Abstract

Purpose: Studies have found disparities in psychological distress between lesbian and gay cancer survivors and their heterosexual counterparts. Exercise and partner support are shown to reduce distress. However, exercise interventions haven't been delivered to lesbian and gay survivors with support by caregivers included.

Methods: In this pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT), ten lesbian and gay and twelve heterosexual survivors and their caregivers were randomized as dyads to: Arm 1, a survivor-only, 6-week, home-based, aerobic and resistance training program (EXCAP©®); or Arm 2, a dyadic version of the same exercise program involving both the survivor and caregiver. Psychological distress, partner support, and exercise adherence, were measured at baseline and post-intervention (6 weeks later). We used t-tests to examine group differences between lesbian/gay and heterosexual survivors and between those randomized to survivor-only or dyadic exercise.

Results: Twenty of the twenty-two recruited survivors were retained post-intervention. At baseline, lesbian and gay survivors reported significantly higher depressive symptoms (P = .03) and fewer average steps walked (P = .01) than heterosexual survivors. Post-intervention, these disparities were reduced and we detected no significant differences between lesbian/gay and heterosexual survivors. Participation in dyadic exercise resulted in a significantly greater reduction in depressive symptoms than participation in survivor-only exercise for all survivors (P = .03). No statistically significant differences emerged when looking across arm (survivor-only vs. dyadic) by subgroup (lesbian/gay vs. heterosexual).

Conclusion: Exercise may be efficacious in ameliorating disparities in psychological distress among lesbian and gay cancer survivors, and dyadic exercise may be efficacious for survivors of diverse sexual orientations. Larger trials are needed to replicate these findings.

Key words: : cancer, caregivers, exercise, health disparities, oncology, sexual orientation

Introduction

To date, lesbian and gay cancer survivors have been largely invisible in the cancer control literature.1,2 Studies of the needs of diverse populations of cancer patients and survivors, including research on side effects of treatment and long-term health outcomes post cancer, have rarely acknowledged the subject of sexual orientation.3–5 The few studies that have focused on lesbian and gay cancer control issues have introduced the possibility that physical and mental health disparities affect lesbian and gay cancer survivors even after the cessation of cancer treatments.6,7

Distress, a negative psychological reaction to the cancer experience, is among the most common side effects cited by cancer survivors of any sexuality,8–10 and is linked to increased morbidity11 and mortality.12 Psychological distress appears to be more common among lesbian and gay survivors than among heterosexual survivors (with odds ratios > 1.7),13,14 possibly as a result of exposure to minority stress and discrimination based on sexual orientation.1,15 Post-cancer, gay male survivors report mental health difficulties and a high level of fear about cancer recurrence.16,17 Some studies indicate that subgroups of lesbian survivors report more anxiety and more depression than heterosexual women,6,18 while other studies have shown minimal difference between these groups.19 Given rates of distress among lesbian and gay survivors and the link between distress, morbidity, and mortality, interventions targeting distress among lesbian and gay cancer survivors are urgently needed. There is also a need for interventions that take into account the sociocultural context of these populations.20,21

Previous studies have shown that exercise, including walking and resistance training, is safe, well tolerated, and reduces distress in heterosexual cancer survivors.22–25 Exercise can reduce psychological distress by facilitating engagement in reinforcing behaviors (also known as behavioral activation) and by increasing self-efficacy, factors that have been shown to improve psychological well being.26–28 Exercise may also be more palatable than weekly psychotherapy for some cancer survivors.28,29 For lesbian and gay cancer survivors specifically, rates of engagement in exercise may be lower than rates among heterosexual survivors.13 Tailoring an exercise intervention to lesbian and gay cancer survivors would involve both being responsive to sexual minority stressors and increasing rates of engagement in physical activity.

