Abstract

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) is a prevalent and dangerous phenomenon associated with many negative outcomes, including future suicidal behaviors. Research on these behaviors has primarily focused on correlates; however, an emerging body of research has focused on NSSI risk factors. To provide a summary of current knowledge about NSSI risk factors, we conducted a meta-analysis of published, prospective studies longitudinally predicting NSSI. This included 20 published reports across 5078 unique participants. Results from a random-effects model demonstrated significant, albeit weak, overall prediction of NSSI (OR = 1.59; 95% CI: 1.50 to 1.69). Among specific NSSI risk factors, prior history of NSSI, cluster b, and hopelessness yielded the strongest effects (ORs > 3.0); all remaining risk factor categories produced ORs near or below 2.0. NSSI measurement, sample type, sample age, and prediction case measurement type (i.e., binary versus continuous) moderated these effects. Additionally, results highlighted several limitations of the existing literature, including idiosyncratic NSSI measurement and few studies among samples with NSSI histories. These findings indicate that few strong NSSI risk factors have been identified, and suggest a need for examination of novel risk factors, standardized NSSI measure ment, and study samples with a history of NSSI.

Keywords: Self-injury, NSSI, Risk factor, Meta-analysis, Longitudinal, Prediction

1. Introduction

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) is defined as direct and deliberate self-harm enacted without the desire to die (most often self-cutting; Nock, 2010). Lifetime prevalence rates of these behaviors range from 5.5–17% in community samples (among teens and adults respectively; Swannell, Martin, Page, Hasking, & St. John, 2014) and 50% in clinical samples (DiClemente, Ponton, & Hartley, 1991; Penn, Esposito, Schaeffer, Fritz, & Spirito, 2003). In addition to being dangerous in its own right, NSSI may be a risk factor for future suicidal behaviors (e.g., Asarnow et al., 2011; Bryan, Bryan, Ray-Sannerud, Etienne, & Morrow, 2014; *Cox et al., 2012; Goldstein et al., 2012; Whitlock et al., 2013; *Wilkinson, Kelvin, Roberts, Dubicka, & Goodyer, 2011; Guan, Fox, & Prinstein, 2012). Given the dangerousness and prevalence of these behaviors, it is concerning that no intervention has been consistently shown to reduce NSSI compared to an active control group (see Brausch & Girresch, 2012; Glenn, Franklin, & Nock, 2015; Gonzales & Bergstrom, 2013; Nock, 2010; Washburn et al., 2012). These findings indicate that existing treatments do not target the processes that drive NSSI. The primary purpose of the present meta-analysis was to evaluate risk factors for NSSI, with the aim of providing a foundation for advancing the understanding and treatment of NSSI.

Before exploring these risk factors in more detail, it is necessary to differentiate risk factors from correlates (Kraemer et al., 1997). Correlates are associated with a given outcome, but the specific nature of this association is ambiguous. For example, if emotion dysregulation co-occurred with NSSI, emotion dysregulation would be a correlate of NSSI and it would be unclear how or why they were related. Risk factors, in contrast, temporally precede the outcome of interest and divide individuals into high and low risk groups (Kraemer et al., 1997). If emotion dysregulation preceded NSSI and distinguished those who would engage in future NSSI from those who would not, emotion dysregulation would also be a risk factor for NSSI. Causal risk factors are a specific type of risk factor that can be especially useful for prediction, theory development, and establishing treatment targets. Causal risk factors can be manipulated to change the probability that an outcome will occur. If emotion dysregulation were a causal risk factor, increases or decreases in emotion dysregulation would lead to subsequent increases or decreases in the likelihood of future NSSI. The majority of research on NSSI has focused on correlates (i.e., cross-sectional associations with NSSI), but in recent years there has been a proliferation of NSSI risk factor studies (i.e., longitudinal prediction of NSSI). Very few studies have examined causal risk factors for NSSI, so the present meta-analysis will focus more specifically on NSSI risk factors.

NSSI risk factor research has focused primarily on the ability of internalizing symptoms (e.g., depression, hopelessness, anxiety), affect dys-regulation, and prior self-injurious thoughts and behaviors (including both suicidal and nonsuicidal behaviors) to predict future NSSI. Research on these factors reflects many of the most popular current theories, which link NSSI to emotional problems (especially affect dys-regulation and depressive symptoms) and other forms of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. For example, some theories suggest that people may choose to engage in NSSI to cope with internalizing symptoms (Nixon, Cloutier, & Aggarwal, 2002) and to decrease feelings of numbness or emptiness (Peterson, Freedenthal, Sheldon, & Andersen, 2008). Consistent with these theories, internalizing symptoms have been linked to NSSI in numerous studies, with cross-sectional research demonstrating higher levels of depression and anxiety (e.g., Selby, Bender, Gordon, Nock, & Joiner, 2012; Gollust, Eisenberg, & Golberstein, 2008; Nock, Joiner, Gordon, Lloyd-Richardson, & Prinstein, 2006) as well as disordered eating (e.g., Paul, Schroeter, Dahme, & Nutzinger, 2014) among individuals with a history of NSSI. Extending this research, numerous studies have examined the longitudinal association between NSSI and internalizing symptoms, with a specific focus on depression, anxiety, and eating disorders.

Regarding affect dysregulation, the majority of NSSI theories propose that emotion dysregulation is a central component in understanding why people engage in NSSI (e.g., Chapman, Gratz, & Brown, 2006; Brown, Comtois, & Linehan, 2002; Selby & Joiner, 2009). According to these theories, people who engage in NSSI have particularly high levels of emotion dysregulation, and these feelings drive them to engage in NSSI as a way to improve their mood. The hypothesized mechanisms through which this affect regulation occurs varies (e.g., painful distraction redirecting attention, Chapman et al., 2006; disruption of ruminative processes, Selby & Joiner, 2009), but the conclusion is the same: people engage in NSSI (or other impulsive behaviors such as binge drinking) because they have labile emotions, and these behaviors then serve to regulate their emotions. Cross-sectional research examining this theory has been mixed. Regarding self-report studies, people who engage in NSSI demonstrate higher levels of self-reported emotion dys-regulation (e.g., Glenn, Blumenthal, Klonsky, & Hajcak, 2011; Nock, Wedig, Holmberg, & Hooley, 2008; Franklin, Lee, Puzia, & Prinstein, 2013) and negative affect (e.g., Bresin, 2014; Victor & Klonsky, 2014) than those who do not. However, experimental (e.g., Franklin et al., 2010; Kaess et al., 2012; Weinberg & Klonsky, 2012; Bresin & Gordon, 2013) and psychophysiological studies (e.g., Franklin et al., 2010; Glenn et al., 2011; Kaess et al., 2012) have often failed to reveal this pattern.

In contrast to these mixed findings, a large body of research has revealed that the majority of people who engage in NSSI report that doing so helps them to feel better, and this finding has been demonstrated across self-report, experimental, and psychophysiological measures (e.g., Nock & Prinstein, 2004; Brown et al., 2002; Bresin & Gordon, 2013; Franklin et al., 2010, 2013a; Russ et al., 1992; Weinberg & Klonsky, 2012). Together, this work suggests that mood improvement may be a central function of NSSI engagement. Extending these findings, emerging research has examined longitudinal associations between NSSI and numerous types of self-reported affect dysregulation, such as emotional suppression, emotional reactivity, and negative affect.

Finally, previous behavior is often one of the strongest predictors of future behavior. Accordingly, many researchers have examined whether a history of NSSI is predictive of future NSSI. This is an especially important risk factor to examine in conjunction with other factors to help discern the unique importance of a given factor above and beyond a history of these behaviors. Moreover, a large body of research has demonstrated that NSSI and suicidal thoughts and behaviors are highly comorbid (e.g., Lloyd-Richardson, Perrine, Dierker, & Kelley, 2007; Tang et al., 2011; Brunner et al., 2007; MacLaren & Best, 2010). Extending upon research examining NSSI as a risk factor for future suicidal behaviors, researchers have also examined whether these thoughts and behaviors are predictive of future NSSI.

In addition to these more frequently studied variables, researchers have also examined many additional potential NSSI risk factors. These less frequently studied factors include borderline personality disorder, externalizing symptoms (e.g., aggression, conduct problems), impulsivity, patient prediction (i.e., self-reported likelihood of engaging in NSSI in the future), and gender. The principal goal of the present meta-analysis was to summarize this burgeoning NSSI risk factor literature. To accomplish this, we addressed three basic questions within the NSSI risk factor literature.

