Abstract

A few studies showed that long-term methotrexate (MTX) use exacerbates liver fibrosis and even leads to liver cirrhosis in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients. We therefore conducted a population-based cohort study to investigate the impact of long-term MTX use on the risk of chronic hepatitis B (CHB)-related cirrhosis among RA patients. We analyzed data from the National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan and identified 631 incident cases of RA among CHB patients (358 MTX users and 273 MTX non-users) from January 1, 1998 to December 31, 2007. After a median follow-up of more than 6 years since the diagnosis of CHB, a total of 41 (6.5%) patients developed liver cirrhosis. We did not find an increased risk of liver cirrhosis among CHB patients with long-term MTX use for RA. Furthermore, there was no occurrence of liver cirrhosis among 56 MTX users with a cumulative dose ≧3 grams after 97 months’ treatment. In conclusion, our data showed that long-term MTX use is not associated with an increased risk for liver cirrhosis among RA patients with CHB. However, interpretation of the results should be cautious due to potential bias in the cohort.

Methotrexate (MTX) is a commonly used immunosuppressant in the treatment of many autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis1. Early studies have shown that the prevalence of liver cirrhosis was as high as 26% among MTX-treated psoriasis patients2, but later studies demonstrated a lower risk (between 0% and 10%)3,4,5. MTX has been regarded as the anchor drug in the treatment of RA6,7. Among RA patients, a few studies showed that long-term MTX use may exacerbate liver fibrosis in sequential liver biopsies among RA patients8,9, whereas other studies did not find such an association10,11,12,13,14. Nonetheless, the risk of MTX-related liver cirrhosis in RA patients seems to be lower than that in psoriasis patients15. A meta-analysis demonstrated that 2.7% of RA patients would develop severe fibrosis or cirrhosis after 55 months’ MTX treatment16. Based on these findings, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) does not suggest routine performance of liver biopsy in RA patients who use MTX17.

Alcohol consumption, diabetes, obesity, chronic viral hepatitis and hepatotoxic medications have been reported to be etiological factors of liver cirrhosis18. In Taiwan, where hepatitis B is endemic19, the impact of long-term MTX use on the risk of chronic hepatitis B (CHB)-related cirrhosis among RA patients has not been investigated. We hypothesized that long-term MTX use increases the risk for liver cirrhosis among RA patients with CHB. We therefore conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from a nationwide health insurance database.

Methods

Patients

This retrospective cohort study analyzed data obtained from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD)20,21, established by the Taiwan National Health Research Institute. The NHIRD contains comprehensive health care data from more than 99% of the entire Taiwanese population of 24 million. Diseases in the NHIRD are coded with the International Classifications of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. In addition, we ensured that RA diagnosis was made according to the 1987 ACR criteria22 using the Catastrophic Illness Patient Database (CIPD), a registry including RA certified by two rheumatologists. Since the NHIRD contains only de-identified secondary data, the need for informed consent from individuals was waived.

