Abstract

Sleep disorders, including insomnia and excessive sleepiness, affect a significant proportion of patients with cancer and survivors, often in combination with fatigue, anxiety, and depression. Improvements in sleep lead to improvements in fatigue, mood, and quality of life. This section of the NCCN Guidelines for Survivorship provides screening, diagnosis, and management recommendations for sleep disorders in survivors. Management includes combinations of sleep hygiene education, physical activity, psychosocial interventions, and pharmacologic treatments.

Sleep disturbances include insomnia (trouble falling or staying asleep resulting in daytime dysfunction), excessive sleepiness (which can result from insufficient sleep opportunity, insomnia, or other sleep disorders), sleep-related movement or breathing disorders, and parasomnias.1 Sleep disorders affect 30% to 50% of patients with cancer and survivors, often in combination with fatigue, anxiety, or depression.1–10 Improvements in sleep lead to improvements in fatigue, mood, and quality of life.11 Most clinicians, however, do not know how best to evaluate and treat sleep disorders.1

Sleep disorders are common in patients with cancer as a result of multiple factors, including biologic changes, the stress of diagnosis and treatment, and side effects of therapy (eg, pain, fatigue).12 In addition, evidence suggests that changes in inflammatory processes from cancer and its treatment play a role in sleep disorders. These sleep disturbances can be perpetuated in the survivorship phase by chronic side effects, anxiety, depression, medications, and maladaptive behaviors such as shifting sleep times, excessive time in bed because of fatigue, and unplanned naps.12

Additional information about sleep disorders in patients with cancer can be found in the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) for Palliative Care and the NCCN Guidelines for Cancer-Related Fatigue (available at NCCN.org). These guidelines may be modified to fit the individual survivor’s circumstances.

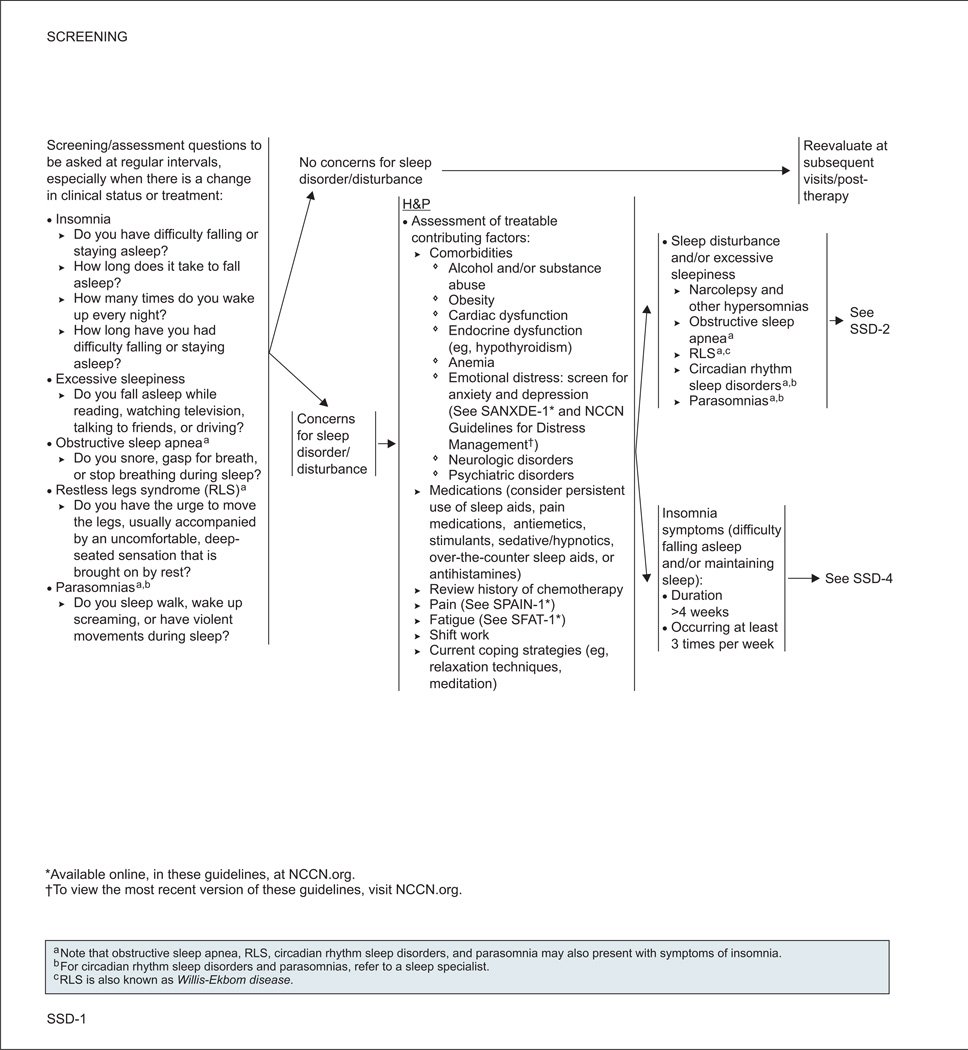

Screening for and Assessment of Sleep Disorders

Survivors should be screened for possible sleep disorders at regular intervals, especially when they experience a change in clinical status or treatment. The panel lists screening questions that can help determine whether concerns about sleep disorders or disturbances warrant further assessment. Other tools to screen for sleep problems have been validated.13,14

If concerns regarding sleep are significant, the panel recommends that treatable contributing factors be assessed and managed. Comorbidities that can contribute to sleep problems include alcohol and substance abuse, obesity, cardiac dysfunction, endocrine dysfunction, anemia, neurologic disorders, pain, fatigue, and emotional distress. In addition, some medications, both prescription and over-the-counter, can contribute to sleep issues. For instance, pain medication, antiemetics, and antihistamines can all contribute to sleep disturbance, as can the persistent use of sleep aids.

