Abstract

In Paracoccus denitrificans, three CRP/FNR family regulatory proteins, NarR, NnrR and FnrP, control the switch between aerobic and anaerobic (denitrification) respiration. FnrP is a [4Fe–4S] cluster-containing homologue of the archetypal O2 sensor FNR from E. coli and accordingly regulates genes encoding aerobic and anaerobic respiratory enzymes in response to O2, and also NO, availability. Here we show that FnrP undergoes O2-driven [4Fe–4S] to [2Fe–2S] cluster conversion that involves up to 2 O2 per cluster, with significant oxidation of released cluster sulfide to sulfane observed at higher O2 concentrations. The rate of the cluster reaction was found to be ~sixfold lower than that of E. coli FNR, suggesting that FnrP can remain transcriptionally active under microaerobic conditions. This is consistent with a role for FnrP in activating expression of the high O2 affinity cytochrome c oxidase under microaerobic conditions. Cluster conversion resulted in dissociation of the transcriptionally active FnrP dimer into monomers. Therefore, along with E. coli FNR, FnrP belongs to the subset of FNR proteins in which cluster type is correlated with association state. Interestingly, two key charged residues, Arg140 and Asp154, that have been shown to play key roles in the monomer–dimer equilibrium in E. coli FNR are not conserved in FnrP, indicating that different protomer interactions are important for this equilibrium. Finally, the FnrP [4Fe–4S] cluster is shown to undergo reaction with multiple NO molecules, resulting in iron nitrosyl species and dissociation into monomers.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00775-015-1326-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Fumarate–nitrate reduction regulator, Gene regulation, Iron–sulfur cluster, Oxygen, Nitric oxide

Introduction

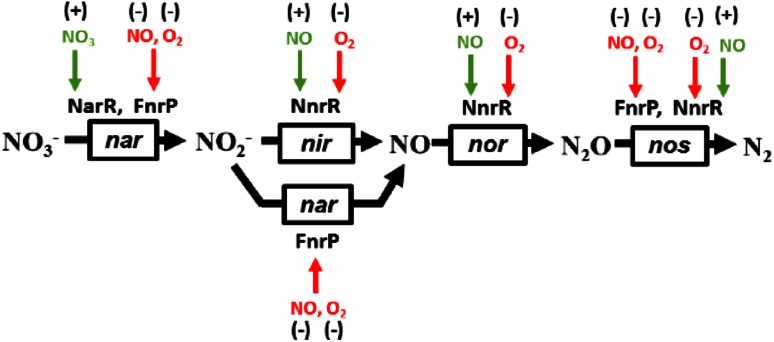

Paracoccus denitrificans is a popular model organism and one of the best studied prokaryotes with respect to respiration. It has a remarkable metabolic versatility allowing it to thrive in aerobic or anaerobic environments [1, 2]. Under anaerobic conditions nitrogen oxides can be utilized as terminal electron acceptors, in place of oxygen, and P. denitrificans is one of several organisms for which the denitrification pathway is well understood. It expresses four essential reductases which sequentially reduce nitrate (nar), nitrite (nir), nitric oxide (nor) and nitrous oxide (nos) to dinitrogen [3]. Optimal switching from aerobic respiration to the denitrification pathway is thus a key requirement for this flexibility, and the coordination of the denitrification enzymes is tightly controlled at the transcriptional level [4].

In E. coli, the fumarate and nitrate reduction (FNR) transcriptional regulator is responsible for sensing environmental levels of O2 and controlling the switch to anaerobic nitrate respiration [5]. FNR proteins represent a major sub-group of the cyclic-AMP receptor protein (CRP) family of bacterial transcriptional regulators, and, like CRP, consist of two distinct domains that provide DNA-binding and sensory functions [6–8]. However, unlike E. coli, some bacterial species possess multiple members of the FNR protein family [4, 9]; P. denitrificans has three major FNR paralogues which coordinate the regulation of the denitrification enzymes [4]. One of these paralogues, NarR, is a nitrate sensor involved in regulating nitrate reductase (nar) expression. The second, NnrR, is a heme-based nitric oxide sensor involved in the control of expression of nitrite (nir), nitric oxide (nor) and nitrous oxide reductases (nos) [4]. The third, FnrP, is a true orthologue of E. coli FNR as it regulates genes encoding aerobic and anaerobic respiratory enzymes in response to O2 availability [4, 10–12].

FnrP becomes activated under anaerobic conditions by the insertion of an O2-labile [4Fe–4S]2+ cluster, coordinated by four cysteine residues (Cys14, 17, 25 and 113) present in the N-terminal sensory domain [13]. Cluster incorporation enables the C-terminal DNA-binding domain to recognize specific binding sites located in FnrP regulated promoters. Inactivation of FnrP by O2 very likely involves oxidative disassembly of the [4Fe–4S] cluster, causing FnrP to adopt a transcriptionally inactive form [14]. In this way, FnrP regulates most of the genes associated with adaptation to the anaerobic environment, including nitrate reductase (nar) and nitrous oxide reductases (nos) [4, 10, 11], see Fig. 1. For E.coli FNR, exposure to O2 drives a [4Fe–4S]2+ to [2Fe–2S]2+ cluster conversion, causing the FNR dimer to dissociate into transcriptionally inactive monomers [5]. In contrast, FNR orthologues from P. putida (ANR) and B. subtilis (FnrB) both form a stable dimer under aerobic and anaerobic conditions, independent of the nature of the iron–sulfur cluster [9, 15].

Fig. 1.

Regulation of denitrification in P. denitrificans. Nitrate reductase (nar) is co-regulated by NarR and FnrP. Nitrite reductase (nir, and nitric oxide reductase (nor) are regulated solely by NnrR. Nitrous oxide reductase (nos) is co-regulated by FnrP and NnrR. Summarized from references [4, 10, 11, 14]. Small molecule effectors required to activate or inhibit transcription are marked a (+) or (−), respectively. Note: under certain circumstances nar will reduce nitrite (NO2 −) to nitric oxide (NO)

Many bacteria that carry out anaerobic respiration with nitrate/nitrite as a terminal electron acceptor can produce nitric oxide (NO) endogenously [16, 17]. In P. denitrificans, NO production represents a key intermediary step during reduction of nitrate to dinitrogen [3]. NO is a gaseous lipophilic radical that can function as both a signaling molecule and a cytotoxic agent [18]. The latter arises from the reactivity of NO with a variety of important cellular targets [19–21], including iron–sulfur cluster proteins [22]. Several regulatory proteins known to respond to NO contain iron–sulfur clusters as the sensory module [5, 23], and significant progress has been made recently in understanding the reactions of iron–sulfur clusters with NO in regulatory proteins [24, 25]. In the case of FnrP, there is growing in vivo evidence to suggest that, in addition to its primary function as an O2 sensor, it also plays a role in modulating gene expression in response to NO [10] in a similar way to E. coli FNR [25, 26].

Here we report investigations of the biochemical properties of FnrP. We present information on the nature of the iron–sulfur cluster, its reaction with O2 and NO, as well as the effect of these reactions on its association state. We compare our findings to those reported for E. coli FNR as well other FNR orthologues.

