Abstract

Dyke-Davidoff-Masson syndrome (DDMS) is a rare disease which is clinically characterized by hemiparesis, seizures, facial asymmetry, and mental retardation. The classical radiological findings are cerebral hemiatrophy, calvarial thickening, and hyperpneumatization of the frontal sinuses. This disease is a rare entity, and it mainly presents in childhood. Adult presentation of DDMS is unusual and has been rarely reported in the medical literature.

Key Messages

DDMS is a rare disease of childhood. However, it should be kept in mind as a diagnostic possibility in an adult who presents with a long duration of progressive hemiparesis with seizures and mental retardation. Cerebral hemiatrophy, calvarial thickening, and hyperpneumatization of the frontal sinuses are diagnostic for this illness on brain imaging.

Key Words: Dyke-Davidoff-Masson syndrome, Cerebral hemiatrophy, Calvarial thickening

Introduction

Dyke-Davidoff-Masson syndrome (DDMS) is a rare disease comprising hemiparesis, seizures, facial asymmetry, and mental retardation [1]. The classical findings including cerebral hemiatrophy along with calvarial thickening and hyperpneumatization of the frontal sinuses are only found if an insult to the brain occurs before 3 years of age [2]. The major concern of the disease remain the intractable seizures for which drug therapy is not sufficient in most of the cases, and a surgical approach is necessary. However, if the patient presents later in life, the presentation may not be similar to that seen in childhood, and management changes accordingly.

Case Report

A 42-year-old woman presented to our outpatient department with a history of left partial motor seizures with occasional secondary generalization, left-side hemiparesis, and mental retardation since 2.5 years of age. She was born out of a nonconsanguineous marriage. Birth history was indicative of a full-term normal delivery without any antenatal or perinatal complications. She had normal developmental milestones during infancy and the second year of life. However, she had a history of febrile illness with seizures at the age of 28 months, for which she was treated in a local hospital as a case of meningoencephalitis, and she was discharged subsequently after 1 month on antiepileptic medications. However, she continued to have seizures which exacerbated due to poor compliance and other precipitating factors like sleep deprivation, stress, etc. Besides, the parents also noted learning difficulties, slurred speech, facial deviation, and progressive left hemiparesis, for which she was treated conservatively by a local practitioner. Her seizures did not respond to several antiepileptic medications in different combinations. However, the seizure frequency had decreased over the past 3–4 years, and, at the time of presentation, the patient was on a single antiepileptic drug without any episode of seizures for the past year. Notwithstanding, the patient's hemiparesis had worsened gradually with increased stiffness in the left extremities and poor dexterity of the left hand. The patient had also complained of diminished vision of the left eye 2–3 years previously, which was later established as homonymous hemianopia of the left eye field on clinical examination and visual field charting. Additionally, she had been on antidepressant medications for the past 8 years, her depression being improved for the past 2–3 years. Her examination did not reveal any neurocutaneous markers. She scored poorly on the Mini-Mental Status Examination (12/30) and had a left-sided spastic hemiparesis with brisk tendon reflexes and extensor plantar response. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was subsequently done, which revealed almost complete atrophy of the right cerebral hemisphere (fig. 1) along with an enlarged frontal sinus and thickening of the calvarium on the same side (fig. 2a, b) and mild crossed cerebellar hemiatrophy on the left side (fig. 2c, d). We accordingly kept a diagnosis of DDMS and managed her conservatively with muscle relaxants like baclofen and physiotherapy as well as counseling, after which her symptoms improved.

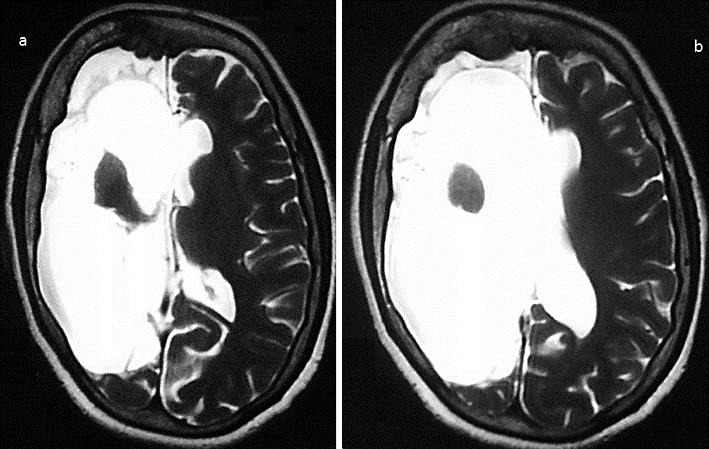

Fig. 1.

