Abstract

Photoacoustic tomography, a hybrid imaging modality combining optical and ultrasound imaging, is gaining attention in the field of medical imaging. Typically, a Q-switched Nd:YAG laser is used to excite the tissue and generate photoacoustic signals. But, such photoacoustic imaging systems are difficult to translate into clinical applications owing to their high cost, bulky size often requiring an optical table to house such lasers. Moreover, the low pulse repetition rate of few tens of hertz prevents them from being used in high frame rate photoacoustic imaging. In this work, we have demonstrated up to 7000 Hz photoacoustic imaging (B-mode) and measured the flow rate of a fast moving object. We used a ~140 nanosecond pulsed laser diode as an excitation source and a clinical ultrasound imaging system to capture and display the photoacoustic images. The excitation laser is ~803 nm in wavelength with ~1.4 mJ energy per pulse. So far, the reported 2-dimensional photoacoustic B-scan imaging is only a few tens of frames per second using a clinical ultrasound system. Therefore, this is the first report on 2-dimensional photoacoustic B-scan imaging with 7000 frames per second. We have demonstrated phantom imaging to view and measure the flow rate of ink solution inside a tube. This fast photoacoustic imaging can be useful for various clinical applications including cardiac related problems, where the blood flow rate is quite high, or other dynamic studies.

OCIS codes: (110.5120) Photoacoustic imaging, (110.0110) Imaging systems, (140.2010) Diode laser arrays

1. Introduction

Photoacoustic tomography (PAT) is a hybrid, noninvasive imaging modality, combining both optical and ultrasound imaging, rapidly gaining importance in the field of biomedical imaging [1–5]. It has several potential clinical applications, such as breast cancer imaging, brain imaging, sentinel lymph node imaging, temperature monitoring, and many others [6–15]. It uses non-ionising laser pulses to irradiate the sample (e.g., biological tissues), leading to absorption of light energy to increase the local temperature (in the order of a few milli degrees), resulting in thermoelastic expansion and release of pressure waves known as photoacoustic (PA) waves. Ultrasound detectors (single or multiple or array detectors) acquire these PA waves outside the sample boundary. Reconstruction techniques are used to form the optical absorption map of the inside of the object [16–20]. PAT has several advantages including deeper penetration depth, good spatial resolution, and high soft tissue contrast in comparison to other optical imaging modality like optical microscopy or optical coherence tomography. It combines the high resolution of pure ultrasound imaging, and high contrast of pure optical imaging into a single modality. Ultrasound scattering is two to three orders of magnitude less than the optical scattering in biological tissues, making photoacoustic imaging overcome the fundamental depth limitations of existing pure optical imaging.

Light penetration into biological tissue is greater in the near-infrared (NIR) wavelength region. Therefore, pulsed lasers emitting NIR wavelength lights have been used for deep-tissue PAT imaging. PAT uses blood as an intrinsic contrast, but, when the signal from the blood is not strong enough other exogenous or extrinsic contrast agents can also be used (organic and inorganic contrast agents, such as gold nanoparticles, nanospheres, nanocages, carbon nanotubes etc.) [21–25]. For the light excitation source, usually, a Nd:YAG pump laser either pumps a dye laser or an Optical parametric oscillator (OPO) laser to generate light in the NIR wavelengths. But, these types of lasers are bulky (often requiring an optical table to house the laser), expensive, and slow (typical pulse repetition rate for such lasers is 10-20 Hz with ~100 mJ of energy per pulse), making the PAT system difficult to translate into clinical setup. Therefore, there is a need to develop PAT system which is compact, affordable, portable and have a higher frame rates [26, 27].

High frame rate PA imaging is also required in areas where a small region, undergoing rapid changes, needs to be imaged fast. The potential applications for such fast PAT system could be imaging of the motion of the heart valves, shape of heart, myocardial functions, or even monitoring circulating tumor cells in blood vessels. The velocity of blood in the aorta is ~40 cm/s, in the vena cava is ~15 cm/s, and in the capillaries is ~0.03 cm/s [28]. Another area where real-time PA imaging can be useful is in the imaging of circulating tumor cells (CTC) in blood stream (an indicator of the metastasis of cancer). Imaging CTC is most commonly performed ex vivo only. However, recently in vivo photoacoustic flow cytometry has been demonstrated with the injection of external contrast agent (gold nanoparticles) with good PA contrast [29, 30]. Since, melanoma has strong light absorption in the NIR wavelengths; it may not require any external contrast for the detection. Another potential area of application is to image the heartbeat of the rodents; they have approximately 400 beats per minute which can be imaged using the high speed PAT system [31]. Photoacoustic Microscopy (PAM) imaging was performed at 50 fps to image the microvasculature and heartbeat of the nude mice [32, 33]. However, PAM can only be used for shallower imaging depth. For deep tissue imaging, PAT is preferable.