Materials and methods

Purification of FnrP

A GST-FnrP fusion protein (Fig. S1) was overproduced in aerobically grown E. coli BL21λDE3 harboring pSAD105, induced by the addition of 1 mM IPTG at 37 °C, as previously described [14]. For the in vivo assembly of [4Fe–4S] FnrP, the aeration of cultures harboring pSAD105 was reduced after induction, as previously described [27] to mimic semi-aerobic conditions [11]. FnrP was purified under anaerobic conditions using assay buffer (25 mM HEPES, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 100 mM NaNO3, pH 7.5) as previously described for E. coli FNR [28]. FnrP was cleaved from the fusion protein using thrombin (Fig. S1), and, where necessary, the [4Fe–4S] cluster reconstituted, in vitro, as previously described [14, 27, 29], except that a 1 ml Q Sepharose column was used to concentrate the protein and assay buffer containing 500 mM KCl was used to elute the protein. Protein concentration was determined using the method of Bradford (BioRad), with bovine serum albumin as the standard [30]. FnrP iron and acid-labile sulfide content were determined as previously described [31, 32].

Spectroscopy

UV–visible absorbance measurements were made with a Jasco V550 spectrometer. The extinction coefficient for the E. coli [4Fe–4S] FNR (ε406 nm = 16,200 M−1 cm−1 [28]) was used to calculate the amount of [4Fe–4S] cluster present in FnrP samples. CD spectra were measured with a Jasco J810 spectropolarimeter. For liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) an aliquot of FnrP (100 μL, 46 μM [4Fe–4S]) was combined with varying aliquots of aerobic (229 μM O2, 20 °C) or anaerobic assay buffer (200 μl final volume), and allowed to react for 15 min. Samples were diluted to ~2 μM final concentration, with an aqueous mixture of 1 % (v/v) acetonitrile, 0.3 % (v/v) formic acid, sealed, removed from the anaerobic cabinet and analyzed by an LC–MS instrument consisting of an Ultimate 3000 UHLPC system (Dionex, Leeds, UK), a ProSwift RP-1S column (4.6 × 50 mm) (Thermo Scientific), and a Bruker microQTOF-QIII mass spectrometer, running Hystar (Bruker Daltonics, Coventry, UK), as previously described [9].

Gel filtration

FnrP samples (loaded at ~28 μM [4Fe–4S]) before and after exposure to O2 were analyzed by gel filtration under anaerobic conditions using assay buffer and a calibrated Sephacryl S-100HR 16/50 column (GE Healthcare), at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1.

Kinetic measurements

Kinetic measurements were performed under pseudo-first-order conditions (162 μM O2) at 25 °C by combining varying ratios of aerobic and anaerobic assay buffer (2 ml total volume) with FnrP (8.5 μM [4Fe–4S]). Changes in A406 nm were used to track cluster conversion. A single or double exponential function, as necessary, was fitted to the data, as previously described [9, 28, 33]. Observed rate constants (kobs) obtained from the fits (in the case of double exponential fits, the rate constant for the first reaction phase was used) were divided by the O2 concentration, providing an estimate of the apparent second-order rate constant. Kinetic data fitting was performed using Origin (version 8, Origin Labs). Estimates of errors for rate constants are represented as ±the standard deviation.

Other analytical methods

FnrP (2 ml) was titrated against varying aliquots of O2 (~220 μM dissolved in assay buffer) or NO (as NONOate; Cayman chemicals), using anaerobic cuvettes and gas tight syringes. Stock solutions of the NO donor PROLI-NONOate (t½ = 1.5 s) were prepared in 50 mM NaOH and quantified optically (ε252 nm 8400 M−1 cm−1).

Results and discussion

In vivo purified and in vitro reconstituted FnrP binds an identical [4Fe–4S] cluster

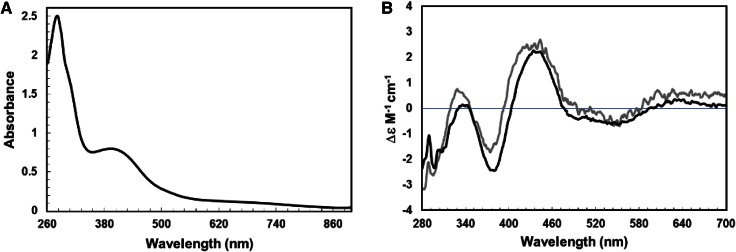

Cluster reconstitution of apo-FnrP yielded a straw brown-colored solution with a UV-visible absorbance spectrum (see Fig. 2a) containing a broad shoulder at 420 nm, together with a less well-resolved feature at ~310 nm, indicative of the presence of a [4Fe–4S] cluster, as previously described [14]. A cluster-containing form of FnrP was also expressed in E. coli cultures (hereafter referred to as native) and isolated under anaerobic conditions. Reconstituted FnrP samples used in this work contained 0.9 (±0.1) clusters per monomer, based on absorbance measurements, and protein, iron, and acid-labile sulfide determinations. Native samples were found to contain variable amount of the [4Fe–4S] cluster, up to a maximum of ~0.7 per monomer.

Fig. 2.

Spectroscopic properties of [4Fe–4S] FnrP. a. Absorbance spectrum of reconstituted FnrP (48 μM [4Fe–4S], 81 % cluster loaded), b CD spectrum of the same reconstituted FnrP (black) and [4Fe–4S] FnrP assembled in vivo (gray), for comparison. The buffer was 25 mM HEPES 2.5 mM CaCl2 100 mM NaCl 100 mM NaNO3, 500 mM KCl, pH 7.5

As FnrP contains seven cysteine residues (Cys8, 14, 17, 25, 28, 113 and 144), it is possible that differing methods (in vitro versus in vivo) of iron–sulfur cluster assembly might lead to significant differences in the ligation pattern and hence the local environment of the cluster. Since iron–sulfur clusters derive their optical activity from the fold of the protein to which they are ligated, the CD spectrum provides information about the cluster environment. The anaerobic CD spectra of both native and reconstituted [4Fe–4S] FnrP displays positive (+) features at 335 and 440 nm, together with negative (−) features at 300, 375, and 520 nm (see Fig. 2b). The Δε values for the native and reconstituted forms of FnrP are very similar, indicating that the [4Fe–4S] clusters are in essentially identical environments. Hence, reconstituted FnrP was used in subsequent experiments.

Interestingly, the shape of the CD spectrum of FnrP is quite distinct from that of E. coli FNR [28]. The major bands at (−)375 nm and (+)440 nm, in FnrP, which originate primarily from S → Fe charge transitions, are equivalent to bands observed at (+)380 nm and (+)420 nm for [4Fe–4S] FNR and other [4Fe–4S] containing proteins, such as HiPIP, WhiD and ANR [9, 34, 35]. However, there is no strict correlation between the cluster type and the shape or sign of bands in the CD spectrum; presumably, differences in the cluster binding cavity and/or the geometry of the cluster lead to variation in the CD spectrum.