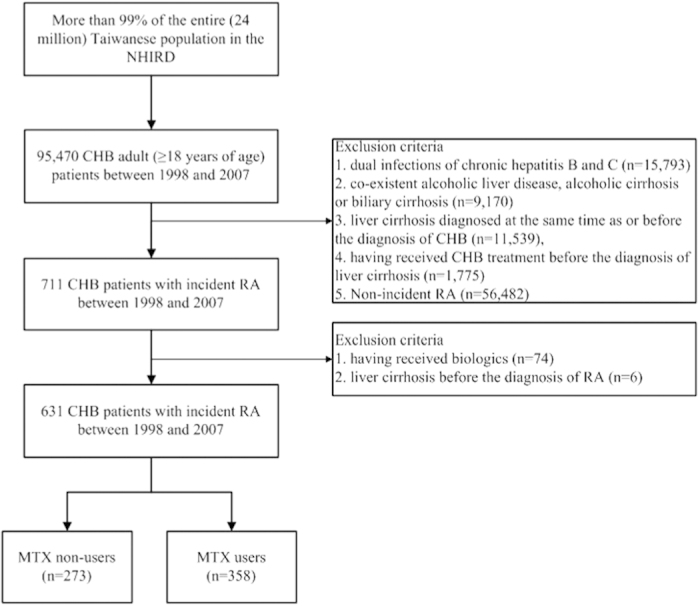

The study flowchart is illustrated in Fig. 1. We identified 95,470 adult patients who were diagnosed with CHB (ICD-9-CM codes 070.2, 070.3 or V02.61) in Taiwan from January 1, 1998 to December 31, 2007. Liver cirrhosis was defined as ICD-9-CM code 571.5. Exclusion criteria included dual infections of CHB and chronic hepatitis C (ICD-CM codes 070.54, 070.70 or V02.62), co-existent alcoholic liver disease (ICD-9-CM codes 571.0, 571.1 or 571.3), alcoholic cirrhosis (ICD-9-CM code 571.2) or biliary cirrhosis (ICD-9-CM code 571.6), pre-existing liver cirrhosis at the time of or before the diagnosis of CHB, and CHB treatment (lamivudine, adefovir dipivoxil, entecavir, telbivudine, tenofovir, or peginterferon alfa-2a) before the diagnosis of liver cirrhosis. We then identified 711 incident cases of RA among these CHB patients. Patients with liver cirrhosis before the diagnosis of RA or with prescription of biologics (etanercept, adalimumab, golimumab, abatacept, tocilizumab or rituximab) before the diagnosis of liver cirrhosis were excluded. In total, 631 CHB patients with incident RA (consisting of 358 MTX users and 273 MTX non-users) were identified and included in the final analysis. This study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taichung Veterans General Hospital (IRB TCVGH No. CE15124B).

Figure 1. The flow chart of identification of RA patients with CHB.

CHB, chronic hepatitis B; MTX, methotrexate; NHIRD, the National Health Insurance Research Database; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Clinical parameters

Risk factors for liver cirrhosis, such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD, ICD-9-CM code 571.8), diabetes mellitus (ICD-9-CM code 250) and dyslipidemia (ICD-9-CM code 272), as well as comorbidities such as hypertension (ICD-9-CM codes 401–405) were documented for each patient. Diagnosis of decompensated liver cirrhosis in all cases was confirmed by inclusion in the CIPD. One of the following criteria is needed for patients with liver cirrhosis to be registered in the CIPD: (1) intractable ascites, (2) variceal bleeding, or (3) hepatic coma or liver decompensation.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA.). All quantitative data are presented as means plus the standard deviation unless otherwise specified. For numerical variables, comparisons between subgroups of patients were performed using Student’s t test. For categorical variables, comparisons between subgroups of patients were performed using Chi-squared test. Hazard ratios of developing liver cirrhosis since the diagnosis of CHB between subgroups of RA patients with CHB were calculated using the Cox proportional hazards model after adjustment for age, gender and comorbidities such as NAFLD, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia and hypertension. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and the log rank test were used to compare the probability of liver cirrhosis-free survival since the diagnosis of CHB between MTX non-users and MTX users with different cumulative doses. A two-tailed p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of RA patients with CHB

Table 1 illustrates the baseline characteristics of RA patients with CHB. Leflunomide, sulfasalazine and corticosteroids were prescribed more often in MTX users than in MTX non-users, implying more severe disease activity of RA among MTX users. In our 358 MTX users, the average cumulative MTX dosage was 1.5 ± 1.6 grams after a mean of 40 months. We categorized them into 3 groups based on the cumulative MTX dose. The mean durations of treatment were 16, 55 and 97 months and the mean weekly doses were 8.5, 9.9 and 11.7 mg, within these groups of MTX users (MTX cumulative dose <1.5 grams, 1.5–3.0 grams and  grams). After a median follow-up of more than 6 years since the diagnosis of CHB, a total of 41 (6.5%) patients developed liver cirrhosis: 22 (6.1%) of 358 MTX users and 19 (7.0%) of 273 MTX non-users. Among the 22 MTX users who developed liver cirrhosis, 18 patients had a cumulative dose of ≦1.5 grams and 4 patients had a cumulative dose of ≧1.5 grams and <3.0 grams. Four (1.1%) of 358 MTX users and 2 (0.7%) of 273 MTX non-users developed decompensated liver cirrhosis. Notably, there was no occurrence of liver cirrhosis among 56 MTX users with a cumulative dose of ≧3 grams.

