Abstract

Mycoplasma genitalium, a human pathogen associated with sexually transmitted diseases, is capable of causing chronic infections, though mechanisms for persistence remain unclear. Previous studies have found that variation of the MgPa operon occurs by recombination of repetitive chromosomal sequences (known as MgPars) into the MG191 and MG192 genes carried on this operon, which may lead to antigenic variation and immune evasion. In this study, we determined the kinetics of MG192 sequence variation during the course of experimental infection using archived specimens from two chimpanzees infected with M. genitalium strain G37. The highly variable region of MG192 was amplified by PCR from M. genitalium isolates obtained at various time points postinfection (p.i.). Sequence analysis revealed that MG192 sequence variation began at 5 weeks p.i. With the progression of infection, sequence changes accumulated throughout the MG192 variable region. The presence of MG192 variants at specific time points was confirmed by variant-specific PCR assays and sequence analysis of single-colony cloned M. genitalium organisms. MG192 nucleotide sequence variation correlated with estimated recombination events, predicted amino acid changes, and time of seroconversion, a finding consistent with immune selection of MG192 variants. In addition, we provided evidence that MG192 sequence variation occurred during the process of M. genitalium single-colony cloning. Such spontaneous variation suggests that some MG192 variation is independent of immune selection but may form the basis for subsequent immune selection.

INTRODUCTION

Mycoplasma genitalium is an important etiology of urogenital tract infections in humans and can be transmitted heterosexually or homosexually. Like infections caused by other pathogenic mycoplasmas, M. genitalium infections can persist for several months to more than 2 years as has been documented in animal models (1, 2) and humans (3–5). One of the best-known potential mechanisms for persistence is antigenic variation of two immunodominant surface proteins encoded by the MG191 (mgpB or P140) and MG192 (mgpC or P110) genes in the M. genitalium MgPa operon (5–11).

Genetic variation in the MG191 and MG192 genes was first described in 1995 by Peterson et al. (11), but it was not until 2007 that we (10) and others (7) confirmed that this variation resulted from the recombination of the MG191 and MG192 variable regions with chromosomal repeats outside the MgPa operon, known as MgPa repeats or MgPar sequences. While the functional consequences of genetic variation at MG191 and MG192 remain unclear, it has been hypothesized that genetic variation can either change the antigenicity of the proteins to allow immune evasion or alter the mobility and adhesion ability of the organism to adapt to diverse host microenvironments, thus facilitating persistent infection (5–13). The former hypothesis is supported by a recent study in a pig-tailed macaque model in which MG191 sequence changes lead to reduced reactivity to antibodies produced at the early stage (13). There has been no proof yet of linkage between MG192 sequence variations and antigenic changes.

Previous studies of M. genitalium clinical specimens by us (5, 9, 10) and others (6, 7) have detected mixed populations of organisms with highly heterogeneous MG191 and MG192 sequences in almost all specimens examined, which makes it difficult to determine the founder sequence and its evolution during the course of chronic infection. In this study, we took advantage of the availability of archived M. genitalium isolates obtained in the course of infection in chimpanzees inoculated with a single cloned M. genitalium population (2). The primary goal of this study was to investigate the kinetics of MG192 sequence variation during the course of experimental M. genitalium infection in chimpanzees.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

M. genitalium specimens.

A complete collection of eight primary specimens (urethral swabs) from two male chimpanzees inoculated intraurethrally with cloned M. genitalium type strain G37 was kindly provided by J. Tully, NIAID, Bethesda, Maryland. Details of the animal model were described elsewhere (2). Four swabs from each of two animals (identified as no. A52 and no. 1125) were obtained at different time points during a course of 13 weeks postinoculation (p.i.). The first swab specimen was obtained immediately after intraurethral inoculation (0 week p.i.). Urethral swabs were collected in SP4 medium, and after the initial culture studies, remnants of the urethral swabs were stored at −80°C. The urethral swab specimens were shipped on dry ice to Copenhagen, Denmark, where isolation was performed in Friis's modified broth medium (14). Initial sequence analysis of the MG191 repeated B region in the swab isolate from chimpanzee no. 1125 at 11 weeks p.i. revealed mixed sequences (J. S. Jensen, unpublished observations), and therefore, this isolate was subjected to in vitro mycoplasma single-colony cloning (here referred to as MSCC) using a filtration procedure as described elsewhere (14). A total of 20 MSCC clones were obtained. The study protocol was approved by the LSUHSC Institutional Review Board.

