Abstract

Objectives:

To determine the epidemiological aspect of mucormycosis, the nature of malignancies complicated by mucormycosis, the initial site of involvement and the subsequent outcome.

Methods:

This was a cross-sectional study which was performed by reviewing the medical records of 95 patients with leukemia complicated with biopsy-proven mucormycosis admitted to the educational hospitals affiliated with Shiraz University of Medical Sciences over a 21-year period. We recorded demographic information including age and sex and disease characteristics such as type of leukemia, site of involvement, paraclinical findings at the time of admission and the outcome of the patients. The incidence of mucormycosis in leukemia was determined by identifying the number of leukemia patients diagnosed within the last 17 years.

Results:

The male to female ratio was 2.39:1 in of 95 patients studied. The overall incidence rate of mucormycosis was 4.27 per 100 leukemic patients in last 17 years which showed a decreasing trend from 2001 to 2011. The most frequent type of leukemia was acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) which was found in 58 patients (61.5%). The most common site of initial tumor involvement was sinonasal (90.16%). The mortality rate was about 54%, compared to the mortality rate of about 43.24% in patients with best prognosis of AML.

Conclusion:

The incidence of mucormycosis in leukemia showed a decreasing trend in our country and its recent incidence is comparable to that of other regions. The best preventive method against this lethal infection is to modify and control the environment which reduces the risk of exposure to air-born fungal spores.

Key Words: Mucormycosis, Leukemia, Iran

Introduction

Zygomycosis is an invasive fungal infection which is primarily caused by fungi belonging to the Mucoraceaefamily. As in other invasive fungal diseases, impairment of the immune system is the most important predisposing factor. Patients at risk usually have compromised defence mechanisms, mainly caused by diabetes mellitus, hematological diseases like leukemia or lymphoma, i.v. drug abuse or cytotoxic therapy.

Although there are reports of zygomycosis in otherwise healthy patients [1]. Mucormycosis is a rare invasive fungal infection seen most often in patients with haematological malignancies, particularly in the neutropenic phase [2]. After germination of the spores, the resulting hyphae proliferate and as the Mucorales have a particular predilection for blood vessels, angio-invasive disease is common, often leading to thrombosis and infarction of surrounding tissue. The type, extent and severity of the disease depend on the host defences and different risk factors [3]. In leukemia patients, zygomycosis usually leads to a delay or interruption of anti-leukemic therapy, thus increasing mortality not only through the fungal infection itself, but also from the inability to adequately treat the hematologic disease [1].

The diagnosis of zygomycosis is rarely suspected and antemortem diagnosis is made in only 23-50% of cases [4]. Early medical and surgical treatment could prevent further dissemination but some patients may be cured by surgical excision and amphotericin [5]. The association of this infection with haematological malignancies has not been adequately addressed in the literature. The aim of this retrospective study was to analyze the experience of our center about mucormycosis in haematologic malignancies. We conducted a 21-year retrospective review of all cases that hospitalized in 3 large Shiraz university hospitals as a referral center in southern Iran. The results were used to assess trends in the epidemiology of this infection, study the nature of malignancies complicated by mucormycosis, the initial site of involvement, the subsequent outcome of the victims and analyze their laboratory findings at the time of admission.

Materials and Methods

Study population

This was a retrospective cross-sectional study being performed in Nemazee, Shahid Faghihi and Khalili hospitals affiliated with Shiraz University hospitals, principal referral centers in southern Iran, over a period of 21 years from April 1990 through March 2011. We included all the patients who were pathologically diagnosed to have mucormycosis and leukemia who were admitted to our centers during the study period. We excluded those with underlying diseases other than leukemia including diabetes mellitus (DM). Of 162 mucormycosis cases 95 (58.6%) had leukemia as their underlying disease. The number of patients with leukemiain southern Iran was determined by the health centers during the past 17-year period from1995 to 2011. The study protocol was approved by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences institutional review board (IRB) and medical research ethics committee. As this was a retrospective analysis of medical charts, no informed written consents were obtained from the patients.

Study protocol

Evaluation at presentation included a detailed history, and otorhinolaryngologic, ophthalmic and neurologic examinations to assess the extent of the disease. Laboratory investigations included white blood cell count (WBC), hemoglobinlevel, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), blood sugar, serum bicarbonate and arterial PH. Diagnosis was made on histopathological examination and KOH preparation of biopsy specimens obtained from the nasal cavity and/or paranasal sinuses and the palate. An orbital fine needle aspiration cytological (FNAC) study was done in some patients when histopathological diagnosis from other sites was equivocal. Computerized tomographic scans of the paranasal sinuses, orbits and brain were obtained to assess the extent of disease. All these information were obtained from the medical charts by reviewing and entering into a standard data gathering form.

