Abstract

Background

This study examined whether relocating from a high-poverty neighborhood to a lower poverty neighborhood as part of a federal housing relocation program (HOPE VI; Housing Opportunities for People Everywhere) had effects on adolescent mental and behavioral health compared to adolescents consistently living in lower poverty neighborhoods.

Methods

Sociodemographic, risk behavior, and neighborhood data were collected from 592 low-income, primarily African American adolescents and their primary caregivers. Structured psychiatric interviews were conducted with adolescents. Pre-relocation neighborhood, demographic, and risk behavior data were also included. Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) was used to test associations between neighborhood variables and risk outcomes. HLM was used to test whether the effect of neighborhood relocation and neighborhood characteristics might explain differences in sexual risk taking, substance use, and mental health outcomes.

Results

Adolescents who relocated out of HOPE VI neighborhoods (n= 158) fared worse than control group participants (n= 429) on most self-reported mental health outcomes. The addition of subjective neighborhood measures generally did not substantively change these results.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that moving from a high-poverty neighborhood to a somewhat lower poverty neighborhood is not associated with better mental health and risk behavior outcomes in adolescents. The continued effects of having grown up in a high-poverty neighborhood, the small improvements in their new neighborhoods, the comparatively short length of time they lived in their new neighborhood, and/or the stress of moving appears to worsen most of the mental health outcomes of HOPE VI compared to control group participants who consistently lived in the lower poverty neighborhoods.

Keywords: adolescent, housing relocation, sexual risk-taking, mental health, substance abuse

The relationship between neighborhood poverty or socioeconomic status and mental health is well established (Kessler et al., 2012; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Leventhal, Dupere, & Brooks-Gunn, 2009; Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, 2002). Research suggests that specific aspects of the neighborhood environment, such as physical and social disorder, low collective efficacy, and exposure to violence, may have a negative effect on adolescent mental health and increase engagement in risky behaviors (Aneshensel & Sucoff, 1996; Gorman-Smith, Tolan, & B. Henry, 2000; Lang et al., 2010; Nebbitt, Lombe, Sanders-Phillips, & Stokes, 2010; Overstreet, 2000; Voisin, Jenkins, & Takahashi, 2011). Protective aspects of neighborhoods are also important, including neighborhood support and collective efficacy, which are associated with lower levels of individual adolescent problem behaviors, including conduct problems, substance use, and risky sexual behavior (Brody et al., 2003; Widome, Sieving, Harpin, & Hearst, 2008). A review of studies by Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn (2000) found that neighborhood disadvantage was associated with greater conduct problems in childhood and adolescence. Aneshensel and Sucoff (1996) reported that more threatening neighborhoods, according to adolescent perceptions, were associated with more common symptoms of conduct problems, oppositional defiant disorder, depression and anxiety. Exposure to violence in the community has been found to increase intentions to commit violence, as well as other risky behaviors (DuRant et al., 2000; DuRant, Treiber, Goodman, & Woods, 1996).

In addition to affecting mental health, neighborhood research has also found associations with adolescent sexual health, particularly for girls (Leventhal et al., 2009). Living in disadvantaged neighborhoods has been linked to risky sex behaviors and higher rates of teenage childbearing (Browning, Leventhal, & Brooks-Gunn, 2004; Sucoff & Upchurch, 1998). Research on Chicago neighborhoods found that low social capital, social cohesion, social control, and collective efficacy, and high social disorder were linked with high rates of STIs (Thomas, Torrone, & Browning, 2010). Cohen et al. (2000) also found strong evidence for the relationship between physical neighborhood disorder (i.e., “broken windows”) and gonorrhea rates. Another study found higher rates of gonorrhea among high school students in New Orleans living in neighborhoods still showing deterioration after Hurricane Katrina (Nsuami, Taylor, Smith, & Martin, 2009).

Researchers and policymakers have been interested in whether moving from more to less disadvantaged neighborhoods positively impacts adolescent mental health and reduces engagement in risk behaviors. The Moving to Opportunity (MTO) study provides most of the knowledge on this topic (Gennetian et al., 2012; Leventhal & Dupere, 2011). The MTO was a randomized experiment in five U.S. cities in which families living in public housing were offered housing vouchers and assistance to move to lower-poverty neighborhoods. Studies of the long-term effects of MTO on youth outcomes show that girls in the experimental group experienced fewer mental health problems (Kessler et al., 2014), perhaps related to a reduced fear of sexual victimization (Popkin, Leventhal, & Weismann, 2010), but there were few effects for youth in general in terms of risky behaviors (Gennetian et al., 2012). Boys in the MTO study either showed worsening or no change in risk behaviors and mental health outcomes (Clampet-Lundquist, Kling, Edin, & Duncan, 2011; Gennetian et al., 2012; Kessler et al., 2014; Osypuk, Schmidt, et al., 2012; Osypuk, Tchetgen, et al., 2012). While MTO represents the only U.S. randomized housing relocation study of its kind and had substantial methodological strengths, there were still limitations, including that (a) participation was voluntary, meaning that there were self-selection issues (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2003); and (b) that it was an individual-level intervention (i.e., for families offered housing vouchers) rather than a neighborhood-level intervention (i.e., an entire housing development selected) so generalizations cannot be made about the program at the neighborhood level (Sampson, 2008). Not every family was offered a housing voucher and not every family that received a voucher chose to move; both of these implications introduced bias into the sample.

