GC. Use of clonidine in children with autism spectrum disorders. Brain Dev. 2008;30:454–60. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myers SM, Johnson CP. American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children With Disabilities. Management of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1162–82. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malow B, Adkins KW, McGrew SG, Wang L, Goldman SE, Fawkes D, et al. Melatonin for sleep in children with autism: A controlled trial examining dose, tolerability, and outcomes. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42:1729–37. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1418-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersen IM, Kaczmarska J, McGrew SG, Malow BA. Melatonin for insomnia in children with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Neurol. 2008;23:482–5. doi: 10.1177/0883073807309783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCauley JL, Olson LM, Delahanty R, Amin T, Nurmi EL, Organ EL, et al. A linkage disequilibrium map of the 1-Mb 15q12 GABA (A) receptor subunit cluster and association to autism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2004;131B:51–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]