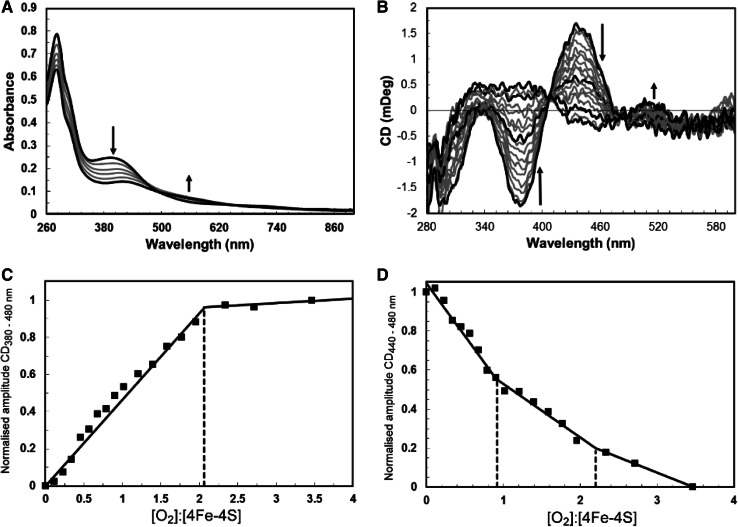

Reaction of [4Fe–4S] FnrP with O2 resembles that of E. coli FNR

Titration of reconstituted FnrP with aerobic buffer (229 μM dissolved O2 at 20 °C) revealed a progressive decrease in A406 nm and concomitant increase at 530 nm (see Fig. 3a), features typically associated with an FNR-like [4Fe–4S] to [2Fe–2S] conversion [5, 36]. Clear end points to the titration were not observed at A406 nm, possibly due to the slow degradation of the [2Fe–2S] cluster, which contributes to the ΔA406 nm readings. Therefore, an identical titration was followed by CD spectroscopy (see Fig. 3b). The well-resolved features of the [4Fe–4S] cluster were gradually replaced with a broad spectrum reminiscent of E. coli [2Fe–2S] FNR, containing positive features at ~360 and ~510 nm, together with a single negative feature at ~450 nm, and isosbestic points at 408 and 480 nm. The spectral features of native [4Fe–4S] FnrP behaved in a comparable manner (not shown) during equivalent titrations. A plot of CD380 nm–CD480 nm versus [O2]:[4Fe–4S] (Fig. 3c) revealed that the reaction reached completion at an [O2]:[4Fe–4S] ratio of ~2; this behavior is notably different to that of E. coli FNR [36], which showed that the reaction was 85 % complete at a ratio of 1 [O2]:[4Fe–4S]. By contrast, plotting CD440 nm–CD480 nm versus [O2]:[4Fe–4S] revealed clear inflection points at both 1 and 2 [O2]:[4Fe–4S] cluster (see Fig. 3d), suggesting the presence of a meta-stable intermediate.

Fig. 3.

Titration of [4Fe–4S] FnrP with oxygen. a Absorbance spectra following addition of O2 to [4Fe–4S] FnrP (15 μM in cluster). Black lines represent an [O2]:[4Fe–4S] ratio of 0 and 5, respectively. b CD spectra following addition of O2 to [4Fe–4S] FnrP (16 μM in cluster) monitored by circular dichroism. Black lines represent [O2]:[4Fe–4S] ratios of 0, 1, 2 and 3.5, respectively. Arrows indicate the direction of movement in response to O2. Spectra recorded at intervening [O2]:[4Fe–4S] ratios are shown in gray. c CD380–480 nm and d CD440–480 nm values were normalized and plotted versus the [O2]:[4Fe–4S] ratio

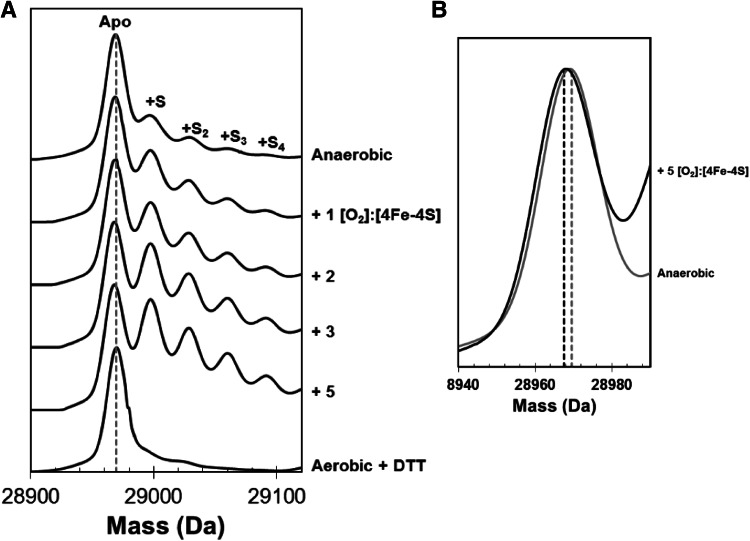

Analysis of iron–sulfur proteins via liquid chromatography–mass spectroscopy (LC–MS) invariably leads to the loss of the cluster, although previous studies have shown that cysteine persulfides formed during the reaction of the cluster with O2 remain intact [37]. It was, therefore, of interest to determine if O2-mediated cluster conversion in FnrP resulted in retention of cluster sulfides as covalent adducts. [4Fe–4S] FnrP was treated with increasing amounts of O2 (up to 5 molar equivalents) for 15 min, and analyzed by LC–MS, see Fig. 4a. Even prior to the introduction of O2, a small amount of sulfur adduct (at +32 Da of the 28,969 Da peak) was observed. As O2 was introduced, the relative abundance of these adducts increased, with 1–4 persulfide adducts observed and with the single persulfide adduct at +32 Da the most abundant. Furthermore, the mass of the main protein peak decreased by 1–2 Da, indicating formation of disulfide bonds (Fig. 4b). Treatment with 2 mM DTT, post-O2 exposure, resulted in the loss of all sulfur adducts and reduction of disulfides.

Fig. 4.

Detection of persulfide species of FnrP by LC–MS. a ESI-TOF mass spectra of [4Fe–4S] FnrP (2.3 μM) before and after the addition of increasing amounts of O2 are shown, as indicated. The peak at 28,969 Da corresponds to the monomer molecular ion peak of FnrP, and the peaks at +32, +64, +96 and +128 Da correspond to the addition of one, two, three and four covalently bound sulfur atoms, respectively, as indicated. Treatment of an aerobic ([O2]:[4Fe–4S] = 5) sample, post-O2 exposure, with DTT led to loss of persulfide adducts. b During the titration, the mass of the FnrP decreased from 28,969 to 28,967 Da, corresponding to the loss of 2 protons and indicative of O2-induced disulfide bond formation

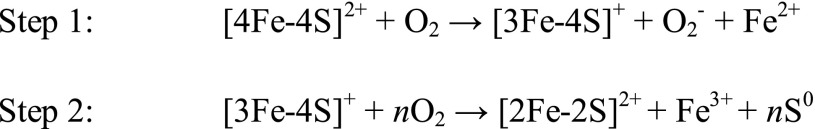

The [4Fe–4S] cluster of E. coli FNR has been shown to react with O2 via a two-step mechanism (see Scheme 1). Step 1 involves the one electron oxidation of the [4Fe–4S]2+ cluster leading to release of Fe2+ to generate a [3Fe–4S]1+ intermediate along with superoxide, which may be recycled back to O2 by the combined actions of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase [33]. Step 2 involves the conversion of the [3Fe–4S]+ cluster to the [2Fe–2S]2+ cluster, with the concomitant release of a further iron ion and oxidation of cluster sulfides, which can be stored as cysteine persulfide [5, 33, 37]. In the case of FnrP, the two inflection points observed in the CD intensity plot (Fig. 3d) together with the LC–MS data (Fig. 4) indicate that the availability of O2 beyond a ratio of 1 per cluster results in increased sulfide oxidation/persulfide formation. This, causes further changes in the CD spectrum, up to a ratio of 2 [O2]:[4Fe–4S], with little further effect beyond this, suggesting that persulfidation of cluster-coordinating Cys residues occurs mostly in the 1–2 [O2]:[4Fe–4S] range.

Scheme 1.

