Abstract

Mexican-origin adolescent mothers face numerous social challenges during dual-cultural adaptation that are theorized to contribute to greater depressive symptoms. Alongside challenges, there are familial resources that may offer protection. As such, the current study examined the trajectories of depressive symptoms among 204 Mexican-origin adolescent mothers (Mage = 16.80, SD = 1.00) across a 4-year period (3rd trimester of pregnancy, and 10, 24, and 36 months postpartum). Further, we examined the within-person relations of two unique sources of stress experienced during the dual-cultural adaptation process, acculturative and enculturative stress, and youths’ depressive symptoms; we also tested whether adolescent mothers’ perceptions of warmth from their own mothers emerged as protective. Adolescent mothers reported a decline in depressive symptoms after the transition to parenthood. Acculturative and enculturative stress emerged as significant positive within-person predictors of depressive symptoms. Maternal warmth emerged as a protective factor in the relation between enculturative stressors and depressive symptoms; however, for acculturative stressors, the protective effect of maternal warmth only emerged for U.S.-born youth. Findings illustrate the multi-dimensionality of stress experienced during the cultural adaptation process and a potential mechanism for resilience among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers.

Keywords: acculturative stress, enculturative stress, maternal warmth, adolescent mothers, depressive symptoms

Research indicates that adolescent mothers display greater depressive symptoms than nulliparous adolescent females and females who enter motherhood later in life (Lanzi et al., 2009; Mollborn & Morningstar, 2009). Adolescent mothers are theorized to display greater mental health problems, like depressive symptoms, because they often come from low socioeconomic backgrounds (Deal & Holt, 1998; Levine Coley & Chase-Lansdale, 1997), have restrictions on educational opportunities (Moore & Brooks-Gunn, 2002), and are balancing the normative challenges of adolescence while also becoming a mother (Birkland Thompson, & Phares, 2005). Adolescent pregnancy and the emergence of depressive symptoms during the transition to motherhood is of serious concern, given educational and economic restrictions that these adolescents face, and that maternal depressive symptoms, more generally, have serious developmental consequences for their young children (e.g., Cassidy, Zoccolillo, & Hughs, 1996; Field, 1992; Hodgkinson, Colantuoni, Roberts, Berg-Cross & Belcher, 2010; Weinberg & Tronick, 1998). A particularly vulnerable group in the U.S. is the Latina population. Estimates suggest that Latinas have the highest birthrate of all females between the ages 15 to 19 years old (70.5 per 1,000; National Vital Statistics Report, 2012), and some research suggests that Latina mothers are at greater risk for depressive symptoms compared to European American mothers (Howell, Mora, Horowitz, & Leventhal, 2007). Despite these statistics, very little research has documented how Latina adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms change across the transition to motherhood. Understanding intra-individual changes in depressive symptoms among this population is important because it provides valuable information about the long-term functioning of a high-risk group.

In addition to understanding changes in depressive symptoms among Latina adolescent mothers, it is important to understand how environmental risk and protective factors may inform their depressive symptoms over time. A risk and resilience framework (Masten, Best & Garmezy, 1990) and classic models of stress, support, and coping (Cohen, Gotlieb, & Underwood, 2004; Cohen & Willis, 1985) suggest that individuals face numerous environmental stressors that contribute to the development of depressive symptoms, but also can draw on needed resources and support from within the family. For Latino adolescents, an important environmental factor to consider is the cultural context; Latino youth develop within contexts in which dual-cultural adaptation processes are at play and such processes can bring about experiences of stress theorized to impact youths’ psychological functioning (Gonzales, Germán, & Fabrett, 2012). The experience of stress related to cultural adaptation, however, is not the only force at work; Latino youth draw resources from the strong familial relations that are common in this sociocultural context (Cauce & Domenech Rodriguez, 2002). For Latina adolescent mothers, many of whom are living with their families of origin, the processes by which cultural adaptation stressors and familial resources impact psychological functioning might be especially relevant (Contreras, Narang, Ikhlas, & Teichman, 2002). Surprisingly, little empirical work has examined cultural adaptation processes and familial resources among Latina adolescent mothers (Contreras, López, Rivera-Mosquera, Raymond-Smith, & Rothstein, 1999), and to our knowledge no study has examined cultural adaptation stressors longitudinally and in relation to depressive symptoms. Understanding these processes over time is critical to furthering our knowledge of stress in ethnic minority at-risk youth more broadly, and informing our understanding of risk and resilience in Latina adolescent mothers.

The current study focuses on Mexican-origin adolescent mothers and builds on our understanding of Latina adolescents’ psychological functioning by examining (a) longitudinal changes in depressive symptoms across a 4-year period from adolescents’ third trimester of pregnancy to three years postpartum, (b) how within-person fluctuations in two aspects of stressors associated with dual-cultural adaptation, acculturative and enculturative stress, were related to changes in depressive symptoms, and (c) if within-person reports of adolescents’ own mothers’ warmth moderated the associations between cultural adaptation stressors (i.e., acculturative and enculturative stress) and depressive symptoms.

Depressive Symptoms Trajectories in Adolescent Mothers

Prevalence estimates suggest that somewhere between 28 – 48% of adolescent mothers report high depressive symptoms (e.g., Deal & Holt, 1998; Leadbeater & Linares, 1992), which is considerably higher than the percentages of non-pregnant/-parenting adolescents and older mothers with high depressive symptoms (Mollborn & Morningstar, 2009; Figueiredo, Pacheco & Costa, 2007). Empirical work has documented numerous factors thought to contribute to adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms; specifically, factors that predate adolescents’ childbearing, such as low-socioeconomic status (Deal & Holt, 1998; Mollborn & Morningstar), and factors that are present during the transition to parenthood, such as being unmarried and remaining single (e.g., Kalil & Kunz, 2002), have been identified as possible contributors.

Despite a growing awareness of prevalence rates and factors that relate to adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms, much less work has focused on adolescent mothers’ intra-individual changes in depressive symptoms during the transition to parenthood. Research with adult mothers suggests that depressive symptoms generally decline from pregnancy to postpartum (e.g., Ritter, Hobfoll, Lavin, Cameron, & Hulsizer, 2000; Beeghly et al., 2002; Gump et al., 2009). The limited longitudinal work with adolescent mothers has reported a similar trend (Brown, Harris, Woods, Buman & Cox, 2012; Leadbeater & Linares, 1992; Milan et al., 2004), but findings differed slightly based on the spacing between assessments. For instance, Milan and colleagues (2004) examined African American, European American, and Latina adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms during their 3rd trimester, 6 months, 12 months, and 18 months postpartum and found that symptoms declined initially, increased from 6 months to 12 months, and then declined again. Brown and colleagues (2012) examined African American and Latina adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms at birth, 3 months, and 12 months postpartum, and found that mothers’ symptoms declined.

Few longitudinal studies have examined changes in adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms beyond 18 months postpartum (see Leadbeater & Linares, 1992, and Schmidt, Wieman, Rickert & Smith, 2006, for exceptions). For adolescent mothers in particular, understanding changes in depressive symptoms as they enter early adulthood is important because many mothers are facing new transitions that can include moving into their own home and, in some cases, having more children (Moore & Brooks-Gunn, 2002). Further, although longitudinal studies of adolescent mothers have included Latina participants (e.g., Milan et al., 2004; Brown et al., 2012; Leadbeater & Linares, 1992) and even Mexican American participants (Schmidt et al., 2006), most of these studies have utilized ethnic heterogeneous designs, with a focus on comparing Latinas to other ethnic/racial groups. As numerous scholars have pointed out, ethnic homogeneous designs allow for the examination of within-group variability in processes and are essential for building our understanding of risk and resilience within specific ethnic minority populations (García Coll et al., 1996; Knight, Roosa & Umaña-Taylor, 2009; McLoyd, 1998). To address these limitations, the current study focused specifically on Mexican-origin adolescent mothers from their third trimester of pregnancy to 36 months postpartum.

Acculturative and Enculturative Stress

In addition to the normative developmental processes at play during adolescence, Mexican-origin youth, and Latino youth more broadly, are tasked with the process of dual-cultural adaptation. That is, they are navigating multiple sets of expectations, values, and norms within the mainstream culture and their culture of origin (Gonzales et al., 2012). The process of adapting to the mainstream values, expectations, and norms, is referred to as acculturation. The process of retaining values, expectations, and norms of an individual’s and/or family’s country of origin is referred to as enculturation (Berry, 2003). Although the processes are related, they are theorized to be distinct, allowing for individuals to display simultaneously high levels of both, low levels of both, or differing patterns (Gonzales et al.). Given that the transition to parenthood may bring about a heightened sense of cultural socialization (Hughes, Rodriguez, Smith, Johnson, & Stevenson, 2006), adolescent mothers might be especially attuned to the process of dual-cultural adaptation because they are now tasked with the cultural socialization of their child.