In addition to the MTO study, research on housing relocation also comes from studies of the Housing Opportunities for People Everywhere (HOPE VI) federal public housing revitalization program. When a HOPE VI program involves demolition of a subset of public housing along with vouchers for families to relocate to neighborhoods that meet particular standards, it represents a form of “natural experiment.” Such natural experiments allow for the evaluation of independent effects of neighborhood characteristics on health outcomes by removing the confound of selection effects (i.e., neighborhood quality is not randomly distributed, but rather related to a number of other individual factors related to health), but such opportunities are very rare and difficult to realize (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2003, 2004; Rosenbaum & Popkin, 1991). The original intent of the national HOPE VI program was to move families to less disadvantaged neighborhoods and build more sustainable communities, although this objective has often been difficult to achieve (Popkin et al., 2004). While HOPE VI program implementation and details varied by location, research generally shows that (1) people moved to nearby, lower poverty neighborhoods, (2) the new neighborhoods were generally still disadvantaged, and (3) the new neighborhoods were as racially segregated as their original neighborhoods. Residents reported feeling safer in their new neighborhoods, but still experienced substantial residential instability, loss of social support, limited or no improvement in educational and employment opportunities, and little or modest improvements in adult and youth physical and mental health outcomes (Oakley, Ruel, & Reid, 2013).

The Current Study

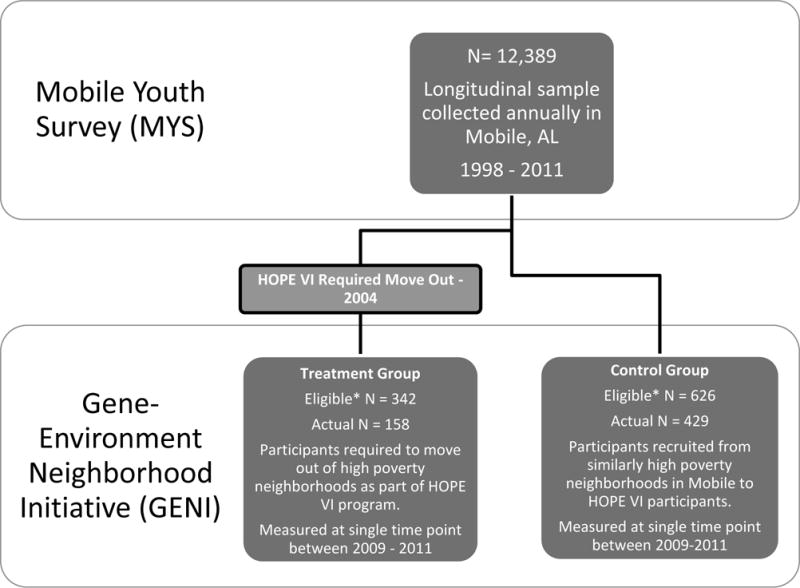

The current study, known as the Gene, Environment, Neighborhood Initiative (GENI), included a community sample of 592 adolescents aged 13 through 18 and their primary caregivers. The adolescents and caregivers were from predominantly African American, very disadvantaged neighborhoods in Mobile, Alabama. Interviews were conducted with participants who were a subsample recruited from the larger Mobile Youth Study (MYS; see Figure 1), a community-based, multiple cohort longitudinal study with annual data collection from 1998–2011, which has been described in detail elsewhere (Bolland, 2007; Park, Lee, Bolland, Vazsonyi, & Sun, 2008). The purpose of GENI was to study a HOPE VI program in which federal housing funds were used to relocate a group of families living in public housing in a southeastern U.S. city to lower poverty neighborhoods. GENI addresses an important limitation of many housing relocation studies because the link to MYS provided pre-relocation data; therefore, we could determine whether there were substantial differences between the control and treatment groups prior to moving. It also improved upon randomized housing relocation experiments in that all families in this HOPE VI program were required to move. We hypothesized that relocating from a high-poverty neighborhood to a lower poverty neighborhood would have a positive effect on adolescent mental health as well as other risk behaviors.

Figure 1. Association between GENI and MYS.

Note: *Eligible participants in the Treatment Group are all MYS participants who participated in the HOPE VI program. In the Control Group, eligible participants are all MYS participants from equivalent high poverty neighborhoods in the same age range as Treatment Group eligible participants.

Methods

Participation in GENI involved an approximately two and a half hour interview for both the adolescent and his/her caregiver. Whenever possible, measures were collected using an audio computerized self-administered interview (ACASI) approach, which removed the need for interviewers to ask sensitive questions, or through interviewer-administered questionnaires for less sensitive measures. Written parental consent and youth assent were obtained. Caregivers and adolescents were compensated for their participation. Procedures for this study were approved by the Institutional Review Boards.

Measures

Study data were from the GENI interviews except for MYS Neighborhood Measures and U.S. Census Data. When MYS data were used, it was only used for participants who were also part of the GENI subsample.

We used the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (C-DISC) version 4.0 to assess Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) diagnoses. The C-DISC is a widely used assessment of psychiatric diagnoses among adolescents and is administered as a computerized, structured interview by trained lay interviewers to the adolescent. We report on symptom counts for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) (range: 0–20) and Conduct Disorder (CD) (range: 0–19) for the previous 12 month period. The acceptable reliability and validity of the computerized DISC 4.0 and earlier versions has been well-described (Shaffer, Fisher, & Lucas, 2004; Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000).

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and the Youth Self-Report (YSR) were used to assess symptoms of psychopathology. The CBCL was completed by a parent or caregiver and the YSR by the adolescent. The internalizing scale (range: CBCL 0–46, YSR 0–40) is the sum of scores from the anxious/depressed, withdrawn/depressed, and somatic/complaints syndrome scales, while the externalizing scale (range: CBCL 0–63, YSR 0–59) is the sum of the rule-breaking behavior and aggressive behavior syndromes. The CBCL and YSR are reliable and valid (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) and have been used in many diverse samples. We present results for the internalizing and externalizing scales.

