Abstract

Infectious mononucleosis due to Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is a usually benign systemic viral illness common in children. Many studies described nervous system manifestations of infectious mononucleosis with a wide spectrum of neurologic deficits. Neurologic complications of EBV are seen in both acute and reactivate infection. Herein, we describe a patient diagnosed by acute EBV encephalitis with substantia nigra involvement and excellent clinical recovery.

Keywords: Encephalitis, Epstein–Barr virus, substantia nigra

Introduction

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is the cause of mononucleosis that is generally benign disease in children with classical features of fatigue, pharyngitis, and lymphadenopathy.[1] EBV infections have led to subclinical infection, infectious mononucleosis, and associations with malignancies and central nervous system (CNS) disorders. Many neurological manifestations have been described such as seizures, ataxia, meningitis, encephalitis, transverse myelitis, Guillain–Barre syndrome, autonomic dysfunction, anxiety, and depression in this disease. CNS symptoms can develop in about 1% of cases.[1,2,3] These neurologic symptoms occurring alone or in the course of mononucleosis disease. Although neurologic complications mostly emerge during acute EBV infection, the reactivated virus may also cause neurologic complications in children.[4]

Herein, we describe a patient diagnosed by acute EBV encephalitis with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) lesion in substantia nigra and good recovery with antiviral and steroid treatment.

Case Report

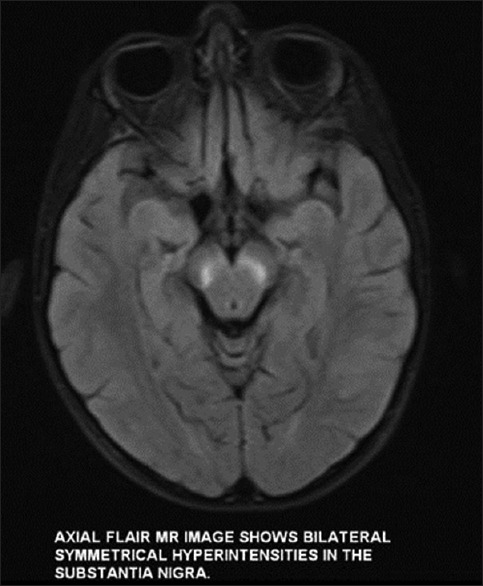

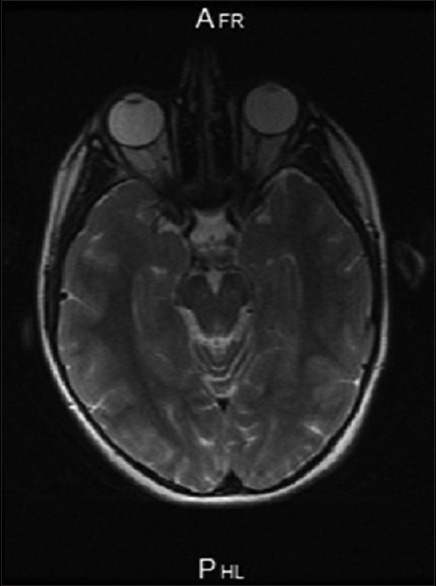

A 8-year-old boy was referred to our hospital for with 8 days history of fever, decreased alertness, drowsiness, vomiting, tremor, and unresponsive to verbal command. He had a history of fever, sore throat, and for this reason penicillin treatment was prescribed at another hospital before 8 days. On admission, patient was febrile and he was unresponsive to verbal command. The pupillary light reflex was evident, no neck stiffness, deep tendon reflexes of the lower and upper extremities were normal. Fundus examination was normal. Other system examinations were normal except pharyngeal injection and tonsiller enlargement with membraneous. Routine biochemical tests and complete blood cell count were normal. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed: 2 lymphocytes/mm3, 18 mg/dl protein, 61 mg/dl glucose (simultaneous blood glucose: 85 mg/dl). MRI revealed bilateral symmetrical hyperintensities in the substantia nigra [Figure 1]. Encephalitis was diagnosed by clinical and radiological findings and empirical antibiotics and acyclovir were administered. Blood and CSF cultures remained negative. Herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, anthyroid antibodies, antinuclear antibody, anti-dsDNA antibody, venereal disease research laboratory, Brucella serology were negative. Serologic studies revealed that weakly positive for: Viral capsid antigen (VCA) IgM, VCA IgG, Epstein–Barr nuclear antigen IgM and early antigen. These results were compatible with acute EBV infection. EBV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was negative in the CSF. High dose steroid was administered for 5 days, after then tapered off. Acyclovir continued for 14 days. After 2 weeks, he recovered without neurological deficits. MRI lesion returned to normal after 2 weeks [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging revealed bilateral symmetrical hyperintensities in the substantia nigra

Figure 2.

