Abstract

Background:

Encephalocele is the protrusion of the cranial contents beyond the normal confines of the skull through a defect in the calvarium and is far less common than spinal dysraphism. The exact worldwide frequency is not known.

Aims and Objectives:

To determine the epidemiological features, patterns of encephalocele, and its postsurgical results.

Materials and Methods:

The study was carried from year July 2012 to June 2015. Patients with encephalocele were evaluated for epidemiological characteristics, clinical features, imaging characteristics, and surgical results.

Results:

20 encephaloceles patients were treated during the study period. Out of these 12 (60%) were male and 8 (40%) female. Age range was 1 day to 6 years. The most common type of encephalocele was occipital 12 (60%), occipito-cervical 4 (20%), parietal 2 (10%), fronto-nasal 1 (5%), and fronto-naso-ethmoidal 1 (5%). One patient had a double encephalocele (one atretic and other was occipital) with dermal sinus tract and limited dermal myeloschisis. Other associations: Chiari 3 malformation (2), meningomyeloceles (4), and syrinx (4). Three patients presented with rupture two of whom succumbed to meningitis and shock. Seventeen patients treated surgically did well with no immediate surgical mortality (except a case of Chiari 3 malformation who succumbed 6 months postsurgery to unrelated causes). Shunt was performed in 4 cases.

Conclusion:

The most common type of encephalocele is occipital in our set up. Early surgical management of encephalocele is not only for cosmetic reasons but also to prevent tethering, rupture, and future neurological deficits.

Keywords: Encephalocele, occipital, sincipital, split pons, surgical management

Introduction

Encephalomeningocele is a congenital malformation characterized by protrusion of meninges and/or brain tissue due to a skull defect. It is one form of neural tube defects as the other two, anencephaly and spina bifida.[1]

Despite the higher incidence of this congenital defect in this area, little is known about its etiology and pathogenesis. Some evidence from previous studies suggest environmental factors as potential causes.[1,2,3,4] So far, only aflatoxin has been proposed to be a teratogenic agent for this anomaly.[2] Indirect evidences from its closely related anomaly, spina bifida,[5] may suggest the role of folate deficiency in encephalomeningocele. However, again, there were no studies on the relationship between maternal folate level and incidence of encephalomeningocele, and some evidences have suggested different underlying mechanisms between these two forms of neural tube defects.[6,7,8]

Here, we report 20 cases of encephaloceles in 19 patients and review their epidemiological, clinical, imaging characteristics, as well as analyze the surgical results.

Aims and objectives

The aims and objectives of the study are to observe and analyze the epidemiological, clinical, imaging characteristics, as well as analyze surgical results of all cases of encephaloceles that were treated at our institute from July 2012 to June 2015.

Materials and Methods

The study is a prospective observational study conducted from 2012 July to 2015 June. A total of 20 cases of encephalocele in 19 patients were analyzed during the study period. Patients with encephalocele were evaluated for epidemiological characteristics, clinical features, imaging characteristics, and surgical results. Data were recorded from case records, operation notes, and death records.

Results

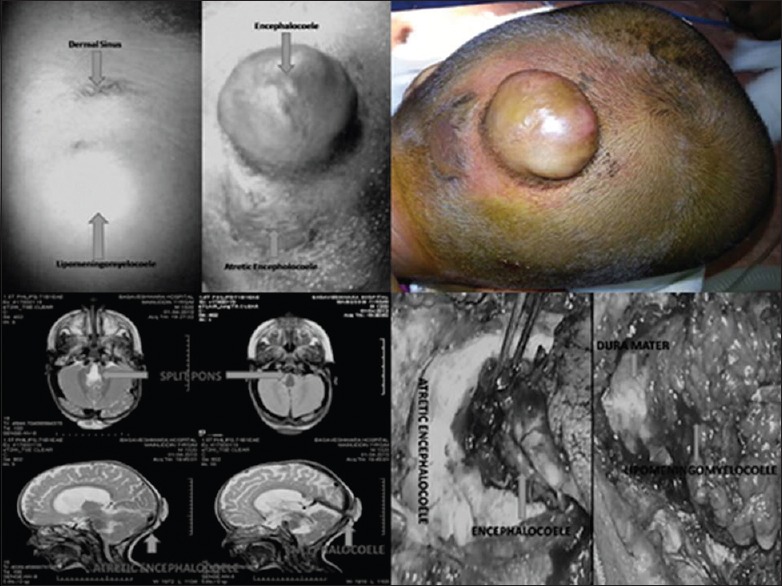

A total of 20 encephaloceles cases in 19 patients were treated during the study period. One patient had a double encephalocele one of which was atretic [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Clinical photographs and magnetic resonance imaging images of double encephalocele