Reaction of E. coli [4Fe-4S] FNR with O2

FnrP reacts more slowly than E. coli FNR with O2 in vitro

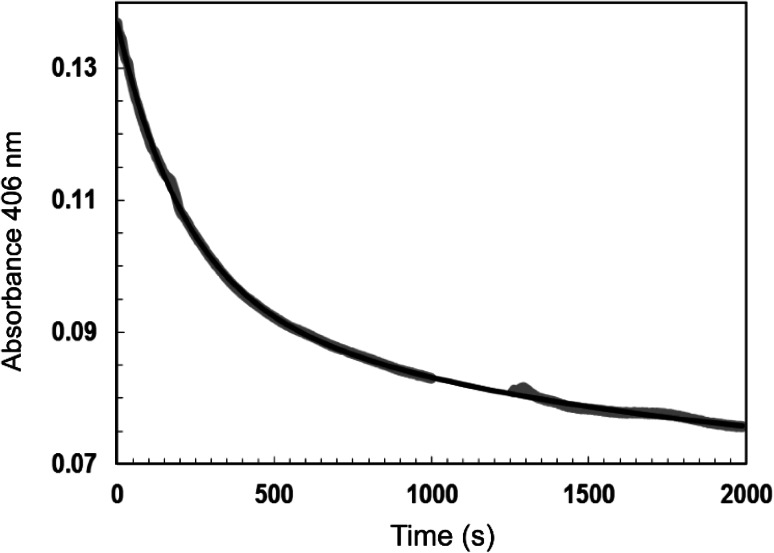

The first clue that [4Fe–4S] FnrP may be less sensitive to O2 was the isolation of a straw brown protein from semi-aerobic cultures. Equivalent preparations with E. coli FNR typically yield apo-FNR or occasionally [2Fe–2S] FNR [38, 39]; anaerobic cultures are required to obtain [4Fe–4S] FNR [27, 40]. Hence, it was of interest to investigate the kinetics of O2-induced [4Fe–4S] FnrP cluster conversion. The A406 nm decay for FnrP was measured under pseudo-first-order reaction conditions ([O2]:[4Fe–4S] ratio of ~19). The data were fitted best by a double exponential function (consistent with a two-step reaction [33]) with an observed rate constant (kobs) for the first reaction of 0.0047 (±0.0001) s−1 (see Fig. 5). Division of kobs by the O2 concentration (161 μM) provides an estimate of the apparent second-order rate constant, k = 29 (±1) M−1 s−1. This value establishes that the [4Fe–4S] cluster of FnrP is significantly less reactive with O2 in vitro than the archetypal E. coli FNR cluster [28], and that it more closely resembles the Pseudomonas putida FNR proteins PP_3233 and PP_3287 and the previously characterized variant of E.coli FNR, FNR-S24F, in its reactivity (see Table 1) [9, 41].

Fig. 5.

Kinetics of O2-mediated [4Fe–4S] cluster conversion. Kinetics were recorded under pseudo-first-order conditions (8.5 μM [4Fe–4S], 161.6 μM O2) at an [O2]:[4Fe–4S] ratio of 19 at 25 °C. A double exponential function (black line) was used to fit the data (gray). The rate constants reported in the text from these experiments are mean values with standard errors from two repeats

Table 1.

Kinetic data for the reaction of FNR homologues with O2

Previous work with E. coli FNR showed that replacement of Ser24, located immediately adjacent to the cluster ligand Cys23, by Pro results in significant aerobic FNR activity, indicative of FeS cluster stabilization [41]. Interestingly, FnrP has Pro in the position equivalent to Ser24 in FNR (Fig. 6a). Thus, this amino acid residue substitution could, at least partially, account for the lower O2 reactivity. We note that amino acid substitutions at other positions next to cluster-coordinating Cys residues are also known to influence the aerobic reactivity of the E. coli FNR cluster with O2. For example, substitutions of Asp22 with Ser or Gly resulted in increased activity under aerobic conditions [42, 43]. The equivalent position in FnrP is occupied by Ile (Fig. 6a) and this difference likely alters the redox properties of the cluster, resulting in a lower reactivity towards O2.

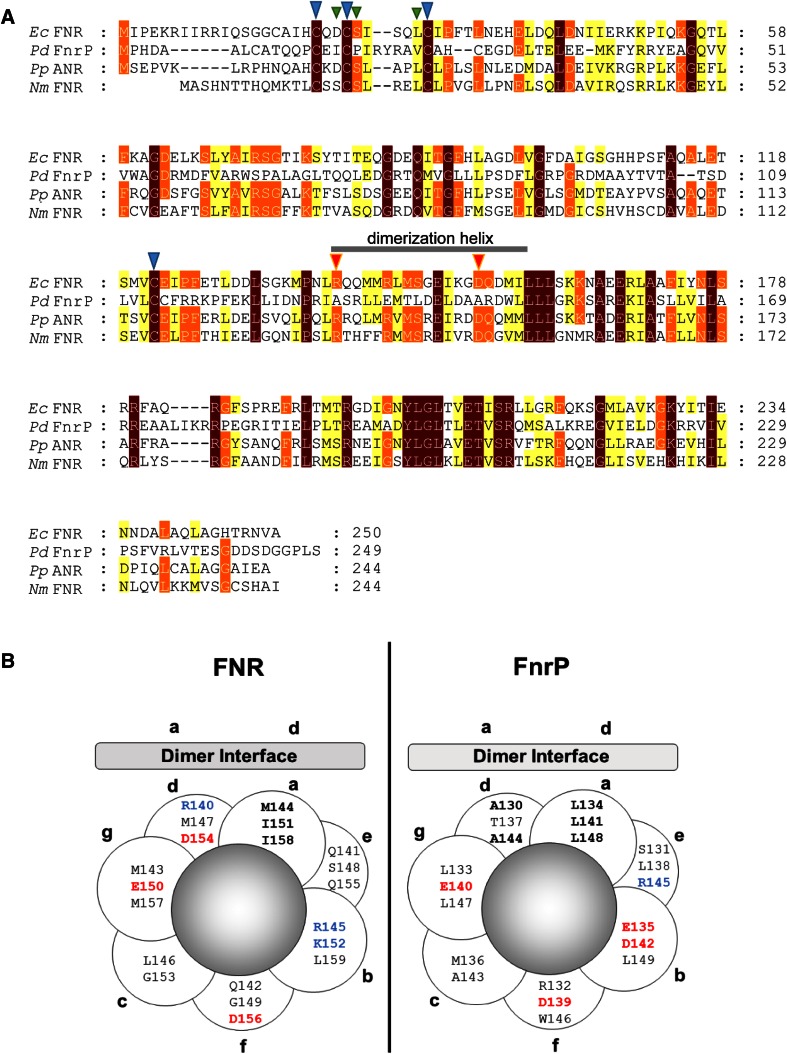

Fig. 6.