There are two types of PAT systems. The first type is based on single element ultrasound transducer, where the transducer rotates around the sample and collects PA signal in a circular geometry (other geometries are also possible). These types of PAT systems are very slow and the mechanical scanning limits its use for clinical applications. Recently, it was shown that low cost, portable PAT systems can be built with reasonable imaging depth (up to 2 cm) with single element transducer [34]. This is the fastest reported PAT system till now with single element transducer with cross-sectional PAT imaging speed of 3 sec. Most traditional PAT system with single element transducer will take several minutes to take one cross-sectional PAT image. Therefore, making high frame rate PAT imaging with single element transducer is very challenging. The second type of PAT system consists of ultrasound array transducer, and a parallel data acquisition system. PAT of the cortical hemodynamics of small animal in vivo with a temporal resolution of 1.6 s using a custom build circular ring array transducer and parallel data acquisition system has been demonstrated [35]. However, such PAT system has limited application due to the inflexibility of the ring array transducer (circular and fixed size, hence, can be applied only to small animal brain imaging). Therefore, 3-dimensional spherical transducer arrays have been developed for volumetric photoacoustic imaging. Brain imaging for fast hemodynamic changes during inter-ictal epileptic seizures were done at 3 fps using such custom made spherical transducer array [36]. Functional three dimensional optoacoustic imaging free of motion artefacts was possible on the tissue vasculature with an OPO laser at 20 Hz [37]. They also reported functional neuronal optoacoustic imaging of the neuronal activation in the brain at 100 fps volumetric framerate [38]. In another study, functional volumetric imaging of the murine heart was done at 50 fps using a custom made spherical array ultrasound detection array [39]. Therefore, the maximum volumetric frame rate reported so far from photoacoustic tomography is 100 fps using curved array custom made transducers. However, such transducers are still not largely used in clinic. Moreover, they also need custom made parallel data acquisition systems, and therefore, cost can be quite high. Another approach is to modify a clinical ultrasound imaging system to incorporate photoacoustic imaging [13, 26, 40, 41]. Since clinical ultrasound systems are used by clinicians on a regular basis, they may have better acceptability by the clinical community (with additional photoacoustic feature). Moreover, clinical ultrasound imaging system gives the flexibility of the type of array transducers (linear, convex, phased array etc.) one can use depending on the application areas. With such systems real time phantom imaging up to 15 mm depth was done at 20 fps [26]. In another study done with the OPO-Ultrasound system, in vivo real time imaging of blood vessels in rat was performed at 20 fps [40]. Therefore, the maximum frame rate reported so far for 2-dimensional photoacoustic B-scan imaging is 20 fps using a clinical ultrasound system.

In this work, we report up to 7000 fps PAT imaging (B-scans) by use of a low cost, light weight pulsed laser diode (PLD). The PLD has a maximum pulse repetition frequency of 7000 Hz with maximum pulse energy of ~1.4 mJ. The PLD together with clinical ultrasound imaging system enabled very high frame rate photoacoustic B-scan imaging. Phantom experiments were conducted to demonstrate the high frame rate imaging capability. The flow of black ink was imaged at high frame rate PA imaging. Various flow rates were used from 3 cm/s to 14 cm/s. From the PA images we were able to measure the flow rate accurately as well. For comparison, a low pulse repetition rate Nd:YAG pumped OPO laser (standard laser used for most PAT system) based PA imaging, and normal ultrasound imaging were also done.