1.1. Question 1: what are the basic characteristics of this literature?

We examined descriptive characteristics of NSSI risk factor studies to shed light on the types of studies that have been conducted and to investigate potential strengths and gaps in the literature. Specifically, we examined the number of NSSI risk factor studies, variation in NSSI measures, follow-up lengths, and sample characteristics (i.e., sample age, history of psychopathology, and NSSI frequency over the follow-up period).

1.2. Question 2: what is the overall effect size for risk factors of NSSI and are there any especially strong risk factors?

To summarize the findings across NSSI risk factor studies, we estimated the magnitude of the overall combined effect of all risk factors and the magnitudes of each individual risk factor category. We employed meta-analytic methods for this estimation because risk factor magnitudes vary substantially across studies. For example, *Prinstein and colleagues (2010) found that depressive symptoms strongly and significantly predicted future engagement in NSSI among adolescents; however, *Hankin and Abela (2011) did not find a significant association. Considering findings in isolation makes it difficult to determine the true magnitude of a risk factor. Meta-analytic methods overcome this limitation by combining results across studies using dynamic weighting procedures.

Clinicians are often asked to assess whether their clients are at heightened risk for engaging in future self-harming behaviors. For a variety of reasons (e.g., stigma, fear, parental consequences, longer hospital stays), some clients may be unwilling to disclose that they want or plan to engage in NSSI in the future. However, it remains important for clinicians to accurately identify clients at high risk of engaging in these behaviors to better tailor treatment and prevention efforts for those clients (e.g., asking parents to help get rid of razors and scissors around the home; ensuring clients are closely monitored when receiving inpatient care). Similarly, screening measures that can be administered on a large-scale in school or other settings could be especially helpful at identifying individuals at risk and then funneling treatment and prevention resources to those who most need them.

Accordingly, in addition to looking at the magnitude of these risk factors, we also considered their clinical utility. We defined clinical utility as the degree to which a given factor increases the absolute odds of engaging in NSSI. The prevalence rate for engaging in NSSI over a one-year period is approximately 0.9% among adults (Klonsky, 2011). Accordingly, the absolute odds of an adult engaging in NSSI any given year is .009, meaning approximately one in every 100 adults will engage in NSSI in a one-year period. If a risk factor has a weighted odds ratio of two, this factor would double the odds of next-year NSSI engagement to two in every 100 adults. In contrast, if that factor had a weighted odds ratio of 10, it would increase the odds ten-fold, resulting in next-year NSSI engagement in approximately nine of every 100 adults. To our knowledge, there is no cross-national study of past year prevalence rates of NSSI among child and adolescent populations, but rates in these populations are likely 2–3 times higher than in adult populations (Swannell et al., 2014). As such, the same risk factor magnitude may imply higher clinical utility in an adolescent sample compared to an adult sample.

1.3. Question 3: what factors moderate the associations between risk factors and NSSI?

The effect of a risk factor may change in important ways under different conditions. In the present meta-analysis, we examined four potential moderators of NSSI risk factor magnitude. The first moderator was NSSI measurement type. Measures of NSSI are highly variable across studies, with NSSI assessments ranging from single-item open-ended questions to extensive questionnaires, checklists, and interviews. Some checklists include indirect methods of self-harm (e.g., self-poisoning, substance ingestion) and normative behaviors (e.g., picking at a wound; Lloyd-Richardson et al., 2007) whereas others exclude these types of behaviors. Still other researchers include only new instances of NSSI, excluding those individuals who engaged in NSSI at baseline. This high variability in the content assessed across NSSI measures raises concerns about the validity and reliability of results and compromises the ability to make inferences across studies. In the present meta-analysis, this heterogeneity precluded tests of moderation by specific measures due to the very small number of studies employing any one measurement tool. Instead, we examined moderation across binary (i.e., grouping NSSI engagement into “yes” versus “no” categories) or continuous (i.e., assessing NSSI frequency using interval or ratio scales) measures of NSSI. We expected that binary measurement of NSSI would produce weaker prediction, as it may not sufficiently assess important features of NSSI behavior (e.g., behavior frequency, severity) that may improve predictive power.

Second, we examined study population as a moderator. NSSI risk factors studies have included general samples (i.e., participants were not selected for psychopathology or NSSI history), clinical samples (i.e., participants were selected based on a history of psychopathology), and NSSI samples (i.e., participants were selected based on a history of NSSI). We hypothesized that general sample studies would produce the strongest NSSI prediction. This is because when self-injurers are compared to other self-injurers, there are relatively few differences between the two groups other than the potential risk factor. As a result, any observed effects would be specific to the risk factor under investigation. However, when self-injurers are compared to non-injurers (especially from a general sample), there are many differences between the groups besides the potential risk factor. In those cases, psychopathology, self-injury history, and other confounding factors may combine with the risk factor under investigation to produce larger observed effects.

Third, we explored the effects of sample age. Based on current literature, it was unclear whether prediction would be stronger for adult or adolescent samples. As such, these analyses were exploratory.

Fourth, we examined the impact of the type of measure (i.e., binary versus continuous) used to predict NSSI. Importantly, odds ratios are linked to measurement scales and should be interpreted as such. Specifically, an odds ratio reflects the change in odds per one unit of measurement. Binary measures only have one unit (i.e., yes versus no), whereas continuous measures have a wide range. Accordingly, odds ratios from binary measures tend to be larger. We hypothesized that binary prediction cases would result in larger odds ratio magnitudes than continuous prediction cases.

2. Method

2.1. Study retrieval and selection

For the purposes of the present meta-analysis, NSSI was defined as any intentional act of self-harm enacted without the desire to die. To be included, we required that papers include longitudinal prediction of NSSI in any population, country, and year, using any predictor variable prior to January 1st, 2015. We identified studies by searching on PubMed, PsycInfo, and Google Scholar. To provide the most comprehensive meta-analysis possible, we included a wide range of search terms. This is especially important because research examining intentional self-harm without suicidal desire has used many different terms to describe these behaviors, including deliberate self-harm (DSH), self-mutilation, and NSSI. Moreover, studies primarily focusing on suicidal thoughts and behaviors may include measures of NSSI without mentioning NSSI in the abstract or as a keyword. Search terms included combinations of the following key words: longitudinal, longitudinally, predicts, prediction, prospective, prospectively, future, later, and self-injury, suicidality, self-harm, suicide, suicidal behavior, suicide attempt, suicide death, suicide plan, suicide thoughts, suicide ideation, suicide gesture, suicide threat, self-mutilation, self-cutting, cutting, self-burning, self-poisoning, deliberate self-harm, DSH, nonsuicidal self-injury, and NSSI. Although we used a range of search terms to identify articles, only research examining longitudinal predictors of self-harm without suicidal intent were included.

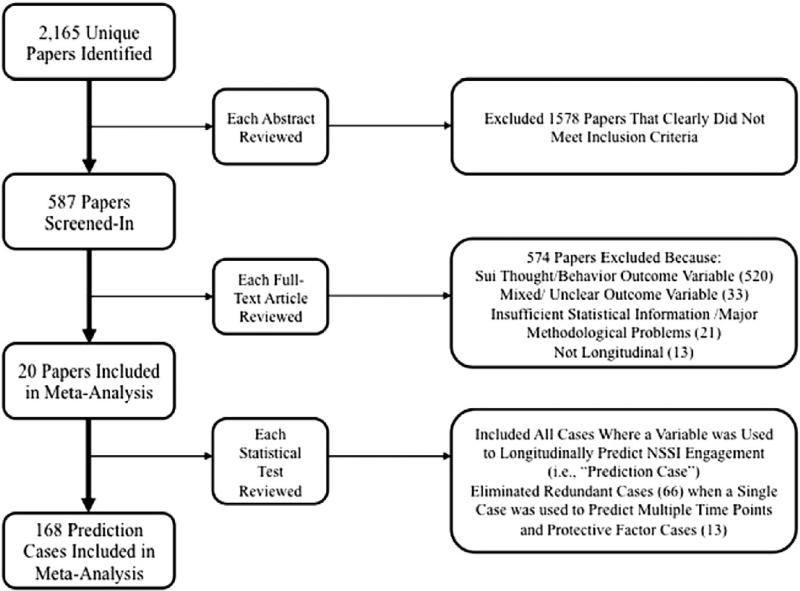

Through this process, we identified 2165 unique published reports. We read abstracts for each of these reports and excluded 1578 that clearly did not meet our inclusion criteria. We then read the full texts of the remaining 587 published reports to determine their eligibility (see Fig. 1). Studies were excluded for the following reasons: (1) outcome variables included suicidal thoughts or behaviors (n = 520); (2) self-harm with and without suicidal intent were lumped into one variable (n = 33); (3) analyses were not longitudinal or assessment of lifetime NSSI occurred only at the follow-up assessment, obscuring whether NSSI engagement occurred before or after baseline (n = 13); and (4) necessary statistical information was not available (discussed in more detail below; n = 14) or there were major methodological issues (n = 4; e.g., very different NSSI definitions across publications using the same sample; later time points mixed old and new participants, thereby casting doubt on whether findings were truly longitudinal).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