PCR and sequence analysis of the MG192 gene.

All eight urethral swab isolates and 20 MSCC clones were used for PCR and sequence analysis. Genomic DNA was extracted using the Chelex 100 Resin (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) as described elsewhere (15). The whole MG192 variable region in each isolate was amplified by PCR with a pair of primers, MG192A (5′-CACTAGCCAATACCTTCCTTGTCAAAGAGG-3′) and 227529R (5′-GATCTGATCAGTTCTGGAAGGTAAACG-3′), as described elsewhere (10, 16). Both primers were located in the flanking, conserved region of the MG192 gene (with no homology to any MgPars), so that only the MG192 gene but not MgPars would be amplified. The PCR products were sequenced directly (without cloning into plasmid vectors, here referred to as direct sequencing) and/or after cloning into plasmid vectors using the TOPO TA Cloning kit (Invitrogen) as described elsewhere (9, 10) (here referred to as plasmid cloning). A sequence “variant” refers to a unique sequence present in one or more plasmid clones obtained from the same isolate studied. Each variant is designated by a number representing the time point in weeks postinfection, followed by a letter for a unique variant sequence (uppercase for chimpanzee no. A52 and lowercase for chimpanzee no. 1125). Possible recombination events in each variant were determined by comparing the MG192 sequences to G37 MgPars (9, 10). A single recombination event was defined as a segmental sequence change in the MG192 variable region that matches a segment of any G37 MgPars 100%, excluding variation in the copy number of the AGT trinucleotide repeat.

Confirmation of MG192 variants by variant-specific PCR.

To verify the presence of MG192 variants specific for a given time point, variant-specific primers were designed to amplify selected specific MG192 variant sequences. The primers included 5wf, 5′-TCCAGTGAAAAAAGATGAAGC-3′, for MG192 variant 5f; 9wr, 5′-AAGGGAGGTGCATCTC-3′, for variant 9i; 11wr, 5′-GCCACTTGAACTATATGTA-3′, for variant 11j; and k20f, 5′-GACATGAACCAAGTACTGAAAA-3′, for variant 11n. For each selected MG192 variant, PCR was performed on genomic DNA extracted from urethral swab isolates using one variant-specific primer paired with either primer 192A or 227529R as described above. Reaction mixture volumes were 50 μl, containing 50 ng DNA, 0.5 μM each primer, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 100 μM (each) dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP, and 1 U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems). Thermal cycling parameters were as follows: 94°C hot start for 9 min, 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. Amplicons were examined on 1.2% agarose gels.

Genotyping of M. genitalium isolates by MG191-single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis.

PCR and sequencing of the MG191 conserved region AB (approximately 280 bp) were performed as we described previously (3, 17).

Possibility of DNA recombination between MG192 variants or between MG192 and MgPars during PCR.

To test if DNA recombination occurred during PCR between MG192 sequences or between MG192 and MgPars, we did spiking experiments by mixing two plasmids containing different MG192 sequences (with 13% of nucleotides different) or mixing one plasmid containing an MG192 sequence (MG192 variant of M2282) with another plasmid containing an MgPar sequence (G37 MgPar 9) and then reamplifying using MG192 primers 5360F (9) and 227567R (10). The amplicons were cloned into TOPO plasmid vector. Ten plasmid clones were sequenced for the PCR amplicon from the mixture of two MG192 plasmids, and 12 clones were sequenced for the PCR amplicon from the mixture of one MG192 plasmid and one MgPar plasmid.

Bioinformatics analyses.