Diagnosis of Sleep Disorders

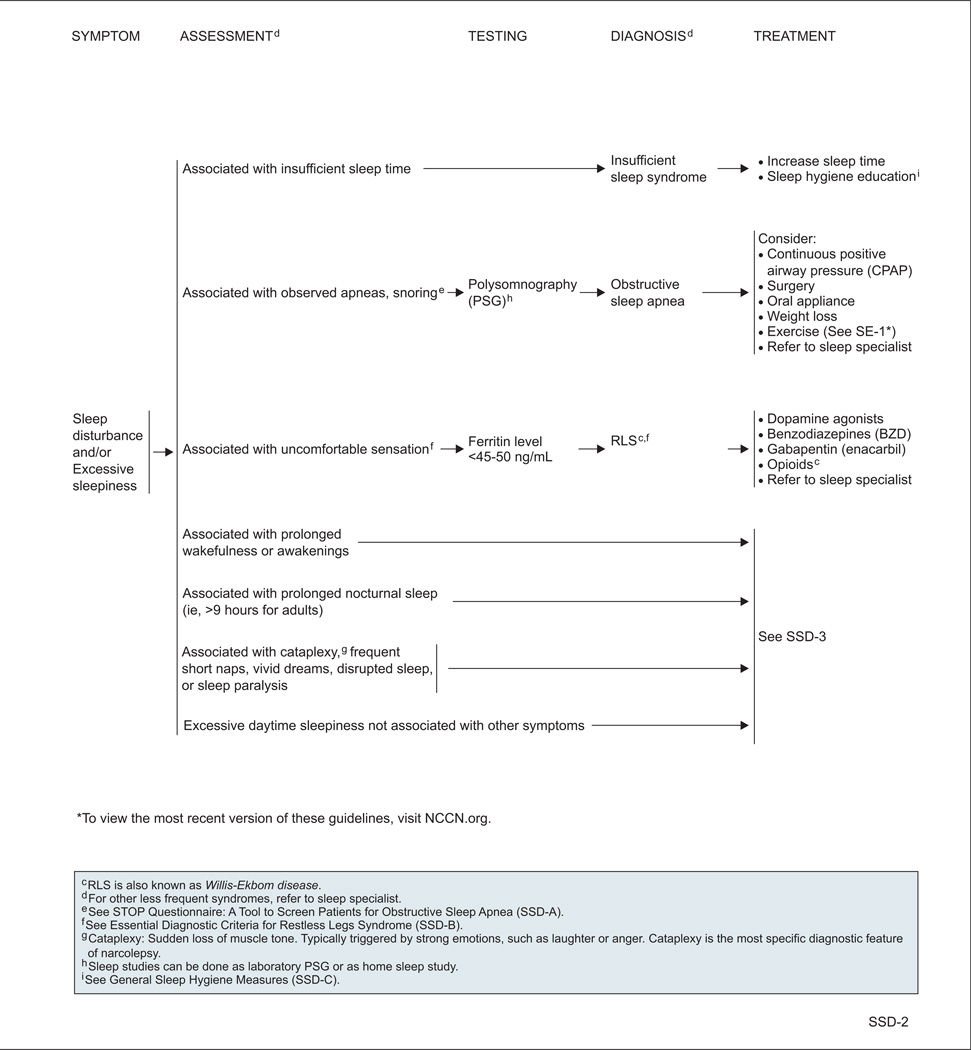

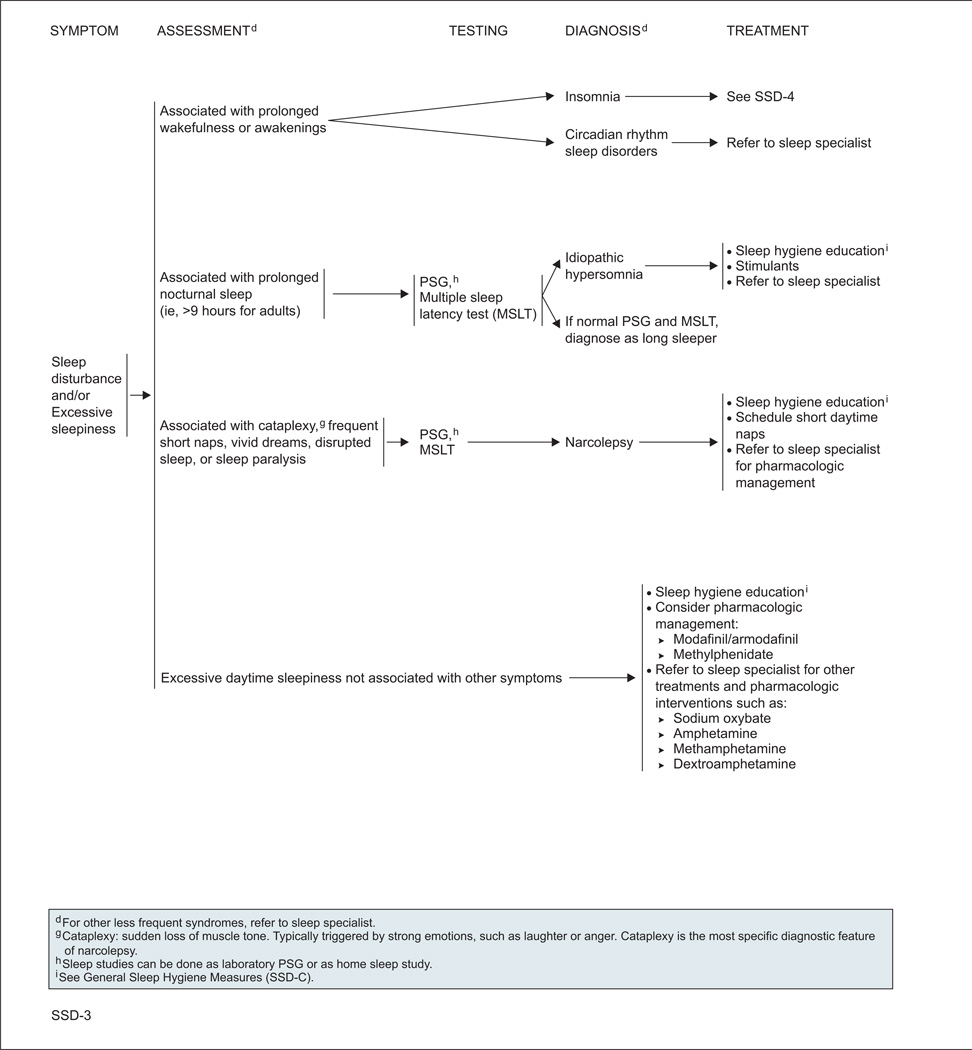

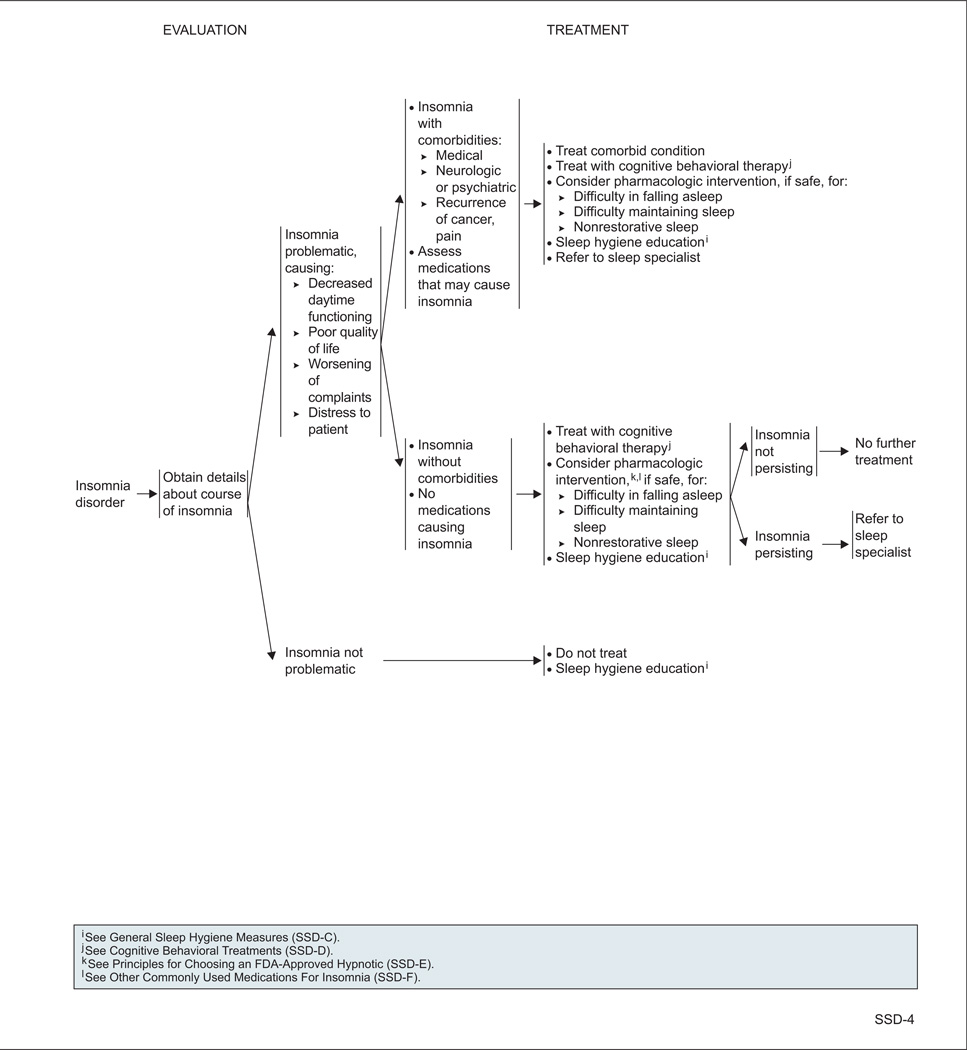

The panel divided sleep disorders into 2 general categories: insomnia, and sleep disturbance and/or excessive sleepiness.

Insomnia is diagnosed when patients have difficulty falling asleep and/or maintaining sleep at least 3 times per week for at least 4 weeks, accompanied by distress.