A total of 20 published reports met inclusion criteria. Seven reports included overlapping study samples, and one report included two separate studies with unique samples. In reports where males and females were analyzed separately (four reports drawn from two unique samples), the male and female samples were considered unique samples. These twenty reports each provided one or more prediction cases, which we defined as any instance where a variable was used to longitudinally predict NSSI in a given report. We removed non-unique prediction cases (i.e., prediction cases from the same sample in different published reports) and prediction cases that were hypothesized to decrease NSSI (protective factors; n = 13 prediction cases). Among reports including multiple follow-up time points, we included prediction cases for the longest time point to minimize redundancy and dependency of data and because these represented the most inclusive data points. In total, 168 prediction cases were analyzed.

2.2. Data extraction and study coding

Study authors examined each report and coded all eligible prediction cases. Errors and discrepancies were discussed and corrected, and agreement was reached among lead and co-authors. To meaningfully synthesize results across the 168 prediction cases, each case was sorted into one of 34 risk factor categories (see Table 3). We also coded the following characteristics in each study: (a) authors and year of study publication, (b) sample age (i.e., mean age, age range), (c) sample age group (samples were coded as “adolescent” when participants were below age 18 and “adult” when participants were above age 18 at the baseline assessment), (d) sample population (samples were coded as “NSSI history” when all members had a history of NSSI, “higher-risk” when members had a history of or potential risk for psychopathology, and “general”), (e) NSSI measurement (i.e., binary or continuous outcome measure), (f) follow-up length in months, (g) relevant study statistics (e.g., zero-order correlation coefficient for a prediction case), (h) whether cases were binary or continuous, and (i) whether variables were expected to predict greater or fewer NSSI episodes (i.e., risk or protective factors).

Table 3.

Risk factor categories.

| Risk factor category | # cases | # unique samples | % of cases that are binary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abuse | 4 | 2 | 75.0% |

| ADHD | 3 | 3a | 33.3% |

| Affect dysregulation | 7 | 6 | 0% |

| Age1 | 7 | 6 | 0% |

| Anxiety | 6 | 5 | 33.3% |

| Bipolar disorder | 1 | 1 | 100% |

| Childhood adversities | 4 | 1 | 25% |

| Cluster b personality | 3 | 3 | 66.7% |

| Depression | 13 | 11 | 23.1% |

| Eating disorder pathology | 3 | 3 | 33.3% |

| Ethnicity (white vs. others) | 1 | 1 | 100% |

| Explicit affect toward self-harm stimuli | 1 | 1 | 0% |

| Explicit affect toward unpleasant stimuli | 1 | 1 | 0% |

| Exposure to peer NSSI | 3 | 3a | 100% |

| Family functioning and structure | 2 | 2 | 0% |

| Female | 8 | 7 | 100% |

| General psychopathology2 | 3 | 3 | 0% |

| Hopelessness | 3 | 3 | 0% |

| Impulsivity | 5 | 2 | 0% |

| Misc externalizing symptoms | 4 | 3a | 0% |

| Misc internalizing symptoms | 11 | 6b | 0% |

| NSSI Affect Misattribution Procedure | 1 | 1 | 0% |

| NSSI Implicit Association Test | 3 | 2 | 0% |

| Parental psychopathology | 20 | 2 | 45.0% |

| Patient prediction3 | 2 | 2 | 0% |

| Prior NSSI | 12 | 11 | 41.67% |

| Prior NSSI (aspect)4 | 6 | 2 | 33.3% |

| Prior suicidal thought/behavior | 12 | 6 | 75.0% |

| PTSD diagnosis | 2 | 2 | 100% |

| Religion | 1 | 1 | 100% |

| Social factors | 9 | 6c | 0% |

| Substance abuse symptoms | 3 | 3 | 100% |

| Treatment history | 1 | 1 | 0% |

| Unpleasant Affect Misattribution Procedure | 1 | 1 | 0% |

2 studies, 3 unique samples.

5 studies, 6 unique samples.

4 studies, 6 unique samples.

Older versus younger.

General psychopathology includes the following: scores on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and the General Health Questionnaire.

Patient prediction is a 0–4 scale assessing self-reported likelihood of engaging in future NSSI (item from the SITBI).

NSSI Aspect refers to different aspects of NSSI engagement, including recency, number of methods used, reported reason for engaging in NSSI.

2.3. Statistical analysis

We performed the meta-analysis using Comprehensive Meta-analysis Version 3.0 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, n.d.) software. We used random-effects models for the present analysis because, unlike fixed effects models, these models allow for true effects to differ across different scenarios (e.g., study samples, methods, follow-up lengths). Accordingly, random-effects models estimate both within- and between-study variance, providing an estimate for a distribution of effects. Given the diverse methods, designs, and samples across the 20 published reports, we hypothesized that there would be large between-study variance.

Odds ratios were the primary metric of the present meta-analysis. Prediction cases were reported in terms of odds ratios (n = 52) or they were converted into odds ratios from available statistics (i.e., t-tests, Cohen's d, means and standard deviations, risk ratios, chi-squared analyses, or 2 × 2 tables with rates and raw information) using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis program (n = 122). Unfortunately, it was not possible to convert betas from regression, hazard ratios, or most advanced statistical techniques into odds ratios using our current software; therefore, reports including only those types of statistics were excluded (n = 14). When possible, we opted to use zero-order (i.e., unadjusted) effects for each prediction case to provide the purest estimation of their effects. This was possible for the vast majority of prediction cases (92%), with 18 of the 20 reports providing unadjusted effects.

2.4. Analytic strategy

We began by calculating descriptive statistics for each of the included published reports. Next, we calculated the overall weighted effect size across the studies; in other words, we combined all prediction cases across risk factor categories into a single overall category and tested its ability to predict NSSI. We then divided prediction cases into specific risk factors categories and calculated their weighted effect sizes. These analyses included overall estimates, confidence intervals, z-values, and I-squared (I2) values. I2 is an index of study heterogeneity, providing a percentage of the proportion of variance in the meta-analysis due to between study variance. I2 values from 0–25% indicate low heterogeneity, 26–50% indicates medium heterogeneity, and 51– 100% indicates high heterogeneity (Higgins, Thompson, Deeks, & Altman, 2003). We note here again that random-effects models account for this heterogeneity when estimating weighted effect sizes. Finally, we examined the impact of our proposed moderators (i.e., sample age, population, and NSSI measurement) on this variability, estimating effect sizes for each moderator level. Next, we employed a random effects meta-regression to analyze the associations between standardized odds ratios (the dependent variable) and each of these moderators (the independent variables) to determine the unique role of each of these factors. Meta-regression includes standardized effect sizes as the dependent variable and weights each prediction case for the independent variables differently. Specifically, we employed a random effects form of this technique called unrestricted maximum likelihood meta-regression.

Because significant findings – especially the large significant findings that are disproportionately detected by small studies – are more likely to be published, we also calculated the following publication bias statistics: Orwin's fail-safe N, Egger's test of the intercept, and Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis. Orwin's fail-safe N indicates whether the overall effect is a robust, non-zero effect. Egger's regression test reveals a common bias wherein smaller and less precise studies produce the largest effects, biasing the results. Finally, Duval and Tweedie's Trim and Fill test estimates the number of missing studies due to publication bias and then imputes what the effect size would be if those studies had been published. Given that publication bias statistics require at least three prediction cases, we could not conduct publication bias statistics on each individual category.

3. Results

3.1. Question 1: what are the basic characteristics of this literature?

3.1.1. Number of published reports across time

A total of 20 published reports and 16 unique study samples were included in the present meta-analysis. The earliest published report was *Van der Kolk, Christopher, and Perry (1991); the next qualifying study was not published until 17 years later (*Zanarini et al., 2008).