Sequence alignments of FNR proteins and comparison of the dimerization helixes of FNR and FnrP. a Sequence alignment of FNR proteins. The dimerization helix is indicated. Cluster-coordinating residues are indicated by blue arrowheads. Residues next to cluster-coordinating Cys residues that are important for controlling cluster reactivity are indicated by green arrowheads. Two key residues within the helix that are important for E. coli FNR association state, Arg140 and Asp154, are indicated by orange arrowheads. Proteins are E. coli FNR (EcFNR), Paracoccus denitrificans FnrP (PdFnrP), Pseudomonas aeruginosa FNR (PaNnrR) and Neisseria meningitidis FNR (NmCRP). The alignment was generated using Clustal Omega [53] and annotated using Genedoc [54]. b Helical wheel projection of the dimerization helix of a E. coli FNR and b P. denitrificans FnrP, assuming the standard 3.5 residues per turn for a coiled coil. Residues that when substituted by alanine result in a significantly altered activity in E. coli FNR, and predicted equivalents in FnrP, occupy positions a and d of the helical wheel. Adapted from Moore et al. [46]

Under O2-limiting conditions many bacteria induce high-affinity oxidases, as the ATP yield from oxygen respiration is significantly higher than anaerobic respiration [2]. P. denitrificans is no different in this respect, with FnrP activating the expression of the cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase (cco) in vivo [2, 11]. We note that cco promoter activity increases by eight times during the switch from aerobic to semi-aerobic growth conditions [11]. In contrast, the high-affinity E. coli cytochrome bd-I (cydAB) oxidase (a quinol:O2 oxidoreductase) is repressed by [4Fe–4S] FNR under anaerobic conditions [44, 45]. Thus, P. denitrificans may begin to utilize its high-affinity oxidases at significantly higher environmental O2 concentrations than its rivals to gain a competitive advantage.

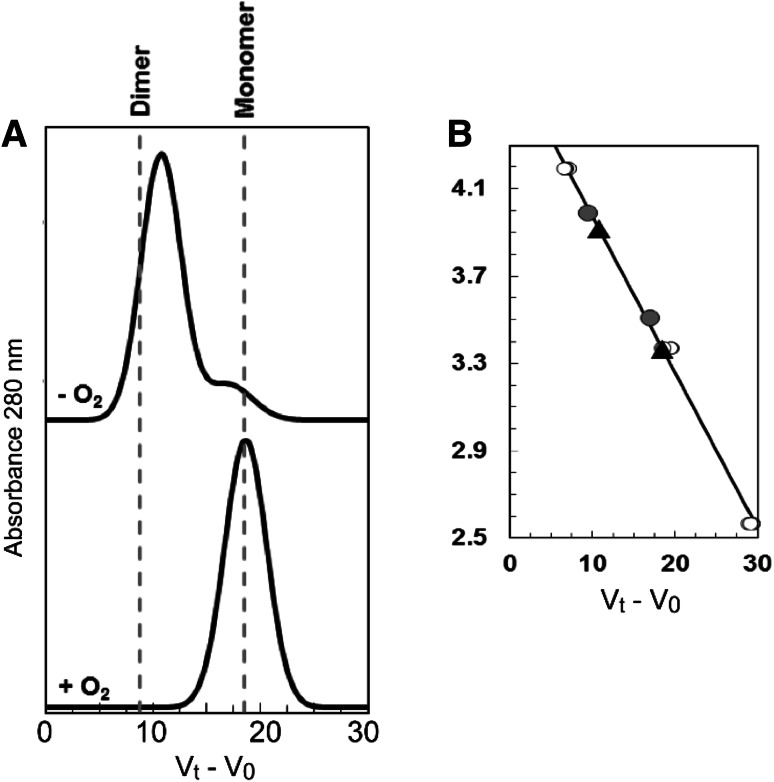

The oligomeric state of FnrP is dependent on the [4Fe–4S] cluster

Under anaerobic conditions E. coli FNR acquires a [4Fe–4S] cluster, triggering a conformational change at the dimerization interface that leads to the formation of homo-dimers (~60 kDa) and site-specific DNA binding [5]. Upon exposure to O2, a [4Fe–4S] to [2Fe–2S] cluster conversion results in a rearrangement of the dimer interface, leading to monomerization (~30 kDa) [46]. To date, only E. coli FNR has been reported to undergo this monomer/dimer transition; with other FNR orthologues tending to remain dimeric irrespective of the cluster [9, 15]. Therefore, the oligomeric state of reconstituted [4Fe–4S] FnrP (~90 % loaded) was examined by analytical gel filtration (see Fig. 7). FnrP has a mass of ~29 kDa, per monomer. In the absence of O2, the majority of the protein eluted with a relative molecular mass of 51.0 (±1.0) kDa, somewhat lower than, but close to, the expected mass for a homodimer. We note that a slight shoulder, corresponding to a relative molecular mass of ~32 kDa, was also observed. In the presence of O2, the protein eluted with a relative molecular mass of 28.8 (±0.2) kDa, as expected for monomeric FnrP. These results indicate that cluster conversion drives a rearrangement of the dimer interface, leading to monomerization, as observed for E. coli FNR.

Fig. 7.

Association state properties of FnrP probed by gel filtration. a Chromatogram for reconstituted [4Fe–4S] FnrP in the absence (upper trace) or presence of O2 (lower trace). In the absence of O2 FnrP had an apparent molecular mass of ~51 kDa, indicative of a dimer. A small shoulder, corresponding to a mass of ~32 kDa (monomer) is also observed. In the presence of O2, FnrP had an apparent mass of ~29 kDa, consistent with monomeric protein. b Standard calibration curve for a Sephacryl S100HR column. Open circles correspond to standard proteins (BSA, carbonic anhydrase, cytochrome c), gray circles correspond to the two states of E. coli FNR. Black triangles correspond to the two states of FnrP. Ln M w, natural log of molecular weight in kDa

Moore and Kiley [46] showed that subunit interactions in E. coli FNR arise from a predominantly hydrophobic interface (see Fig. 6b), and that the negatively charged side chain of Asp154 is oriented towards this interface, where inter-subunit charge repulsion inhibits dimerization before cluster acquisition. Insertion of the [4Fe–4S]2+ cluster apparently causes shielding of the negative charge, by Ile-151, thereby facilitating dimerization. The recent structure of the E. coli FNR-like FNR from Aliivibrio fischeri [47] was broadly in agreement with this model, but indicated that hydrophobic contacts made between Ile-151 residues of the two subunits, rather than screening electrostatic repulsion, is key to stabilizing the dimer. Removal of the negatively charged side chain by substitution, such as in FNR-D154A, alleviates the repulsion even in the absence of a cluster, leading to a predominantly dimeric form whether the cluster is present or not. The positive charge of Arg140 is also important for FNR function. Substitution of this positively charged side chain, such as in FNR-R140A, resulted in an FNR variant with little anaerobic activity, implying a defect in dimerization. In the A. fischeri FNR structure, Arg-140 is located near the N terminus of the dimerization helix where no dimerization helix interactions occur. Instead, the Arg-140 sidechain forms a salt bridge with Asp-130 of the other subunit (B helix) and it was suggested that this interaction plays a key role in dimer stability. Interestingly, the double mutant FNR-R140A/D154A regained ≥70 % activity under anaerobic conditions [46]. Assuming residues 130 to 149 participate in subunit interactions, analogous to E. coli FNR residues 140 to 159 (Fig. 6a), then Leu134, 141 and 148 presumably form the core of the hydrophobic interface in FnrP (see Fig. 6b). Moreover, charged residues Arg140 and Asp154, found to be important to the monomer/dimer equilibrium in E. coli FNR, appear to be replaced by Ala130 and Ala144 in FnrP. Thus, the ability of FnrP to undergo a cluster-induced monomer/dimer transition may depend on the lack of strong electrostatic interactions involving the side chains of Ala130 and Ala144 (cf the E. coli FNR variant R140A/D154A [46]). The remainder of the residues in FnrP appears to preserve the general nature of the E. coli FNR dimerization helix (see Fig. 6). We note that Bradyrhizobium japonicum FixK2 also contains Ala residues at equivalent positions to FnrP Ala130 and 144, and that other CRP/FNR family paralogues tend to contain an Ala residue in place of the Arg residue and a hydrophobic/non-charged residue in place of the negatively charged Asp residue (see Fig. S2).