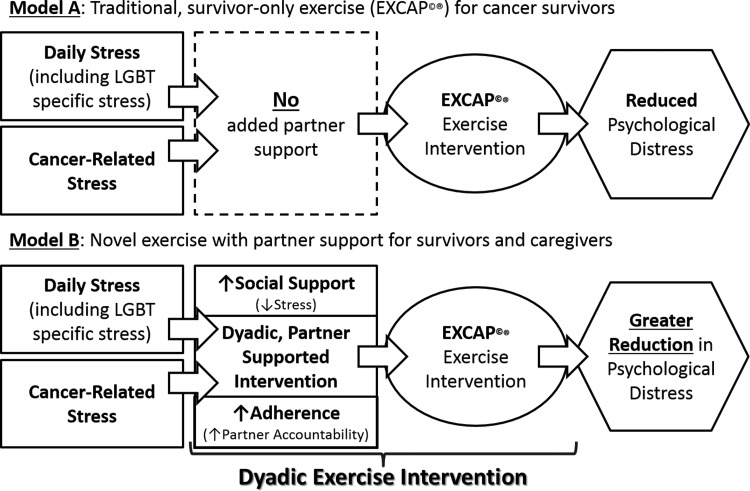

Partner support has been directly linked to reductions in sexual minority-specific stress among lesbian and gay adults.30,31 Support from caregivers is viewed as particularly important to lesbian and gay cancer survivors around the time of diagnosis,32 and can reduce the impact of minority stressors.30 In the context of exercise, two previous intervention trials have shown that exercise interventions incorporating support from a caregiver may increase adherence and produce significant improvements in clinical outcomes among cancer survivors.33,34 However, neither study compared the efficacy of a partner-assisted exercise intervention to a survivor-only intervention, nor did either study recruit lesbian and gay survivors. Thus, while preliminary evidence indicates that including caregivers in exercise interventions may be effective, no randomized controlled trials (RCT) have evaluated the efficacy of a partner-assisted exercise intervention in reducing psychological distress among lesbian and gay cancer survivors.35 We are guided in designing a dyadic, partner-assisted intervention by theories of interpartner social support and social control, wherein partners both support one another (increasing perception of social support)33 and hold one another accountable (increasing intervention adherence)35–37 while enacting behavior changes.36–38 (See Figure 1.)

FIG. 1.

Models for survivor-only and dyadic exercise interventions.

In the current pilot study, we tested the feasibility of using exercise to address disparities in psychological distress experienced by lesbian and gay cancer survivors. In addition, we were interested in examining whether including interpartner factors, namely partner support and accountability, would improve the effect of the intervention on distress outcomes. Our hypotheses were: (1) that lesbian and gay cancer survivors would report higher psychological distress, defined as symptoms of depression and anxiety, than heterosexual survivors; (2) that an exercise intervention would serve to reduce these disparities; and (3) that an intervention including partner support would result in greater reductions in distress, greater increases in reported partner support, and greater increases in exercise adherence than an intervention for the survivor only.

Methods

Participants

We recruited 10 lesbian and gay cancer survivors and their 10 caregivers, as well as 12 heterosexual survivors and their 12 caregivers to this pilot, two-arm, RCT. To be eligible to participate, cancer survivors must have been diagnosed with cancer (any site except squamous or basal cell skin cancers) and have completed surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy within the last 60 months. All survivors recruited to the study were asked to nominate a caregiver, broadly defined as anyone who provided emotional or tangible support during the cancer experience. All participants (survivors and caregivers) could have had no medical contraindications for participating in a low-to-moderate intensity exercise program, as verified by their primary physician. No further restriction was placed on caregivers in terms of type or duration of their relationship with the cancer survivor. Analyses herein focus solely on the cancer survivors.

We used targeted recruitment strategies to ensure a sample of lesbian and gay cancer survivors. Oncologists and nurses at the Wilmot Cancer Center at the University of Rochester referred self-identified lesbian and gay cancer survivors to our study, and we conducted outreach to local groups serving the lesbian and gay communities. Finally, we relied on word-of-mouth, whereby previously recruited participants referred other survivors to our study. Because of the small sample size, lesbian and gay cancer survivors were analyzed together as one group. To recruit heterosexual survivors, oncologists and nurses at the Wilmot Cancer Center referred eligible potential participants to our study. The institutional review board at the University of Rochester approved all study procedures, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Procedures

All assessment procedures were conducted in a controlled laboratory environment under the supervision of an American College of Sports Medicine Certified Exercise PhysiologistSM and a clinical psychologist. Cancer survivors and caregivers attended assessments as a dyad when possible. Following informed consent, participants (cancer survivors and caregivers) were given a pedometer and a series of daily diary sheets to track their number of steps walked per day. After tracking steps for seven days, participants returned to the lab for a baseline assessment, during which both cancer survivors and caregivers completed a battery of psychosocial questionnaires separately and in private rooms.

