Abstract

Objective:

To study the clinical profile and outcome in children with diphtheritic polyneuropathy (DP).

Methodology:

13 children with polyneuropathy were included in this study. Their demographic profile, age, sex and immunization status were recorded. Detailed clinical and neurological examination was done. Investigations like CSF analysis, NCV studies, MRI brain were done. The results were tabulated and analyzed.

Results:

All the children presented with bulbar palsy and had h/o membranous tonsillitis. Isolated palatal palsy was seen in 7 children (53%). 6 (46.1%) children developed quadriparesis. 1 child expired and recovery is complete in rest of the 12 children. Children with isolated bulbar palsy recovered within 2 to 4 weeks while children with quadriparesis recovered within 5-6 wks.

Conclusions:

Any child diagnosed with diphtheria should be followed for 3-6 months in anticipation of neurological complications. DP carries good prognosis hence timely diagnosis and differentiation from other neuropathies is a prerequisite for rational management.

Keywords: Anti-diphtheritic serum, complications, diphtheria, polyneuropathy

Introduction

Diphtheritic polyneuropathy (DP) is recognized as one of the most severe complications of diphtheria, caused by exotoxin of Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Among 20,000 cases of diphtheria reported by WHO during 2007–2011, 17,926 (89.6%) cases were from India alone.[1] Most persons with diphtheria in India are either partially immunized or unimmunized.

Scarce reports of DP in the Indian literature may result from under-recognition and perhaps, under-reporting of this entity. In this paper, we present a case series of 13 children with DP from South India admitted in our hospital from July 2013 to December 2013.

During the same period, 19 children admitted with membranous tonsillitis in our hospital were identified as probable or confirmed cases of diphtheria with culture positivity in 13 children. They were treated with anti-diphtheritic serum (ADS) and antibiotics. Among 19 children, 7 children expired and the rest were followed for 6 months.

The simultaneous resurgence of clinical diphtheria in our area helped us probe into the history of those children who presented with neuropathy and throw light on this latent entity which is almost forgotten by the present day physicians and neurologists. In India, apart from the case series from Delhi, there is no other case series reported so far in the recent past.

Methods

Thirteen children with DP were included in this study. Their demographic profile, age, sex, and immunization status were recorded. Detailed clinical and neurological examination was done. Investigations such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, nerve conduction velocity (NCV) studies, Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain were carried out. The results were tabulated and analyzed. Among 13 children, 10 presented with neuropathy whose past histories revealed membranous tonsillitis. Three children presented to us with respiratory diphtheria and developed neuropathy during follow-up.

Results

Children in the present series were in the age group of 5–13 years. All the children had history of membranous tonsillitis with a latency period of 15–40 days between the onset of tonsillitis and neurological symptoms.

