ABSTRACT

AprE and NprE are two major extracellular proteases in Bacillus subtilis whose expression is directly regulated by several pleiotropic transcriptional factors, including AbrB, DegU, ScoC, and SinR. In cells growing in a rich, complex medium, the aprE and nprE genes are strongly expressed only during the post-exponential growth phase; mutations in genes encoding the known regulators affect the level of post-exponential-phase gene expression but do not permit high-level expression during the exponential growth phase. Using DNA-binding assays and expression and mutational analyses, we have shown that the genes for both exoproteases are also under strong, direct, negative control by the global transcriptional regulator CodY. However, because CodY also represses scoC, little or no derepression of aprE and nprE was seen in a codY null mutant due to overexpression of scoC. Thus, CodY is also an indirect positive regulator of these genes by limiting the synthesis of a second repressor. In addition, in cells growing under conditions that activate CodY, a scoC null mutation had little effect on aprE or nprE expression; full effects of scoC or codY null mutations could be seen only in the absence of the other regulator. However, even the codY scoC double mutant did not show high levels of aprE and nprE gene expression during exponential growth phase in a rich, complex medium. Only a third mutation, in abrB, allowed such expression. Thus, three repressors can contribute to reducing exoprotease gene expression during growth in the presence of excess nutrients.

IMPORTANCE The major Bacillus subtilis exoproteases, AprE and NprE, are important metabolic enzymes whose genes are subject to complex regulation by multiple transcription factors. We show here that expression of the aprE and nprE genes is also controlled, both directly and indirectly, by CodY, a global transcriptional regulator that responds to the intracellular pools of amino acids. Direct CodY-mediated repression explains a long-standing puzzle, that is, why exoproteases are not produced when cells are growing exponentially in a medium containing abundant quantities of proteins or their degradation products. Indirect regulation of aprE and nprE through CodY-mediated repression of the scoC gene, encoding another pleiotropic repressor, serves to maintain a significant level of repression of exoprotease genes when CodY loses activity.

INTRODUCTION

Bacillus subtilis produces at least eight extracellular or cell wall-associated proteases (1, 2). The alkaline serine protease subtilisin (AprE) and the neutral metalloprotease NprE, commonly referred to as the major exoproteases, account for ∼95% of the total extracellular protease activity of B. subtilis (3). Even though the major function of AprE and NprE is thought to be supplying amino acids for growth via degradation of extracellular proteins, they have also been ascribed other physiological roles. AprE is involved in the production of two quorum-sensing signaling peptides (PhrA and CSF) (4), processing of the peptide antibiotic subtilin (5), and provision of precursors for synthesis of poly-γ-glutamate (6). Both AprE and NprE contribute to preventing autolysis of B. subtilis cells in stationary-phase cells (7).

Regulation of extracellular protease synthesis has been studied extensively because of the biotechnological importance of these enzymes and the temporal correlation between exoprotease production and the initiation of sporulation. Neither AprE nor NprE is essential for growth or sporulation of B. subtilis (3, 8), but their synthesis is directly and tightly controlled by multiple transcriptional regulators, some of which also regulate spore formation. For instance, the aprE gene is directly repressed by AbrB, ScoC, and SinR and activated by phosphorylated DegU (1, 9–20). In addition, it is indirectly regulated by other proteins, including phosphorylated Spo0A (a repressor of abrB), AbbA (an inhibitor of AbrB), phosphorylated SalA and TnrA (both of which were reported to be repressors of scoC), SinI (an inhibitor of SinR), DegS (the kinase for DegU), DegQ (an activator of DegU phosphorylation), DegR (a protector of DegU∼P), and RapG (an inhibitor of DegU∼P), as well as by factors that control the activities of the indirect regulators (such as the Spo0A phosphorelay components, the kinase for SalA, glutamine synthetase, an inhibitor of TnrA, and PhrG, an antagonist of RapG) (1, 18–25).

The nprE gene is also directly repressed by ScoC and activated by DegU∼P (1, 15–17, 19, 20); whether it responds to other regulators is not known.

Null mutations in scoC or mutations that make DegU constitutively active permit higher levels of exoprotease expression at the end of the logarithmic growth phase, but none of these mutations allow high exoprotease expression during early exponential growth in rich media (1, 20). Despite vast accumulated knowledge, the reason for this lack of expression remains unknown, suggesting the existence of additional modes of regulation.

The global transcriptional regulator CodY directly or indirectly controls the expression of more than 200 B. subtilis genes (26–28). The DNA-binding ability of CodY from B. subtilis and many other species is increased by interaction with two types of ligands: the branched-chain amino acids (isoleucine, leucine, and valine [ILV]) (29–31) and GTP (26, 31–34). As a result, CodY is active in rich media containing excess amino acids but loses activity as amino acids are exhausted (35, 36).

Global analyses of CodY-binding sites in vivo and in vitro revealed that the aprE and nprE regulatory regions contain strong binding sites (26, 27). However, DNA microarray and transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq) experiments did not detect significant changes in expression of these genes in a codY null mutant strain (26, 28). A possible explanation is that CodY regulates the expression of a second regulator of the protease genes. In fact, both aprE and nprE are directly repressed by ScoC (12, 16, 18, 23, 37, 38), a pleiotropic transcriptional regulator, which also controls expression of a minor extracellular protease (Epr), oligopeptide permeases, and other proteins (16, 39–42).

We recently reported that scoC is a direct target of CodY-mediated repression (41). As a result, the CodY-mediated regulation of some promoters, such as those of oppA and braB, which are under dual repression by CodY and ScoC, is not easily revealed by single mutations in codY or scoC (41, 42).

We hypothesized that CodY directly represses the aprE and nprE genes but that inactivation of CodY alone might not lead to higher expression because the increased synthesis of ScoC in a codY null mutant would mask the effect of inactivating CodY. In this work, we showed that CodY is indeed a strong, direct repressor of aprE and nprE and that the increased level of ScoC when CodY is inactive compensates for the loss of CodY activity or makes repression even stronger. Even in a codY scoC double mutant, however, expression of aprE in cells growing in a complex rich medium was not highly derepressed during the exponential growth phase. Simultaneous inactivation of CodY, ScoC, and AbrB did allow efficient expression of aprE and nprE at all stages of growth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture media.

The B. subtilis strains constructed and used in this study were all derivatives of strain SMY (43) and are described in Table 1 or in the text. Escherichia coli strain JM107 (44) was used for isolation of plasmids. Bacterial growth in TSS medium containing 0.5% glucose–0.2% ammonium, with supplementation with 16 amino acids (TSS+16 aa; all common amino acids except for glutamine, histidine, asparagine, and tyrosine) or without supplementation, or in DS nutrient broth medium was carried out as described previously (45).

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis strains used

| Strain | Genotype | Source or referencea |

|---|---|---|

| SMY | Prototroph | 43 |

| JH14272 | ΔamyE::[aph Φ(oppAp+-lacZ)] ΔscoC::cat trpC2 pheA1 | 39 |

| SF646 | ΔamyE::[neo Φ(hutPp+-lacZ)646] trpC2 | 79 |

| BB382 | ΔabrB::cat | 41 |

| BB383 | ΔabrB::(cat::neo) | 41 |

| BB385 | ΔscoC::cat | SMY × DNA(JH14272) |

| BB386 | ΔscoC::(cat::neo) | BB385 × pCm::Nm (80) |

| BB1043 | codY::(erm::spc) | 81 |

| BB2511 | ΔamyE::spc lacA::tet | 47 |

| GB1001 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(aprE640p+-lacZ)] lacA::tet | BB2511 × pGB1 |

| GB1002 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(nprE396p+-lacZ)] lacA::tet | BB2511 × pGB2 |

| GB1005 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(aprE640p1-lacZ)] lacA::tet | BB2511 × pGB5 |

| GB1006 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(nprE396p1-lacZ)] lacA::tet | BB2511 × pGB6 |

| GB1033 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(aprE640p2-lacZ)] lacA::tet | BB2511 × pGB13 |

| GB1035 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(aprE334p+-lacZ)] lacA::tet | BB2511 × pGB14 |

| GB1047 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(nprE396p2-lacZ)] lacA::tet | BB2511 × pGB19 |

| GB1055 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(nprE153p+-lacZ)] lacA::tet | BB2511 × pGB21 |

| BB2676 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(dppAp+-lacZ)] lacA::tet | 47 |

| BB2770 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(ybgE292p+-lacZ)] lacA::tet | 62 |

| BB3550 | ΔamyE::[neo Φ(hutPp+-lacZ)646] lacA::tet | BB2511 × DNA(SF646) |

| BB3654 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(ispAp+-lacZ)] lacA::tet | 27 |

| BB4008 | ΔamyE::[erm Φ(aprE334p2-lacZ)] lacA::tet | BB2511 × pBB1829 |

The symbol “×” indicates transformation by plasmid or chromosomal DNA.

DNA manipulations.