Sequence analysis was done using the CLC Combined Workbench 1.0.2 (CLC bio, Aarhus, Denmark). Phylogeny analysis was performed by using MAFFT version 6 (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server). All statistic tests were carried out using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The correlation of the change in nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequences and recombination events with the progression of the infection was assessed by Spearman's correlation test.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The MG192 sequences described in this study have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers JX869102 to JX869132.

RESULTS

PCR and sequence analysis of MG192 variable regions.

We analyzed a total of eight urethral swab isolates from two infected chimpanzees with one isolate from each of the four time points studied (Table 1) and an additional 20 MSCC clones from the 11-week swab isolate in one of these two animals (Table 2). By direct sequencing of the MG192 PCR products, all eight swab isolates showed mixed sequences except for the 0-week isolate from both chimpanzees and the 9-week isolate from the chimpanzee no. 1125, which showed homogeneous sequences. After cloning PCR products from all isolates into plasmids, we sequenced 5 to 15 plasmid clones for each isolate, which yielded 1 to 8 unique MG192 sequences (referred to as MG192 variants) for each isolate (Table 1 and Fig. 1). The single parental sequence in the 0-week isolate and one variant from the 5-week isolate of both animals were identical to the MG192 sequence of the published G37 genome sequence (18), designated G37T, whereas all remaining variants were different from each other and from the G37T sequence. The detection of a single MG192 sequence at week 0 is expected, since the isolate for this time point represents the inoculum, which was obtained by three rounds of in vitro MSCC cloning (2).

TABLE 1.

MG192 variant sequences of M. genitalium isolates from two chimpanzees infected with strain G37T

| Animal no. and no. of wk p.i. | No. of unique sequences/total no. of plasmid or MSCC clones analyzeda | Avg no. ± SD (%) of: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recombination events relative to G37T MgPars | Nucleotide changes relative to G37Tb | Deduced amino acid changes relative to G37Tb | ||

| Animal no. A52 | ||||

| 0 | 1/5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 4/8 | 0.75 ± 0.5 | 31.5 ± 34.4 (2.2) | 12.8 ± 9.6 (2.7) |

| 10 | 8/10 | 5.6 ± 0.7 | 130.8 ± 17.5 (9.2) | 46.1 ± 5.2 (9.7) |

| 13 | 3/8 | 3 ± 0 | 111.7 ± 5.8 (7.8) | 34 ± 2.6 (7.2) |

| Spearman's testc | 0.519 (P < 0.040) | 0.573 (P < 0.020) | 0.502 (P < 0.047) | |

| Animal no. 1125 | ||||

| 0 | 1/10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 8/15 | 2.3 ± 1.3 | 38.9 ± 20.5 (2.7) | 14.5 ± 7.5 (3.1) |

| 9 | 1/15 | 3 | 130 (9.1) | 48 (10.1) |

| 11 | 4/29d | 7.6 ± 1.5 | 117.9 ± 13.3 (8.3) | 40 ± 7.3 (8.4) |

| Spearman's testc | 0.883 (P < 0.0001) | 0.841 (P < 0.0001) | 0.841 (P < 0.0001) | |

All clones are plasmid clones except for the 29 clones at 11 weeks p.i. from animal no. 1125 as explained below in footnote d.

Compared to the published G37T MG192 variable region (1,423 nucleotides or 474 amino acids). Changes include base substitutions, deletions, and insertions in regions flanking the AGT triplet repeat region. Values are averages ± standard deviations for more than one variant.

Spearman's rank correlation coefficient.

Including variants 11j, 11k, 11l, and 11m from 17 MSCC clones and 12 plasmid clones derived from other three MSCC clones. The 12 plasmid clones are included here, since four variants identified from them were also found in the uncloned swab isolate. From the same three MSCC clones above, we obtained an additional seven plasmid clones, which contained three unique sequences (variants 11n, 11o, and 11p); they are not included in this table because they were not detected in the uncloned swab isolate and might have been introduced in vitro during the MSCC process. See Table 2 for more details.

TABLE 2.

