Abstract

Cyclophosphamide (Cy) is a prodrug that depends on bioactivation by hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes for its cytotoxicity. We evaluated the influence of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of CYP enzymes on the efficacy of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) for lymphoma. SNPs of 22 genes were analyzed in 93 patients with Hodgkin (n=52) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n=41) treated with high-dose Cy followed by autologous HCT between 2004–2012. Preparative regimens contained Cy (120mg/kg) combined with carmustine/etoposide (n=61) or Cy (6000mg/m2) with total body irradiation (n=32). Lack of complete remission as measured by pre-transplant positron emission tomography was the sole clinical factor associated with increased risk of relapse (HR 2.1). In genomic analysis, we identified a single SNP rs3211371 in exon 9 (C >T) of the CYP2B6 gene (allele designation 2B6*5) that significantly impacted patient outcomes. After adjusting for disease status and conditioning regimen, patients with CYP2B6*1/*5 genotype had a higher 2-year relapse rate (HR 3.3; 95%CI 1.6–6.5; p=0.041) and decreased overall survival (HR 13.5; 95%CI 3.5–51.9; p=0.008) than patients with wild-type allele. Patients with two hypo-functional CYP2B6 variant genotypes, *5 and *6, experienced 2-year PFS of only 11% (95%CI 1–39%) compared to 67% (95% CI 55–77%) for patients with the wild-type CYP2B6*1 allele in exon 9. Our results suggest that CYP2B6 SNPs influence the efficacy of high-dose Cy and significantly reduce the success of autologous HCT for lymphoma patients with the CYP2B6*5 variant.

INTRODUCTION

High-dose chemo/radiotherapy with autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) often cures patients with recurrent chemotherapy-sensitive lymphoma. Although most patients attain remission after autologous HCT, disease progression is the most common cause of treatment failure, affecting 30–50% of patients.[1,2] Myeloablative preparative regimens for lymphoma commonly contain the potent alkylator cyclophosphamide (Cy) in combination with carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, (BEAC), carmustine, and etoposide (CyBV) or in combination with total body irradiation (Cy/TBI).[1,3–5] Cy is a prodrug that needs to be biotransformed to its metabolite 4-hydroxycyclophosphamide (4-hydroxyCy) by hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes. 4-hydroxyCy diffuses from hepatocytes to plasma, spontaneously degrades to aldophosphamide and then to phophorodiamidic mustard and acrolein which both contributes to cytotoxicity by interferes with DNA replication.[6–8] Patients treated with high-dose Cy show a large inter-patient variability in levels of Cy (3-fold) and 4-hydroxyCy (8-fold) which could be partly due to variable expression and function of CYP enzymes. In some studies, germ-line single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in CYP2B6 enzyme significantly reduced Cy bioactivation.[8,9] However, it is unknown whether Cy pharmacogene SNPs influence the efficacy of autologous HCT for lymphoma.

METHODS

Study Design

Using prospectively collected data in the University of Minnesota Blood and Marrow Transplantation Database (clinical trial numbers NCT00345865 and NCT00005985 registered at clinicaltrials.gov), we studied 93 patients with non-Hodgkin (NHL) and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) who underwent high-dose Cy containing chemotherapy followed by autologous HCT between 2004–2012. The University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board approved transplant protocols and study design and all patients gave written informed consent and were treated in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. The myeloablative preparative regimen included CyBV (Cy 1500mg/m2/day IV x 4 days, Carmustine 300mg/m2 IV day 1 and VP16 150mg/m2 twice a day IV x 4 days) or Cy/TBI (Cy 60 mg/kg IV x 2 days plus TBI 165 cGy twice daily x 4 days) and supportive care as previously reported.[2] All patients received allopurinol and no other CYP450 inhibitors or inducers were allowed during Cy infusion. Disease status was assessed pre-transplant and 3 months post-transplant by positron emission tomography (PET) according to Chesson [10] and by post-transplant computerized tomography (CT) at day 28 and month 6, 12, and 24 months.