Epidemiological features

Out of the 20 encephaloceles, 12 (60%) were male and 8 (40%) female patients. The youngest was a 1-day old infant while the oldest child presented at 6 years of age (median = 1 month, mode = 1 month) [Table 1]. Adequate antenatal checkup and folic acid supplementation were received by mothers. However, none of them received preconceptional folic acid. One patient was given a normal report on preoperative scan. The mode of delivery in most of the cases was by cesarean section. Only one patient was delivered per vagina.

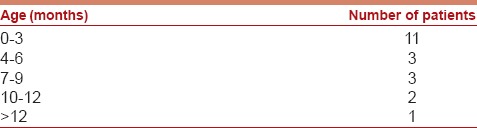

Table 1.

Age Distribution

Pattern and clinical features

Most common type of encephalocele was occipital. Occipital encephaloceles accounted for 12 (60%), occipito-cervical 4 (20%), parietal 2 (10%), fronto-nasal 1 (5%), and fronto-naso-ethmoidal 1 (5%). One patient had a double encephalocele (one atretic and other was occipital) with dermal sinus tract and limited dermal myeloschisis and a split pons. Other associations: Chiari 3 malformation (2), meningomyeloceles (4), and syrinx (4). Three patients presented with ruptured encephalocele [Table 2].

Table 2.

Associated anomalies

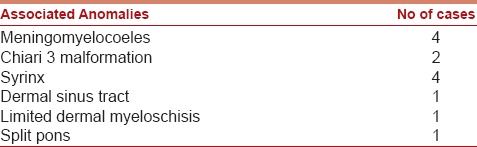

Imaging

All patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging scan of the head with screening of whole spine (except patients with ruptured encephaloceles). On imaging, 2 patients had only meningoceles, 2 were atretic, while the rest had varying content of brain tissue [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging images

Clinical course and surgical treatment

Three patients presented with rupture, one of whom succumbed to shock even before surgery. Of the other 2 patients, in whom repair of sac was performed, the patient with meningocele improved while the patient with encephalocele succumbed to meningitis and shock.

One patient with fronto-naso-ethmoidal encephalocele was managed with combined open and endoscopic approach. Rest patients underwent open exploration and repair.

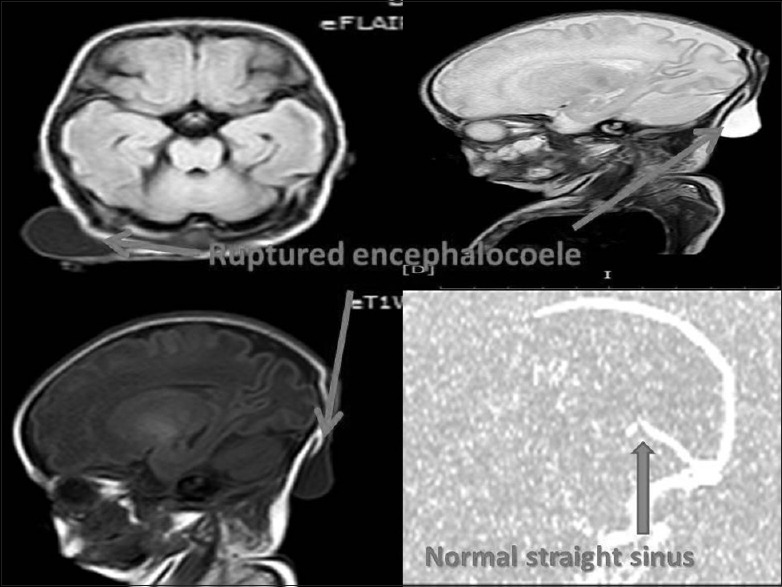

The other 17 encephaloceles treated surgically did well with no immediate surgical mortality [Figure 3]. One child with Chiari 3 malformation succumbed 6 months postsurgery to unrelated causes. Shunt was performed in 4 cases due to the development of hydrocephalus. Wound site infection and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak was seen in 4 cases which were conservatively managed with 1 patient requiring re-exploration and repair. The case with fronto-nasal encephalocele developed ocular CSF leak which was conservatively managed.

