Abstract

One set of missense mutations in the neuron specific beta tubulin isotype 3 (TUBB3) has been reported to cause malformations of cortical development (MCD), while a second set has been reported to cause isolated or syndromic Congenital Fibrosis of the Extraocular Muscles type 3 (CFEOM3). Because TUBB3 mutations reported to cause CFEOM had not been associated with cortical malformations, while mutations reported to cause MCD had not been associated with CFEOM or other forms of paralytic strabismus, it was hypothesized that each set of mutations might alter microtubule function differently. Here, however, we report two novel de novo heterozygous TUBB3 amino acid substitutions, G71R and G98S, in four patients with both MCD and syndromic CFEOM3. These patients present with moderately severe CFEOM3, nystagmus, torticollis, and developmental delay, and have intellectual and social disabilities. Neuroimaging reveals defective cortical gyration, as well as hypoplasia or agenesis of the corpus callosum and anterior commissure, malformations of hippocampi, thalami, basal ganglia and cerebella, and brainstem and cranial nerve hypoplasia. These new TUBB3 substitutions meld the two previously distinct TUBB3-associated phenotypes, and implicate similar microtubule dysfunction underlying both.

Keywords: tubulin, congenital fibrosis of extraocular muscles, tubulinopathy, cortical development, TUBB3

Introduction

TUBB3 encodes beta tubulin isotype 3, a neuron-specific component of microtubules. Heterozygous missense mutations in TUBB3 have been reported to cause two distinct congenital neurodevelopmental pathologies: isolated or syndromic congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles type 3 (CFEOM3) [Tischfield et al., 2010], or malformations of cortical development including dysgyria (MCD) [Poirier et al., 2010; Bahi-Buisson et al., 2014; Oegema et al., 2015].

Nine unique heterozygous TUBB3 missense mutations, resulting in TUBB3 amino acid substitutions G82R, T178M, E205K, A302V, M323V, M388V, R46G, P357L, and E288K, have been reported to cause MCD, of which only E205K has been reported in more than one proband [Poirier et al., 2010; Bahi-Buisson et al., 2014; Oegema et al., 2015]. Affected children are often referred to specialists at school age for developmental delay and intellectual disabilities, epilepsy, hypotonia, and spasticity. They can have nystagmus, nonparalytic strabismus, or oculomotor apraxia but have not been reported to have CFEOM or other cranial or peripheral nerve findings. Neuroimaging reveals mild focal or multifocal polymicrogyria-like cortical dysplasia or simplified gyral patterns, often accompanied by agenesis of the corpus callosum, dysmorphic basal ganglia, and cerebellar, corticospinal, and brainstem hypoplasia. These mutations appear to disrupt heterodimer formation, and have been reported to be associated with decreased microtubule stability [Poirier et al., 2010; Tischfield et al., 2011]. No genotype–phenotype correlations have been reported that permit distinctions among MCD TUBB3 patients harboring different mutations.

CFEOM is a severe congenital form of incomitant, paralytic strabismus with restricted vertical, and typically also horizontal, eye movements together with ptosis [Heidary et al., 2008; Graeber et al., 2013], and results from errors in oculomotor nerve development. CFEOM1 is primarily caused by recurrent heterozygous missense mutations in KIF21A that attenuate autoinhibition of the KIF21A kinesin anterograde motor protein and result in an isolated eye movement disorder [Yamada et al., 2003, 2005; Tischfield et al., 2010; Cheng et al., 2014]. By contrast, CFEOM3 has been reported to result from eight heterozygous TUBB3 missense mutations. Four of these have been reported in multiple unrelated probands, and give rise to notable genotype-phenotype correlations.

The four TUBB3-CFEOM mutations resulting in amino acid substitutions R62Q, R262C, A302T, and D417N, are typically inherited and are associated with milder phenotypes. The recurrent R262C substitution and the R62Q substitution cause isolated CFEOM3, which can be unilateral or asymmetric. Such patients do not have other neurological symptoms, are developmentally normal, and have normal brain imaging (R62Q) or asymmetric basal ganglia and thin to absent anterior commissure (R262C). Patients with the A302T substitution have variable eye phenotypes, corpus callosum hypoplasia and mild intellectual impairments. Patients with the recurrent D417N sustitution have moderate CFEOM3, hypoplasia of the posterior body of the corpus callosum, and in adulthood develop a progressive axonal sensory polyneuropathy, but are otherwise developmentally normal [Tischfield et al., 2010].