Survivors and caregivers were then randomized as a dyad to one of two intervention arms. Arm 1 was a survivor-only exercise intervention delivered to cancer survivors alone; instructions, a pedometer, and an exercise kit for a home-based walking and resistance exercise program were given to survivors, while caregivers were instructed not to change their exercise behavior in any way. Arm 2 was a dyadic exercise intervention delivered to cancer survivors and their caregivers together; instructions, pedometers, and exercise kits were given to both cancer survivors and caregivers together. Participants returned home and those randomized to receive the exercise intervention completed the intervention procedures on their own over the course of six weeks. A member of the study team contacted participants each week to check on intervention adherence and troubleshoot any issues with the exercise prescription. For those in Arm 1, this contact involved only the survivor, while the survivor and caregiver were contacted together in Arm 2.

During the sixth and final week of intervention, caregivers in Arm 1 were given pedometers to track their steps. Participants then returned to the laboratory and completed a post-intervention assessment. Procedures for the post-intervention assessment mirrored those of the baseline assessment. Caregivers in Arm 1 received exercise instructions and an exercise kit following the post-intervention assessment.

Interventions

The exercise intervention used, EXCAP©® (Exercise for Cancer Patients), is a standardized, daily, 6-week, home-based, progressive exercise program. EXCAP©® has proven safe to administer and efficacious for a range of cancer patients and survivors.39 EXCAP©® consists of a walking prescription and a therapeutic resistance band exercise prescription, designed to provide moderately intense aerobic and resistance exercise 7 days a week. Participants were instructed to increase progressively from their baseline number of steps walked and sets and repetitions of resistance exercise over the 6-week intervention period. Exercise instructions were tailored to participants' level of fitness and the intervention was conducted in the participants' homes or in another participant-selected environment.

The dyadic intervention arm used the EXCAP©® intervention along with a dyadic component informed by social support and social control theories. Following exercise instruction, a member of the research team discussed barriers to exercising and ways to overcome these barriers and remain adherent to exercise with both the cancer survivor and the caregiver. The survivor/caregiver dyad was also invited to discuss stressors that arose in the context of cancer care. To bolster both support and accountability, exercise was reinforced as a shared behavior in which the dyad could engage to show support for one another and thereby reduce stress.40–42

Measures

Demographic and clinical variables

A single demographic questionnaire assessed age, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, education, employment status, and marital status. The cancer survivor was asked about type of cancer, stage, and type of treatment.

Psychological distress

The primary outcome, was assessed with two measures. First, symptoms of depression were assessed with the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). The CES-D is a 20-item self-report depression scale developed and validated for use with a variety of populations.43 It has been used to measure depression in cancer populations and demonstrates excellent reliability and validity.44 Second, anxiety symptoms were measured using the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI Form Y-1), State Form. This self-report questionnaire consists of 20 short statements that people may use to describe their feelings. The STAI has demonstrated very good to excellent internal consistency coefficients, test/retest reliability, and concurrent, construct, convergent and divergent validity.45,46

Partner support

Partner support was assessed with the Dyadic Support Questionnaire (DSQ), an 18-item survey based on four functions of social support (emotional, appraisal, instrumental, and informational support). Nine items assessing received social support, that is, support provided by the partner, were analyzed for this study. Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficients and test-retest reliability coefficients for this measure range from very good to excellent.47

Exercise adherence

Exercise adherence was assessed by examining the average number of steps that participants self-reported walking daily in the week before the baseline assessment (i.e., before the intervention started) and in the week before the post-intervention assessment (i.e., the sixth week of being in the study).