2. Methods

2.1 PAT imaging system

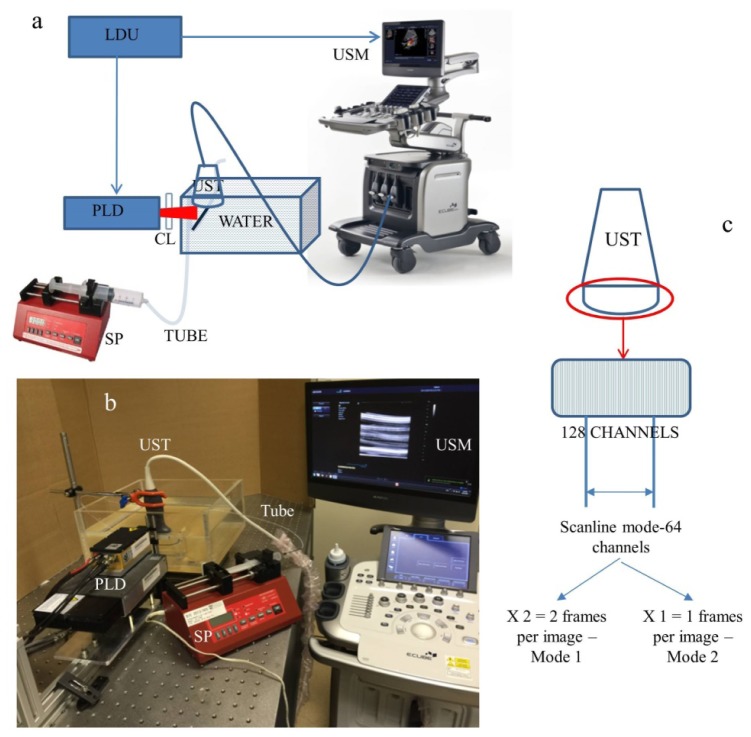

The experimental set up is shown in Fig. 1(a). For this work we have used a clinical research ultrasound system (ECUBE 12R, Alpinion, South Korea) capable of dual modal imaging (both photoacoustic imaging as well as ultrasound imaging). To use the system in the photoacoustic mode, we need to provide the laser excitation and a controlling unit which can synchronize the laser excitation and ultrasound detection. For the high frame rate photoacoustic imaging we used the pulsed laser diode (Quantel DQ-Q1910-SA-TEC), which can provide ~136 ns pulses at a near-infrared (NIR) wavelength of 803 nm, and maximum pulse energy of ~1.4 mJ. It has a pulse repetition rate of 7000 Hz (max). The PLD generates a rectangular laser beam which diverges with an angle of ~11.5, and ~0.65 degree along slow and fast axes, respectively. The PLD is controlled by the laser driver unit (LDU) which consists of a temperature controller (LaridTech, MTTC1410), a 12 V power supply (Voltcraft, PPS-11810), a variable power supply (to vary the laser output power), and a function generator (to control the laser repetition rate). The pulse energy and repetition rate can be controlled independently with the variable power supply (BASETech, BT-153), and the function generator (FG250D, Funktionsgenerator), respectively. The function generator provides a TTL (Transistor-Transistor Logic) signal to synchronize the laser excitation and the ultrasound data acquisition by the clinical ultrasound system. A cylindrical lens (CL) was used in front of the laser window to make the laser beam narrower. On the sample the laser beam spot was around 15 mm x 5 mm. The photoacoustic signals generated were acquired by a linear array transducer (L3-12 transducer, compatible with the Ecube ultrasound system) consisting of 128 array elements. The probe has a center frequency of 8.5 MHz (95% fractional bandwidth), array element pitch 0.3 mm and elevation height 4.5 mm. The Ecube system has a 40 MHz sampling frequency and 12 bit ADC to acquire the data and a data transfer speed of 6 Gb/s. Figure 1(b) shows the picture of the experimental set up with all the components. This setup is called as PLD-PAT system.

Fig. 1.

a) Schematic of the PLD-PAT ultrasound setup; PLD: Pulsed laser diode, UST: ultrasound array transducer, CL: cylindrical lens, SP: syringe pump, LDU: laser driver unit, USM: clinical ultrasound machine. b) Image showing all the components of the PLD-PAT imaging setup for flow imaging. c) The L3-12 linear array ultrasound transducer which can be operated in 2 different modes. One using all the 128 arrays elements, and the other using 64 channels elements only (element numbers 1-64 or 65-128).

A similar set up was done with the OPO laser as light excitation source, which is typically used for most PAT systems for deep tissue imaging. Since these types of lasers have lower repetition rates (typically 10-100 Hz), but higher pulse energy, they cannot provide very high frame rate PAT images (the maximum frame rate one can obtain is same as the laser pulse repetition rate i.e., 10-100 Hz). The excitation laser consists the OPO (Continuum, Surelite OPO) laser pumped by a 532 nm Nd:YAG pump laser (Continuum, Surelite Ex). The OPO generates 5 ns duration pulses at 10 Hz repetition rate (maximum) with wavelength tunable from 680 nm to 2500 nm. For the experiments it was tuned to 803 nm since the PLD also operates at that wavelength. The laser beam spot size falling on the sample was ~1.5 cm in diameter. Like before the PA images were captured by the L3-12 linear array transducer in the Ecube ultrasound imaging system. The trigger out from the pump laser synchronized the data acquisition on the Ecube system. This setup is called as OPO-PAT system.

2.2 PA data acquisition and image formation

To operate the Ecube ultrasound imaging system in the photoacoustic mode, one needs to go in the research mode. In the research mode, the instructions can be written using a python script to set the parameters like imaging depth, data acquisition modes, number of frames to be acquired, type of data to be saved etc. The PA signal generated by the laser excitation is acquired by the array transducer L3-12 (128 element linear array with center frequency of 8.5 MHz, 95% fractional bandwidth, array element pitch 0.3 mm, and elevation height 4.5 mm). However, the ultrasound system has 64 parallel data acquisition hardware. Figure 1(c) shows how the data acquisition in photoacoustic mode works. The data acquisition is done by 64 channels of the receiver each time. This is fixed and cannot be modified. Therefore, in one single laser pulse the PA signals from 64 array elements can be captured. To collect all the 128 array element data we need 2 laser pulses. Thus the system can be operated in two different modes. When operated in mode 1, there are two frames per PA image (i.e., the 64 channel receiver operates twice which requires two trigger from the laser), thus the effective frame rate is half the laser repetition rate. For example, if the PLD was set to run at 7000 Hz, the effective frame rate for PA B-mode imaging was 3500 fps (7000/2 = 3500). When OPO was used as excitation source we could only achieve 5 fps (OPO runs at 10 Hz repetition rate) PA imaging in this mode. On the other hand in mode 2, only half of the transducer array elements (64 elements) can be used and it requires only a single laser trigger to capture a B-mode PA image. Thus, the frame rate of the PA images is same as the laser pulse repetition rate. In this mode, we could achieve a maximum frame rate of 7000 fps using PLD and 10 fps using the OPO laser. The acquired PA signals then go through a series of inbuilt filers for the image processing. It also allows the user to add and custom modify the filter module to suit for the individual needs. No custom made filters were added for this work. The signal first enters the source filter and gets processed. It moves to the custom filter adapter, and then to the B-filter. B-filter is followed by the scan conversion filter, and finally the render filter. The output from the render filter is displayed on the Ecube monitor as PAT images. At the same time these beamformed and scan converted PA data can also be saved on the hard drive of the Ecube system. The raw channel data can be saved into the hard drive as well. For this work only beam formed and scan converted PA data is saved. We have chosen to save a total of 8000 frames (B-scans) when PLD was used as excitation source, and 20 frames when OPO was used as excitation source. We have used the saved frames later and processed them in MATLAB for measuring the flow rate as well as to create the movie clips (visualizations).

2.3 Ultrasound imaging

For comparison ultrasound imaging was also done. In the ultrasound mode, the ultrasound machine captures the B-mode ultrasound data and after beamforming and scan conversion the images are displayed on the screen of the Ecube system. For the ultrasound imaging there is no need for external triggering, as the system operates on internal triggering. Thus the external trigger was removed. The L3-12 ultrasound transducer performed both sending and the receiving of ultrasound waves. All the ultrasound data (RF signals, IQ data, Beam formed data, and Scan converted data) can be saved in the hard drive of the Ecube for post processing if needed. However, for this work we didn’t do any post processing for the ultrasound images.