Figure 3.

Pre- and post-operative images of representative cases

The follow-up period ranged from 6 months to 3 years.

Discussion

Encephaloceles represents a congenital defect of the cranium in which a portion of central nervous system herniates through the defect. It is a common congenital problem in the practice of neurosurgery worldwide.[9]

Occipital encephaloceles can vary from a small swelling to extremely large one. In our series, the most common site was occipital. The contents of the sac vary from small dysplastic diverticulum to a large amount of degenerative brain tissue. Large sacs were always filled with CSF with or without septations. The bony defect can vary in size. In one of the interesting case of ruptured meningocele, the defect had almost closed and hence the patient had a good outcome despite presenting with rupture.

Male predominance was found in our series compared to other series[10,11] with most children presenting within 1 month. Only one child presented at the age of 6 years.

Elective surgery provides time for the patients to gain weight and strength and allows the surgeon to select the best technique. Most large encephaloceles required urgent surgical treatment to avoid damage to sac. In all the occipital, parietal and nasal encephaloceles there was dysplastic brain tissue which was removed safely.

Postoperative hydrocephalus should be managed through ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunts as one or two-stage procedures.[12] Four of our cases required postoperative VP shunt in addition to the repair of the sac. In one case of fronto-naso-ethmoidal encephalocele, combined open and endoscopic procedures were utilized.

The immediate outcome was good in all except in 2 patients. Both patients had ruptured encephaloceles. One of the patients succumbed before surgery. The other patient died due to intractable meningitis and sepsis.

CSF leak and wound infection observed in four cases improved on conservative treatment. An interesting result of CSF leak through eyes was noted in one of the cases with fronto-nasal encephalocele.

Conclusion

The most common type of encephalocele is occipital in our set up. Early surgical management of encephalocele is not only for cosmetic reasons but also to prevent tethering, rupture, and future neurological deficits. Complications like hydrocephalus may need to be managed with shunt surgery. Endoscopic procedures play an important role in fronto-naso-ethmoidal encephaloceles.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Suwanwela C, Sukabote C, Suwanwela N. Frontoethmoidal encephalomeningocele. Surgery. 1971;69:617–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thu A, Kyu H. Epidemiology of frontoethmoidal encephalomeningocoele in Burma. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1984;38:89–98. doi: 10.1136/jech.38.2.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richards CG. Frontoethmoidal meningoencephalocele: A common and severe congenital abnormality in South East Asia. Arch Dis Child. 1992;67:717–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.67.6.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smit CS, Zeeman BJ, Smith RM, de V Cluver PF. Frontoethmoidal meningoencephaloceles: A review of 14 consecutive patients. J Craniofac Surg. 1993;4:210–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christensen B, Rosenblatt DS. Effects of folate deficiency on embryonic development. Baillieres Clin Haematol. 1995;8:617–37. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3536(05)80223-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McComb JG, editor. Neurological Surgery. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1996. Encephaloceles; pp. 829–30. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris MJ, Juriloff DM. Mini-review: Toward understanding mechanisms of genetic neural tube defects in mice. Teratology. 1999;60:292–305. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199911)60:5<292::AID-TERA10>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martínez-Lage JF, Poza M, Lluch T. Craniosynostosis in neural tube defects: A theory on its pathogenesis. Surg Neurol. 1996;46:465–9. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(96)00213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahapatra AK, Agrawal D. Anterior encephaloceles: A series of 103 cases over 32 years. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13:536–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lorber J, Schofield JK. The prognosis of occipital encephalocele. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1967;13:75–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1967.tb02385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shilpakar SK, Sharma MR. Surgical management of encephaloceles. J Neurosci. 2004;1:45–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gamache FW., Jr Treatment of hydrocephalus in patients with meningomyelocele or encephalocele: A recent series. Childs Nerv Syst. 1995;11:487–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00334972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]