3.1.2. Prediction cases and trends across time

These 20 published reports produced a total of 247 prediction cases. Of these, we excluded 79 cases. Sixty-six of these prediction cases were excluded because they were used across multiple time points within one study and 13 prediction cases were excluded because they were hypothesized to reduce NSSI (i.e., protective factors). In total, 168 risk factor prediction cases were included in the present analysis. Only 3.57% of these prediction cases were published before 2008.

Each of the 168 prediction cases was sorted into one of 34 risk factor categories (see Table 3). Risk factor categories included both binary and continuous prediction cases (e.g., diagnosis of depression and depressive symptoms, respectively). On average, there were seven prediction cases per study; 56 prediction cases were coded as “binary” and 112 were coded as “continuous” (see Table 3 for the percentage of binary prediction cases within each category). These risk factor categories were drawn from an average of 4.6 cases from 3.1 unique samples.

3.1.3. Sample characteristics

Across these published reports, there were 5078 unique participants ranging in age from 10–44 years. Three of the 16 unique samples did not provide a mean age for participants and four did not provide a standard deviation. Using available statistics, the average age of participants was 21.32 (SD = 4.41). Seven of the 16 unique samples were adult, eight adolescent, and two were mixed (i.e., *Tuisku et al., 2014; *Cox et al., 2012). Because only two studies employed a mixed adolescent and adult sample, and those samples comprised primarily of adolescents, the two mixed-age studies were coded as adolescent. This resulted in 53 adult and 115 adolescent prediction cases (see Table 1). Six studies (nine published reports) included general samples; eight samples (nine published reports) included clinical samples; and the remaining two studies included samples with a history of NSSI. In total, 52 prediction cases were drawn from general samples, 87 from clinical, and 29 from NSSI history samples.

Table 1.

Included study information.

| Study name | Population size at follow-up | NSSI participants | Sample type | Population | Sample ages (range, mean, SD) | NSSI binary or continuous | Length of study (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *Andrews, Martin, Hasking, and Page (2013) | 1937 Australian students | 57a | General | Adolescent | 12–17 years, Mean (SD) = 14.9 (0.96) | Binary | 12 |

| *Anestis et al. (2012) | 127 people meeting BN criteria | Unclear | High risk | Adult | 18–55 years, Mean (SD) = 25.34 (7.71) | Continuous | 0.46 |

| *Cox et al. (2012) | 352 offspring of parents with mood disorders | 26 | High risk | Adolescent and adult | 10 + years, Mean (SD) = 17.9 (6.9) | Binary | 12–96, Mean (SD) = 45.6 (21.6) |

| *Franklin et al. (2014) | 49 adults with self-cutting history | 24 | History of NSSI | Adult | Mean (SD) = 24 (8.28) | Continuous | 6 |

| Glenn and Klonsky (2011) | 51 adults with NSSI history | 32 | History of NSSI | Adult | Mean (SD) = 18.96 (1.57) | Continuous | 12 |

| *Guerry and Prinstein (2009) | 102 inpatient adolescents | 24 females, 5 males | High risk | Adolescent | 12–15 years, Mean (SD) = 13.51 (0.75) | Continuous | 18 |

| *Hankin and Abela (2011) | 97 community adolescents | 18 | General | Adolescent | 11–14 years, Mean (SD) = 12.63 (1.25) | Binary | 30 |

| *Lundh et al. (2013) | 452 middle-school girls, 434 middle-school boys | 26 females, 21 males | General | Adolescent | 13–15 years (no mean provided) | Continuous | 12 |

| *Lundh, Wångby-Lundh, and Bjärehed (2011) | 452 middle-school girls, 434 middle-school boys | 26 females, 21 males | General | Adolescent | 13–15 years (no mean provided) | Binary | 12 |

| *Marshall et al. (2013) | 506 Swedish middle-school students | Unclear | General | Adolescent | 12–14 years, Mean (SD) = 13.21 (0.57) | Continuous | 24 |

| *Martin, Thomas, Andrews, Hasking, and Scott (2014) | 1975 Australian students | 58a | General | Adolescent | 12–17 years, Mean (SD) = 14.87 (0.95) | Binary | 12 |

| *Prinstein et al. (2010)–Study 1 | 377 middle-school adolescents | Unclear | General | Adolescent | 6-8th grade (no mean provided) | Continuous | 12 |

| *Prinstein et al. (2010)–Study 2 | 102 psychiatric inpatient adolescents | 24 females, 5 males | High risk | Adolescent | 12–15 years, Mean (SD) = 13.51 (0.81) | Continuous | 18 |

| *Roaldset, Linaker, and Bjørkly (2012) | 307 psychiatric inpatients in Norway | 10 | High risk | Adult | Mean = 44 (no range provided) | Binary | 12 |

| *Selby, Franklin, Carson-Wong, & Rizvi, 2013 | 47 individuals high in dysregulated behaviors | 7 | High risk | Adult | Mean (SD) = 35 (15.87) | Continuous | 0.46 |

| Tatnell, Kelada, Hasking, and Martin (2013) | 1973 Australian students | 75a | General | Adolescent | 12–18 years, Mean (SD) = 13.89 (0.97) | Binary | 12 |

| *Tuisku et al., 2014 | 137 Finnish depressed adolescents | 22 | High risk | Adolescent and adult | 13–19 years, Mean (SD) = 16.5 (1.59) | Binary | 96 |

| *Van der Kolk, Christopher, and Perry (1991) | 74 personality and mood disorder patients | 9 | General | Adult | 18–39 years | Continuous | 24–108, Mean = 48 |

| *Wilkinson et al. (2011) | 163 depressed adolescents | 57 | High risk | Adolescent | 11–17 years, Mean (SD) = 14.2 (1.2) | Binary | 6.44 |

| *Zanarini et al. (2008) | 262 personality disorder patients | 40 | High risk | Adult | 18–35 years, Mean (SD) = 27 (6.3) | Binary | 24 |

| Total unique participants: | 5078 |

236 total participants engaged in NSSI at T2; however, only new, or “incident” cases, were included in analyses

3.1.4. Follow-up lengths

Study follow-up lengths ranged from .45 to 108 months, with a mean follow-up length of 20.65 months (median = 12 months).

3.1.5. NSSI Measurement

A total of 15 different measures of NSSI were used in these reports (see Table 2). These measures assessed NSSI using specific types of behaviors (e.g., self-cutting; n = 2), large checklists of potential behaviors (n = 14), or open-ended questions assessing NSSI engagement without specifying behaviors (n = 5). Of those assessing NSSI with open-ended questions, slightly different definitions of NSSI were employed in the questions (see Table 2). Half of the included studies used a binary NSSI variable (yes versus no NSSI engagement over the follow-up) and the other half used continuous or ordinal scales to quantify NSSI engagement. In total, 102 prediction cases were coded as predicting a “binary” NSSI outcome and 66 as predicting a “continuous” NSSI outcome.

Table 2.

NSSI measures.

| NSSI measure | Question to assess for NSSI | Question format | Interview v. self-report | Studies using that measure | Notable features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA; Posner et al., 2007) | “Have you ever done anything to harm yourself without ANY intention of killing yourself (like to relieve stress, feel better, get sympathy, or get something to happen)?” | Open-ended | Interview | *Cox et al. (2012) | a. Definition of NSSI states that the goal of the behaviors is to effect changes in others or the environment or to relieve distress. b. Specific behaviors unspecified. |

| 2. Deliberate Self Harm Inventory, 9 item version (DSHI-9r; Bjärehed & Lundh, 2008; Gratz, 2001). | “Have you ever intentionally (i.e., on purpose)___ your body (without intending to kill yourself)?” | Checklist | Self-report | *Lundh et al. (2013); *Lundh et al. (2011); *Marshall et al. (2013) | a. Includes preventing wounds from healing. |

| 3. Functional Assessment of Self-Mutilation (FASM; Lloyd, Kelley, & Hope, 1997) | “In the past year, have you engaged in the following behaviors to deliberately harm yourself” (rule out if did so with suicidal intent) | Checklist | Self-report | *Hankin and Abela (2011) | a. Includes picking at wound and unidentified “other.” b. Required 2 + engagements. |

| 4. Inventory Statements About Self Injury | Behaviors performed “intentionally (i.e., on purpose) and without suicidal intent.” | Checklist | Self-report | Glenn and Klonsky (2011) | a. Includes interfering with wound healing, pinching, pulling hair, rubbing skin against rough surfaces. b. Includes swallowing dangerous chemicals (indirect self-harm). |