The treatment strategies were similar in all the patients. All the patients were treated with systemic Amphotericin B as soon as the diagnosis of mucor was established, along with treatment to stabilize the underlying metabolic derangement. After a test dose of 1 mg of amphotericin B in 100 ml of normal saline, 0.7 mg/kg/day of amphotericin B was given over 6 hours. All the patients underwent local resection of the lesions until a safe margin was reached. The outcome of treatment group was evaluated in terms of treatment success and treatment failure. Treatment success was defined as a disease-free, stable patient with controlled metabolic status. Treatment failure was defined as progression of disease to a more advanced stage, worsening general condition or mortality due to the infection. We also recorded epidemiological characteristics, the site of infection and type of leukemia and its duration and characteristics.

Statistical analysis

The statistical package for social science, SPSS for Windows, Version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis. Data are reported as mean ± SD and proportions as appropriate. A p-value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

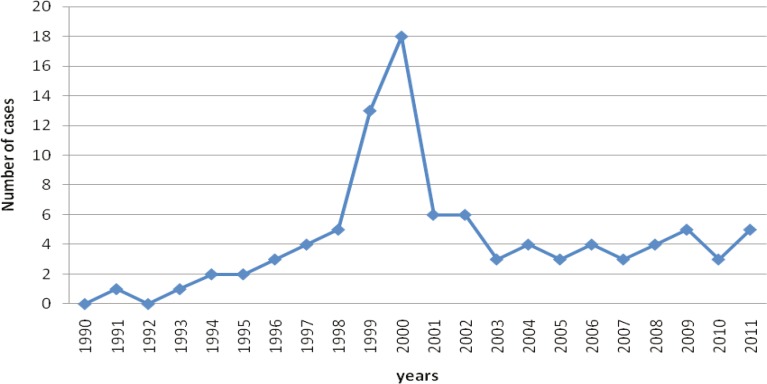

A review of hospital records identified 162 cases of mucormycosis admitted to Shiraz University hospitals, during the last 21 years from April 1990 through March 2011, of which 95 (58.6%) patients had leukemias their underlying disease of which 67 (70.5%) were males and 28(29.5%) were females(Male to Female ratio: 2.39:1). The age of patients with leukemia and mucormycosis ranged from 6 to 80 years with mean of 30.08±16.25 years. Figure 1 shows the number of mucormycotic leukemia patients admitted tour departments during the study period.

Fig. 1.

The number of leukemia patients with mucormycosisadmitted toShirazUniversity hospitals from 1990 to 2011