The HIV-Risk Assessment for Sexual Partnerships (H-RASP) is a computerized self-administered interview designed to assess sexual behavior and associated situational and contextual variables at the level of the sexual partnership (i.e., partner-by-partner) (Mustanski, Starks, & Newcomb, 2013). The H-RASP was used to assess sexual risk-taking, including number of partners, condom use, and drinking and substance use before sex.

The AIDS-Risk Behavior Assessment (ARBA) was derived from five well-established measures used in large-scale studies to examine drug use and other risk-taking behaviors in youth (Dowling, Johnson, & Fisher, 1994; IBS, 1991; Needle et al., 1995; NIDA, 1995; Watters, 1994; Weatherby, Needle, & Cesari, 1994) and was used to collect data on alcohol (range: 0–24) and marijuana use (range: 0–7).

Neighborhood Ecology

This measure was adapted from the 14-item Neighborhood Problems scale used in the Chicago Youth Development Study (CYDS) (Gorman-Smith et al., 2000). Both adolescents and caregivers were asked about their neighborhood and relationships with their neighbors. The Neighborhood Ecology scale includes subscales based on the physical (e.g., “There is too much graffiti in my neighborhood”) and social (e.g., “There is too much drug use in my neighborhood”) environment. Higher scores indicated worse neighborhood ecology. Reliability for both adolescent report (total: α = .83; physical α = .71; social α = .82) and caregiver report (total: α = .85; physical α = .74; social α = .81) was good.

The Collective Efficacy scales administered to adolescents and caregivers included (1) Informal Social Control (ISC), which had four items for adolescents and five items for caregivers (e.g., “How likely is it that your neighbors would get involved or intervene if children were skipping school and hanging out on a street corner?“); and (2) the five item Social Cohesion and Trust (SCT) scale (e.g., “How strongly do you agree with the statement ‘People around here are willing to help their neighbors?’) (Morenoff, Sampson, & Raudenbush, 2001; Sampson & Raudenbush, 1997). Higher scores indicated a lower level of collective efficacy. Reliability was good for the total scale (α =.70 for adolescents, .84 for caregivers) and acceptable for the subscales given the small number of items (ISC: α =.85 for adolescents, .86 for caregivers; SCT: α =.60 for adolescents, .66 for caregivers).

The Exposure to Violence scale included nine questions adapted from the CYDS scale of the same name. Adolescent participants and their caregivers were asked about victimization and witnessing violence, ever or in the last 12 months (e.g., “Have you EVER/In the LAST 12 MONTHS seen anyone get beat up in your neighborhood?”) (Gorman-Smith & Tolan, 1998). Reliability was good for both adolescent (α = .76 for both ever exposed and exposed in last 12 months) and caregiver (α = .71 for ever exposed, α = .65 for exposed in last 12 months) reports. Higher scores indicated a greater exposure to violence.

MYS Neighborhood Measures

These data were collected as part of the MYS. At every time point on the MYS, participants were asked a single item about neighborhood safety (“How much of the time do you feel unsafe in your neighborhood?”) with response options “Never”, “Sometimes”, “Most of the time, but not all the time”, and “All the time.” Participants were also asked to agree or disagree with a single item about fights in their neighborhood (“It is not possible to avoid fights in my neighborhood”). We assessed attachment to neighborhood and feelings of support in the neighborhood using a mean composite of an 11-item scale with dichotomous items (α = .55) (e.g., “It is hard to make good friends in my neighborhood”). Difference scores were calculated for adolescent GENI participants using their MYS data for neighborhood safety, neighborhood fighting, and feelings about neighborhood using the last pre-move data in 2004 and the first post-move data in 2006. Because these difference scores are based on adolescent’s perceptions of their pre and post-move neighborhoods, they were treated as individual level variables rather than aggregated up to the neighborhood level.

U.S. Census Data

Using methods described in a review of how neighborhood affects youth health and well-being (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000), we used 2000 and 2010 U.S. Census data in combination with participant reported addresses to objectively assess neighborhood environment. We formed factor scores based on low socioeconomic status (SES; percentage of unemployed residents, families living below the poverty line, families headed by a single parent, and households receiving public assistance), high SES (percentage of residents with a college degree, residents classified as professional or management, families with income of $75,000 or higher, and median family income), residential stability (percentage of residents in the same home since 1995 and percentage of housing units that are owner occupied) and racial makeup (percentage of African American residents) for each participant based on their location.

Treatment and Control Groups

HOPE VI participants were initially recruited based on neighborhood data reported in the MYS. The control sample was also recruited from MYS from neighborhoods equivalent to those that were part of HOPE VI (see Figure 1). We obtained data for confirming membership in the treatment (HOPE VI) or control groups from several sources: caregiver report of addresses the adolescent(s) lived at since January 2004; records from the Mobile County Public School System (MCPSS); and records from the Mobile Housing Board (MHB). Due to discrepancies between addresses from the caregiver report and addresses used to identify and recruit HOPE VI participants, we used MCPSS and MHB to verify participant addresses. There were 342 eligible participants from the MYS who participated in HOPE VI and 626 MYS participants from equivalently high poverty neighborhoods, of which we recruited 158 (46.20%) to the treatment condition and 434 (69.33%) to the control condition, respectively. The primary reason eligible participants were not recruited into GENI was because we were unable to locate them (85.67%), followed by participants declining (5.21%), and participant incarcerations at the time of the GENI interview (2.28%). Addresses for the HOPE VI group and control group participants were geocoded, allowing us to link neighborhood of residence with U.S. census tract and block data. Based on U.S. Census data, almost all of the HOPE VI youth relocated to less disadvantaged neighborhoods; however, by national standards, these new neighborhoods were still disadvantaged, just less so than the original HOPE VI neighborhood (Supplmental file 1; Mustanski et al., 2014).

