Abstract

In the past decade, the armamentarium of targeted therapy agents for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) has significantly increased. Improvements in response rates and survival, with more manageable side effects compared with interleukin 2/interferon immunotherapy, have been reported with the use of targeted therapy agents, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (sunitinib, sorafenib, pazopanib, axitinib), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors (everolimus and temsirolimus) and VEGF receptor antibodies (bevacizumab). Current guidelines reflect these new therapeutic approaches with treatments based on risk category, histology and line of therapy in the metastatic setting. However, while radical nephrectomy remains the standard of care for locally advanced RCC, the migration and use of these agents from salvage to the neoadjuvant setting for large unresectable masses, high-level venous tumor thrombus involvement, and patients with imperative indications for nephron sparing has been increasingly described in the literature. Several trials have recently been published and some are still recruiting patients in the neoadjuvant setting. While the results of these trials will inform and guide the use of these agents in the neoadjuvant setting, there still remains a considerable lack of consensus in the literature regarding the effectiveness, safety and clinical utility of neoadjuvant therapy. The goal of this review is to shed light on the current body of evidence with regards to the use of neoadjuvant treatments in the setting of locally advanced RCC.

Keywords: locally advanced, neoadjuvant, nephrectomy, preoperative, presurgical, renal cell carcinoma, targeted therapy

Introduction

In general, ‘preoperative’ or ‘presurgical’ therapy is defined as a cancer therapy that precedes the main treatment modality, in this case, surgery. In an organ-confined or locally advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) setting in the absence of metastasis (M0), preoperative therapy is intended predominantly to target the primary mass to prevent further local progression and possibly metastatic disease. In this setting, surgery is aimed to render the patient to a disease-free status. However, preoperative therapies in patients with known metastatic disease (M1) target not only larger tumor burden, but also multiple tumor foci. Preoperative therapy in this setting can potentially act as a litmus test for the assessment of therapy response.

The term ‘neoadjuvant’ should be carefully utilized, and for the purpose of reporting, we recommend using the term ‘neoadjuvant’ therapy solely in M0 patients and the term ‘pseudoneoadjuvant’ therapy in M1 patients. In this case, both ‘neoadjuvant’ and ‘pseudoneoadjuvant’ terms fall under the ‘preoperative’ or ‘presurgical’ umbrellas.

While the use of preoperative therapy in the setting of locally advanced or metastatic RCC (mRCC) is still in its preliminary stages and requires more detailed study, there is a growing body of evidence that may support its role in a select group of patients. In this review, we examine the evidence for preoperative therapy in RCC with regards to its safety and explore its role in tumor downsizing, improving surgical resectability, and downstaging both the primary tumor and venous tumor thrombus.

Interest in preoperative therapy

In general, there is consensus within the urologic oncology community on the importance and interest in participation in preoperative clinical trials in RCC, especially in the locally advanced setting [Tobert et al. 2013]. One argument among proponents for the use of preoperative therapy is the possibility of eradicating micrometastatic disease [Jonasch et al. 2009; Timsit et al. 2012]. Furthermore, primary tumor downsizing or downstaging may decrease surgical morbidity, allowing nephron-sparing or minimally invasive approaches, and improve patient recovery [Posadas and Figlin, 2014]. Along the same lines, evidence of oncological response to therapy may potentially influence therapy selection if metastatic recurrence were to occur [Jonasch et al. 2009]. Preoperative therapies may also contribute to better understanding of the disease sensitivity to certain agents and aid in future treatment selection.

However, opponents of this approach have resisted the idea of neoadjuvant therapy for RCC based on the fact that the treatment breach or gap in definitive treatment would increase the probability for the tumor to progress locally, regionally or systemically, thereby losing the ‘window of opportunity’ for cure [Shuch et al. 2008]. It has also been noted that therapy may alter tumor biology of metastatic disease adversely [Griffioen et al. 2012]. Moreover, although recent studies have shown no increase in overall complication rates and minor wound delay complications [Chapin et al. 2011], toxicity of therapy and its increase in surgical morbidity has been suggested as a possible downside.

Most importantly, it has been suggested that improvement in patient outcomes will determine the future use and recommendations of targeted therapy in the setting of neoadjuvant therapy [Wood and Margulis, 2009].

First report

The first documented use of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) as a preoperative treatment in the setting of mRCC was by Van der Veldt and colleagues, with 17 evaluable patients receiving sunitinib for a course of 4 weeks [Van der Veldt et al. 2008]. In their retrospective study, drug-induced primary tumor response was the primary endpoint, assessed by computed tomography (CT) scans according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST). Upfront nephrectomy was not done in this cohort due to a surgically unresectable tumor mass (n = 10) or extensive metastatic burden, which was defined as the sum of the diameter of the metastases exceeding the diameter of the primary tumor (n = 6). Additionally, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) poor risk, solitary kidney and advanced age contributed to this decision. Overall, there were four patients with partial responses (PRs), 12 with stable disease (SD) and one with progressive disease (PD). The overall response rate in the primary tumor was 23%, with the most significant decrease in tumor volume in patients with PR and SD with a median reduction of 31% (p = 0.001). Tumor downsizing for surgical excision of the primary tumor was achieved in three ‘unresectable’ patients [Van Der Veldt et al. 2008]. Although this study was a small retrospective case series with limited follow up, it laid the groundwork for further research into the role of neoadjuvant therapy in locally advanced RCC.

