Abstract

Importance

Exposure to nicotine in electronic (e-) cigarettes is common among adolescents who report never having smoked combustible tobacco.

Objectives

To evaluate whether e-cigarette ever-use among 14-year-olds who have never tried combustible tobacco is associated with risk of initiating use of three combustible tobacco products (i.e., cigarettes, cigars, and hookah).

Design

Longitudinal repeated assessment of a school-based cohort at baseline (fall 2013, 9th grade, Mean age=14.1) and 6-month (spring 2014, 9th grade) and 12-month (fall 2014, 10th grade) follow-ups.

Setting and Participants

Ten public high schools in Los Angeles, CA were recruited through convenience sampling. Participants were students who reported never using combustible tobacco at baseline and underwent follow-up assessment (N=2,530). At each time point, students completed self-report surveys during in-classroom data collections.

Exposure

Self-report of e-cigarette ever-use (yes/no) at baseline.

Main Outcome Measures

Six- and 12-month follow-up reports of use of each of the following tobacco products within the prior 6 months: (1) any combustible tobacco product (yes/no); (2) combustible cigarettes (yes/no), (3) cigars (yes/no); (4) hookah (yes/no); and (5) number of combustible tobacco products (range: 0–3).

Results

Past 6-month use of any combustible tobacco product was more frequent in baseline e-cigarette ever-users (N=222) than never-users (N=2,308) at the 6-month (30.7% vs. 8.1%, % difference [95% CI]=22.7[16.4, 28.9]) and 12-month (25.2% vs. 9.3%, % difference [95% CI]= 15.9[10.0, 21.8]) follow-ups. Baseline ever e-cigarette use was associated with greater likelihood of combustible tobacco use averaged across the two follow-ups in unadjusted analyses (OR[95% CI]=4.27[3.19, 5.71]) and in analyses adjusted for sociodemographic, environmental, and intrapersonal risk factors for smoking (OR[95% CI]=2.73[2.00, 3.73]). Product-specific analyses showed that baseline e-cigarette ever-use was positively associated with combustible cigarette (OR[95% CI]=2.65[1.73, 4.05]), cigar (OR[95% CI]=4.85[3.38, 6.96]), and hookah (OR[95% CI]=3.25[2.29, 4.62]) use and number of different combustible products used (OR[95% CI]=4.26[3.16, 5.74]) averaged across the two follow-ups.

Conclusion and Relevance

Among high school students in Los Angeles, those who used electronic cigarettes at baseline compared with nonusers were more likely to report initiation of combustible tobacco smoking over the next year. Further research is needed to understand whether this association may be causal.

Keywords: adolescents, electronic cigarettes, smoking, tobacco, risk factor

INTRODUCTION

Nicotine is addictive when delivered in tobacco smoke, which provides a significant dose of nicotine that travels quickly to the brain after inhalation.1 Combustible tobacco, which has well-known health consequences, has long been the dominant nicotine-delivering product used in the population. Electronic (e-) cigarettes—devices that deliver inhaled aerosol generally containing nicotine—are becoming increasingly popular, particularly among adolescents, including teens who have never used combustible tobacco.2,3 According to 2014 national estimates, 16% of 10th graders reported use of e-cigarettes in the past 30 days, of whom, 43% reported never having tried combustible cigarettes.3

Whether use of e-cigarettes is associated with risk of initiating combustible tobacco smoking is presently unknown. Enjoyment of the sensations and pharmacological effects of inhaling nicotine via e-cigarettes could increase propensity to try other products that similarly deliver inhaled nicotine, including combustible tobacco products. If e-cigarette use is a risk factor for combustible tobacco use initiation, the high prevalence of e-cigarette use in the adolescent population could ultimately perpetuate and potentially enlarge the epidemic of tobacco-related illness. Because the first year of high school is a vulnerable period for initiating risky behaviors,4 this study investigated whether adolescents entering 9th grade in the city of Los Angeles who reported ever using e-cigarettes were more likely to initiate the use of combustible tobacco over the subsequent year.

METHODS

Participants and Procedure

Data were collected as part of a longitudinal survey of substance use and mental health among high school students in Los Angeles, CA. Approximately 40 public high schools in the Los Angeles, CA metropolitan area were approached about participating in this study; these schools were chosen because of their diverse demographic characteristics and proximity. Ten schools agreed to participate in the study (see Table e1 for school characteristics). To enroll in the study, students and their parents were required to provide active written or verbal assent and consent, respectively. Data collection involved three assessment waves that took place approximately 6 months apart: baseline (fall 2013, 9th Grade), 6-month follow-up (spring 2014, 9th Grade), and 12-month follow-up (fall 2014, 10th Grade). At each wave, paper-and-pencil surveys were administered in students’ classrooms on-site. Students not in class during data collections completed phone or web surveys. The University of Southern California Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Measures

Each study measure described below has shown adequate psychometric properties in previous youth samples.5–9

Electronic Cigarette and Combustible Tobacco Product Use

At each wave, items based on the Youth Behavior Risk Surveillance (YRBS)5 and Monitoring the Future (MTF)6 Surveys assessed lifetime and past 6-month use (yes/no) of e-cigarettes, combustible cigarettes (described as “even a few puffs”), full-size cigars, little cigars/cigarillos, hookah water pipe, and blunts (“marijuana rolled in a tobacco leaf or cigar casing”). Response to the lifetime e-cigarette use question at baseline was the primary exposure variable. Outcomes were any use, in the prior 6 months, of: (1) any combustible tobacco product (yes/no); (2) combustible cigarettes (yes/no); (3) cigars (full-size cigars, little cigars, or blunts; yes/no); (4) hookah (yes/no); and (5) number of combustible tobacco products (cigarette, cigar, hookah; range: 0 – 3). A composite cigar variable was used because of infrequent use of individual cigar products. Blunt use was included given the high prevalence in this sample, association with adolescent e-cigarette use in past work,10 and evidence that there are significant tobacco smoke toxicants in blunt smoke.11 A sensitivity analysis was conducted which compared rates of non-blunt cigar use at 6- and 12-month follow-ups by baseline e-cigarette ever use. The terms “ever-smokers” and “never-smokers” are used to refer to adolescents who ever and never used any of the three combustible tobacco products, respectively.