Methods for common DNA manipulations, transformation, and sequence analysis were as previously described (46, 47). All oligonucleotides used in this work are described in Table 2. Chromosomal DNA of B. subtilis strain SMY or plasmids constructed in this work were used as templates for PCR. All cloned PCR-generated fragments were verified by sequencing.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this work

| Primer category and name | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Flanking forward primers | ||

| oBB67 | GCTTCTAAGTCTTATTTCC | erm (pHK23) |

| oGB1 | CGGACTCTAGAGCCTATGAATTCTCCATTTTCTTC | aprE640 |

| oGB5 | CGGACTCTAGAGAATCAGCAGGGTGCTTTG | nprE396 |

| oGB29 | GGACTCTAGAGCACACGCAGGTCATTTG | aprE334 |

| oGB37 | CGGACTCTAGACAACAAAAACAAACACAGGAC | nprE153 |

| Flanking reverse primers | ||

| oBB102 | CACCTTTTCCCTATATAAAAGC | lacZ (pHK23) |

| oGB2 | CGGGAAAGCTTGATCCACAATTTTTTGCTTCTCAC | aprE640/aprE334 |

| oGB6 | CGAGCAAGCTTAGACAATTTCTTACCTAAACCCAC | nprE396 |

| Internal mutagenic forward primers | ||

| oGB4 | CAATAAATTCACAccATAGTCTTTTAAG | aprEp1 |

| oGB8 | CAATATAAAGTTTTgAcTATTTTCAAAAAGGGG | nprEp1 |

| oGB22 | CAATAAATTCACAGAcTAGcCTTTTAAG | aprEp2 |

| oGB32 | GACTCATCTTGAccTTATTCAACA | nprEp2 |

| Internal mutagenic reverse primers | ||

| oGB3 | CTTAAAAGACTATggTGTGAATTTATTG | aprEp1 |

| oGB7 | CCCCTTTTTGAAAATAgTcAAAACTTTATATTG | nprEp1 |

| oGB23 | CTTAAAAGgCTAgTCTGTGAATTTATTG | aprEp2 |

| oGB33 | TGTTGAATAAggTCAAGATGAGTC | nprEp2 |

The altered nucleotides conferring mutations in the CodY-binding site are shown in lowercase. The restriction sites are underlined.

Construction of transcriptional fusions.

Plasmid pGB1 (aprE640p+-lacZ) was created by cloning the XbaI- and HindIII-treated PCR product, containing the entire aprE regulatory region, in pHK23 (erm), a plasmid that integrates at the amyE locus of the B. subtilis chromosome (47). A 0.66-kb aprE PCR product was synthesized by use of primers oGB1 and oGB2. Plasmid pGB14 (aprE334p+-lacZ), containing the same aprE regulatory region but truncated from the 5′ end, was constructed in a similar way by using oGB29 as the forward primer.

Plasmid pGB2 (nprE396p+-lacZ) was created as described above by cloning the 0.42-kb PCR product, which was synthesized with oGB5 and oGB6 as primers and contained the entire nprE regulatory region. Plasmid pGB21 (nprE153p+-lacZ), containing the nprE regulatory region truncated from the 5′ end, was constructed in a similar way by using oGB37 instead of oGB5.

Plasmids pGB5 (aprE640p1-lacZ), pGB6 (nprE396p1-lacZ), pGB13 (aprE640p2-lacZ), and pGB19 (nprE396p2), containing 2-bp substitution mutations in the CodY- or ScoC-binding site, were constructed as described above, using fragments generated by two-step overlapping PCR. In the first step, products containing the 5′ part of the corresponding regulatory regions were synthesized by using oligonucleotide oGB1 or oGB5 as the forward primer and mutagenic oligonucleotide oGB3 (aprEp1), oGB23 (aprEp2), oGB7 (nprEp1), or oGB33 (nprEp2) as the reverse primer. Products containing the 3′ part of the regulatory regions were synthesized by using mutagenic oligonucleotide oGB4 (aprEp1), oGB22 (aprEp2), oGB8 (nprEp1), or oGB32 (nprEp2) as the forward primer and oligonucleotide oGB2 or oGB6 as the reverse primer. The PCR products were used in a second, splicing step of PCR mutagenesis as overlapping templates to generate a modified fragment containing the entire aprE or nprE regulatory region; oligonucleotides oGB1 or oGB5 and oGB2 or oGB6 served as the forward and reverse PCR primers, respectively.

Plasmid pBB1829 (aprE334p2-lacZ) was constructed as described for pGB14, using pGB13 as the template for PCR.

B. subtilis strains carrying various lacZ fusions at the amyE locus (Table 1) were isolated after transforming strain BB2511 (amyE::spc lacA) with the appropriate plasmids by selecting for resistance to erythromycin conferred by the plasmids and screening for loss of the spectinomycin resistance marker, which indicated a double-crossover homologous recombination event. Strain BB2511 and all its derivatives have very low endogenous β-galactosidase activity due to a null mutation in the lacA gene (48).

Labeling of DNA fragments.

PCR products containing the regulatory regions of the aprE or nprE gene were synthesized using fusion-containing plasmids as templates and vector-specific oligonucleotides oBB67 and oBB102 as primers. oBB67 starts 96 bp upstream of the XbaI site used for cloning, and oBB102 starts 36 bp downstream of the HindIII site that serves as a junction between the promoters and the lacZ part of the fusions. The reverse primer, oBB102, which primed synthesis of the template strand of each PCR product, was labeled using T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP.

The procedures for gel shift and DNase I footprinting experiments were as described previously (41). Samples contained various amounts of proteins, a vast excess of unlabeled salmon sperm DNA, and ≤0.1 or 2 to 4 nM labeled DNA for gel shift or DNase I footprinting experiments, respectively.

Protein purification.

CodY-His5 was purified to near homogeneity as described previously (47).

Enzyme assays.

β-Galactosidase specific activity was determined as described previously (49).

RESULTS

CodY binding to the aprE regulatory region.

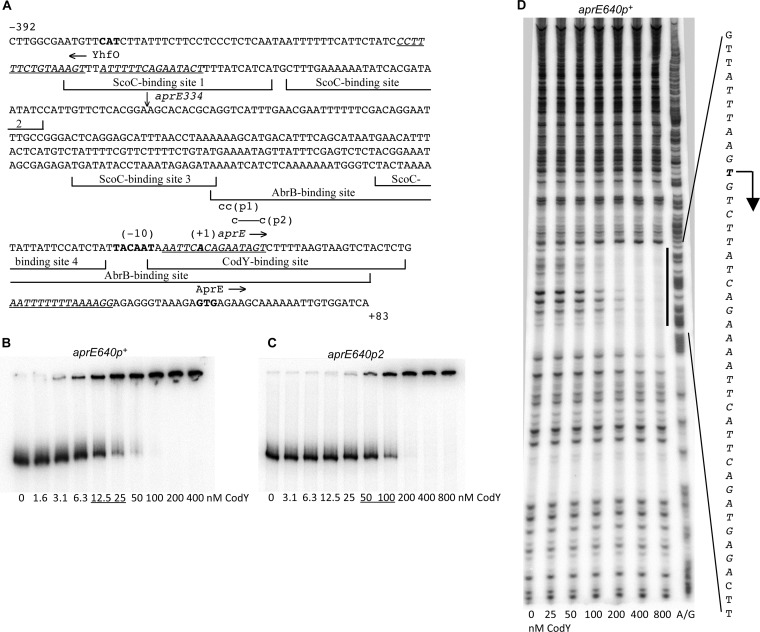

In gel shift experiments, purified CodY bound to a DNA fragment containing the entire aprE regulatory region (Fig. 1A) with a moderate to high affinity (apparent KD [equilibrium dissociation constant] of ~15 nM; the KD was estimated as the protein concentration needed to shift 50% of DNA fragments under conditions of a vast protein excess over DNA) (Fig. 1B). In general, nonspecific binding of CodY in gel shift experiments is observed only at 400 to 800 nM CodY (45, 50). Confirming the specificity of interaction, DNase I footprinting experiments showed that CodY protected a single region of DNA, located at positions −7 to +30 with respect to the aprE transcription start point (Fig. 1A and D). This sequence includes the core CodY-binding site, from positions +4 to +15, as determined by in vitro DNA affinity purification coupled with massively parallel sequencing (IDAP-Seq) (27). The aprE CodY-binding site also encompasses a 15-bp sequence (from positions −5 to +10) with 4 mismatches to the CodY-binding consensus motif, AATTTTCWGAAAATT (47, 51, 52) (Fig. 1A). (We use the terms “site” and “motif” to describe an experimentally determined location of CodY binding and a 15-bp sequence that is similar to the consensus motif, respectively; core sites include only positions that are essential for CodY binding.)

FIG 1.

Binding of CodY to the aprE regulatory region. (A) Sequence (5′ to 3′) of the coding (nontemplate) strand of the aprE regulatory region within the aprE640p+-lacZ fusion. Coordinates are reported with respect to the transcription start point (10). The upstream endpoints of inserts within the aprE640 and aprE334 fusions are at positions −557 and −251, respectively; the latter junction is indicated by a vertical arrow above the sequence. The downstream endpoints of both inserts coincide with the 3′ end of the presented sequence. The likely translation initiation codon, the −10 promoter region, and the apparent transcription start point are shown in bold. The directions of transcription and translation are indicated by horizontal arrows. The sequences that were protected by CodY (this work), ScoC (12), or AbrB (11) in DNase I footprinting experiments are shown by bracketed lines. The sequences of the four CodY-binding motifs, with three or four mismatches each, are italicized and underlined. The mutated nucleotides are shown in lowercase above the sequence. (B and C) Gel shift assays of CodY binding to aprE fragments. The aprE640p+ (B) and aprE640p2 (C) PCR fragments obtained with oligonucleotides oBB67 and oBB102, using pGB1 and pGB13, respectively, as templates, and labeled on the template strand were incubated with increasing amounts of purified CodY in the presence of 10 mM ILV. CodY concentrations used (monomers) are reported below the lanes; concentrations corresponding to the apparent KD for binding are underlined. (D) DNase I footprinting analysis of CodY binding to the aprE regulatory region. The aprE640p+ PCR fragment used for panel B was incubated with increasing amounts of purified CodY in the presence of 10 mM ILV and then with DNase I. The protected area is indicated by a vertical line, and the corresponding sequence is reported; the protected nucleotides are italicized. The apparent transcription start point and direction of transcription are shown by a bent arrow. CodY concentrations used (nanomolar [monomers]) are indicated below the lanes. The A+G sequencing ladder of the template DNA strand is shown in the right lane.