The four TUBB3-CFEOM mutations resulting in amino acid substitutions R262H, R380C, E410K, and D417H typically arise de novo and are associated with more severe ocular and developmental phenotypes; R262H and E410K have been reported in multiple unrelated probands. R380C patients have moderate eye phenotypes, mild to moderate intellectual disability, and corpus callosum, basal ganglia, brainstem and cerebellar vermis dysmorphology on imaging. Patients with the R262H and D417H substitutions have severe eye phenotypes, intellectual and social delays, congenital joint contractures, and peripheral neuropathy. Neuroimaging of R262H patients reveals basal ganglia and corpus callosum abnormalities [Tischfield et al., 2010]. Patients with the E410K substitution have been most deeply phenotyped. These unrelated patients have severe, bilateral, exotropic CFEOM with profound limitation of eye movements, and significant intellectual and social disabilities. Neuroimaging reveals hypoplasia to agenesis of the corpus callosum and anterior commissure, paucity of central white matter, dysgenesis of the olfactory bulbs and sulci, and hypoplastic cranial nerves. These patients also have facial dysmorphisms, Kallmann's syndrome (anosmia with hypogonadal hypogonadism), vocal cord paralysis, and develop an axonal peripheral neuropathy and cyclic vomiting [Chew et al., 2013].

None of the eight CFEOM-associated TUBB3 substitutions has been associated with cortical malformations or nystagmus, while MCD-associated substitutions have not been associated with cranial nerve dysfunction or peripheral neuropathy, suggesting that each set of mutations alters microtubule functions in a specific fashion. Here, however, we report two pathologic TUBB3 mutations that cause both CFEOM and MCD, hence blurring the distinction between them.

Materials and Methods

Research participants with complex ocular dysmotility disorders and their family members were enrolled in an ongoing research study at Boston Children's Hospital following Institutional Review Board approval and informed consent. Specific consent was also obtained for the publication of patient photographs. Detailed medical and family histories and clinical and neuroimaging data were obtained from participants and medical records. Clinical diagnostic MRIs were reviewed for each participant. Probands and their parents and siblings provided a blood and/or saliva sample from which genomic DNA was extracted using Gentra Puregene Blood Kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) or Oragene Discover OGR-500 or OGR-575 Saliva and Assisted Saliva Kits (DNA Genotek). Maternity and paternity were examined by the co-inheritance of at least 10 informative polymorphic markers, and the TUBB3 gene was sequenced in probands as previously described [Tischfield et al., 2010]. Each TUBB3 substitution was plotted on the solved protein structure for αβ-tubulin heterodimer (Protein Data Bank (PDB 1:JFF) using Pymol software (1.1r1, www.pymol.org).

Results

Genetic Findings

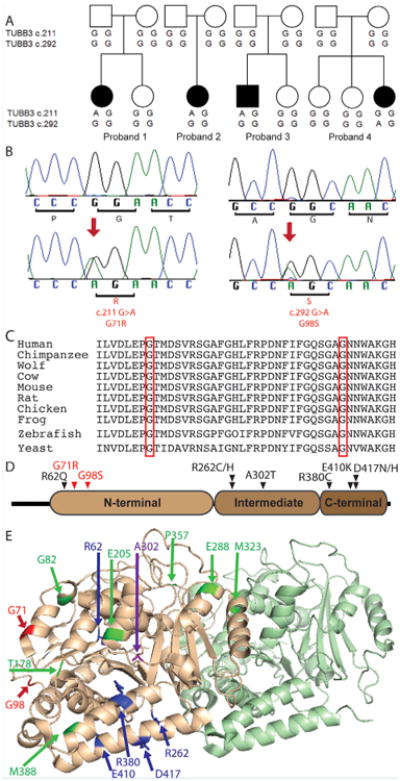

Sequencing of the TUBB3 gene in 187 research participants with CFEOM revealed two females (5 and 23 years of age) and one male (9 years of age) of European and mixed European and Native American ancestry who harbored a heterozygous TUBB3 c.211G>Amissense variant predicted to result in a p.G71R amino acid substitution. In addition, one female (2 years of age) of mixed European and African American ancestry was found to harbor a heterozygous TUBB3 c.292G>A missense variant predicted to result in a p.G98S amino acid substitution. Paternity and maternity were confirmed in all four individuals. None of the parents were affected and all had wild-type TUBB3 sequence. Thus, each of the four affected children harbored a de novo TUBB3 variant. These two missense variants were absent from greater than 1,700 control chromosomes, not present in exome databases, and the amino acid residues predicted to be altered are conserved in multiple species and among other human beta tubulin isotypes (Table I, Fig. 1A–C and data not shown).

Table I. Clinical Data.

| Individual | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Mixed European | Italian | Mixed European, Native American | Mixed European, African-American |

| Current age | 5 years | 23 years | 9 years | 2 years |

| Gender | F | F | M | F |

| Genetic findings | ||||

| Mutation | 211G>A | 211G>A | 211G>A | 292G>A |

| Amino acid substitution | G71R | G71R | G71R | G98S |

| Growth | ||||

| Birth weight | 3.97 kg (97th) | 2.81 kg (16th) | 3.86 kg (79th) | 3.52 kg (79th) |

| Birth length | 51.5 cm (90th) | 49 cm (46th) | 54.6 cm (99th) | 53.3 cm (99th) |

| Microcephaly | — | — | — | — |

| Development | ||||

| Intellectual disability | + | + | + | + |

| Social delay | Mild | Moderate | PDD-NOS | Mild |

| Hypotonia | + | + | + | + |

| Gross motor delay | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Fine motor delay | + | + | + | + |