Comparisons were made between GENI participants and MYS participants who started the MYS at the ages of 12–14 and participated in the MYS for the first time between 2003–2011 (N = 3,370). There were no significant differences between the GENI sample and the MYS sample on gender, race, free or reduced school lunch, years in neighborhood, absence of mother or father figure, school suspension in the previous year, school expulsion in the previous year, arrest in previous year, thinking about killing self in the past year, attempt to kill self in past year, alcohol consumption in past 30 days, marijuana use in past year, sex in the past 90 days, or whether or not they have ever had sex (results not shown). The GENI sample was found to be older and more likely to come from a single female-headed household compared to the MYS sample (results not shown).

A propensity scoring methodology (D’Agostino, 1998) was used to calculate the likelihood of participants being in the treatment group based on similarities on a series of pre-move demographic variables and risk factors. The resulting propensity scores were entered into our models as a covariate to control for pre-move differences between the HOPE VI and control participants. We used the propensity score as a covariate instead of employing a matching technique in order to use the full sample in our analyses. This technique has been shown to reduce bias in estimated treatment effects (Berk & Newton, 1985; Berk, Newton, & Berk, 1986; Hirano, Imbens, & Ridder, 2003). The pre-move variables used to calculate the propensity score were: sex, child age, caregiver education level, caregiver marital status, time between move and GENI assessment (for control participants this was time between end of 2004 and GENI assessment), school enrollment, school lunch assistance, sexual risk-taking, drug use, conduct problems, and feelings about neighborhood. This analysis confirmed a central premise of our “natural experiment”—that youth in the two groups were similar on all pre-move demographic and risk factors (Supplemental File 1).

The availability and analysis of the pre-relocation census, demographic and risk factor data address the limitation of many housing relocation studies. Pre-relocation data allows for statistical control of between-group pre-relocation differences and within-subject pre-post relocation contrasts, so findings can be attributed to the move and not to other factors.

Statistical Analyses

Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) was used to test associations between neighborhood variables and risk outcomes in order to account for clustering of the data at three levels: person, family, and census tract at the time of the GENI interview. Initial analyses found that total variance between census tracts was small and non-significant for outcome variables and was therefore dropped to make subsequent models more parsimonious (results not shown; see Table 1 for ICCs). The intra-class correlations for outcome measures at the familial level, however, demonstrate the importance of accounting for clustering at that level. We took a step-by-step approach by entering variables in blocks in order to establish the effect of neighborhood relocation (HOPE VI status) and actual or perceived characteristics of the neighborhood that may explain such effects. As our independent variable of primary theoretical interest, block 1 included HOPE VI status along with sex, age and propensity score, which was included to control for any pre-relocation effects that could have confounded our estimation of neighborhood relocation effects. We tested interactions between HOPE VI status and both sex and age but did not include them in the models because, except for the sex and HOPE VI interaction for alcohol use, the interactions were not significant. In block 2, we added additional pre-relocation data, specifically the pre-move census characteristics to examine the effects of controlling for the more disadvantaged status of the HOPE VI neighborhood. To consider the effect of subjective experience of neighborhood characteristics, including neighborhood ecology, collective efficacy, and violence exposure, we included adolescent-reported neighborhood measures from the MYS and GENI interviews as well as caregiver-reported neighborhood measures from GENI in the third model. Research on neighborhoods show that both objective and subjective measures are essential and each explain unique variance and therefore we included them in separate blocks (Dhejne et al., 2011; Sampson & Raudenbush, 1997; Weden, Carpiano, & Robert, 2008; Weich, Holt, Twigg, Jones, & Lewis, 2003; Weich, Twigg, Holt, Lewis, & Jones, 2003; Weich, Twigg, Lewis, & Jones, 2005).

Table 1.

Means, SDs, and Intra-Class Correlations for Study Variables

| Measure and Constructs | Mean (SD) | Intra-class correlation (census tract) | Intra-class correlation (family) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood Scales- Adolescent Report | |||

| Neighborhood Ecology | 5.21 (3.75) | .159 | .432 |

| Collective Efficacy | 2.75 (.80) | .041 | .220 |

| Exposure to Violence | 1.75 (1.90) | .051 | .262 |

| Neighborhood Scales- Caregiver Report | |||

| Neighborhood Ecology | 3.14 (2.31) | .292 | – |

| Collective Efficacy | 2.78 (.86) | .202 | – |

| Exposure to Violence | 1.43 (1.52) | .136 | – |

| ARBA/H-RASP | |||

| Alcohol | .96 (2.92) | .037 | .210 |

| Marijuana | 2.96 (2.20) | .017 | .125 |

| Sex Risk | 1.67 (1.63) | .031 | .220 |

| C-DISC | |||

| MDD (% meeting criteria) | 3.7% | .083 | .313 |

| CD (% meeting criteria) | 7.7% | .029 | .165 |

| MDD Symptoms | 9.05 (7.27) | .058 | .333 |

| CD Symptoms | 11.46 (8.75) | .072 | .301 |

| YSR | |||

| Internalizing Scale | 4.50 (4.22) | .022 | .187 |

| Externalizing Scale | 3.01 (2.98) | .025 | .244 |

| CBCL | |||

| Internalizing Scale | 4.27 (4.89) | .060 | .597 |

| Externalizing Scale | 3.14 (2.63) | .069 | .381 |

Note: ARBA=AIDS Risk Behavior Assessment; H-RASP= HIV-Risk Assessment for Sexual Partnerships; C-DISC=Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children; MDD=Major Depressive Disorder; CD=Conduct Disorder; YSR=Youth Self Report; CBCL=Child Behavior Checklist.