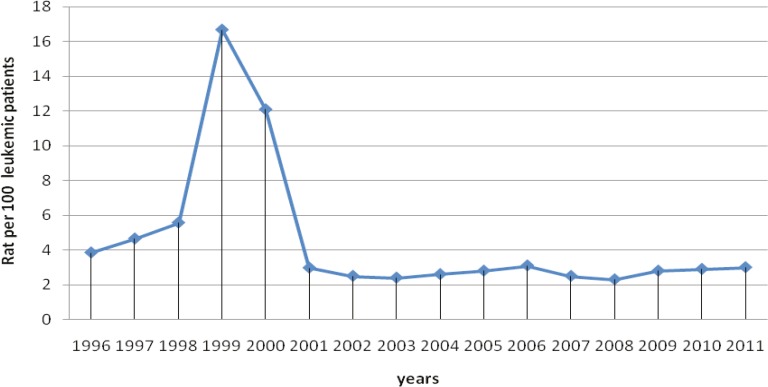

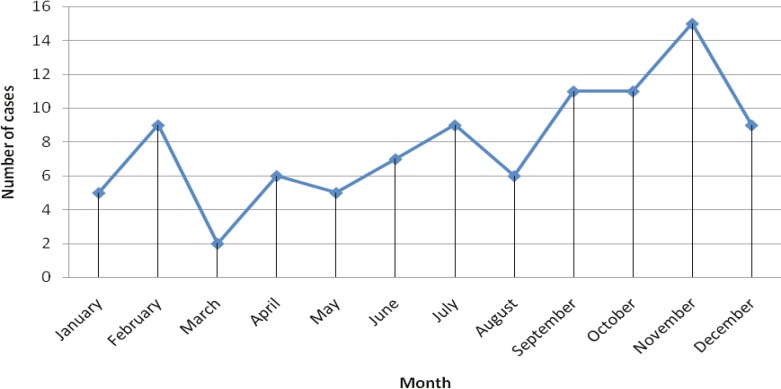

The number of patients increased significantly in years 1999 and 2000. The annual incidence rate of mucormycosis in leukemia patients during the last 17 years was found to be significantly higher (p<0.001) in 1999 and 2000 compared to other years (Figure 2). An overall incidence rate of mucormycosis was 4.27 per 100 leukemia patients in a 17-year period from 1996 to 2011. Distribution of mucormycotic leukemia patients according to the month of onset is shown in Figure 3, without noticeable seasonal pattern (p=0.125).The most frequent type of leukemia was acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) that was found in 58 (61.5%) patients followed by acute lymphogenous leukemia (ALL) in 25 (26.3%), chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) in 6 (6.3%), chronic lymphogenous leukemia (CLL) in 2 (2.1%), biphenotypic leukemia in 1 (1.06%), hairy cell leukemia in 1 (1.06%) and unknown types of leukemia in 2 (2.1%) patients.

Fig. 2.

Annual incidence rates of mucormycosis in leukemic patients in southern Iranfrom1996 to 2011.

Fig. 3.

The number of mucormycoticleukemic patients admitted to Shiraz University hospitals based on the month of onset from1990 to 2011

The initial site of involvement in 83 (88.6%) patients was sinus, nose or both, and in 2 (2.1%) case shard palate was involved. The tonsils, lung, vagina, and arm skin were affected in1 (1.06%) patient each. The laboratory findings of the patients are summarized in Table 1. We found that 50 (52.6%) patients had WBC count lower than 3.5×103/μlit while in 30 (31.57%) patients WBC count was more than 10×103/μlit. Hemoglobin level in 20 (21.3%) cases was lower than 7gr/dlit, in 60 (65.58%) was between 7 and 10 gr/ dlit and in 15 (14.73%) higher than 10gr/dlit. Serum pH in 28 (29.47%) cases was higher than 7.45 while in 3 (3.15%) patients it was lower than 7.35. Serum bicarbonate was higher than 24mg/dlit in 9 (9.47%) and lower than15 mg/dlit. in 6 (6.31%) patients.

Table 1.

Laboratory findings of leukemiamucormycotic patients in southern Iranfrom1990 to2011.

| Laboratory test (measure unit) | Min | Max | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cell count (103/μlit) | 0.1 | 228.3 | 19.26 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dlit) | 5 | 101 | 19.18 |

| Hemoglobin level (gr/dlit) | 4 | 13 | 8.05 |

| Fasting blood sugar (mg/dlit) | 55 | 433 | 140.77 |

| Serum PH | 7.22 | 7.57 | 7.43 |

| Serum bicarbonate (meq/lit) | 6.5 | 31.6 | 21.37 |

A total number of 54(56.8%) patients died of which 43% had AML with mucormycosis. About 75% had ALL with mucormycosis and 75% had CML with mucormycosis. Other fatalities included one patient with CLL and one case with unknown type of leukemia.

Our analysis showed that the patients’ age, sex and laboratory findings had no effects on the prognosis of these patients. All patients received medical treatment with amphotericin B early after suspicious diagnosis with mucormycosis, while 87 (91.5%) them also underwent surgical intervention. The time lag between onsets of symptoms referable to zygomycosis and starting amphotericin B administration ranged from 3 to 85 days with a median of 9 days. The antifungal dose ranged from 0 to 3300 mg with median 1000 mg and duration of treatment being 35 days which ranged from1 to 92 days. The median time lag between onset of symptoms and surgical management was 12 days with a range varying from 7 to 45 days.

Discussion

Invasive fungal infections caused by yeasts and moulds are frequent problems in hematologic patients [1]. Zygomycosis is the third most common invasive fungal infection next to candidias is and aspergillosis that accounts for 8.3-13% of all fungal infections discovered at post mortem in patients with hematologic disorders [4]. This is evidenced by an increase in zygomycosis from 8 to 20 per 100,000 admissions between 1989 to1993 and 1994to1998. However in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients the rate was 10/4020 (0.25%) [6]. Three independent publications reported rates of 8.9%, 3.2% and 4.3% in HSCT patients, all attributed the sharp rise in voriconazoleuse in late 2002 [7-9]. In our study, a significant increase was found in the number of patients with haematologic malignancies superimposed by mucormycosis in 1999 and 2000. All our patients were diagnosed before death, and overall the incidence rate of mucormycosis in leukemic patients was 4.27 per 100.Considering the patients with undiagnosed mucormycosis before death, the virtual incidence rate of mucormycosis in leukemic patients in our country might be higher than other regions. But the annual incidence rate of mucormycosis was not the same. The highest incidence rate was seen in 1999 followed by a decreasing trend in ensuing decade. Following increase in the incidence of mucormycosis in 1999, attempts were made to control and modify the conditions in haematological wards to reduce the risk of exposure to air-born spores. These included excluding flowers and live plants from these wards, continuous isolation of such neutropenic patients who are at higher risk for these fungal infections, wearing masks and monitoring of air quality and condition. The incidence of mucormycosis was then significantly decreased by taking such measures and conducting appropriate interventions so that it became consistent with that of developed countries in subsequent decade.