Safety

One of the major criticisms of preoperative therapy with targeted therapy for locally advanced RCC and mRCC is the concern regarding wound complications in the perioperative period. Agents such as bevacizumab have been shown to result in significant wound complications that potentially increase the morbidity of the treatment [Jonasch et al. 2009], as 20.9% of the patients had either wound dehiscence or delayed wound healing. These findings were significantly higher than those published in other studies and historical comparison groups (20.9% versus 2%; p < 0.001). However, Cowey and colleagues did not observe any delayed wound healing, dehiscence or excessive bleeding in their prospective study of sorafenib in 30 patients [Cowey et al. 2010a]. There were no grade 4–5 toxicity or adverse surgical complications despite discontinuing treatment up to a median of 3 days prior to surgery. As suggested by the authors, the shorter half life of sorafenib compared with bevacizumab may explain these findings. Powles and colleagues reported a 13% rate of delayed wound complications in their study of preoperative sunitinib in two phase II trials in the metastatic setting. [Powles et al. 2011b]. In the neoadjuvant axitinib study (in which axitinib was stopped 36 h prior to surgery) [Karam et al. 2014], only one patient (4.2%) experienced a superficial wound healing complication, which resolved with conservative management. In the neoadjuvant pazopanib study [Rini et al. 2015], none of the patients experienced a fascial dehiscence or wound healing impairment.

In a further study, Chapin and colleagues retrospectively analyzed patients with synchronous mRCC from the MD Anderson Cancer Center, comparing surgical outcomes in 70 patients receiving preoperative systemic targeted therapy prior to cytoreductive nephrectomy and 103 patients undergoing immediate cytoreductive nephrectomy [Chapin et al. 2011]. All of the postoperative complications were assessed using the modified Clavien system within the first 12 months. The study showed no increase in the overall complications rate among the groups [odds ratio (OR) 1.5, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.77–2.9, p = 0.237]. Furthermore, the risk of severe complications requiring an intervention (Clavien ⩾ 3) was no greater after preoperative targeted therapy than with upfront cytoreductive nephrectomy (p = 0.625). However, when stratified by type of wound complication, patients who underwent preoperative treatment were more likely to develop delayed (>90 days) wound complications, superficial wound dehiscence and wound infection compared with the nontreated group. While preoperative targeted therapy and body mass index greater than 30 were statistically significant on univariate analysis, preoperative targeted therapy was the most important predictor for wound complication on multivariate analysis (OR 4.14, 95% CI 1.6–10.6, p = 0.003). These results are also in agreement with previous studies in breast and colorectal cancer, illustrating the likelihood of delayed wound healing in patients who undergo neoadjuvant therapy with similar agents [Golshan et al. 2011; Hurwitz et al. 2004]. Lastly, although the majority of patients enrolled were treated with agents with a long half life such as bevacizumab, this was not found to be an independent predictor of overall complications [Chapin et al. 2011].

Tumor downsizing

Even though targeted therapy has been beneficial for patients in the metastatic setting, the role of targeted therapy in the preoperative treatment of primary renal masses with the endpoint of tumor burden reduction and improved surgical resectability had been rather uncertain. Table 1 summarizes studies reporting tumor size changes following preoperative therapy.

Table 1.

Results of contemporary clinical trials for preoperative therapy for RCC.

| References | No. patients | Agent | No. patients with M0 (%) | Clear cell histology (%) | Median renal tumor diameter reduction (%) | Absolute change in renal tumor diameter (cm) | Renal tumor RECIST response PR + CR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jonasch et al. [2009] | 50 | Bevacizumab | 0 | 96 | N/A | NR | 0 |

| Cowey et al. [2010a] | 30 | Sorafenib | 56 | 70 | 9.6 | 0.8 (median) | 7 |

| Silberstein et al. [2010] | 12 | Sunitinib | 58 | 100 | 21.1 (mean) | 1.5 (mean) | 28 |

| Hellenthal et al. [2010] | 20 | Sunitinib | 80 | 100 | 11.8 (mean) | NR | 5 |

| Powles et al. [2011a] | 66 | Sunitinib | 0 | 100 | 13 | NR | 6 |

| Rini et al. [2012] | 28 | Sunitinib | 34 | 75 | 22 | 1.7 (median) | 37 |

| Powles et al. [2013] | 102 | Pazopanib | 0 | 100 | 14 | NR | 14 |

| Karam et al. [2014] | 24 | Axitinib | 100 | 100 | 28.3 | 3.1 (median) | 46 |

| Lane et al. [2015] | 72 | Sunitinib | 60 | 85 | 18 | 1.3 (median) | 19 |

| Rini et al. [2015] | 25 | Pazopanib | 100 | 100 | 26 | 1.5 (median) | 36 |

| Zhang et al. [2015] | 18 | Sorafenib | 61.1 | 83.3 | 20.5 (mean) | 1.6 (mean) | 22.2 |

CR, complete response; N/A, not applicable; NR, not reported; PR, partial response; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors.

Jonasch and colleagues studied the safety and response rates of bevacizumab in the preoperative setting in mRCC [Jonasch et al. 2009]. A total of 50 patients were analyzed and 41 (82%) and nine (18%) were categorized as intermediate and poor risk based on the MSKCC criteria, respectively. The study showed a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 11 months (95% CI 5.5–15.6 months) with an overall response rate of 12% (95% CI 5–24%) and a median overall survival of 25.4 months (95% CI 11.4 months to not reached). Furthermore, the primary tumor response rates based on RECIST showed no formal PR; however, 23 patients (52%) showed a decrease in tumor size. The survival outcomes appeared to be within the expected range compared with those treated in a standard fashion, indicating lack of harm by giving patients preoperative therapy prior to nephrectomy.