MG192 variant sequences identified in 20 M. genitalium MSCC clones from the 11-week swab isolate from chimpanzee no. 1125

| No. of MSCC clones (clone designation) | MG192 variant by direct sequencing | No. of plasmid clones | MG192 variant from plasmid clones |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 11ja | NAc | NA |

| 11 | 11ka | NA | NA |

| 1 (K4) | Mixture | 4 | 11ja |

| 2 | 11 ma | ||

| 1 (K13) | Mixture | 2 | 11ja |

| 2 | 11ka | ||

| 1 | 11la | ||

| 1 (K20) | Mixture | 1 | 11ja |

| 5 | 11nb | ||

| 1 | 11ob | ||

| 1 | 11pb |

Also found in the uncloned swab isolate by sequencing of cloned PCR products or variant-specific PCR.

Not detected in the uncloned swab isolate by variant-specific PCR and thus excluded for analysis shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1.

NA, not cloned into plasmid since direct sequencing showed clear, homogeneous sequences.

FIG 1.

Progressive MG192 sequence variation during the course of M. genitalium infection in two chimpanzees experimentally infected with strain G37T. The labels below the x axis represent variant sequences identified at various time points as explained in detail in Materials and Methods.

Of the 20 MSCC clones obtained from the swab isolate at 11 weeks p.i. from chimpanzee no. 1125, 17 clones fell into two distinct populations (MG192 variants 11j and 11k) based on the results of direct sequencing (in which there was no indication of mixed sequences), and the remaining 3 MSCC clones showed mixed sequences. In subsequent plasmid cloning and sequence analysis, two to four MG192 variant sequences were found for each of these three MSCC clones (Table 2). Sequencing of nine plasmid inserts derived from the PCR product directly amplified from the 11-week swab isolate (uncloned mycoplasma culture) yielded two distinct MG192 variants, which were identical to the two major MG192 variant sequences 11j and 11k, respectively, found from the 17 MSCC clones.

The nucleotide sequence changes described above included substitutions, insertions, and/or deletions, none of which resulted in reading frame shifts or stop codons in the predicted open reading frame. The majority (∼75%) of the nucleotide changes led to deduced amino acid changes (up to 10% difference in the entire MG192 variable region compared to G37T). All nucleotide changes could be traced to a specific MgPar donor sequence of G37T, except that a single substitution from T to C at the same position was present in two MG192 variants (10E and 10I) in the 10-week isolate from animal A52. Figure 2 shows several examples of MG192 sequence changes and their relationship with G37T MgPars.

FIG 2.

Schematic diagram of representative MG192 variant sequences identified in M. genitalium isolates from a chimpanzee (no. 1125) experimentally infected with strain G37T. Various patterns in MG192 variants represent regions that are different from the G37T MG192 sequence and instead have homology to G37T MgPars, as indicated by the different patterns. Names and approximate locations of primers used in variant-specific PCR are indicated by arrows. See Materials and Methods for variant designations.

Kinetic analysis of MG192 variation during the course of infection in chimpanzees.

MG192 sequence variation was detected at 5 weeks p.i. and through the end of the experiment in both animals. The parental G37 MG192 sequence was present only as a small population at 5 weeks p.i. (variant 5A in chimpanzee no. A52 and variant 5a in chimpanzee no. 1125) (Fig. 1) and absent at all subsequent time points. All other variant sequences were specific for different time points, and none of them was shared between any two time points in each animal or between two animals. The time point of detection of sequence changes was consistent with that of seroconversion time as previously reported for both animals (2), i.e., chimpanzee 1125 seroconverted between 5 and 6 weeks p.i., and chimpanzee A52 seroconverted between 4 and 5 weeks p.i. Quantitative assessment of nucleotide and predicted amino acid changes revealed progressive increases in MG192 sequence variation over time in the course of infection in both animals as shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1 (Spearman's test, P < 0.05 for all). These changes correlated well with the estimated number of recombination events (Table 1).