Data Analysis

Analyses were performed with SPSS (version 22.0; IBM, Chicago, IL), using two-tailed tests with P ≤ .05 as the criterion for statistical significance. Because of our extremely small sample size (n = 10 or n = 5 per cell depending on the test), we opted to conduct independent sample t-tests to evaluate our hypotheses.48,49 First, descriptive statistics were calculated to examine demographic characteristics of the participants. To address hypotheses 1 and 2, we compared psychological distress, partner support, and average steps between lesbian/gay vs. heterosexual survivors at baseline and post-intervention using independent sample t-tests. To address hypothesis 3, we calculated change scores, subtracting baseline score from post-intervention score for depression, anxiety, partner support, and average steps walked. We compared the effect of the individual vs. the dyadic intervention on all outcomes for all cancer survivors (n = 10 per group) and all caregivers (n = 10 per group). Then we compared the effect of the dyadic vs. the individual intervention on all outcomes for LGBT cancer survivors (n = 5 per group) and heterosexual cancer survivors (n = 5–7 per group). Because of the very small sample size and the relatively large number of tests conducted with no adjustment for multiplicity, all results should be interpreted with caution and taken as preliminary.

Results

Recruitment, retention, and intervention delivery

With regards to recruitment, 63 potentially eligible cancer survivors were contacted about participation in this study. We contacted 25 LGBT survivors and 38 heterosexual survivors. Ten were contacted via letter only, while the remaining 53 spoke to a member of the research team either on the phone or at a clinic appointment. Of these 53 eligible survivors, 22 participated in the study; five reported they had “too much going on” to participate in a research study; two reported they did not have a caregiver they could bring into the study; and the remaining 24 expressed general disinterest in participating.

With regards to retention, two heterosexual participants, both randomized to the survivor-only intervention, withdrew from the study before the post-intervention assessment. One withdrew due to caregiver unavailability and one withdrew as a result of cancer recurrence and initiating treatment. One lesbian participant chose not to complete the CES-D at the baseline assessment, but did complete this questionnaire at post-intervention. Participants completed all other assessment procedures. With regards to intervention contamination, we examined change in self-reported steps among caregivers randomized to the dyadic vs. survivor-only intervention. Caregivers in the dyadic intervention increased their steps an average of 851.00 per day (SE = 1294.22), while those in the survivor-only intervention increased their steps only 89.14 per day (SE = 779.29). This difference, while favoring the dyadic condition where caregivers were instructed to exercise, was not statistically significant.

Participant characteristics

See Table 1 for demographic details. The mean age of all cancer survivors in this sample was 56 years (range 27 to 71; standard error of the mean [SE] = 2.5). Over half (63.6%, n = 14) reported that they were female; none of the participants reported a transgender identity. The lesbian/gay group was evenly split between lesbian (n = 5) and gay (n = 5) participants. The sample was 95.5% (n = 21) non-Hispanic white; 4.5% (n = 1) reported a Hispanic/Latino origin. The modal level of education was graduate training or a graduate degree (59.1%, n = 13); over half of the sample (54.5%, n = 12) was employed full or part time. All cancer survivors (n = 22) reported being married or in a long-term relationship. Survivors reported a range of cancer diagnoses: 9 breast; 2 each of prostate, rectal, and testicular; and 1 each of esophageal, ovarian, pancreatic, sinus, stomach, thyroid, and tongue. On average, survivors had completed treatment 61 (SE = 14.9) weeks ago and all survivors had undergone some form of primary treatment for their cancer.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Current Sample

| Characteristic | Full Sample n = 22 | Lesbian/Gay n = 10 | Heterosexual n = 12 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Mean (SE) | 56 (2.5) | 54 (4.8) | 58 (2.3) |

| Gender, n(%) | |||

| Female | 14 (63.6) | 5 (50.0) | 9 (75.0) |

| Male | 8 (36.4) | 5 (50.0) | 3 (25.0) |

| Race/Ethnicity, n(%) | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 (4.5) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 21 (95.5) | 9 (90.0) | 12 (100.0) |

| Education, n(%) | |||

| Some college | 5 (22.7) | 3 (30.0) | 2 (16.7) |

| Bachelor's degree | 4 (18.2) | 2 (20.0) | 2 (16.7) |

| Graduate degree or training | 13 (59.1) | 5 (50.0) | 8 (66.7) |

| Employment Status, n(%) | |||

| Employed part- or full-time | 12 (54.5) | 6 (60.0) | 6 (50.0) |

| Retired | 5 (22.7) | 2 (20.0) | 3 (25.0) |

| Sick or disability leave | 5 (22.7) | 2 (20.0) | 3 (25.0) |

| Marital Status, n(%) | |||

| Married | 20 (90.2) | 8 (80.0) | 12 (100.0) |

| Long-term relationship | 2 (9.1) | 2 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cancer Stage, n(%) | |||