Results

The demographic characteristics of the sample are provided in Table 2. Twenty percent of adolescents reported drinking at least once in the previous 12 months and 25.5% reported using marijuana. At the time of the GENI interview, participants lived within 64 different tracts with an average of 6.75 families per tract and an average of 1.36 children per family.

Table 2.

Participant Demographics (N=592 Adolescents)

| All | Control | HOPE VI | Comparison | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Variable | % (No.) | % (No.) | % (No.) | p-value |

| Adolescent Characteristics | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 48.8 (289) | 49.7 (243) | 43.9 (43) | NS |

| Female | 51.2 (303) | 50.3 (246) | 56.1 (55) | |

| African American | 98.8 (584) | 99.2 (483) | 96.9 (95) | NS |

| Age | ||||

| 13 | 1.7 (10) | 2.0 (10) | 0 | NS |

| 14 | 19.1 (113) | 21.3 (104) | 9.2 (9) | |

| 15 | 20.5 (121) | 21.1 (103) | 18.4 (18) | |

| 16 | 20.5 (121) | 18.4 (90) | 30.6 (30) | |

| 17 | 20.6 (122) | 18.6 (91) | 31.6 (31) | |

| 18 | 17.6 (104) | 18.6 (91) | 10.3 (10) | |

| Mean(sd) | 15.9 (1.4) | 15.9 (1.5) | 16.2 (1.1) | <.05 |

| School Attendance Status | NSa | |||

| Yes, regular school program | 80.5 (475) | 83.2 (405) | 66.3 (65) | |

| Yes, vocational/technical | 0.7 (4) | 0.6 (3) | 1.0 (1) | |

| Yes, special education | 0.2 (1) | 0.2 (1) | 0 | |

| Home schooling | 0.3 (2) | 0 | 2.0 (2) | |

| Not in school | 4.2 (25) | 2.7 (13) | 12.2 (12) | |

| Dropout | 3.7 (22) | 3.1 (15) | 7.1 (7) | |

| GED program | 4.9 (29) | 4.1 (20) | 9.2 (9) | |

| Graduated/completed school | 3.7 (22) | 4.1 (20) | 2.0 (2) | |

| Other | 1.7 (10) | 2.1 (10) | 0 | |

| Caregiver Characteristics | ||||

| Currently Working | ||||

| Yes | 40.4 (239) | 40.8 (199) | 40.8 (40) | NS |

| No | 59.6 (352) | 59.2 (289) | 59.2 (58) | |

| Educational Level | ||||

| Less than high school | 47.9 (283) | 49.1 (240) | 44.3 (43) | |

| High school graduate | 27.9 (165) | 25.6 (125) | 38.1 (37) | NS |

| Some college/specialized training | 18.8 (111) | 20.0 (98) | 11.3 (11) | |

| College graduate or higher | 5.4 (32) | 5.3 (26) | 6.2 (6) | |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 17.6 (104) | 16.6 (81) | 21.4 (21) | |

| Never married/no live-in partner | 53.9 (318) | 56.1 (273) | 42.9 (42) | NS |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 25.6 (151) | 24.6 (120) | 31.6 (31) | |

| Live-in partner | 2.9 (17) | 2.7 (13) | 4.1 (4) | |

| Amount Lived on Past Year | ||||

| <$10,000 | 50.7 (299) | 53.0 (259) | 21.4 (21) | |

| $10,000–$19,999 | 33.6 (198) | 32.7 (160) | 42.9 (42) | NSb |

| $20,000–$29,999 | 8.8 (52) | 8.0 (39) | 31.6 (31) | |

| $30,000 or more | 6.9 (41) | 6.3 (31) | 4.1 (4) | |

| Relationship to Child | ||||

| Biological mother | 74.5 (440) | 75.0 (366) | 70.4 (69) | |

| Other female | 16.9 (100) | 17.2 (84) | 16.3 (16) | NS |

| Any male | 8.6 (51) | 7.8 (38) | 13.2 (13) | |

for two groups: Yes, regular school program or graduated/completed school versus all others, p<.001

for two groups: <$20,000 versus $20,000 or more, p<.05

Table 3 presents the results of the regression models, which include (1) age, sex, HOPE VI status, and the propensity score; (2) model 1 plus pre-relocation census data; and (3) model 2 plus adolescent and caregiver reported neighborhood measures from MYS and GENI. There were no significant differences based on neighborhood relocation status for alcohol or marijuana use, sexual risk taking, or MDD symptoms in any of the models. There was a significant interaction for HOPE VI status by sex for alcohol use in model 1 only (β= 1.20, p<.05) such that HOPE VI boys had the highest frequency of alcohol use compared to boys in the control group and girls in either condition. Regarding C-DISC CD symptoms, HOPE VI (M=5.37(sd=4.14)) and control group (M=5.29(sd=3.87)) participants had a similar number of mean C-DISC CD symptoms (β= −0.16) although once pre-relocation census data (β= −1.46, p<.05) and neighborhood measures (β= −1.63, p<.01) were included in model 3, the difference became significant. For the YSR internalizing and externalizing scales and the CBCL externalizing scale, the differences based on relocation status became stronger with the addition of pre-move census data while there was little change based on inclusion of the subjective neighborhood measures (e.g., for the YSR internalizing scale, the β changed from −1.54 to −2.87 to −2.71). Adding pre-move census data to the model for the CBCL internalizing scale resulted in the significant difference (β= −1.79, p<.05) between the groups changing to non-significant.