The association of type of leukemia and mucormycosis has not been adequately addressed in the literature but in our study the most common neoplasm complicated by this fungal infection was AML followed by ALL.

Various studies yielded different results about the influence of age and sex on mucormycosis. Bitaret et al. believed that strict comparison of age distributions was not possible in different studies [10]. But it seems that sex is an important predisposing factor for mucormycosis. In a recent study conducted by Jagarlamundi et al. it was shown that all patients with acute leukemia and mucormycosis the male sex was dominant (M:F=2.5:1) where they age of patients ranged from 6 to 66 ( mean age 36 years) [11]. In our study, themselves were also dominant (M:F=2.38:1) and the patients aged from 6 to 80 ( mean age 30.08 years). Considering that diabetic female patients were older (mean age 61 years) and acquire infections more often than males [12]. It seems that gender and age distributions confer most important impact on underlying diseases in patients with mucormycosis where diabetics are older females and leukemia involve younger male patients. Rhinocerebralzygomycosis is the most common presentation and almost always associated with hyper glycemia and metabolic acidosis [13]. It is reported to be the most frequent form of mucormycosis in several studies [14-16]. Patients with leukemia have traditionally been considered to represent the majority of cases with pulmonary mucormycosis [16] and in some studies pulmonary mucormycosis is the most prevalent form in patients with leukemia [2]. A retrospective study by Pagano et al. identified 59 patients with haematological malignancy and mucormycosis. The most common presentation was pulmonary mucor, which accounted for 64% of cases of which 24%, involved orbital and maxillofacial areas [2]. The majority of our cases presented with rhinocerebral mucormycosis and only one patient had pleural involvement.

The main cause of this infection is probably the prolonged and profound neutropenia secondary to the myeloablative treatments for the underlying hematologic malignancy [2]. The importance of neutropenia as a contributing factor to infection in patients with hematologic malignancies has already been demonstrated [2].Consistent with other studies we found that majority of our cases had neutropenia or leukocytosis which supports that neutrophil dysfunction is the major risk factor for developing fungal infections in haematologic malignancies. Several researches show a preponderance of infections in patients with low hemoglobin levels and anemia such as thalassemia or aplastic anemia as predisposing factors for mucormycosis [17-19] which is inversely proportional to the extent of the disease. Nearly all of our patients were anemic at the time of acquiring infection.

The widespread use of steroids had also resulted in an increased incidence of zygomycosis in this population of patients who had chronically or acutely been treated with this class of drugs [19-21]. The mechanism by which the corticosteroids enhance susceptibility to zygomycosis is probably two fold. First, steroids suppress the normal inflammatory cell response and second they may induce a diabetic state [19-21].

Invasive zygomycosis is simply dismal news for patients as well as treating physicians. Indeed, despite recent medical advances, this aggressive fungal infection still carries poor prognosis. Since deep mucormycosis encompasses many syndromes, the mortality rate varies greatly from 33.3% in a Korean study [22] to a worse rate of 63% in an Italian report [2] to a staggering 96% rate in regard to disseminated form [13]. This extreme variation in mucormycosis mortality rate can be explained by many factors, including early diagnosis, site of the infection, patient's immune status, correction of other co- morbid factors, and among others the type of therapy instituted. In our study all patients were treated with amphotericin B and deoxycholate. Lipid soluble form of amphotericin B was not used because of its higher cost and lack of availability. Only 8 patients did not undergo surgical treatment and patients with more surgical interventions had better outcome. The overall 56.8% mortality rate was reported in our study which was consistent with other reports [12-14]. Mucormycosis occurred in all of our patients after receiving chemotherapy that had corticosteroids in their chemotherapy protocol. It seems that about 44% of our patients were in diabetic state without any history of diabetes before developing leukemia. Because mucormycosis is a highly lethal infection with mortality rates of 50% or more and despite aggressive management even in the best medical centers, the prevention and lowering the incidence of this infection is a priority for immune-compromised patients such as those with malignancies (especially hematologic), diabetic ketoacidosis and AIDS, who seem to be at higher risk for this infection. Considering that the most common method of transmission of this infection is via inhalation of spores that are mainly present in the soil, air, atmosphere of hospital wards and decaying materials, taking appropriate measures to control and modify the environment that reduce the risk of exposure to fungal spores seems to be the best preventive approach for this lethal infection.