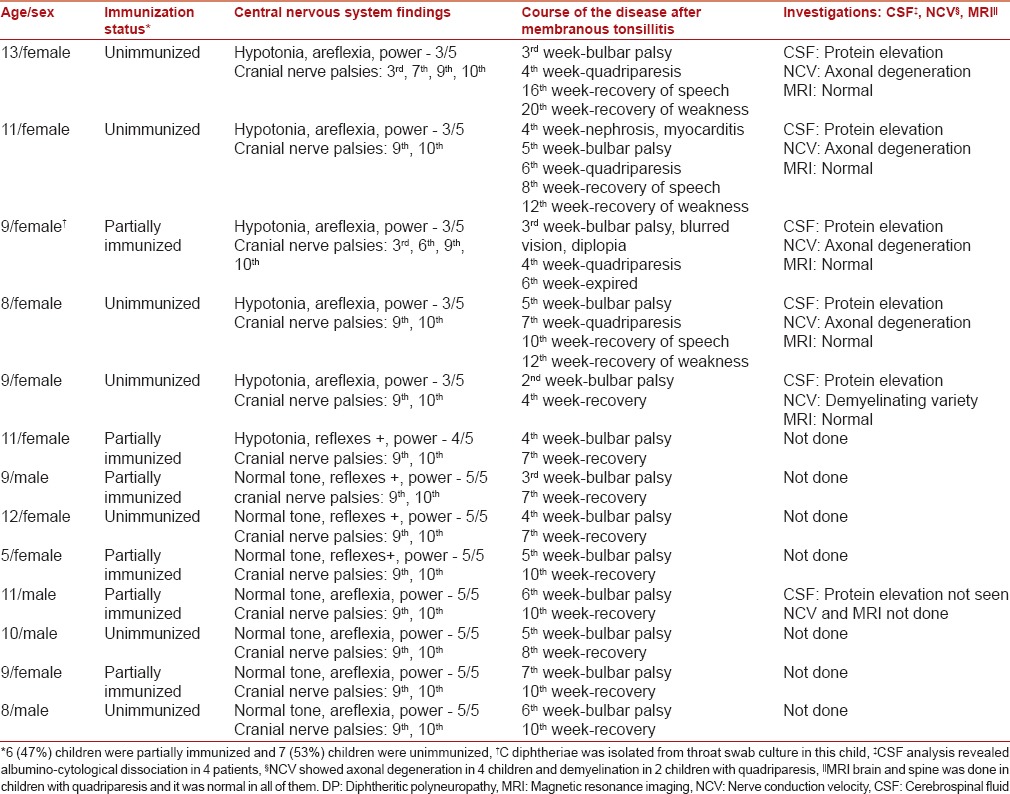

All 13 children had bulbar palsy. Isolated palatal palsy was seen in 7 children (53%). Oculomotor nerve involvement in the form of accommodation paralysis was seen in 3 children. One child had unilateral lower motor neuron facial palsy and 6 children developed quadriparesis after palatal palsy, which was descending and symmetric in nature [Table 1].

Table 1.

Details of children with DP

Supportive treatment with Ryle's tube feeding was given to all children for 1–4 weeks.

One child expired during hospital stay due to aspiration. Recovery was complete in rest of the 12 children.

Children with isolated bulbar palsy recovered within 2–4 weeks while children with quadriparesis recovered within 5–6 weeks.

Discussion

The incidence of neurologic complications is related directly to the severity of respiratory symptoms. DP is seen in 20% and 75% of patients with mild and severe infection, respectively.[2]

The period between the appearance of first symptom of diphtheria and the development of DP is termed latency, which varies from 10 days to 3 months.[3] The first indication of neuropathy is paralysis of the soft palate and posterior pharyngeal wall.[4] Bulbar dysfunction typically develops during the first 2 weeks. Oculomotor and ciliary paralyses seen after 3 weeks are common and distinctive features of DP.

Peripheral neuritis develops later, from 10 days to 3 months after the onset of oropharyngeal disease. In some patients, there may be a secondary worsening of the bulbar symptoms along with the occurrence of peripheral neuropathy.[2] Biphasic course of disease was noted only in 2 children in our study which is contradictory to other studies.

Various studies on major epidemic outbreaks from Russia and Europe in the past gave us valuable insights on pathophysiology and progression of DP. Diptheritic toxin penetrates into Schwann cells and it inhibits the synthesis of myelin proteolipid and basic protein.[4] It was observed in vitro that it binds to Schwann cells as early as 1-hr postinjection, inducing the latent development of polyneuropathy.[5] This stresses the importance of immediate administration of ADS. Local toxic effects occur by direct spread of toxin and result in the early bulbar problems while the ensuing generalized demyelinating neuropathy arises from hematogenous dissemination.[6] The reason behind isolated palatal palsy in few children with no systemic involvement is probably nondissemination of the toxin.

DP has to be distinguished from other neuropathies especially Guillain–Barre syndrome (GBS) which is more common in children. The clinical features differentiating DP from GBS are high prevalence of bulbar palsy, slower evolution of the neuropathy for more than 4 weeks, descending nature, and simultaneous involvement of other organ systems. NCV studies and CSF findings are similar to those in GBS. The management and prognosis of DP differs from GBS.[7]

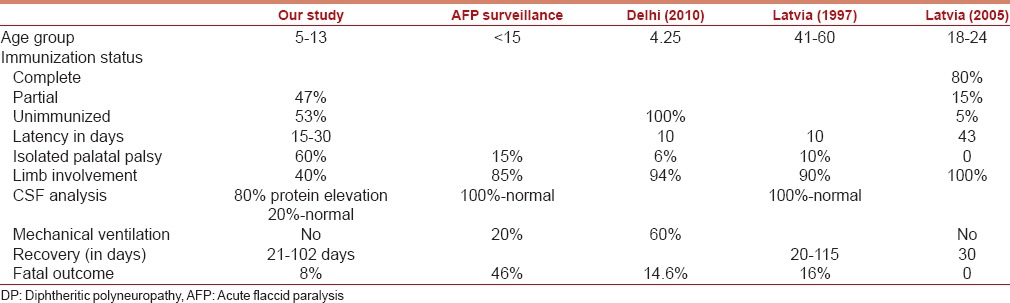

Profile of DP in various studies is described in Table 2. In 2005, Logina and Donaghy reported an attenuated form of neuropathy in the immunized population of Latvia. This was attributed to the protective effects of the vaccine, which attenuated the adverse effects of exotoxin. Compared to the previous epidemic in 1999, the incidence and severity were lower in same area due to early diagnosis and administration of ADS within first 3 days of disease.[8] With this review of literature and supportive evidence from our study, we stress upon the recognition of epidemic in its incipient stage and prompt administration of ADS.