Covariates

Variables peripheral to a putative pathway by which e-cigarette use may be directly associated with risk of combustible tobacco use initiation, yet potentially overlapping with both e-cigarette and combustible tobacco use, were selected a priori as covariates based on the previous literature.10,12–16 Covariates were selected from three domains.

Sociodemographics

Sociodemographic characteristics including age, gender, ethnicity/race, and highest parental education were assessed using self-report responses to investigator-defined forced choice items (see Table 1 for response categories).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Baseline Ever E-Cigarette Use Status Among Baseline Never-Smokers

| Outcome | Baseline E-Cigarette Use

|

Contrast by Ever E-Cigarette Use P value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N= 2,530) |

Never Use (N=2,308) |

Ever Use (N=222) |

||

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Gendera | – | – | – | <.001* |

| Female, n (%) | 1,343 (53.2%) | 1,252 (54.3%) | 91 (41.4%) | |

| Male, n (%) | 1,181 (46.8%) | 1,052 (45.7%) | 129 (58.6%) | |

| Age, M (95%CI)b | 14.06 (14.04, 14.07) | 14.05 (14.04, 14.07) | 14.10 (14.05, 14.15) | .11** |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%)c | – | – | – | .02* |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 21 (0.8%) | 19 (0.8%) | 2 (0.9%) | |

| Asian | 472 (19.0%) | 432 (19.0%) | 40 (18.7%) | |

| Black/African American | 119 (4.8%) | 107 (4.7%) | 12 (5.6%) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1,099 (44.2%) | 998 (43.9%) | 101 (47.2%) | |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 89 (3.6%) | 74 (3.3%) | 15 (7.0 %) | |

| White | 404 (16.2%) | 383 (16.9%) | 21 (9.8 %) | |

| Other | 142 (5.7%) | 134 (5.9%) | 8 (3.7 %) | |

| Multi-ethnic/Multi-Racial | 141 (5.7%) | 126 (5.5%) | 15 (7.0 %) | |

| Highest parental education, n (%)d | – | – | – | .03*** |

| 8th grade or less | 72 (3.3%) | 69 (3.4%) | 3 (1.6%) | |

| Some high school | 171 (7.8%) | 151 (7.5%) | 20 (10.4%) | |

| High school graduate | 334 (15.2%) | 298 (14.8%) | 36 (18.8%) | |

| Some college | 428 (19.5%) | 384 (19.1%) | 44 (22.9%) | |

| College graduate | 741 (33.7%) | 683 (34.01%) | 58 (30.2%) | |

| Graduate degree | 454 (20.6%) | 423 (21.1%) | 31 (16.2%) | |

| Environmental factors | ||||

| Lives with both biological parents, n (%)e | 1,688 (67.3%) | 1,563 (68.3%) | 125 (56.6%) | <.001* |

| Family history of smoking, n (%)f | 1,487 (61.2%) | 1,337 (60.3%) | 150 (70.8%) | .003* |

| Peer smoking, M (95%CI)g | 0.22 (0.19, 0.25) | 0.20 (0.17, 0.23) | 0.46 (0.32, 0.59) | <.001* |

| Intrapersonal factors | ||||

| CESD-Depressive Symptoms, M (95%CI)h | 13.49 (13.06, 13.93) | 13.37 (12.91, 13.82) | 14.80 (13.27, 16.33) | .07** |

| TCI-Impulsivity, M (95%CI)i | 2.39 (2.33, 2.45) | 2.35 (2.29, 2.41) | 2.76 (2.58, 2.94) | <.001** |

| Ever substance use, n % | 454 (17.9%) | 345 (15.0%) | 109 (49.1%) | <.001* |

| Delinquent Behavior, M (95%CI)j | 14.64 (14.50, 14.79) | 14.43 (14.29, 14.57) | 16.88 (16.12, 17.64) | <.001** |

| Smoking susceptibility, M (95%CI)k | 1.11 (1.10, 1.12) | 1.10 (1.09, 1.11) | 1.22 (1.16, 1.27) | <.001** |

| Smoking expectancies, M (95%CI)l | 1.39 (1.37, 1.41) | 1.38 (1.36, 1.40) | 1.48 (1.40, 1.55) | .02** |

Note. Due to missing data for each respective variable, denominators are

N=2,524,

N=2,519,

N=2,487,

N=2,200,

N=2,510,

N=2,430,

N=2,484,

N=2,490,

N=2,481,

N=2,496,

N=2,506,

N=2,502.

Chi-square test.

Independent samples t-test.

Spearmans ρ test. M= Mean. CI = Confidence Interval. CESD = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; TCI = Temperament and Character Inventory.