| 5. Lifetime Self-Destructiveness Scale (LSDS; Zanarini et al., 2006) | Behaviors engaged in “with the purpose of deliberately inflicting physical damage to one's body (without suicidal intent)” | Open-ended | Interview | *Zanarini et al. (2008) | a. Includes unidentified “other.” |

| 6. Personalized NSSI variable | NSSI defined as behaviors with “the intention to injure oneself without the wish to kill oneself” | Open-ended | Interview | *Roaldset et al. (2012) | a. Specific behaviors unspecified. |

| 7. Personalized NSSI variable | “Harmed or hurt your body on purpose (for example, cutting or burning your skin, hitting yourself, or pulling out your hair) without wanting to die.” Frequency of each item was reported on a 6-point scale. | Checklist | Self-report | *Prinstein et al. (2010)–Study 1 | a. Includes pulled hair out and unidentified “other.” |

| 8. Personalized NSSI variable | “Non-suicidal self-injurious behaviors (i.e., cut/carved skin, hit self, pulled hair out, burned skin, or other) without suicide intent.” Frequency of engagement in each item was reported on a 5-point scale. | Checklist | Self-report | *Guerry and Prinstein (2009); *Prinstein et al. (2010)-Study 2 | a. Includes pulled hair out and unidentified “other.” |

| 9. Personalized NSSI variable | “Any instance where you purposely enact physical harm to your body, without any intent to die.” | Checklist | Self-report | *Selby et al., 2013 | a. Specific behaviors unspecified. |

| 10. Personalized NSSI variable | Participants reported histories of “Cutting” and/or “Other self-injurious behavior (head banging, picking, or burning)” | Checklist | Self-report | *Van der Kolk, Christopher, and Perry (1991) | a. Only includes cutting, head banging, picking, burning. |

| 11. Personalized NSSI variable | Summed the total number of times each participant endorsed any of the following behaviors: cutting, burning, repeated hitting, and head banging. | Checklist | Self-report | *Anestis et al. (2012) | a. Only includes cutting, burning, repeated hitting, and head banging. |

| 12. Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire (SHBQ Gutierrez et al., 2001) | “Hurting yourself on purpose without trying to die”. The NSSI subscale of the SHBQ included: “Have you ever hurt yourself on purpose” | Open-ended | Interview | *Andrews et al. (2013); Tatnell et al. (2013); *Martin et al. (2014) | a. Specific behaviors unspecified. b. Tatnell et al. (2013) explicitly exclude self-poisoning and substance ingestion (indirect self-harm), *Andrews et al. (2013) and *Martin et al. (2014) do not, but unclear if included. c. Tatnell et al. (2013) include scratching. |

| 13. Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview (SITBI; Nock et al., 2007) | “Have you ever purposely hurt yourself without wanting to die?” | Checklist | Interview | *Franklin et al. (2014) | a. Includes skin picking, pulled hair out, picking at wound, and “other.” |

| 14. Suicidality and self-harm sections of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for Adolescents-Lifetime Version (Klein, 1993)/the Kiddie-Sads-Present and Lifetime Version(K-SADS-PL; Delmo et al., 2000) | “Self-mutilation, or other acts done without intent of killing himself.” Asks kids, “Did you ever try to hurt yourself? [...]” If yes, “Some kids do these types of things because they want to kill themselves, and other kids do them because it makes them feel a little better afterward. Why do you do these things?” | Open-ended | Interview | *Wilkinson et al. (2011); *Tuisku et al., 2014 | a. Specific behaviors unspecified. |

3.2. Question 2: what is the overall effect size for risk factors of NSSI and are there any especially strong risk factors?

3.2.1. Overall NSSI prediction and publication bias

Analyses produced an overall weighted mean odds ratio of 1.59 (95% CI: 1.50 to 1.69). Heterogeneity statistics suggested that the overall variance between these studies was high (I2 = 83.53). In other words, approximately 84% of the variance could be accounted for by between-study variance.

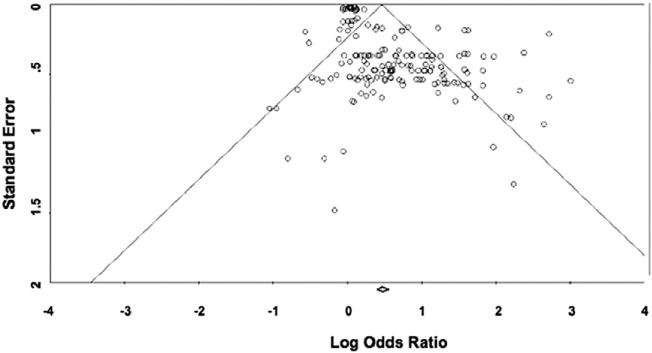

We assessed for potential publication bias in several different ways. Orwin's Fail-Safe N indicated that 1384 prediction cases with an odds ratio of 1.0 would be needed to bring the overall weighted odds ratio to 1.10 (i.e., our pre-defined trivial effect magnitude), suggesting a robust non-zero effect. However, Egger's regression test showed significant publication bias (intercept = 1.66; 95% CI: 1.31 to 2.01, t = 9.36, df = 166, p < .0001) and the funnel plot was highly asymmetrical (see Fig. 2). Moreover, Duval and Tweedie's Trim and Fill test estimated that 62 prediction cases lower than the mean were missing from analyses. Had these missing prediction cases been published and included in the meta-analysis, the weighted odds ratio would have dropped to 1.16 (95% CI: 1.10 to 1.24). These publication bias statistics show robust NSSI prediction (i.e., Orwin's Fail-Safe N), but also indicated significant publication bias that inflated the estimated magnitude of NSSI prediction (i.e., Egger's and Duval and Tweedie's tests).

Fig. 2.

Funnel plot with 95% confidence interval.

3.2.2. Risk factor categories and NSSI

Next, we examined differences in effect size magnitude across specific risk factor categories (see Table 4). Prediction was weak across all categories. Categories drawn from only one sample (n = 9) were not examined directly. Importantly, risk factor category estimates drawn from only two unique samples (n = 9) were included. However, estimates drawn from so few cases and samples are potentially unstable and extreme approximations. Therefore, although these risk factor categories are included in the table to highlight areas for future research, we limited our discussion to categories with three or more prediction cases from three or more unique samples, as these represent more stable and reliable estimates.

Table 4.

Risk factor magnitude across categories.

| Risk factor categories | Weighted odds ratio | Lower limit | Upper limit | z-Value | # unique samples | # cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior NSSI | 5.95**a | 3.57 | 9.93 | 6.84 | 11 | 12 |

| Depression | 1.98** | 1.34 | 2.94 | 3.39 | 10 | 13 |

| Female | 1.80** | 1.21 | 2.67 | 2.92 | 7 | 7 |

| Prior suicidal thought/behavior | 2.21** | 1.42 | 3.44 | 3.49 | 6 | 12 |

| Social factors | 1.05 | 0.94 | 1.18 | 0.90 | 6a | 9 |

| Misc internalizing symptoms | 1.37** | 1.20 | 1.57 | 4.55 | 6b | 11 |

| Age1 | 1.19 | 0.75 | 1.87 | 0.74 | 6 | 7 |

| Affect dysregulation | 1.05* | 1.01 | 1.08 | 2.80 | 6 | 7 |

| Anxiety | 1.19 | 0.98 | 1.44 | 1.80 | 5 | 6 |

| Hopelessness | 3.08** | 1.88 | 5.06 | 4.44 | 3 | 3 |

| Exposure to peer NSSI | 2.13** | 1.55 | 2.95 | 4.61 | 3c | 3 |

| Misc externalizing symptoms | 1.68** | 1.22 | 2.31 | 3.19 | 3c | 4 |

| General psychopathology2 | 1.17* | 1.00 | 1.35 | 2.02 | 3 | 3 |

| Substance abuse symptoms | 1.06 | 1.00 | 1.12 | 1.82 | 3 | 3 |

| Cluster b | 5.93** | 2.37 | 14.83 | 3.81 | 3 | 3 |

| ADHD | 1.11 | 0.94 | 1.30 | 1.22 | 3c | 3 |

| Eating disorder pathology | 1.81* | 1.05 | 3.11 | 2.15 | 3 | 3 |

| Patient prediction3 | 2.89** | 1.34 | 6.22 | 2.71 | 2 | 2 |

| Abuse | 2.87** | 1.69 | 4.88 | 3.89 | 2 | 4 |

| Prior NSSI (aspect)4 | 2.64** | 1.45 | 4.78 | 3.19 | 2 | 6 |

| Impulsivity | 1.63* | 1.07 | 2.49 | 2.27 | 2 | 5 |

| Parental psychopathology | 1.35** | 1.13 | 1.63 | 3.22 | 2 | 20 |

| Family functioning and structure | 1.14** | 1.06 | 1.22 | 3.69 | 2 | 2 |

| PTSD diagnosis | 1.31 | 0.58 | 2.97 | 0.65 | 2 | 2 |

| NSSI Implicit Association Test | 1.02 | 0.56 | 1.85 | 0.06 | 2 | 3 |

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

4 studies, 6 unique samples.