T2-weighted axial MRI showing cerebral hemiatrophy on the right side of the brain at the level of the basal ganglia (a) and at the supraganglionic level (b).

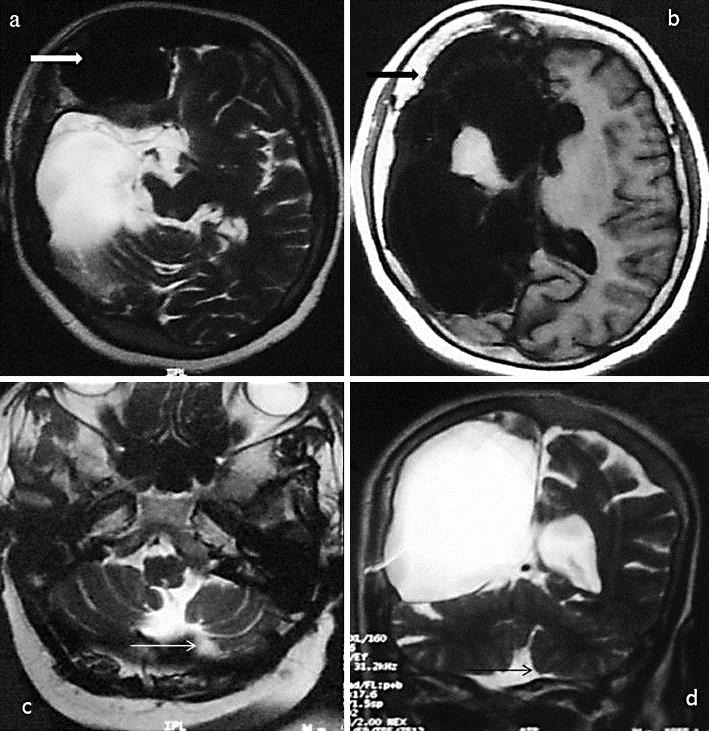

Fig. 2.

MRI of the brain showing frontal sinus hypertrophy in an axial T2-weighted sequence (thick white arrow; a) along with calvarial thickening in an axial T1-weighted sequence (thick black arrow; b). Crossed cerebellar hemiatrophy is evident on the left side in axial T2-weighted (thin white arrow; c) and coronal T2-weighted images (thin black arrow; d).

Discussion

This rare condition derives its name from the researchers Dyke, Davidoff, and Masson who first reported the condition way back in 1933. They described plain skull radiographic changes in 9 patients who presented with seizures, facial asymmetry, hemiparesis, and mental retardation [1]. Subtotal or diffuse cerebral hemiatrophy is a classical imaging finding. However, unilateral focal atrophy may occasionally be noted in the cerebral peduncles and the thalamic, pontine, crossed cerebellar, and parahippocampal regions. Brain imaging may additionally reveal prominent cortical sulci, dilated lateral ventricles and cisternal space, calvarial thickening, ipsilateral osseous hypertrophy with hyperpneumatization of the sinuses (mainly frontal and mastoid air cells), and an elevated temporal bone [2]. The clinical features include contralateral hemiparesis with an upper motor neuron type of facial palsy, focal or generalized seizures, and mental retardation along with learning disabilities [3]. There is no sex predilection, and any side of the brain can be involved, although involvement of the left side and male gender have been shown to be more common in one study [2].

Out of the two identified types of cerebral hemiatrophy, the infantile or congenital variety results from neonatal or gestational vascular occlusion involving the middle cerebral artery, unilateral cerebral arterial circulation anomalies, coarctation of the mid-aortic arch, or infections, and patients become symptomatic in the perinatal period or infancy. The acquired type results from various causes like birth asphyxia, prolonged febrile seizures, trauma, tumor, infection, ischemia, and hemorrhage [4, 5]. The classical MRI changes of this disease occur only if there is a brain insult due to the various causes listed above before 3 years of age [6].

To understand the genesis of the brain pathology in this syndrome one needs to look into the development of the brain minutely. The formation of the brain sulci starts around the fourth month of gestation and gets completed by the end of the eighth month. Overall, the maximum growth of a child's head occurs in the early years due to outward pressure of the enlarging human brain on the bony skull table which reaches half of its adult size at the end of infancy and three fourths of the adult size by the end of 3 years [7]. Therefore, only when brain damage is sustained before 3 years of age, other structures overlying the brain grow inward, thus resulting in an increased width of the diploic spaces, enlarged sinuses, and an elevated orbital roof, which are characteristic of this disorder [6]. The plausible mechanism of cerebral atrophy and the related progressive neurodeficit is hypothesized to be due to several ischemic episodes resulting from different causes, which reduce the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factors, which in turn leads to cerebral atrophy [8].