Genotyping

After informed consent, peripheral blood leukocytes from patients were collected and stored in liquid nitrogen. DNA was obtained from peripheral blood mononuclear cells using Qiagen DNA/RNA isolation kit. Thirty-seven SNPs in 22 genes of importance to Cy pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) were selected by using information from the PharmGKB database (https://www.pharmgkb.org/) and literature screening.(listed in Supplemental Table) Sequenom iPLEX (CA, USA) that uses MALDI-TOF-based chemistry was used to genotype all but CYP2B6 rs3211371 SNP. Taqman SNP genotyping assay (ID# C_30634242_40) was used specifically for genotyping of rs3211371 SNP. Samples (from International HapMap panel) with known genotype were used as controls.

Statistical methods

The primary endpoint was the cumulative incidence of relapse at 2 years. Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival and cumulative incidence (CI) estimates of non-relapse mortality (NRM) and relapse were calculated; multivariable Cox regression determined factors associated with outcomes.[11,12,13] Each SNP was modeled as a categorical variable by using the homozygote of the most common allele as the reference category and was adjusted for disease status (complete remission (CR) vs no CR) and conditioning regimen. If the frequency of the homozygous variant allele was < 5%, this group was combined with the heterozygous group. SNPs analyzed with minimum allele frequency of more than 10% were included in the analysis. P-values were corrected for multiple testing using the Holm method to control the family-wise error rate at 5%.[14] Analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.3) and the R genetics package (version 3.0). Median post-HCT follow-up among survivors was 4 years (range 1–8 years).

RESULTS

Gene polymorphism frequencies

Ninety-three patients with lymphoma (52 HL, 41 NHL) were evaluated for association of transplant outcomes with SNPs in 22 genes of importance to Cy PK/PD. The results of gene polymorphisms, the frequencies of wild type and variant genotypes and genes function are summarized in the supplemental table. The genotypes were similar to those reported in the literature for population of European origin in accordance with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

Patient and transplant characteristics

The median age of the entire cohort was 45 years (range 26–65). Both genders were equally represented and 90% were Caucasian (Table 1). Patients with NHL received Cy/TBI regimen (n=31) or CyBV (n=9); all 52 HL patients received CyBV (Table 1). Median time from diagnosis to HCT was 15 months (range 4–236 months). Most patients (94%) were chemosensitive and 59% were PET negative prior to transplant (Table 1). Only 4 patients were chemoresistant, all had HL.

Table 1.

Patient and transplant characteristics by CYP2B6 polymorphism

| All patients n (%) |

CYP2B6*1/*1 n (%) |

CYP2B6*1/*5 n (%) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 92 (100) | 71 (100) | 21 (100) | |

| Median Age, Range | 45, 5–71 | 45, 5–71 | 46, 10–69 | 0.20 |

| Male Gender | 51 (55) | 38 (54) | 13 (62) | 0.62 |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 83 (90) | 64 (90) | 19 (90) | 0.29 |

| Other | 9 (10) | 7 (10) | 2 (10) | |

| Karnofsky Performance Score | 0.30 | |||

| 80–90% | 47 (51) | 38 (54) | 9 (43) | |

| 100% | 41 (45) | 31 (44) | 10 (48) | |

| Lymphoma Type | ||||

| Hodgkin | 52 (57) | 43 (61) | 9 (43) | 0.21 |

| Non-Hodgkin | 40 (43) | 28 (39) | 12 (57) | |

| Follicular | 4 (4) | 4 (6) | 0 (0) | |

| Diffuse large B-cell | 20 (22) | 12 (17) | 8 (38) | |

| Mantle cell | 12 (13) | 9 (13) | 3 (14) | |

| T-cell | 3 (3) | 2 (3) | 1 (5) | |

| Not otherwise classified | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Disease Status | ||||

| CR1a/PR1 | 19/1 (22) | 12/1 (18) | 7/0 (33) | 0.91 |

| ≥CR2 | 35 (38) | 30 (42) | 5 (24) | |

| Induction failure sensitive | 11 (12) | 8 (11) | 3 (14) | |

| ≥Partial remission 2 sensitive | 22 (24) | 16 (23) | 6 (29) | |

| Chemotherapy resistantb | 4 (4) | 4 (6) | 0 (0) | 0.57 |

| Conditioning | ||||

| Cy/Carmustine/etoposide | 61 (66) | 51 (72) | 10 (48) | 0.06 |

| Cy/Total body irradiation | 31 (34) | 20 (28) | 11 (52) | |

| Graft source | ||||

| Marrow +/− peripheral blood | 14 (15) | 9 (13) | 5 (24) | 0.30 |

| Peripheral blood | 78 (85) | 62 (87) | 16 (76) | |

| Median months from diagnosis to HCT, range | 15, 4–236 | 17, 5–138 | 14, 4–236 | 0.42 |

| Median follow-up years, Range | 3.9, 1.0–8.4 | 3.5, 1.0–8.4 | 5.2, 2.0–8.4 | 0.05 |