5 studies, 6 unique samples.

2 studies, 3 unique samples.

Older versus younger.

General psychopathology includes the following: scores on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and the General Health Questionnaire.

Patient prediction is a 0–4 scale assessing self-reported likelihood of engaging in future NSSI (item from the SITBI).

NSSI Aspect refers to different aspects of NSSI engagement, including recency, number of methods used, reported reason for engaging in NSSI.

Among categories drawn from at least three prediction cases, significant odds ratios ranged from 1.05 (95% CI: 1.00–1.05; affect dysregulation) to 5.95 (95% CI: 3.57–9.93; history of NSSI engagement). In order of magnitude: prior NSSI, cluster b, hopelessness, prior suicidal thoughts and behaviors, exposure to peer NSSI, depression diagnosis, depressive symptoms, eating disorder pathology, being female, externalizing psychopathology, internalizing psychopathology, general psychopathology, and affect regulation each emerged as significant predictors of NSSI.

3.3. Question 3: which factors moderate the associations between risk factors and NSSI?

3.3.1. NSSI measure type

Cases predicting continuous outcomes of NSSI engagement (n = 66) generated a significantly stronger weighted mean odds ratio (OR = 2.37; 95% CI: 1.99–2.83) than cases predicting binary NSSI engagement (n = 102; OR = 1.23; 95% CI: 1.17–1.30).

3.3.2. Sample population

Weighted mean odds ratios drawn from general samples were slightly weaker (n = 52, OR = 1.47; 95% CI: 1.37 to 1.58, p < .001) than those drawn from clinical (n = 87, OR = 1.75, 95% CI: 1.57 to 1.94, p < .001) and NSSI history samples (n = 29, OR = 2.05; 95% CI: 1.57 to 2.69, p < .001).

3.3.3. Sample age

NSSI prediction cases drawn from adolescent samples generated significantly weaker effects (n = 115; OR = 1.46; 95% CI: 1.38 to 1.56, p < .0001) than those drawn from adult samples (n = 53; OR = 2.11; 95% CI: 1.80 to 2.48, p < .001).

3.3.4. Prediction case measure type

Binary prediction cases (i.e., cases drawn from variables with a scale ranging from 0 to 1) resulted in a significantly stronger weighted mean odds ratio (n = 56; OR = 2.17; 95% CI: 1.74–2.70) than continuous prediction cases (n = 112; OR = 1.38; 95% CI: 1.30–1.46).

3.3.5. Random effects meta-regression

Meta-regression including each moderator indicated significant change in predictive ability across moderator levels (Q = 1013.79, df = 167, R2 = 0.52, p < .001). However, only NSSI measure type (i.e., continuous versus binary) and prediction case measurement type (i.e., continuous versus binary), but not sample age or sample population, significantly impacted odds ratio magnitudes (b = −0.66, p < .01). Specifically, odds ratio magnitudes were larger when continuous measures of NSSI and binary prediction cases were used.

4. Discussion

Each year, millions of people purposely hurt themselves without wanting to die (Klonsky, 2011; Nock & Prinstein, 2004). Historically, the majority of research on NSSI has been cross-sectional; however, prospective risk factor research is growing. Risk factor research is critical for advancing the conceptualization, prediction, and treatment of NSSI. The primary goal of the present meta-analysis was to synthesize the NSSI risk factor literature. Results highlighted several statistically significant NSSI risk factors, but overall effects were weaker than anticipated and most significant risk factors did not result in large increases in the absolute odds of future NSSI.

We first examined the characteristics of the NSSI risk factor literature. All but one of the 20 included studies were conducted after 2008 (*Van der Kolk, Christopher, and Perry, 1991). Study participants were nearly evenly divided between adults (primarily young adults) and adolescents. Only two studies included samples where all participants had a history of NSSI (*Franklin, Puzia, Lee, & Prinstein, 2014; Glenn & Klonsky, 2011), and both of these studies involved adult samples. Adolescent sample studies typically included more prediction cases, resulting in a majority of prediction cases examined being drawn from adolescent samples. Few studies examined short-term risk factors for NSSI, as the average follow-up length was longer than one year.

Analyses revealed that overall risk factor strength was surprisingly weak, especially when considering clinical utility. The overall weighted mean odds ratio was 1.56 and this dropped to 1.16 when adjusting for publication bias. These findings suggest weak overall prediction of future NSSI. In terms of absolute odds, among adults such an effect would raise the one-year likelihood of an adult engaging in NSSI from approximately one to 1.4 in every 100 adults (i.e., increase in absolute odds from .009 to .014). This estimate would be higher in adolescent and clinical samples, but still low in an absolute sense. Moreover, clinicians are most often asked to assess short-term risk (i.e., weeks, days, or hours) rather than risk over many months or years. The present findings suggest that current risk factor magnitudes may be too small to be informative over these shorter time periods.

We also examined the magnitude of specific risk factor categories. Among categories including at least 3 prediction cases, a history of NSSI (drawn from 11 unique samples) and cluster b personality (drawn from 3 unique samples) were the strongest predictors, with odds ratios just below 6.0. Notably, however, cluster b personality had a very large confidence interval compared to other risk factor categories. This finding should be considered with caution, as two out of three studies examining this factor were non-significant, and each of the studies had very large confidence intervals around this effect. Outside of these two factors, risk factor strength was relatively weak. Hopelessness was the next strongest risk factor, with an odds ratio around 3.0; remaining factors clustered around an odds ratio of 2.0. Importantly, we found significant publication bias across this literature, suggesting that the present results are likely inflated estimates of true risk factor magnitudes. In fact, many of the categories that appeared significant according to the present meta-analysis may not be significant when accounting for publication bias as many of these effects were close to 1.0.

Given that risk factor magnitude may change across different conditions, we examined whether four factors moderated overall risk factor magnitude: NSSI measurement type, severity of sample, age of sample, and prediction case measurement type. Results revealed that each of these factors generated small but statistically significant moderation effects. Specifically, continuous NSSI measurement produced significantly stronger NSSI prediction than binary measurement; clinical and NSSI samples produced significantly stronger NSSI prediction than community samples; adult samples produced significantly stronger prediction of NSSI than adolescent samples; and binary prediction cases produced significantly stronger NSSI prediction than continuous cases.

Follow-up analysis (i.e., meta-regression) assessing the unique impact of each of these factors indicated that NSSI measurement type and prediction case measurement type, but not sample population or age, were significant moderators. This finding has important implications both for the interpretation of the present meta-analysis and future research on NSSI risk factors. Regarding interpretation of the present meta-analysis, these findings highlight that differences in odds ratio magnitudes are difficult to interpret without considering the scale used for prediction cases. Risk factor categories drawn from primarily continuous prediction cases will likely have lower odds ratio magnitudes than risk factor categories drawn from primarily binary prediction cases (see Table 3 for the percentage of binary prediction cases within each category). Importantly, this does not indicate that binary measures are “better” NSSI predictors, as this difference simply represents a mathematical artifact. Specifically, a low but significant odds ratio resulting from a continuous measure with a wide score range (e.g., 0–40) could indicate greater risk than a larger odds ratio drawn from a binary scale, as odds ratios reflect increased odds for each unit change on a given measure. Regarding future research on NSSI risk factors, these findings indicate that continuous NSSI measurement results in stronger overall prediction. In fact, weaker prediction among adolescent samples may relate to the higher percentage of these studies using binary NSSI measurement (i.e., 62% of studies using adolescent samples versus only 37.5% of studies using adult samples).