CodY- and ScoC-mediated regulation of the aprE gene.

An aprE640p+-lacZ transcriptional fusion including the entire intergenic region upstream of aprE and the first 25 bp of the coding sequence was constructed. Because aprE expression is strongly repressed during exponential growth in rich media by a transition state regulator, AbrB (10, 11), the strains used for the initial analysis of aprE expression, described in this and the next sections, contained an abrB null mutation. Efficient CodY binding to a sequence overlapping the transcription start point suggested that CodY may be a strong negative regulator of the aprE gene. Nevertheless, inactivation of CodY caused a ≤2-fold increase in expression of the aprE640p+-lacZ fusion in TSS glucose-ammonium medium containing a mixture of 16 amino acids (TSS+16 aa; see Materials and Methods) (Table 3, codY/codY+ ratio for strains BB3912 and BB3913); this medium is known to make CodY highly active (47, 53).

TABLE 3.

Expression of aprE-lacZ fusions in TSS+16 aa mediuma

| Strain | Fusion promoter | Relevant genotype | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units) | Fold regulation |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| codY/codY+ | scoC/scoC+ | ||||

| BB3912 | aprE640p+ | abrB | 6.08 | 1.9 | 1.5 |

| BB3913 | codY abrB | 11.5 | 16.9 | ||

| BB3914 | scoC abrB | 9.14 | 21.2 | ||

| BB3910 | codY scoC abrB | 194.2 | |||

| BB3933 | aprE640p1 | abrB | 12.8 | 0.08 | 1.7 |

| BB3934 | codY abrB | 1.01 | 17.5 | ||

| BB3965 | scoC abrB | 22.0 | 0.80 | ||

| BB3966 | codY scoC abrB | 17.7 | |||

| BB3935 | aprE640p2 | abrB | 127.5 | 0.09 | 1.5 |

| BB3936 | codY abrB | 11.3 | 15.4 | ||

| BB3937 | scoC abrB | 192.2 | 0.91 | ||

| BB3938 | codY scoC abrB | 174.3 | |||

| BB3939 | aprE334p+ | abrB | 9.00 | 21.3 | 1.1 |

| BB3941 | codY abrB | 191.7 | 0.90 | ||

| BB3940 | scoC abrB | 9.58 | 17.9 | ||

| BB3942 | codY scoC abrB | 171.7 | |||

| BB4013 | aprE334p2 | abrB | 179.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| BB4015 | codY abrB | 180.6 | 1.0 | ||

| BB4016 | scoC abrB | 180.9 | 1.0 | ||

| BB4017 | codY scoC abrB | 185.5 | |||

| GB1001 | aprE640p+ | Wild type | 1.62 | 3.1 | 1.8 |

| GB1009 | codY | 5.02 | 2.5 | ||

| GB1018 | scoC | 2.79 | 4.5 | ||

| GB1020 | codY scoC | 12.7 | |||

Cells were grown in TSS+16 aa medium, duplicate samples were taken at two time points during the exponential growth phase, and β-galactosidase specific activity was assayed and expressed in Miller units. All values are averages for the two time points from at least two independent experiments, and the relative standard errors of the means did not exceed 20%.

Even more surprisingly, expression of the aprE640p+-lacZ fusion in TSS+16 aa medium increased only about 1.5-fold in a scoC null mutant (Table 3, scoC/scoC+ ratio for strains BB3912 and BB3914), despite the fact that scoC was initially identified as a gene whose inactivation leads to strong derepression of the aprE gene and to a higher level of accumulation of subtilisin (16, 18, 37, 54). Importantly, in a codY scoC double null mutant, expression from the aprE promoter increased 21- or 17-fold over that seen in the single scoC or codY mutant strain, respectively (Table 3, strains BB3910, BB3913, and BB3914). We concluded that both CodY and ScoC are strong repressors of the aprE gene and that each is sufficient for efficient repression in the absence of the other. Moreover, given that the difference in aprE expression between the codY+ scoC+ strain, BB3912, and the codY scoC double mutant strain, BB3910, was only 32-fold (Table 3), the effects of CodY and ScoC on aprE are not multiplicative, in accord with the previous observation that the two proteins do not act completely independently of each other due to scoC repression by CodY (41).

CodY is mostly inactive in cells growing in the absence of exogenous amino acids (55). Therefore, in TSS glucose-ammonium medium, aprE640p+-lacZ expression was high in double codY scoC and single scoC mutant strains but remained strongly repressed in wild-type and codY single mutant strains, presumably due to high ScoC activity in both latter cases (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Expression of aprE640p+-lacZ fusion in minimal TSS mediuma

| Strain | Relevant genotype | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units) | Fold regulation |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| codY/codY+ | scoC/scoC+ | |||

| BB3912 | abrB | 13.1 | 0.83 | 23.5 |

| BB3913 | codY abrB | 10.9 | 31.1 | |

| BB3914 | scoC abrB | 307.9 | 1.1 | |

| BB3910 | codY scoC abrB | 338.8 | ||

Cells were grown in TSS medium without amino acids, and β-galactosidase specific activity was assayed as described in the footnote to Table 3.

Inactivation of the aprE ScoC- and CodY-binding sites.

To prove that the observed effects of CodY on aprE expression are direct and to unravel the mechanism of interaction between CodY and ScoC, we performed deletion and point mutational analyses of their binding sites.

To impair binding of ScoC, we constructed a fusion, aprE334p+-lacZ, that is similar to the aprE640p+-lacZ fusion but is truncated by 306 bp at the 5′ end. The deleted sequence included the upstream pair of ScoC-binding sites (two of four identified sites, from positions −324 to −295 and −292 to −267, by reference to the transcription start point) (Fig. 1A), which are required for efficient ScoC-mediated repression of aprE (9, 12, 18). Expression of this truncated fusion was not affected (0.9- to 1.1-fold regulation) by a scoC null mutation in either a codY+ or codY mutant strain (in the abrB background), confirming that ScoC interaction with the upstream binding sites is necessary for ScoC-mediated repression of aprE (Table 3). On the other hand, the fusion was 21-fold more active in the single codY null mutant strain than in the codY+ strain (Table 3), consistent with the prediction that the repressive nature of CodY would be revealed under conditions in which ScoC cannot exert its own repression.

We also introduced two double-substitution mutations into the CodY-binding site of the full-length aprE-lacZ fusion in such a way as to reduce the site's similarity to the consensus motif (Fig. 1) (the mutations are at positions +4 and +5 [the p1 version of the promoter region] or +6 and +10 [the p2 version] with respect to the transcription start point). In gel shift experiments, CodY bound the p2-containing regulatory region with a 4-fold-reduced affinity (Fig. 1C) (the p1-containing fragment was not tested). Both pairs of mutations abolished CodY-mediated repression of the promoter (0.8- to 0.9-fold versus 21-fold) as revealed by comparing expression levels in pairs of scoC mutant strains (BB3966 and BB3965 or BB3938 and BB3937), indicating that CodY binding to this region is directly responsible for regulation and that the other three CodY-binding motifs (i.e., potential binding sequences) present in the intergenic region (Fig. 1A) are not involved in regulation (Table 3). Neither mutation affected the extent of ScoC-mediated regulation (15- to 18-fold), as revealed by comparing double codY scoC and single codY mutant strains carrying the mutant fusions, which is consistent with the nonoverlapping arrangement of the CodY- and ScoC-binding sites (Table 3 and Fig. 1A) (see below for an additional discussion of the p1 mutation).

Expression of the mutant fusions in a codY+ scoC+ strain is high because fully active CodY represses scoC but is not able to bind to the mutant promoters. Importantly, comparing codY+ and codY mutant strains in a scoC+ background revealed that CodY acts as a strong positive regulator (>10-fold regulation) of the aprEp1 and aprEp2 promoters (Table 3, strain pair BB3933 and BB3934 or BB3935 and BB3936). Because this effect of CodY was abolished in scoC mutants, it must be indirect and due to reduced ScoC-mediated repression of the aprE promoter in codY+ cells.

As expected, the simultaneous removal of CodY- and ScoC-mediated repression by construction of the aprE334p2-lacZ fusion resulted in high-level, nearly constitutive expression from the mutant promoter (Table 3, strain BB4013 and derivatives).

We concluded that preventing direct CodY-mediated repression of the wild-type aprE promoter in TSS+16 aa medium is largely compensated for by increased repression resulting from the elevated level of ScoC. We also concluded that when CodY is highly active, the aprE promoter is repressed mostly by CodY and the contribution by ScoC is very small (1.5- to 1.6-fold). In other words, ScoC-mediated repression of the aprE gene is efficient only when CodY is inactive or absent.

In addition to eliminating CodY-mediated direct regulation, the p1 mutation pair also reduced (∼10-fold) the fully derepressed level of aprE640p1-lacZ expression in a codY scoC double null mutant (Table 3, strain BB3966). It is possible that p1 decreases the stability of the aprE-lacZ transcript because it is located in the sequence corresponding to the stem-loop structure in the 5′ untranslated leader sequence, which is important for maintaining the unusually long half-life of the aprE and aprE-lacZ mRNAs (56). Alternatively, the p1 mutation could affect the intrinsic activity of the aprE promoter by virtue of being very close to the transcription start point. Because it was introduced at positions corresponding to the two bulges of the stem-loop structure (56), the p2 mutation appeared to have less of an effect on mRNA stability, as suggested by high expression of the aprE640p2 and aprE334p2 fusions in a codY scoC background.