Environmental variables

Indicators of the proximal environment included family living situation, measured with the item, “Who do you live with most of the time?” (both biological parents vs. other).12 Family history of smoking was measured using the question, “Does anyone in your immediate family (brothers/sisters/parents/grandparents) have a history of smoking cigarettes?” (yes/no). Peer smoking was assessed by responses to the item, “In the last 30 days, how many of your five closest friends have smoked cigarettes?” (range: 0–5).17

Intrapersonal factors

Mental health, personality traits, and psychological processes linked with experimentation, risky behavior, and smoking were assessed. Depressive symptoms were measured using the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD)8 composite sum past week frequency rating (e.g., 0=Rarely or none of the time [0–1 days] to 3=Most or all of the time [5–7 days]). Impulsivity was measured with the 5-item Temperament and Character Inventory Impulsivity subscale sum score, which assesses tendency towards acting on instinct without conscious deliberation (e.g., “I often do things based on how I feel at the moment”; range: 0–5).18 Ever use of non-nicotine/tobacco substances was measured using MTF/YRBS items assessing ever use of alcohol and 13 separate illicit and prescription substances of abuse (use of ≥1 vs. 0 substances). Delinquent behavior was measured with a mean of frequency ratings for engaging in 11 different behaviors (e.g., stealing, lying to parents; 1=Never to 6=Ten or more times) in the past 6 months.19 Susceptibility to smoking was measured by a three-item index, averaging responses to “Would you try smoking a cigarette if one of your best friends offered it to you?,” “Do you think you would smoke in the next 6 months?,” and “Are you curious about smoking?” (1=Definitely Not, 2=Probably Not, 3=Probably Yes, 4=Definitely Yes).9 Smoking outcome expectancies were assessed using the average of the two responses for “I think I might enjoy…smoking” and (reversed) “I think I might feel bad…from smoking” (1=Strongly Disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Agree, 4=Strongly Agree).20

Data Analysis

The prevalence and association of e-cigarette and combustible tobacco use in the overall baseline sample of never- and ever-smokers are reported first. Then, in the sample of baseline never-smokers, correlates of study attrition and descriptive statistics are reported. Primary analyses used repeated measures generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs),21 an extension of logistic regression, in which each participant had two timepoints of follow-up data (6- and 12-month follow-up). Separate GLMMs were constructed for each binary outcome (i.e., any combustible tobacco product, cigarettes, cigars, hookah) and the ordinal number of combustible products (cumulative logit) outcome at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. All models included baseline e-cigarette ever-use, school, and time (6-month vs. 12-month follow-up) as fixed effects and were fit with and without adjustment for all covariates. The parameter estimate from each regressor/covariate reflected the association with the outcome averaged across the two follow-ups. To explore whether the association between baseline e-cigarette and combustible tobacco use differed across the follow-ups, the baseline e-cigarette × time interaction term was added to each model in a subsequent step. Participants with missing data on baseline e-cigarette use or the respective outcome variable were not included in GLMMs. Missing data on covariates were accounted for using a multiple imputation approach,22 which replaces each missing value with a set of plausible values that represent the uncertainty about the correct value to impute. Using the Markov chain Monte Carlo method for missing at random assumptions and the available covariate data, five multiply imputed data sets were created. The parameter estimates from models tested in each imputed dataset were pooled and presented as a single estimate. The amount of missing data for each covariate can be found in the Table 1 note. Continuous variables were rescaled (M=0, SD=1) for GLMMs to facilitate interpretation. Analyses were conducted in SAS Version 9.3.23 Significance was set to 0.05 and all tests were two-tailed. A Bonferroni-Holm correction24 for multiple tests was applied.

RESULTS

Study Sample

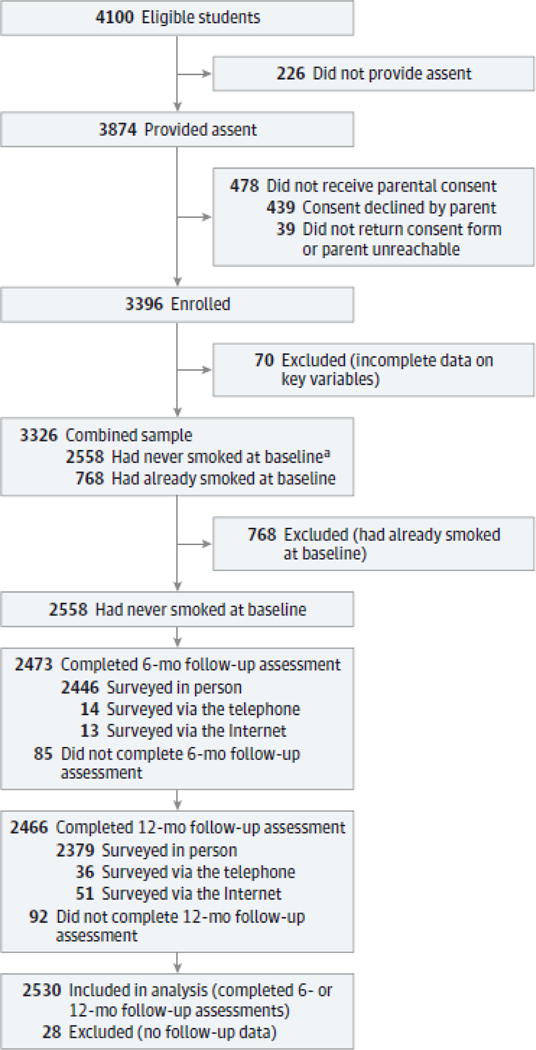

All ninth-grade English-speaking students not in special education (e.g., severe learning disabilities) were eligible to participate (N=4,100). Of the assenting students (N=3,874; 94.5%), 3,396 (87.7%) provided parental consent, from whom data was collected for 3,383 (99.6%), 3,293 (97.0%), and 3,282 (96.6%) participants, at baseline and 6- and 12-month follow-ups, respectively. The analytic samples available for analyses in this report across waves are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flow of Adolescent Students in Study to Assess e-Cigarette Use at Baseline and Later Use of Combustible Tobacco Products.

a Includes all 3 combustible tobacco products (ie, combustible cigarettes, cigars, hookah).

