Abstract

This paper highlights a rare case of melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy involving the anterior maxilla in a 3-month-old infant. The tumor was excised completely, and the defect was reconstructed with a bilateral buccal pad of fat. The patient has been followed for 2 years without any evidence of recurrence. We propose that for similar anterior maxillary defects in infants and children, a buccal pad of fat can be utilized as an appropriate pedicled flap for coverage after tumor resection.

Keywords: Anterior maxillary defect, buccal fat pad, maxillary reconstruction, melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy, vanillyl mandelic acid

INTRODUCTION

Melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy (MNTI) is an extremely rare benign congenital tumor usually involving the head and neck region. It predominantly affects the anterior maxilla (70%) or mandible although it has been reported in other parts of the body such as the skull, brain, genital organ, and extremities.[1] It typically arise in neonates and mostly occur within 1st year of life without any gender predilection. It grows rapidly and aggressively displacing the adjacent teeth and invades the bone thus mimicking a malignancy.[2] Early and wide excision is the accepted treatment modality to minimize recurrence and malignant transformation. Often these wide excisions leave defects communicating with the nasal or antral cavity. These defects can be closed with skin or advancement flaps from the buccal vestibule.[3] Buccal fat pad (BFP) fat has been used extensively for the closure of defects in the oral cavity. Primarily, its indication has been limited to posterior maxillary defects due to its close proximity.[4] With this case report, we propose bilateral BFP as an appropriate autogenous tissue to close anterior defects in infants and neonates. Its abundant volume, close proximity to the surgical site, and its pedicled nature makes BFP an ideal alternative to skin and local advancement flap.

CASE REPORT

A 3-month-old female infant was reported with a complaint of growth in the anterior maxillary region since 2 months that were interfering with feeding. There was bleeding from the lesion since 24 h. Orofacial examination showed protruding growth from the oral cavity because of which the child was unable to close her mouth [Figure 1a].

Figure 1.

(a and b) Clinical picture depicting growth involving the right upper vestibule, alveolar ridge, and anterior hard palate. Right nose is elevated. Tooth is embedded in the lesion

A close examination revealed a swelling in the anterior right maxillary region covering the oral opening. The growth was firm in consistency, nontender, nonpulsatile, and brown to blackish in color. The surface was ulcerative, hemorrhagic and showed displaced tooth [Figure 1b]. The computed tomography scan was performed which revealed a large radiolucent expansile lesion measuring 3.5 cm × 2.4 cm × 2.6 cm and involving the maxilla and anterior part of hard palate bulging into the oral cavity with associated bony destruction [Figure 2a-c]. Fine needle aspiration cytology was performed, and the smears revealed cellular and predominantly monotonous looking small round blue cells with dispersed chromatin and scanty cytoplasm along with few scattered larger pigments containing cells. Focally, the background showed fibrillary material while mitotic figures were frequent.[5] Urine analysis showed increased levels of vanilmandelic acid (VMA) and a high level of serum alpha-fetoprotein. A provisional diagnosis of a tumor of neural crest origin was made. The tumor was excised completely with a 5 mm negative margin all around [Figure 3]. Nasal floor, septum and anterior two-third of the alveolar ridge was involved and hence resected. After achieving hemostasis, the raw surface was covered with the help of bilateral pedicled BFP that were transposed with the help of blunt dissection from the same defect [Figure 4].

Figure 2.

(a-c) Computed tomography pictures showing a huge radiolucent expansile, solid lesion with an epicenter in the anterior maxillary region. Moderate soft tissue enhancement is present. Displaced developing teeth are present on the outer surface

Figure 3.

Excised tumor

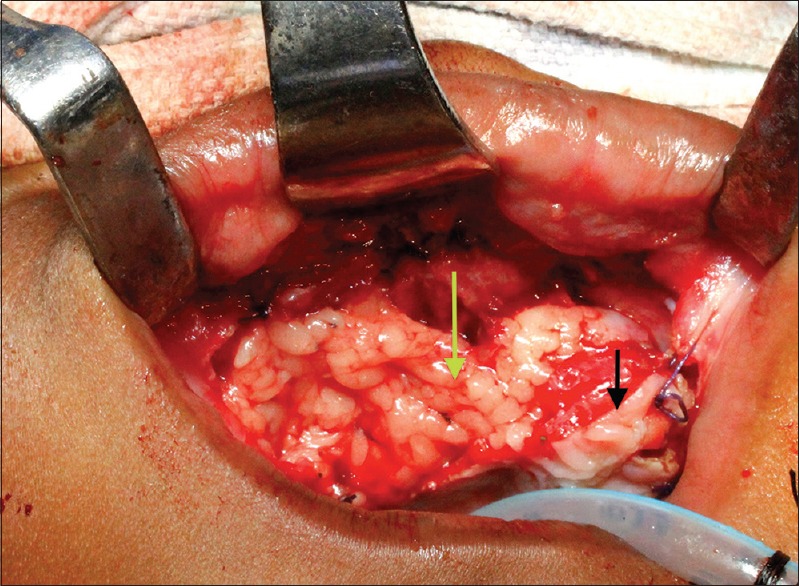

Figure 4.