Contribution of AbrB to aprE expression.

In abrB+ cells that lacked CodY and ScoC, expression of the aprE640p+-lacZ fusion in TSS+16 aa medium was 15-fold lower than that in abrB mutant cells (Table 3, strains GB1020 and BB3910). CodY and ScoC together imposed an additional 8-fold repression of the aprE promoter (Table 3, strain GB1001). The maximal individual effects of CodY and ScoC were only 4.5- and 2.5-fold, respectively, i.e., much smaller than those in the absence of AbrB (Table 3). Both the CodY-binding site and the downstream ScoC-binding sites overlap the AbrB-binding site, located at positions −59 to +25 with respect to the aprE transcription start point (11) (Fig. 1A). Therefore, both CodY and ScoC may compete with AbrB for binding, though this possibility was not addressed experimentally.

The p1 and p2 mutations affected the regulation of aprE640-lacZ expression in the abrB+ background in a way similar to that in the abrB background; the expression levels of the mutant fusions in abrB+ cells were 9- to 14-fold lower than those in abrB mutant cells, and therefore the mutations did not substantially affect AbrB-dependent regulation (data not shown).

aprE expression in nutrient broth sporulation medium.

The lack of strong repression of aprE by ScoC in the wild-type strain under the growth conditions tested (Table 3) contrasts with several previous reports (9, 16, 18, 37, 54). The unexpected regulation is likely due to the constantly high activity of CodY during growth in TSS+16 aa medium (see Discussion). Under these conditions, which were not used previously to test ScoC-dependent regulation, both the aprE and scoC genes were strongly repressed by CodY.

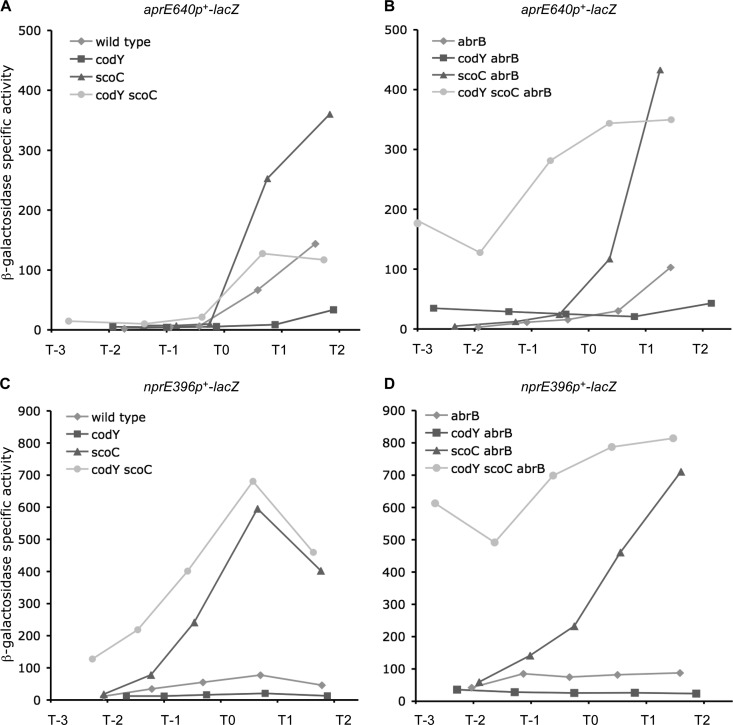

In DS nutrient broth sporulation medium, in which amino acids and other nutrients are exhausted during growth, expression from the aprE promoter in wild-type (abrB+) cells was low and increased only at the beginning of stationary phase (T0), when both AbrB and CodY were losing activity (Fig. 2A). As reported previously, aprE expression was higher in the absence of ScoC (Fig. 2A). In a codY mutant, aprE expression remained low at all stages of growth due to increased ScoC-mediated repression (Fig. 2A).

FIG 2.

Expression of the aprE640p+-lacZ and nprE396p+-lacZ fusions in DS nutrient broth medium. Cells were grown in DS medium, and samples for β-galactosidase determination were taken at the indicated times. Times are shown with respect to T0, i.e., the transition point between the exponential and stationary growth phases. At least two experiments were performed for each strain, and the results of a representative experiment are shown. Other biological replicates of each experiment gave very similar patterns of gene expression.

Despite the substantial differences in expression in TSS+16 aa medium (Table 3), expression levels from the aprEp+ promoter in DS medium were rather similar in wild-type and abrB cells (Fig. 2A and B). AbrB-mediated repression could be observed only at early stages of growth (before T0) in codY single mutant cells and, much more dramatically, in codY scoC double mutant cells (Fig. 2A and B).

Expression of the aprE640p+-lacZ fusion in abrB (codY+) strains remained low during exponential phase when CodY was highly active (Fig. 2B). After T0, expression from the aprE promoter increased moderately in the abrB strain (likely due to the exhaustion of CodY effectors and insufficient derepression of scoC to maintain aprE repression by ScoC) but much more sharply in the scoC abrB double mutant (Fig. 2B). Importantly, the codY scoC abrB triple mutant showed high aprE expression even at early stages of growth, before T0. A small increase in expression of the fusion at this stage of growth was observed even in codY abrB cells, though no further increase was seen at later stages of growth due to ScoC-mediated repression (Fig. 2B). We concluded that repression by either AbrB or CodY is sufficient for maintenance of low expression of aprE before T0 in DS medium. After T0, abrB+ and abrB strains behave similarly because abrB becomes repressed by Spo0A and preexisting AbrB becomes inactivated (11, 21, 57, 58). Thus, inactivation of CodY in a strain that is also defective in AbrB and ScoC is the only known condition that allows substantial aprE expression during exponential growth phase in a complex medium.

Expression of the aprE640p+-lacZ fusion reached higher levels in scoC strains than in codY scoC strains (Fig. 2A and B). This phenomenon was also observed for the aprE334p2-lacZ fusion, which is not regulated directly by either CodY or ScoC (data not shown), indicating the existence of another, unknown step at which CodY is indirectly and positively involved in regulation of aprE expression. Interestingly, CodY is only partly active at this growth stage in DS medium due to exhaustion of amino acids.

CodY binding to the nprE regulatory region.

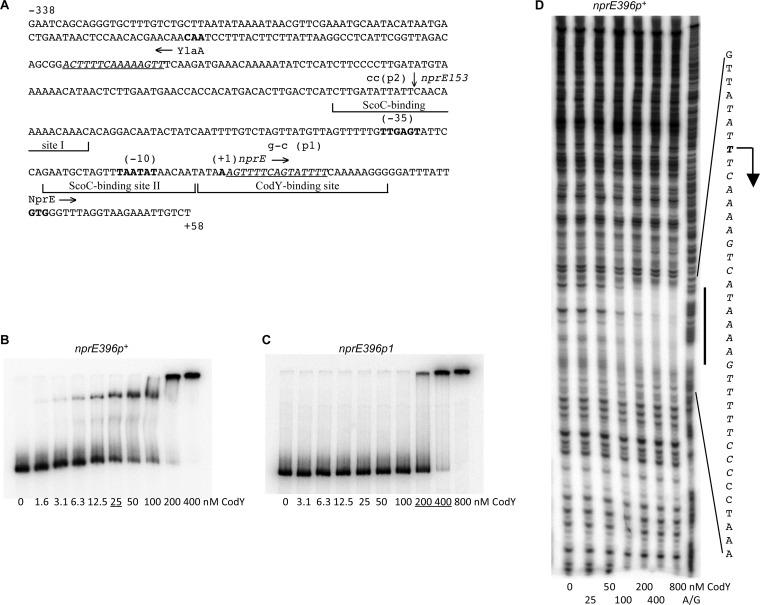

In gel shift experiments, purified CodY bound with a moderate affinity (apparent KD, ~25 nM) to a DNA fragment containing the entire nprE regulatory region (Fig. 3B). DNase I footprinting experiments showed that CodY protected a region of DNA from positions −3 to +25 with respect to the nprE transcription start point (Fig. 3A and D). This sequence includes the core CodY-binding site, from positions +3 to +21, as determined by IDAP-Seq (27). The nprE protected region also includes a 15-bp sequence (positions +2 to +16) that has 4 mismatches with respect to the CodY-binding consensus motif (Fig. 3A).

FIG 3.