grams). After a median follow-up of more than 6 years since the diagnosis of CHB, a total of 41 (6.5%) patients developed liver cirrhosis: 22 (6.1%) of 358 MTX users and 19 (7.0%) of 273 MTX non-users. Among the 22 MTX users who developed liver cirrhosis, 18 patients had a cumulative dose of ≦1.5 grams and 4 patients had a cumulative dose of ≧1.5 grams and <3.0 grams. Four (1.1%) of 358 MTX users and 2 (0.7%) of 273 MTX non-users developed decompensated liver cirrhosis. Notably, there was no occurrence of liver cirrhosis among 56 MTX users with a cumulative dose of ≧3 grams.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of rheumatoid arthritis patients with chronic hepatitis B.

| Variables | MTX users (n = 358) | MTX non-users (n = 273) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 53.3 ± 12.7 | 54.8 ± 13.7# |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 274 (77%) | 206 (75%) |

| Male | 84 (23%) | 67 (25%) |

| Comorbidity | ||

| NAFLD | 2 (1%) | 3 (1%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 58 (16%) | 37 (14%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 55 (15%) | 46 (17%) |

| Hypertension | 95 (27%) | 79 (29%) |

| Concomitant medications | ||

| Leflunomide | 39 (11%) | 4 (2%)* |

| Azathioprine | 10 (3%) | 12 (4%) |

| Sulfasalazine | 190 (53%) | 91 (33%)* |

| Corticosteroids | 263 (74%) | 107 (39%)* |

| MTX | ||

| Cumulative dose <1.5 grams | 235 (66%) | NA |

| Cumulative dose 1.5–3.0 grams | 67 (19%) | NA |

| Cumulative dose ≧3.0 grams | 56 (16%) | NA |

| Liver cirrhosis | 22 (6%) | 19 (7%) |

| Decompensated liver cirrhosis | 4 (1%) | 2 (1%) |

| Median follow-up period (years) | 6.8 | 6.2## |

MTX: methotrexate; NA: not avalaible; NAFLD: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

*p < 0.0001.

#at diagnosis of chronic hepatitis B.

##since the diagnosis of chronic hepatitis B.

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for liver cirrhosis among RA patients with CHB

Table 2 illustrates risk factors for liver cirrhosis in RA patients with CHB utilizing the Cox proportional hazards model. Older age at diagnosis of CHB and male sex were risk factors for liver cirrhosis. There was a trend toward an increased hazard for liver cirrhosis in patients with NAFLD, with an hazard ratio of 9.21 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.18–71.66). The concomitant use of MTX was not associated with an increased hazard of liver cirrhosis (hazard ratio: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.48–1.68), even for MTX users with a cumulative dose of ≧1.5 grams (hazard ratio: 0.39, 95% CI: 0.13–1.17, Appendix 1), when compared to MTX non-users.

Table 2. Multivariate analysis for liver cirrhosis in rheumatoid arthritis patients with chronic hepatitis B.

| Variables | Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis of chronic hepatitis B (years) | 1.07 (1.04–1.11) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 1.00 |

| Male | 3.90 (2.08–7.29)** |

| Concomitant MTX use | 0.90 (0.48–1.68) |

| Comorbidity | |

| NAFLD | 9.21 (1.18–71.66)* |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.32 (0.56–3.08) |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.42 (0.15–1.17) |

| Hypertension | 1.28 (0.63–2.58) |

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.001.