CR1 patients had MCL (n=10), transformed lymphoma (n=4) and Hodgkin lymphoma (n=4).

all patients with chemoresistant disease had Hodgkin lymphoma. Demographic factors were compared between 2B6*5 and wild type 2B6*1*1 genotypes using Fisher’s exact test for categorical factors and two-sided Wilcoxon test for continuous factors.

Abbreviations: Cy cyclophosphamide, PBSC peripheral blood stem cells HCT hematopoietic cell transplantation, PR partial remission

Transplant outcomes

We first studied the impact of clinical variables age, gender, performance status, lymphoma subtype, disease status pre-transplant, conditioning type, graft source and time from diagnosis to transplant on relapse and progression-free survival (PFS) in univariate analysis (Table 2). As expected, pre-transplant disease status other than CR significantly increased risk of relapse (HR 2.1; p=0.02). Other factors such as age, gender, lymphoma histology, conditioning regimen, pre-transplant performance status, and interval from diagnosis to transplant did not influence relapse or PFS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate associations of demographic factors with 2-year relapse

| Factor | Relapse Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Age (per 10 year increase) | 1.0 (0.8 – 1.2) | .78 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1.0 | |

| Female | 0.7 (0.3 – 1.3) | .25 |

| Karnofsky Performance Score | ||

| 80–90% | 1.0 (0.5 – 2.0) | .93 |

| 100% | 1.0 | |

| Lymphoma Type | ||

| Hodgkin | 1.0 | |

| Diffuse large B-cell | 1.1 (0.5 – 2.4) | .78 |

| Mantle cell | 0.6 (0.2 – 1.9) | .35 |

| Disease Status prior to HCT | ||

| In CR by PET | 1.0 | |

| Not in CR | 2.1 (1.1 – 4.1) | .02 |

| Conditioning | ||

| Cy/Carmustine/etoposide | 1.0 | |

| Cy/Total body irradiation | 0.7 (0.3 – 1.3) | .25 |

| Graft source | ||

| Marrow +/− PBSC | 1.0 (0.4 – 2.5) | .95 |

| PBSC | 1.0 | |

| Months from diagnosis to HCT (per 1 month increase) | 1.0 (1.0 – 1.0) | .99 |

| CYP2B6 | ||

| *1/*1 | 1.0 | |

| *1/*5 | 2.8 (1.4 – 5.4) | < .01 |

Abbreviations: CR complete remission, PET positron emission tomography, HCT hematopoietic cell transplantation, PBSC peripheral blood stem cells, Cy cyclosphospamide