Descriptive Analyses

In the combined sample of ever- (N=768) and never-smokers (N=2,558), baseline e-cigarette ever use was positively associated with baseline ever use of each combustible tobacco product; prevalence ranged from 10.5% to 15.2% for the combustible tobacco products and the prevalence of ever-use of e-cigarettes was 18.6% (Table 2). Twelve percent of participants used e-cigarettes and some form of combustible tobacco, 11.7% used combustible tobacco only, 6.7% used e-cigarettes only, and 69.7% used neither product.

Table 2.

Prevalence and Cross-Sectional Association of Baseline E-Cigarette Use and Combustible Tobacco Use in Combined Sample of Baseline Ever-Smokers and Never-Smokers

| Baseline Ever Use | Baseline E-Cigarette | Baseline E-Cigarette | Difference in Prevalence Rates

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N=3,326) |

Never-Users (N=2,709) |

Ever-Users (N=617) |

% (95%CI) | P Value | |

| Any Combustible Tobacco Product, n (%) | 768 (23.1%) | 376 (13.9%) | 392 (63.5%) | 49.7 (45.6, 53.7) | <.001* |

| Combustible Cigarettes, n (%)a | 349 (10.5%) | 153 (5.7%) | 196 (32.0%) | 26.4 (22.6, 30.2) | <.001* |

| Cigars, n (%)b | 419 (12.6%) | 168 (6.2%) | 251 (40.8%) | 34.6 (30.6, 38.6) | <.001* |

| Hookah, n (%)c | 501 (15.2%) | 220 (8.2%) | 281 (46.5%) | 38.3 (34.2, 42.4) | <.001* |

| Number of Different Combustible Tobacco | – | – | – | – | <.001* |

| Products, n (%) | |||||

| 0 products | 2,558 (76.9%) | 2,333 (86.1%) | 225 (36.4%) | ||

| 1 product | 401 (12.1%) | 245 (9.0%) | 156 (25.3%) | ||

| 2 products | 233 (7.0%) | 97 (3.6%) | 136 (22.0%) | ||

| 3 products | 134 (4.0%) | 34 (1.3%) | 100 (16.2%) | ||

Note. Due to missing data for each respective variable, denominators are

N=3,320,

N=3,324,

N=3,304,

Chi-square test.

Baseline never-smokers with (N=2,530) versus without (N=28) follow-up data did not differ in baseline e-cigarette ever use or any sociodemographic characteristic besides age (P=.006; participants without data were older). There were positive associations of e-cigarette ever use with male gender, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander ethnicity, lower parental education and most environmental and intrapersonal covariates (see Table 1).

Associations between Baseline E-Cigarette Ever Use and Combustible Tobacco Use at Follow-Ups in Baseline Never-Smokers

In the sample of never-smokers, baseline e-cigarette ever (vs. never) users were more likely to report past 6-month use of any combustible tobacco product at the 6-month (30.7% vs. 8.1%, % difference [95% CI]=22.7[16.4, 28.9]) and 12-month (25.2% vs. 9.3%, % difference [95% CI]= 15.9[10.0, 21.8]) follow-ups (see Table 3). As shown in the “Any Tobacco Product” column of GLMM results reported in Table 4, the unadjusted estimate for the association of ever use of e-cigarettes with any combustible tobacco use averaged across the two follow-ups was statistically significant (OR[95% CI]=4.27[3.19, 5.71]). In this model, the estimate for time of data collection was not significant (OR[95% CI]=1.09[0.90, 1.32]), indicating no change in the prevalence of combustible tobacco use across the 6- and 12-month follow-ups. The e-cigarette × time interaction was not significant (OR[95% CI]=0.64[0.39, 1.04]), indicating that the strength of association between baseline e-cigarette use and combustible tobacco use did not significantly differ between the 6-month and 12-month follow-ups. In the adjusted GLMM, baseline e-cigarette ever-use was associated with any combustible tobacco product use averaged across the two follow-ups over and above the covariates (OR[95% CI]=2.73[2.00, 3.73]). Parameter estimates for covariates in adjusted GLMMs indicated that lower parental education and baseline peer smoking, impulsivity, ever use of non-nicotine/tobacco substances, delinquent behavior, and smoking expectancies were positively associated with any combustible tobacco use averaged across the two follow-ups (see Table 4, eTable 2). These particular covariates were also associated with baseline e-cigarette ever use (Table 1).

Table 3.

Prevalence of Past 6-month Combustible Tobacco Use at 6- and 12-Month Follow-Ups by Baseline E-Cigarette Ever Use Among Baseline Never-Smokers

| Use in the Prior 6 months |

|

Baseline E-Cigarette Use

|

Difference in Prevalence Rates

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N=2,530) |

Never Use (N=2,308) |

Ever Use (N=222) |

% (95%CI) | P Value | |

| 6-Month Follow-Up | |||||

| Any Combustible Tobacco Product, n (%) | 249 (10.1%)a | 182 (8.1%) | 67 (30.7%) | 22.7 (16.4, 28.9) | <.001* |

| Combustible Cigarettes, n (%) | 89 (3.6%)b | 68 (3.0%) | 21 (9.7%) | 6.7 (2.7, 10.7) | <.001* |

| Cigars, n (%) | 107 (4.4%)c | 70 (3.1%) | 37 (17.3%) | 14.2 (9.0, 19.3) | <.001* |