Binding of CodY to the nprE regulatory region. (A) Sequence (5′ to 3′) of the coding (nontemplate) strand of the nprE regulatory region within the nprE396-lacZ fusion. The 5′ and 3′ nucleotides of the sequence presented correspond to the first and last nucleotides of the nprE insert within the fusion. Coordinates are reported with respect to the transcription start point (60). The upstream boundary of the nprE153-lacZ fusion, at position −95, is indicated by a vertical arrow above the sequence. The likely translation initiation codon, the −10 and −35 promoter regions, and the transcription start point are shown in bold. The directions of transcription and translation are indicated by horizontal arrows. The sequences that were protected by CodY or ScoC (12) in DNase I footprinting experiments are shown by bracketed lines. The sequences of the two CodY-binding motifs, with three or four mismatches each, are italicized and underlined. The mutated nucleotides are shown in lowercase above the sequence. (B and C) Gel shift assays of CodY binding to nprE fragments. The nprE396p+ (B) and nprE396p1 (C) DNA fragments obtained with oligonucleotides oBB67 and oBB102, using pGB2 and pGB6, respectively, as templates, and labeled on the template strand were incubated with increasing amounts of purified CodY in the presence of 10 mM ILV. CodY concentrations used (nanomolar [monomers]) are reported below the lanes; concentrations corresponding to the apparent KD for binding are underlined. (D) DNase I footprinting analysis of CodY binding to the nprE regulatory region. The nprE396p+ DNA fragment used for panel B was incubated with increasing amounts of purified CodY in the presence of 10 mM ILV and then with DNase I. The protected area is indicated by a vertical line, and the corresponding sequence is reported; the protected nucleotides are italicized. The apparent transcription start point and direction of transcription are shown by a bent arrow. CodY concentrations used (monomers) are indicated below the lanes. The A+G sequencing ladder of the template DNA strand is shown in the right lane.

CodY- and ScoC-mediated regulation of the nprE gene.

Binding of CodY to a region surrounding the transcription start point suggests that CodY is a negative regulator of the nprE gene. An nprE396p+-lacZ transcriptional fusion including the entire intergenic region upstream of nprE and the first 24 bp of the coding sequence was constructed. A 2.3-fold increase in expression of the fusion was observed in a scoC null mutant strain under our growth conditions (Table 5), reminiscent of the small increase reported above for the aprE fusion. Unexpectedly, expression of the nprE396p+-lacZ fusion in TSS+16 aa medium decreased 2.2-fold in a codY null mutant strain (Table 5). In contrast, in a codY scoC double mutant strain, expression from the nprE promoter increased 3.7- or 20-fold over its level in a single scoC or codY mutant strain, respectively (Table 5). We concluded that, as for aprE, both CodY and ScoC are strong repressors of the nprE gene and the effects of codY and scoC null mutations can be discerned only in the absence of the other regulator. The decreased expression of the nprE-lacZ fusion in a single codY mutant suggests that the elevated level of ScoC more than compensates for the absence of CodY. A similar, 2.5-fold positive regulation of nprE was observed in a global RNA-Seq analysis of the CodY regulon (28). Thus, in wild-type cells, by virtue of repressing scoC, CodY behaves as a net positive regulator of nprE.

TABLE 5.

Expression of nprE-lacZ fusions in TSS+16 aa mediuma

| Strain | Fusion promoter | Relevant genotype | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units) | Fold regulation |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| codY/codY+ | scoC/scoC+ | ||||

| GB1002 | nprE396p+ | Wild type | 20.1 | 0.45 | 2.3 |

| GB1010 | codY | 9.0 | 19.7 | ||

| GB1021 | scoC | 47.8 | 3.7 | ||

| GB1023 | codY scoC | 177.8 | |||

| BB3991 | abrB | 36. 1 | 0.31 | 3.0 | |

| BB4069 | abrB codY | 11.2 | 36.0 | ||

| BB4070 | abrB scoC | 107.4 | 3.8 | ||

| BB4073 | abrB codY scoC | 403.3 | |||

| GB1006 | nprE396p1 | Wild type | 111.9 | 0.18 | 3.3 |

| GB1014 | codY | 20.7 | 25.9 | ||

| GB1022 | scoC | 372.3 | 1.4 | ||

| GB1024 | codY scoC | 534.8 | |||

| GB1047 | nprE396p2 | Wild type | 29.3 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| GB1048 | codY | 44.7 | 3.7 | ||

| GB1049 | scoC | 44.2 | 3.8 | ||

| GB1050 | codY scoC | 166.4 | |||

| GB1055 | nprE153p+ | Wild type | 53.7 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| GB1056 | codY | 80.5 | 3.4 | ||

| GB1057 | scoC | 61.5 | 4.4 | ||

| GB1058 | codY scoC | 273.5 | |||

Cells were grown and β-galactosidase specific activity was assayed as described in the footnote to Table 3.

In DS nutrient broth sporulation medium, the expression pattern of the nprE396p+-lacZ fusion was similar, though not identical, to that of the aprE-lacZ fusion (Fig. 2C). The growth phase-dependent increase in expression was somewhat smaller, but the effect of a scoC mutation was stronger than that for the aprE gene. That is, derepression of the nprE promoter after T0 was 4- to 7-fold in wild-type cells but ∼30-fold in the scoC mutant; expression of the nprE-lacZ fusion before T0 was somewhat higher in wild-type cells, and especially in scoC mutant cells, than that of the aprE-lacZ fusion (Fig. 2C). A codY mutation had a negative effect on nprE expression, reflecting stronger repression by ScoC, but a codY scoC double mutant was derepressed, albeit to different extents, at all stages of growth (Fig. 2C).

A moderate, 2- to 5-fold increase in nprE396p+-lacZ expression was seen in an abrB null mutant strain grown in TSS+16 aa medium or DS nutrient broth medium (Table 5 and Fig. 2D), consistent with previous microarray results (59). Almost completely constitutive expression of the nprE-lacZ fusion was observed in the codY scoC abrB triple mutant in DS medium (Fig. 2D). No binding of AbrB to the nprE promoter was detected in vivo (59), indicating that the negative AbrB effect may be indirect.

Inactivation of the nprE CodY- and ScoC-binding sites.

To test whether the effect of CodY is direct and to figure out the relationship between CodY- and ScoC-mediated regulation of nprE, we sought to inactivate the CodY- and ScoC-binding sites of the nprE gene individually. A double-substitution mutation, p1, was introduced into the nprE396-lacZ fusion (mutations at positions +8 and +10 with respect to the transcription start point) in such a way as to reduce the similarity of the CodY-binding site to the consensus motif (Fig. 3A). Comparing strains GB1022 (scoC) and GB1024 (codY scoC), we found that the p1 mutation reduced CodY-mediated repression of the fusion (1.4-fold instead of 3.7-fold), suggesting that CodY binding to this region is directly responsible for regulation (Table 5). In gel shift experiments, CodY bound the p1-containing regulatory region with a >10-fold-reduced affinity, and no complex with an intermediate mobility was observed; the residual binding to the p1-containing region may be nonspecific (Fig. 3C). Importantly, the p1 mutation did not significantly affect ScoC-mediated repression (26- versus 20-fold) of the nprE gene (Table 5, strain pair GB1024 and GB1014 or GB1023 and GB1010), indicating that the mutated nucleotides are not involved in ScoC binding and that CodY and ScoC bind to different sites. The p1 mutation also increased 3.0-fold the fully derepressed level of expression in a codY scoC double null mutant, implying that the mutation affected the intrinsic activity of the nprE promoter due to its proximity to the transcription start point (Table 5 and Fig. 3A).

Two ScoC-binding sites were found in the regulatory region of the nprE gene (12). To impair ScoC binding, we constructed a fusion, nprE153p+-lacZ, that is similar to the nprE396p+-lacZ fusion but is truncated by 243 bp from the 5′ end. The deletion removed most of the upstream ScoC-binding site, which is necessary for ScoC-mediated repression of the nprE gene (12, 60). As predicted, expression of the truncated fusion was much less affected by a scoC null mutation than was expression of the longer fusion (3.4-fold compared to 20-fold), suggesting that ScoC binding to this region contributes significantly to repression of the nprE gene (Table 5, strains GB1056 and GB1058). The deletion did not affect regulation by CodY in the scoC background (Table 5, strains GB1057 and GB1058), indicating that the upstream 15-bp CodY-binding motif (positions −209 to −195 with respect to the transcription start point) (Fig. 3A) is not involved in regulation.

To confirm the location of the ScoC-binding site, we introduced a double-substitution mutation, p2 (mutations at positions −102 and −101), into the upstream ScoC-binding site of the nprE396-lacZ fusion in such a way as to reduce the site's similarity to the previously suggested ScoC-binding consensus motif, AATANTATT (Fig. 3) (12). In the codY null background, the p2 mutation strongly reduced ScoC-mediated repression of the fusion, from 20- to 3.7-fold (Table 5, strains GB1048 and GB1050). Neither the deletion nor the p2 mutation affected CodY-mediated regulation of nprE, again indicating that CodY and ScoC act at independent sites (Table 5).

Regulation of the ispA gene.

We have previously shown that the B. subtilis ispA gene, encoding an intracellular protease, is also under negative CodY control (27). Considering that expression of IspA in nutrient broth medium was reported to be under negative ScoC control (61), we expected the ispA gene to be under a form of regulation similar to that for aprE and nprE. However, we could not detect any substantial effect of a scoC null mutation on expression of an ispA-lacZ fusion in either a codY+ or codY null mutant strain in TSS+16 aa medium (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Effect of ScoC on expression of CodY-regulated fusionsa

| Strain | Fusion promoter | Relevant genotype | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BB3654 | ispA-lacZ | Wild type | 0.11 |

| BB3875 | scoC | 0.17 | |

| BB3659 | codY | 12.3 | |

| BB3879 | codY scoC | 14.1 | |

| BB3550 | hutP-lacZ | Wild type | 0.45 |

| BB3873 | scoC | 0.48 | |

| BB3899 | codY | 9.32 | |

| BB3900 | codY scoC | 9.91 | |

| BB2781 | dppA-lacZ | abrB | 6.28 |

| BB3921 | scoC abrB | 5.42 | |

| BB2786 | codY abrB | 373.8 | |

| BB3922 | codY scoC abrB | 249.8 | |

| BB2770 | ybgE292-lacZ | Wild type | 1.12 |

| BB3918 | scoC | 1.05 | |

| BB2771 | codY | 427.8 | |

| BB4089 | codY scoC | 442.0 |

Cells were grown and β-galactosidase specific activity was assayed as described in the footnote to Table 3. Histidine (0.1%) was added to the medium in experiments with the hutP-lacZ fusion to induce promoter expression. The dppA-lacZ fusion was tested in abrB mutant cells to abolish AbrB-mediated repression of the dppA promoter (35). The activity of endogenous β-galactosidase was ≤0.05 Miller unit.