CI: confidence interval; MTX: methotrexate; NAFLD:

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Subgroup analysis of the incidence rates of liver cirrhosis among RA patients with CHB

Table 3 illustrates the subgroup analysis of the incidence rates of liver cirrhosis among RA patients with CHB. Among patients with diabetes mellitus, there was a lower incidence rate of liver cirrhosis among MTX users compared to MTX non-users (8.1 versus 26.0 events per 1000 person-years, p = 0.041). Among patients with concomitant use of sulfasalazine, we observed a trend toward a higher incidence rate of liver cirrhosis among MTX users when compared to MTX non-users (11.5 versus 4.8 events per 1000 person-years, p = 0.083).

Table 3. Subgroup analysis for new-onset liver cirrhosis in rheumatoid arthritis patients with chronic hepatitis B.

| Variables | MTX users | MTX non-users | Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence rate of liver cirrhosis (per 1,000 person-years) | Incidence rate of liver cirrhosis (per 1,000 person-years) | ||

| All patients | 9.1 | 10.5 | 0.92 (0.48–1.77) |

| Age at the diagnosis of chronic hepatitis B (years) | |||

| 18–44 | 1.5 | 0.0 | NA |

| 45–64 | 5.8 | 13.7 | 0.48 (0.19–1.25) |

| ≧65 | 35.0 | 20.6 | 1.41 (0.50–4.01) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 5.7 | 6.4 | 1.16 (0.46–2.93) |

| Male | 23.0 | 25.2 | 0.74 (0.29–1.86) |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 8.1 | 26.0 | 0.16 (0.03–0.92) |

| Dyslipidemia | 2.5 | 14.8 | 0.17 (0.02–1.76) |

| Hypertension | 12.9 | 18.0 | 0.77 (0.28–2.10) |

| Concomitant medications | |||

| Sulfasalazine | 11.5 | 4.8 | 3.25 (0.86–12.27) |

| Corticosteroids | 3.9 | 24.9 | 1.41 (0.58–3.43) |

CI: confidence interval; MTX: methotrexate; NA: not available.

*adjusted for age, gender, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hypertension and medications such as sulfasalazine and corticosteroids.

The probability of liver cirrhosis-free survival among RA patients with CHB

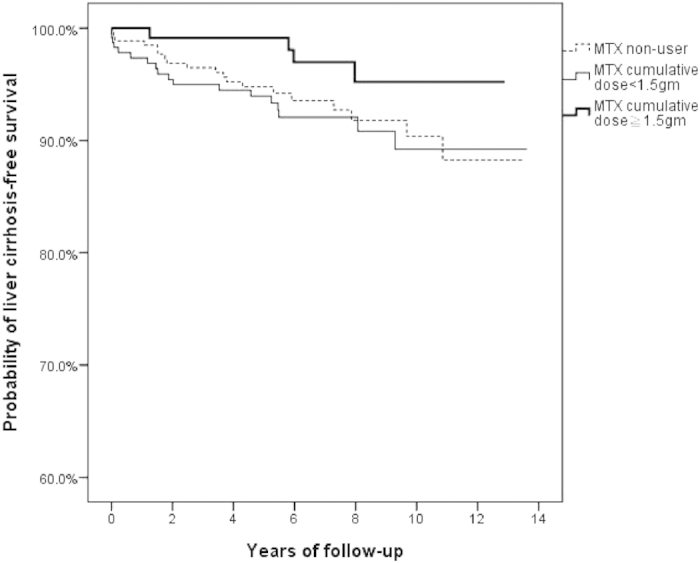

Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of liver cirrhosis-free survival with respect to MTX use among RA patients with CHB. There was no statistically significant difference between MTX non-users and MTX users with different cumulative doses (p = 0.176, log-rank test), although there was a trend toward a higher probability of liver cirrhosis-free survival among MTX users with a cumulative dose of ≧1.5 grams when compared to MTX non-users and MTX users with a cumulative dose of <1.5 grams.

Figure 2. Probability of liver cirrhosis-free survival among MTX users with different cumulative doses and MTX non-users (p = 0.176, log-rank test).

MTX, methotrexate.