| Hookah, n (%) | 160 (6.6%)d | 122 (5.5%) | 38 (17.8%) | 12.3 (7.1, 17.5) | <.001* |

| Number of Different Combustible Tobacco | – | – | – | – | <.001* |

| Products, n (%) | |||||

| 0 products | 2,223 (89.9%) | 2,072 (91.9%) | 151 (69.3%) | ||

| 1 product | 166 (6.7%) | 122 (5.4%) | 44 (20.2%) | ||

| 2 products | 59 (2.4%) | 42 (1.9%) | 17 (7.8%) | ||

| 3 products | 24 (1.0%) | 18 (0.8%) | 6 (2.8%) | ||

| 12-Month Follow-Up | |||||

| Any Combustible Tobacco Product, n (%) | 264 (10.7%)e | 210 (9.3%) | 54 (25.2%) | 15.9 (10.0, 21.8) | <.001* |

| Combustible Cigarettes, n (%) | 91 (3.7%)f | 74 (3.3%) | 17 (7.9%) | 4.7 (1.0, 8.4) | <.001* |

| Cigars, n (%) | 126 (5.3%)g | 93 (4.3%) | 33 (16.2%) | 11.9 (6.8, 17.0) | <.001* |

| Hookah, n (%) | 152 (6.4%)h | 127 (5.9%) | 25 (12.3%) | 6.4 (1.8, 11.0) | <.001* |

| Number of Different Combustible Tobacco | – | – | – | – | <.001* |

| Products, n (%) | |||||

| 0 products | 2,198 (89.3%) | 2,038 (90.7%) | 160 (74.8%) | ||

| 1 product | 181 (7.4%) | 143 (6.4%) | 38 (17.8%) | ||

| 2 products | 61 (2.5%) | 50 (2.2%) | 11 (5.1%) | ||

| 3 products | 22 (0.9%) | 17 (0.8%) | 5 (2.3%) | ||

Note. Due to missing data for each respective variable, denominators are

N=2,473,

N=2,468,

N=2,443,

N=2,434,

N=2,463,

N=2,462,

N=2,374,

N=2,371.

Chi-square test.

Table 4.

Association of Baseline E-Cigarette Ever Use and Covariates to Combustible Tobacco Use Outcomes at 6- and 12-Month Follow Ups among Baseline Never-Smokers

| Outcome

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Tobacco Producta

|

Combustible Cigarettesb

|

Cigarsc

|

Hookahd

|

Number of Tobacco Productse

|

||||||

| Baseline Regressors and Covariates | OR(95%CI)f | P | OR(95%CI)f | P | OR(95%CI)f | P | OR(95%CI)f | P | OR(95%CI)g | P |

| Unadjusted Models | ||||||||||

| E-cigarette ever (vs. never) use | 4.27 (3.19, 5.71) | <.001 | 2.65 (1.73, 4.05) | <.001 | 4.85 (3.38, 6.96) | <.001 | 3.25 (2.29, 4.62) | <.001 | 4.26 (3.16, 5.74) | <.001 |

| Time (12- vs. 6-month follow-up) | 1.09 (0.90, 1.32) | .38 | 1.03 (0.76, 1.39) | .85 | 1.25 (0.95, 1.64) | .11 | 0.99 (0.78, 1.25) | .90 | 1.08 (0.89, 1.30) | .45 |

| Ever e-cigarette use × Timeh | 0.64 (0.39, 1.04) | .07 | 0.73 (0.34, 1.56) | .41 | 0.68 (0.36, 1.26) | .22 | 0.60 (0.32, 1.12) | .11 | 0.64 (.039, 1.03) | .07 |

| Adjusted Models | ||||||||||

| Categorical covariatesi | ||||||||||

| Female (vs. male) | 0.88 (0.70, 1.11) | .28 | 1.50 (1.05, 2.15) | .03 | 1.48 (1.06, 2.06) | .02 | 0.67 (0.51, 0.90) | .007 | 0.92 (0.73, 1.17) | .52 |

| Hispanic (vs. other) ethnicity | 1.09 (0.82, 1.44) | .55 | 0.91 (0.59, 1.39) | .65 | 0.97 (0.66, 1.43) | .87 | 1.33 (0.97, 1.83) | .08 | 1.11 (0.83, 1.48) | .48 |

| Lives with both biological parents (vs. other living situation) | 0.80 (0.64, 1.01) | .07 | 0.96 (0.67, 1.37) | .80 | 0.58 (0.42, 0.80) | <.001 | 0.82 (0.62, 1.08) | .15 | 0.80 (0.63, 1.01) | .06 |

| Substance ever (vs. never) use | 2.33 (1.81, 2.99) | <.001 | 1.35 (0.91, 2.00) | .14 | 2.42 (1.72, 3.42) | <.001 | 2.25 (1.67, 3.01) | <.001 | 2.24 (1.73, 2.90) | <.001 |

| Family history of smoking (yes vs. no) | 1.11 (0.88, 1.41) | .37 | 1.34 (0.91, 1.98) | .14 | 0.95 (0.68, 1.32) | .75 | 0.99 (0.74, 1.32) | .94 | 1.11 (0.87, 1.42) | .39 |

| Continuous covariatesj | ||||||||||

| Age | 1.07 (0.96, 1.20) | .23 | 1.13 (0.96, 1.34) | .15 | 1.12 (0.95, 1.31) | .17 | 0.97 (0.84, 1.11) | .64 | 1.07 (0.95, 1.20) | .27 |

| Parental education | 0.83 (0.73, 0.94) | .004 | 0.81 (0.67, 0.97) | .03 | 0.88 (0.72, 1.06) | .18 | 0.86 (0.74, 1.01) | .07 | 0.83 (0.73, 0.95) | .007 |