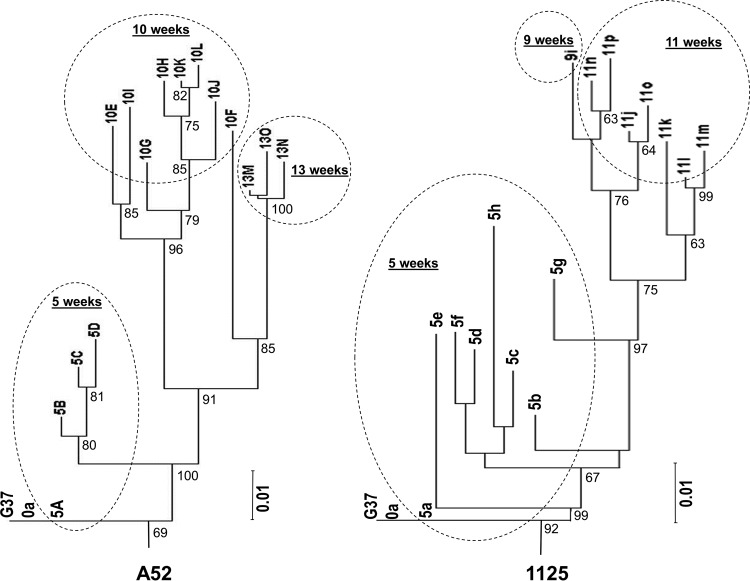

Clustering analysis of MG192 sequences.

To determine the relatedness of MG192 variants identified from different time points, we performed clustering analysis by using the neighbor-joining method. Figure 3 shows the results of clustering analysis of predicted MG192 amino acid sequences, which are similar to the results of nucleotide sequence analysis (data not shown). In animal A52, MG192 variants were clearly separated between different time points after infection except for one variant (5A) at 5 weeks p.i. and another variant (10F) at 10 weeks p.i. Variant 5A was identified in 2 of 8 plasmid clones, with a sequence identical to that of the parental G37 strain (Table 1 and data not shown), thus representing a small population that had survived the host immune or other selection pressure placed over the first 5 weeks. Variant 10F, detected at 10 weeks p.i. but clustered together with variants from 13 weeks p.i., is likely representing an intermediate population between these two time points (or the predecessor of variants at 13 weeks p.i.). In animal 1125, MG192 variants were separated between different time points with the following exception. Variant 5a, like 5A in animal A52, was a small population that had survived the selection pressure in the first 5 weeks. Variant 5g is likely representing an intermediate population that had survived the selection pressure between 5 and 9 weeks p.i. and presumably served as the predecessor of the variant 9i at 9 weeks p.i. The observation that all variants at 9 and 11 weeks were clustered together may suggest that a 2-week period is too short to select for significantly different variants.

FIG 3.

Phylogram trees based on the neighbor-joining method using predicted amino acid sequences of MG192 variants obtained from two chimpanzees, A52 and 1125, infected by M. genitalium. Both trees are rooted with the G37T MG192 sequence, with 1,000 random bootstrap resamplings. Bootstrap values >60% are indicated at nodes. Variants identified from each time point (weeks after inoculation) are enclosed by a dashed oval. See Materials and Methods for variant designations.

Strain typing studies.

An identical genotype was found in all isolates collected at different time points (including all uncloned mycoplasma cultures and selected MSCC clones) from both animals and compared to the published G37 T sequence, indicating that there was only a single M. genitalium strain and that the MG192 heterogeneity observed in both animals is not the result of coinfection with multiple strains. This observation, together with the finding of the MG192 sequence identity between the 0-week isolate from both animals and the published G37T sequence, also indicates the stability of the bacterial materials in spite of prolonged storage.

Confirmation of MG192 variants.

We performed variant-specific PCR on DNA samples prepared from original urethral swab isolates. Each selected variant specific for a given time point could be amplified in the original DNA sample obtained from that time point but not other time points (Fig. 2 and data not shown). Of special note is that three MG192 variant sequences (11n, 11o, and 11p in Table 2), which were identified by PCR and plasmid cloning from an MSCC clone (no. K20), could be reamplified by the variant-specific PCR from the MSCC clone but not from the original swab isolate (uncloned mycoplasma culture). One example of such variants was variant 11n, shown in Fig. 2.

Possibility of PCR-mediated DNA recombination between MG192 variants or between MG192 and MgPars.