Potential reciprocal effect of ScoC on CodY activity.

Published and unpublished DNA microarray data indicated that several genes and operons that are direct targets of CodY repression, such as hutP, ilvB, yxbB, dppA, hom, amhX, bcaP, ilvA, yxbC, putB, appD, yodF, and rapA, are expressed at 3- to 20-fold lower levels in a scoC null mutant than in a wild-type strain (16, 26–28). Such an effect could mean that CodY synthesis or activity is directly or indirectly reduced by ScoC.

To test this potential effect of ScoC on CodY, we measured the expression of lacZ fusions to three known CodY-dependent promoters, i.e., those of hutP, dppA, and ybgE (36, 53, 62). None of these fusions was affected by a scoC mutation in TSS+16 aa medium or in DS nutrient broth medium (Table 6 and data not shown); the derepressed level of expression of these fusions in codY null mutant cells was also not affected by the absence of ScoC (Table 6). Our experiments rule out the possibility of a reciprocal, negative interaction between the two regulators, at least under the growth conditions tested. The reason for the downregulation of several CodY-dependent genes in the published microarray experiment remains unknown. A possible explanation is based on the medium used (2× SNB [16], which contains twice the concentration of Difco nutrient broth as that in DS medium). In the absence of ScoC, increased uptake of oligopeptides (present at a relatively high concentration in SNB medium) occurs due to derepressed levels of ScoC-regulated permeases (39, 41). Subsequent intracellular degradation of the oligopeptides and their conversion to amino acids would lead to elevated activity of CodY.

DISCUSSION

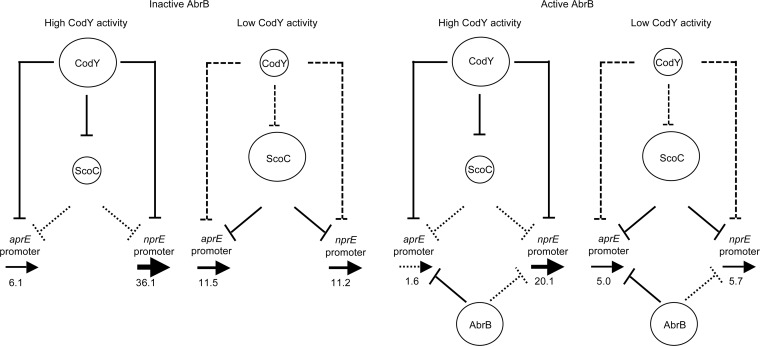

In this work, we showed that two genes, aprE and nprE, encoding major extracellular proteases of B. subtilis, are subject to very similar but unusual and complex forms of regulation by two transcriptional regulators, CodY and ScoC. Simultaneous inactivation of three negative regulators, AbrB, CodY, and ScoC, or the latter two regulators is required to observe high aprE or nprE expression, respectively, under conditions of nutrient excess.

Both CodY (this work) and ScoC (12) bind to the regulatory regions of these genes and repress their transcription. In addition, we have shown previously that CodY binds to the regulatory region of scoC and represses its transcription (41). Such an arrangement of two regulators, where one of them negatively regulates expression of the other and both of them negatively regulate expression of the same target gene, has been termed a type 2 incoherent feed-forward loop (63, 64). Though feed-forward loops are very common, type 2 incoherent loops are less so (63). Type 2 indicates that all direct interactions within the loop are negative. The term “incoherent” reflects the fact that CodY, in addition to being a direct negative regulator of aprE and nprE, serves as an indirect positive regulator of the same genes by preventing high-level expression of ScoC. Interestingly, other regulators of aprE form several more feed-forward loops in which both AbrB and ScoC directly repress the sinIR operon and SinR directly represses degU (12, 65–67). Additionally, both AbrB and ScoC are subject to negative autoregulation, and DegU is positively autoregulated (41, 68, 69).

Because scoC expression increases when CodY is inactive or absent, stronger ScoC-mediated repression can compensate for the loss of CodY-mediated repression. As a result, only a mild increase in aprE expression was observed in codY mutants in a defined amino acid-containing medium (Fig. 4). Interestingly, expression from the nprE promoter decreased in codY mutants, implying that repression of nprE by a derepressed level of ScoC is stronger than that by CodY (Fig. 4). The strong negative role of CodY in aprE and nprE regulation could be observed only in the absence of ScoC or by impairing ScoC binding to the promoters (Tables 3 and 5).

FIG 4.

Model of regulation of the aprE and nprE promoters by the combined actions of CodY, ScoC, and AbrB. The sizes of the circles reflect the relative amounts of the active forms of the proteins. The solid vertical lines indicate relatively strong effects on transcription. Dotted lines indicate relatively weak effects on transcription. The boldness of the horizontal arrows indicates the relative strengths of transcription of the target genes, and the numbers show activities of the corresponding lacZ fusions during exponential growth in TSS+16 aa medium.

Similarly, the strong negative role of ScoC in regulation of the aprE and nprE promoters could be observed only when CodY was absent or unable to bind to the promoters (Tables 3 to 5). This result contrasts with several previous reports that demonstrated negative regulation of aprE and nprE or the corresponding enzymes by ScoC (16, 18, 37, 54). The unexpected response of the aprE and nprE promoters to a scoC null mutation in our experiments was likely due to high activity of CodY during growth in TSS+16 aa medium. Under these conditions, the genes remain repressed by CodY even if ScoC is absent (Fig. 4). Apparently, in most previous studies of aprE and nprE regulation, expression of the genes was tested during late stages of growth in rich complex media, when exhaustion of nutrients rendered CodY partly inactive. As a result, the aprE and nprE genes would remain repressed because of the elevated levels of ScoC, and mutational inactivation of ScoC would reveal a high level of ScoC-mediated regulation. This is what we observed by evaluating the effects of the scoC mutation on the expression of aprE- and nprE-lacZ fusions in DS medium (Fig. 2).

The strong negative contributions of CodY and ScoC to aprE regulation explain why aprE expression is only weakly increased in abrB mutants grown under conditions of nutrient excess. The nature of AbrB as a repressor was historically revealed only in spo0A null mutant cells (10, 70), in which AbrB stays active after T0, whereas CodY is at least partially inactivated. Still, it is uncertain why ScoC does not compensate for the loss of CodY and AbrB under such conditions, especially given that scoC expression is increased in the absence of Spo0A (71).

The B. subtilis opp operon, encoding an oligopeptide permease, and the braB gene, encoding a branched-chain amino acid permease, as well as the scoC gene itself, are also subject to combined direct repression by CodY and ScoC (41, 42). A second B. subtilis oligopeptide permease operon, app, and the bac operon, encoding the antibiotic bacilysin, are also subject to dual repression by CodY and ScoC, though the mechanisms of their regulation have not been determined; the pks operon, encoding the antibiotic bacillaene, may also be under dual regulation by CodY and ScoC (16, 26–28, 39, 72, 73; unpublished data). Interestingly, each of the promoters jointly repressed by CodY and ScoC displays its own distinct pattern of expression, which likely depends on the relative contributions to regulation and the relative affinities of binding of the two proteins. In the case of braB, the repressive effects of CodY and ScoC are almost identical in magnitude, and each of the two regulators fully compensates for the loss of the other. This effect contributes to an unusual pattern of braB expression, in which the highest expression level is observed at intermediate levels of CodY activity (42). On the other hand, ScoC-mediated repression of opp is more efficient than CodY-mediated repression and is detectable, although at a reduced level, even in codY+ cells (41). In contrast, negative regulation of the scoC gene by CodY was almost fully detectable in scoC+ cells (41). Additionally, CodY and ScoC compete for binding at the oppA and braB promoters but not at the aprE, nprE, and scoC promoters (41, 42).

AprE, one of the most extensively studied proteins of B. subtilis, has proved to be under unusually complex regulation, including direct transcriptional control by a positive factor, DegU∼P, and four negative factors, AbrB, ScoC, SinR, and CodY. The activity of each regulator is determined directly or indirectly by different physiological conditions and may cause heterogeneity in aprE expression in the cell population (69). The nature of the physiological signals affecting the activities of AbrB, ScoC, DegU, and SinR remains unknown. Thus, CodY is the only regulator of the aprE and nprE genes for which specific signals that affect its regulatory activity (ILV and GTP) have been identified. In addition, the apparent role of the stringent response in aprE regulation may be mediated at least partly through CodY (74). That is, synthesis of (p)ppGpp occurs when one or more amino acids become limiting and leads to a reduction in the cellular GTP pool (75). As a result, CodY activity decreases under conditions of stringency.