Interestingly, two of the strongest NSSI risk factors, NSSI history and hopelessness, are also significant risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that a prior history of NSSI is the strongest identified risk factors for future suicide attempts (OR = 4.03) and hopelessness is one of the strongest predictors for both suicide ideation and suicide death, though odds ratios remain relatively low (i.e., 2.19 and 1.94 respectively; Franklin et al., 2015). Moreover, we found that prior history of suicidal thoughts and behaviors is a risk factor for NSSI, which parallels findings that those thoughts and behaviors are also risk factors for suicide ideation, attempts, and death (Franklin et al., 2015). These findings suggest that certain factors may act as risk factors for both suicidal and nonsuicidal thoughts and behaviors. This is especially important given the high overlap between these thoughts and behaviors (e.g., Lloyd-Richardson et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2011; Brunner et al., 2007; MacLaren & Best, 2010). Future research disentangling whether this overlap occurs simply because NSSI is predictive of future suicidal behaviors (e.g., does hopelessness predict suicidal thoughts and behaviors when controlling for a history of NSSI?) or whether these factors are independently important for both types of behaviors could be especially important in understanding this association.

Although cross-sectional research has indicated that certain factors, such as internalizing symptoms and emotion dysregulation, are strong NSSI correlates (e.g., Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Glenn & Klonsky, 2011), the present meta-analysis suggests that these factors are not particularly strong risk factors. These factors may highlight important functions of NSSI engagement, but the present findings indicate that these correlates are not necessarily strong risk factors on their own. However, prior to drawing strong conclusions from these findings, it is important to consider that included studies utilized relatively long follow-up periods (i.e., approximately 12 months). It is possible that these factors are stronger NSSI risk factors when examined over shorter follow-up periods and when examined in conjunction with several other potential risk factors.

4.1.1. Limitations and future directions

The present review identified four key areas that represented both limitations of the present meta-analysis and future directions for research on NSSI risk factors. First, measures of NSSI varied considerably across the 20 included studies. These measures included varying coding strategies (i.e., binary, continuous), types of behaviors, and types of questions to assess NSSI (e.g., open-ended, checklist). In terms of NSSI coding, half of the included longitudinal studies assessed NSSI with binary measures. Binary measures impede a fine-grained understanding of changes in NSSI. Moreover, all but one of the studies using binary NSSI measurement allowed for individuals who self-harmed one time to be placed in the “NSSI group.” It remains unclear the exact number of episodes needed to represent pathological self-harm; however, emerging evidence demonstrates differences in pathology and risk of future self-harming behaviors among those who engage in infrequent and frequent NSSI (e.g., Hamza & Willoughby, 2013; Klonsky & Olino, 2008; Whitlock, Muehlenkamp, & Eckenrode, 2008). Binary coding, therefore, may lead to misclassification and an artificial inflation of the number of people in the self-harming group. Continuous measures, in contrast, help differentiate frequent and infrequent NSSI engagement and can highlight factors that both increase and decrease NSSI. Using continuous measures of NSSI in future research may be better suited for identifying meaningful risk factors for these behaviors.

Regarding the different types of behaviors included, these measures diverged in their inclusion of minor behaviors (e.g., scab picking), indirect self-harm (e.g., self-poisoning), and socially sanctioned behaviors (e.g., self-tattooing, self-piercing). Emerging research suggests that there may be important differences across these behaviors. For example, moderate NSSI (e.g., cutting) is associated with greater history of psychopathology, more frequent hospitalizations, and increased suicidal thoughts and behaviors compared to mild NSSI (e.g., picking at wounds; Lloyd-Richardson et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2011). Moreover, some of the behaviors included in these checklists may be better accounted for by other processes, such as hair pulling (trichotillomania), skin picking (skin picking disorder), tattooing/piercing (socially sanctioned behaviors), self-poisoning (indirect self-harm), or head-banging (stereotypic self-harm associated with developmental disorders). Given growing evidence of differences across these different types of behaviors, future research investigating moderate versus minor and direct versus indirect NSSI may provide important insights for the field. In sum, use of different types of questions to assess NSSI may lead to different interpretations and responses across participants. Risk factor research requires that the outcome of interest be defined clearly, validly, and reliably (Kraemer et al., 1997). Accordingly, each of these measurement discrepancies may limit the ability to precisely identify risk factors.

Second, future research should consider including samples where all members have a history of NSSI. There were only two such studies in the present meta-analysis. A history of NSSI increases the likelihood of future NSSI engagement (e.g., *Cox et al., 2012; *Franklin et al., 2014; Glenn & Klonsky, 2011; *Guerry & Prinstein, 2009; *Lundh, Bjärehed, & Wångby-Lundh, 2013; *Marshall, Tilton-Weaver, & Stattin, 2013). As such, research using these samples will likely result in greater NSSI engagement over the follow-up period, increasing statistical power to identify risk factors. Increased power would likely provide much more reliable and accurate estimates of effect magnitude, both within and across studies. Moreover, results from these studies may more precisely isolate factors uniquely related to NSSI engagement, especially when controlling for prior NSSI frequency. Importantly, risk factors for continued NSSI and the onset of NSSI may differ. NSSI onset risk factors could be especially important for identification of people at risk for engaging in NSSI and thereby may target groups for prevention. Very few studies have sought to specifically examine risk factors for NSSI onset (n = 2), and these studies were conducted in general samples, typically carrying more ambiguity about risk factor specificity. Future research should consider using large clinical samples without a history of NSSI. Such studies would likely have greater power than general samples and would provide more insight into factors that relate more uniquely to someone starting to engage in NSSI rather than factors that contribute to the continuation of these behaviors.

Once such NSSI risk factors are identified, future research could consider studying samples at high risk for NSSI to better determine risk factors for NSSI onset. Such studies would likely have higher power than general samples and would provide more insight into factors that relate more uniquely to someone starting to engage in NSSI rather than factors that contribute to the continuation of these behaviors.

Third, more longitudinal studies of NSSI risk factors are needed. Only 20 risk factor studies qualified for the present-meta analysis. Consequently, risk factor categories were often limited to few prediction cases (averaging around four) and were drawn from even fewer unique samples (averaging around three). Accordingly, it is unclear whether observed estimates accurately reflect risk factor strength across these different categories. More NSSI risk factor research is needed to better estimate risk factor magnitudes.

Fourth, study follow-up lengths averaged around 12 months. Although no factors emerged as especially strong risk factors across these long follow-up periods, it is unclear whether prediction would be stronger over shorter follow-up periods. Certain risk factors, especially variable risk factors (e.g., state-based risk factors that change over time), could be stronger over shorter follow-up intervals. For example, although emotion dysregulation may not be a strong predictor of NSSI one year later, it could emerge as a stronger NSSI risk factor when examined over a shorter interval (e.g., over the following month). Studies examining this factor over longer-term periods may not be suited to capture this relationship. The present meta-analysis did not have sufficient prediction cases to test whether risk factor categories were stronger over different follow-up intervals, but future research examining NSSI risk factors over shorter follow-up periods could provide important insights into this possibility.

Notably, the present meta-analysis analyzed risk factors in isolation. Across the 20 included reports there was minimal examination of interactions, and these interactions were too idiosyncratic to use in the present meta-analysis. Combinations of certain NSSI risk factors could increase their combined magnitude, and may improve predictive power. Future research should consider examining which factors combine, and in what ways they combine (e.g., additive, interaction), to substantially improve prediction beyond single risk factors. Large-scale studies examining multifaceted interactions could prove particularly useful in prediction of these complex behaviors.

5. Conclusions

The present meta-analysis synthesized data from nearly a decade of research examining NSSI risk factors. Results suggested significant, but weak, NSSI prediction and highlighted variables that might represent risk factors for NSSI. More importantly, however, these results emphasized that we currently lack strong risk factors for NSSI. Additionally, the present meta-analysis highlighted extreme heterogeneity across NSSI measurement, limiting our ability to accurately identify NSSI risk factors. Future research on NSSI should seek to standardize NSSI measurement and to conduct longitudinal studies exploring both traditional and novel risk factors for these behaviors, especially among participants with a history of NSSI. Such research would foster advances in understanding, predicting, and treating NSSI.

HIGHLIGHTS.

We conducted a weighted random-effect meta-analysis of NSSI risk factor studies.

Results suggested significant, but weak, NSSI risk factor magnitude.

A prior history of NSSI was the strongest risk factor (odds ratio around 6).

Remaining risk factor magnitudes were low, suggesting limited clinical utility.

Continuous NSSI measurement resulted in stronger NSSI risk factor magnitude.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Ribeiro was supported in part by a training grant (T32MH18921) from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Role of funding sources

This work was supported in part by funding from the Military Suicide Research Consortium (MSRC), an effort supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs (Award No. W81XWH-10-2-0181). Opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the MSRC or the Department of Defense.