The dual-cultural adaption process can bring about opportunities for some youth; however, for others, it can bring about distress (Gonzales et al., 2012; Wang, Schwartz, & Zamboanga, 2010). For instance, stress can arise from the acculturation process that includes difficulty learning English and the pressure to adopt and endorse mainstream values. Stress can also arise from the enculturative process that includes inability to speak Spanish or not speak it well, and increasing pressure from family members to retain the values of their culture of origin (Gonzales et al., 2012; Rodriquez, Myers, Mira & Garcia-Hernandez, 2002). Although immigrant or early generation youth might be more likely to experience acculturative stress and later generation youth more likely to experience enculturative stress, the dynamic process of dual-cultural adaptation makes it possible that youth face both sources of stress simultaneously in differing contexts (e.g., peer contexts, family context), and that their experiences with each source of stress changes across time as the process of cultural adaptation plays out (Rodriquez et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2010).

In line with general stress and depression theories (Hammen, 2005), stress experienced during the process of dual-cultural adaptation is theorized to contribute to greater depressive symptoms (Rodriquez et al., 2002; Schwartz et al., 2009). Despite a growing attention to both aspects of dual-cultural adaptation (Gonzales et al., 2012; Rodriquez et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2010), empirical studies examining stressors associated with the process have overwhelmingly focused exclusively on aspects of the acculturation process. These studies find a consistent positive relation between acculturative stress and individuals’ adjustment. For instance, acculturative stress has been found to relate to individuals’ alcohol and drug use (Zamboanga, Schwartz, Jarvis, & Van Tyne, 2009), anxiety symptoms (Suarez-Morales & Lopez, 2009), and depressive symptoms (Crockett, Iturbide, Stone, McGinley, Raffaelli, & Carlo, 2007; Sirin, Ryce, Gupta, & Rogers-Sirin, 2013). There are a small number of studies that have included stressors from the enculturative process in their conceptualization of acculturative stress1, and found that this combined stress construct is related to greater internalizing symptoms (Romero & Roberts, 2003; Torres, Driscoll, & Voell, 2012; Umaña-Taylor, Updegraff, & Gonzales-Backen, 2011). Only two studies to date, however, have assessed stressors from both the acculturative and enculturative process as unique predictors of individuals’ adjustment. In a sample of Latino adults, primarily of Mexican descent and foreign-born (79%), it was high levels of acculturative stress (i.e., English competency pressures) that related to clinical levels of depressive symptoms (Torres, 2010). However, in a Cuban college-age sample, primarily U.S.-born (77%), it was aspects of enculturative stress (i.e., Spanish competency pressures and pressures against acculturation) that were predictive of internalizing symptoms (Wang, Schwartz, & Zamboanga, 2010).

In addition to the limitation of only assessing aspects of acculturative stress, the larger cultural adaptation stress literature has been based primarily on cross-sectional findings (for exceptions, see Buchanan & Smokowski, 2009; Sirin et al., 2013; and Nair et al., 2013). Although cross-sectional analyses provide important information about associations, they present only a snap-shot and capture between-person relations. Stress process and depression theories suggest that the mechanisms through which stressors impact individuals’ depressive symptoms are a within-person process; individuals react to fluctuations in their own stress levels (Abela & Hankin, 2009; Hankin, 2012). Only longitudinal data have the ability to disaggregate between- and within-person effects (Curran & Bauer, 2010). Thus, although prior work suggests that increases in individuals’ acculturative stress, and to a lesser extent enculturative stress, are associated with greater depressive symptoms (e.g., Crockett et al., 2007; Torres et al., 2012), the within-person associations between these constructs have yet to be tested. Understanding how individuals’ depressive symptoms are related to their own fluctuations in dual-cultural adaptation stress provides a strong test of the theoretical proponents of the psychological consequences associated with the stressors of cultural adaptation. Further, focusing on both aspects of stress, acculturative and enculturative, as independent contributors to youths’ psychological adjustment, treats the experiences of youths as a complex, bi-dimensional process, much like the larger cultural adaptation literature (Gonzales et al., 2012).

Maternal Warmth as a Protective Factor

The risk and resilience framework (Masten, Best, Garmezy, 1990; Garmezy, 1993), and models of stress, support, and coping (Cohen & Wills, 1985) suggest that supportive and warm relationships within the family are important resources for individuals facing stress. Supportive and warm family relationships are thought to be an asset to children and adolescents, directly relating to positive adjustment and lower levels of mental health problems (a main effects model; Masten, 2001; Cohen & Willis, 1985). Further, supportive and warm family relationships can operate as a protective factor, counteracting or buffering the effects of stress on children and adolescents’ well-being (an interaction model; Masten, 2001; Masten et al., 1990; Cohen & Willis, 1985). Among Latino youth, the family unit is theorized to play an especially important role (Fuller & García Coll, 2010; Gonzales et al., 2012). Latino culture is characterized by a high level of interdependence within the family and familial values that emphasize solidarity, support, and obligation toward family members (Sabogal, Marín, Otero-Sabogal, Marín, & Perez-Stable, 1987). This emphasis is believed to positively impact Latino youth by providing additional resources during the cultural socialization process (Hernández, Conger, Robins, Bacher, & Widaman, in press) and buffering the negative effects of cultural stressors, such as acculturative stress (Gonzales et al., 2012). That is, Latino youth developing within families in which they feel supported and close to their parents are less likely to exhibit depressive symptoms, and when challenges arise, may be less likely to be negatively impacted because they can draw on support from the parent-adolescent relationship.

Among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers, familial relations and resources, particularly from their own mother (referred to hereafter as grandmothers), are thought to be especially important (Contreras et al. 2002). Grandmothers serve a central role in Latino families by providing emotional support and guidance to other family members (Cox, Brooks, & Valcarcel, 2000). For adolescent mothers, the transition to parenthood might further illuminate the importance of grandmothers, as the need for additional support and help emerges (Contreras et al., 2002). Further, as adolescent mothers wrestle with stressors associated with the cultural adaptation process, grandmothers might serve as an important emotional resource, lessening the impact of stress on adolescents’ depressive symptoms.

Empirically, numerous studies suggest that close and supportive relationships with mothers relate to better adolescent psychological functioning and have the potential to buffer the effects of stress during adolescence (e.g., Lavi & Slone, 2012; Wagner, Cohen & Brook, 1996; Ge et al., 2009). Specific to acculturative stress, findings suggest that parental support (which included components of warmth) protected Latino adolescents from the negative effects of acculturative stress (Crockett et al., 2007). That is, in the presence of low parental support, acculturative stress related to greater depressive and anxiety symptoms; in the presence of high parental support, there was no association.

Among adolescent mothers, studies have suggested that maternal (grandmother) warmth has a direct effect on adolescent mothers’ psychological functioning, which includes depressive symptoms (Barnet, Joffe, Duggan, Wilson, & Repke, 1996; Brown, Harris, Woods, Buman, & Cox, 2012); however, far less work has focused on the moderating role of maternal warmth (e.g., Barnet et al., 1996). The current study examined if warmth experienced in the adolescent mother-grandmother relationship protected adolescent mothers from the expected negative effects of acculturative and enculturative stress on depressive symptoms during the transition to parenthood. Given the important role of grandmothers in Latina adolescent mothers’ lives (Contreras et al., 2002), understanding the protective role of maternal (grandmother) warmth might be especially relevant. Further, for this population, identifying malleable factors such as maternal warmth that can protect individuals from the negative impact of stress is especially necessary in designing interventions for at-risk youth, such as Mexican-origin adolescent mothers.

The Current Study

The current study examined changes in depressive symptoms from the third trimester of pregnancy to three years postpartum among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. Consistent with prior work examining the transition to parenthood in adolescent mothers, we expected a decline in depressive symptoms across the transition to parenthood (Hypothesis 1). Next, we examined the within-person changes in acculturative stress, enculturative stress, and maternal warmth across time. Guided by theories of stress and depression (Hammen 2005), we hypothesized that within-person increases in both acculturative and enculturative stress would relate to increases in adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms (Hypothesis 2a and 2b). Further, we expected that within-person increases in maternal warmth would relate to decreases in depressive symptoms (Hypothesis 3). Finally, we examined the protective role of maternal warmth, hypothesizing that within-person associations between acculturative/enculturative stress and depressive symptoms would be weaker when maternal warmth was high (Hypothesis 4). Given that many adolescent mothers are faced with economic hardship (e.g., Moore & Brooks-Gunn, 2002), and that this hardship relates to psychological functioning (e.g., McLoyd, 1990), we controlled for within-person changes in economic hardship in all analyses. Further, given links between nativity and youths’ depressive symptoms (e.g., Peña et al., 2008) and acculturative/enculturative stress (Rodriquez et al., 2002), we explored the role of adolescent mothers’ nativity in (a) the effects of acculturative and enculturative stress on depressive symptoms, and (b) the protective nature of maternal warmth on this association.