When plasmids containing known MG192 or MgPar 9 sequences were mixed and used as the template to reamplify the MG192 variable region, we did not find any new, chimeric sequences by sequencing of 10 to 12 plasmid clones.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we investigated MG192 sequence variation over a 13-week course of infection in two chimpanzees inoculated with M. genitalium type strain G37T. MG192 sequence changes began within 5 weeks after infection. Initially, we attempted to see if the number of variants increased over time following infection by sequencing the same number of plasmid clones (e.g., five clones) at each time point. Such a trend was observed in isolates from chimpanzee A52 but not from chimpanzee 1125. In order to obtain more variants, we sequenced additional plasmid clones for each time point. A total of 14 and 16 MG192 variants, with 1 to 8 variants per time point, were identified from each of the two animals. It is likely that the MG192 variants detected may not represent all variants in each isolate studied and that additional variants could be detected if a larger number of plasmid clones were studied or using the newly developed high-throughput long-read PacBio SMRT sequencing technology (19), though currently this technology is not widely available or affordable (20, 24). Using average numbers of nucleotide and predicted amino acid changes at each time point, we observed a significant increase of sequence changes over time during an 11- to 13-week period of infection in both animals (Table 1). The majority of sequence changes were specific for different time points after infection. All sequence changes in each MG192 variant except for a single base change in two variants could be traced to a specific MgPar donor sequence of G37, consistent with DNA recombination between MG192 and MgPars as previously reported (6–8, 10). Genotyping studies found that all isolates had the same genotype as the parental G37T strain, indicating that the MG192 heterogeneity observed in both animals is not the result of coinfection with multiple strains.

Kinetic data from experimentally infected chimpanzees reinforce the hypothesis that MG192 variation is used primarily as a strategy to evade host immune defenses. First, MG192 nucleotide changes detected in both animals correlated well with predicted amino acid changes, which could result in epitope changes. This suggests that the changes of epitopes were driven by the host immune selection. Second, MG192 sequence variation began within 5 weeks after infection in both chimpanzees, consistent with the seroconversion time as previously reported for these two animals (2). Third, with the progression of infection, sequence changes accumulated in the MG192 variable region, and most variants were present at particular time points, suggesting that the sequence shift is a result of the changing immune response of the host during infection and that selection pressure is dependent on unique immune responses at each time point. Of note, segregation of MG192 variants started at 5 weeks p.i. between the two animals inoculated with the same mycoplasma clone, implying the role of host environment in the selection of MG192 variants as observed previously in studies of humans with M. genitalium infection (5).

In this study, we observed highly heterogeneous MG192 sequences within uncloned M. genitalium isolates from both animals, consistent with previous studies of urine and swab specimens from M. genitalium-infected patients (5–7, 9, 10). All these sequences were obtained by PCR followed by sequencing of plasmid clones. This raises the concern of PCR-mediated DNA recombination, as has been shown in studying heterogeneous genetic materials such as multigene families or repetitive sequences in other organisms (21). The data from the present study suggest an absence of PCR-mediated recombination and confirm the presence of intrastrain heterogeneity of the MG192 gene. First, MG192 variant sequences identified by PCR and plasmid cloning could be reamplified from the original isolates using variant-specific primers. Second, most MG192 variant sequences were present in multiple plasmid clones and/or in two independent PCRs. Third, MG192 variant sequences (11j and 11k) identified by PCR and plasmid cloning of the 11-week uncloned swab isolate from chimpanzee no. 1125 were also found as the major two variants among 20 M. genitalium MSCC clones derived from the same swab isolate. Lastly, spike experiments using a mixture of two different MG192 sequences or a mixture of one MG192 and one MgPar 9 sequences as the template did not yield any chimeric sequences, suggesting that artificial recombination events, if occurred, would be rare.