FnrP is a nitric oxide (NO) sensor

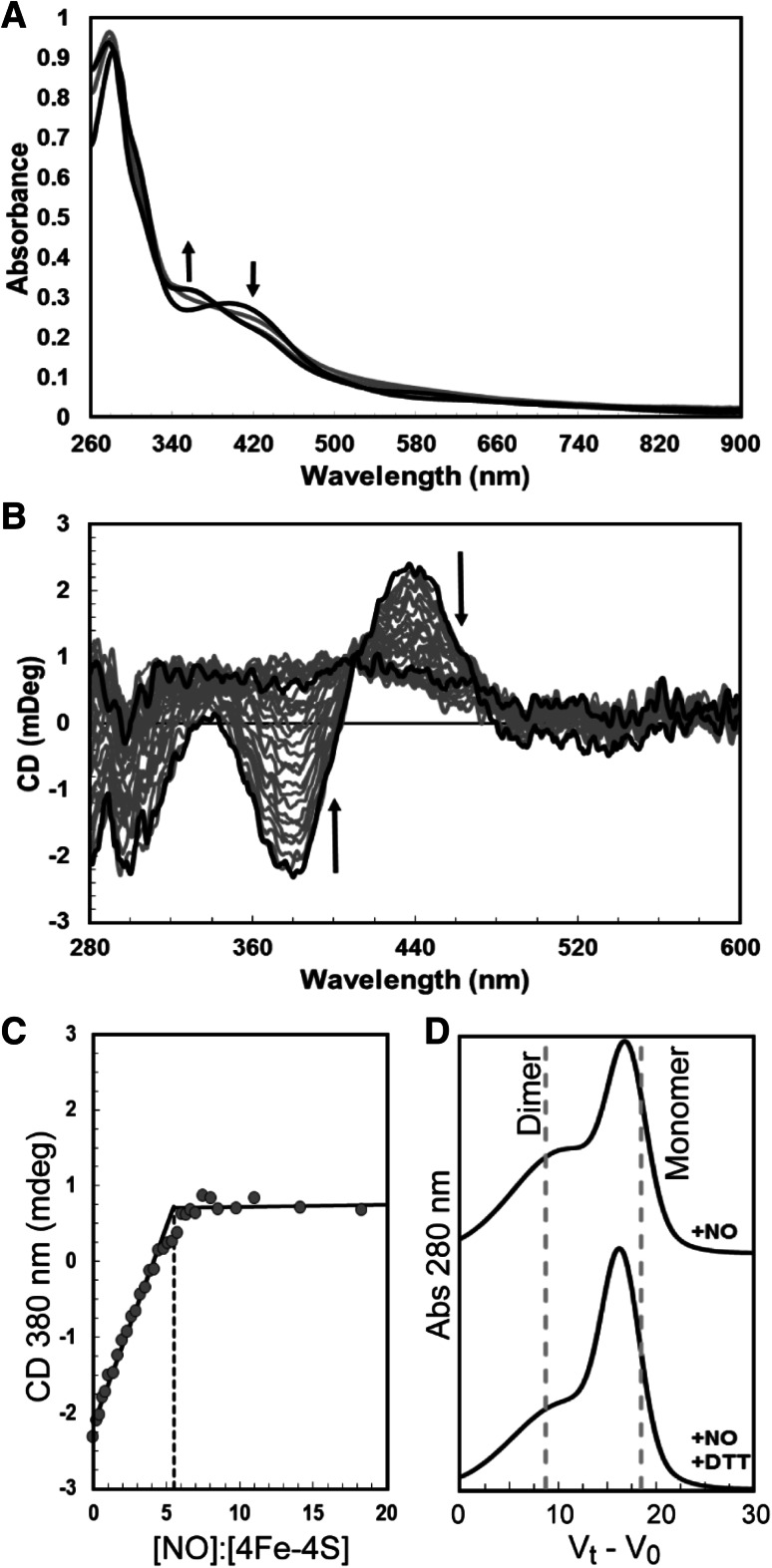

In P. denitrificans at least three FNR-like transcriptional regulators are involved in the regulation of the four denitrification reductases (see Fig. 1), in response to nitrate, NO or O2 [4]. In vivo studies have shown that FnrP is involved in the dual control of both the nitrate reductase (nar) and the nitrous oxide reductase (nos) with NarR and NnrR, respectively, and that factors besides O2 influence the activity of FnrP [10, 12, 48]. In this respect, we note that the cco promoter activity drops to one-third of the semi-aerobic level when cultures are shifted from semi-aerobic to denitrifying conditions and that cultures experience a transitory accumulation of NO under anaerobic conditions prior to the establishment of denitrification. There is also increasing evidence to suggest that FnrP, like E. coli FNR, also responds to NO in vivo [10, 11]. Therefore, we investigated the stoichiometry of the reaction of the FnrP cluster with NO by measuring changes in CD and absorbance spectral properties following sequential additions of NO to anaerobic FnrP. A progressive decrease in A406 nm and an increase in A360 nm was observed. The final UV–visible spectrum, with a principal absorption band at 360 nm and a shoulder at 430 nm are consistent with previous observations of reaction of an iron–sulfur cluster with NO and indicate the formation of iron–nitrosyl species (see Fig. 8a) [24, 25]. CD signals arising from the [4Fe–4S] cluster decreased almost to zero as the reaction with NO proceeded (Fig. 8b). A plot of intensity at 380 or 430 nm versus [NO]:[4Fe–4S] (Fig. 8C) revealed that the reaction was complete at a stoichiometry of ≥7 NO molecules per cluster, with a clear inflection point at ~6 NO, similar to the previously reported nitrosylation of E. coli FNR [25].

Fig. 8.

Titration of [4Fe–4S] FnrP with NO. a Absorbance spectra of [4Fe–4S] FnrP (18 μM [4Fe–4S]) following exposure to NO. After each addition of Proli-NONOate, the sample was incubated at an ambient temperature for 5 min prior to spectroscopic measurements. Black lines correspond to [NO]:[4Fe–4S] ratios of 0 and 18. Intervening spectra (gray lines) correspond to ratios of 4 and 8. b CD spectra of an equivalent titration (18 μM [4Fe–4S]). Black lines correspond to [NO]:[4Fe–4S] ratios of 0 and 18, intervening spectra are gray. c CD380 nm values were normalized and plotted versus the [NO]:[4Fe–4S] ratio. d Gel filtration analysis of nitrosylated FnrP. In the presence of NO, FnrP had a molecular mass of ~33 kDa (monomer). A broad shoulder, corresponding to a mass of 50–100 kDa, was also observed. The shape of this shoulder decreased in the presence of DTT, implying that it may arise from a disulfide-bonded FnrP aggregate

Analysis by gel filtration of molecular mass changes upon nitrosylation of [4Fe–4S] FnrP revealed a decrease in mass from 51 to 33 kDa (Fig. 8d) for the bulk of the sample. A broad shoulder, corresponding to a mass of ~50–100 kDa, was also observed. The shoulder decreased following treatment with DTT, implying that a small proportion of the sample was in the form of a disulfide-bonded FnrP aggregate. Moreover, LC–MS analysis of nitrosylated FnrP revealed the presence of sulfur adducts (not shown), as previously observed for E. coli FNR [25]. We conclude that nitrosylation of FnrP is likely to proceed in a manner similar to that previously reported for E. coli FNR, and that, like its reaction with O2, nitrosylation of FnrP results in dissociation of the dimer into monomers, again similar to E. coli FNR.