2.4 Phantom experiments

To demonstrate the capability of the imaging system providing high frame rate PA imaging, we carried out flow imaging. A low density polyethylene (LDPE) transparent tube of inner diameter 1.15 mm was placed in the water bath. The tube was positioned such a way that the laser beam falls on it. Black ink (which has good optical absorption at 803 nm wavelength and can produce PA signal) was injected into the tube using a 10 mL syringe with a 24G needle. The optical absorption of the black ink is ~5 cm−1, very similar to that of blood, but less than Indocyanine Green (ICG) at 803 nm excitation wavelength [34, 42]. The flow rate of black ink was controlled with a programmable syringe pump (AL-1000, World precision instruments). The transducer was placed at a distance of 1 cm from the tube with a total imaging depth of 2 to 3 cm. The ink flow rates inside the LDPE tube used for the experiments were 3 cm/s, 6 cm/s, 10 cm/s, and 14 cm/s. The specified flow rates were chosen to demonstrate that with the high frame rate PA imaging system we can image and accurately find the various flow rates from the PA images.

The flow rate of the ink flow was calculated from the saved PA images. The distance travelled by the ink is measured from the high contrast air-ink interface in the PA B-scan images. The PA image (beamformed) has a pixel size of 0.03 cm. The pixel size was determined by the beam former parameter. From the saved PA image the distance moved by the ink in a given period of time was calculated. A start frame and an end frame was chosen, and if the ink flow moved by a distance d in N frames (), then the flow rate is calculated as, .

2.5 Laser safety

When PAT is used to image subjects in vivo, the maximum permissible pulse energy and the maximum permissible pulse repetition rate are governed by the ANSI laser safety standards [43]. The safety limits for the skin depend on the optical wavelength, pulse duration, exposure duration, and exposure aperture. In the spectral region of 700-1050 nm, the maximum permissible exposure (MPE) on the skin surface by any single laser pulse should not exceed 20 × 102(λ-700)/1000 mJ/cm2 (λ is the wavelength in nm) [43]. Therefore, at 803 nm the MPE for a single pulse exposure is ~31 mJ/cm2. However, for our imaging purpose the exposure time was roughly 2 seconds with multiple laser pulses. The MPE for exposure time t = 2 sec is given by 1.1 × 102(λ-700)/1000 × t0.25 J/cm2 ( = 1.1 × 102(803-700)/1000 × 20.25 J/cm2 = 2.07 J/cm2) [43]. Since the PLD was operating at 7000 Hz (total number of laser pulses in 2 sec = 2 × 7000 = 14000), the MPE becomes 0.15 mJ/cm2 (2.07/14000) per pulse. In our imaging system, the pulsed diode laser provided maximum ~1.4 mJ pulse energy, and the laser beam was spread over an area of ~0.75 cm2 (~1.5 cm × 0.5 cm). Therefore, the laser fluence on the sample surface was ~1.9 mJ/cm2 (1.4/0.75). Thus, in the PLD-PAT imaging system the laser fluence on the sample surface was above the MPE.

For OPO excitation, the OPO laser energy output was at ~40 mJ per pulse at 803 nm on the sample surface (~1.5 cm diameter spot). Thus the fluence on the sample surface was ~22.6 mJ/cm2. Thus the fluence is within the ANSI safety limit.

The MPE safety limit was not strictly followed in case of phantom imaging with the PLD-PAT system in this work. Moreover, the aim of this study was to demonstrate the possibility of high frame rate imaging at 7000 fps. Thus, no frame averaging was not done to improve the signal-to-noise (when the laser is operated at lower energy the PA signals will be weaker and averaging will be required). For future in vivo experiments, the fluence on the sample surface can be reduced by various ways – a) spreading the beam over a larger area, b) reducing the pulse repetition rate, c) reducing the exposure time less than 2 sec, or d) reducing the laser power output by controlling the power supply itself. Among the four, reducing the pulse repetition rate or reducing the exposure time is the best way to optimize the SNR and still be within the ANSI safety limit. The SNR decreases linearly with the energy of the pulses, whereas averaging more pulses only increases the SNR by square root of the number of averages. Therefore, it is preferable to use lower frame rates to maximize SNR, which is particularly important for the clinical translation [37]. On the other hand, reducing the exposure time will also help to be within the ANSI safety limit. However, if one needs to do continuous monitoring using PA imaging for long time, this may not be feasible.

3. Results and discussion

As described earlier, a tube was used with black ink flowing through it with a specified flow rate. At first it is shown that with just ultrasound imaging it is not possible to see the ink flowing, as ink does not have any ultrasound contrast. However, ink is a good optical absorber and will be visible in photoacoustic imaging. Figure 2 shows the screenshot of the ultrasound B-mode image obtained with the Ecube. A depth of 2 cm was imaged and the transducer was placed at a distance of 1 cm from the tube with ink flow. The flow rate of the black ink was maintained at 3 cm/s. The tube part of the image alone is enlarged and shown on the right. Only the LDPE tube boundaries are visible in the ultrasound image. Obviously the flow of the ink inside the tube is not visible as ink does not have good ultrasound contrast.

Fig. 2.

Ultrasound B-mode image on the ECUBE system showing the flow of the black ink inside the tube. The enlarged tube region shows that we can see the boundary of the tube, but no flow can be visible in the ultrasound images, as ink does not have a good ultrasound contrast.