| I A-B | 9 (40.9) | 4 (40.0) | 5 (41.7) |

| II A-B | 5 (22.7) | 2 (20.0) | 3 (25.0) |

| III A-C | 7 (31.8) | 3 (30.0) | 4 (33.3) |

| IV A | 1 (4.5) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Weeks Since Treatment, Mean (SE) | 61 (14.9) | 55 (16.3) | 67 (25.7) |

| Previous Surgery, n(%) | 20 (70.6) | 9 (90.0) | 11 (91.7) |

| Previous Chemotherapy, n(%) | 11 (14.7) | 4 (40.0) | 7 (58.3) |

| Previous Radiotherapy, n (%) | 9 (35.3) | 4 (40.0) | 5 (41.7) |

Ninety-five percent of survivors (n = 21) named their spouse or partner as their caregiver; one heterosexual female survivor named her heterosexual daughter. This meant that 50% of caregivers were of the same reported gender as the survivor. Caregivers were not significantly different from survivors in mean age (M = 24 years, SE = 2.6); all were non-Hispanic white; and 73% (n = 16) were employed full or part time.

Psychological distress, partner support, and exercise in lesbian/gay, and heterosexual survivors

Means for depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, partner support, and average daily steps for lesbian/gay and heterosexual survivors at baseline are in Table 2. Lesbian/gay and heterosexual survivors differed at baseline in depressive symptoms, with lesbian/gay survivors reporting more depressive symptoms than their heterosexual counterparts (Cohen's d = 1.12, P = .03). Lesbian/gay survivors also reported walking fewer steps at baseline than heterosexual survivors (Cohen's d = −1.36, P = .01). The analysis revealed no clear evidence of differences in anxiety symptoms or report of partner support at baseline between lesbian/gay and heterosexual survivors. At post-intervention, no conclusive differences were detected between lesbian/gay and heterosexual survivors on any variables of interest.

Table 2.

Baseline (n = 22) and Post-Intervention (n = 20) Means, Standard Errors, and t-Tests for Lesbian/Gay vs. Heterosexual Survivors and for Survivors Randomized to Survivor-Only vs. Dyadic Exercise

| Lesbian/Gay | Heterosexual | Survivor-Only | Dyadic | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 10b | n = 12c | n = 12c | n = 10 | ||||||||

| Measurea | Timepoint | Mean | (SE) | Mean | SE | t-test P | Mean | (SE) | Mean | SE | t-test P |

| CES-D | Baseline | 12.43 | (3.25) | 6.25 | (0.84) | .03* | 8.57 | (3.60) | 8.50 | (1.10) | .98 |

| Post | 8.40 | (2.69) | 5.89 | (1.61) | .45 | 8.90 | (2.69) | 5.33 | (1.47) | .28 | |

| Change | −2.57 | (2.38) | 0.00 | (1.50) | .36 | 2.00 | (1.25) | −3.56 | (1.82) | .03* | |

| STAI | Baseline | 30.50 | (2.73) | 25.75 | (1.90) | .16 | 27.60 | (2.87) | 28.17 | (2.00) | .87 |

| Post | 32.33 | (3.06) | 26.70 | (2.37) | .16 | 27.80 | (2.58) | 31.11 | (3.08) | .42 | |

| Change | 2.33 | (2.15) | 0.70 | (1.66) | .55 | 0.20 | (1.86) | 2.89 | (1.86) | .32 | |

| DSQ | Baseline | 38.50 | (1.93) | 41.50 | (1.46) | .22 | 40.10 | (1.52) | 40.17 | (1.86) | .98 |

| Post | 35.00 | (2.79) | 41.40 | (1.28) | .06 | 37.20 | (2.33) | 39.20 | (2.46) | .56 | |

| Change | −3.50 | (1.07) | −1.30 | (0.96) | .14 | −2.90 | (1.03) | −1.90 | (1.10) | .52 | |

| Steps | Baseline | 4108.43 | (668.49) | 7745.06 | (1065.68) | .01* | 4896.84 | (634.84) | 6956.64 | (1295.59) | .17 |

| Post | 5461.40 | (1183.99) | 8022.33 | (865.63) | .10 | 7317.07 | (1040.15) | 6532.51 | (1184.30) | .63 | |

| Change | 1914.22 | (1191.47) | 591.70 | (1042.86) | .42 | 2015.14 | (1115.79) | 301.86 | (1057.00) | .29 | |

CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; DSQ, Dyadic Support Questionnaire.