In the present study, we detected MG192 sequence changes during the process of single-colony cloning of M. genitalium organisms. As shown in Table 2, three MG192 variants (11n, 11o, and 11p) were found in 1 of the 20 M. genitalium MSCC clones but could not be reamplified by variant-specific PCR from the original uncloned swab isolate. These variants are unlikely to be due to PCR artifacts because they could be reamplified by variant-specific PCR from the MSCC clone and one of them (variant 11n) was present as the major population (5 of 8 plasmid clones analyzed). This finding is not surprising, given that single-colony cloning of mycoplasma organisms usually involves several rounds of in vitro passage of the organisms and that previous studies have demonstrated sequence changes during in vitro passage of M. genitalium strain G37T (7, 10) or other mycoplasma species (22, 23). The occurrence of sequence change during the mycoplasma single-colony cloning process adds difficulty in studying in vivo sequence changes using this approach; that is to say, sequence changes detected from single-colony-cloned M. genitalium organisms may not reflect the natural history of genetic variation in vivo. The presence of spontaneous variation suggests that some MG192 variation is independent of immune selection but may form the basis for subsequent immune selection.

In summary, this study further confirms the high-level intrastrain heterogeneity of the MG192 gene. In vivo kinetic data from experimentally infected chimpanzees support the hypothesis that MG192 variation is used as a means of either immune evasion or host adaptation. Spontaneous variation detected in vitro suggests that some MG192 variation is independent of immune selection but may form the basis for subsequent immune selection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are deeply indebted to J. G. Tully, D. Taylor-Robinson, M. F. Barile, P. Snoy, and J. Cogan for their work with chimpanzees and for kindly providing us the specimens, without which our work would have been impossible. We also thank Mary Welch and Judy Burnett for technical assistance. We declare no conflicting interests relevant to the study.