Relapse and survival by CYP polymorphism

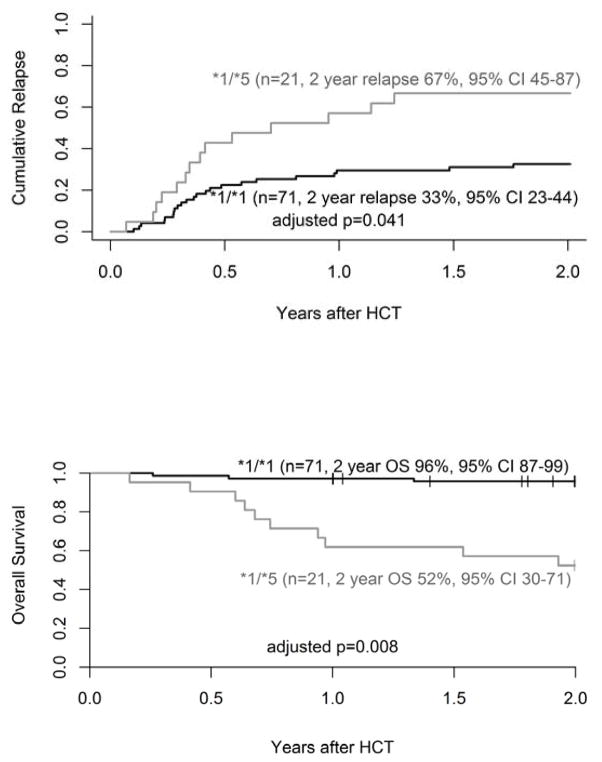

We identified a single SNP rs3211371 in exon 9 (C >T) of the CYP2B6 gene (allele designation 2B6*5) that significantly affected transplant outcomes. Twenty-one patients (23%) were heterozygous (CYP2B6*1/*5; CT genotype) and 71 (76%) were wild-type for rs3211371 (CYP2B6*1/*1; CC genotype). One individual was excluded because of failed genotyping. Patient age, gender, and race (>90% Caucasian) were similar between the two genotype groups (CYP2B6*1/*1 vs. CYP2B6*1/*5; Table 1). Most patients in both groups were in CR (61% and 62%) pre-transplant by PET imaging. Patients with a variant CYP2B6*5 more often had NHL, Cy/TBI conditioning and chemosensitive lymphoma; wild type cohort had more HL patients including 4 with chemotherapy refractory disease (Table 1). After adjusting for disease status (CR vs. no CR) and conditioning regimen, the 2-year cumulative incidence of relapse was significantly higher with the CYP2B6*1/*5 variant (67%; 95%CI 45–87) compared to the wild-type CYP2B6*1/*1 (33%; 95%CI 23–44; p=0.041). As a result, adjusted PFS was inferior in CYP2B6*1/*5 compared to the wild-type CYP2B6*1/*1 group (HR 3.3; 95% CI 1.6–6.5; p=0.001; adjusted p=0.041) and 2-year OS decreased to 52% (95%CI 30–71) in CYP2B6*1/*5 patients versus 96% (95%CI 87–99; p= 0.008; Figure 1A, 1B) in wild-type group. Both NHL and HL cohorts yield worse prognosis with CYP2B6*1/*5 variant compared to wild genotype (PFS: NHL 33% vs 68%; HL 22% vs 73%).

FIGURE 1.

Two-year cumulative incidence of relapse (A) and overall survival (B) in adults with lymphoma by CYP2B6 genotype. Hazard ratios are adjusted for disease status and conditioning. P-values are adjusted for multiple tests using Holm’s method. *1/*1 represents the wild-type allele.

Notably, all 8 non-CR patients with the CYP2B6*1/*5 genotype relapsed at a median of 5 months post-transplant compared to 12 out of 28 non-CR patients with the wild-type genotype. Furthermore, patient with both the CYP2B6*6 allele (carriers of rs3745274 and rs2279343 on exon 4 and 5) and CYP2B6*1/*5 genotype (n=9) had a 2-year PFS of only 11% (95%CI 1–39%) compared to 67% (95% CI 55–77%) for 71 patients who expressed the wild-type CYP2B6*1/*1 allele in exon 9.

We collected targeted Cy-associated toxicities and observed no grade 4 adverse events or deaths due cardiotoxicity, veno-occlusive liver disease and hemorrhagic cystitis. There was no NRM within 2 years.

DISCUSSION

We report a novel association between a germ-line CYP2B6*5 polymorphism and reduced efficacy of high-dose Cy-containing chemotherapy in lymphoma. CYP2B6 is the predominant enzyme that activates Cy at higher concentrations.[8,15] In autologous HCT, the preparative regimen which consist of high-dose chemotherapy and/or TBI is administered with rationale to eliminate the malignant disease. The Cy dose used in myeloablative preparative regimens is at its extreme and is tolerable only if combined with autologous stem cell rescue to support hematopoiesis. Helsby et al. recently showed reduced conversion of Cy in human liver microsomes with the CYP2B6*5 C>T SNP variant in vitro.[15] By testing recombinant CYP2B6 enzymes, the *5 variant expressed lower levels of CYP2B6 protein and resulted in 50% less 4-hydroxyCy compared to the wild-type variant.[8,15] Our results suggest that individuals with the germ-line CYP2B6*5 variant respond poorly to very high-dose Cy-containing therapy. High relapse and inferior survival after a Cy-containing preparative regimen can be explained, at least in part, by decreased biotransformation to 4-hydroxy-Cy, aldophosphamide and its products phophorodiamidic mustard and acrolein with subsequent loss of anti-lymphoma activity.