| Peer smoking | 1.13 (1.00, 1.28) | .05 | 1.08 (0.90, 1.30) | .41 | 1.18 (1.00, 1.38) | .05 | 1.16 (1.01, 1.34) | .03 | 1.13 (1.00, 1.28) | .05 |

| CESD-Depressive Symptoms | 0.95 (0.84, 1.08) | .42 | 1.07 (0.89, 1.29) | .45 | 0.97 (0.81, 1.15) | .70 | 0.99 (0.85, 1.14) | .87 | 0.97 (0.86, 1.10) | .66 |

| TCI-Impulsivity | 1.23 (1.09, 1.38) | <.001 | 1.11 (0.93, 1.33) | .25 | 1.14 (0.97, 1.35) | .11 | 1.28 (1.11, 1.46) | <.001 | 1.22 (1.09, 1.38) | <.001 |

| Delinquent Behavior | 1.38 (1.18, 1.61) | <.001 | 1.35 (1.10, 1.66) | .004 | 1.39 (1.14, 1.70) | .001 | 1.38 (1.14, 1.66) | <.001 | 1.40 (1.20, 1.63) | <.001 |

| Smoking susceptibility | 1.08 (0.92, 1.26) | .37 | 1.46 (1.18, 1.80) | <.001 | 0.98 (0.79, 1.21) | .84 | 0.94 (0.77, 1.14) | .53 | 1.09 (0.93, 1.29) | .28 |

| Smoking expectancies | 1.24 (1.10, 1.41) | <.001 | 1.19 (0.98, 1.44) | .08 | 1.43 (1.20, 1.69) | <.001 | 1.26 (1.08, 1.46) | .003 | 1.27 (1.12, 1.44) | <.001 |

| Regressors | ||||||||||

| E-cigarette ever (vs. never) use | 2.73 (2.00, 3.73) | <.001 | 1.75 (1.10, 2.77) | .02 | 2.96 (2.00, 4.38) | <.001 | 2.26 (1.56, 3.29) | <.001 | 2.73 (1.99, 3.75) | <.001 |

| Time (12- vs. 6-month follow-up) | 1.09 (0.90, 1.33) | .37 | 1.03 (0.76, 1.40) | .85 | 1.26 (0.95, 1.67) | .10 | 0.98 (0.77, 1.24) | .84 | 1.08 (0.89, 1.32) | .42 |

| Ever e-cigarette use × Timeh | 0.64 (0.38, 1.05) | .08 | 0.74 (0.34, 1.61) | .44 | 0.68 (0.36, 1.29) | .23 | 0.59 (0.31, 1.12) | .11 | 1.54 (0.94, 2.51) | .08 |

Note. All analyses include only never-users of combustible tobacco products at baseline. -2 Res Log Pseudo-Likelihood fit index for unadjusted models without the interaction term:

24,932.93,

28,391.21,

27,019.65,

26,131.31,

70,339.66. -2 Res Log Pseudo-Likelihood fit index for unadjusted models with the interaction term:

24,946.6,

28,397.11,

27,050.36,

26,137.37,

70,411.89. Range of -2 Res Log Pseudo-Likelihood fit indices for adjusted models without the interaction term across the five imputed data sets:

25,701.9 – 25,743.77,

29,378.05 – 29,461.92,

28,211.45 – 28,286.11,

27,193.74 – 27,282.15,

73,652.58 – 73,852.15. Range of -2 Res Log Pseudo-Likelihood fit indices for adjusted models with the interaction term across the five imputed data sets:

25,717.24 – 25,759.27,

29,382.85 – 29,467.24,

28,238.77 – 28,312.83,

27,209.93 – 27,297.96,

73,730.36 – 73,930.47.

OR from repeated binary logistic regression model predicting respective outcome from baseline ever e-cigarette use status (yes/no) including school fixed effects.

OR from repeated ordinal logistic regression model predicting respective outcome from baseline ever e-cigarette use status (yes/no) including school fixed effects, with the OR reflecting the change in odds of being in a category with use of one or more tobacco products (3 vs. ≤2; ≥2 vs. ≤1, ≥1 vs. 0) associated with the covariate/regressor.

Interaction term added in subsequent model; parameter estimates for other regressors/covariates are from model excluding the interaction term.

Prevalance of combustible tobacco use outcomes at follow-ups by status on the categorical covariates can be found in eTable 2.

Continuous covariates rescaled (M=0, SD=1), such that the ORs indicate the change in odds in the outcome associated with an increase in one standard deviation unit on the covariate continuous scale. CESD = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. TCI = Temperament and Character Inventory.