One lesbian/gay participant opted not to complete the CES-D at baseline but did complete this measure at post-intervention. Means and change scores reflect this.

Two heterosexual participants, both randomized to the survivor-only arm, withdrew from the study before the post-intervention assessment. Means and change scores reflect this.

Statistically significant at the .05 level.

Change in distress, partner support, and exercise by intervention type

Looking across the whole sample (i.e., both lesbian/gay and heterosexual survivors), those randomized to the dyadic intervention reported a significantly greater decrease in depressive symptoms than those randomized to the survivor-only intervention (Cohen's d = 1.26, P = .03). No differences were detected in change in anxiety symptoms, partner support, or number of steps walked between the two arms. We detected no statistically significant differences in change scores between lesbian/gay survivors randomized to the dyadic intervention vs. heterosexual survivors randomized to the dyadic intervention, and no statistically significant differences between lesbian/gay survivors randomized to the survivor-only intervention vs. heterosexual survivors randomized to the survivor-only intervention.

Discussion

The results of the current, preliminary study indicate that it is feasible to recruit lesbian, gay, and heterosexual survivors and their caregivers to an intervention trial. In addition, exercise may be an effective intervention for addressing disparities in psychological distress among lesbian and gay cancer survivors. In this small pilot study, we recruited and randomized ten lesbian and gay survivors (out of 25 approached) and 12 heterosexual cancer survivors (out of 38 approached); twenty of the 22 survivors and their caregivers were retained post-intervention. Cancer survivors were randomized either to survivor-only exercise or to dyadic exercise including a caregiver. At baseline (before intervention), lesbian and gay cancer survivors reported more depressive symptoms than their heterosexual counterparts. Regardless of whether they engaged in survivor-only exercise or dyadic exercise with a caregiver, at post-intervention our analyses did not detect differences in depressive symptoms between lesbian/gay and heterosexual cancer survivors. Exercise has been shown to reduce distress among heterosexual survivors; this is the first study to indicate that it might be efficacious in addressing distress among lesbian and gay survivors as well.

In addition, the current study indicates that dyadic exercise (i.e., including a caregiver) may reduce depressive symptoms among lesbian, gay, and heterosexual cancer survivors, relative to exercise for the survivor alone. We examined whether the effect of dyadic exercise differed for lesbian/gay and heterosexual survivors and found no clear evidence of an effect. These analyses involved very small sample sizes (n = ∼5), however, and should be treated as exploratory.

At baseline, lesbian and gay cancer survivors reported walking fewer steps, on average, than their heterosexual counterparts. At post-intervention, this difference was non-significant, regardless of randomization to survivor-only or dyadic exercise; engaging lesbian and gay cancer survivors in exercise can perhaps address observed disparities in physical activity. Lesbian and gay survivors also reported non-significantly lower partner support (on the Dyadic Support Questionnaire) than heterosexual survivors at both baseline and post-intervention. Though intervention contamination appeared to be low, with very little increase in steps walked among caregivers in the survivor-only condition, we found limited support for the role of dyadic intervention in increasing partner support and exercise adherence among survivors.

Given the pilot nature of the current study, all results need to be replicated in a larger, Phase II or III trial, with the goal of elaborating on interpartner models (like social control theory) that have yet to be validated among LGBT survivors and their caregivers. A larger trial could also test mediational hypotheses regarding the role of change in social support and control factors (i.e., partner support and exercise adherence) in predicting change in psychological distress among lesbian, gay, and heterosexual survivors. Future studies should also focus on recruiting bisexual and transgender cancer survivors, so as to characterize cancer-related symptoms and side effects across the spectrum of sexual and gender minorities. Finally, future and better-powered studies should focus on dyadic exercise as an intervention to address psychological distress among caregivers of lesbian and gay cancer survivors, as little research has focused on the psychological needs of this population.