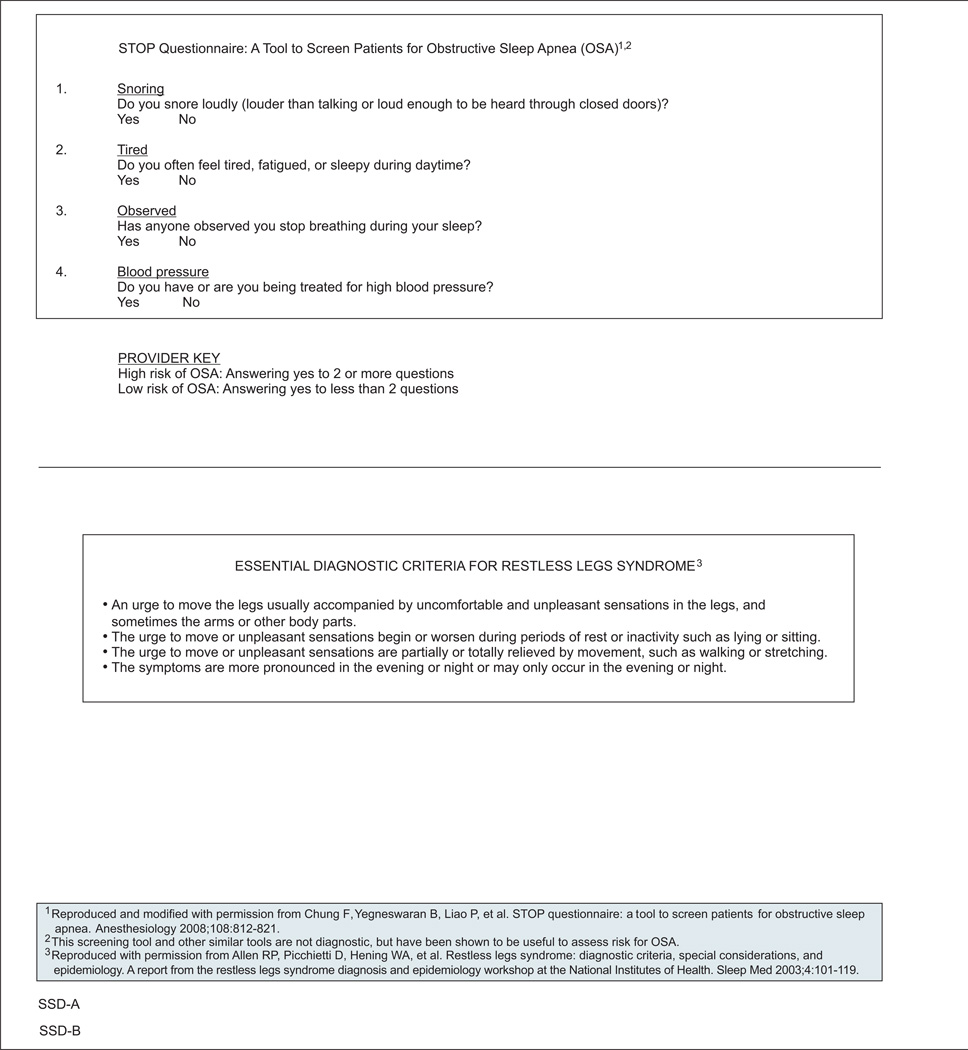

Diagnosing patients with excessive sleepiness can be challenging, because it can be caused by a variety of factors. When excessive sleepiness is associated with observed apneas or snoring, the STOP questionnaire can be used as a screening tool to determine the risk of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).15 Other screening tools for OSA risk have also been validated.16 Sleep studies (ie, laboratory polysomnography [PSG] or home sleep studies) can confirm the diagnosis of OSA. Multiple sleep latency tests (MSLTs) and PSG can also be useful in diagnosing narcolepsy, idiopathic hypersomnia, and parasomnias. Narcolepsy should be considered when excessive sleepiness is accompanied by cataplexy, frequent short naps, vivid dreams, disrupted sleep, or sleep paralysis.

Excessive sleepiness can also be associated with uncomfortable sensations or an urge to move the legs (and sometimes the arms or other body parts). These symptoms are usually worse at night and with inactivity, may be improved or relieved with movement such as walking or stretching, and indicate restless legs syndrome (RLS; also known as Willis-Ekbom disease). In these patients, ferritin levels should be checked; levels less than 45 to 50 ng/mL indicate a treatable cause of RLS.17,18

Management of Sleep Disorders

OSA should be treated with continuous positive airway pressure, surgery, or oral appliances.19–21 Additionally, weight loss and exercise should be recommended, and patients should be referred to a sleep specialist.

RLS is treated with dopamine agonists, benzodiazepines, gabapentin, and/or opioids, and referral to a sleep specialist.22–30 Two separate recent meta-analyses found dopamine agonists and calcium channel alpha-2-delta ligands (eg, gabapentin) to be helpful in reducing RLS symptoms and improving sleep in the noncancer setting.30,31

For other types of sleep disturbances, several types of interventions are recommended.1,32,33 In addition, referral to a sleep specialist can be considered in most cases.