Method

Data for the current study came from four waves of a larger longitudinal project focused on adolescent mothers and their mother figures (e.g., mother, grandmother; Author citation). Adolescents (N = 204) were unmarried, pregnant, Mexican-origin females between the ages of 15 and 18 years old (Mage = 16.80, SD = 1.00) in their third trimester of pregnancy (Mweeks of pregnancy = 30.9, SD = 4.52) at Wave 1 (W1). Adolescents were re-interviewed 10 months (W2), 24 months (W3), and 36 months (W4) postpartum. At W2, 96% of the original adolescent sample was interviewed. At W3 and W4, 85% and 84% of the original adolescent sample was interviewed. Adolescent mothers reported their racial background as White, Hispanic (80%), American Indian or Alaskan native (3%), Black or African American (10%) and Pacific Islander or Asian (2%). Five percent did not report their racial background. In terms of generational status, 36% of adolescent mothers were born in Mexico; 30% were born in the U.S., but had Mexico-born parents and grandparents; 24% were U.S.-born, and had at least one U.S- born parent or grandparent, and 10% were U.S.-born and had no immediate Mexico-born family members. Adolescents’ mother figures included adolescents’ biological mothers (88.2%), grandmothers (2.9%), aunts (2.0%), boyfriends’ mothers (3.4%) and other kin (3.5%).2 A majority of adolescents completed the interview in English at W1 (61.3%), whereas a majority of mother figures completed the interview in Spanish at W1 (69.1%). At the start of the study, most adolescents resided with their mother figures (87%). Across the study, the percentage dropped to 69% (W2), 59% (W3), and 51% (W4). In terms of adolescents’ relationship status, a majority of adolescent mothers reported that they were in a romantic relationship at W1 (71%, n = 145), and this number remained relatively stable across waves (68% at W2, 70% at W3, and 73% at W4). Over half of adolescent mothers were enrolled in high school at W1 (58.3%). Median household income was $22,067 (SD = $19,839) at W1, $19,328 (SD = $18,312) at W2, $19,984 (SD = $18,938) at W3, and $19,000 (SD = $19,545) at W4.

Procedures

Adolescent mothers were recruited from high schools, health centers, and community resource centers in a Southwestern metropolitan area. In-home semi-structured interviews were conducted at all four waves by female interviewers and lasted approximately 2.5 hours. All participants were interviewed in their language of choice (i.e., English or Spanish). At W1, parental consent and youth assent were obtained for participants who were younger than 18 years old, and informed consent was obtained for participants who were 18 years and older. Each participant received $25 for their participation in W1, $30 for W2, $35 for W3, and $40 for W4.

Measures

All measures were translated into Spanish using back-translation with decentering (Erkut, 2010; Knight, Roosa, & Umaña-Taylor, 2009). Specifically, measures were translated into Spanish (target language) and back translated into English (source language) by two separate individuals. Discrepancies between the original source and the back-translated version were discussed by the research team and modifications to both the original and translated versions (i.e., the original English version and the Spanish version) were considered (Erkut, 2010; Knight et al., 2009). A strength of this approach is that it takes into account the idiosyncrasies of both the source and target language by allowing for changes in the original scale (Erkut, 2010). A limitation, however, is that careful attention is needed when decentering to ensure that the revised items are still adequately capturing the construct (Erkut, 2010; Knight et al., 2009).

Depressive symptoms

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) was used to assess depressive symptoms at all four waves. Participants responded to 20 items (e.g., “I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me”) that assessed the frequency of depressive symptoms in the past week. Items were scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day) to 3 (mostly or almost all the time (5–7 days), and responses were summed with higher values indicating more depressive symptoms. Prior work has demonstrated adequate reliability of the CES-D in other Latino samples (McHale, Updegraff, Shanahan, Crouter, & Killoren, 2005), and assessed measurement equivalence across European American and Mexican-origin youth (Crockett, Randall, Shen, Russell, & Driscoll, 2005). For the current study’s sample, the scale demonstrated adequate internal consistency among participants interviewed in English (αEnglish = .87, .89, .92 and .89 for W1, W2, W3, and W4, respectively) and among those interviewed in Spanish (αSpanish = .90, .90, .89 and .92 for W1, W2, W3, and W4, respectively).

Acculturative and enculturative stress

The Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory (MASI; Rodriquez et al., 2002) was used to assess adolescents’ perceptions of acculturative and enculturative stress at W1 through W4. Developed for use with Mexican-origin individuals living in the United States, this measure consists of 25 items that examine four different domains: (a) Spanish competency pressures (e.g., I have a hard time understanding others when they speak Spanish) (b) English competency pressures (e.g., I have a hard time understanding others when they speak in English), (c) Pressure to acculturate (e.g., It bothers me when people don’t respect my Mexican/Latino values), and (d) Pressure against acculturation (e.g., People look down on me if I practice American customs). In line with the broader conceptualization of the MASI, the English competency pressures and pressures to acculturate subscales were combined to represent acculturative stress, whereas the Spanish competency pressures and pressures against acculturation subscales were combined to represent enculturative stress. Participants were asked to indicate whether or not each event occurred within the last 3 months, and how stressful the events were utilizing a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (did not happen) to 5 (extremely stressful). Responses were averaged, with higher scores indicating higher levels of acculturative or enculturative stress. Each scale demonstrated adequate internal consistency among participants interviewed in English (acculturative stress: αEnglish = .89, .84, .86 and .85 for W1, W2, W3, and W4, respectively; enculturative stress: αEnglish = .88, .89, .89 and .86 for W1, W2, W3, and W4, respectively) and among those interviewed in Spanish (acculturative stress: αSpanish = . 79, .81, .75 and .81 for W1, W2, W3, and W4, respectively; enculturative stress: αSpanish = .91, .92, .93 and .93 for W1, W2, W3, and W4, respectively).

Maternal warmth

The Child Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (CRPBI) was used to assess adolescents’ reports of maternal warmth at all waves. Participants responded to 8 items (e.g., “My mother makes me feel better after talking over my worries with her.”) using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The measure has been cross-validated with Latino mothers and adolescents (Knight, Virdin, & Roosa, 1994). In the current study, the scale demonstrated adequate internal consistency among participants interviewed in English (αEnglish = .90, .92, .94 and .93 for W1, W2, W3, and W4, respectively) and in Spanish (αSpanish = .86, .91, .93 and .95 for W1, W2, W3, and W4, respectively).

Economic hardship

The Economic Hardship measure (Barrera, Caples, & Tein, 2001) was used to assess economic distress in adolescents’ families at W1, W2, W3 and W4. Using 18 items, the scale assesses four components of economic hardship in the past 3 months. The Financial Strain subscale consisted of 2 items and asked adolescents to indicate how often in the next 3 months their family is likely to be without food, housing, and basic necessities. Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The Inability to Make Ends Meet (3 items) and the Not Enough Money for Necessities (4 items) subscales assessed the degree to which adolescents and their families have had difficulties making ends meet, and perceptions of their ability to afford necessities, respectively. Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Economic Adjustments or Cutbacks subscale (9 items) asked adolescents to respond to questions about adjustments or cutbacks their family has had to make (e.g., In the last 3 months, has your family had to change food shopping or eating habits to save money?). Adolescents responded either no (0) or yes (1). Scoring guidelines from Barrera et al. (2001) were followed, whereby a composite score was created by standardizing each subscale score, weighting them based on the number of items within each subscale, and creating a mean with the scores. Higher scores reflected greater perceived economic hardship. Reliability estimates across all items at each time point demonstrated adequate internal consistencies among participants interviewed in English (αEnglish = .86, .85, .80 and .86 for W1, W2, W3, and W4, respectively) and in Spanish (αSpanish = .85, .83, .87 and .86 for W1, W2, W3, and W4, respectively).