| Ophthalmic findings | ||||

| Corrected visual acuity | 20/80, 20/80 | 20/30, 20/50 | 20/200, 20/100 | Normal for age (at 1 year of age) |

| Ptosis | Unilateral (left) | Asymmetric (right>left) | Asymmetric (right>left) | Unilateral (right) |

| Ocular alignment | Esotropia | Esotropia | Esotropia | Esotropia, Right hypotropia |

| Elevation | Severe restriction, Left eye only | Moderate restriction, Both eyes | Variable restriction, Both eyes | Severe restriction, Right eye only |

| Depression | Moderate restriction, Left eye only | Moderate restriction, Right eye only | Full | Mild restriction, Right eye only |

| Abduction | Mild restriction, Left eye only | Mild restriction, Both eyes | Moderate restriction, Left eye only | Moderate restriction, Left eye only |

| Adduction | Full | Mild restriction, Both eyes | Full | Full |

| Aberrant movements | Left eye moves while fixating with right eye | — | Marcus Gunn jaw winking, Left side | Marcus Gunn jaw winking, Right side |

| Nystagmus | Fine rotary with intermittent horizontal jerk | None | Horizontal, Pendular | Horizontal jerk, Variable amplitude |

| Pupils | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Associated findings | ||||

| Facial sensation | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Facial weakness | — | — | Mild orbicularis weakness | Mild |

| Hearing loss | Bilateral congenital (sensorineural) deafness | — | — | — |

| Vocal chord paralysis | — | — | — | — |

| Torticollis | + | + | + | + |

| Plagiocephaly | + | — | + | + |

| Contractures | Metatarsus adductus | Scoliosis, kyphosis, genu valgum, cubitus valgus, Generalized ligamentous laxity | Mild thoracic scoliosis | — |

Table detailing the genetic, growth, development, ophthalmic and associated findings for each of the four patients. NCBI reference sequence is NM_006086.

Fig 1.

Genetic findings in Probands 1–4. (A) Schematic pedigree structures of probands 1–4. Squares denote males, circles denote females, and filled symbols denote affected individuals. Under each research participant is their genotype for TUBB3 nucleotide positions c.211 and c.292. In each position, wildtype is G/G and heterozygous mutant is G/A. Note that the TUBB3 c.211G>A (pG71R) mutation arose de novo in probands 1, 2, and 3, while the TUBB3 c.292G>A (pG98S) mutations arose de novo in proband 4. (B) Chromatograms from control subjects (top), a proband harboring the c.211G>A heterozygous mutation (bottom, left), and the proband harboring the c.292G>A heterozygous mutation (bottom, right). Nucleotide substitutions are represented by the double peaks and indicated by red arrows. The corresponding normal and mutated amino acid residues are indicated with brackets underneath each codon triplet. (C) The amino acid sequence of TUBB3 is shown from residues 64 to 102 for several species; yeast has only one beta-tubulin, and thus its sequence is shown; zebrafish does not have tubulin beta 3, the sequence for tubulin beta 5 is shown. Red boxes indicate positions 71 and 98, which are conserved between species. (D) Two dimensional structure of TUBB3, showing the protein domains. The sites of the G71 and G98 amino acid substitutions are in the N-terminal domain, and are indicated in red. Sites of other CFEOM-causing substitutions are indicated in black. (E) Three dimensional structure of TUBB3, showing position of disease-causing substitutions. TUBB3 residues G71 and G98 (red) are located near the E site of the GTP binding pocket. Substitutions previously reported to be associated with CFEOM3 (blue) are most often in the C-terminal domain. Substitutions previously reported to be associated with MCD (green) are more often in residues that contact the GTP nucleotide or are at contact surfaces between the intra-and inter-heterodimers. Substitutions at A302 (purple) can cause CFEOM (A302T) or MCD (A302V).

TUBB3 residues G71 and G98 are located in the N-terminal domain of the protein, which comprises the GTP binding site and is important for heterodimer stability and longitudinal interactions within microtubule protofilaments (Fig. 1D–E) [Tischfield et al., 2011; Alushin et al., 2014]. Forces generated by the hydrolysis of GTP bound to beta-tubulin are important for the proper regulation of microtubule dynamics as they generate curved protofilament structures that are prone to catastrophes.

Perinatal Findings

All four patients were born at term and presented in the early postnatal period with unilateral (patients 1, 4) or asymmetric (2, 3) congenital ptosis. The pregnancies for Patients 2 and 4 were uncomplicated, while Patient 1 was complicated by pre-eclampsia and required vacuum assisted delivery, and Patient 3 was complicated by polyhydramnios. Patient 1 underwent a neonatal brain MRI for subgaleal hemorrhage, which revealed asymmetry of the lateral ventricles and decreased periventricular white matter. Patient 4 (G98S) underwent routine prenatal ultrasound and then follow-up fetal MRI and was found to have ventriculomegaly and brain malformations (see below). Patients 1, 3, and 4 had torticollis and plagiocephaly during infancy, treated with physical therapy and helmeting. Patient 2 had positional torticollis without plagiocephaly. Patient 1 was diagnosed with bilateral sensorineural deafness soon after birth. None had stridor or respiratory difficulties in infancy.