Cowey and colleagues reported on a preoperative phase II clinical trial with sorafenib in patients with stage II or higher renal masses [Cowey et al. 2010a]. Among the 30 patients enrolled, 17 (44%) had metastatic disease. Radiographic response was assessed based on RECIST, however in addition to this, densitometric measurements of tumor enhancement and three-dimensional mass reconstruction were performed in order to estimate tumor viability with modified Choi criteria. The median primary tumor reduction in response to sorafenib was 9.6% and while the majority of patients had SD based on RECIST (96%) with only two who met PR, there were no patients confirmed with PD and the absolute and logarithmic differences between the pretreatment and post-treatment tumor diameters were found to be significantly small (p < .0001). Furthermore, intratumoral enhancement was significantly decreased with a median of 13%. These additional findings may well represent radiographic evidence of tumor necrosis, thus visually exemplifying the antiangiogenic effect of targeted therapy on primary tumor cells.

Silberstein and colleagues reported on a cohort of 12 patients (with chronic kidney disease, solitary kidney or bilateral tumors) with RCC (14 tumor units) who received two cycles of sunitinib [Silberstein et al. 2010]. Five patients had mRCC and all patients had clear cell RCC. Mean reduction in tumor diameter was 21.1% (range 3.2–45). Moreover, absolute primary tumor diameter decreased by 1.5 cm (range 0.2–3.2 cm). According to RECIST, no tumor showed PD, four experienced PR and 10 had SD.

Hellenthal and colleagues prospectively studied 20 patients with biopsy-proven clear cell RCC treated with preoperative sunitinib for 3 months [Hellenthal et al. 2010]. A total of 17 (85%) patients experienced a reduction of tumor diameter, with a mean change of 11.8%. Contrast enhancement on CT scans decreased in 15 (75%) with a mean hounsfield units (HU) change of 22%. Based on RECIST, one patient had a PR while all others experienced SD. Following treatment, eight patients with clinical T1b disease underwent laparoscopic partial nephrectomy.

Powles and colleagues investigated the outcomes of 66 patients with mRCC who received preoperative sunitinib for 2-3 cycles (4 weeks on, 2 weeks off) [Powles et al. 2011a]. Overall, the median reduction in the longest diameter of primary tumor was 13%. Based on RECIST, no patient experienced PD or was deemed inoperable due to treatment. Nonetheless, while an overall clinical benefit, established as rate of PR + SD, was observed in 48 (73%) patients, no substantial responses were observed in the primary renal tumor, with only four (6%) patients experiencing a PR of the primary tumor. Interestingly, the authors noted that 36% of patients experienced PD while on the 4-week planned treatment break prior to cytoreductive nephrectomy. The appropriate length of a surgically necessary treatment break has been controversial given the observed wound-associated complications in different studies, and even though reintroduction of sunitinib therapy had resulted in SD in (76%) of the patients, the authors concluded that further research is needed to assess these particular concerns.

Rini and colleagues observed a more dramatic tumor response with preoperative treatment of sunitinib [Rini et al. 2012]. Among 28 patients who were evaluable for response, a median of 22% in tumor diameter reduction was observed, with 37% of tumors presenting PR or more based on RECIST. The authors attributed the higher percentage of response rate to the increased (50 mg) doses of continuous sunitinib compared with other series. Despite the fact that the percentage of primary tumor reduction was statistically significant, the absolute magnitude of diameter decrease was limited for most cases.

Powles and colleagues reported the outcomes of a single arm phase II study of a 102 patients with mRCC treated with pazopanib for 12–14 weeks [Powles et al. 2013]. A total of 81% had SD, with 14% achieving PR. The median size reduction of the primary tumor was 14%. Again, a high percentage of patients (26%) experienced progression during the treatment-free interval.

Rini and colleagues reported on 25 patients receiving daily pazopanib as part of a phase II trial [Rini et al. 2015]. A total of 92% of tumor units experienced size reduction, with a median absolute decrease of 1.5 cm and median change relative to baseline of 26%. PR rate was 32% with a decrease in RENAL complexity score of 36%.

In a retrospective series by Lane and colleagues, 72 potential candidates for surgery treated with sunitinib with primary tumor in situ were analyzed [Lane et al. 2015]. Sixty percent of the patients had nonmetastatic locally advanced RCC. Ultimately, 62 patients (86%) underwent surgery. The results showed a significant primary median tumor size reduction from the initial 7.2 cm [interquartile range (IQR) 5.3–8.7 cm] to the post treatment size of 5.3 cm (IQR 4.1–7.5 cm) (p < 0.0001). Overall, treatment resulted in a 32% reduction of tumor area (IQR 14–46%), with 15 (19%) patients experiencing PR. This study also found that absence of lymph node involvement, clear cell histology and low Fuhrman grade were significant predictors of increased response according to RECIST and World Health Organization (WHO) criteria.