Results

Analytic Plan

Given our goal of examining intra-individual changes in depressive symptoms across time, we conducted growth models in the multi-level modeling (MLM) framework (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) using PROC MIXED in SAS 9.2. This approach accounts for the nested nature of the data and utilizes maximum likelihood (ML) estimation to handle the patterns of missing data inherent in longitudinal designs (Enders, 2010). Considered one of the “state of the art” missing data techniques, maximum likelihood estimation utilizes the expectation and maximization (EM) algorithm to obtain accurate parameter estimates and standard errors, accounting for missing data patterns (Enders). Maximum likelihood is not an imputation procedure (values are not imputed into the dataset); rather, it uses available data in the sample to identify parameter values that came from the population and accordingly makes adjustments to parameter estimates (Enders). Specific to SAS, the PROC MIXED procedure utilizes maximum likelihood estimation to account for missingness on the dependent variable, but not for missingness on the independent variables (Allison, 2012). Although this is a software limitation, a strength of the growth modeling approach, more broadly, is that it includes each individual in an analysis as long as they have at least one time-point of data. For the current study, 70% of our sample had complete data on the independent variables of interest across all four waves. An additional 14% had complete data across at least three waves, and 10% of participants had complete data across at least two waves. Only 5% of participants had only W1 data. We examined differences on W1 variables and nativity status and found no differences between each of the groups (i.e., 4 waves of data, 3 waves of data, 2 waves of data, and 1 wave of data) for all study variables. Thus, we proceeded with this analytic approach to test our hypotheses. In line with recommendations (Molenberghs & Kenward, 2007), all analyses utilized an unstructured covariance matrix.

First, we examined Mexican-origin adolescent mothers’ trajectories of depressive symptoms (Hypothesis 1). Our MLM growth models were 2-level growth models with occasions nested within individuals. At Level 1, we included wave as our metric of time to describe the changes in depressive symptoms across participation in the study. The time variable was centered at W1 so that the intercept reflected adolescents’ depressive symptoms at the start of the study (i.e., third trimester of pregnancy). Given the range of age at W1, age at first wave was included as a control variable. To examine differences in depressive symptom trajectories by adolescent nativity (coded 0 = Mexico-born, 1 = U.S.-born), we then included nativity (as a main effect) and an interaction between nativity and time.

Next, we examined if fluctuations in acculturative stress and/or enculturative stress and maternal warmth would predict adolescent mothers’ changes in depressive symptoms, controlling for fluctuations in economic hardship (Hypotheses 2a, 2b, & 3). Separate models were examined for each type of stress (i.e., acculturative, enculturative). In these models, time-varying predictors of acculturative/enculturative stress, maternal warmth, and economic hardship were added at Level 1. In line with Hoffman and Stawski (2009), time-varying predictors were group-mean centered (individual’s score minus individual’s cross-time mean) and thus reflect a within-person (WP) effect; specifically, a significant positive WP acculturative/enculturative stress effect would suggest that, on occasions when an adolescent mother reports greater acculturative/enculturative stress than usual (compared to her own cross-time average), she also reports greater levels of depressive symptoms after accounting for fluctuations in economic hardship and maternal support. Similarly, a significant negative WP maternal warmth effect would suggest that, on occasions when an adolescent mother reports greater maternal warmth than usual, she also reports lower levels of depressive symptoms, controlling for economic hardship and acculturative/enculturative stress. To examine nativity differences in the within-person association between acculturative/enculturative stress and depressive symptoms, as well as maternal warmth and depressive symptoms, we then included interactions between nativity and each main effect (e.g., acculturative/enculturative stress X nativity; maternal warmth X nativity).

Finally, to test the moderating role of maternal warmth in the relation between acculturative/enculturative stress and depressive symptoms (Hypothesis 4), an interaction between WP acculturative/enculturative stress and WP maternal warmth was added to the model. Significant interactions were probed by examining the association between WP acculturative/enculturative stress and depressive symptoms at high (1 SD above the mean) and low (1 SD below the mean) levels of WP maternal warmth (Aiken & West, 1991). Again, to understand the role of nativity, we then examined if the interaction between WP acculturative/enculturative stress and WP maternal warmth differed by nativity (i.e., inclusion of a 3-way interaction).

Although not of primary interest, all models that included time-varying predictors also included an additional Level 2 predictor that represented a between-person (BP) effect of the time-varying predictor. The BP predictors were an aggregate of each time-varying predictor (i.e., economic hardship, acculturative stress, enculturative stress, and maternal warmth). The aggregate predictor was created by computing a cross-time mean for each person (e.g., mean of W1 – W4 acculturative stress) and then this mean was grand-mean centered (individual’s cross time mean – overall sample mean). These BP predictor variables capture relations across the entire sample (or between- individuals). For instance, a significant positive BP acculturative stress effect would suggest that, across individuals, higher levels of acculturative stress, on average, were related to higher levels of depressive symptoms, after controlling for economic hardship and maternal warmth.

Sample Descriptive Information and Correlations

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for the overall sample and separated by adolescents’ nativity. Depressive symptoms appeared to decline across time, with no differences by nativity. We also examined the number of adolescents who displayed symptom levels suggestive of major depressive disorder (MDD) at each wave (not presented in Table 1). In line with recommendations (Roberts, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1991) and other samples including Mexican adolescent mothers (Lara et al., 2012), a CES-D score of 24 or higher was used as the cut-off. At W1, W2, W3 and W4, 27%, 30%, 24%, and 22% of adolescent mothers met the suggested MDD CES-D diagnosis levels, respectively. There were no differences by adolescent mothers’ nativity. In terms of cultural adaptation stress, Mexico-born adolescent mothers reported greater acculturative stress than U.S.-born adolescent mothers (with the exception of W4), whereas U.S.-born adolescent mothers reported greater enculturative stress than Mexico-born adolescent mothers (Table 1). Mexico-born adolescent mothers reported greater economic hardship at W2, W3, and W4, compared to U.S.-born adolescent mothers. Table 2 presents bivariate correlations for all study variables.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Ranges for Study Variables.

| Overall Sample Mean (SD) |

Overall Sample Range |

Mexico-born Mean (SD) |

U.S-born Mean (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive Symptoms | ||||

| Time 1 | 17.98 (10.17) | 1.00 – 54.00 | 18.17 (11.37) | 17.88 (09.50) |

| Time 2 | 17.29 (11.11) | 0.00 – 47.00 | 18.11 (11.63) | 16.79 (10.80) |

| Time 3 | 16.38 (11.36) | 0.00 – 48.00 | 16.95 (10.97) | 16.07 (11.61) |

| Time 4 | 15.02 (10.71) | 0.00 – 58.00 | 15.47 (11.36) | 14.77 (10.38) |

| Acculturative Stress | ||||

| Time 1± | 0.68 (0.73) | 0.00 – 4.79 | 0.91 (0.85) | 0.56 (0.61) |

| Time 2± | 0.65 (0.73) | 0.00 – 3.86 | 0.88 (0.95) | 0.53 (0.56) |

| Time 3± | 0.58 (0.72) | 0.00 – 4.64 | 0.86 (0.93) | 0.45 (0.55) |

| Time 4 | 0.54 (0.63) | 0.00 – 3.86 | 0.63 (0.78) | 0.50 (0.54) |

| Enculturative Stress | ||||

| Time 1± | 0.56 (0.69) | 0.00 – 4.91 | 0.24 (0.37) | 0.73 (0.76) |

| Time 2± | 0.66 (0.74) | 0.00 – 3.55 | 0.32 (0.42) | 0.84 (0.81) |

| Time 3± | 0.65 (0.73) | 0.00 – 3.73 | 0.33 (0.41) | 0.81 (0.80) |

| Time 4± | 0.54 (0.64) | 0.00 – 3.36 | 0.23 (0.35) | 0.69 (0.70) |

| Maternal Warmth | ||||

| Time 1 | 4.04 (0.77) | 1.13 – 5.00 | 4.03 (0.70) | 4.05 (0.81) |

| Time 2 | 3.78 (0.92) | 1.13 – 5.00 | 3.87 (0.90) | 3.72 (0.94) |

| Time 3 | 3.67 (1.01) | 1.00 – 5.00 | 3.70 (1.02) | 3.66 (1.01) |

| Time 4 | 3.82 (0.95) | 1.00 – 5.00 | 3.85 (0.95) | 3.81 (0.95) |

| Economic Hardship | ||||

| Time 1 | −0.02 (2.51) | −4.61 – 8.49 | 0.10 (2.54) | −0.09 (2.50) |

| Time 2± | 0.00 (2.38) | −4.81 – 6.98 | 0.64 (2.37) | −0.37 (2.32) |

| Time 3± | −0.02 (2.35) | −4.46 – 7.52 | 0.64 (2.55) | −0.36 (2.18) |

| Time 4± | 0.00 (2.39) | −4.41 – 7.25 | 0.59 (2.55) | −0.33 (2.23) |

Note. ± Significant mean-level differences between Mexico-born and U.S.-born participants, p < .05. Economic hardship means reflect a standardized mean-score across the sample. Depressive symptoms reflect sum-scores of the CES-D.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations among study variables.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13 | 14. | 15. | 16. | 17. | 18 | 19. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Dep W1 | -- | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Dep W2 | .53 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Dep W3 | .43 | .49 | |||||||||||||||||

