Abstract

Context

Some veterans are eligible to enroll simultaneously in a Medicare Advantage (MA) plan and the Veterans Affairs health care system (VA). This scenario produces the potential for redundant federal spending because MA plans would receive payments to insure veterans who receive care from the VA, another taxpayer-funded health plan.

Objective

To quantify the prevalence of dual enrollment in VA and MA, the concurrent use of health services in each setting, and the estimated costs of VA care provided to MA enrollees.

Design

Retrospective analysis of 1 245 657 veterans simultaneously enrolled in the VA and an MA plan between 2004–2009.

Main Outcome Measures

Use of health services and inflation-adjusted estimated VA health care costs.

Results

Among individuals who were eligible to enroll in the VA and in an MA plan, the number of persons dually enrolled increased from 485 651 in 2004 to 924 792 in 2009. In 2009, 8.3% of the MA population was enrolled in the VA and 5.0% of MA beneficiaries were VA users. The estimated VA health care costs for MA enrollees totaled $13.0 billion over 6 years, increasing from $1.3 billion in 2004 to $3.2 billion in 2009. Among dual enrollees, 10% exclusively used the VA for outpatient and acute inpatient services, 35% exclusively used the MA plan, 50% used both the VA and MA, and 4% received no services during the calendar year. The VA financed 44% of all outpatient visits (n=21 353 841), 15% of all acute medical and surgical admissions (n=177 663), and 18% of all acute medical and surgical inpatient days (n=1 106 284) for this dually enrolled population. In 2009, the VA billed private insurers $52.3 million to reimburse care provided to MA enrollees and collected $9.4 million (18% of the billed amount; 0.3% of the total cost of care).

Conclusions

The federal government spends a substantial and increasing amount of potentially duplicative funds in 2 separate managed care programs for the care of same individuals.

In the united states, some adults may be eligible to enroll simultaneously in 2 federally funded managed care systems: the Medicare Advantage (MA) program administered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Veterans Healthcare System (VA) administered by the Veterans Health Administration in the US Department of Veterans Affairs. Although the VA may collect reimbursements for care provided to veterans enrolled in private health plans, Section 1862 of the Social Security Act prohibits the VA from collecting any reimbursements from the Medicare program, including from MA plans.

Dual enrollment in the VA and MA presents a vexing policy problem. The federal government’s payments to private MA plans assume that these plans are responsible for providing comprehensive care for their enrollees and are solely responsible for paying the costs of Medicare-covered services.1 If enrollees in MA plans simultaneously receive Medicare-covered services from another federally-funded hospital or other health care facility, and this facility cannot be reimbursed, then the government has made 2 payments for the same service.2–4 In this scenario, private Medicare plans receive taxpayer-funded subsidies to insure veterans who in turn use another government-funded health system to receive medical care.

Given the severe financial pressure confronting the Medicare program and the federal budget, the nature and extent of services provided to these beneficiaries and the amount of duplicate payments for them should be quantified. Using national VA and MA administrative data from 2004 to 2009, we examined the prevalence of dual enrollment, the use of outpatient and acute inpatient care in the VA and MA, and the costs of Medicare-covered services incurred by the VA to care for MA enrollees.

METHODS

Source of Data/Study Population

We merged VA enrollment records from 2004 to 2009 with the Medicare denominator file from the corresponding years to derive the national population of veterans with at least 1 month of simultaneous enrollment in the VA and a MA plan. We used a 1-month threshold to define dual enrollment as the Medicare denominator file defines the duration of managed care enrollment in monthly increments. Among these dual VA-MA enrollees, we linked the data to VA utilization and cost records to determine use of all VA-financed inpatient care, outpatient care, fee-basis care, and prescription drugs during the same month that the veteran was enrolled in an MA plan. Fee-basis care refers to VA-financed services that are delivered in private-sector settings when VA care is not available or for other specified reasons. Our linking variables were a combination of the social security number, date of birth, and sex, which is a validated and conservative method of linking VA and Medicare administrative data.5

To determine the simultaneous use of services in the MA plan, we linked data from 2004–2009 to Medicare Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) data, which include individual-level information on utilization of acute medical and surgical inpatient care and ambulatory encounters. With the exception of Medicare private fee-for-service plans, all MA plans are required to report these data to the CMS.