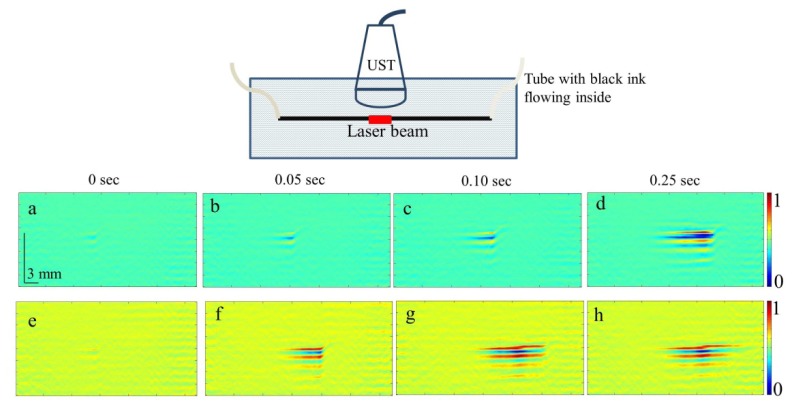

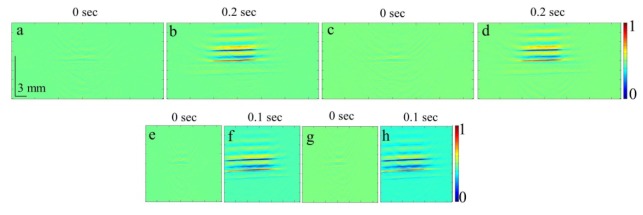

PA imaging was done for the different flowrates at the two different modes of the data acquisition as discussed previously. Figures 3 and 4 show the PA B-scan images obtained from the PLD-PAT system. Figure 3 shows the flow of the ink in the tube at various time points when the transducer was operated in mode 1. In this mode 3500 fps PA images were recorded. Figure 4 shows the same PA images when the transducer was operated in mode 2. In this mode 7000 fps PA images were recorded. The PA images represented here are at time points t = 0 s [Figs. 3(a), 3(e), 4(a), 4(e)], 0.05 s [Figs. 3(b), 3(f), 4(b), 4(f)], 0.1 s [Figs. 3(c), 3(g), 4(c), 4(g)], and 0.25 s [Figs. 3(d), 3(h), 4(d), 4(h)]. For representative purposes, only two different flow rates are shown here; 3 cm/s [Figs. 3(a)-3(d), 4(a)-4(d)], and 14 cm/s [Figs. 3(e)-3(h), 4(e)-4(h)]. It is clearly seen that the ink is flowing through the tube from both Figs. 3 and 4 (high contrast air-ink interface is moving in the PA B-scan images). The complete flow is shown in the video clips for all the flow rates for which PA images were recorded. Visualization 1 (8.5MB, MP4) , Visualization 2 (5MB, MP4) , Visualization 3 (4MB, MP4) , and Visualization 4 (3.3MB, MP4) show the flow of the ink captured at 3500 fps for the ink flow rates 3 cm/s, 6 cm/s, 10 cm/s, and 14 cm/s, respectively. Visualization 5 (11.1MB, MP4) , Visualization 6 (6.7MB, MP4) , Visualization 7 (4.3MB, MP4) , and Visualization 8 (3.7MB, MP4) show the flow of the ink captured at 7000 fps for the same flowrates as before. Visualization 1 (8.5MB, MP4) , Visualization 2 (5MB, MP4) , Visualization 3 (4MB, MP4) , and Visualization 4 (3.3MB, MP4) are shown at 0.04X speed and Visualization 5 (11.1MB, MP4) , Visualization 6 (6.7MB, MP4) , Visualization 7 (4.3MB, MP4) , and Visualization 8 (3.7MB, MP4) are shown at 0.02X speed for better viewing. 175 frames are being recorded in 0.05 s when operated at 3500 fps, and 350 frames are being recorded in 0.05 s when operated at 7000 fps. The set of images here show the ink flowing inside the tube for a time period of 0.25 s. From the images, the gradual flow of the ink can be observed at different time points. The distance moved by the ink is approximately 15 mm which is consistent with the laser beam width. However, depending on the ink flow rates the time taken to move that distance are different, which can be observed from the images as well as from the movie clips.

Fig. 3.

Set of PA images showing the ink flow at various time points obtained with PLD-PAT system. PA imaging was done at a frame rate of 3500 fps. Schematic of the setup is shown on the top. (a-d) Flow rate was 3 cm/s, (e-h) flow rate was 14 cm/s. All images have same scale bars shown in (a). The normalised colormap is shown on the right. Movie clips (Visualization 1 (8.5MB, MP4) , Visualization 2 (5MB, MP4) , Visualization 3 (4MB, MP4) , and Visualization 4 (3.3MB, MP4) ) show the ink flowing through the tube with 3500 fps PA B-scan imaging.

Fig. 4.

Set of PA images showing the ink flow at various time points with the PLD-PAT system. PA imaging was done at a frame rate of 7000 fps. (a-d) Flow rate was 3 cm/s, (e-h) flow rate was 14 cm/s. All images have same scale bar shown in (a). The normalized colormap is shown on the right. Movie clips (Visualization 5 (11.1MB, MP4) , Visualization 6 (6.7MB, MP4) , Visualization 7 (4.3MB, MP4) , and Visualization 8 (3.7MB, MP4) ) show the ink flowing through the tube with 7000 fps PA B-scan imaging.