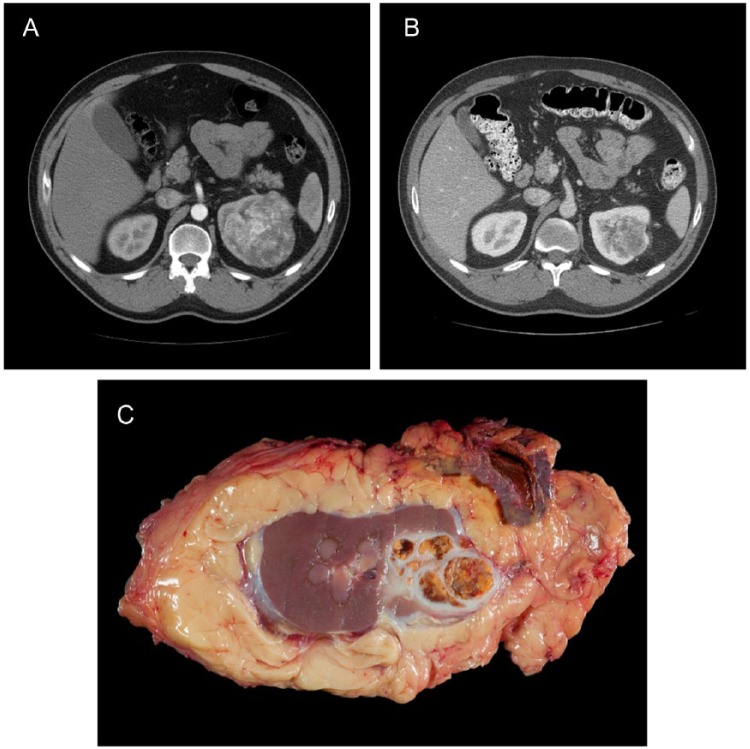

Lastly, a recent phase II clinical trial published by Karam and colleagues reported on the experience with neoadjuvant axitinib in 24 patients with biopsy-proven clear cell locally advanced nonmetastatic RCC [Karam et al. 2014]. Patients received daily axitinib for 12 weeks, which was discontinued only 36 h prior to nephrectomy. All of the evaluable patients showed tumor shrinkage, with a median primary tumor diameter reduction of 28.3% (range 5.3–42.9) and an absolute median tumor diameter change from 10.0 cm (range 4.2–16.6) to 6.9 cm (range 2.4–11.6). A total of 45.8% showed PR with the rest having SD, and no patient having PD. While some unusual fibrosis or tissue adherence surrounding the kidney was encountered during surgery, no intraoperative complications were reported. Representative CT scans and radical nephrectomy gross specimen are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography scan before (A) and after (B) treatment with 12 weeks of axitinib, plus radical nephrectomy gross specimen. Radical nephrectomy specimen after treatment with axitinib (C).

Changing the unresectable to resectable

One of the potential advantages of preoperative systemic therapy is the possibility of converting an otherwise unresectable mass to a surgically feasible resection. Although multiple studies have been reported in the literature, there is tremendous heterogeneity as many of these studies have a wide range of tumor stages and unstandardized evaluation and treatment protocols. The definition of surgical resectability plays a key role and is unfortunately quite variable, as it relies on multiple factors including the skill and experience of the surgeon, availability of multidisciplinary surgical teams, and the extent of ancillary services available at the treatment facility, in addition to tumor and anatomy-specific factors. Despite the heterogeneous data, initial results suggest that this approach may be of some advantage in patients with truly unresectable tumors.

In a retrospective study by Thomas and colleagues, a total of 19 patients with advanced RCC deemed unfit for surgery due to unresectable or bilateral tumors not amenable to partial nephrectomy were treated with a median of two cycles of sunitinib until the primary tumor was considered resectable by the operating surgeon, or until evidence of disease progression was found or adverse events occurred [Thomas et al. 2009]. Tumors were initially called unresectable due to bulky lymphadenopathy (one patient), adjacent organ or vascular invasion (three patients), high risk due to proximity to vital vessels (three patients) or due to high metastatic burden. Fifteen patients in this cohort had metastatic disease. Overall, four (21%) patients had disease that responded adequately enough to be deemed resectable and underwent radical nephrectomy. Final pathology was clear cell RCC with remaining viable tumor in all specimens. Sunitinib was found to decrease primary median tumor size by 16% (range 11–24%) and to significantly decrease tumor burden in the patients with metastatic disease. In addition, no major complications were reported and all surgical patients were alive at last follow up (median 6 months, range 1–15 months).

In another retrospective series published by Bex and colleagues, 10 patients with clear cell mRCC and complex primary tumors or bulky loco-regional metastasis underwent preoperative palliative treatment with sunitinib for 4 weeks on and 2 weeks off [Bex et al. 2009]. Unresectable tumors were defined as a primary or retroperitoneal tumor with direct adjacent organ invasion or encasement of vital organs on imaging. Limited tumor response was observed, with a median reduction of tumor size of 14% and none of the 10 primary tumors experiencing a PR. Ultimately, only three patients had disease deemed resectable after treatment and underwent radical nephrectomy. Downsizing was most notably seen in the distant metastases, with a reduction of 56%, 45% and 100% in size, along with an improvement of performance status from Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Perfomance Status (ECOG) 2 to 1 or 0. Furthermore, although the reduction in tumor size was more notable in the metastatic sites, significant areas of tumor necrosis on pathology displayed the antiangiogenic action of sunitinib.

Rini and colleagues explored the use of preoperative therapy for surgically unresectable renal masses in a prospective study [Rini et al. 2012]. Overall, 28 patients treated with sunitinib were evaluated. The criteria for unresectability included at least one of the following: large tumor size, bulky lymphadenopathy including encasement of renal vessels or great vessels, venous tumor thrombus, or proximity to vital structures. Only patients with an ECOG performance status of 0 or 1 and adequate organ function were included. A total of 13 (45%) patients met the primary endpoint of surgical resectability. Of these, 10 patients had locally advanced nonmetastatic disease and three had metastatic disease. A nephron-sparing approach was successfully performed in nine patients with a median ischemia time of 33.5 min (range 24.5–73 min). No major postoperative complications were reported. Median follow-up time was 17 months (range 7–37 months). Among the three patients with metastatic disease, two had PD on the first follow-up imaging postoperatively and one of patients with M0 disease experienced a tumor thrombus recurrence that required surgical management 8 months later.