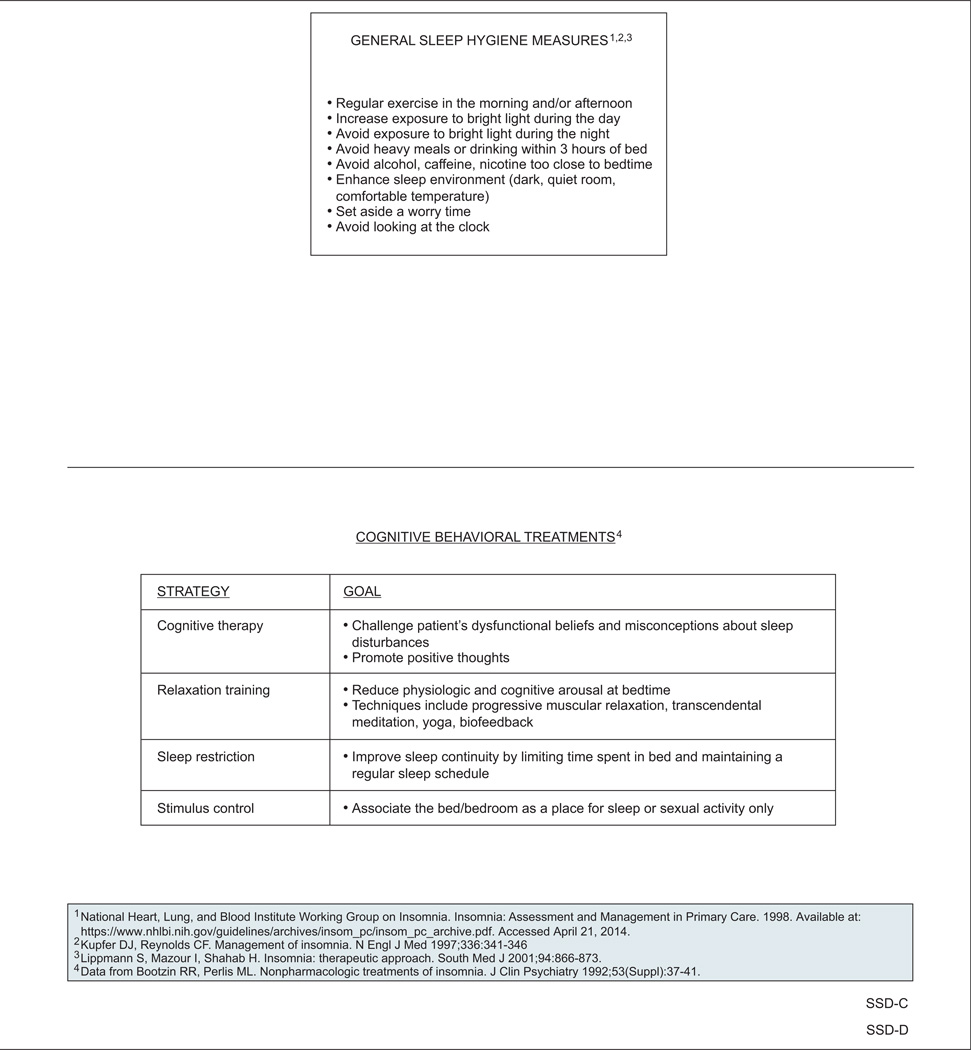

Sleep Hygiene Education

Educating survivors about general sleep hygiene is recommended, especially for the treatment of insomnia.34–36 Key points are listed in the guidelines and include regular morning or afternoon exercise; daytime exposure to bright light; keeping the sleep environment dark, quiet, and comfortable; and avoiding heavy meals, alcohol, and nicotine near bedtime.

Physical Activity

Physical activity may improve sleep in patients with cancer and survivors.37–43 One recent randomized controlled trial compared a standardized yoga intervention plus standard care with standard care alone in 410 survivors (75% breast cancer; 96% women) with moderate to severe sleep disruption.40 Participants in the yoga arm experienced greater improvements in global and subjective sleep quality, daytime functioning, and sleep efficiency (all P≤.05). In addition, the use of sleep medication declined in the intervention arm (P≤.05).

A recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in patients who had completed active cancer treatment showed that exercise improved sleep at a 12-week follow-up.38 Overall, however, data supporting improvement in sleep with physical activity are limited in the survivorship population.

Psychosocial Interventions

Psychosocial interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), psychoeducational therapy, and supportive expressive therapy are recommended to treat sleep disturbances in cancer survivors.44 In particular, several randomized controlled trials have shown that CBT improves sleep in the survivor population.45–48 For example, a randomized controlled trial in 150 survivors (58% breast cancer; 23% prostate cancer; 16% bowel cancer; 69% women) found that a series of 5 weekly group CBT sessions was associated with a reduction in mean wakefulness of almost 1 hour per night, whereas usual care (in which physicians could treat insomnia as they would in normal clinical practice) had no effect on wakefulness.45

In addition, a small randomized controlled trial of 57 survivors (54% breast cancer; 75% women) found that mind–body interventions (mindfulness meditation or mind–body bridging), decreased sleep disturbance more than sleep hygiene education did.49