Table 2.

Features of DP in various studies

Studies from Russia showed a significant trend of decreasing immunity with increasing age, resulting in lack of protection, particularly for adults aged 30 to 50 years. As vaccine induced immunity wanes over time, periodic boosters are recommended every 10 years. Thus the susceptibility of adults to diphtheria is a new phenomenon of the vaccine era.[9]

In India, Mohanta and Parija reported 86 cases of DP in children from Odisha in 1974.[10] Mild respiratory muscle involvement was seen in one child in our study in contrast to the study by Sandeep Kumar et al.(2010) from Delhi where respiratory muscles were involved in 85.4% cases and 60.4% required mechanical ventilation.[11] In 2013, Mateen et al. reported a case series of 15 children with DP from nine states and Union territories, detected through Acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance [2002–2008]. Their study demonstrates that DP can be detected through existing AFP surveillance system.

Conclusions

Pediatricians/neurophysicians should have a high index of suspicion to recognize DP in the wake of recent resurgence of diphtheria in some parts of India. Any child diagnosed with probable diphtheria should be followed for 3–6 months for neurological complications.

As seen in our case series, DP carries good prognosis hence timely diagnosis and differentiation from other neuropathies is a prerequisite for rational management and contact tracing.

Continued occurrence of diphtheria emphasizes the need for public health measures such as:

Strengthening of routine immunization and mandatory booster vaccination at school entry and Td booster[12] at 10 years intervals thereafter

Vaccination of susceptible contacts and prophylactic antibiotics to contacts

Ensuring availability of ADS for timely administration and thereby preventing complications

AFP surveillance system can be utilized to identify DP and thus areas of resurgence of diphtheria and strengthen immunization services in those pockets.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Mateen FJ, Bahl S, Khera A, Sutter RW. Detection of diphtheritic polyneuropathy by acute flaccid paralysis surveillance, India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1368–73. doi: 10.3201/eid1909.130117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hadfield TL, McEvoy P, Polotsky Y, Tzinserling VA, Yakovlev AA. The pathology of diphtheria. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(Suppl 1):S116–20. doi: 10.1086/315551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piradov MA, Pirogov VN, Popova LM, Avdunina IA. Diphtheritic polyneuropathy: Clinical analysis of severe forms. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1438–42. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.9.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McAuley JH, Fearnley J, Laurence A, Ball JA. Diphtheritic polyneuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67:825–6. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.6.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pleasure DE, Feldmann B, Prockop DJ. Diphtheria toxin inhibits the synthesis of myelin proteolipid and basic proteins by peripheral nerve in vitro. J Neurochem. 1973;20:81–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1973.tb12106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solders G, Nennesmo I, Persson A. Diphtheritic neuropathy, an analysis based on muscle and nerve biopsy and repeated neurophysiological and autonomic function tests. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989;52:876–80. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.52.7.876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Logina I, Donaghy M. Diphtheritic polyneuropathy: A clinical study and comparison with Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67:433–8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.4.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krumina A, Logina I, Donaghy M, Rozentale B, Kravale I, Griskevica A, et al. Diphtheria with polyneuropathy in a closed community despite receiving recent booster vaccination. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1555–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.056523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hann AF. Resurgence of diphtheria in the newly independent states of the former Soviet Union: A reminder of risk. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67:426. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.4.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohanta KD, Parija AC. Neurological complications of diphtheria. Indian J Pediatr. 1974;41:237–43. doi: 10.1007/BF02829276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanwal SK, Yadav D, Chhapola V, Kumar V. Post-diphtheritic neuropathy: A clinical study in paediatric intensive care unit of a developing country. Trop Doct. 2012;42:195–7. doi: 10.1258/td.2012.120293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Diphtheria: Immunization Surveillance, Assessment, and Monitoring. [Last cited on 2013 Mar 05]. Available from: http://www.who.int/immunization_monitoring/diseases/diphteria/en/index.html .