Table 3.

Descriptives and Regression Models for the Effect of Neighborhood Relocation

| Measure: Outcome | HOPE VI Mean (SD) | Control Mean (SD) | Model 1: HOPE VI status, demographics, propensity score β (95% CI) | Model 2: Model 1 plus pre-relocation census data β (95% CI) | Model 3: Model 2 plus adolescent and caregiver neighborhood reports β (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARBA/H-RASP | |||||

| Alcohol | 1.20 (3.65) | .87 (2.60) | −0.27 (−0.81–.26) | −.48 (−1.42–.46) | −.50 (−1.55–.56) |

| Marijuana | 3.17 (2.23) | 2.85 (2.19) | −0.37 (−1.14–.40) | .01 (−1.57–1.60) | .67 (−1.27–2.64) |

| Sex Risk | 1.68 (1.60) | 1.67 (1.64) | −2.18 (−4.43–.07) | −2.90 (−6.40–.59) | −.37 (−0.87–.13) |

| C-DISC | |||||

| MDD Symptoms | 6.05 (4.98) | 5.67 (4.55) | −0.32 (−1.19–.55) | −0.95 (−2.37–.48) | −0.73 (−2.23–.76) |

| CD Symptoms | 5.37 (4.14) | 5.29 (3.87) | −0.16 (−.88–.57) | −1.46 (−2.62– −.30)* | −1.63 (−2.83– −.44)** |

| YSR | |||||

| Internalizing | 10.30 (8.00) | 8.61 (6.98) | −1.54 (−2.84– −.24)* | −2.87 (−4.98– −.75)** | −2.71 (−4.95– −.48)* |

| Externalizing | 13.59 (9.04) | 10.72 (8.53) | −2.77 (−4.38– −1.16)** | −5.59 (−8.24– −2.92)** | −5.59 (−8.18– −3.00)** |

| CBCL | |||||

| Internalizing | 8.63 (7.78) | 6.70 (6.99) | −1.79 (−3.15– −.44)* | −2.19 (−4.40– .01) | −1.82 (−4.14–.50) |

| Externalizing | 14.57 (13.10) | 11.39 (9.87) | −2.97 (−5.00– −.93)** | −4.86 (−8.24– −1.47)** | −4.43 (−8.09– −.78)* |

Note: ARBA=AIDS Risk Behavior Assessment; H-RASP= HIV-Risk Assessment for Sexual Partnerships; C-DISC=Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children; MDD=Major Depressive Disorder; CD=Conduct Disorder; YSR=Youth Self Report; CBCL=Child Behavior Checklist.

p<.05,

p<.01

Discussion

The intention of HOPE VI programs was to not only move public housing residents to better housing in safer neighborhoods, but also to improve residents’ quality of life (U.S. Senate, 2012). In our study, adolescents who relocated out of HOPE VI neighborhoods fared worse than control group participants on most self- and caregiver-reported mental health outcomes. In our first model, using only HOPE VI status, sex, age, and the propensity score, we examined whether relocating from the HOPE VI neighborhood affected outcomes. Model 2 accounted for the fact that, using objective census data, the HOPE VI neighborhood was worse than the control group neighborhoods. When we included this pre-relocation census data in our regression model, the negative effects were generally stronger than Model 1; therefore, if all participants were from equally high-poverty neighborhoods, the negative effect would have been even stronger. Including the subjective neighborhood characteristics in the third model did not substantively change the results after adding pre-move census data to the model.

Our findings generally suggest that moving from a high-poverty neighborhood to a slightly lower poverty neighborhood does not help adolescents achieve better mental and behavioral health outcomes; we know from previous analysis of this sample that the new neighborhoods, while better than the HOPE VI neighborhood, still had high rates of poverty (Mustanski et al., 2014; and Supplemental file 1). For the HOPE VI participants, the continued effects of having grown up in a high-poverty neighborhood (Sampson, 2008), the small improvements in their new neighborhoods, and/or the stress of moving (Hutton, Roberts, Walker, & Zuniga, 1987; Raviv, Keinan, Abazon, & Raviv, 1990) appears to make these youth worse off than the control group participants who consistently lived in the moderately disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Of note is the length of time that adolescents lived in their new neighborhoods. Participants had moved out of their HOPE VI neighborhood at least four years before their GENI interview, a significant amount of time in the context of adolescent development. We controlled for time since moving in the propensity scoring. However, it is possible that four years may not have been a long enough time to see changes in behavior and mental health outcomes, or at least not long enough to overcome the effects of growing up in higher poverty neighborhoods. It would be interesting to examine whether (1) relocation earlier in childhood would have resulted in different outcomes, and (2) longer-term follow up would show different mental health outcomes.

All housing relocation studies face the challenges of selection bias and finding families years after relocation, and GENI is no different. Our study also faced the limitations of “natural” experiments in that the research team did not control randomization and there may have been extraneous variables which impacted the results (Dunning, 2007). However, our analyses helped address these limitations by using pre-relocation data and propensity scores. A study limitation that was difficult to address is that while we included the time between the treatment group move and the GENI interview in the propensity score methodology, we do not have precise data on how long participants lived in various neighborhoods throughout their lives. The MTO analyses showed some changes in findings over time and perhaps we would see changes if we were to re-interview GENI participants at later dates.