Pharmacologic Interventions

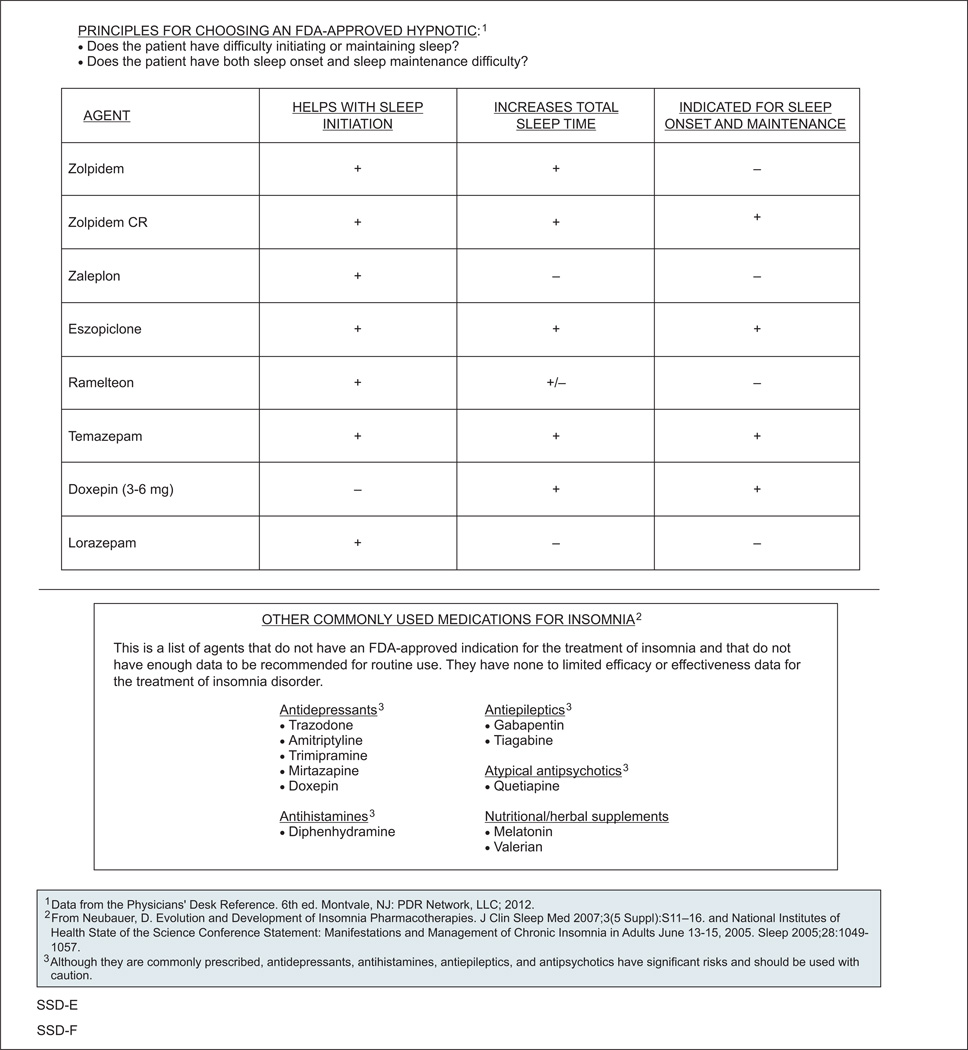

Many pharmacologic treatments for sleep disturbances are available, including psychostimulants for narcolepsy (eg, modafinil, methylphenidate) and hypnotics for insomnia (eg, zolpidem, ramelteon).33,50,51 In addition, antidepressants, antihistamines, antiepileptics, and antipsychotics are often used off-label for the treatment of insomnia, even though limited to no efficacy or effectiveness data are available for this use. The panel also noted that these medications are associated with significant risks and should be used with caution. One small, open-label study found that the antidepressant mirtazapine increased the total amount of nighttime sleep in patients with cancer.52 Overall, however, data on pharmacologic interventions aimed at improving sleep in patients with cancer and survivors are lacking.10

NCCN Categories of Evidence and Consensus.

Category 1: Based upon high-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 2A: Based upon lower-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 2B: Based upon lower-level evidence, there is NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 3: Based upon any level of evidence, there is major NCCN disagreement that the intervention is appropriate.

All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise noted.

Clinical trials: NCCN believes that the best management for any cancer patient is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) are a statement of consensus of the authors regarding their views of currently accepted approaches to treatment. Any clinician seeking to apply or consult the NCCN Guidelines® is expected to use independent medical judgment in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine any patient’s care or treatment. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) makes no representation or warranties of any kind regarding their content, use, or application and disclaims any responsibility for their applications or use in any way. The full NCCN Guidelines for Survivorship are not printed in this issue of JNCCN but can be accessed online at NCCN.org.

© National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2014, All rights reserved. The NCCN Guidelines and the illustrations herein may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

NCCN Sleep Disorders Panel Members

*,a,cCrystal S. Denlinger, MD/Chair†, Fox Chase Cancer Center

*,c,dJennifer A. Ligibel, MD/Vice Chair†, Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center

fMadhuri Are, MD£, Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer Center at The Nebraska Medical Center

b,eK. Scott Baker, MD, MS€ξ, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance

cWendy Demark-Wahnefried, PhD, RD≅, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Comprehensive Cancer Center

b,dDebra L. Friedman, MD, MS€‡, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center

*,gMindy Goldman, MDΩ, UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center

c,dLee Jones, PhDΠ, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

bAllison King, MD€Ψ‡, Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine

Grace H. Ku, MDξ‡, UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center

b,hElizabeth Kvale, MD£, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Comprehensive Cancer Center

aTerry S. Langbaum, MAS¥, The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins

gKristin Leonardi-Warren, RN, ND#, University of Colorado Cancer Center

bMary S. McCabe, RN, BS, MS#, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

b,c,d,gMichelle Melisko, MD†, UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center

eJose G. Montoya, MDΦ, Stanford Cancer Institute

a,dKathi Mooney, RN, PhD#, Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah

c,eMary Ann Morgan, PhD, FNP-BC#, Moffitt Cancer Center

Javid J. Moslehi, MDλÞ, Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center

d,hTracey O’Connor, MD†, Roswell Park Cancer Institute

cLinda Overholser, MD, MPHÞ, University of Colorado Cancer Center

cElectra D. Paskett, PhDε, The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center - James Cancer Hospital and Solove Research Institute

f,hMuhammad Raza, MD‡, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital/The University of Tennessee Health Science Center

fKaren L. Syrjala, PhDθ, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance

*,fSusan G. Urba, MD†£, University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center

gMark T. Wakabayashi, MD, MPHΩ, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center

*,hPhyllis Zee, MDΨΠ, Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University

NCCN Staff: Nicole McMillian, MS, and Deborah Freedman-Cass, PhD

KEY:

*Writing Committee Member

Subcommittees: aAnxiety and Depression; bCognitive Function; cExercise; dFatigue; eImmunizations and Infections; fPain; gSexual Function; hSleep Disorders

Specialties: ξBone Marrow Transplantation; λCardiology; εEpidemiology; ΠExercise/Physiology; ΩGynecology/Gynecologic Oncology; ‡Hematology/Hematology Oncology; ΦInfectious Diseases; ÞInternal Medicine; †Medical Oncology; ΨNeurology/Neuro-Oncology; #Nursing; ; ≅Nutrition Science/Dietician; ¥Patient Advocacy; €Pediatric Oncology; θPsychiatry, Psychology, Including Health Behavior; £Supportive Care Including Palliative, Pain Management, Pastoral Care, and Oncology Social Work; ¶Surgery/Surgical Oncology; ωUrology

Footnotes

Disclosures for the NCCN Survivorship Panel

At the beginning of each NCCN Guidelines panel meeting, panel members review all potential conflicts of interest. NCCN, in keeping with its commitment to public transparency, publishes these disclosures for panel members, staff, and NCCN itself.

Individual disclosures for the NCCN Survivorship Panel members can be found on page 642. (The most recent version of these guidelines and accompanying disclosures are available on the NCCN Web site at NCCN.org.)