This patient had the acquired variety of the disease as the patient's complaints started after an episode of meningoencephalitis at the age of 28 months. There was a progressive increase in spasticity on the left side and impairment of dexterity of the left upper limb along with the development of homonymous hemianopia. Our patient strikingly had complete right cerebral hemiatrophy, which is atypical for the disease, especially for the acquired variety. Although initially the patient had progressive symptoms in the form of intractable seizures, later, in spite of a progressive loss of dexterity, the frequency of seizures decreased, which is atypical for this condition, as the classical presentation of this disease itself is intractable seizures. However, the natural course of this disease in adults has not been described in detail earlier due to the paucity of adult presentation; nevertheless, there have been pediatric case reports where, despite progression of the disease in the form of hemiatrophy of the brain and hemiparesis, the seizure frequency was dramatically reduced [9].

As previous imaging was not available in our patient, it is difficult to know with certainty whether the complete hemiatrophy originated from childhood or whether there was any progression of atrophy later in life; however, the decrease in the seizure frequency points towards a progressive atrophy later. The reasons for this lie in an interesting hypothesis, which has its roots in research evidence. Researchers have shown that recurrent seizures, especially intractable ones, may lead to damage of the brain [10, 11], and, subsequently, atrophy may accordingly ensue in those cases.

The progressive loss in dexterity as seen in our case can be explained on the basis of hemispherectomy models, which show that hand movements are more under the control of corticospinal pathways than leg movements [12]. Hemispherectomy has also been traditionally used as a therapeutic principle for intractable seizures in the early stage of this disease. In a way, near-complete hemiatrophy would lead to a similar therapeutic effect, which may explain the decrease in the seizure frequency in our case [13]. In summary, chronic hemiatrophy of the brain in our case perhaps resulted in a ‘functional hemispherectomy’ leading to this clinical picture. Homonymous hemianopia, as seen in our case, has been reported previously in scientific studies [14]. MRI findings were classical in our case and have been described earlier [2, 14]. However, as the patient presented in adulthood with a long-standing disease, her presentation was atypical. There have been only a few reports of cases of DDMS in adulthood in the medical literature [15].

The differential diagnosis of this syndrome includes Sturge-Weber syndrome, Rasmussen encephalitis, Silver-Russell syndrome, basal ganglia germinoma, Fishman syndrome, and linear nevus syndrome. Most of these, however, can be differentiated by performing a thorough clinical examination and by neuroimaging [16, 17]. Sturge-Weber syndrome (encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis) is characterized clinically by facial cutaneous vascular malformations (port-wine nevus), seizures, glaucoma, mental retardation, and recurrent stroke-like episodes. The underlying pathology includes intracranial vascular anomaly and leptomeningeal angiomatosis with stasis resulting in ischemia underlying the leptomeningeal angiomatosis, leading to intracranial tram track calcification with laminar cortical necrosis and atrophy [18]. Rasmussen encephalitis, a chronic progressive immune-mediated disorder of children between 6 and 8 years of age, also presents with intractable focal epilepsy and cognitive defects with similar imaging findings of hemispheric atrophy, but calvarial changes are not seen [19]. Silver-Russell syndrome is characterized by the classical facial phenotype (triangular face, small pointed chin, broad forehead, and thin wide mouth), poor growth with delayed bone age, clinodactyly, hemihypertrophy with normal head circumference, and normal intelligence [20]. Basal ganglia germinoma, a rare tumor of the brain, also frequently presents with progressive hemiparesis and cerebral hemiatrophy. However, imaging reveals cystic areas, focal hemorrhages, and mild surrounding edema along with calvarial changes [21]. Fishman syndrome or encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis is a rare neurocutaneous syndrome including unilateral cranial lipoma with lipodermoid of the eye, which presents usually with seizures. Neuroimaging, however, shows a calcified cortex and hemiatrophy [22]. The hallmarks of linear nevus syndrome are typically facial nevus, recurrent seizures, mental retardation, and unilateral ventricular dilatation resembling cerebral hemiatrophy [23].

Conclusion

For DDMS cases presenting in early childhood, refractory seizures remain the usual concern. Accordingly, hemispherectomy is the treatment of choice with a success rate of 85% in selected cases [24]. However, if the presentation is late as in our case and if seizures are under control, the patient can be kept on antiepileptic medications in spite of surgery, along with supportive therapy including physiotherapy, speech therapy, and occupational therapy. Further longitudinal studies are required to ascertain the natural course of this syndrome especially in an adult population, which would help in planning strategies regarding the time and nature of interventions and management accordingly.