| 4. Dep W4 | .51 | .44 | .50 | ||||||||||||||||

| 5. AS Stress W1 | .41 | .32 | .25 | .27 | |||||||||||||||

| 6. Acc Stress W2 | .34 | .29 | .23 | .17 | .68 | ||||||||||||||

| 7. Acc stress W3 | .28 | .14 | .15 | .26 | .50 | .61 | |||||||||||||

| 8. Acc stress W4 | .31 | .20 | .20 | .33 | .47 | .61 | .78 | ||||||||||||

| 9. Enc stress W1 | .23 | .22 | .24 | .09 | .23 | .06 | −.12 | −.11 | |||||||||||

| 10. Enc stress W2 | .18 | .23 | .19 | .07 | .09 | .26 | .01 | .05 | .68 | ||||||||||

| 11. Enc stress W3 | .12 | .14 | .21 | .00 | −.08 | −.01 | .09 | .04 | .56 | .72 | |||||||||

| 12. Enc stress W4 | .05 | .01 | .06 | .03 | −.06 | −.00 | −.03 | .17 | .49 | .54 | .66 | ||||||||

| 13. Warmth W1 | −.27 | −.13 | −.25 | −.10 | .01 | .11 | .05 | −.07 | .03 | .01 | .04 | −.03 | |||||||

| 14. Warmth W2 | −.20 | −.29 | −.19 | −.05 | −.04 | −.04 | −.03 | −.19 | .05 | −.04 | −.00 | −.03 | .53 | ||||||

| 15. Warmth W3 | −.24 | −.15 | −.22 | −.13 | − .01 | −.00 | −.08 | −.16 | .02 | −.06 | −.13 | .01 | .47 | .63 | |||||

| 16. Warmth W4 | −.28 | −.15 | −.20 | −.18 | − .10 | −.13 | −.18 | −.34 | .09 | −.01 | −.00 | −.05 | .47 | .61 | .68 | ||||

| 17. EH W1 | .40 | .20 | .27 | .34 | .27 | .28 | .25 | .31 | .09 | .11 | .02 | .03 | − .09 | −.09 | −.19 | −.23 | |||

| 18. EH W2 | .39 | .31 | .22 | .24 | .31 | .41 | .34 | .38 | .03 | .07 | .01 | .03 | − .10 | −.17 | −.01 | −.22 | .45 | ||

| 19. EH W3 | .34 | .28 | .26 | .29 | .33 | .44 | .40 | .49 | −.03 | .09 | .06 | .08 | − .14 | −.10 | −.14 | −.21 | .41 | .61 | |

| 20. EH W4 | .30 | .30 | .23 | .41 | .25 | .22 | .26 | .31 | −.09 | .03 | −.03 | .05 | − .09 | −.02 | −.03 | −.14 | .42 | .53 | .61 |

Note. For correlations, sample size varied from 147 to 204 due to missing data. For all MLM analyses, however, maximum likelihood estimation was used and included the full sample (N = 204). Dep = depressive symptoms; Acc stress = Acculturative stress; Enc stress = Enculturative stress; Warmth = Maternal warmth; EH = Economic hardship; W1 – W4 = Wave 1 – Wave 4; Correlations higher than .14 p < .05, higher than .19 p < .01, and higher than .26 p < .001.

Depressive Symptom Trajectories of Mexican-origin Adolescent Mothers

An initial growth model was estimated to examine the trajectory of depressive symptoms. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, results revealed that adolescent mothers had moderate levels of depressive symptoms at W1 (b00 = 18.02 (Standard error (SE) = 0.69, p < .001) and that symptoms declined across the four waves (b10 = −.96, SE = .26, p < .001). A quadratic term (time2) was examined but was not significant. We also examined if adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms trajectories differed by nativity. Results revealed no differences at W1 (the intercept) or differences in the decline across time, suggesting similar trajectories among U.S-born and Mexico-born adolescent mothers.

Acculturative Stress and Maternal Warmth

Next, we examined how within-person fluctuations in acculturative stress and maternal warmth related to adolescents’ depressive symptoms, controlling for fluctuations in economic hardship (Table 3, Model 1). Consistent with Hypothesis 2a and 3, results revealed a significant WP acculturative stress and maternal warmth effect, accounting for WP economic hardship. Specifically, on occasions when an adolescent mother reported greater acculturative stress (compared to her own cross-time average), she reported higher depressive symptoms. For maternal warmth, on occasions when an adolescent mother reported greater maternal warmth (compared to her own cross-time average), she reported lower depressive symptoms. WP economic hardship emerged as a significant control, suggesting that within-person fluctuations in economic hardship related to depressive symptoms in the expected direction. Significant BP effects emerged for acculturative stress, maternal warmth, and economic hardship stress suggesting that, on average, adolescent mothers who reported greater economic hardship and acculturative stress and lower maternal warmth, tended to report greater depressive symptoms. Next, we examined if the relations between the WP predictors (i.e., acculturative stress and maternal warmth) and depressive symptoms differed by adolescent nativity (Table 3, Model 2). Results revealed no differences, suggesting that fluctuations in acculturative stress and maternal warmth related to depressive symptoms in a similar way for U.S.-born and Mexico-born adolescent mothers.

Table 3.

MLM Growth models of depressive symptoms with acculturative stress, maternal warmth, and economic hardship (N = 204)

| Predictors | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 17.07 (0.90)*** | 17.00 (0.90)*** | 17.08 (0.90)*** | 17.00 (0.90)*** |

| Nativity | 1.79 (1.07) | 1.87 (1.08) | 1.73 (1.08) | 1.65 (1.08) |

| Age at W1 | 0.28 (0.50) | 0.26(0.50) | 0.30 (0.49) | 0.35 (0.50) |

| Time | −0.98 (0.27)*** | −0.97 (0.27)*** | −0.98 (0.27)*** | −0.93 (0.26)*** |

| Acculturative stress (AS) (WP) | 1.97 (0.79)* | 3.05 (1.21)* | 1.99 (0.79)* | 3.17 (1.20)* |

| Maternal warmth (MW) (WP) | −1.45 (0.55)** | −0.64 (0.93) | −1.42 (0.56)* | −0.87 (0.93) |

| Economic hardship (WP) | 0.70 (0.20)*** | 0.68 (0.19)*** | 0.70 (0.20)*** | 0.65 (0.19)*** |

| AS X Nativity | −1.97 (1.58) | −1.79 (1.56) | ||

| MW X Nativity | −1.31 (1.15) | −0.98 (1.15) | ||

| AS (WP) X MS (WP) | −1.46 (1.68) | 3.50 (2.33) | ||

| AS X MW X Nativity | −10.39 (3.38)** | |||

| Acculturative stress (BP) | 3.32 (0.91)*** | 3.35 (0.91)*** | 3.29 (0.91)*** | 3.13 (0.91)*** |

| Maternal warmth (BP) | −2.72 (0.68)*** | −2.68 (0.68)*** | −2.76 (0.68)*** | −2.61 (0.68)*** |

| Economic hardship (BP) | 1.67 (0.29)*** | 1.68 (0.29)*** | 1.67 (0.29)*** | 1.65 (0.29)*** |

Note. Unstandardized coefficients are presented. Nativity is coded 0 = Mexico, 1 = U.S. W1 = Wave 1; WP = Within-person predictor; BP = Between-person predictor.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