Discussion

This population-based cohort study investigated the impact of long-term MTX use on the risk of liver cirrhosis among RA patients with CHB. Our results demonstrate no significant increase of liver cirrhosis in RA patients with CHB who received long-term MTX treatment. However, no firm conclusion can be drawn due to potential bias in the cohort.

Among RA patients with CHB in Taiwan, 358 (57%) of 631 patients (excluding those patients who had received biologics) had received MTX to treat RA. The proportion of MTX used in our study was lower than that reported in a multi-national cross-sectional study of RA patients23, perhaps due to the reluctance of physicians to use MTX in these patients. However, MTX was still used by over half of RA patients with CHB, reflecting its fundamental role in RA treatment even in an endemic area for CHB. As for comorbidities, the prevalence of NAFLD in our RA patients was lower than rates reported in earlier studies that described liver biopsy findings in RA patients24,25, probably due to suboptimal monitoring of RA patients for comorbidities23.

After a median follow-up of more than 6 years since the diagnosis of CHB, 41 (6.5%) of 703 RA patients with CHB developed liver cirrhosis. The incidence of liver cirrhosis in our study was higher than that in the general population with CHB (3.0% after a mean follow-up of more than 9 years)26. However, it should be noted that RA patients with CHB were predominantly female and older in age. The discrepancy in demographic characteristics and the lack of adjustment for confounding variables should be taken into consideration when viewing our higher incidence of liver cirrhosis in CHB patients with comorbid RA. Further epidemiological study is needed.

Previous studies indicated that the risk for liver cirrhosis after long-term MTX therapy is low among RA patients16. But it was unclear whether there was an increased risk among patients with comorbidities that contribute to liver cirrhosis, such as CHB. In our study, a comparable proportion of MTX users and MTX non-users developed liver cirrhosis (6.2% vs. 7.0%) and decompensated liver cirrhosis (1.1% vs. 0.7%). In the Cox proportional hazards model, older age and male sex were identified as risk factors of developing liver cirrhosis among RA patients with CHB, which is compatible with previous findings27. However, we did not find an increased hazard for liver cirrhosis or a significant difference in liver cirrhosis-free survival among MTX users when compared to MTX non-users, although higher proportions of concomitant use of hepatotoxic drugs such as sulfasalazine and leflunomide1, and corticosteroids, which are associated with hepatitis B reactivation28, were found in MTX users. Even for those patients who used a higher cumulative dose of MTX (≧1.5 grams), there was no such increased risk of liver cirrhosis. Furthermore, there was no occurrence of liver cirrhosis among 56 MTX users with a cumulative dose of ≧3 grams after 97 months’ treatment. Taken together, these findings implied that long-term MTX use was not associated with an increased risk of liver cirrhosis among RA patients with CHB. Our results are consistent with previous observational studies demonstrating the low risk of MTX-related liver cirrhosis in RA patients16.

However, it is difficult to draw a firm conclusion from our data since such cohort is easily biased despite efforts to adjust for confounding variables. Nevertheless, analysis using a real-world database can still provide insight regarding the issue. We gave a possible explanation for our observations16. Compared to MTX users, MTX non-users seemed to have less severe disease activity, which is associated with higher body mass index29,30. This was correlated with the development of NAFLD31, which contributed to the development of liver cirrhosis31. The potential impact of NAFLD in our study is reflected in the increased hazard of liver cirrhosis among MTX non-users when compared to MTX users in the subgroup of patients with diabetes mellitus, which is associated with NAFLD31. Although we did not find a difference in the prevalence of diagnosed NAFLD between MTX users and non-users, the true prevalence of NAFLD might be underestimated due to the reason described above. Interestingly, a recent analysis of individuals who had been listed for, and/or received liver transplantation in the US., found that the burden of end-stage MTX-related liver disease is exceedingly small and the risk factor profile of MTX-related liver disease is similar to that of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), suggesting a common pathogenesis32.