Growth and Development

All four patients had normal weight, length, and head circumferences (see Table I), and growth proceeded as expected.

All four patients have delays in all areas of development. All four have intellectual disabilities and have required special education services. The oldest patient, patient 2, is now 23 years of age and is not able to live or work independently. Socially, of the three G71R patients, one is diagnosed with pervasive developmental disorder (PDD-NOS), one is noted to be aggressive, and one has mild social and emotional delays. The 2-year-old patient with the G98S substitution has mild social delays (Table I). All have significant gross motor delays associated with axial hypotonia. As an example, patient two did not sit until 10 months of age, or walk until 4 years of age. All have mild to moderate fine motor delay.

Ophthalmic Findings

All four patients have CFEOM3, consisting of ptosis, moderate to severe unilateral or bilateral deficits of vertical eye movement in the affected eye(s), and milder restrictions of horizontal movements (Fig. 2). They are all esotropic in primary position. Three have nystagmus, each with a different type (detailed in Table I). Pupillary responses were normal in all four patients. The 3 patients harboring the G71R substitution have subnormal visual acuity of uncertain cause. The patient with the G98S substitution has an anomalous optic disc appearance bilaterally, with thickened, cupless appearance with abnormal vascular pattern, but normal visual acuity for age (as measured at age 1). Ocular findings are detailed in the table.

Fig 2.

Ophthalmic findings. External photographs showing the eye position of Patient 4 (G98S) at 1 year of age in five gaze positions. Of note, prior to these photos, she underwent right-sided ptosis sling and right-sided inferior rectus recession. Top row: attempted upgaze. Middle row: primary position (middle photo), and attempted right (left photo) and left (right photo) gaze. Bottom row: attempted downgaze. The right eye has ptosis and deficits of vertical movements. The left eye has an abduction deficit. She is esotropic in all gaze positions. She also has Marcus Gunn jaw winking on the right side, not pictured.

Neurological Examinations

Beyond CFEOM and plagiocephaly, no facial or other dysmorphologies were noted. No problems with olfaction were reported, although none of the four patients have had formal testing. All four patients have normal facial sensation. Patients 1 and 2 have normal facial strength and movement. Patient 3 has mild weakness of the orbicularis oculi, but otherwise normal facial strength and movement. Patient 4 (G98S) has lower face hypotonia with mild weakness, often holding her mouth open and drooling.

Patient 1 has bilateral sensorineural deafness. Hearing aids did not have an effect, and she had bilateral cochlear implants placed at age 14 months with some improvement in sound recognition. Sequencing of sensorineural deafness genes has revealed no mutations. None of the other three patients are known to have hearing loss.

Patient 4 had early dysphasia that resolved; otherwise all four patients have normal suck and swallow and full palate elevation. All four patients have axial>appendicular hypotonia, and patient 2 developed scoliosis and kyphosis at age 10 (Table I). All have normal deep tendon reflexes, sensation, and strength. None had respiratory difficulties, vocal cord paralysis, cyclic vomiting, or joint contractures, and none have required tracheostomy or developed signs of peripheral neuropathy.