Statement of Ethics

The subject of this case report gave her informed consent for the publication of this article.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Dyke CG, Davidoff LM, Masson CB. Cerebral hemiatrophy and homolateral hypertrophy of the skull and sinuses. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1933;57:588–600. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unal O, Tombul T, Cirak B, Anlar O, Incesu L, Kayan M. Left hemisphere and male sex dominance of cerebral hemiatrophy (DDMS) Clin Imaging. 2004;28:163–165. doi: 10.1016/S0899-7071(03)00158-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Afifi AK, Godersky JC, Menezes A, et al. Cerebral hemiatrophy, hypoplasia of internal carotid artery and intracranial aneurysm. Arch Neurol. 1987;44:232–235. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1987.00520140090024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sener RN, Jinkins JR. MR of craniocerebral hemiatrophy. Clin Imaging. 1992;16:93–97. doi: 10.1016/0899-7071(92)90119-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stred SE, Byrum CJ, Bove EL, Oliphant M. Coarctation of midaortic arch presenting with monoparesis. Ann Thorac Surg. 1986;42:210–212. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)60522-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solomon GE, Hilal SK, Gold AP, Carter S. Natural history of acute hemiplegia of childhood. Brain. 1970;93:107–120. doi: 10.1093/brain/93.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham A, Molnar Z. Development of the nervous system. In: Standring S, editor. Gray's Anatomy. ed 40. London: Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier; 2008. p. 385. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ono K, Komai K, Ikeda T. Dyke-Davidoff-Masson syndrome manifested by seizure in late childhood: a case report. J Clin Neurosci. 2003;10:367–371. doi: 10.1016/s0967-5868(03)00011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JH, Lee ZI, Kim HK, Kwon SH. A case of Dyke-Davidoff-Masson syndrome in Korea. Korean J Pediatr. 2006;49:208–211. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kälviäinen R, Salmenperä T, Partanen K, Vainio P, Riekkinen P, Pitkänen A. Recurrent seizures may cause hippocampal damage in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 1998;50:1377–1382. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kälviäinen R, Salmenperä T. Do recurrent seizures cause neuronal damage? A series of studies with MRI volumetry in adults with partial epilepsy. Prog Brain Res. 2002;135:279–295. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(02)35026-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Empelen R, Jennekens-Schinkel A, Buskens E, Helders PJ, van Nieuwenhuizen O, Dutch Collaborative Epilepsy Surgery Programme Functional consequences of hemispherectomy. Brain. 2004;127:2071–2079. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devlin AM, Cross JH, Harkness W, Chong WK, Harding B, Vargha-Khadem F, et al. Clinical outcomes of hemispherectomy for epilepsy in childhood and adolescence. Brain. 2003;126:556–566. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Algahtani HA, Aldarmahi AA, Al-Rabia MW, Young GB. Crossed cerebro-cerebellar atrophy with Dyke Davidoff Masson syndrome. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2014;19:52–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biçici V, Ekiz T, Bingöl I, Hatipoğlu C. Dyke-Davidoff-Masson syndrome in adulthood: a 50-year diagnostic delay. Neurology. 2014;83:1121. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao KC. Degenerative diseases and hydrocephalus. In: Lee SH, Rao KC, Zimmerman RA, editors. Cranial MRI and CT. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1999. pp. 212–214. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zilkha A. CT of cerebral hemiatrophy. Am J Roentgenol. 1980;135:259–262. doi: 10.2214/ajr.135.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas-Sohl KA, Vaslow DF, Maria BL. Sturge-Weber syndrome: a review. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;30:303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2003.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheybani L, Schaller K, Seeck M. Rasmussen encephalitis: an update. Schweiz Arch Neurol Psychiatr. 2011;162:225–231. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiu BP, Shi CH. Silver-Russel syndrome: a case report. World J Pediatr. 2007;3:68–70. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moon WK, Chang KH, Kim IO, Han MH, Choi CG, Suh DC, Yoo SJ, Han MC. Germinomas of the basal ganglia and thalamus: MR findings and a comparison between MR and CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:1413–1417. doi: 10.2214/ajr.162.6.8192009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amar DJ, Kornberg AJ, Smith LJ. Encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis (Fishman syndrome): a rare neurocutaneous syndrome. J Pediatr Child Health. 2000;36:603–605. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2000.00541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacoby CG, Go RT, Hahn FJ. Computed tomography in cerebral hemiatrophy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1977;129:5–7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.129.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Narain NP, Kumar R, Narain B. Dyke-Davidoff-Masson syndrome. Indian Pediatr. 2008;45:927–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]