Although many of the prior studies rely on the RECIST to standardize treatment response, it is important to note that RECIST and WHO criteria have been broadly found to overlook minor but representative tumor responses commonly encountered with systemic therapy, as targeted therapy may increase intratumoral necrosis without significant tumor diameter reduction [Hellenthal et al. 2010]. Furthermore, other studies have demonstrated that the loss of radiographic enhancement and intratumoral density may represent more important alternatives to estimate the effect of preoperative therapy in tumor perfusion rather than reduction in tumor size [Cowey et al. 2010b].

Changing radical nephrectomy to partial nephrectomy

Increasing evidence in the literature emphasizing the relationship between chronic kidney disease and the risk of cardiovascular disease has made it even more imperative to preserve renal function while at the same time maintain good oncological control [Go et al. 2004; Herzog et al. 2011]. While already a standard of care for patients with cT1a RCC, nephron-sparing approaches have become more commonplace for increasingly complex renal masses. Moreover, imperative indications for nephron-sparing surgery in the setting of locally advanced RCC, although uncommon, may present a clinical dilemma. Examples include patients who present with bilateral synchronous masses that may require radical nephrectomies due to tumor location, size and complexity, or patients with solitary kidneys with locally advanced renal masses [Shuch et al. 2011b; Collins et al. 2014]. With the negative long-term sequelae of hemodialysis being well established, committing such patients to lifelong renal replacement therapy becomes an increasingly difficult decision. As a result, neoadjuvant systemic treatments have been naturally considered in these scenarios to increase the likelihood of success with nephron-sparing approaches in locally advanced renal masses.

In the previously mentioned study, Silberstein and colleagues investigated the feasibility of preoperative targeted therapy for the reduction of primary tumor burden in an effort to maximize nephron sparing in candidates with imperative indications [Silberstein et al. 2010]. All 12 patients were considered to have operable disease after targeted therapy with partial nephrectomy achieved in all 14 kidneys, including two bilateral concurrent partial nephrectomies. The mean warm ischemia time was 22.5 min, with a mean estimated blood loss of 318 ml, and two out of 12 patients received a blood transfusion. In addition, no postoperative dialysis was required and negative surgical margins were obtained in all final pathology specimens. Interestingly, three of the 14 renal units treated with a partial nephrectomy developed delayed urinary leaks, all of which were in patients with metastatic disease who resumed sunitinib postoperatively. Although this was an interesting study despite small numbers, it did not report how many of the 12 patients could have undergone a partial nephrectomy without any preoperative treatment.

After sunitinib treatment, Hellenthal and colleagues were able to perform laparoscopic partial nephrectomy in eight of the 20 patients included in their prospective study [Hellenthal et al. 2010]. Six patients developed grade 3 toxicity from targeted therapy, but no surgical complications were attributable to sunitinib use. Although this study also did not report the number of patients who could have had partial nephrectomy without preoperative targeted therapy, it is an important study as it also demonstrates the feasibility of preoperative sunitinib prior to surgery.

In the study by Karam and colleagues, five (21.8%) of 24 patients underwent partial nephrectomy after neoadjuvant axitinib therapy without any intraoperative or postoperative complications [Karam et al. 2014]. It is important to note that undergoing a partial nephrectomy was also not a prespecified endpoint in the study. Nevertheless, it demonstrates the feasibility of using agents other than sunitinib in the neoadjuvant setting.

Rini and colleagues reported on a study focusing on the feasibility of partial nephrectomy after targeted therapy in which 25 patients were included, and met absolute or relative indications for partial nephrectomy [Rini et al. 2015]. High-risk patients with significant chronic kidney disease or a solitary kidney were included in the study. The results showed that after a median treatment time of 8 weeks, 92% of the tumors shrank, with a significant improvement in renal nephrometry score and complexity (71% of tumors decreased in size). Overall, 17 of 25 patients underwent partial nephrectomy, including six of 13 patients in whom partial nephrectomy was not considered possible based on preoperative surgeon evaluation. The authors reported urine leak rate of 25% in patients who underwent partial nephrectomy. Even though multifactorial and likely related to the high complexity of the tumors included in this study, this study highlights that neoadjuvant targeted therapy in localized RCC should be offered to selected patients with limited options.

In the multicenter, retrospective series by Lane and colleagues, partial nephrectomy was performed on 49 kidneys after targeted therapy, with partial nephrectomy rates varying according to clinical stage: 91%, 88% and 43% for localized cT1a, cT1b and cT2–3 tumors, respectively (per post-treatment clinical stage) [Lane et al. 2015]. Two patients had a urine leak and one patient had an arteriovenous fistula after partial nephrectomy (Clavien grade 3).

Given that the utilization of feasibility of partial nephrectomy as an endpoint in clinical trials is still subjective and multifactorial, Karam and colleagues studied interobserver agreement when making such assessment [Karam et al. 2015]. Five independent investigators with expertise in urologic oncology reviewed CT scans from the neoadjuvant axitinib trial in a blinded fashion and recorded if partial nephrectomy was feasible. Not surprisingly, the odds of feasibility of partial nephrectomy markedly increased after axitinib, but identifying which patients would benefit from such therapy a priori is still not possible. In addition, the agreement on feasibility of partial nephrectomy was noted to be higher for moderate complexity tumors and lower for more complex tumors (where this endpoint is most clinically relevant).

Downstaging inferior vena cava thrombus

Traditionally, systemic therapy and radiation therapy have shown limited usefulness, and aggressive radical surgical resection with inferior vena cava (IVC) thrombectomy remains the standard of care in appropriate candidates. Despite the curative intent of surgical resection, the risks involved are not negligible, with potential for perioperative mortality among patients with a level III–IV IVC thrombus [Shuch et al. 2011a; Abel et al. 2014].