Normal magnetic resonance imaging finding after treatment

Discussion

The boy was diagnosed with acute EBV-related encephalitis based on the clinical, radiological findings, and the serological results for EBV. Clinically, EBV can present with meningitis, encephalitis, acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis, cranial nerve palsies, cerebellitis, myelitis, seizures, and polyradiculitis.[4,5,6] It is not known how EBV affect the CNS. Primary inflammation due to direct viral invasion, secondary autoimmune reaction has been postulated mechanisms of EBV encephalitis.[5] Shoji et al. speculated that the neurologic abnormalities were most likely secondary to immune-mediated mechanism.[7] Our patient's sera sample was weakly positive for EBV antibodies but CSF PCR was negative for EBV. This imaging finding together with the negative CSF PCR result for EBV in our patient suggests that an autoimmune mechanism also may be involved in the pathogenesis but we couldn't study autoimmune antibody for technical inadequacy.

EBV can also present with a wide spectrum of imaging abnormalities.[6,8,9] In 40% of cases with EBV encephalitis, radiological anomaly is not seen.[10] EBV has a tropism for the deep nuclei. T2-weighted or fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging reveals multiple focus hyperintensity in the hemispheric cortex, brainstem, bilateral thalami, basal ganglia, and/or splenium.[10,11] Rarely, extensive white matter lesions have been reported in patients with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis associated with chronic EBV infection.[6,12] Also, transient white matter lesions have been described following EBV infection without symptoms.[13]

Most children have a benign clinical course without neurologic sequelae like our patient, but 10% have residual persistent deficits and a mortality rate of up to 10% has been reported.[5,11]

Prognosis was reported to be better for patients with isolated hemispheric grey or white matter involvement. Sequel remains in half of patients with thalamus involvement and mortality rate is highest among patients with brainstem involvement.[14] Generally MRI lesion shows during primary illness but sometimes after recovery of primary infection. Angelini et al. reported that permanent anomalies in the imaging may be related to glial reactions emerging after the recovery of neurological findings.[15]

Substantia nigra, is an important area for the movement. In recent years, literature reported cases of EBV related substantia nigra involvement in children and adult patients. These patients have had parkinsonism symptoms.[16,17] Guan et al. reported a 28-year-old patient presenting to hospital with akinetic rigid syndrome.[16] Lesion in substantia nigra was detected in the MRI. EBV VCA IgM was positive in the CSF and serum. Within 2 months, the patient completely recovered.

Alarcón et al. reported a 20-year-old pregnant women who who presented to hospital with acute parkinsonism with postural and kinetic limb tremor, bradykinesia, nystagmus, saccadic eye movement, and axial dystonia.[17] MRI revealed bilateral symmetric hyperintensity in the subtantia nigra. Serum VCA IgM and CSF EBV PCR were positive in this case. The patient was diagnosed with encephalitis lethargica.

In our patients, lesions were seen in substantia nigra. Bilateral substantia nigra lesions are characteristic of some encephalopathies including the Japanese and West Nile encephalitis.

Antiviral agents and steroids can be used in EBV encephalitis on personal basis. These agents' effectiveness is uncertain.[4,18] Use of corticosteroid can improve clinical prognosis by reducing inflammation and cranial pressure in encephalitis.[19,20] Acyclovir has been recommended for CNS involvement with EBV[19] but white matter lesions have been noted with acyclovir treatment in some cases.[21] Illness is most often benign, but fatal cases have been reported.[9,22] A pediatric study comprising 11 patients, reported that 40% had residual neurologic sequelae such as global impairment, autistic like behavior, and focal paresis was seen in primary infection.[23]