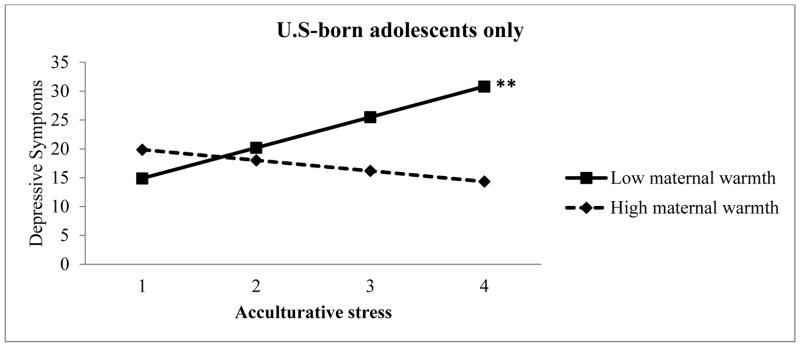

We then examined if the relation between WP acculturative stress and depressive symptoms was moderated by WP maternal warmth (Hypothesis 4). As seen in Model 3 (Table 3) an interaction between WP maternal warmth and WP acculturative stress was added and was not significant. To examine if the protective effect of maternal warmth in the relation between acculturative stress and depressive symptoms might differ based on adolescents’ nativity, we then tested a three-way interaction (acculturative stress X maternal warmth X nativity). The interaction was significant and was probed by running a model separately by nativity. Results revealed only partial support for Hypothesis 4, suggesting that a protective effect was evident for U.S.-born adolescent mothers (b = −6.71 (SE = 2.38), p < .01), but not for Mexico-born adolescent mothers (b = 2.50 (SE = 2.22), p = .26). Specifically, among U.S-born participants, at high levels of WP maternal warmth (1 SD above the mean), no relation emerged between WP acculturative stress and depressive symptoms (b = −1.84 (SE = 1.54) p = .23). At low levels of WP maternal warmth (1 SD below the mean), however, a significant positive relation emerged between WP acculturative stress and depressive symptoms (b = 5.31, SE = 1.67, p < .01). Figure 1 illustrates this association.

Figure 1.

The within-person relation between acculturative stress and depressive symptoms at low and high levels of maternal warmth for U.S.-born adolescent mothers. **Slope is significant p < .01.

Enculturative Stress and Maternal Warmth

Next, we examined the role of within-person fluctuations in enculturative stress and the relation to adolescents’ depressive symptoms (Hypothesis 2b), controlling for fluctuations in economic hardship (Table 4, Model 1). Consistent with our hypothesis, results revealed a significant WP enculturative stress effect; on occasions when an adolescent mother reported greater enculturative stress (compared to her own cross-time average), she reported higher depressive symptoms. Similar to acculturative stress models, WP maternal warmth emerged as significant in the expected direction. Significant BP effects emerged for enculturative stress suggesting that, on average, adolescent mothers who reported greater enculturative stress, tended to report greater depressive symptoms. Significant BP maternal warmth and economic hardship effects emerged in the expected direction. Next, we examined if the relations between the WP predictors (i.e., enculturative stress and maternal warmth) and depressive symptoms differed by adolescent nativity (Table 4, Model 2). No differences emerged.

Table 4.

MLM Growth models of depressive symptoms with enculturative stress, maternal warmth, and economic hardship (N = 204)

| Predictors | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 18.61 (0.95)*** | 18.59 (0.95)*** | 18.50 (0.94)*** | 18.50 (0.95)*** |

| Nativity | −0.46 (1.16) | −0.41 (1.16) | −0.49 (1.15) | −0.45 (1.15) |

| Age at W1 | 0.37 (0.50) | 0.36 (0.50) | 0.39 (0.49) | 0.37 (0.49) |

| Time | −1.07 (0.27)*** | −1.07 (0.27)** | −1.04 (0.27)*** | −1.05 (0.27)*** |

| Enculturative stress (ES) (WP) | 1.87 (0.80)* | 4.25 (1.90)* | 1.86 (0.80)* | 3.90 (1.98)* |

| Maternal warmth (MW) (WP) | −1.36 (0.56)* | −0.49 (0.93) | −1.43 (0.56)* | −0.49 (0.93) |

| Economic hardship (WP) | 0.69 (0.20)*** | 0.69 (0.20)*** | 0.73 (0.20)*** | 0.73 (0.20)*** |

| ES X Nativity | −2.99 (2.10) | −2.56 (2.16) | ||

| MW X Nativity | −1.35 (1.15) | −1. 47 (1.16) | ||

| ES (WP) X MS (WP) | −3.91 (1.78)* | −2.85 (4.71) | ||

| ES X MW X Nativity | −1.06 (5.07) | |||

| Enculturative stress (BP) | 2.76 (0.90)** | 2.76 (0.90)** | 2.63 (0.89)** | 2.63 (0.89)** |

| Maternal warmth (BP) | −2.82 (0.68)*** | −2.80 (0.68)*** | −2.68 (0.68)*** | −2.66 (0.68)*** |

| Economic hardship (BP) | 1.98 (0.27)*** | 1.99 (0.27)*** | 2.00 (0.27)*** | 2.00 (0.27)*** |

Note. Unstandardized coefficients are presented. Nativity is coded 0 = Mexico, 1 = U.S. W1 = Wave 1; WP = Within-person predictor; BP = Between-person predictor.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

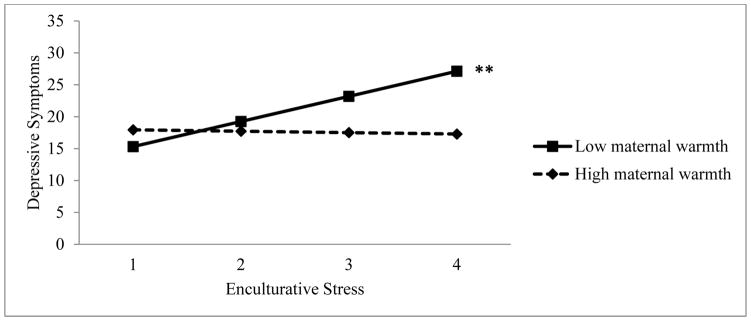

We then examined if the relation between WP enculturative stress and depressive symptoms was moderated by WP maternal warmth. As seen in Model 3 (Table 4) an interaction between WP maternal warmth and WP acculturative stress was added and emerged as significant. In line with Hypothesis 4, probing of this interaction revealed that at high levels of WP maternal warmth, no association emerged between WP enculturative stress and depressive symptoms (b = − .22 (SE = 1.25), p = .86, see Figure 2). In the context of low levels of WP maternal warmth, there was a positive association between WP enculturative stress and depressive symptoms (b = 3.94 (1.24), p < .01). The three-way interaction between enculturative stress, maternal warmth, and nativity was examined and emerged as non-significant (Table 4, Model 4), suggesting that the protective effect was not different for U.S-born and Mexico-born adolescent mothers.

Figure 2.

The within-person relation between enculturative stress and depressive symptoms at low and high levels of maternal warmth for the full sample of adolescent mothers. **Slope is significant p < .01.

Discussion

Latinas have the highest teenage birth rate in the U.S. (National Vital Statistics Report, 2012), but little empirical work has examined the psychological functioning of Latina adolescent mothers during the transition to parenthood and the risk and protective processes at play during this time. The current study addressed these limitations by examining trajectories of depressive symptoms in Mexican-origin adolescent mothers from their third trimester of pregnancy to 36 months postpartum, and investigating the effects of two unique aspects of stress that emerge during the cultural adaptation process, acculturative and enculturative stress (Berry, 2003; Gonzales, et al., 2013). Further, guided by a risk and resilience framework (Masten, Best, & Garmezy, 1990) and models of stress and coping (Cohen et al., 2000; Cohen & Willis, 1985), we examined maternal warmth as an important asset to adolescent mothers, relating to lower levels of depressive symptoms, and as a protective factor, diminishing the effect of acculturative/enculturative stress on depressive symptoms. With longitudinal data, we used a robust within-person design, allowing for the examination of how adolescent mothers’ own fluctuations in stress and warmth (compared to their average level of stress and warmth) played out across the transition to parenthood. Our findings suggest that Mexican-origin adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms declined during the transition to parenthood, and within-person increases in acculturative stressors and enculturative stressors related to increases in depressive symptoms. Maternal warmth emerged as an important asset for all adolescent mothers, and interacted with enculturative stress to buffer the effects of stress on depressive symptoms. For acculturative stress, however, maternal warmth only emerged as protective for U.S. born adolescent mothers. Our study provides valuable descriptive information about the psychological adjustment of adolescent mothers within an ethnic group that makes up one of the largest and fastest growing ethnic minority populations in the U.S. (Passel, Cohn, & Lopez, 2011), and underscores the importance of examining both the challenges associated with dual-cultural adaptation and the protective role of familial relationships within this high risk sample.