Conclusion

FNR proteins are global transcription factors that respond to changes in environmental O2 through the assembly and disassembly of an O2-sensitive [4Fe–4S] cluster. In the archetypal FNR protein E. coli FNR, molecular O2 brings about conversion of the [4Fe–4S] cluster into a [2Fe–2S] form, thereby triggering conformational changes that initiate monomerization and concomitant loss of sequence-specific DNA binding. In this respect, the P. denitrificans regulator FnrP is similar to its E. coli counterpart [5]. However, sequence alignment revealed that the residues important for the monomer–dimer equilibrium for FnrP are different to those in E. coli FNR and involve fewer charged side chain interactions. Furthermore, we have found that the FnrP cluster is at least 6 times less sensitive to O2 than E. coli FNR. This finding is consistent with the observation of FnrP-activated expression of cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase, nitrate reductase and nitrous oxide reductase under semi-aerobic conditions in vivo [11, 48].

Many transcriptional regulators are known to respond to NO and in P. denitrificans the principal regulators are NsrR, NnrR, and FnrP. In other bacterial species NsrR regulates, amongst others, genes involved in detoxification, such as hmp, for which NO is a substrate [49, 50]. NnrR principally activates the expression of the nitrite, nitric oxide, and nitrous oxide reductases under anaerobic conditions in response to NO, thereby facilitating denitrification [13, 51, 52]. With regard to denitrification, FnrP co-regulates the expression of the nitrate and nitrous oxide reductases, ensuring their production under semi-aerobic conditions. We note that nitrate reductase is the most important source of endogenously derived NO during nitrate/nitrite respiration [16]. It is suggested that if the NO detoxification systems are overwhelmed, FnrP will become nitrosylated leading to lowered expression of cco, and modulation of the nar and nos operons (that require [4Fe–4S] FnrP for activation). The concomitant detection of NO by NnrR would then ensure the timely expression of the nir, nor and nos operons, minimizing the transitory nitrosative stress as metabolic modes are switched over in favor of denitrification. Fig. S3 shows a summary of these regulatory systems. Here we have shown that [4Fe–4S] FnrP undergoes a nitrosylation reaction involving multiple NO molecules. This leads to dissociation of FnrP, containing iron–nitrosyl products similar to those observed for other NO-sensing iron–sulfur regulatory proteins, into monomers, providing a mechanistic basis for NO regulation of FnrP.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the UK’s Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council grant BB/L007673/1 to NLB, AJT and JCC. We thank Nick Cull for technical assistance, Dr. Myles Cheesman for access to instrumentation and Prof. Stephen Spiro for pSAD105 encoding GST-FnrP.

Abbreviations

- DTT

Dithiothreitol

- GST

Glutathione S-transferase

- FNR

Fumarate nitrate reduction

- HEPES

4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazine-ethanesulfonic acid

- IPTG

Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside

- LC–MS

Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

- NO

Nitric oxide

- PROLI-NONOate

1-(Hydroxy-NNO-azoxy)-l-proline, disodium salt

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

Compliance with ethical standards

Dedication

The authors dedicate this article to the memory of Bob Williams. They have been strongly influenced by his scientific work and inspired by his spirit. Andrew Thomson and Geoff Moore (see accompanying article on ferritins) studied in Oxford with Bob for their doctoral degrees. At UEA, together with the late Colin Greenwood, they established a multi-disciplinary research unit, the Centre for Metalloprotein Spectroscopy and Biology (CMSB). Nick Le Brun and Jason Crack carried out their doctoral studies in the CMSB under the supervision of Andrew and Geoff. Bob was an adviser to, and a strong supporter of, the CMSB.