Structural Brain Abnormalities

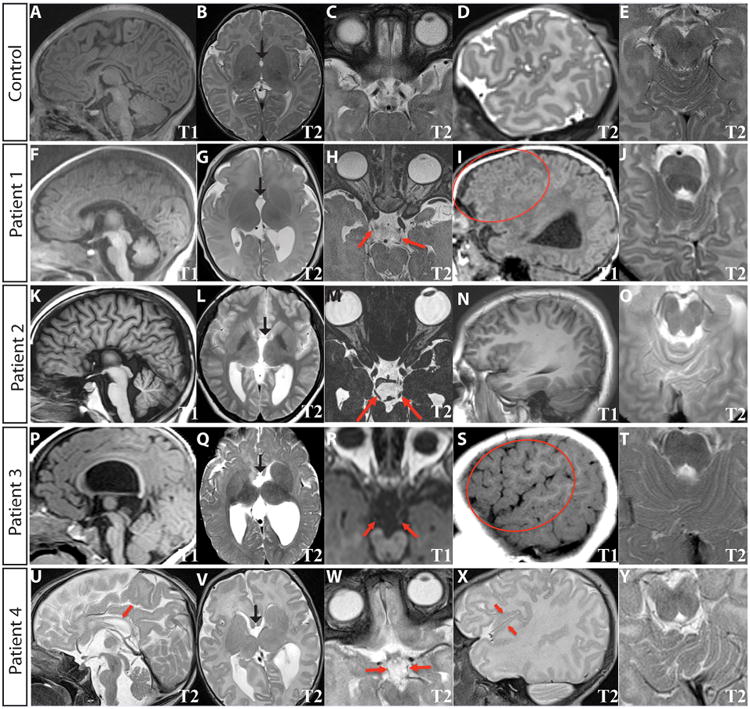

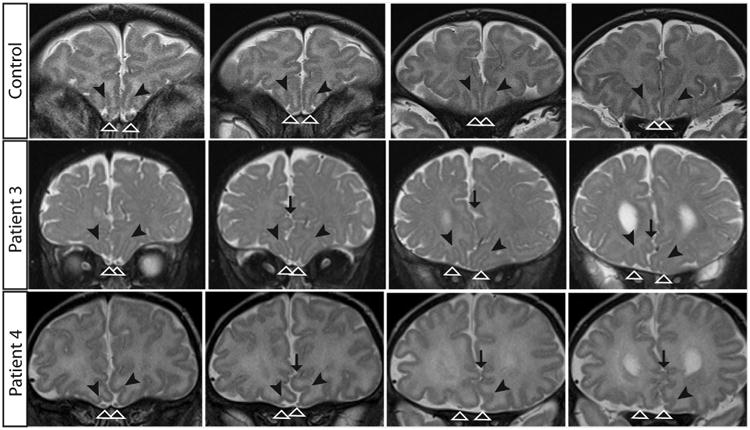

Clinical diagnostic MRIs obtained at ages 4 days (1st scan) and 8 months (2nd scan) (Patient 1), 20 years (Patient 2), 9 months (Patient 3), and 17 days (Patient 4) were reviewed (Fig. 3). Each of the patients was noted to have structural abnormalities of the brain. Most notably, all have thinning (1, 3, 4) or agenesis (2) of the corpus callosum and anterior commissure (Fig. 3F, K, P, U). Three patients (1, 3, 4) have enlarged, asymmetric ventricles with the left larger than the right, one (2) has colpocephaly, and three (1, 3, 4) have asymmetric myelination and paucity of white matter (Fig. 3G, L Q, V). The cerebral hemispheres in all four patients have frontal interdigitations raising the possibility of deficiencies in the falx cerebri (Fig. 4). The cortical gyral folding pattern is atypical, particularly in the frontal lobes (Fig. 3I, N, S, X). There are areas of increased and abnormal gyration, but no frank polymicrogyria. In three patients (1, 3, 4), the left hippocampus is incompletely rotated. The basal ganglia are also abnormally rotated, poorly separated, and globular, with hypoplasia of the left caudate body (Fig. 3G, L, Q, V). The thalami are rotated, separated, and globular. The G98S patient (4) has a rotated, hypoplastic cerebellar vermis, with dysmorphic folia crossing the midline at an oblique angle (Fig. 3Y), while the 71R patients have a normally positioned, normal sized vermis with more subtle changes in the folia (Fig. 3J, O, T). All four have asymmetrical brainstems with the left side of the pons smaller than the right, and a prominent 4th ventricle (Fig. 3F, K, P, U). Two (1, 2) have normal olfactory bulbs and sulci, but two (3, 4) show unilateral hypoplasia of the olfactory sulci (Fig. 4, black arrowheads). In three patients (1, 3, 4) the olfactory nerve has an aberrant course (Fig. 4, white arrowheads). The optic nerve appears normal in all patients, including Patient 4 who had anomalous optic nerve appearance on fundus examination. The oculomotor nerve is hypoplastic bilaterally in 3 patients (1, 3, 4), and has a curved course in patient 2 (Fig. 3H, M, R, W). In the G98S patient, who has some facial weakness, the facial nerve appears hypoplastic on the left. In patient 1, who has sensorineural deafness, there is hypoplasia or absence of the cochlear and inferior vestibular nerves on high resolution 3D SPACE imaging (images not shown). In all patients, the other cranial nerves appear grossly normal. However, thin section imaging for full assessment of cranial nerves was only available for patients 1 and 2.

Fig 3.

MRI findings. Structural brain abnormalities are associated with the TUBB3 G71R and G98S substitutions. The top panel (A–E) are images from a normal infant, (59 days of age, imaged for mild lower extremity hypertonia). Clinical MRIs were performed at age 8 months, (Patient 1, panels F-J), 20 years, (Patient 2, panels K–0), 9 months (Patient 3, panels P-T), and 17 days (Patient 4, panels U–Y). Sequence names are shown in the bottom right of each panel. A, F, K, P, U: Sagittal midline cuts show the corpus collosum is thin (F, P, U) or absent (K), and the pons is small (F, K, P, U). B, G, L, Q, V: Axial cuts through the basal ganglia and thalami show the basal ganglia and thalami are globular in shape, with the basal ganglia poorly separated and both the thalami and basal ganglia anterioromedially rotated (G, Q, V). The ventricles are enlarged, irregular in shape and asymmetric with the left larger than the right. Black arrows point to the anterior commissure (G, L, Q, V). C, H, M, R, W: Axial cuts through the midbrain show the oculomotor nerves, with arrows highlighting hypoplasia (H, R, W) or a curved course (M). D, I, N, S, X: Sagittal cuts showing dysmorphic cortical folding patterns. There is increased frontal gyration (area within the circles, I, S) in two G71 patients, while one G71 patient did not have sagittal imaging extending far enough laterally to fully assess (N). In the G98S patient (X), there is a globally disorganized gyral folding pattern and cortex within the right perisylvian fissure has a high frequency irregularity that is polymicrogyria-like (V). E, J, O, T, Y: Axial cuts through the cerebellar vermis show abnormal vermian folding patterns. In the G98S patient the vermian folding pattern was dysmorphic (Y). The G71 patients had milder abnormalities of vermian folding (J, O, T).