This case demonstrates that EBV-related brainstem encephalitis can be considered as an infectious neurological disease in children. High dose steroid with acyclovir treatment was effective in present case.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Jenson HB. Epstein-Barr virus. Pediatr Rev. 2011;32:375–83. doi: 10.1542/pir.32-9-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson TJ, Glenn MS, Temple RW, Wyatt D, Connolly JH. Encephalitis and cerebellar ataxia associated with Epstein-Barr virus infections. Ulster Med J. 1980;49:158–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hussain RS, Hussain NA. Ataxia and Encephalitis in a Young Adult with EBV Mononucleosis: A Case Report. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2013;2013:516325. doi: 10.1155/2013/516325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Häusler M, Ramaekers VT, Doenges M, Schweizer K, Ritter K, Schaade L. Neurological complications of acute and persistent Epstein-Barr virus infection in paediatric patients. J Med Virol. 2002;68:253–63. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doja A, Bitnun A, Jones EL, Richardson S, Tellier R, Petric M, et al. Pediatric Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Encephalitis: 10-Year Review. J Child Neurol. 2006;21:385–391. doi: 10.1177/08830738060210051101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujimoto H, Asaoka K, Imaizumi T, Ayabe M, Shoji H, Kaji M. Epstein-Barr virus infections of the central nervous system. Intern Med. 2003;42:33–40. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.42.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shoji H, Kusuhara T, Honda Y, Hino H, Kojima K, Abe T, et al. Relapsing acute disseminated encephalomyelitis associated with chronic Epstein-Barr virus infection: MRI findings. Neuroradiology. 1992;34:340–2. doi: 10.1007/BF00588198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shian WJ, Chi CS. Epstein-Barr virus encephalitis and encephalomyelitis: MR findings. Pediatr Radiol. 1996;26:690–3. doi: 10.1007/BF01356839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ono J, Shimizu K, Harada K, Mano T, Okada S. Characteristic MR features of encephalitis caused by Epstein-Barr virus: A case report. Pediatr Radiol. 1998;28:569–70. doi: 10.1007/s002470050416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baskin HJ, Hedlund G. Neuroimaging of herpesvirus infections in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:949–63. doi: 10.1007/s00247-007-0506-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phowthongkum P, Phantumchinda K, Jutivorakool K, Suankratay C. Basal ganglia and brainstem encephalitis, optic neuritis, and radiculomyelitis in Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Infect. 2007;54:e141–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Häusler M, Ramaekers VT, Doenges M, Schweizer K, Ritter K, Schaade L. Neurological complications of acute and persistent Epstein-Barr virus infection in paediatric patients. J Med Virol. 2002;68:253–63. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jang YY, Lee KH. Transient asymptomatic white matter lesions following Epstein-Barr virus encephalitis. Korean J Pediatr. 2011;54:389–93. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2011.54.9.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abul-Kasim K, Palm L, Maly P, Sundgren PC. The neuroanatomic localization of Epstein-Barr virus encephalitis may be a predictive factor for its clinical outcome: A case report and review of 100 cases in 28 reports. J Child Neurol. 2009;24:720–6. doi: 10.1177/0883073808327842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angelini L, Bugiani M, Zibordi F, Cinque P, Bizzi A. Brainstem encephalitis resulting from Epstein-Barr virus mimicking an infiltrating tumor in a child. Pediatr Neurol. 2000;22:130–2. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(99)00124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guan J, Lu Z, Zhou Q. Reversible parkinsonism due to involvement of substantia nigra in Epstein-Barr virus encephalitis. Mov Disord. 2012;27:156–7. doi: 10.1002/mds.23935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alarcón F, Dueñas G, Lees A. Encephalitis lethargica due to Epstein-Barr virus infection. Mov Disord. 2011;26:2132–4. doi: 10.1002/mds.23772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Volpi A. Epstein-Barr virus and human herpesvirus type 8 infections of the central nervous system. Herpes. 2004;11(Suppl 2):120A–7A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamei S, Sekizawa T, Shiota H, Mizutani T, Itoyama Y, Takasu T, et al. Evaluation of combination therapy using aciclovir and corticosteroid in adult patients with herpes simplex virus encephalitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1544–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.049676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakano A, Yamasaki R, Miyazaki S, Horiuchi N, Kunishige M, Mitsui T. Beneficial effect of steroid pulse therapy on acute viral encephalitis. Eur Neurol. 2003;50:225–9. doi: 10.1159/000073864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamura T, Konno K, Matsumoto S, Gotoh T, Watanabe K. A case of herpes simplex encephalitis with cerebral white matter lesion after acyclovir administration. No To Hattatsu. 1990;22:488–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Francisci D, Sensini A, Fratini D, Moretti MV, Luchetta ML, Di Caro A, et al. Acute fatal necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalitis caused by Epstein-Barr virus in a young adult immunocompetent man. J Neurovirol. 2004;10:414–7. doi: 10.1080/13550280490521050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Domachowske JB, Cunningham CK, Cummings DL, Crosley CJ, Hannan WP, Weiner LB. Acute manifestations and neurologic sequelae of Epstein-Barr virus encephalitis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:871–5. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199610000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]