Much of the existing studies on the use of preoperative therapy in the setting of an IVC thrombus are single-center case reports (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of relevant case reports/series with preoperative therapy for the treatment of RCC with venous tumor thrombus.

| References | N | Tumor thrombus level at diagnosis | Agent | Number of cycles | Tumor thrombus after targeted therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karakiewicz et al. [2008] | 1 | IV | Sunitinib | 2 | I |

| Di Silverio et al. [2008] | 1 | II | Sorafenib | 6 months | 0 (renal vein) |

| Shuch et al. [2008] | 1 | II | Sunitinib | 4 | I |

| Harshman et al. [2009] | 1 | I | Sunitinib | 4 | 0 (renal vein) |

| Robert et al. [2009] | 1 | III | Sunitinib | 5 | III |

| Kondo et al. [2010] | 1 | II | Sorafenib | 2 | II |

| Bex et al. [2010] | 1 1 | NoneII | Sunitinib | 2 | No thrombus to new level ILevel II to IV |

| Cost et al. [2011] | 1213 | II/III/IVII/III | SunitinibBevacizumab (9), Temsirolimus (3), Sorafenib (1) | 2 (median) | 9 stable level, 1 level IV to III, 1 level III to II, 1 level II to 012 stable level, 1 level II to III |

| 2 (median) | |||||

| Horn et al. [2012] | 2 3 | IIIIV | Sunitinib | 2 | 3 stable, 1 level IV to II, 1 unclear |

| Sano et al. [2013] | 1 | III | Temsirolimus | 5 months | I |

| Sassa et al. [2014] | 1 | IV | Axitinib | 1 month | III |

| Bigot et al. [2014] | 110 3 | IIIIII | Sunitinib (11),Sorafenib (3) | 2 | 12 stable level, 1 level II to I, 1 level III to IV |

| Peters et al. [2014] | 1 | IV | Sunitinib | 4 | III |

RCC, renal cell carcinoma.

The largest retrospective study reported by Cost and colleagues comes from a multicenter effort describing the use of targeted therapy in patients treated with IVC tumor thrombi at various levels [Cost et al. 2011]. A total of 25 patients with locally advanced RCC and IVC tumor thrombus, 19 of whom had biopsy-proven clear cell RCC, underwent preoperative therapy with a median of two cycles of targeted therapy. Eighteen patients presented with level II, five with level III, and two with level IV IVC thrombus at baseline. Twelve patients received sunitinib, while the rest received bevacizumab (nine patients), temsirolimus (three patients) or sorafenib (one patient). At the conclusion of targeted therapy, 21 (84%) patients had no change in IVC tumor thrombus level, while three (12%) patients experienced downstaging in thrombus level (one level IV to level III, one level III to level II, and one level II to 0). Only one (4%) patient experienced a reduction of the thrombus level that resulted in a change of surgical strategy (from level IV to level III). One patient actually experienced an increase in the tumor thrombus level (from level II to III). Interestingly, the overall magnitude of change in IVC tumor thrombus level compared with the no-treatment group did not reach statistical significance.

Similarly, Bigot and colleagues retrospectively analyzed a multicenter series of 14 patients with clear cell RCC with IVC tumor thrombi treated with preoperative targeted therapy (median of two cycles) [Bigot et al. 2014]. A total of six (43%) patients had a measurable decrease, six (43%) experienced no change and two (14%) patients had an increase in thrombus height. Furthermore, only one patient showed significant thrombus level downstaging (level II to level I), which did not modify the surgical approach, and one patient experienced a progression of thrombus level (level III to level IV) which increased surgical morbidity.

A study by Kwon and colleagues studied the efficacy of targeted therapy and tumor thrombus response by RECIST and Choi criteria, but not using surgical thrombus classification systems, which are more relevant in this clinical setting [Kwon et al. 2014]. Twenty-two patients underwent preoperative systemic therapy (18 sunitinib, four sorafenib, median of 12 weeks). Despite the heterogeneity of the cohort, with 17 patients with M1 and 5 with M0, 18 with clear cell and four with non-clear cell RCC, nine (40.9%) patients demonstrated a PR in the IVC tumor thrombus based on Choi criteria [a decrease in size ⩾ 10% or a decrease in tumor attenuation (HU) ⩾ 15% on CT]. Moreover, Kwon and colleagues showed that this IVC tumor-response cohort of patients had a longer survival than the patients with SD: 23 versus 7.2 months, respectively (p = 0.01). However, only two (9.1%) patients achieved a PR according to RECIST. Moreover, based on multivariate regression analysis, this study displayed the Choi response in IVC tumor thrombi as the only predictive factor in patients treated with targeted therapy [Kwon et al. 2014]. Unfortunately, this study did not report on thrombus level changes using surgical classification systems, and as such, the relevance of the study from a surgical standpoint is limited.

In summary, while preoperative targeted therapy has been demonstrated to decrease primary tumor size, the overall body of literature would indicate that the same does not hold true for downstaging of IVC thrombi, as any decrease in the extent of the thrombus would have to be of such a magnitude to significantly affect the surgical approach in order to be clinically meaningful.

Conclusion

Current evidence in the literature demonstrates the potentially expanding role of preoperative targeted therapy in the management of locally advanced RCC and mRCC. Despite the antiangiogenic effect of these agents and their involvement in tissue recovery, observations indicate that presurgical targeted therapy is safe and feasible and does not significantly increase overall postoperative complications rate when used appropriately.