Fig 4.

Frontal interdigitations and abnormal olfactory pathway in Patients 3 and 4. Coronal T2 MRI images show frontal cortical interdigitations (black arrows) between hemispheres. The olfactory sulci (black arrowheads) follow an atypical course, deviating to the right. In addition, the left olfactory sulci deviates superiorly into the interhemispheric fissure in Patient 4 and the right olfactory sulci are hypoplastic in both patients. The olfactory bulbs and nerves also deviate to the right as they travel posteriorly with the right olfactory nerve and bulb more affected (white arrowheads). Each row is one patient (normal control top row, G71R middle row, G98S bottom row), images from left to right move from anterior to posterior within the brain.

Discussion

Two distinct sets of heterozygous TUBB3 missense mutations have been reported to result in two distinct human phenotypes [Poirier et al., 2010; Tischfield et al., 2010; Bahi-Buisson et al., 2014; Oegema et al., 2015]. The first results in a series of amino acid substitutions that cause MCD phenotypes similar to, but generally more mild than, patients harboring heterozygous missense mutations in TUBA1A, TUBB2B, and TUBB5. [Poirier et al., 2010; Bahi-Buisson et al., 2014; Oegema et al., 2015]. Among MCD TUBB3 patients, no genotype–phenotype correlations have been reported. The second set is associated with CFEOM in isolation, or syndromic CFEOM accompanied by additional errors in axon development and maintenance, in the absence of MCD. Specific CFEOM-causing mutations are recurrent and result in predictable genotype–phenotype correlations. They often but not exclusively alter amino acid residues located in the C-terminal domain of the protein, altering sites of binding of motor and microtubule associated proteins, and have been associated with increased microtubule stability [Tischfield et al., 2010, 2011]. Here, we have identified two new missense mutations in TUBB3 that result in a clinically recognizable syndrome that includes moderate, asymmetric or unilateral CFEOM3 with esotropia and nystagmus, severe developmental delays, and malformations of the basal ganglia, thalami, hippocampi, corpus callosum, cerebellum and brainstem, with an atypical gyral pattern in the frontal lobes. Thus, these mutations broaden the phenotypic range of the TUBB3 disorders, and blur the mechanistic distinctions between the two sets of mutations.

TUBB3 G71R and G98S, the previously reported MCD-causing, and a subset of the previously reported CFEOM3-causing amino acid substitutions all share several phenotypic features with one another and with other tubulinopathies. These include intellectual disabilities, axial hypotonia with gross motor delay, corpus callosum hypoplasia, and basal ganglia malformations. Patients harboring the TUBB3 G71R and G98S substitutions, however, also have features that are shared uniquely with only one of each phenotypic group.

The unique overlap with the previously reported MCD-associated TUBB3 mutations is mild cortical malformations. The G71R and G98S patients have a mild, frontally predominant dysgyria, very similar to that described previously in patients with MCD-associated TUBB3 mutations [Poirier et al., 2010; Bahi-Buisson et al., 2014; Oegema et al., 2015]. Interestingly, the G71R and G98S cerebellar dysplasia and brainstem hypoplasia are very similar to a recently reported series of patients harboring TUBB3, TUBB2B, and TUBA1A mutations, none of whom had CFEOM [Oegema et al., 2015]. MCD and cortical dysgyria, have not been previously found in patients harboring previously reported CFEOM-causing TUBB3 mutations, and brainstem hypoplasia and mild hypoplasia of the cerebellar vermis has been reported only with the TUBB3 R380C substitution [Tischfield et al., 2010]. Finally, G71R and G98S patients have varying forms of nystagmus, a phenotype that has been reported in four patients with three different MCD-causing TUBB3 mutations (two with “horizontal” and two with “multidirectional” nystagmus) [Poirier et al., 2010] but is not present in other patients with CFEOM3-causing TUBB3 mutations. None of the patients have foveal hypoplasia or other exam findings that might explain the nystagmus, and its etiology remains unexplained.

The unique overlap with the previously reported CFEOM-associated TUBB3 mutations is CFEOM. Notably, the manifestations of these patients' CFEOM relative to their degree of intellectual and social dysfunction differ from previously reported CFEOM-associated TUBB3 patients. They have asymmetric involvement, esotropia, and moderate limitation of eye movements, while previously reported TUBB3 substitutions causing unilateral or asymmetric CFEOM cause either isolated CFEOM or CFEOM associated with mild additional neurological findings.