Our study has a number of advantages. First, it is difficult to conduct a randomized control trial to evaluate the impact of long-term MTX use on the risk of CHB-related liver cirrhosis. Therefore our data, based on a population-based cohort from a database containing the healthcare records of 24 million people, can still provide important insight. Second, unlike previous studies that mainly focused on liver fibrosis8,9,10,11,12,13,14, our study investigated clinically manifest liver cirrhosis, which leads to morbidities and mortality18.

Our study has some limitations. First, a longer follow-up period with a higher cumulative MTX dose may be required to observe the contribution of MTX to the risk of HBV-related liver cirrhosis. Therefore, a study with a longer follow-up is needed to confirm our results. Second, previous studies demonstrated that the adherence rate to MTX ranged from 59% (underuse) to 107% (overuse)33. However, it is difficult to evaluate the adherence to medications in an observational study, particularly in a claims database. Therefore the medication effect might be underestimated due to nonadherence. Third, anthropometric measurements are not available in the NHIRD and therefore we could not evaluate the impact of body mass index, which is associated with the development of NAFLD31. Fourth, daily alcohol consumption is not documented in the NHIRD. However, the prevalence of alcohol-related health problems seems to be lower in Taiwan compared with Western countries34. In addition, patients with co-existent alcoholic liver disease and/or alcoholic cirrhosis were excluded from the study cohort. Therefore, the lack of documented daily alcohol consumption was not expected to markedly bias our study results. Fifth, it is possible that some patients with active CHB presented with elevated liver enzymes27, thereby preventing MTX use and contributing to a higher risk for liver cirrhosis among MTX non-users27. However, patients with active CHB (receiving CHB treatment) were excluded from this cohort and such selection bias was reduced.