Of note, the HOPE VI efforts in Mobile were complicated by the fact that the final relocation date (August 2005) coincided with the arrival of Hurricane Katrina, which strained the housing market due to hurricane-related damage as well as from people moving into Mobile from other cities that had even greater damage. As a result, many of the HOPE VI families moved to other public housing developments rather than private sector housing. Even so, these other public housing developments differ from one another on such factors as population density and rates of criminal and youth risk behaviors.

Because the self-reported MYS and GENI neighborhood data also do not explain the HOPE VI effect, further research is needed to understand why HOPE VI adolescents were exhibiting worse mental health outcomes. For example, the age at which the move occurred (Osypuk, Tchetgen, et al., 2012), family dynamics, changes in social support networks, the mental and physical health of parents/caregivers, and the quality and availability of mental health services in the community (Xue, Leventhal, Brooks-Gunn, & Earls, 2005) may have impacted the mental health outcomes of adolescents in our study. Future studies could include these factors to determine their importance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (RO1DA025039). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Gayle R. Byck, Department of Medical Social Sciences (MSS), Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University.

John Bolland, College of Human Environmental Sciences, University of Alabama.

Danielle Dick, Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics and Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Greg Swann, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University.

David Henry, Institute for Health Research and Policy, School of Public Health and Department of Psychology, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Brian S. Mustanski, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University.

References

- Achenbach T, Rescorla L. The manual for the aseba school-age forms & profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Sucoff CA. The neighborhood context of adolescent mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1996;37:293–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk RA, Newton PJ. Does arrest really deter wife battery? An effort to replicate the findings of the minneapolis spouse abuse experiment. Vol. 50. US: American Sociological Assn; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Berk RA, Newton PJ, Berk SF. What a difference a day makes: An empirical study of the impact of shelters for battered women. Vol. 48. US: National Council on Family Relations; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bolland JM. Overview of the mobile youth study. University of Alabama at Birmingham, School of Public Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X, Kim SY, Murry VM, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Conger RD. Neighborhood disadvantage moderates associations of parenting and older sibling problem attitudes and behavior with conduct disorders in african american children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:211–222. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Neighborhood context and racial differences in early adolescent sexual activity. Demography. 2004;41:697–720. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clampet-Lundquist S, Kling JR, Edin K, Duncan GJ. Moving teenagers out of high-risk neighborhoods: How girls fare better than boys. American Journal of Sociology. 2011;116:1154–1189. doi: 10.1086/657352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D, Spear S, Scribner R, Kissinger P, Mason K, Wildgen J. “Broken windows” and the risk of gonorrhea. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:230–236. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino RB. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Statistics in Medicine. 1998;17:2265–2281. doi: 10.1002/(Sici)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2265::Aid-Sim918>3.0.Co;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhejne C, Lichtenstein P, Boman M, Johansson ALV, Langstrom N, Landen M. Long-term follow-up of transsexual persons undergoing sex reassignment surgery: Cohort study in sweden. PLoS ONE. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016885. ArtID: e16885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling S, Johnson ME, Fisher DG. Reliability of drug users’ self-repor of recent drug use. Assessment. 1994;1:382–392. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning T. Improving causal inference: Strengths and limitations of natural experiments. Political Research Quarterly. 2007 doi: 10.1177/1065912907306470. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DuRant RH, Altman D, Wolfson M, Barkin S, Kreiter S, Krowchuk D. Exposure to violence and victimization, depression, substance use, and the use of violence by young adolescents. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2000;137:707–713. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.109146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuRant RH, Treiber F, Goodman E, Woods ER. Intentions to use violence among young adolescents. Pediatrics. 1996;98:1104–1108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennetian LA, Sciandra M, Sanbonmatsu L, Ludwig J, Katz LF, Duncan G, Kessler RC. The long-term impacts of moving to opportunity on youth outcomes. Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research. 2012;14:137–167. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan P. The role of exposure to community violence and developmental problems among inner-city youth. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:101–116. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001539. doi: doi:null. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, B Henry DB. A developmental-ecological model of the relation of family functioning to patterns of delinquency. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2000;16:169–198. [Google Scholar]

- Hirano K, Imbens GW, Ridder G. Efficient estimation of average treatment effects using the estimated propensity score. Econometrica. 2003;71:1161–1189. doi: 10.1111/1468-0262.00442. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton JB, Roberts TG, Walker J, Zuniga J. Ratings of severity of life events by ninth-grade students. Psychology in the Schools. 1987;24:63–68. doi: 10.1002/1520-6807(198701)24:1<63::AID-PITS2310240112>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IBS. Denver youth survey- youth interview schedule. University of Colorado; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Georgiades K, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Merikangas KR. Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of dsm-iv disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69 doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.160. archgenpsychiatry.2011.2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LA, Katz LF, Kling JR, Sampson NA, Ludwig J. Associations of housing mobility interventions for children inhigh-poverty neighborhoods with subsequent mental disorders during adolescence. JAMA. 2014;311:937–947. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Lang DL, Salazar LF, Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Brown LK, Donenberg GR. Neighborhood environment, sexual risk behaviors and acquisition of sexually transmitted infections among adolescents diagnosed with psychological disorders. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;46:303–311. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9352-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Moving to opportunity: An experimental study of neighborhood effects on mental health. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:1576–1582. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. A randomized study of neighborhood effects on low-income children’s educational outcomes. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:488–507. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.4.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Dupere V. Moving to opportunity: Does long-term exposure to ‘low-poverty’ neighborhoods make a difference for adolescents? Social Science and Medicine. 2011;73:737–743. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Dupere V, Brooks-Gunn J. Neighborhood influences on adolescent development. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 3rd. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2009. pp. 411–443. [Google Scholar]