Depressive Symptoms Trajectories in Mexican-Origin Adolescent Mothers

Although prior work has demonstrated prevalence or mean-level differences in depressive symptoms among adolescent mothers, their non-pregnant counterparts, and adult mothers (Lanzi et al., 2009; Mollborn & Morningstar, 2009), less work has focused on the intra-individual changes in adolescent mothers’ symptoms during the transition to parenthood, and even less is known specifically about Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. Our findings suggest that, on average, Mexican-origin adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms decline from the third trimester of pregnancy to about 36 months postpartum. This decline in symptoms is consistent with our hypothesis, and in line with the findings among adult women transitioning into parenthood (e.g., Beeghly et al., 2002), other samples of adolescent mothers (Brown et al., 2012; Leadbeater et al., 1990; Schmidt et al., 2006), and normative age-related trends in Mexican-origin adolescent females (Author citation). Although the exact mechanisms underlying the decline in symptoms after childbirth are unknown, scholars have posited that mothers, adult and adolescent, might be vulnerable to depression during pregnancy due to prenatal and delivery concerns, but adjust after the baby is born (Ritter et al., 2000). Physiological explanations focus on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (Heron et al., 2004); specifically, increased cortisol levels, which have been linked to depressive disorders (Burke, Davis, Otte, & Mohr, 2005), are nearly twice as high during pregnancy, but substantially lower after delivery (Allolio, Hoffmann, Linton, Winkelmann, Kusche, & Schulte, 1990). For the current study, a similar process appears to be happening, suggesting that despite limited economic resources and juggling the challenges associated with the transition to parenthood during adolescence, Mexican-origin adolescent mothers, like other mothers and their nulliparous adolescent counterparts, are adapting to the challenges presented.

In terms of overall levels of depressive symptoms in the current study, our sample’s mean for depressive symptoms appears higher than those of other samples of Latina and Mexican-origin adolescents who were not pregnant or parenting (e.g., Author citations), but appears either similar (i.e., Ginsburg et al., 2008; Thompson & Walker, 2004) or lower when compared to the means reported in studies focused on adolescent mothers (e.g., Brown et al., 2012; Caldwell, Antonucci, Jackson, Wolford, & Osofsky, 1997) 3. Together, our findings provide important data about depressive symptoms among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers and, furthermore, suggest that these young mothers are at similar or possibly lower risk for displaying elevated depressive symptoms as adolescent mothers from other ethnic and racial backgrounds.

Cultural Adaptation Stress and Depressive Symptoms

Turning to the stressors that may inform Mexican-origin adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms, we examined the relation between stress associated with dual-cultural adaptation and mothers’ depressive symptoms, while also taking into account youths’ economic hardships. Cultural adaptation is considered a dynamic process involving adapting to the mainstream culture (acculturation), while maintaining or adapting to one’s own culture of origin (enculturation; Berry, 2003; Gonzales, et al., 2012). Stress can emerge from both processes and is theorized to be important in individuals’ mental health (Berry; Gonzales, et al.; Rodriguez et al., 2002). Our empirical understanding, however, has primarily focused on aspects of acculturative stress, leaving us with limited knowledge of the effects of enculturative stress, especially longitudinally. Understanding both aspects of stress provides us with a more complete picture of the stress processes at work during the dual-cultural adaptation process.

Consistent with the study’s hypothesis, acculturative and enculturative stressors emerged as important predictors of adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms. Specifically, the findings suggested that, on average, acculturative and enculturative stress were positively related to adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms (BP effect) and, more importantly, fluctuations in these stressors related to increases in their depressive symptoms for both U.S-born and Mexico-born adolescent mothers (WP effects), above and beyond the effects of economic hardship. Given that the study used a within-person analytic approach, the findings reveal a within-person process; individuals’ increases in acculturative and enculturative stress were in relation to their own average acculturative and enculturative stress level. Indeed, theories of stress and depression suggest that within-person processes play an important role in the development of depressive disorders and symptoms (Hankin, 2012; Hankin & Abela, 2005). By using a within-person design, we not only empirically tested this theoretical notion, but we control for biases of unobserved stable characteristics of the adolescent mother, family, or environment (Dearing & Taylor, 2007; Singer & Willet, 2003). Together, our findings complement theoretical work suggesting that both aspects of the dual-cultural adaptation process can be stressful to adolescents and are important when understanding their psychological well-being (Berry, 1993; Gonzales et al., 2012).

Protective Role of Maternal Warmth

In addition to understanding the role of dual-cultural adaptation stressors, the current study examined maternal warmth as an asset (main effect) and protective factor (interactive effect). Familial relationships are theorized to be an important protective resource of individuals facing stress (Cohen & Wills, 1985); however little work has examined these protective processes in adolescent mothers longitudinally. Such an examination is critical in furthering our understanding of resilience in high risk samples and identifying targetable factors for intervention. Similar to our approach with acculturative stress, the current study examined within-person processes of maternal warmth, as both a predictor of depressive symptoms and as a moderator of the association between acculturative/enculturative stress and symptoms. Across all models, results revealed that maternal warmth was directly related to fluctuations in depressive symptoms; adolescent mothers, both U.S.-born and Mexico-born, reported greater depressive symptoms on occasions when they reported lower maternal warmth. In terms of the interactions with acculturative stress, results revealed that maternal warmth was only protective for U.S.-born youth. Specifically, acculturative stress and depressive symptoms were unrelated when U.S.-born adolescent mothers simultaneously reported high maternal warmth (compared to their own overall average). When U.S. born adolescent mothers reported low levels of maternal warmth, increases in acculturative stress were related to increases in depressive symptoms. This finding suggests a protective effect of maternal warmth for U.S.-born youth and may reflect the benefits of mothers’ (grandmothers’) sensitivity in responding to adolescents’ stressful environment. That is, when mothers (grandmothers) were sensitive to the stress that their adolescent was experiencing by being warmer and more accepting, the benefits were noted by adolescents’ endorsement of fewer depressive symptoms.

Interestingly, this same protective effect did not emerge for Mexico-born adolescent mothers. One explanation could be related to the levels of acculturative stress that Mexico-born youth face. As compared to their U.S-born counterparts, these youth experienced significantly greater levels. Although maternal warmth might be similarly experienced for both groups of youth (no mean-level differences), its buffering effect is only felt among U.S.-born youth, who are, on average, experiencing lower levels of acculturative stress. Among Mexico-born youth, the experience of maternal warmth might be unable to protect them, given that they are experiencing a higher level of stress. Indeed, a noted limitation of within-person analyses is the exclusive focus on fluctuations in stress within an individual, without attention to the absolute levels of stress being experienced; thus, a fluctuation from .5 to 1 is treated similar to a fluctuation from 2.0 to 2.5 (Abela & Hankin, 2009). For Mexico-born youth, the higher absolute level could be playing a role.

Finally, maternal warmth emerged as a significant moderator in the association between enculturative stress and depressive symptoms among U.S-born and Mexico-born adolescent mothers. Specifically, when an increase in enculturative stress was accompanied by an increase in maternal warmth, there was no change in adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms. However, if an increase in enculturative stress was accompanied by a decrease in maternal warmth, an increase in depressive symptoms was evident. This finding suggests that, among adolescent mothers, the impact of enculturative stress might be particularly responsive to the quality of family relations. Given that enculturative stress is more likely to emerge from within the family context and center around family expectations to engage in the heritage culture (e.g., pressures to speak Spanish, pressures to maintain the heritage cultural values), the presence of maternal acceptance and warmth during such an experience could be particularly important. Put differently, adolescents’ experiences with enculturative stress in the context of increased feelings of acceptance and warmth from a key family member (i.e., their mother) may not result in decreased mental health; whereas experiences of enculturative stress accompanied by perceived decreases in maternal warmth may place adolescent mothers at greater risk for increases in depressive symptoms.

Limitations and Future Directions

In sum, the current study provides important descriptive information and contributes to our understanding of Mexican-origin adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms during the first three years of their young children’s lives. Our findings suggest that stressors associated with the acculturation and enculturation process play a detrimental role in adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms, with relationships with grandmothers providing important opportunities for resilience. In line with the risk and resilience perspective (Masten, Best, & Garmezy, 1990), our findings are promising as they suggest that even small fluctuations in maternal warmth are important among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. From a preventive science perspective, the adolescent-mother relationship could be a malleable factor important in program development among this population.