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Taylor-Robinson D, Furr PM, Tully JG, Barile MF, Moller BR. 1987. Animal models of Mycoplasma genitalium urogenital infection. Isr J Med Sci 23:561–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor-Robinson D, Tully JG, Barile MF. 1985. Urethral infection in male chimpanzees produced experimentally by Mycoplasma genitalium. Br J Exp Pathol 66:95–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hjorth SV, Bjornelius E, Lidbrink P, Falk L, Dohn B, Berthelsen L, Ma L, Martin DH, Jensen JS. 2006. Sequence-based typing of Mycoplasma genitalium reveals sexual transmission. J Clin Microbiol 44:2078–2083. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00003-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horner P, Thomas B, Gilroy CB, Egger M, Taylor-Robinson D. 2001. Role of Mycoplasma genitalium and Ureaplasma urealyticum in acute and chronic nongonococcal urethritis. Clin Infect Dis 32:995–1003. doi: 10.1086/319594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma L, Mancuso M, Williams JA, Van Der Pol B, Fortenberry JD, Jia Q, Myers L, Martin DH. 2014. Extensive variation and rapid shift of the MG192 sequence in Mycoplasma genitalium strains from patients with chronic infection. Infect Immun 82:1326–1334. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01526-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iverson-Cabral SL, Astete SG, Cohen CR, Rocha EP, Totten PA. 2006. Intrastrain heterogeneity of the mgpB gene in Mycoplasma genitalium is extensive in vitro and in vivo and suggests that variation is generated via recombination with repetitive chromosomal sequences. Infect Immun 74:3715–3726. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00239-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iverson-Cabral SL, Astete SG, Cohen CR, Totten PA. 2007. mgpB and mgpC sequence diversity in Mycoplasma genitalium is generated by segmental reciprocal recombination with repetitive chromosomal sequences. Mol Microbiol 66:55–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen JS. 2006. Mycoplasma genitalium infections. Diagnosis, clinical aspects, and pathogenesis. Dan Med Bull 53:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma L, Jensen JS, Mancuso M, Hamasuna R, Jia Q, McGowin CL, Martin DH. 2010. Genetic variation in the complete MgPa operon and its repetitive chromosomal elements in clinical strains of Mycoplasma genitalium. PLoS One 5:e15660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma L, Jensen JS, Myers L, Burnett J, Welch M, Jia Q, Martin DH. 2007. Mycoplasma genitalium: an efficient strategy to generate genetic variation from a minimal genome. Mol Microbiol 66:220–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05911.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peterson SN, Bailey CC, Jensen JS, Borre MB, King ES, Bott KF, Hutchison CA III. 1995. Characterization of repetitive DNA in the Mycoplasma genitalium genome: possible role in the generation of antigenic variation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:11829–11833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Citti C, Nouvel LX, Baranowski E. 2010. Phase and antigenic variation in mycoplasmas. Future Microbiol 5:1073–1085. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood GE, Iverson-Cabral SL, Patton DL, Cummings PK, Cosgrove Sweeney YT, Totten PA. 2013. Persistence, immune response, and antigenic variation of Mycoplasma genitalium in an experimentally infected pig-tailed macaque (Macaca nemestrina). Infect Immun 81:2938–2951. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01322-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen JS, Hansen HT, Lind K. 1996. Isolation of Mycoplasma genitalium strains from the male urethra. J Clin Microbiol 34:286–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen JS, Bjornelius E, Dohn B, Lidbrink P. 2004. Use of TaqMan 5′ nuclease real-time PCR for quantitative detection of Mycoplasma genitalium DNA in males with and without urethritis who were attendees at a sexually transmitted disease clinic. J Clin Microbiol 42:683–692. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.2.683-692.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musatovova O, Herrera C, Baseman JB. 2006. Proximal region of the gene encoding cytadherence-related protein permits molecular typing of Mycoplasma genitalium clinical strains by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism. J Clin Microbiol 44:598–603. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.2.598-603.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma L, Taylor S, Jensen JS, Myers L, Lillis R, Martin DH. 2008. Short tandem repeat sequences in the Mycoplasma genitalium genome and their use in a multilocus genotyping system. BMC Microbiol 8:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraser CM, Gocayne JD, White O, Adams MD, Clayton RA, Fleischmann RD, Bult CJ, Kerlavage AR, Sutton G, Kelley JM, Fritchman RD, Weidman JF, Small KV, Sandusky M, Fuhrmann J, Nguyen D, Utterback TR, Saudek DM, Phillips CA, Merrick JM, Tomb JF, Dougherty BA, Bott KF, Hu PC, Lucier TS, Peterson SN, Smith HO, Hutchison CA III, Venter JC. 1995. The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science 270:397–403. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chin CS, Alexander DH, Marks P, Klammer AA, Drake J, Heiner C, Clum A, Copeland A, Huddleston J, Eichler EE, Turner SW, Korlach J. 2013. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat Methods 10:563–569. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiao X, Zheng X, Ma L, Kutty G, Gogineni E, Sun Q, Sherman BT, Hu X, Jones K, Raley C, Tran B, Munroe DJ, Stephens R, Liang D, Imamichi T, Kovacs JA, Lempicki RA, Huang DW. 2013. A benchmark study on error assessment and quality control of CCS reads derived from the PacBio RS. J Data Mining Genomics Proteomics 4:16008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyerhans A, Vartanian JP, Wain-Hobson S. 1990. DNA recombination during PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 18:1687–1691. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.7.1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosengarten R, Wise KS. 1990. Phenotypic switching in mycoplasmas: phase variation of diverse surface lipoproteins. Science 247:315–318. doi: 10.1126/science.1688663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosengarten R, Yogev D. 1996. Variant colony surface antigenic phenotypes within mycoplasma strain populations: implications for species identification and strain standardization. J Clin Microbiol 34:149–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma L, Chen Z, Huang DW, Kutty G, Ishihara M, Wang H, Abouelleil A, Bishop L, Davey E, Deng R, Deng X, Fan L, Fantoni G, Fitzgerald M, Gogineni E, Goldberg JM, Handley G, Hu X, Huber C, Jiao X, Jones K, Levin JZ, Liu Y, Macdonald P, Melnikov A, Raley C, Sassi M, Sherman BT, Song X, Sykes S, Tran B, Walsh L, Xia Y, Yang J, Young S, Zeng Q, Zheng X, Stephens R, Nusbaum C, Birren BW, Azadi P, Lempicki RA, Cuomo CA, Kovacs JA. Genome analysis of three Pneumocystis species reveals adaptation mechanisms to life exclusively in mammalian hosts. Nat Commun, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]