Despite the similar levels of intellectual and social disabilities between the G71R and G98S patients reported here and the E410K, R262H, and D417H patients reported previously [Tischfield et al., 2010; Chew et al., 2013], none of the additional features associated with the reported substitutions (facial dysmorphisms, Kallmann's syndrome, vocal cord paralysis, axonal peripheral neuropathy, and cyclic vomiting or joint contractures) were found in patients with the G71R and G98S substitutions. Social delays are seen in the G98S and G71R patients, and at least one meets diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder, similar to the E410K, R262H, and D417H substitutions. By contrast, social delays have not been reported in patients with MCD-associated TUBB3 mutations.

One G71R patient has bilateral sensorineural hearing loss associated with hypoplasia or absence of the cochlear and inferior vestibular nerves bilaterally. It is unclear if this is related to her TUBB3 mutation, as hearing loss has not been reported in any other patients with TUBB3 mutations, either associated with CFEOM or associated with MCD [Poirier et al., 2010; Tischfield et al., 2010; Chew et al., 2013; Oegema et al., 2015]. The identification of additional patients harboring this mutation will be necessary to determine if hearing loss and cranial nerve VIII abnormalities are part of the syndrome.

TUBB3 consists of N-terminal, intermediate, and C-terminal domains. The N-terminal domain forms the GTP binding site, and interactions between the N-terminal and intermediate domains are involved in heterodimer stability and longitudinal and lateral interactions between protofilaments [Lowe et al., 2001; Poirier et al., 2010; Tischfield et al., 2011]. The C-terminal domain is involved in interactions with motor proteins and microtubule-associated proteins. Mutations associated with MCD (green arrows in Fig. 1) are more often in residues that contact the GTP nucleotide or are located at intra-and inter-heterodimer interfaces, and perturb heterodimer formation, resulting in decreased microtubule stability [Poirier et al., 2010; Tischfield et al., 2011]. By contrast, mutations associated with CFEOM3 are most often in the C-terminal domain (blue arrows in Figure 1) and may disrupt interactions with motor proteins and microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs). In yeast, these mutations dampen microtubule dynamics and stabilize the microtubule cytoskeleton [Tischfield et al., 2010].

TUBB3 residues G71 and G98, altered in the patients presented in this report, are located in the N-terminal domain of the protein, near the E site of the GTP binding pocket. Furthermore, G98 is in the T3 Loop, which is predicted to form direct contacts with the GTP nucleotide. As can be seen in Figure 1, the G71 and G98 residues are spatially distinct from residues previously reported as altered in MCD and in CFEOM, but appear more similar in their location to those associated with MCD. Future experiments could determine how these two unique mutations alter heterodimer formation, incorporation, microtubule dynamics, and motor protein transport.

The G71R and G98S patients further expand the range of phenotypes seen in TUBB3 mutations, and are another example of the growing genotype–phenotype correlations that can be recognized as a result of missense mutations within this gene. They also complicate our understanding of the underlying mechanisms that lead to these two phenotypes. Future genetic testing of rare pedigrees may reveal additional TUBB3 mutations that further define a continuum between the CFEOM- and MCD-phenotypes. Notably, we previously reported a family with a TUBB2B mutation that caused both CFEOM and polymicrogyria [Cederquist et al., 2012]. Although we did not identify additional TUBB2B mutations in our CFEOM cohort, mutations in other tubulin isotypes may be a rare cause of CFEOM.

Defining this syndrome provides the ability to recognize it clinically, and can thereby enhance the accuracy of genetic testing and counseling. In each of the patients presented here, this mutation arose de novo in the affected individual, so families could be reassured that the chance of recurrence in subsequent offspring is extremely low. Overall, we recommend that patients with developmental delay and any paralytic eye movement deficits or ptosis be screened for TUBB3 mutations. Identifying such mutations allows clinicians to provide prognostic information and anticipate and intervene in potential future problems.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the families for their participation, and Dr. Monte D. Mills, MD, MS, and Karen Karp, BSN of the Division of Ophthalmology, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, for referring one of the patients for our study, and providing clinical information. E.C.E. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator.

Grant sponsor: National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health; Grant number: R01EY12498; Grant sponsor: Boston Children's Hospital Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center; Grant number: HD018655; Grant sponsor: Harvard-Vision Clinical Scientist Development Program Research; Grant number: 5K12EY016335; Grant sponsor: Knights Templar Eye Foundation; Grant sponsor: Children's Hospital Ophthalmology Foundation; Grant sponsor: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; Grant number: 5K12NS049453-09.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none.