As depicted in Table 3, baseline e-cigarette ever (vs. never) use was also positively associated with increased likelihood of combustible cigarette smoking (6-month follow up: 9.7% vs. 3.0%, % difference [95% CI]=6.7[2.7, 10.7]; 12-month follow-up: 7.9% vs. 3.3%, % difference [95% CI]=4.7[1.0, 8.4]), cigar use (6-month follow-up: 17.3% vs. 3.1%, % difference [95% CI]=14.2[9.0, 19.3]; 12-month follow up: 16.2% vs. 4.3%, % difference [95% CI]=11.9[6.8, 17.0]), and hookah use (6-month follow-up: 17.8% vs. 5.5%, % difference [95% CI]=12.3[7.1, 17.5]; 12-month follow-up: 12.3% vs. 5.9%, % difference [95% CI]=6.4[1.8, 11.0]). Averaged across the two follow-ups, the association of baseline e-cigarette ever-use with use of specific tobacco products during follow-ups in unadjusted GLMMs was as follows: combustible cigarettes (OR[95% CI]= 2.65[1.73, 4.05]), cigars (OR[95% CI]= 4.85[3.38, 6.96]), and hookah (OR[95% CI]= 3.25[2.29, 4.62]). Additionally, relative to baseline e-cigarette never-users, e-cigarette ever-users were more likely to be using at least one more combustible tobacco product (i.e., 3 vs. ≤2; ≥2 vs. ≤1, ≥1 vs. 0) averaged across the two follow-up assessments (OR[95% CI]= 4.26[3.16, 5.74]). Each OR estimate for e-cigarette ever-use remained significant in the adjusted models and after applying the Bonferroni-Holm correction for multiple comparisons. The OR magnitudes for e-cigarette ever-use were reduced from unadjusted to adjusted models for each outcome, and a common set of covariates (peer smoking, impulsivity, ever use of non-nicotine/tobacco substances, delinquent behavior, and smoking expectancies) were associated with most outcomes in adjusted GLMMs (see Table 4, eTable 2). Time and the e-cigarette × time interaction were non-significant in all models, suggesting no change in each outcome’s prevalence rate or degree of association with baseline e-cigarette use across the two follow-ups. Additional results can be found in the eSensitivity Analyses appearing in the online only supplement.

Supplementary Analyses

Using the same modeling strategy as applied for the primary analysis, the association between baseline combustible tobacco ever-use and past 6-month use (initiation) of e-cigarettes at the follow-ups was analyzed. These analyses included ever-smokers at baseline but excluded ever-users of e-cigarettes in order to model initiation of e-cigarette use. Baseline ever-use of each combustible tobacco product was positively associated with e-cigarette use averaged across the follow-ups in unadjusted and adjusted GLMMs, except for cigars in the adjusted model (P=.06; eTables 3 – 5).

DISCUSSION

These data provide new evidence that e-cigarette use is prospectively associated with increased risk of combustible tobacco use initiation during early adolescence. Associations were consistent across unadjusted and adjusted models, multiple tobacco product outcomes, and various sensitivity analyses. Based on these data, it is unlikely that the high prevalence of adolescent dual users of e-cigarettes and combustible tobacco reported in recent national cross-sectional surveys2,3 is entirely accounted for by adolescent smokers who later initiate e-cigarette use. Supplementary analyses showed that adolescents who ever (vs. never) smoked at baseline were more likely to initiate e-cigarette use during the follow-up period. Collectively, these results raise the possibility that the association between e-cigarette and combustible tobacco use initiation may be bi-directional.

During the age period captured in this study (fall 9th grade to fall 10th grade), adolescents adjust to the transition from middle school to high school, which is often accompanied by movement to a school with a larger, more diverse student body, new social contexts, increased exposure to older adolescents, and new academic demands.4 Early adolescence is also a period of uneven brain development in which neural circuits that underlie motivation to seek out novel experiences develop more rapidly than circuits involving impulse control and effective decision-making.25 Consequently, the expression of a propensity to initiate combustible tobacco use may be heightened during this age period.

The observed association between e-cigarette use and combustible tobacco use initiation may be explained by several mechanisms. It is possible that common risk factors for both e-cigarette and combustible tobacco use are responsible for the use of these two products and the order of onset of e-cigarette use relative to combustible tobacco use may not be determined by a causal sequence. Some teens may be more likely to use e-cigarettes prior to combustible tobacco because of beliefs that e-cigarettes are not harmful or addictive,26,27 youth-targeted marketing,28 availability of e-cigarettes in flavors attractive to youths,27,28 and ease of accessing e-cigarettes due to either an absence or inconsistent enforcement of restrictions against sales to minors.29 We attempted to analytically address the possible influence of shared risk factors by adjusting for sociodemographic, environmental, and intrapersonal characteristics that presumably could affect use of both types of products. Adjusting for these factors reduced the OR estimates associated with e-cigarette use. Still, in the adjusted models baseline e-cigarette ever use was associated with a significant increase in odds of smoking initiation that ranged from 1.75 to 2.96, depending on the outcome.

While it remains possible that factors not accounted for in this study may explain the association between e-cigarette use and combustible tobacco use initiation, it is also plausible that exposure to e-cigarettes, which have evolved to become effective nicotine delivery devices, may play a role in risk of smoking initiation. Newer generation e-cigarette devices with higher voltage batteries and efficient machinery have been shown to heat e-cigarette solutions to high temperatures, which results in nicotine-rich aerosols that effectively and quickly deliver nicotine to the user, generating desirable psychoactive effects that may carry abuse liability.30,31 The neurodevelopmental and social backdrop of early adolescence may promote risk-taking behavior25 and neural plasticity may sensitize the adolescent brain to the effects of nicotine.32 Hence, adolescent never-smokers exposed to nicotine-rich e-cigarette aerosols and the pleasant sensations associated with vaping could be more liable to experiment with other nicotine-containing products, including combustible tobacco. Because this is an observational study and one of the first to address this issue, inferences regarding whether this association is or is not causal cannot yet be made.

The study has several strengths, including a demographically diverse sample, repeated measures of tobacco use, exclusion of ever-smokers at baseline, high follow-up rate, comprehensive assessment of multiple combustible tobacco products, and statistical control for important covariates. A limitation of the study is that e-cigarette use was measured only as “any use” and product characteristics (e.g., nicotine strength and flavor) were not assessed. Thus, whether a specific frequency or type of e-cigarette use is associated with the initiation of combustible tobacco could not be determined. This study focuses solely on initiation outcomes; future research should evaluate whether e-cigarette use is associated with increased risk of escalating to regular, frequent combustible tobacco use. The current sample was drawn from a specific location, which may restrict generalizability. The age period focused on in this study captured an important, but brief, window of susceptibility. In this and other samples,2,3 youths commonly initiated combustible tobacco use prior to 9th grade and e-cigarette use after 9th grade, suggesting that investigating other ages is warranted. Some important covariates (e.g., advertising exposure, sensation seeking, and academic performance) were not assessed and should be included in future work.