Obliteration of the defect with buccal fat pad (black arrow depicts the margin of the residual palate and green arrow shows the buccal fat pad obliterating the defect completely)

Histopathologically, the sections showed a tumor arranged in nodular pattern separated by fibrous stroma. Each nodule was composed of two types of cells, the peripheral larger pigment containing cells with abundant cytoplasm and the central smaller tumor cells with small hyperchromatic nuclei and scanty cytoplasm. These smaller cells were arranged in a fibrillary background. On immunohistochemistry, the larger tumor cells were positive for Melan A while, the smaller cells were positive for CD56 indicating neuroblastic differentiation.[5] A diagnosis of MNTI was confirmed.

On 7th postoperative day, an oronasal fistula was detected on the right side. No intervention was done for it, and the patient was discharged uneventfully. Follow-up was done at regular intervals, and oronasal fistula was completely healed at the end of 6 months [Figure 5]. The child is been followed at regular intervals, and no recurrence has been noted at the end of 2 years.

Figure 5.

Sixth-month follow-up photograph showing the completely healed maxilla

DISCUSSION

BFP is an excellent tissue for intraoral reconstruction. Its local approach, pedicled nature, and minimal morbidity give it an advantage over other intraoral tissue like tongue or palate. It has been used for the closure of oroantral fistula, cleft palate defects, and buccal mucosa reconstruction in oral submucous fibrosis and similar other cases.[6,7,8] Most of these reconstructive surgical sites are in the posterior aspect of the oral cavity. It is difficult to advance the BFP to close an anterior maxillary defect. We could achieve this in this case because in infants and children, the BFP is abundant, and the anteroposterior dimension of the maxilla is small.

MNTI is rare pigmented tumor of neural crest origin. It comprises of a mixture of melanin-producing cells and primitive neural cells embedded in a fibrous stroma. Borello and Gorlin gave the present name to this tumor after reporting a high level of VMA in these patients that confirm its neuro-crestal origin.[9] An increase in VMA and serum alpha-fetoprotein is not a constant finding but depicts a tumor of neural cell origin. It is benign in nature but shows locally aggressive behavior by growing rapidly in size and invading the surrounding bone and cavities. Therefore, complete excision along with clear margins is essential to reduce the chances of recurrence that is quite frequent with inadequate excision of the tumor. An average 15–20% of recurrence rate is observed in wide excision, but it may be up to 50% among cases excised inadequately.[10] After excision, reconstruction is mandatory in infants for proper feeding, growth, and other oral functions. Split thickness skin graft and prosthesis has been used to cover the raw surfaces. In our knowledge, this is the first case of MNTI where BFP has been used for reconstruction that covers the surgical defect.

MNTI needs early diagnosis and intervention because of the aggressive and locally destructive nature. Delayed intervention leads to an extensive destruction and demands wide excision resulting in large open defects that need appropriate reconstruction. With this paper, we propose BFP as a suitable autogenous material to close anterior maxillary defects in children and infants.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Johnson RE, Scheithauer BW, Dahlin DC. Melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy. A review of seven cases. Cancer. 1983;52:661–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830815)52:4<661::aid-cncr2820520416>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mast BA, Kapadia SB, Yunis E, Bentz M. Subtotal maxillectomy for melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:1961–3. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199906000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Judd PL, Harrop K, Becker J. Melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69:723–6. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(90)90356-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stuzin JM, Wagstrom L, Kawamoto HK, Baker TJ, Wolfe SA. The anatomy and clinical applications of the buccal fat pad. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;85:29–37. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kapadia SB, Frisman DM, Hitchcock CL, Ellis GL, Popek EJ. Melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy. Clinicopathological, immunohistochemical, and flow cytometric study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:566–73. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199306000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egyedi P. Utilization of the buccal fat pad for closure of oro-antral and/or oro-nasal communications. J Maxillofac Surg. 1977;5:241–4. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(77)80117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang HM, Yan YP, Qi KM, Wang JQ, Liu ZF. Anatomical structure of the buccal fat pad and its clinical adaptations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:2509–18. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200206000-00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehrotra D, Pradhan R, Gupta S. Retrospective comparison of surgical treatment modalities in 100 patients with oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107:e1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borello ED, Gorlin RJ. Melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy – A neoplasm of neural crese origin. Report of a case associated with high urinary excretion of vanilmandelic acid. Cancer. 1966;19:196–206. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196602)19:2<196::aid-cncr2820190210>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Retna Kumari N, Sreedharan S, Balachandran D. Melanotic neuroectodermal tumour of infancy: A case report. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2007;25:148–51. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.36568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]