Whereas several groups have examined the clinical impact of CYP allelic variations in allogeneic donor HCT [6,16–18], there is lack of studies examining autologous HCT where the response is entirely dependent of potent chemotherapy. In allogeneic sibling transplant recipients with leukemia, Rocha et al. studied pharmacogenes polymorphisms [16] and found that CYP2B6 family particularly *2A and *6 were associated with mucositis, hemorrhagic cystitis and venoocclusive liver disease; however the events frequency was quite low. Furthermore, relapse rate in this study was low (10%) to recognize the differential impact of pharmacogene polymorphism on leukemia control. In another study, Black et al. found that CYP2B6*5 was associated with less toxicity <100 days after transplantation and modestly increased relapse risk after myeloablative Cy/TBI allogeneic donor HCT for acute leukemia [17]. It is notable that despite substantial differences in this and our study, these results are consistent with ours and support poor in vivo bioactivation of Cy in patients with the CYP2B6*5 SNP. Melanson et al. examined allogeneic HCT recipients with mixed diagnosis and showed no difference in NRM and worse PFS in CYP2B6*1/*4 and *4/*5 recipients; however, the CYP2B6*5 and *1/*1 (wild-type) gentoypes were combined into a single category and therefore the influence of individual alleles was not reported [18]. The complex nature of the CYP2B6 haplotypes generated by combination of the SNPs, allele designation based on co-occurrence of multiple SNPs and inconsistencies among reported studies on the CYP allele nomenclature all limit the value of study comparisons.[19–21]

Several conditioning regimens have been evaluated for lymphoma, some do not contain Cy (eg, carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan; BEAM). Two recent studies reported that BEAM regimen yield better PFS (58%) compared to Cy/TBI (31%) or CyBV (40%); however comparisons are retrospective and include historical cohorts.[5,22] Differences in efficacy possibly can be related to CYP2B6*5 polymorphism occurring in 9–14% of Caucasian, and 2–9% of African American. German CLL group recently reported lower response rates in patients with the CYP2B6*6 genotype compared to wild-type after Cy, fludarabine, and rituximab for chronic lymphocytic leukemia.[23] CYP2B6 polymorphisms occur in about 10–40% of Caucasians with CYP2B6*6 being the most frequent followed by CYP2B6*5.[9] In our series, about 10% of patients had both CYP2B6*5 and CYP2B6*6 allelic variants, and relapse among these patients was particularly high, suggesting a detrimental effect on CYP2B6 function.

Limitations of our study include smaller sample size and limited number of patients in each histology group; therefore, the validation in larger study in patients receiving high-dose Cy is warranted. The ease and portability of Taqman SNP genotyping assay for 2B6*5 would allow for implementation to clinic. While the prospective study correlating CYP2B6*5 SNP and Cy metabolite levels is underway at our center, our observations suggest that individualized Cy dosing based on CYP genotype could be applied in the future. Alternatively, conditioning, such as BEAM, may be preferable in transplant candidates having an adverse CYP2B6*5 polymorphism. Given many anti-cancer and immunosuppressive applications of Cy, for example post-transplant Cy use in haplo-identical HCT; our results may have broader clinical implications.[21]

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award Number UL1TR000114 (VB). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported in part by NIH P30 CA77598 utilizing the Biostatistics and informatics core, Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota shared resource. JKL is supported by NIH R01-CA132946 and R21-CA155524. We would like to thank Julie Curtsinger from University of Minnesota Cancer Center Translational Therapy Lab for assistance with blood samples retrieval and Michael Franklin for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

AUTHORSHIP AND CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflict of interest: Authors declare no competing financial interests.

V. B. - designed the study, collected and verified patient information, analyzed and interpreted data and wrote manuscript

R.S.-performed statistical analysis, wrote and approved the manuscript

F. M. – reviewed patients data and assisted in data interpretation and manuscript writing

L.C- performed DNA isolation and genotyping assays, helped in data interpretation and analysis

V.L – designed and selected candidate genes and SNPs for genetic study, verified the genotyping data and helped in interpretation of the data.