Contributor Information

Jason C. Crack, Email: j.crack@uea.ac.uk

Nick E. Le Brun, Email: n.le-brun@uea.ac.uk

References

- 1.Bakken LR, Bergaust L, Liu B, Frostegard A. Regulation of denitrification at the cellular level: a clue to the understanding of N2O emissions from soils. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012;367:1226–1234. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson DJ. Bacterial respiration: a flexible process for a changing environment. Microbiology. 2000;146:551–571. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-3-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zumft WG. Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:533–616. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.4.533-616.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veldman R, Reijnders WN, van Spanning RJ. Specificity of FNR-type regulators in Paracoccus denitrificans. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:94–96. doi: 10.1042/BST0340094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crack JC, Green J, Thomson AJ, Le Brun NE. Iron-sulfur clusters as biological sensors: the chemistry of reactions with molecular oxygen and nitric oxide. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:3196–3205. doi: 10.1021/ar5002507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green J, Scott C, Guest JR. Functional versatility in the CRP-FNR superfamily of transcription factors: fNR and FLP. Adv Microb Physiol. 2001;44:1–34. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(01)44010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsui M, Tomita M, Kanai A. Comprehensive computational analysis of bacterial CRP/FNR superfamily and its target motifs reveals stepwise evolution of transcriptional networks. Genome Biol Evol. 2013;5:267–282. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw DJ, Rice DW, Guest JR. Homology between CAP and Fnr, a regulator of anaerobic respiration in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:241–247. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(83)80011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ibrahim SA, Crack JC, Rolfe MD, Borrero-de Acuna JM, Thomson AJ, Le Brun NE, Schobert M, Stapleton MR, Green J. Three Pseudomonas putida FNR family proteins with different sensitivities to O2. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:16812–16823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.654079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergaust L, van Spanning RJ, Frostegard A, Bakken LR. Expression of nitrous oxide reductase in Paracoccus denitrificans is regulated by oxygen and nitric oxide through FnrP and NNR. Microbiology. 2012;158:826–834. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.054148-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otten MF, Stork DM, Reijnders WN, Westerhoff HV, Van Spanning RJ. Regulation of expression of terminal oxidases in Paracoccus denitrificans. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:2486–2497. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Spanning RJ, De Boer AP, Reijnders WN, Westerhoff HV, Stouthamer AH, Van Der Oost J. FnrP and NNR of Paracoccus denitrificans are both members of the FNR family of transcriptional activators but have distinct roles in respiratory adaptation in response to oxygen limitation. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:893–907. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2801638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hutchings MI, Spiro S. The nitric oxide regulated nor promoter of Paracoccus denitrificans. Microbiology. 2000;146:2635–2641. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-10-2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutchings MI, Crack JC, Shearer N, Thompson BJ, Thomson AJ, Spiro S. Transcription factor FnrP from Paracoccus denitrificans contains an iron-sulfur cluster and is activated by anoxia: identification of essential cysteine residues. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:503–508. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.2.503-508.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reents H, Gruner I, Harmening U, Bottger LH, Layer G, Heathcote P, Trautwein AX, Jahn D, Hartig E. Bacillus subtilis Fnr senses oxygen via a [4Fe–4S] cluster coordinated by three cysteine residues without change in the oligomeric state. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:1432–1445. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ralt D, Wishnok JS, Fitts R, Tannenbaum SR. Bacterial catalysis of nitrosation: involvement of the nar operon of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:359–364. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.1.359-364.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watmough NJ, Butland G, Cheesman MR, Moir JW, Richardson DJ, Spiro S. Nitric oxide in bacteria: synthesis and consumption. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1411:456–474. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(99)00032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruckdorfer R. The basics about nitric oxide. Mol Aspects Med. 2005;26:3–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Broillet MC. S-nitrosylation of proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:1036–1042. doi: 10.1007/s000180050354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon YM, Weiss B. Production of 3-nitrosoindole derivatives by Escherichia coli during anaerobic growth. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:5369–5376. doi: 10.1128/JB.00586-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiss B. Evidence for mutagenesis by nitric oxide during nitrate metabolism in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:829–833. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.3.829-833.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drapier JC. Interplay between NO and [Fe-S] clusters: relevance to biological systems. Methods. 1997;11:319–329. doi: 10.1006/meth.1996.0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fleischhacker AS, Kiley PJ. Iron-containing transcription factors and their roles as sensors. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2011;15:335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crack JC, Smith LJ, Stapleton MR, Peck J, Watmough NJ, Buttner MJ, Buxton RS, Green J, Oganesyan VS, Thomson AJ, Le Brun NE. Mechanistic insight into the nitrosylation of the [4Fe–4S] cluster of WhiB-like proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1112–1121. doi: 10.1021/ja109581t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crack JC, Stapleton MR, Green J, Thomson AJ, Le Brun NE. Mechanism of [4Fe–4S](Cys)4 cluster nitrosylation is conserved amongst NO-responsive regulators. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:11492–11502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.439901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pullan ST, Gidley MD, Jones RA, Barrett J, Stevanin TM, Read RC, Green J, Poole RK. Nitric oxide in chemostat-cultured Escherichia coli is sensed by Fnr and other global regulators: unaltered methionine biosynthesis indicates lack of S nitrosation. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:1845–1855. doi: 10.1128/JB.01354-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crack JC, Green J, Thomson AJ, Le Brun NE. Techniques for the production, isolation, and analysis of iron-sulfur proteins. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1122:33–48. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-794-5_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crack JC, Gaskell AA, Green J, Cheesman MR, Le Brun NE, Thomson AJ. Influence of the environment on the [4Fe–4S]2+ to [2Fe–2S]2+ cluster switch in the transcriptional regulator FNR. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1749–1758. doi: 10.1021/ja077455+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bates DM, Popescu CV, Khoroshilova N, Vogt K, Beinert H, Munck E, Kiley PJ. Substitution of leucine 28 with histidine in the Escherichia coli transcription factor FNR results in increased stability of the [4Fe–4S]2+ cluster to oxygen. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6234–6240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beinert H. Semi-micro methods for analysis of labile sulfide and of labile sulfide plus sulfane sulfur in unusually stable iron-sulfur proteins. Anal Biochem. 1983;131:373–378. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crack JC, Green J, Le Brun NE, Thomson AJ. Detection of sulfide release from the oxygen-sensing [4Fe–4S] cluster of FNR. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18909–18913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crack JC, Green J, Cheesman MR, Le Brun NE, Thomson AJ. Superoxide-mediated amplification of the oxygen-induced switch from [4Fe–4S] to [2Fe–2S] clusters in the transcriptional regulator FNR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2092–2097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609514104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Przysiecki CT, Meyer TE, Cusanovich MA. Circular dichroism and redox properties of high redox potential ferredoxins. Biochemistry. 1985;24:2542–2549. doi: 10.1021/bi00331a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crack JC, den Hengst CD, Jakimowicz P, Subramanian S, Johnson MK, Buttner MJ, Thomson AJ, Le Brun NE. Characterization of [4Fe–4S]-containing and cluster-free forms of Streptomyces WhiD. Biochemistry. 2009;48:12252–12264. doi: 10.1021/bi901498v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crack J, Green J, Thomson AJ. Mechanism of oxygen sensing by the bacterial transcription factor Fumarate-Nitrate Reduction (FNR) J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9278–9286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang B, Crack JC, Subramanian S, Green J, Thomson AJ, Le Brun NE, Johnson MK. Reversible cycling between cysteine persulfide-ligated [2Fe–2S] and cysteine-ligated [4Fe–4S] clusters in the FNR regulatory protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:15734–15739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208787109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Popescu CV, Bates DM, Beinert H, Munck E, Kiley PJ. Mössbauer spectroscopy as a tool for the study of activation/inactivation of the transcription regulator FNR in whole cells of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13431–13435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sutton VR, Stubna A, Patschkowski T, Munck E, Beinert H, Kiley PJ. Superoxide destroys the [2Fe–2S]2+ cluster of FNR from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2004;43:791–798. doi: 10.1021/bi0357053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan A, Kiley PJ. Techniques to isolate O2-sensitive proteins: [4Fe–4S]-FNR as an example. Meth Enzymol. 2009;463:787–805. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)63042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jervis AJ, Crack JC, White G, Artymiuk PJ, Cheesman MR, Thomson AJ, Le Brun NE, Green J. The O2 sensitivity of the transcription factor FNR is controlled by Ser24 modulating the kinetics of [4Fe–4S] to [2Fe–2S] conversion. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4659–4664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804943106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Melville SB, Gunsalus RP. Mutations in fnr that alter anaerobic regulation of electron transport-associated genes in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:18733–18736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kiley PJ, Reznikoff WS. Fnr mutants that activate gene expression in the presence of oxygen. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:16–22. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.1.16-22.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sawers G. The aerobic/anaerobic interface. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:181–187. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tseng CP, Albrecht J, Gunsalus RP. Effect of microaerophilic cell growth conditions on expression of the aerobic (cyoABCDE and cydAB) and anaerobic (narGHJI, frdABCD, and dmsABC) respiratory pathway genes in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1094–1098. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.4.1094-1098.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moore LJ, Kiley PJ. Characterization of the dimerization domain in the FNR transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45744–45750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106569200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Volbeda A, Darnault C, Renoux O, Nicolet Y, Fontecilla-Camps JC. The crystal structure of the global anaerobic transcriptional regulator FNR explains its extremely fine-tuned monomer-dimer equilibrium. Sci Adv. 2015;1:e1501086. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bouchal P, Struharova I, Budinska E, Sedo O, Vyhlidalova T, Zdrahal Z, van Spanning R, Kucera I. Unraveling an FNR based regulatory circuit in Paracoccus denitrificans using a proteomics-based approach. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:1350–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crack JC, Munnoch J, Dodd EL, Knowles F, Al Bassam MM, Kamali S, Holland AA, Cramer SP, Hamilton CJ, Johnson MK, Thomson AJ, Hutchings MI, Le Brun NE. NsrR from Streptomyces coelicolor is a nitric oxide-sensing [4Fe–4S] cluster protein with a specialized regulatory function. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:12689–12704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.643072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Filenko N, Spiro S, Browning DF, Squire D, Overton TW, Cole J, Constantinidou C. The NsrR regulon of Escherichia coli K-12 includes genes encoding the hybrid cluster protein and the periplasmic, respiratory nitrite reductase. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:4410–4417. doi: 10.1128/JB.00080-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee YY. Transcription factor NNR from Paracoccus denitrificans is a sensor of both nitric oxide and oxygen: isolation of nnr* alleles encoding effector-independent proteins and evidence for a haem-based sensing mechanism. Microbiology. 2006;152:1461–1470. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28796-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Spanning RJ, De Boer AP, Reijnders WN, Spiro S, Westerhoff HV, Stouthamer AH, van der Oost J. Nitrite and nitric oxide reduction in Paracoccus denitrificans is under the control of NNR, a regulatory protein that belongs to the FNR family of transcriptional activators. FEBS Lett. 1995;360:151–154. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00091-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Soding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Sys Biol. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nicholas KB, Nicholas HBJ (1997) Genedoc: a tool for editing and annotating multiple sequence alignments (Distributed by the authors)

- 55.Edwards J, Cole LJ, Green JB, Thomson MJ, Wood AJ, Whittingham JL, Moir JW. Binding to DNA protects Neisseria meningitidis fumarate and nitrate reductase regulator (FNR) from oxygen. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:1105–1112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.057810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.