Studies have demonstrated that preoperative targeted therapy results in primary tumor shrinkage, with the majority of the effect occurring early in the treatment phase. Neoadjuvant therapy may sometimes be used to downstage unresectable tumors and potentially ease surgical resection. Moreover, in select patients, neoadjuvant therapy may facilitate nephron-sparing approaches. However, it seems that neoadjuvant therapy lacks consistent benefit in patients with IVC tumor thrombus.

Further work is needed to define what is truly ‘unresectable’ or ‘not amenable to partial nephrectomy’, to find predictors of response to preoperative targeted therapy and to study the most appropriate scenario to use these therapies in the preoperative setting.

At present, we do not recommend the routine use of neoadjuvant therapy in patients who otherwise have resectable disease. We recommend using them only in tertiary referral centers in the setting of clinical trials or as a last resort in very carefully selected and well informed patients after multidisciplinary discussion.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: Jose A. Karam has served as a one-time consultant to Pfizer in 2013. Christopher G. Wood has received research funding from Pfizer and served as a consultant and on its advisory board.

Contributor Information

Leonardo D. Borregales, Department of Urology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA

Mehrad Adibi, Department of Urology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Arun Z. Thomas, Department of Urology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA

Christopher G. Wood, Department of Urology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA

Jose A. Karam, Department of Urology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Unit 1373, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

References

- Abel E., Thompson R., Margulis V., Heckman J., Merril M., Darwish O., et al. (2014) Perioperative outcomes following surgical resection of renal cell carcinoma with inferior vena cava thrombus extending above the hepatic veins: a contemporary multicenter experience. Eur Urol 66: 584–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bex A., Van Der Veldt A., Blank C., Meijerink M., Boven E., Haanen J. (2010) Progression of a caval vein thrombus in two patients with primary renal cell carcinoma on pretreatment with sunitinib. Acta Oncologica 49: 520–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bex A., Van Der Veldt A., Blank C., Van Den Eertwegh A., Boven E., Horenblas S., et al. (2009) Neoadjuvant sunitinib for surgically complex advanced renal cell cancer of doubtful resectability: initial experience with downsizing to reconsider cytoreductive surgery. World J Urol 27: 533–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigot P., Fardoun T., Bernhard J., Xylinas E., Berger J., Roupret M., et al. (2014) Neoadjuvant targeted molecular therapies in patients undergoing nephrectomy and inferior vena cava thrombectomy: is it useful? World J Urol 32: 109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin B., Delacroix S., Jr, Culp S., Nogueras Gonzalez G., Tannir N., Jonasch E., et al. (2011) Safety of presurgical targeted therapy in the setting of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 60: 964–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins A., Foley R., Chavers B., Gilbertson D., Herzog C., Ishani A., et al. (2014) US renal data system 2013 annual data report. Am J Kidney Dis 63: A7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cost N., Delacroix S., Jr, Sleeper J., Smith P., Youssef R., Chapin B., et al. (2011) The impact of targeted molecular therapies on the level of renal cell carcinoma vena caval tumor thrombus. Eur Urol 59: 912–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowey C., Amin C., Pruthi R., Wallen E., Nielsen M., Grigson G., et al. (2010a) Neoadjuvant clinical trial with sorafenib for patients with stage II or higher renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 28: 1502–1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowey C., Fielding J., Rathmell W. (2010b) The loss of radiographic enhancement in primary renal cell carcinoma tumors following multitargeted receptor tyrosine kinase therapy is an additional indicator of response. Urology 75: 1108–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Silverio F., Sciarra A., Parente U., Andrea A., Von Heland M., Panebianco V., et al. (2008) Neoadjuvant therapy with sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma with vena cava extension submitted to radical nephrectomy. Urol Int 80: 451–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go A., Chertow G., Fan D., McCulloch C., Hsu C. (2004) Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization.N Engl J Med 351: 1296–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golshan M., Garber J., Gelman R., Tung N., Smith B., Troyan S., et al. (2011) Does neoadjuvant bevacizumab increase surgical complications in breast surgery? Ann Surg Oncol 18: 733–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffioen A., Mans L., De Graaf A., Nowak-Sliwinska P., De Hoog C., De Jong T., et al. (2012) Rapid angiogenesis onset after discontinuation of sunitinib treatment of renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res 18: 3961–3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harshman L., Srinivas S., Kamaya A., Chung B. (2009) Laparoscopic radical nephrectomy after shrinkage of a caval tumor thrombus with sunitinib. Nat Rev Urol 6: 338–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellenthal N., Underwood W., Penetrante R., Litwin A., Zhang S., Wilding G., et al. (2010) Prospective clinical trial of preoperative sunitinib in patients with renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 184: 859–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog C., Asinger R., Berger A., Charytan D., Diez J., Hart R., et al. (2011) Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease. A clinical update from kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 80: 572–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn T., Thalgott M., Maurer T., Hauner K., Schulz S., Fingerle A., et al. (2012) Presurgical treatment with sunitinib for renal cell carcinoma with a level III/IV vena cava tumour thrombus. Anticancer Res 32: 1729–1735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz H., Fehrenbacher L., Novotny W., Cartwright T., Hainsworth J., Heim W., et al. (2004) Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 350: 2335–2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonasch E., Wood C., Matin S., Tu S., Pagliaro L., Corn P., et al. (2009) Phase II presurgical feasibility study of bevacizumab in untreated patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 27: 4076–4081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakiewicz P., Suardi N., Jeldres C., Audet P., Ghosn P., Patard J., et al. (2008) Neoadjuvant sutent induction therapy May effectively down-stage renal cell carcinoma atrial thrombi. Eur Urol 53: 845–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karam J., Devine C., Fellman B., Urbauer D., Abel E., Allaf M., et al. (2015) Variability of inter-observer agreement on feasibility of partial nephrectomy before and after neoadjuvant axitinib for locally advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC): independent analysis from a phase II trial. BJU Int. doi: 10.1111/bju.13188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karam J., Devine C., Urbauer D., Lozano M., Maity T., Ahrar K., et al. (2014) Phase 2 trial of neoadjuvant axitinib in patients with locally advanced nonmetastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 66: 874–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T., Hashimoto Y., Kobayashi H., Iizuka J., Nishikawa T., Nakano M., et al. (2010) Presurgical targeted therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors for advanced renal cell carcinoma: clinical results and histopathological therapeutic effects. Jpn J Clin Oncol 40: 1173–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon T., Lee J., Kim J., You D., Jeong I., Song C., et al. (2014) The Choi response criteria for inferior vena cava tumor thrombus in renal cell carcinoma treated with targeted therapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 140: 1751–1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane B., Derweesh I., Kim H., O’Malley R., Klink J., Ercole C., et al. (2015) Presurgical sunitinib reduces tumor size and May facilitate partial nephrectomy in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol 33: 112.e15–112.e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters I., Winkler M., Juttner B., Teebken O., Herrmann T., Von Klot C., et al. (2014) Neoadjuvant targeted therapy in a primary metastasized renal cell cancer patient leads to down-staging of inferior vena cava thrombus (IVC) enabling a cardiopulmonary bypass-free tumor nephrectomy: a case report. World J Urol 32: 245–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posadas E., Figlin R. (2014) Kidney cancer: progress and controversies in neoadjuvant therapy. Nat Rev Urol 11: 254–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powles T., Blank C., Chowdhury S., Horenblas S., Peters J., Shamash J., et al. (2011a) The outcome of patients treated with sunitinib prior to planned nephrectomy in metastatic clear cell renal cancer. Eur Urol 60: 448–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powles T., Kayani I., Blank C., Chowdhury S., Horenblas S., Peters J., et al. (2011b) The safety and efficacy of sunitinib before planned nephrectomy in metastatic clear cell renal cancer. Ann Oncol 22: 1041–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powles T., Sarwar N., Stockdale A., Boleti E., Jones R., Protheroe A., et al. (2013) Pazopanib prior to planned nephrectomy in metastatic clear cell renal cancer: a clinical and biomarker study. J Clin Oncol 31: abstract 4508. [Google Scholar]