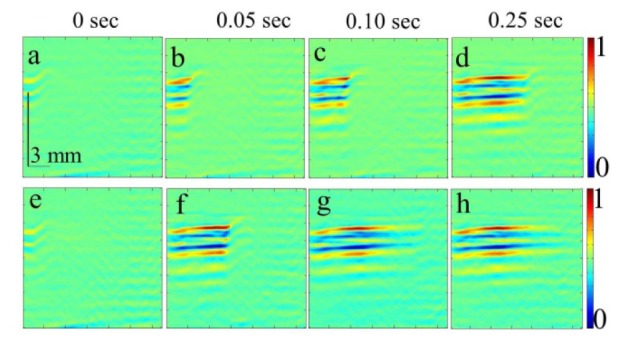

The same sets of experiments were carried out with the OPO-PAT system. As mentioned before, when the Ecube was operated in mode 1, PA images was recorded at 5 fps and when the Ecube was operated in mode 2, PA images were recorded at 10 fps. The PA images represented here are at time points t = 0 s [Figs. 5(a), 5(c), 5(e), 5(g)], 0.2 s [Figs. 5(b), 5(d), 0.1 s [Figs. 5(f), 5(h)]. For representative purposes, only two different flow rates are shown here; 3 cm/s [Figs. 5(a), 5(b), 5(e), 5(f)], and 14 cm/s [Figs. 5(c), 5(d), 5(g), 5(h))]. The OPO-PAT system at best can take PA B-scan images at 0.1 s interval (10 fps). Thus, the two time points at which PA images were captured at t = 0 s and t = 0.1 s (for 5 fps PA acquisition the frames are at t = 0 s and t = 0.2 s). It can be observed that the ink has flowed distance of approximately ~15 mm which is the total imaging window for the OPO laser beam within just 1 frame and the flow of the ink cannot be visualized as it was observed with PLD-PAT system (as evident in the visualization as well as PA static images).

Fig. 5.

Set of PA images showing the ink flow at various time points as obtained by OPO-PAT system. (a-d) PA imaging was done at a frame rate of 5 fps and (e-h) at a frame rate of 10 fps. (a,b,e,f) Flow rate was 3 cm/s, (c,d,g,h) flow rate was 14 cm/s. All the images have same scale bars as shown in (a). The normalized colormap is shown on the right.

To substantiate that from the high frame rate PA images we are getting the flow measurement correctly, we processed the saved PA data into MATLAB. Table 1 shows the comparison between the actual flow rates (as controlled by the syringe pump) with the flow rates calculated from the PA images. For example, when the ink flow rate is 3 cm/s (as recorded form the syringe pump) at 3500 fps PA imaging, the ink moves a distance of 2.1 mm in 0.057 seconds (i.e. 200 frames recorded), thus the flow rate as calculated from the PA image is 3.7 cm/s. Similarly, calculations were done for the all the other flow rates PA data. From the comparison in Table 1 it can be observed that the actual flow rate and the calculated flow rate from the PA images are very consistent for both 3500 fps and 7000 fps PA imaging.

Table 1. Comparison of the flow rates as controlled from the syringe pump and measured from the PA images from the PLD-PAT system.

| Frame rate | Measured flowrate (cm/s) | Calculated flowrate (cm/s) |

|---|---|---|

| 3500 | 3 | 3.7 |

| 3500 | 6 | 6.5 |

| 3500 | 10 | 10.5 |

| 3500 | 14 | 14.7 |

| 7000 | 3 | 3.6 |

| 7000 | 6 | 6.3 |

| 7000 | 10 | 10.5 |

| 7000 | 14 | 14.7 |

The maximum possible frame rate with the current PLD-PAT system is 7000 fps. This is mainly constrained by the excitation laser source pulse repetition rate, data acquisition modes, imaging depth etc. Up to 14 cm/s ink flow rate PA imaging was demonstrated in this work. However, a much higher flowrates can be visualized with the system. For the data acquisition mode 2, only 64 channels were used for PA signal acquisition. The distance of each pixel on the PA image is 0.3 mm. From one frame to the next frame, one can measure a maximum distance of up to 64*0.3 mm = 19.2 mm. Hence, the theoretical maximum flowrate that can be captured by this system is 134.4 m/s [19.2 mm x 7000 /s]. When the imaging is done in mode 1, two frames needs to be acquired to obtain a single PA image, one can image a larger area with this mode, whereas with the mode 2 since only one frame is captured for a single PA B-mode image the imaging area will be half of that in mode 1. But, for applications which require imaging to be done in a small area at a high framerate mode 2 is more preferred. The frame rate can be increased further if lasers are available with higher repetition rate. At present, the maximum imaging depth is (1/7000)*1540 m/s = ~22 cm. This depth is far more than what photoacoustic imaging can reach at the moment. The current system has certain drawback as well. The linear array transducer has a limited field of view. As a result it introduces artefacts in comparison to the circular array/spherical array transducer.

4. Conclusion

In this work, it was demonstrated that high frame rate photoacoustic imaging is possible using the PLD-PAT clinical ultrasound system. A very high frame rate of 7000 fps PA B-scan imaging is feasible with the PLD and Ecube clinical ultrasound imaging system, whereas with the OPO lasers only 10 fps (max) PA imaging is possible. With such a high frame rate of 7000 fps flow rate upto 134.4 m/s (theoretical) can be captured. It was shown that the flow can be visualized as well as accurate flow measurements can be done from the PA B-mode images obtained from the PLD-PAT system with various flow rates 3 cm/s to 14 cm/s. Future studies will be conducted to explore the various in vivo applications where high frame rate PA imaging would be beneficial, like imaging circulating tumor cells, heart valves, blood vessel etc. The PLD-PAT clinical system has a few limitations and challenges, such as limited view artefacts (caused by the linear array transducer), multiple acoustic reflections degrading the image quality, poor signal-to-noise due to lower laser pulse energy, and integrating the laser light source inside the ultrasound probe. However, the PLD being low cost, portable, and easy to handle may be easier to translate to clinical applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support from the Tier 1 grant funded by the Ministry of Education in Singapore (RG31/14: M4011276).