The exact contributions of AbrB, CodY, and ScoC to repression of aprE and nprE are likely to depend on the composition of the medium, the extent of nutrient exhaustion, and the growth stage, all of which affect the exact timing of CodY and AbrB inactivation. AbrB-mediated repression is relieved when Spo0A is activated by phosphorylation (21, 76). The multicomponent nature of the phosphorelay allows integrate multiple environmental signals in determining the extent of Spo0A activation and, as a result, AbrB inactivation. CodY-mediated repression is relieved when the concentrations of amino acids in the growth medium decrease substantially (35, 36). In DS medium, the consequent reduction in CodY activity occurs at roughly the same time that Spo0A is activated. ScoC expression gradually increases as a result of CodY inactivation (41). However, it remains unclear under which physiological conditions, if any, ScoC-mediated repression of nprE and aprE is relieved in wild-type cells; in codY mutant cells, expression of aprE and nprE fusions in DS medium remained low at all stages of growth, suggesting that ScoC was continually active. Although AbrB is able to bind the scoC regulatory region (11) and is reported to activate the expression of this gene (71), the activity of a scoC-lacZ fusion was not affected by an abrB null mutation in TSS+16 aa medium (41). It remains unknown how additional regulatory inputs, e.g., through the SalA-mediated regulation of scoC expression (18, 22), affect ScoC activity and the interaction between ScoC and CodY.

Because AbrB appears to be active under all growth conditions in which Spo0A remains inactive, the roles of CodY and ScoC in aprE expression may be restricted to growth conditions that lead to the activation of Spo0A and relief from the AbrB-mediated repression. Because nprE expression is regulated by AbrB less tightly than aprE expression (Tables 3 and 5 and Fig. 2), the roles of CodY and ScoC in NprE expression appear to be important under a wider range of growth conditions. Due to their nonidentical regulation and timing of expression, the two major exoproteases of B. subtilis may have different physiological functions.

We recently showed that expression of two minor extracellular proteases, Vpr and Mpr, is also under direct negative CodY control (41), though neither vpr nor mpr is under ScoC-mediated control. Thus, CodY is a direct negative regulator of at least four B. subtilis extracellular proteases. Expression of exoproteases from Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes was also reported to be under CodY control, and some of these proteases may be involved in virulence (77, 78). Repression of genes coding for extracellular proteases under conditions of nutrient excess not only prevents the waste of energy needed to synthesize and secrete proteases but also limits the amino acid supply and leads to the reduced activity of CodY through a negative-feedback loop.

Interestingly, it is possible that the abundance of oligopeptides in the natural environment of B. subtilis is higher than the abundance of free amino acids. Therefore, the benefits of tight coordination of protein degradation, oligopeptide transport, and ILV uptake (due to the ScoC-mediated repression of braB [42]), all of which affect CodY activity, may provide a rationale for the intimate regulatory interplay between CodY and ScoC.