CONCLUSIONS

Among high school students in Los Angeles, those who used electronic cigarettes at baseline compared with nonusers were more likely to report initiation of combustible tobacco use over the next year. Further research is needed to understand whether this association may be causal.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-DA033296 and P50-CA180905; the funding agency had no role in the design or execution of the study.

Role of Funder: The funding agency had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors report no potential conflicts of interests

Author contributions: AML conducted the analyses and was principal investigator responsible for study conception and directing data collection. AML and JAM lead the conceptualization of the study and wrote the majority of the manuscript text. DRS, MGK, NRR, SS, JBU, MS, RK, and JS aided in study conceptualization and provided feedback on drafts. MS and RK oversaw data management and processing.

Access to Data and Data Analysis: The corresponding author (AML) had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Benowitz NL. Pharmacology of nicotine: addiction, smoking-induced disease, and therapeutics. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2009;49:57–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. Trends in the Prevalence of Tobacco Use National YRBS: 1991–2013. 2015 http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/yrbs/pdf/trends/us_tobacco_trend_yrbs.pdf.

- 3.Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Use of alcohol, cigarettes, and number of illicit drugs declines among US teens 2015. 2015 http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/data/14data.html-2014data-cigs. Accessed April 3, 2015.

- 4.Benner AD. The Transition to High School: Current Knowledge, Future Directions. Educational psychology review. 2011;23(3):299–328. doi: 10.1007/s10648-011-9152-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2010;59(5):1–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Overview: Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2015. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use 1975–2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Tercyak KP, Cuevas J, Rodgers K, Patterson F. Identifying and characterizing adolescent smoking trajectories. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(12):2023–2034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. J Youth Adolesc. 1991;20(2):149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strong DR, Hartman SJ, Nodora J, et al. Predictive Validity of the Expanded Susceptibility to Smoke Index. Nicotine & tobacco research: official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2015;17(7):862–869. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camenga DR, Kong G, Cavallo DA, et al. Alternate tobacco product and drug use among adolescents who use electronic cigarettes, cigarettes only, and never smokers. The Journal of adolescent health: official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2014;55(4):588–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper ZD, Haney M. Comparison of subjective, pharmacokinetic, and physiological effects of marijuana smoked as joints and blunts. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2009;103(3):107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Covey LS, Tam D. Depressive mood, the single-parent home, and adolescent cigarette smoking. American journal of public health. 1990;80(11):1330–1333. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.11.1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tyas SL, Pederson LL. Psychosocial factors related to adolescent smoking: a critical review of the literature. Tobacco control. 1998;7(4):409–420. doi: 10.1136/tc.7.4.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardenas VM, Breen PJ, Compadre CM, et al. The smoking habits of the family influence the uptake of e-cigarettes in US children. Annals of epidemiology. 2015;25(1):60–62. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wills TA, Knight R, Williams RJ, Pagano I, Sargent JD. Risk factors for exclusive e-cigarette use and dual e-cigarette use and tobacco use in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):e43–51. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kong G, Morean ME, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S. Reasons for Electronic Cigarette Experimentation and Discontinuation Among Adolescents and Young Adults. Nicotine & tobacco research: official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2015;17(7):847–854. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CDC. National Youth Tobacco Survey Methodology Report. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control & Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cloninger C, Przybeck T, Syrakic D, Wetzel R. The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI): A guide to its development and use. St. Louis, MO: Center for Psychobiology of Personality, Washington University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson MP, Ho CH, Kingree JB. Prospective associations between delinquency and suicidal behaviors in a nationally representative sample. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(3):232–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz EC, Fromme K, D’Amico EJ. Effects of outcome expectancies and personality on young adults’ illicit drug use, heavy drinking, and risky sexual behavior. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2000;24:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCulloch C, Searle S. Generalized Linear Mixed Models. New York, NY USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inc SI. SAS® 9.3 System Options: Reference Vol Second Edition. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinberg L. A Social Neuroscience Perspective on Adolescent Risk-Taking. Developmental review: DR. 2008;28(1):78–106. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peters RJ, Meshack A, Lin MT, Hill M, Abughosh S. The social norms and beliefs of teenage male electronic cigarette use. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2013;12(4):300–307. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2013.819310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kong G, Morean ME, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S. Reasons for Electronic Cigarette Experimentation and Discontinuation Among Adolescents and Young Adults. Nicotine & tobacco research: official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2014 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gostin LO, Glasner AY. E-cigarettes, vaping, and youth. Jama. 2014;312(6):595–596. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collaco JM, Drummond MB, McGrath-Morrow SA. Electronic cigarette use and exposure in the pediatric population. JAMA pediatrics. 2015;169(2):177–182. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.2898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vansickel AR, Eissenberg T. Electronic cigarettes: effective nicotine delivery after acute administration. Nicotine & tobacco research: official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2013;15(1):267–270. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shihadeh A, Eissenberg T. Electronic cigarette effectiveness and abuse liability: predicting and regulating nicotine flux. Nicotine & tobacco research: official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2015;17(2):158–162. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Counotte DS, Smit AB, Pattij T, Spijker S. Development of the motivational system during adolescence, and its sensitivity to disruption by nicotine. Developmental cognitive neuroscience. 2011;1(4):430–443. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.