Acknowledgment

We appreciate kind cooperation of surgery and internal departments and medical archives of Nemazee, Shahid Faghihi and Khalili hospitals of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Lerchenmüller C, Göner M, Büchner T, Berdel WE. Rhinocerebralzygomycosis in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Ann Oncol. 2001;12(3):415–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1011119018112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pagano L, Offidani M, Fianchi L, Nosari A, Candoni A, Piccardi M, et al. Mucormycosis in hematologic patients. Haematologica. 2004;89(2):207–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barr A, Nolan M, Grant W, Costello C, Petrou MA. Rhinoorbital and pulmonary zygomycosis post pulmonary aspergilloma in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Acta Biomed. 2006;77 (Suppl 4):13–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nosari A, Oreste P, Montillo M, Carrafiello G, Draisci M, Muti G, et al. Mucormycosis in hematologic malignancies: an emerging fungal infection. Haematologica. 2000;85(10):1068–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prabhu RM, Patel R. Mucormycosis and entomophthoramycosis: a review of the clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;( Suppl 1):10–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-9465.2004.00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kontoyiannis DP, Wessel VC, Bodey GP, Rolston KV. Zygomycosis in the 1990s in a tertiary-care cancer centre. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(6):851–6. doi: 10.1086/313803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siwek GT, Dodgson KJ, de Magalhaes-Silverman M, Bartelt LA, Kilborn SB, Hoth PL, et al. Invasive zygomycosis in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients receiving voriconazole prophylaxis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(4):584–7. doi: 10.1086/422723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marty FM, Cosimi LA, Baden LR. Breakthrough zygomycosis after voriconazole treatment in recipients of hematopoietic stem-cell transplants. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(9):950–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200402263500923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imhof A, Balajee SA, Fredricks DN, Englund JA, Marr KA. Breakthrough fungal infections in stem cell transplant recipients receiving voriconazole. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(5):743–6. doi: 10.1086/423274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bitar D, Van Cauteren D, Lanternier F, Dannaoui E, Che D, Dromer F, et al. Increasing incidence of zygomycosis (mucormycosis), France, 1997-2006. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(9):1395–401. doi: 10.3201/eid1509.090334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jagarlamudi R, Kumar L, Kochupillai V, Kapil A, Banerjee U, Thulkar S. Infections in acute leukemia: an analysis of 240 febrile episodes. Med Oncol. 2000;17(2):111–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02796205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertoni AG, Saydah S, Brancati FL. Diabetes and the risk of infection-related mortality in the U S. . Diabetes Care. 2001;24(6):1044–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, Knudsen TA, Sarkisova TA, Schaufele RL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(5):634–53. doi: 10.1086/432579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martín-Moro JG, Calleja JM, García MB, Carretero JL, Rodríguez JG. Rhinoorbitocerebral mucormycosis: a case report and literature review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13(12):E792–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meis JF, Chakrabarti A. Changing epidemiology of an emerging infection: zygomycosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;( Suppl 5):15–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chakrabrati A, Das A, Sharma A, Panda N, Das S, Gupta KL, et al. Ten years’ experience in zygomycosis at a tertiary care center in India. Journal of Infection. 2001;42(4):261–6. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2001.0831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grant JM, St-Germain G, McDonald JC. Successful treatment of invasive Rhizopus infection in a child with thalassemia. Med Mycol. 2006;44(8):771–5. doi: 10.1080/13693780600930186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma R, Shivanand G, Kumar R, Prem S, Kandpal H, Das CJ, et al. Isolated renal mucormycosis: An unusual cause of acute renal infarction in a boy with aplastic anaemia. Br J Radiol. 2006;79(943):e19–21. doi: 10.1259/bjr/17821080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gadadhar H, Hawkins S, Huffstutter JE, Panda M. Cutaneous mucormycosis complicating methotrexate, prednisone, and infliximab therapy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2007;13(6):361–2. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31815d3ddd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Devlin SM, Hu B, Ippoliti A. Mucormycosis presenting as recurrent gastric perforation in a patient with Crohn's disease on glucocorticoid, 6-mercaptopurine, and infliximab therapy. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52(9):2078–81. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9455-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferguson AD. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis acquired after a short course of prednisone therapy. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2007;107(11):491–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung SH, Kim SW, Park CS, Song CE, Cho JH, Lee JH, et al. Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis: consideration of prognostic factors and treatment modality. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2009;36(3):274–9. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]