References

- Alushin GM, Lander GC, Kellogg EH, Zhang R, Baker D, Nogales E. High-resolution microtubule structures reveal the structural transitions in alphabeta-tubulin upon GTP hydrolysis. Cell. 2014;157:1117–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahi-Buisson N, Poirier K, Fourniol F, Saillour Y, Valence S, Lebrun N, Hully M, Bianco CF, Boddaert N, Elie C, Lascelles K, Souville I, Consortium LIT, Beldjord C, Chelly J. The wide spectrum of tubulinopathies: What are the key features for the diagnosis? Brain. 2014;137:1676–1700. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederquist GY, Luchniak A, Tischfield MA, Peeva M, Song Y, Menezes MP, Chan WM, Andrews C, Chew S, Jamieson RV, Gomes L, Flaherty M, Grant PE, Gupta ML, Jr, Engle EC. An inherited TUBB2B mutation alters a kinesin-binding site and causes polymicrogyria, CFEOM and axon dysinnervation. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:5484–5499. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Desai J, Miranda CJ, Duncan JS, Qiu W, Nugent AA, Kolpak AL, Wu CC, Drokhlyansky E, Delisle MM, Chan WM, Wei Y, Propst F, Reck-Peterson SL, Fritzsch B, Engle EC. Human CFEOM1 mutations attenuate KIF21A autoinhibition and cause oculomotor axon stalling. Neuron. 2014;82:334–349. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew S, Balasubramanian R, Chan WM, Kang PB, Andrews C, Webb BD, MacKinnon SE, Oystreck DT, Rankin J, Crawford TO, Geraghty M, Pomeroy SL, Crowley WF, Jr, Jabs EW, Hunter DG, Grant PE, Engle EC. A novel syndrome caused by the E410K amino acid substitution in the neuronal beta-tubulin isotype 3. Brain. 2013;136:522–535. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeber CP, Hunter DG, Engle EC. The genetic basis of incomitant strabismus: Consolidation of the current knowledge of the genetic foundations of disease. Semin Ophthalmol. 2013;28:427–437. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2013.825288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidary G, Engle EC, Hunter DG. Congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles. Semin Ophthalmol. 2008;23:3–8. doi: 10.1080/08820530701745181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J, Li H, Downing KH, Nogales E. Refined structure of alpha beta-tubulin at 3.5 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2001;313:1045–1057. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oegema R, Cushion TD, Phelps IG, Chung SK, Dempsey JC, Collins S, Mullins JG, Dudding T, Gill H, Green AJ, Dobyns WB, Ishak GE, Rees MI, Doherty D. Recognisable cerebellar dysplasia associated with mutations in multiple tubulin genes. Hum Mol Genet. 2015:1–13. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirier K, Saillour Y, Bahi-Buisson N, Jaglin XH, Fallet-Bianco C, Nabbout R, Castelnau-Ptakhine L, Roubertie A, Attie-Bitach T, Desguerre I, Genevieve D, Barnerias C, Keren B, Lebrun N, Boddaert N, Encha-Razavi F, Chelly J. Mutations in the neuronal ss-tubulin subunit TUBB3 result in malformation of cortical development and neuronal migration defects. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:4462–4473. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischfield MA, Baris HN, Wu C, Rudolph G, Van Maldergem L, He W, Chan WM, Andrews C, Demer JL, Robertson RL, Mackey DA, Ruddle JB, Bird TD, Gottlob I, Pieh C, Traboulsi EI, Pomeroy SL, Hunter DG, Soul JS, Newlin A, Sabol LJ, Doherty EJ, de Uzcategui CE, de Uzcategui N, Collins ML, Sener EC, Wabbels B, Hellebrand H, Meitinger T, de Berardinis T, Magli A, Schiavi C, Pastore-Trossello M, Koc F, Wong AM, Levin AV, Geraghty MT, Descartes M, Flaherty M, Jamieson RV, Moller HU, Meuthen I, Callen DF, Kerwin J, Lindsay S, Meindl A, Gupta ML, Jr, Pellman D, Engle EC. Human TUBB3 mutations perturb microtubule dynamics, kinesin interactions, and axon guidance. Cell. 2010;140:74–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischfield MA, Cederquist GY, Gupta ML, Jr, Engle EC. Phenotypic spectrum of the tubulin-related disorders and functional implications of disease-causing mutations. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011;21:286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Andrews C, Chan WM, McKeown CA, Magli A, de Berardinis T, Loewenstein A, Lazar M, O'Keefe M, Letson R, London A, Ruttum M, Matsumoto N, Saito N, Morris L, Del Monte M, Johnson RH, Uyama E, Houtman WA, de Vries B, Carlow TJ, Hart BL, Krawiecki N, Shoffner J, Vogel MC, Katowitz J, Goldstein SM, Levin AV, Sener EC, Ozturk BT, Akarsu AN, Brodsky MC, Hanisch F, Cruse RP, Zubcov AA, Robb RM, Roggenkaemper P, Gottlob I, Kowal L, Battu R, Traboulsi EI, Franceschini P, Newlin A, Demer JL, Engle EC. Heterozygous mutations of the kinesin KIF21A in congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles type 1 (CFEOM1) Nat Genet. 2003;35:318–321. doi: 10.1038/ng1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Hunter DG, Andrews C, Engle EC. A novel KIF21A mutation in a patient with congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles and Marcus Gunn jaw-winking phenomenon. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1254–1259. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.9.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]