D.J.W; L.J.B. - interpreted data and critically reviewed the manuscript

J.K.L – designed and selected the genetic section of the study, verified the genotyping data, analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote manuscript.

References

- 1.Vose JM, Carter S, Burns LJ, et al. Phase III randomized study of rituximab/carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan (BEAM) compared with iodine-131 tositumomab/BEAM with autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results from the BMT CTN 0401 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1662–1668. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lerner RE, Thomas W, Defor TE, Weisdorf DJ, Burns LJ. The International Prognostic Index assessed at relapse predicts outcomes of autologous transplantation for diffuse large-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in second complete or partial remission. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.12.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gisselbrecht C, Schmitz N, Mounier N, et al. Rituximab maintenance therapy after autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients with relapsed CD20(+) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: final analysis of the collaborative trial in relapsed aggressive lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4462–4469. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.9416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Philip T, Guglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation as compared with salvage chemotherapy in relapses of chemotherapy-sensitive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1540–1545. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512073332305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.William BM, Loberiza FR, Jr, Whalen V, et al. Impact of conditioning regimen on outcome of 2-year disease-free survivors of autologous stem cell transplantation for hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2013;13:417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie H, Griskevicius L, Stahle L, et al. Pharmacogenetics of cyclophosphamide in patients with hematological malignancies. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2006;27:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takada K, Arefayene M, Desta Z, et al. Cytochrome P450 pharmacogenetics as a predictor of toxicity and clinical response to pulse cyclophosphamide in lupus nephritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2202–2210. doi: 10.1002/art.20338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raccor BS, Claessens AJ, Dinh JC, et al. Potential contribution of cytochrome P450 2B6 to hepatic 4-hydroxycyclophosphamide formation in vitro and in vivo. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40:54–63. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.039347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thorn CF, Lamba JK, Lamba V, Klein TE, Altman RB. PharmGKB summary: very important pharmacogene information for CYP2B6. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2010;20:520–523. doi: 10.1097/fpc.0b013e32833947c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheson BD. New staging and response criteria for non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma. Radiol Clin North Am. 2008;46:213–23. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan ELMP. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin DY. Non-parametric inference for cumulative incidence functions in competing risks studies. Stat Med. 1997;16(8):901–910. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970430)16:8<901::aid-sim543>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J Royal Stat Soc B. 1972;(34):187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1979;6(2):65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helsby NA, Hui CY, Goldthorpe MA, et al. The combined impact of CYP2C19 and CYP2B6 pharmacogenetics on cyclophosphamide bioactivation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:844–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03789.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rocha V, Porcher R, Fernandes JF, et al. Association of drug metabolism gene polymorphisms with toxicities, graft-versus-host disease and survival after HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for patients with leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23:545–556. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Black JL, Litzow MR, Hogan WJ, et al. Correlation of CYP2B6, CYP2C19, ABCC4 and SOD2 genotype with outcomes in allogeneic blood and marrow transplant patients. Leuk Res. 2012;36:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melanson SE, Stevenson K, Kim H, et al. Allelic variations in CYP2B6 and CYP2C19 and survival of patients receiving cyclophosphamide prior to myeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am J Hematol. 2010;85:967–971. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zanger UM, Klein K. Pharmacogenetics of cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6): advances on polymorphisms, mechanisms, and clinical relevance. Front Genet. 2013;4:24. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ekhart C, Doodeman VD, Rodenhuis S, Smits PH, Beijnen JH, Huitema AD. Influence of polymorphisms of drug metabolizing enzymes (CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, GSTA1, GSTP1, ALDH1A1 and ALDH3A1) on the pharmacokinetics of cyclophosphamide and 4-hydroxycyclophosphamide. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2008;18:515–523. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282fc9766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helsby NA, Tingle MD. Which CYP2B6 variants have functional consequences for cyclophosphamide bioactivation? Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40:635–637. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.043646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salar A, Sierra J, Gandarillas M, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for clinically aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: the role of preparative regimens. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;27:405–412. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson GG, Lin K, Cox TF, et al. CYP2B6*6 is an independent determinant of inferior response to fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2013;122:4253–4258. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-516666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.