These guidelines are also available on the Internet. For the latest update, visit NCCN.org.

| Panel Member | Clinical Research Support/Data Safety Monitoring Board |

Advisory Boards, Speakers Bureau, Expert Witness, or Consultant |

Patent, Equity, or Royalty |

Other | Date Completed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madhuri Are, MD | None | None | None | None | 5/15/13 |

| K. Scott Baker, MD, MS | None | None | None | None | 11/22/13 |

| Wendy Demark-Wahnefried, PhD, RD | National Cancer Institute; Harvest for Health Gardening Project for Breast Cancer Survivors; and Nutrigenomic Link between Alpha- Linolenic Acid and Aggressive Prostate Cancer | American Society of Clinical Oncology | None | American Society of Preventive Oncology | 11/13/13 |

| Crystal S. Denlinger, MD | Bayer HealthCare; ImClone Systems Incorporated; MedImmune Inc.; OncoMed Pharmaceuticals; Astex Pharmaceuticals; Merrimack Pharmaceuticals; and Pfizer Inc. | Eli Lilly and Company | None | None | 1/9/14 |

| Debra L. Friedman, MD, MS | None | None | None | None | 5/26/13 |

| Mindy Goldman, MD | Pending | ||||

| Lee W. Jones, PhD | None | None | None | None | 2/2/12 |

| Allison King, MD | None | None | None | None | 8/12/13 |

| Grace H. Ku, MD | None | None | None | None | 8/13/13 |

| Elizabeth Kvale, MD | None | None | None | None | 10/7/13 |

| Terry S. Langbaum, MAS | None | None | None | None | 8/13/13 |

| Kristin Leonardi-Warren, RN, ND | None | None | None | None | 1/6/14 |

| Jennifer A. Ligibel, MD | None | None | None | None | 10/3/13 |

| Mary S. McCabe, RN, BS, MS | None | None | None | None | 8/12/13 |

| Michelle Melisko, MD | Celldex Therapeutics; and Galena Biopharma | Agendia BV; Genentech, Inc.; and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation | None | None | 10/11/13 |

| Jose G. Montoya, MD | None | None | None | None | 12/6/13 |

| Kathi Mooney, RN, PhD | University of Utah | None | None | None | 9/30/13 |

| Mary Ann Morgan, PhD, FNP-BC | None | None | None | None | 8/19/13 |

| Javid J. Moslehi, MD | None | ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; and Pfizer Inc. | None | None | 1/27/14 |

| Tracey O’Connor, MD | None | None | None | None | 6/13/13 |

| Linda Overholser, MD, MPH | None | Antigenics Inc.; and Colorado Central Cancer Registry Care Plan Project | None | None | 10/10/13 |

| Electra D. Paskett, PhD | Merck & Co., Inc. | None | None | None | 6/13/13 |

| Muhammad Raza, MD | None | None | None | None | 8/23/12 |

| Karen L. Syrjala, PhD | None | None | None | None | 10/3/13 |

| Susan G. Urba, MD | None | Eisai Inc.; and Helsinn Therapeutics (U.S.), Inc. | None | None | 10/9/13 |

| Mark T. Wakabayashi, MD, MPH | None | None | None | None | 6/19/13 |

| Phyllis Zee, MD | Philips/Respironics | Merck & Co., Inc.; Jazz Pharmaceuticals; Vanda Pharmaceuticals; and Purdue Pharma LP | None | None | 3/26/14 |