Funding Statement

The content of this work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health or NIGMS.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pero J, Sloma A. 1993. Proteases, p 939–952. In Sonenshein AL, Hoch JA, Losick R (ed), Bacillus subtilis and other Gram-positive bacteria. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Margot P, Karamata D. 1996. The wprA gene of Bacillus subtilis 168, expressed during exponential growth, encodes a cell-wall-associated protease. Microbiology 142:3437–3444. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-12-3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawamura F, Doi RH. 1984. Construction of a Bacillus subtilis double mutant deficient in extracellular alkaline and neutral proteases. J Bacteriol 160:442-444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lanigan-Gerdes S, Dooley AN, Faull KF, Lazazzera BA. 2007. Identification of subtilisin, Epr and Vpr as enzymes that produce CSF, an extracellular signalling peptide of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 65:1321–1333. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corvey C, Stein T, Dusterhus S, Karas M, Entian KD. 2003. Activation of subtilin precursors by Bacillus subtilis extracellular serine proteases subtilisin (AprE), WprA, and Vpr. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 304:48–54. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00529-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kada S, Ishikawa A, Ohshima Y, Yoshida K. 2013. Alkaline serine protease AprE plays an essential role in poly-gamma-glutamate production during natto fermentation. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 77:802–809. doi: 10.1271/bbb.120965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stephenson K, Bron S, Harwood CR. 1999. Cellular lysis in Bacillus subtilis; the affect of multiple extracellular protease deficiencies. Lett Appl Microbiol 29:141–145. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765X.1999.00592.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang MY, Ferrari E, Henner DJ. 1984. Cloning of the neutral protease gene of Bacillus subtilis and the use of the cloned gene to create an in vitro-derived deletion mutation. J Bacteriol 160:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henner DJ, Ferrari E, Perego M, Hoch JA. 1988. Location of the targets of the hpr-97, sacU32(Hy), and sacQ36(Hy) mutations in upstream regions of the subtilisin promoter. J Bacteriol 170:296–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrari E, Henner DJ, Perego M, Hoch JA. 1988. Transcription of Bacillus subtilis subtilisin and expression of subtilisin in sporulation mutants. J Bacteriol 170:289–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strauch MA, Spiegelman GB, Perego M, Johnson WC, Burbulys D, Hoch JA. 1989. The transition state transcription regulator abrB of Bacillus subtilis is a DNA binding protein. EMBO J 8:1615–1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kallio PT, Fagelson JE, Hoch JA, Strauch MA. 1991. The transition state regulator Hpr of Bacillus subtilis is a DNA-binding protein. J Biol Chem 266:13411–13417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaur NK, Oppenheim J, Smith I. 1991. The Bacillus subtilis sin gene, a regulator of alternate developmental processes, codes for a DNA-binding protein. J Bacteriol 173:678–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strauch MA, Hoch JA. 1993. Transition-state regulators: sentinels of Bacillus subtilis post-exponential gene expression. Mol Microbiol 7:337–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogura M, Yamaguchi H, Yoshida K, Fujita Y, Tanaka T. 2001. DNA microarray analysis of Bacillus subtilis DegU, ComA and PhoP regulons: an approach to comprehensive analysis of B. subtilis two-component regulatory systems. Nucleic Acids Res 29:3804–3813. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.18.3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caldwell R, Sapolsky R, Weyler W, Maile RR, Causey SC, Ferrari E. 2001. Correlation between Bacillus subtilis scoC phenotype and gene expression determined using microarrays for transcriptome analysis. J Bacteriol 183:7329–7340. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.24.7329-7340.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mader U, Antelmann H, Buder T, Dahl MK, Hecker M, Homuth G. 2002. Bacillus subtilis functional genomics: genome-wide analysis of the DegS-DegU regulon by transcriptomics and proteomics. Mol Genet Genomics 268:455–467. doi: 10.1007/s00438-002-0774-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogura M, Matsuzawa A, Yoshikawa H, Tanaka T. 2004. Bacillus subtilis SalA (YbaL) negatively regulates expression of scoC, which encodes the repressor for the alkaline exoprotease gene, aprE. J Bacteriol 186:3056–3064. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.10.3056-3064.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobayashi K. 2007. Gradual activation of the response regulator DegU controls serial expression of genes for flagellum formation and biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 66:395–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrari E, Jarnagin AS, Schmidt BF. 1993. Commercial production of extracellular enzymes, p 917–937. In Sonenshein AL, Hoch JA, Losick R (ed), Bacillus subtilis and other Gram-positive bacteria. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banse AV, Chastanet A, Rahn-Lee L, Hobbs EC, Losick R. 2008. Parallel pathways of repression and antirepression governing the transition to stationary phase in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:15547–15552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805203105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Derouiche A, Shi L, Bidnenko V, Ventroux M, Pigonneau N, Franz-Wachtel M, Kalantari A, Nessler S, Noirot-Gros MF, Mijakovic I. 2015. Bacillus subtilis SalA is a phosphorylation-dependent transcription regulator that represses scoC and activates the production of the exoprotease AprE. Mol Microbiol 97:1195–1208. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abe S, Yasumura A, Tanaka T. 2009. Regulation of Bacillus subtilis aprE expression by glnA through inhibition of scoC and sigma(D)-dependent degR expression. J Bacteriol 191:3050–3058. doi: 10.1128/JB.00049-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bai U, Mandic-Mulec I, Smith I. 1993. SinI modulates the activity of SinR, a developmental switch protein of Bacillus subtilis, by protein-protein interaction. Genes Dev 7:139–148. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogura M, Shimane K, Asai K, Ogasawara N, Tanaka T. 2003. Binding of response regulator DegU to the aprE promoter is inhibited by RapG, which is counteracted by extracellular PhrG in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 49:1685–1697. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molle V, Nakaura Y, Shivers RP, Yamaguchi H, Losick R, Fujita Y, Sonenshein AL. 2003. Additional targets of the Bacillus subtilis global regulator CodY identified by chromatin immunoprecipitation and genome-wide transcript analysis. J Bacteriol 185:1911–1922. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.6.1911-1922.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belitsky BR, Sonenshein AL. 2013. Genome-wide identification of Bacillus subtilis CodY-binding sites at single-nucleotide resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:7026–7031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300428110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brinsmade SR, Alexander EL, Livny J, Stettner AI, Segre D, Rhee KY, Sonenshein AL. 2014. Hierarchical expression of genes controlled by the Bacillus subtilis global regulatory protein CodY. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:8227–8232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321308111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guedon E, Serror P, Ehrlich SD, Renault P, Delorme C. 2001. Pleiotropic transcriptional repressor CodY senses the intracellular pool of branched-chain amino acids in Lactococcus lactis. Mol Microbiol 40:1227–1239. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petranovic D, Guedon E, Sperandio B, Delorme C, Ehrlich D, Renault P. 2004. Intracellular effectors regulating the activity of the Lactococcus lactis CodY pleiotropic transcription regulator. Mol Microbiol 53:613–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shivers RP, Sonenshein AL. 2004. Activation of the Bacillus subtilis global regulator CodY by direct interaction with branched-chain amino acids. Mol Microbiol 53:599–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ratnayake-Lecamwasam M, Serror P, Wong KW, Sonenshein AL. 2001. Bacillus subtilis CodY represses early-stationary-phase genes by sensing GTP levels. Genes Dev 15:1093–1103. doi: 10.1101/gad.874201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Handke LD, Shivers RP, Sonenshein AL. 2008. Interaction of Bacillus subtilis CodY with GTP. J Bacteriol 190:798–806. doi: 10.1128/JB.01115-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brinsmade SR, Sonenshein AL. 2011. Dissecting complex metabolic integration provides direct genetic evidence for CodY activation by guanine nucleotides. J Bacteriol 193:5637–5648. doi: 10.1128/JB.05510-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slack FJ, Mueller JP, Strauch MA, Mathiopoulos C, Sonenshein AL. 1991. Transcriptional regulation of a Bacillus subtilis dipeptide transport operon. Mol Microbiol 5:1915–1925. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slack FJ, Serror P, Joyce E, Sonenshein AL. 1995. A gene required for nutritional repression of the Bacillus subtilis dipeptide permease operon. Mol Microbiol 15:689–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higerd TB, Hoch JA, Spizizen J. 1972. Hyperprotease-producing mutants of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 112:1026–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dod B, Balassa G. 1978. Spore control (sco) mutations in Bacillus subtilis. III. Regulation of extracellular protease synthesis in the spore control mutations scoC. Mol Gen Genet 163:57–63. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koide A, Perego M, Hoch JA. 1999. ScoC regulates peptide transport and sporulation initiation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 181:4114–4117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kodgire P, Dixit M, Rao KK. 2006. ScoC and SinR negatively regulate epr by corepression in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 188:6425–6428. doi: 10.1128/JB.00427-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belitsky BR, Barbieri G, Albertini AM, Ferrari E, Strauch MA, Sonenshein AL. 2015. Interactive regulation by the Bacillus subtilis global regulators CodY and ScoC. Mol Microbiol 97:698–716. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Belitsky BR, Brinsmade SR, Sonenshein AL. 2015. Intermediate levels of Bacillus subtilis CodY activity are required for derepression of the branched-chain amino acid permease, BraB. PLoS Genet 11:e1005600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeigler DR, Pragai Z, Rodriguez S, Chevreux B, Muffler A, Albert T, Bai R, Wyss M, Perkins JB. 2008. The origins of 168, W23, and other Bacillus subtilis legacy strains. J Bacteriol 190:6983–6995. doi: 10.1128/JB.00722-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Belitsky BR, Sonenshein AL. 2011. Contributions of multiple binding sites and effector-independent binding to CodY-mediated regulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 193:473–484. doi: 10.1128/JB.01151-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis TJ. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Belitsky BR, Sonenshein AL. 2008. Genetic and biochemical analysis of CodY-binding sites in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 190:1224–1236. doi: 10.1128/JB.01780-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daniel RA, Haiech J, Denizot F, Errington J. 1997. Isolation and characterization of the lacA gene encoding beta-galactosidase in Bacillus subtilis and a regulator gene, lacR. J Bacteriol 179:5636–5638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Belitsky BR, Sonenshein AL. 1998. Role and regulation of Bacillus subtilis glutamate dehydrogenase genes. J Bacteriol 180:6298–6305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Belitsky BR, Sonenshein AL. 2011. CodY-mediated regulation of guanosine uptake in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 193:6276–6287. doi: 10.1128/JB.05899-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guedon E, Sperandio B, Pons N, Ehrlich SD, Renault P. 2005. Overall control of nitrogen metabolism in Lactococcus lactis by CodY, and possible models for CodY regulation in Firmicutes. Microbiology 151:3895–3909. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.den Hengst CD, van Hijum SA, Geurts JM, Nauta A, Kok J, Kuipers OP. 2005. The Lactococcus lactis CodY regulon: identification of a conserved cis-regulatory element. J Biol Chem 280:34332–34342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fisher SH, Rohrer K, Ferson AE. 1996. Role of CodY in regulation of the Bacillus subtilis hut operon. J Bacteriol 178:3779–3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dod B, Balassa G, Raulet E, Jeannoda V. 1978. Spore control (sco) mutations in Bacillus subtilis. II. Sporulation and the production of extracellular protease and α-amylase by scoC mutants. Mol Gen Genet 163:45–56. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Slack FJ, Mueller JP, Sonenshein AL. 1993. Mutations that relieve nutritional repression of the Bacillus subtilis dipeptide permease operon. J Bacteriol 175:4605–4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hambraeus G, Karhumaa K, Rutberg B. 2002. A 5′ stem-loop and ribosome binding but not translation are important for the stability of Bacillus subtilis aprE leader mRNA. Microbiology 148:1795–1803. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-6-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.O'Reilly M, Devine KM. 1997. Expression of AbrB, a transition state regulator from Bacillus subtilis, is growth phase dependent in a manner resembling that of Fis, the nucleoid binding protein from Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 179:522–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kobir A, Poncet S, Bidnenko V, Delumeau O, Jers C, Zouhir S, Grenha R, Nessler S, Noirot P, Mijakovic I. 2014. Phosphorylation of Bacillus subtilis gene regulator AbrB modulates its DNA-binding properties. Mol Microbiol 92:1129–1141. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chumsakul O, Takahashi H, Oshima T, Hishimoto T, Kanaya S, Ogasawara N, Ishikawa S. 2011. Genome-wide binding profiles of the Bacillus subtilis transition state regulator AbrB and its homolog Abh reveals their interactive role in transcriptional regulation. Nucleic Acids Res 39:414–428. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Toma S, Del Bue M, Pirola A, Grandi G. 1986. nprR1 and nprR2 regulatory regions for neutral protease expression in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 167:740–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruppen ME, Van Alstine GL, Band L. 1988. Control of intracellular serine protease expression in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 170:136–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Belitsky BR, Sonenshein AL. 2011. Roadblock repression of transcription by Bacillus subtilis CodY. J Mol Biol 411:729–743. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mangan S, Alon U. 2003. Structure and function of the feed-forward loop network motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:11980–11985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2133841100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alon U. 2007. Network motifs: theory and experimental approaches. Nat Rev Genet 8:450–461. doi: 10.1038/nrg2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Strauch MA. 1995. In vitro binding affinity of the Bacillus subtilis AbrB protein to six different DNA target regions. J Bacteriol 177:4532–4536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shafikhani SH, Mandic-Mulec I, Strauch MA, Smith I, Leighton T. 2002. Postexponential regulation of sin operon expression in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 184:564–571. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.2.564-571.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ogura M, Yoshikawa H, Chibazakura T. 2014. Regulation of the response regulator gene degU through the binding of SinR/SlrR and exclusion of SinR/SlrR by DegU in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 196:873–881. doi: 10.1128/JB.01321-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Strauch MA, Perego M, Burbulys D, Hoch JA. 1989. The transition state transcription regulator AbrB of Bacillus subtilis is autoregulated during vegetative growth. Mol Microbiol 3:1203–1209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Veening JW, Igoshin OA, Eijlander RT, Nijland R, Hamoen LW, Kuipers OP. 2008. Transient heterogeneity in extracellular protease production by Bacillus subtilis. Mol Syst Biol 4:184. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Trowsdale J, Chen SM, Hoch JA. 1979. Genetic analysis of a class of polymyxin resistant partial revertants of stage 0 sporulation mutants of Bacillus subtilis: map of the chromosome region near the origin of replication. Mol Gen Genet 173:61–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00267691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Perego M, Hoch JA. 1988. Sequence analysis and regulation of the hpr locus, a regulatory gene for protease production and sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 170:2560–2567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Inaoka T, Wang G, Ochi K. 2009. ScoC regulates bacilysin production at the transcription level in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 191:7367–7371. doi: 10.1128/JB.01081-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vargas-Bautista C, Rahlwes K, Straight P. 2014. Bacterial competition reveals differential regulation of the pks genes by Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 196:717–728. doi: 10.1128/JB.01022-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hata M, Ogura M, Tanaka T. 2001. Involvement of stringent factor RelA in expression of the alkaline protease gene aprE in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 183:4648–4651. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.15.4648-4651.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lopez JM, Dromerick A, Freese E. 1981. Response of guanosine 5′-triphosphate concentration to nutritional changes and its significance for Bacillus subtilis sporulation. J Bacteriol 146:605–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Strauch M, Webb V, Spiegelman G, Hoch JA. 1990. The Spo0A protein of Bacillus subtilis is a repressor of the abrB gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87:1801–1805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rivera FE, Miller HK, Kolar SL, Stevens SM, Shaw LN. 2012. The impact of CodY on virulence determinant production in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Proteomics 12:263–268. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McDowell EJ, Callegari EA, Malke H, Chaussee MS. 2012. CodY-mediated regulation of Streptococcus pyogenes exoproteins. BMC Microbiol 12:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zalieckas JM, Wray LV Jr, Ferson AE, Fisher SH. 1998. Transcription-repair coupling factor is involved in carbon catabolite repression of the Bacillus subtilis hut and gnt operons. Mol Microbiol 27:1031–1038. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Steinmetz M, Richter R. 1994. Plasmids designed to alter the antibiotic resistance expressed by insertion mutations in Bacillus subtilis, through in vivo recombination. Gene 142:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Barbieri G, Voigt B, Albrecht D, Hecker M, Albertini AM, Sonenshein AL, Ferrari E, Belitsky BR. 2015. CodY regulates expression of the Bacillus subtilis extracellular proteases Vpr and Mpr. J Bacteriol 197:1423–1432. doi: 10.1128/JB.02588-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]