In conclusion, our data showed that long-term MTX use is not associated with an increased risk for liver cirrhosis among RA patients with CHB. However, interpretation of the results should be cautious due to potential bias in the cohort.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Tang, K.-T. et al. Methotrexate is not associated with increased liver cirrhosis in a population-based cohort of rheumatoid arthritis patients with chronic hepatitis B. Sci. Rep. 6, 22387; doi: 10.1038/srep22387 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study is based in part on data from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare and managed by National Health Research Institutes (Registered number 101095, 102148). The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare or National Health Research Institutes. This study was supported in part by grants from Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taiwan (TCVGH-NHRI10405, TCVGH-1047324D, TCVGH-1047312C, TCVGH-104G211) and the National Science Council, Taiwan (MOST 103-2314-B-075A-006). The authors would like to thank the Healthcare Service Research Center (HSRC) of Taichung Veterans General Hospital for statistical support.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Conceived and designed the experiments: K.T.T., C.H.L. and D.Y.C. Performed the experiments: K.T.T.and C.H.L. Analyzed the data: K.T.T., Y.H.C. and C.H.L. Prepare Tables and Figures: K.T.T., W.T.H. and C.H.L. Wrote the paper: K.T.T. and D.Y.C. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Aithal G. P. Hepatotoxicity related to antirheumatic drugs. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 7, 139–150 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariae H., Kragballe K. & Sogaard H. Methotrexate induced liver cirrhosis. Studies including serial liver biopsies during continued treatment. Br. J. Dermatol. 102, 407–412 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aithal G. P. et al. Monitoring methotrexate-induced hepatic fibrosis in patients with psoriasis: are serial liver biopsies justified? Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 19, 391–399 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Themido R., Loureiro M., Pecegueiro M., Brandao M. & Campos M. C. Methotrexate hepatotoxicity in psoriatic patients submitted to long-term therapy. Acta Derm. Venereol. 72, 361–364 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boffa M. J., Chalmers R. J., Haboubi N. Y., Shomaf M. & Mitchell D. M. Sequential liver biopsies during long-term methotrexate treatment for psoriasis: a reappraisal. Br. J. Dermatol. 133, 774–778 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J. A. et al. 2012 update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken) 64, 625–639 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolen J. S. et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis . 73, 492–509 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer J. M., Lee R. G. & Tolman K. G. Liver histology in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving long-term methotrexate therapy. A prospective study with baseline and sequential biopsy samples. Arthritis Rheum. 32, 121–127 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer J. M., Kaye G. I., Kaye N. W., Ishak K. G. & Axiotis C. A. Light and electron microscopic analysis of sequential liver biopsy samples from rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving long-term methotrexate therapy. Followup over long treatment intervals and correlation with clinical and laboratory variables. Arthritis Rheum. 38, 1194–1203 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aponte J. & Petrelli M. Histopathologic findings in the liver of rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with long-term bolus methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum. 31, 1457–1464 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rau R., Karger T., Herborn G. & Frenzel H. Liver biopsy findings in patients with rheumatoid arthritis undergoing longterm treatment with methotrexate. J. Rheumatol. 16, 489–493 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard S., Guerret S., Gerard F., Tebib J. G. & Vignon E. Hepatic fibrosis in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with methotrexate: application of a new semi-quantitative scoring system. Rheumatology (Oxford) 39, 50–54 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkman D. J., Boschert M., Tolman K. G., Clegg D. O. & Ward J. R. The effect of long-term methotrexate therapy on hepatic fibrosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 36, 1697–1701 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ros S. et al. Light and electron microscopic analysis of liver biopsy samples from rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving long-term methotrexate therapy. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 31, 330–336 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariae H. Liver biopsies and methotrexate: a time for reconsideration? J Am. Acad. Dermatol. 42, 531–534 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiting-O’Keefe Q. E., Fye K. H. & Sack K. D. Methotrexate and histologic hepatic abnormalities: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Med. 90, 711–716 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer J. M. et al. Methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. Suggested guidelines for monitoring liver toxicity. American College of Rheumatology. Arthritis Rheum. 37, 316–328 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidelbaugh J. J. & Sherbondy M. Cirrhosis and chronic liver failure: part II. Complications and treatment. Am. Fam. Physician 74, 767–776 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merican I. et al. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Asian countries. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15, 1356–1361 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. W. et al. Osteoarthritis increases the risk of dementia: a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. Sci. Rep. 5, 10145 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung C. Y. et al. Age and CHADS2 Score Predict the Effectiveness of Renin-Angiotensin System Blockers on Primary Prevention of Atrial Fibrillation. Sci. Rep. 5, 11442 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett F. C. et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 31, 315–324 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougados M. et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in rheumatoid arthritis and evaluation of their monitoring: results of an international, cross-sectional study (COMORA). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73, 62–68 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrichson O., From A., Christoffersen P. & Juhl E. Morphological changes in liver biopsies from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 5, 65–69 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rau R., Pfenninger K. & Boni A. Proceedings: Liver function tests and liver biopsies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 34, 198–199 (1975). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. W. et al. Increased risk of cirrhosis and its decompensation in chronic hepatitis B patients with newly diagnosed diabetes: a nationwide cohort study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 57, 1695–1702 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. J. & Yang H. I. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B REVEALed. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 26, 628–638 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng A. L. et al. Steroid-free chemotherapy decreases risk of hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in HBV-carriers with lymphoma. Hepatology 37, 1320–1328 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming A., Crown J. M. & Corbett M. Prognostic value of early features in rheumatoid disease. Br. Med. J. 1, 1243–1245 (1976). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann J., Kielstein V., Kilian S., Stein G. & Hein G. Relation between body mass index and radiological progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 30, 2350–2355 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalasani N. et al. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Hepatology 55, 2005–2023 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawwas M. F. & Aithal G. P. End-stage methotrexate-related liver disease is rare and associated with features of the metabolic syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 40, 938–948 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bemt B. J., Zwikker H. E. & van den Ende C. H. Medication adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a critical appraisal of the existing literature. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 8, 337–351 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W. J., Cheng Y., Huang M. C. & Chen C. J. Alcohol dependence, consumption of alcoholic energy drinks and associated work characteristics in the Taiwan working population. Alcohol Alcohol. 47, 372–379 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.