Despite these contributions, there are several limitations worth noting. First, although within-person analyses control for the influence of stable individual or contextual factors, they can be biased by omitted time-varying factors (Singer & Willet, 2003). Given that prior work has suggested that economic hardship plays an important role in adolescent mothers’ lives (Moore & Brooks-Gunn, 2002) and in adolescents’ psychological outcomes (e.g., Dearing, McCartney, & Taylor, 2006; McLoyd, 1998), the current study controlled for fluctuations in adolescent mothers’ economic hardship. The effects of cultural adaptation stressors, namely acculturative stress, emerged above and beyond these effects. However, as theories of stress would suggest (Pearlin, 1999; Pearlin, Menaghan, Lieberman, & Mullan, 1981), stressors are not experienced in isolation and stressors related to a particular area (e.g., cultural adaptation) can further increase the likelihood of encountering stressors in other domains (e.g., peer conflict; Pearlin, 1999). Thus, the current study’s findings do not suggest that dual-cultural adaptation stress is the only contributor to adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms, but rather that this serves as an important within-person predictor of adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms.

An additional limitation is that the current study did not examine the interplay between acculturative and enculturative stress, given model complexities and limitations of statistical power. Theoretical models of cultural adaptation posit that the processes of acculturation and enculturation happen simultaneously; thus, an individual could be experiencing both aspects of stress in a dynamic way (Gonzales et al., 2012). Related, the current study relied upon adolescents’ birth place as an indicator of generational differences in experiencing stressors associated with cultural adaptation. Given the study’s sample size, we were unable to draw comparisons across specific generational statuses (e.g., differences between 1st generation versus 2nd generation; 1st generation versus 3rd generation) in the association between stressors and depressive symptoms. Future work with larger samples and greater representation of each generational status could explore the shifts that occur in experiences of stressors across each status and, further, if the role of cultural adaptation stressors and maternal warmth differs as a function of generation status.

An additional consideration in the current within-person analysis pertains to the issue of reciprocal causation. Although theory would suggest that stress predicts depressive symptoms (Hammen, 2005), and numerous longitudinal studies would support theory (e.g., Ge et al., 2001; Goodyer, Herbert, Tamplin, & Altham, 2000), the current analysis does not address issues of causation, as only the contemporaneous associations between stress and depressive symptoms were assessed.. That is, we cannot be sure that acculturative or enculturative stress led to greater depressive symptoms. An alternative explanation could be that increased depressive symptoms predicted greater perceptions of stress. Indeed, the stress-generation hypothesis (Hammen, 1991) suggests that depression can contribute to the perception of subsequent experiences as more stressful. A proposition of this theory, however, is that stress-generation is predicted by individual characteristics (e.g., cognitive style, attachment style; Hammen, 2006). That is, certain individuals who possess a particular cognitive or attachment style are vulnerable to the depression-stress direction of effects. To the extent to which these individual characteristics are stable, the current study’s focus on within-person effects strengthens our confidence that the stress-generation effect is not what is being captured. Nevertheless, longitudinal examinations of cultural adaptation stress and depressive symptoms, with the consideration of cognitive and attachment styles, are needed to further our understanding of the bi-directional associations between acculturative and enculturative stress and Mexican-origin adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms.

Finally, the current study utilized adolescent mothers’ self-report for all constructs considered. The reliance on self-report data can inflate observed associations and is prone to issues of shared method variance. Future studies would benefit from utilizing multi-informant methods that could provide a stronger test of the relations observed in our study.

In closing, this study provides one of the first examinations of the relations between acculturative and enculturative stress, maternal warmth, and depressive symptoms among adolescent mothers using longitudinal data. The study highlights the changes in psychological adjustment experienced while Mexican-origin adolescent mothers transitioned to parenthood, and contributes to our understanding of the bi-dimensional stress process of cultural adaptation. Stressors tied to the acculturative and enculturative process are important challenges for Mexican-origin adolescent mothers, but the effects of these stressors appear to depend largely upon the supportive nature of the family context.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funds from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD061376; PI: Umaña-Taylor), the Department of Health and Human Services (APRPA006011; PI: Umaña-Taylor), and the Cowden Fund and Challenged Child Project of the School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University. We thank the adolescents and female family members who participated in this study. We also thank Edna Alfaro, Mayra Bámaca, Diamond Bravo, Emily Cansler, Lluliana Flores, Melinda Gonzales-Backen, Elizabeth Harvey, Melissa Herzog, Sarah Killoren, Ethelyn Lara, Esther Ontiveros, Jacqueline Pflieger, Alicia Godinez and the undergraduate research assistants of the Supporting MAMI project for their contributions to the larger study.

Footnotes

These studies use the term acculturative stress to refer to stressors associated with both the acculturation and enculturation process.

Adolescents nominated their mother figures at W1. Differences by adolescent nativity status on mother figure nominations were examined and indicated that U.S.-born and Mexico-born adolescents were similar in their nominations of biological and non-biological mother figures.

Comparisons were drawn to prior studies that assessed females’ depressive symptoms using the CES-D and within the age range of the current study.

References

- Abela JRZ, Hankin BL. Cognitive vulnerabilities to depression in adolescents: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In: Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt LM, editors. Handbook of depression in adolescents. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis Group; 2009. pp. 335–363. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. SAS global Forum: Statistics and Data analysis. 2012. Handling missing data by maximum likelihood. [Google Scholar]

- Allolio B, Hoffmann J, Linton EA, Winkelmann W, Kusche M, Schulte HM. Diurnal salivary cortisol patterns during pregnancy and after delivery: Relationship to plasma corticotrophin-releasing-hormone. Clinical Endocrinology. 1990;33:279–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1990.tb00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnet B, Joffe A, Duggan AK, Wilson MD, Repke JT. Depressive symptoms, stress, and social support in pregnant and postpartum adolescents. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150:64–69. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170260068011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Caples H, Tein JY. The psychological sense of economic hardship: Measurement models, validity, and cross-ethnic equivalence for urban families. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:493– 517. doi: 10.1023/a:1010328115110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeghly M, Weinberg MK, Olson KL, Kernan H, Riley J, Tronick EZ. Stability and change in level of maternal depressive symptomatology during the first postpartum year. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2002;71:169–180. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00409-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In: Chun KM, Organista PB, Marin G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement and applied research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Birkland R, Thompson K, Phares V. Adolescent motherhood and postpartum depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:292– 300. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3402_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, Harris SK, Woods ER, Buman MP, Cox JE. Longitudinal study of depressive symptoms and social support in adolescent mothers. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2012;16:894– 901. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0814-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan RL, Smokowski PR. Pathways from acculturation stress to substance use among Latino adolescents. Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44:740–762. doi: 10.1080/10826080802544216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke HM, Davis MC, Otte C, Mohr DC. Depression and cortisol responses to psychological stress: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:846–859. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CH, Antonucci TC, Jackson JS, Wolford ML, Osofsky JD. Perceptions of parental support and depressive symptomatology among Black and White adolescent mothers. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 1997;5:173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy B, Zoccolillo M, Hughs S. Psychopathology in adolescent mothers and its effect on mother-infant interactions: A pilot study. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;41:379–384. doi: 10.1177/070674379604100609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Domenech Rodríguez M. Latino families: Myths and realities. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States. Westport, CT: Praeger Press; 2002. pp. 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Gotlieb BH, Underwood LG. Social relationships and health. In: Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottlieb BH, editors. Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists. New York, NY: Oxford; 2000. pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras JM, López IR, Rivera-Mosquera ET, Raymond-Smith L, Rothstein K. Social support and adjustment among Puerto Rican adolescent mothers: The moderating effects of acculturation. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13:228–243. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras JM, Narang D, Ikhlas M, Teichman J. A conceptual model of determinants of parenting among Latin adolescent mothers. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States. Westport, CT: Praeger Press; 2002. pp. 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cox CB, Brooks LR, Valcarcel C. Culture and caregiving: A study of Latino grandparents. In: Cox CB, editor. To grandmothers house we go and stay: Perspectives on custodial grandparents. New York, NY: Springer; 2000. pp. 218–232. [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Iturbide MI, Stone RAT, McGinley M, Raffaelli M, Carlo G. Acculturative stress, social support, and coping: Relations to psychological adjustment among Mexican American college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:347–355. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Randall BA, Shen Y, Russell ST, Driscoll AK. Measurement equivalence of the Center for Epidemiological Studies depression scale for Latino and Anglo adolescents: A national study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:47–58. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:583–619. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing E, Taylor BA. Home improvements: Within-family associations between income and the quality of children’s home environments. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2007;28:427–444. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing E, McCartney K, Taylor BA. Within-child associations between family income and externalizing and internalizing problems. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:237–252. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deal LW, Holt VL. Young maternal age and depressive symptoms: Results from the 1988 National Maternal and Infant Health Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:266–270. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.2.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkut S. Developing multiple language versions of instruments for intercultural research. Child Development Perspectives. 2010;4:19–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Field T. Infants of depressed mothers. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:49–66. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]