References and links

- 1.Taruttis A., Ntziachristos V., “Advances in real-time multispectral optoacoustic imaging and its applications,” Nat. Photonics 9(4), 219–227 (2015). 10.1038/nphoton.2015.29 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang L. V., Hu S., “Photoacoustic Tomography: In Vivo Imaging from Organelles to Organs,” Science 335(6075), 1458–1462 (2012). 10.1126/science.1216210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beard P., “Biomedical photoacoustic imaging,” Interface Focus 1(4), 602–631 (2011). 10.1098/rsfs.2011.0028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L. V., “Multiscale photoacoustic microscopy and computed tomography,” Nat. Photonics 3(9), 503–509 (2009). 10.1038/nphoton.2009.157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang L. V., “Prospects of photoacoustic tomography,” Med. Phys. 35(12), 5758–5767 (2008). 10.1118/1.3013698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li R., Wang P., Lan L., Lloyd F. P., Jr, Goergen C. J., Chen S., Cheng J.-X., “Assessing breast tumor margin by multispectral photoacoustic tomography,” Biomed. Opt. Express 6(4), 1273–1281 (2015). 10.1364/BOE.6.001273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diot G., Dima A., Ntziachristos V., “Multispectral opto-acoustic tomography of exercised muscle oxygenation,” Opt. Lett. 40(7), 1496–1499 (2015). 10.1364/OL.40.001496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen B. Z., Yang J. G., Wu D., Zeng D. W., Yi Y., Yang N., Jiang H. B., “Photoacoustic imaging of cerebral hypoperfusion during acupuncture,” Biomed. Opt. Express 6(9), 3225–3234 (2015). 10.1364/BOE.6.003225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X., Heldermon C. D., Yao L., Xi L., Jiang H., “High resolution functional photoacoustic tomography of breast cancer,” Med. Phys. 42(9), 5321–5328 (2015). 10.1118/1.4928598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Es P., Biswas S. K., Bernelot Moens H. J., Steenbergen W., Manohar S., “Initial results of finger imaging using photoacoustic computed tomography,” J. Biomed. Opt. 19(6), 060501 (2014). 10.1117/1.JBO.19.6.060501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nasiriavanaki M., Xia J., Wan H., Bauer A. Q., Culver J. P., Wang L. V., “High-resolution photoacoustic tomography of resting-state functional connectivity in the mouse brain,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111(1), 21–26 (2014). 10.1073/pnas.1311868111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xia W., Piras D., Singh M. K. A., van Hespen J. C. G., van Leeuwen T. G., Steenbergen W., Manohar S., “Design and evaluation of a laboratory prototype system for 3D photoacoustic full breast tomography,” Biomed. Opt. Express 4(11), 2555–2569 (2013). 10.1364/BOE.4.002555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erpelding T. N., Kim C., Pramanik M., Jankovic L., Maslov K., Guo Z., Margenthaler J. A., Pashley M. D., Wang L. V., “Sentinel lymph nodes in the rat: noninvasive photoacoustic and US imaging with a clinical US system,” Radiology 256(1), 102–110 (2010). 10.1148/radiol.10091772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pramanik M., Wang L. V., “Thermoacoustic and photoacoustic sensing of temperature,” J. Biomed. Opt. 14(5), 054024 (2009). 10.1117/1.3247155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pramanik M., Ku G., Li C., Wang L. V., “Design and evaluation of a novel breast cancer detection system combining both thermoacoustic (TA) and photoacoustic (PA) tomography,” Med. Phys. 35(6), 2218–2223 (2008). 10.1118/1.2911157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang H., Bustamante G., Peterson R., Ye J. Y., “An adaptive filtered back-projection for photoacoustic image reconstruction,” Med. Phys. 42(5), 2169–2178 (2015). 10.1118/1.4915532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pramanik M., “Improving tangential resolution with a modified delay-and-sum reconstruction algorithm in photoacoustic and thermoacoustic tomography,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 31(3), 621–627 (2014). 10.1364/JOSAA.31.000621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lutzweiler C., Deán-Ben X. L., Razansky D., “Expediting model-based optoacoustic reconstructions with tomographic symmetries,” Med. Phys. 41(1), 013302 (2014). 10.1118/1.4846055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prakash J., Raju A. S., Shaw C. B., Pramanik M., Yalavarthy P. K., “Basis pursuit deconvolution for improving model-based reconstructed images in photoacoustic tomography,” Biomed. Opt. Express 5(5), 1363–1377 (2014). 10.1364/BOE.5.001363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang C., Wang K., Nie L., Wang L. V., Anastasio M. A., “Full-wave iterative image reconstruction in photoacoustic tomography with acoustically inhomogeneous media,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 32(6), 1097–1110 (2013). 10.1109/TMI.2013.2254496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li W., Chen X., “Gold nanoparticles for photoacoustic imaging,” Nanomedicine (Lond.) 10(2), 299–320 (2015). 10.2217/nnm.14.169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim C., Favazza C., Wang L. V., “In vivo photoacoustic tomography of chemicals: high-resolution functional and molecular optical imaging at new depths,” Chem. Rev. 110(5), 2756–2782 (2010). 10.1021/cr900266s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pramanik M., Swierczewska M., Green D., Sitharaman B., Wang L. V., “Single-walled carbon nanotubes as a multimodal-thermoacoustic and photoacoustic-contrast agent,” J. Biomed. Opt. 14(3), 034018 (2009). 