- Rini B., Garcia J., Elson P., Wood L., Shah S., Stephenson A., et al. (2012) The effect of sunitinib on primary renal cell carcinoma and facilitation of subsequent surgery. J Urol 187: 1548–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rini B., Plimack E., Takagi T., Elson P., Wood L., Dreicer R., et al. (2015) A phase II study of pazopanib in patients with localized renal cell carcinoma to optimize preservation of renal parenchyma. J Urol 194: 297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert G., Gabbay G., Bram R., Wallerand H., Deminiere C., Cornelis F., et al. (2009) Case study of the month. Complete histologic remission after sunitinib neoadjuvant therapy in T3b renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 55: 1477–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano F., Makiyama K., Tatenuma T., Sakata R., Yamanaka H., Fusayasu S., et al. (2013) Presurgical downstaging of vena caval tumor thrombus in advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma using temsirolimus. Int J Urol 20: 637–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassa N., Kato M., Funahashi Y., Maeda M., Inoue S., Gotoh M. (2014) Efficacy of pre-surgical axitinib for shrinkage of inferior vena cava thrombus in a patient with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol 44: 370–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuch B., Crispen P., Leibovich B., Larochelle J., Pouliot F., Pantuck A., et al. (2011a) Cardiopulmonary bypass and renal cell carcinoma with level IV tumour thrombus: can deep hypothermic circulatory arrest limit perioperative mortality? BJU Int 107: 724–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuch B., Linehan W., Bratslavsky G. (2011b) Repeat partial nephrectomy: surgical, functional and oncological outcomes. Curr Opin Urol 21: 368–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuch B., Riggs S., Larochelle J., Kabbinavar F., Avakian R., Pantuck A., et al. (2008) Neoadjuvant targeted therapy and advanced kidney cancer: observations and implications for a new treatment paradigm. BJU Int 102: 692–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberstein J., Millard F., Mehrazin R., Kopp R., Bazzi W., Diblasio C., et al. (2010) Feasibility and efficacy of neoadjuvant sunitinib before nephron-sparing surgery. BJU Int 106: 1270–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A., Rini B., Lane B., Garcia J., Dreicer R., Klein E., et al. (2009) Response of the primary tumor to neoadjuvant sunitinib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 181: 518–523; discussion 523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timsit M., Albiges L., Mejean A., Escudier B. (2012) Neoadjuvant treatment in advanced renal cell carcinoma: current situation and future perspectives. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 12: 1559–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobert C., Uzzo R., Wood C., Lane B. (2013) Adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapy for renal cell carcinoma: a survey of the Society of Urologic Oncology. Urol Oncol 31: 1316–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Veldt A., Meijerink M., Van Den Eertwegh A., Bex A., De Gast G., Haanen J., et al. (2008) Sunitinib for treatment of advanced renal cell cancer: primary tumor response. Clin Cancer Res 14: 2431–2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood C., Margulis V. (2009) Neoadjuvant (presurgical) therapy for renal cell carcinoma: a new treatment paradigm for locally advanced and metastatic disease. Cancer 115: 2355–2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Li Y., Deng J., Ji Z., Yu H., Li H. (2015) Sorafenib neoadjuvant therapy in the treatment of high risk renal cell carcinoma. PLoS One 10: e0115896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]