- Morenoff JD, Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy, and the spatial dynamics of urban violence. Criminology. 2001;39:517–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2001.tb00932.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Byck G, Bolland J, Henry D, Swann G, Dick D. Patterns of neighborhood relocation in a longitudinal hope vi natuarl experiment: The genes, environment, and neighborhood initiative (geni) study. Institute for Policy Research Working Paper Series 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Starks TJ, Newcomb ME. Methods for the design and analysis of relationship and partner effects on sexual health. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0215-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebbitt VE, Lombe M, Sanders-Phillips K, Stokes C. Correlates of age at onset of sexual intercourse in african american adolescents living in urban public housing. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2010;21:1263–1277. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0936. doi: S1548686910400157 [pii] 10.1353/hpu.2010.0936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needle R, Fisher DG, Weatherby N, Chitwood D, Brown B, Cesari H, Braunstein M. Reliability of self-reported hiv risk behaviors of drug users. Psychology of Addictive Behavior. 1995;9:242–250. [Google Scholar]

- NIDA. Prevalence of drug use in the dc metropolitan area adult and juvenile offender populations: 1991. Rockville, MD: USDHHS; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nsuami MJ, Taylor SN, Smith BS, Martin DH. Increases in gonorrhea among high school students following hurricane katrina. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2009;85:194–198. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.031781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley D, Ruel E, Reid L. Atlanta’s last demolitions and relocations: The relationship between neighborhood characteristics and resident satisfaction. Housing Studies. 2013;28:205–234. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2013.767887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osypuk TL, Schmidt NM, Bates LM, Tchetgen-Tchetgen EJ, Earls FJ, Glymour MM. Gender and crime victimization modify neighborhood effects on adolescent mental health. Pediatrics. 2012;130:472–481. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osypuk TL, Tchetgen EJ, Acevedo-Garcia D, Earls FJ, Lincoln A, Schmidt NM, Glymour MM. Differential mental health effects of neighborhood relocation among youth in vulnerable families: Results from a randomized trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:1284–1294. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet S. Exposure to community violence: Defining the problem and understanding the consequences. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2000;9:7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Park N, Lee B, Bolland J, Vazsonyi A, Sun F. The Journal of Early Adolescence: SAGE. 2008. Early adolescent pathways of antisocial behaviors in poor, inner-city neighborhoods; pp. 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin SJ, Katz B, Cunningham MK, Brown KD, Gustafson J, Turner MA. A decade of hope vi: Research findings and policy challenges. The Urban Institute, The Brookings Institution; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin SJ, Leventhal T, Weismann G. Girls in the ’hood: Reframing safety and its impact on health and behavior. Urban Affairs Review. 2010;45:715–744. doi: 10.1177/1078087410361572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raviv A, Keinan G, Abazon Y, Raviv A. Moving as a stressful life event for adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology. 1990;18:130–140. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(199004)18:2<130::Aid-Jcop2290180205>3.0.Co;2-V. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JE, Popkin SJ. Employment and earnings of low-income blacks who move to middle-class suburbs. In: Jencks C, Peterson PE, editors. The urban underclass. Washington, DC: Brookings; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. Moving to inequality: Neighborhood effects and experiments meet social structure. American Journal of Sociology. 2008;114:189–231. doi: 10.1086/589843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing “neighborhood effects”: Social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology. 2002;28:443–478. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher PW, Lucas CP. The diagnostic interview schedule for children (disc) In: Henson M, editor. Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher PW, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. Nimh diagnostic interview schedule for children version iv (nimh disc-iv): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sucoff CA, Upchurch DM. Neighborhood context and the risk of adolescent childbearing among metropolitan-area black adolescents. American Sociological Review. 1998;63:571–585. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JC, Torrone EA, Browning CR. Neighborhood factors affecting rates of sexually transmitted diseases in chicago. Journal of Urban Health. 2010;87:102–112. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9410-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Senate. Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, Subcommittee on Housing, Transportation, and Community Development. Washington D.C.: U.S. Senate; 2012. Mar 27, Testimony of susan popkin, urban institute, prepared for the hearing on the choice neighborhoods initiative: A new community development model. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Voisin DR, Jenkins EJ, Takahashi L. Toward a conceptual model linking community violence exposure to hiv-related risk behaviors among adolescents: Directions for research. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;49:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watters JK. Street youth at risk for aids. Rockville, MD: USHHS, NIDA; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Weatherby NL, Needle R, Cesari H. Validity of self-reported drug use among injection drug users and crack cocaine users recruited through street outreach. Education Program Plan. 1994;17:347–355. [Google Scholar]

- Weden MM, Carpiano RM, Robert SA. Subjective and objective neighborhood characteristics and adult health. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:1256–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weich S, Holt G, Twigg L, Jones K, Lewis G. Geographic variation in the prevalence of common mental disorders in britain: A multilevel investigation. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;157:730–737. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weich S, Twigg L, Holt G, Lewis G, Jones K. Contextual risk factors for the common mental disorders in britain: A multilevel investigation of the effects of place. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57:616–621. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.8.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weich S, Twigg L, Lewis G, Jones K. Geographical variation in rates of common mental disorders in britain: Prospective cohort study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;187:29–34. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widome R, Sieving RE, Harpin SA, Hearst MO. Measuring neighborhood connection and the association with violence in young adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43:482–489. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J, Earls FJ. Neighborhood residence and mental health problems of 5- to 11-year-olds. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:554–563. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.