Footnotes

Contributors

KRF and JCF designed the study, conducted literature searches, and provided summaries of previous research studies. All authors assisted in coding included studies for this meta-analysis. KRF conducted the statistical analysis. KRF wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- *.Andrews T, Martin G, Hasking P, Page A. Predictors of onset for non-suicidal self-injury within a school-based sample of adolescents. Prevention Science. 2013;15(6):850–859. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0412-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Anestis MD, Silva C, Lavender JM, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Engel SG, Joiner TE. Predicting nonsuicidal self-injury episodes over a discrete period of time in a sample of women diagnosed with bulimia nervosa: An analysis of self-reported trait and ecological momentary assessment based affective lability and previous suicide attempts. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2012;45(6):808–811. doi: 10.1002/eat.20947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Roaldset JO, Linaker OM, Bjørkly S. Predictive validity of the MINI suicidal scale for self-harm in acute psychiatry: A prospective study of the first year after discharge. Archives of Suicide Research. 2012;16(4):287–302. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2013.722052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Tuisku V, Kiviruusu O, Pelkonen M, Karlsson L, Strandholm T, Marttunen M. Depressed adolescents as young adults—Predictors of suicide attempt and non-suicidal self-injury during an 8-year follow-up. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;152:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.van der Kolk BA, Christopher J, Perry MD. Childhood origins of self-destructive behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;1(48):1–2. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.12.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor SE, Klonsky ED. Daily emotion in non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2014;70(4):364–375. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Fitzmaurice G, Weinberg I, Gunderson JG. The 10-year course of physically self-destructive acts reported by borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2008;117(3):177–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Porta G, Spirito A, Emslie G, Clarke G, Wagner KD, Brent DA. Suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents: findings from the TORDIA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(8):772–781. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjärehed J, Lundh LG. Deliberate Self-Harm in 14-Year-Old Adolescents: How Frequent Is It, and How Is It Associated with Psychopathology, Relationship Variables, and Styles of Emotional Regulation? Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2008;37(1):26–37. doi: 10.1080/16506070701778951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brausch AM, Girresch SK. A review of empirical treatment studies for adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2012;26(1):3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bresin K. Five indices of emotion regulation in participants with a history of nonsuicidal self-injury: A daily diary study. Behavior Therapy. 2014;45(1):56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresin K, Gordon KH. Changes in negative affect following pain (vs. nonpainful) stimulation in individuals with and without a history of nonsuicidal self-injury. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2013;4(1):62–66. doi: 10.1037/a0025736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MZ, Comtois KA, Linehan MM. Reasons for suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in women with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(1):198. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Bryan AO, Ray-Sannerud BN, Etienne N, Morrow CE. Suicide attempts before joining the military increase risk for suicide attempts and severity of suicidal ideation among military personnel and veterans. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2014;55(3):534–541. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner R, Parzer P, Haffner J, Steen R, Roos J, Klett M, Resch F. Prevalence and psychological correlates of occasional and repetitive deliberate self-harm in adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161(7):641–649. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AL, Gratz KL, Brown MZ. Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: The experiential avoidance model. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44(3):371–394. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Cox LJ, Stanley BH, Melhem NM, Oquendo MA, Birmaher B, Burke A, Brent DA. A longitudinal study of nonsuicidal self-injury in offspring at high risk for mood disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2012;73(6):821–828. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmo C, Weiffenbach O, Gabriel M, Poustka F. Kiddie-SADS present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL). Auflage der deutschen Forschungsversion. Frankfurt am Main: Klinik für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie des Kindes-und Jugendalters der Universität Frankfurt. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Ponton LE, Hartley D. Prevalence and correlates of cutting behavior: Risk for HIV transmission. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30(5):735–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JC, Hessel ET, Aaron RV, Arthur MS, Heilbron N, Prinstein MJ. The functions of nonsuicidal self-injury: Support for cognitive-affective regulation and opponent processes from a novel psychophysiological paradigm. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119(4):850–862. doi: 10.1037/a0020896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JC, Lee KM, Puzia ME, Prinstein MJ. Recent and frequent nonsuicidal self-injury is associated with diminished implicit and explicit aversion toward self-cutting stimuli. Clinical Psychological Science. 2013;2:167, 702, 613, 503, 140. [Google Scholar]

- *.Franklin JC, Puzia ME, Lee KM, Prinstein MJ. Low implicit and explicit aversion toward self-cutting stimuli longitudinally predict nonsuicidal self-injury. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014;123(2):463–469. doi: 10.1037/a0036436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Jaroszewski AC, Nock MK. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. 2015 doi: 10.1037/bul0000084. under review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CR, Blumenthal TD, Klonsky ED, Hajcak G. Emotional reactivity in nonsuicidal self-injury: Divergence between self-report and startle measures. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2011;80(2):166–170.m. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CR, Franklin JC, Nock MK. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2015;44(1):1–29. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.945211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CR, Klonsky ED. Prospective prediction of nonsuicidal self-injury: A 1-year longitudinal study in young adults. Behavior Therapy. 2011;42(4):751–762. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein TR, Ha W, Axelson DA, Goldstein BI, Liao F, Gill MK, Birmaher B. Predictors of prospectively examined suicide attempts among youth with bipolar disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(11):1113–1122. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollust SE, Eisenberg D, Golberstein E. Prevalence and correlates of self-injury among university students. Journal of American College Health. 2008;56(5):491–498. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.5.491-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales AH, Bergstrom L. Adolescent non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) interventions. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2013;26(2):124–130. doi: 10.1111/jcap.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL. Measurement of deliberate self-harm: Preliminary data on the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2001;23(4):253–263. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Guan K, Fox KR, Prinstein MJ. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a time-invariant predictor of adolescent suicide ideation and attempts in a diverse community sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(5):842–849. doi: 10.1037/a0029429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Guerry JD, Prinstein MJ. Longitudinal prediction of adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: Examination of a cognitive vulnerability-stress model. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2009;39(1):77–89. doi: 10.1080/15374410903401195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez PM, Osman A, Barrios FX, Kopper BA. Development and initial validation of the Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2001;77(3):475–490. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7703_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamza CA, Willoughby T. Nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior: A latent class analysis among young adults. PloS One. 2013;8(3):e59955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hankin BL, Abela JR. Nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescence: Prospective rates and risk factors in a 2 1/2 year longitudinal study. Psychiatry Research. 2011;186(1):65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ [British Medical Journal] 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaess M, Hille M, Parzer P, Maser-Gluth C, Resch F, Brunner R. Alterations in the neuroendocrinological stress response to acute psychosocial stress in adolescents engaging in nonsuicidal self-injury. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(1):157–161d. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RG. Lifetime schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for adolescents. University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Pittsburgh, PA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED. Non-suicidal self-injury in United States adults: Prevalence, sociodemographics, topography and functions. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41(9):1981–1986. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, Olino TM. Identifying clinically distinct subgroups of self-injurers among young adults: A latent class analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(1):22–27. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Kazdin AE, Offord DR, Kessler RC, Jensen PS, Kupfer DJ. Coming to terms with the terms of risk. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54(4):337–343. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160065009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd EE, Kelley ML, Hope T. Poster session presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Behavioral Medicine. New Orleans; LA: 1997. Self-mutilation in a community sample of adolescents: Descriptive characteristics and provisional prevalence rates. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Richardson EE, Perrine N, Dierker L, Kelley ML. Characteristics and functions of non-suicidal self-injury in a community sample of adolescents. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37(08):1183–1192. doi: 10.1017/S003329170700027X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Lundh LG, Bjärehed J, Wångby-Lundh M. Poor sleep as a risk factor for nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescent girls. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2013;35(1):85–92. [Google Scholar]

- *.Lundh LG, Wångby-Lundh M, Bjärehed J. Deliberate self-harm and psychological problems in young adolescents: Evidence of a bidirectional relationship in girls. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2011;52(5):476–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2011.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLaren VV, Best LA. Nonsuicidal self-injury, potentially addictive behaviors, and the Five Factor Model in undergraduates. Personality and Individual Differences. 2010;49(5):521–525. [Google Scholar]

- *.Marshall SK, Tilton-Weaver LC, Stattin H. Non-suicidal self-injury and depressive symptoms during middle adolescence: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42(8):1234–1242. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9919-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Martin G, Thomas H, Andrews T, Hasking P, Scott JG. Psychotic experiences and psychological distress predict contemporaneous and future non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts in a sample of Australian school-based adolescents. Psychological Medicine. 2014;45(2):429–437. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon MK, Cloutier PF, Aggarwal S. Affect regulation and addictive aspects of repetitive self-injury in hospitalized adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(11):1333–1341. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200211000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK. Self-injury. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:339–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]