References

- 1.Berger AM, Mitchell SA. Modifying cancer-related fatigue by optimizing sleep quality. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2008;6:3–13. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2008.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ancoli-Israel S, Moore PJ, Jones V. The relationship between fatigue and sleep in cancer patients: a review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2001;10:245–255. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2001.00263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ancoli-Israel S. Recognition and treatment of sleep disturbances in cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5864–5866. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.5993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carney S, Koetters T, Cho M, et al. Differences in sleep disturbance parameters between oncology outpatients and their family caregivers. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1001–1006. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.9104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiorentino L, Ancoli-Israel S. Insomnia and its treatment in women with breast cancer. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:419–429. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiorentino L, Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep dysfunction in patients with cancer. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2007;9:337–346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flynn KE, Shelby RA, Mitchell SA, et al. Sleep-wake functioning along the cancer continuum: focus group results from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) Psychooncology. 2010;19:1086–1093. doi: 10.1002/pon.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forsythe LP, Helzlsouer KJ, MacDonald R, Gallicchio L. Daytime sleepiness and sleep duration in long-term cancer survivors and non-cancer controls: results from a registry-based survey study. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:2425–2432. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1358-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu L, Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep disturbances in cancer. Psychiatr Ann. 2008;38:627–634. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20080901-01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zee PC, Ancoli-Israel S. Does effective management of sleep disorders reduce cancer-related fatigue? Drugs. 2009;69(Suppl 2):29–41. doi: 10.2165/11531140-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dirksen SR, Epstein DR. Efficacy of an insomnia intervention on fatigue, mood and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. J Adv Nurs. 2008;61:664–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palesh O, Aldridge-Gerry A, Ulusakarya A, et al. Sleep disruption in breast cancer patients and survivors. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:1523–1530. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Omachi TA. Measures of sleep in rheumatologic diseases: Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), Functional Outcome of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ), Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(Suppl 11):S287–S296. doi: 10.1002/acr.20544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savard MH, Savard J, Simard S, Ivers H. Empirical validation of the Insomnia Severity Index in cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2005;14:429–441. doi: 10.1002/pon.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:812–821. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31816d83e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silva GE, Vana KD, Goodwin JL, et al. Identification of patients with sleep disordered breathing: comparing the four-variable screening tool, STOP, STOP-Bang, and Epworth Sleepiness Scales. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7:467–472. doi: 10.5664/JCSM.1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchfuhrer MJ. Strategies for the treatment of restless legs syndrome. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9:776–790. doi: 10.1007/s13311-012-0139-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moyer DE, Zayas-Bazan J, Reese G. Restless legs syndrome: diagnostic time-savers, Tx tips. J Fam Pract. 2009;58:415–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antonescu-Turcu A, Parthasarathy S. CPAP and bi-level PAP therapy: new and established roles. Respir Care. 2010;55:1216–1229. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ballard RD. Management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Fam Pract. 2008;57:S24–S30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weingarten JA, Basner RC. Advances in the management of adult obstructive sleep apnea. F1000 Med Rep. 2009;1 doi: 10.3410/M1-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bassetti CL, Bornatico F, Fuhr P, et al. Pramipexole versus dual release levodopa in restless legs syndrome: a double blind, randomised, cross-over trial. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141:w13274. doi: 10.4414/smw.2011.13274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferini-Strambi L, Aarskog D, Partinen M, et al. Effect of pramipexole on RLS symptoms and sleep: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Sleep Med. 2008;9:874–881. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan PW, Allen RP, Buchholz DW, Walters JK. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the treatment of periodic limb movements in sleep using carbidopa/levodopa and propoxyphene. Sleep. 1993;16:717–723. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.8.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manconi M, Ferri R, Zucconi M, et al. Pramipexole versus ropinirole: polysomnographic acute effects in restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 2011;26:892–895. doi: 10.1002/mds.23543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montplaisir J, Nicolas A, Denesle R, Gomez-Mancilla B. Restless legs syndrome improved by pramipexole: a double-blind randomized trial. Neurology. 1999;52:938–943. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.5.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oertel WH, Stiasny-Kolster K, Bergtholdt B, et al. Efficacy of pramipexole in restless legs syndrome: a six-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind study (effect-RLS study) Mov Disord. 2007;22:213–219. doi: 10.1002/mds.21261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trenkwalder C, Garcia-Borreguero D, Montagna P, et al. Ropinirole in the treatment of restless legs syndrome: results from the TREAT RLS 1 study, a 12 week, randomised, placebo controlled study in 10 European countries. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:92–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walters AS, Ondo WG, Dreykluft T, et al. Ropinirole is effective in the treatment of restless legs syndrome. TREAT RLS 2: a 12-week, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study. Mov Disord. 2004;19:1414–1423. doi: 10.1002/mds.20257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilt TJ, MacDonald R, Ouellette J, et al. Pharmacologic therapy for primary restless legs syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:496–505. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hornyak M, Scholz H, Kohnen R, et al. What treatment works best for restless legs syndrome? Meta-analyses of dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic medications. Sleep Med Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgenthaler T, Kramer M, Alessi C, et al. Practice parameters for the psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: an update. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep. 2006;29:1415–1419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morgenthaler TI, Kapur VK, Brown T, et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of narcolepsy and other hypersomnias of central origin. Sleep. 2007;30:1705–1711. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.12.1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Insomnia: assessment and management in primary care. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Working Group on Insomnia. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:3029–3038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kupfer DJ, Reynolds CF., 3rd Management of insomnia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:341–346. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701303360506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lippmann S, Mazour I, Shahab H. Insomnia: therapeutic approach. South Med J. 2001;94:866–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheville AL, Kollasch J, Vandenberg J, et al. A home-based exercise program to improve function, fatigue, and sleep quality in patients with stage IV lung and colorectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:811–821. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mishra SI, Scherer RW, Geigle PM, et al. Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD007566. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007566.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mishra SI, Scherer RW, Snyder C, et al. Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for people with cancer during active treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD008465. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008465.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mustian KM, Sprod LK, Janelsins M, et al. Multicenter, randomized controlled trial of yoga for sleep quality among cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3233–3241. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.7707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Payne JK, Held J, Thorpe J, Shaw H. Effect of exercise on biomarkers, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and depressive symptoms in older women with breast cancer receiving hormonal therapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:635–642. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.635-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rogers LQ, Fogleman A, Trammell R, et al. Effects of a physical activity behavior change intervention on inflammation and related health outcomes in breast cancer survivors: pilot randomized trial. Integr Cancer Ther. 2013;12:323–335. doi: 10.1177/1534735412449687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Gerpen RE, Becker BJ. Development of an evidence-based exercise and education cancer recovery program. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:539–543. doi: 10.1188/13.CJON.539-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bootzin RR, Perlis ML. Nonpharmacologic treatments of insomnia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1992;53(Suppl):37–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Espie CA, Fleming L, Cassidy J, et al. Randomized controlled clinical effectiveness trial of cognitive behavior therapy compared with treatment as usual for persistent insomnia in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4651–4658. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Epstein DR, Dirksen SR. Randomized trial of a cognitive-behavioral intervention for insomnia in breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:E51–E59. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.E51-E59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gielissen MF, Verhagen S, Witjes F, Bleijenberg G. Effects of cognitive behavior therapy in severely fatigued disease-free cancer patients compared with patients waiting for cognitive behavior therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4882–4887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Savard J, Simard S, Ivers H, Morin CM. Randomized study on the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia secondary to breast cancer, part I: sleep and psychological effects. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6083–6096. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakamura Y, Lipschitz DL, Kuhn R, et al. Investigating efficacy of two brief mind-body intervention programs for managing sleep disturbance in cancer survivors: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:165–182. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0252-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health State of the Science Conference statement on Manifestations and Management of Chronic Insomnia in Adults, June 13–15, 2005. Sleep. 2005;28:1049–1057. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.9.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neubauer DN. The evolution and development of insomnia pharmacotherapies. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:S11–S15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim SW, Shin IS, Kim JM, et al. Effectiveness of mirtazapine for nausea and insomnia in cancer patients with depression. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;62:75–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]