Limitations

Findings of the current study should be treated as preliminary and must be viewed in the light of several limitations. First, this was a pilot, Phase I trial, and hence had a limited sample size. The study should be considered underpowered and results interpreted with caution. Second, due to the small sample size, lesbian and gay survivors were treated as a single group; similarly, female and male cancer survivors were treated as a single group. Future, larger studies should examine these sub-groups separately. This study was conducted in a single geographic region among self-identified lesbian and gay cancer survivors and among survivors who agreed to take part in an exercise intervention; almost all were non-Hispanic white and highly educated. These factors limit the generalizability of our findings. Finally, we analyzed only two time points: baseline and post-intervention. Future studies should include additional time points and additional mechanistic measurements (e.g., inflammatory biomarkers) in order to establish pathways by which exercise can affect distress among lesbian, gay, and heterosexual survivors.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, the current study is the first, to our knowledge, to deliver an exercise intervention to lesbian, gay, and heterosexual cancer survivors. This pilot trial offers preliminary indication of the efficacy of exercise in addressing disparities in depressive symptoms among lesbian and gay survivors, and preliminary indication of the efficacy of dyadic exercise in reducing depressive symptoms among diverse cancer survivors. We hope this will serve as the first of many cancer control intervention trials focusing on the needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals following cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Cancer Institute grants K07 CA190529, R25CA102618-05, and UG1 CA189961, and by a research seed grant from the James P. Wilmot Cancer Institute.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine: The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlader N, Ries LA, Mariotto AB, et al. : Improved estimates of cancer-specific survival rates from population-based data. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:1584–1598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frisch M: On the etiology of anal squamous carcinoma. Dan Med Bull 2002;49:194–209 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grulich AE, van Leeuwen MT, Falster MO, Vajdic CM: Incidence of cancers in people with HIV/AIDS compared with immunosuppressed transplant recipients: A meta-analysis. Lancet 2007;370:59–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sell RL, Becker JB: Sexual orientation data collection and progress toward Healthy People 2010. Am J Public Health 2001;91:876–882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boehmer U, Glickman M, Winter M: Anxiety and depression in breast cancer survivors of different sexual orientations. J Consult Clin Psychol 2012;80:382–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boehmer U, Miao X, Ozonoff A: Cancer survivorship and sexual orientation. Cancer 2011;117:3796–3804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanton AL: Psychosocial concerns and interventions for cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:5132–5137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mao JJ, Armstrong K, Bowman MA, et al. : Symptom burden among cancer survivors: Impact of age and comorbidity. J Am Board Fam Med 2007;20:434–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holland JC, Bultz BD, National comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN): The NCCN guideline for distress management: A case for making distress the sixth vital sign. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2007;5:3–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deimling GT, Bowman KF, Sterns S, et al. : Cancer-related health worries and psychological distress among older adult, long-term cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2006;15:306–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamer M, Chida Y, Molloy GJ: Psychological distress and cancer mortality. J Psychosom Res 2009;66:255–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamen C, Palesh O, Gerry A, et al. : Disparities in health risk behavior and psychological distress among gay versus heterosexual male cancer survivors. LGBT Health 2014;1:86–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meulman JJ, Van Der Kooij AJ, Heiser WJ: Principal components analysis with nonlinear optimal scaling transformations for ordinal and nominal data. In: The Sage Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences. Kaplan D, ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. pp 49–70 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer IH: Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 2003;129:674–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartman ME, Irvine J, Currie KL, et al. : Exploring gay couples' experience with sexual dysfunction after radical prostatectomy: A qualitative study. J Sex Marital Ther 2014;40:233–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas C, Wootten A, Robinson P: The experiences of gay and bisexual men diagnosed with prostate cancer: Results from an online focus group. Eur J Cancer Care 2013;22:522–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boehmer U, Glickman M, Winter M, Clark MA: Lesbian and bisexual women's adjustment after a breast cancer diagnosis. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc 2013;19:280–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boehmer U, Glickman M, Milton J, Winter M: Health-related quality of life in breast cancer survivors of different sexual orientations. Qual Life Res 2012;21:225–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boehmer U: Twenty years of public health research: Inclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations. Am J Public Health 2002;92:1125–1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denney JT, Gorman BK, Barrera CB: Families, resources, and adult health: Where do sexual minorities fit? J Health Soc Behav 2013;54:46–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mustian KM, Sprod LK, Palesh OG, et al. : Exercise for the management of side effects and quality of life among cancer survivors. Curr Sports Med Rep 2009;8:325–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mock V, Frangakis C, Davidson N, et al. : Exercise manages fatigue during breast cancer treatment: A randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology 2005;14:464–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Payne JK, Held J, Thorpe J, et al. : Effect of exercise on biomarkers, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and depressive symptoms in older women with breast cancer receiving hormonal therapy. Oncol Nurs Forum 2008;35:635–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sprod LK, Palesh OG, Janelsins MC, et al. : Exercise, sleep quality, and mediators of sleep in breast and prostate cancer patients receiving radiation therapy. Community Oncol 2010;7:463–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Mackey JR, et al. : Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:4396–4404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mutrie N, Campbell AM, Whyte F, et al. : Benefits of supervised group exercise programme for women being treated for early stage breast cancer: Pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2007;334:517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strohle A: Physical activity, exercise, depression and anxiety disorders. J Neural Transm 2009;116:777–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM, Sela RA, et al. : The group psychotherapy and home-based physical exercise (group-hope) trial in cancer survivors: Physical fitness and quality of life outcomes. Psychooncology 2003;12:357–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamen C, Burns M, Beach SR: Minority stress in same-sex male relationships: When does it impact relationship satisfaction? J Homosex 2011;58:1372–1390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burns MN, Kamen C, Lehman KA, Beach SR: Attributions for discriminatory events and satisfaction with social support in gay men. Arch Sex Behav 2012;41:659–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Margolies L: The psychosocial needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2014;18:462–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Badger T, Segrin C, Dorros SM, et al. : Depression and anxiety in women with breast cancer and their partners. Nurs Res 2007;56:44–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mock V, Pickett M, Ropka ME, et al. : Fatigue and quality of life outcomes of exercise during cancer treatment. Cancer Pract 2001;9:119–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Northouse LL, Mood DW, Schafenacker A, et al. : Randomized clinical trial of a family intervention for prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer 2007;110:2809–2818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Badr H, Yeung C, Lewis MA, et al. : An observational study of social control, mood, and self-efficacy in couples during treatment for head and neck cancer. Psychol Health 2015;30:783–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewis MA, Butterfield RM: Antecedents and reactions to health-related social control. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2005;31:416–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewis MA, Rook KS: Social control in personal relationships: Impact on health behaviors and psychological distress. Health Psychol 1999;18:63–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mustian K, Peppone L, Sprod L, et al. : EXCAP exercise to improve fatigue, cardiopulmonary function, and strength: A phase II RCT among older prostate cancer patients receiving radiation and androgen deprivation therapy [abstract]. J Clin Oncol 2012;30(No 15_suppl):9010 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Markman HJ: Application of a behavioral model of marriage in predicting relationship satisfaction of couples planning marriage. J Consult Clin Psychol 1979;47:743–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanley SM, Ragan EP, Rhoades GK, Markman HJ: Examining changes in relationship adjustment and life satisfaction in marriage. J Fam Psychol 2012;26:165–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Christensen A, Atkins DC, Baucom B, Yi J: Marital status and satisfaction five years following a randomized clinical trial comparing traditional versus integrative behavioral couple therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol 2010;78:225–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Radloff LS: The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psych Measurement 1977;1:385–401 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hann D, Winter K, Jacobsen P: Measurement of depressive symptoms in cancer patients: Evaluation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). J Psychosom Res 1999;46:437–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spielberger C, Gorsuch R, Lushene R: The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1968 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spielberger CD, Sydeman SJ, Owen AE, Marsh BJ: Measuring anxiety and anger with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI). In: The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (2nd ed). Maruish ME, ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 1999. pp 993–1021 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vinokur AD, Vanryn M: Social support and undermining in close relationships - Their Independent effects on the mental-health of unemployed persons. J Pers Social Psych 1993;65:350–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ninness C, Newton R, Saxon J, et al. : Small group statistics: A Monte Carlo comparison of parametric and randomization tests. Behav Soc Iss 2002;12:53–63 [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Winter J: Using the Student's t-test with extremely small sample sizes. Pract Assess Res Eval 2013;18:1–12 [Google Scholar]