10.1117/1.3147407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De la Zerda A., Zavaleta C., Keren S., Vaithilingam S., Bodapati S., Liu Z., Levi J., Smith B. R., Ma T.-J., Oralkan O., Cheng Z., Chen X., Dai H., Khuri-Yakub B. T., Gambhir S. S., “Carbon nanotubes as photoacoustic molecular imaging agents in living mice,” Nat. Nanotechnol. 3(9), 557–562 (2008). 10.1038/nnano.2008.231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang X., Skrabalak S. E., Li Z.-Y., Xia Y., Wang L. V., “Photoacoustic Tomography of a Rat Cerebral Cortex in vivo with Au Nanocages as an Optical Contrast Agent,” Nano Lett. 7(12), 3798–3802 (2007). 10.1021/nl072349r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daoudi K., van den Berg P. J., Rabot O., Kohl A., Tisserand S., Brands P., Steenbergen W., “Handheld probe integrating laser diode and ultrasound transducer array for ultrasound/photoacoustic dual modality imaging,” Opt. Express 22(21), 26365–26374 (2014). 10.1364/OE.22.026365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daoudi K., van den Berg P. J., Rabot O., Kohl A., Tisserand S., Brands P., Steenbergen W., “Handheld probe for portable high frame photoacoustic/ultrasound imaging system,” Proc. SPIE 8581, 85812I (2013). 10.1117/12.2003655 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerard B. D., Tortora J., Principles of Anatomy and Physiology (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1993). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galanzha E. I., Zharov V. P., “Circulating tumor cell detection and capture by photoacoustic flow cytometry in vivo and ex vivo,” Cancers (Basel) 5(4), 1691–1738 (2013). 10.3390/cancers5041691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Brien C. M., Rood K. D., Bhattacharyya K., DeSouza T., Sengupta S., Gupta S. K., Mosley J. D., Goldschmidt B. S., Sharma N., Viator J. A., “Capture of circulating tumor cells using photoacoustic flowmetry and two phase flow,” J. Biomed. Opt. 17(6), 061221 (2012). 10.1117/1.JBO.17.6.061221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azar T., Sharp J., Lawson D., “Heart Rates of Male and Female Sprague-Dawley and Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats Housed Singly or in Groups,” J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 50(2), 175–184 (2011). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zemp R. J., Song L., Bitton R., Shung K. K., Wang L. V., “Realtime photoacoustic microscopy of murine cardiovascular dynamics,” Opt. Express 16(22), 18551–18556 (2008). 10.1364/OE.16.018551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zemp R. J., Song L., Bitton R., Shung K. K., Wang L. V., “Realtime photoacoustic microscopy in vivo with a 30-MHz ultrasound array transducer,” Opt. Express 16(11), 7915–7928 (2008). 10.1364/OE.16.007915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Upputuri P. K., Pramanik M., “Performance characterization of low-cost, high-speed, portable pulsed laser diode photoacoustic tomography (PLD-PAT) system,” Biomed. Opt. Express 6(10), 4118–4129 (2015). 10.1364/BOE.6.004118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li C., Aguirre A., Gamelin J., Maurudis A., Zhu Q., Wang L. V., “Real-time photoacoustic tomography of cortical hemodynamics in small animals,” J. Biomed. Opt. 15(1), 010509 (2010). 10.1117/1.3302807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiang L., Wang B., Ji L., Jiang H., “4-D photoacoustic tomography,” Sci. Rep. 3, 1113 (2013). 10.1038/srep01113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deán-Ben X. L., Bay E., Razansky D., “Functional optoacoustic imaging of moving objects using microsecond-delay acquisition of multispectral three-dimensional tomographic data,” Sci. Rep. 4, 5878 (2014). 10.1038/srep05878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sela G., Lauri A., Deán-Ben X. L., Kneipp M., Ntziachristos V., Shoham S., Westmeyer G. G., Razansky D., “Functional optoacoustic neuro-tomography (FONT) for whole-brain monitoring of calcium indicators,” arXiv preprint arXiv. 1501, 2450 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deán-Ben X. L., Ford S. J., Razansky D., “High-frame rate four dimensional optoacoustic tomography enables visualization of cardiovascular dynamics and mouse heart perfusion,” Sci. Rep. 5, 10133 (2015). 10.1038/srep10133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montilla L. G., Olafsson R., Bauer D. R., Witte R. S., “Real-time photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging: a simple solution for clinical ultrasound systems with linear arrays,” Phys. Med. Biol. 58(1), N1–N12 (2013). 10.1088/0031-9155/58/1/N1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim C., Erpelding T. N., Maslov K., Jankovic L., Akers W. J., Song L., Achilefu S., Margenthaler J. A., Pashley M. D., Wang L. V., “Handheld array-based photoacoustic probe for guiding needle biopsy of sentinel lymph nodes,” J. Biomed. Opt. 15(4), 046010 (2010). 10.1117/1.3469829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Upputuri P. K., Pramanik M., “Pulsed laser diode based optoacoustic imaging of biological tissues,” Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 1(4), 045010 (2015). 10.1088/2057-1976/1/4/045010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.American National Standard for Safe Use of Lasers, ANSI Standards Z136.1–2000, NY: (2000). [Google Scholar]