Current federal law allows the VA to bill private health plans; however, the VA is not authorized to collect reimbursements from Medicare-funded health plans (although 1 prior study using data from 1993–1994 found that the VA collected payments from some Medicare managed care plans).2 Therefore, we obtained data from the VA’s Medical Care Cost Recovery file, which contains all submitted and recovered claims to third-party insurers on behalf of care provided by the VA.

For analyses of enrollment and cost trends, our study population consisted of 1 245 210 individuals who were simultaneously enrolled in the VA and MA (or its predecessor Medicare + Choice) for at least 1 month between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2009. For analyses of utilization of health services in VA and MA health plans, our primary study population consisted of 1 066 750 individuals who were simultaneously enrolled in the VA and a HEDIS-reporting MA plan during the study period.

Cost of VA Services

The VA is funded primarily by a Congressional appropriation and therefore its utilization data do not assign costs or charges to specific patient encounters. To estimate the cost of VA services provided to veterans who were simultaneously enrolled in MA plans, we used average cost methods developed by the VA’s Health Economics Resource Center. Detailed descriptions of these methods, modeling assumptions, and comparisons to alternative costing methods have been published previously.6,7

The average-cost method is used to model the cost of services based on hypothetical Medicare payments. For acute inpatient services, the model estimates costs using the relative value units and associated weights from Medicare’s diagnostic related group payment system. For outpatient services, the model uses the relative value units of Medicare’s resource-based relative value system and the current procedures and terminology codes assigned to each encounter. The model derives the cost of inpatient stays in rehabilitation, psychiatric, substance abuse, intermediate medicine treatment units, and extended care facilities by using Medicare data and resource utilization groups to estimate the average cost of a day of stay, and applying it to estimate the cost of care. Extended care and rehabilitation services provided in VA community-based living centers were not included in the cost estimates, as we were unable to determine which of these services represented post-acute care eligible for Medicare coverage.

To derive the cost of fee-basis care, we used the actual payments that the VA made to finance private inpatient and outpatient care for dual enrollees. Finally, we obtained direct VA pharmacy cost data to determine the cost of prescription drugs provided to outpatients. We adjusted all cost estimates to reflect 2009 dollars using the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Use of Medicare and VA Services

The Medicare HEDIS data provide annual summary variables of the total number of outpatient visits, and acute inpatient medical and surgical admissions and hospital days financed by the enrollee’s MA plan. We applied the HEDIS specifications to VA utilization records to create similar summary variables for each dual enrollee, considering only the VA utilization that took place during the same month of enrollment in an MA plan. Therefore, for each dual enrollee, we derived the annual use of outpatient and acute inpatient services that occurred in the VA and the enrollee’s MA plan using a consistent definition and time period in both data sets.

Analyses

For each year, we determined the number of VA/MA dual enrollees, the proportion receiving care in the VA in each year, and the cost of VA-provided health services. For dual enrollees in HEDIS-reporting plans, we determined the demographic characteristics and use of services among the following groups of dual VA/MA enrollees: (1) exclusive VA users; (2) VA /MA dual users; (3) exclusive MA users; and (4) nonusers of outpatient or acute inpatient care. Race and ethnicity status were obtained from the Medicare enrollment file. We used χ2 and analysis of variance tests to determine whether characteristics differed among these groups.

We calculated the proportionate reliance on VA outpatient care using the following formula: (VA outpatient visits + MA outpatient visits). We performed similar calculations for inpatient medical and surgical utilization. A sensitivity analysis, excluding 9% of beneficiaries who enrolled in their MA plan after January or exited their MA plan prior to December, yielded similar findings. Finally, we determined the proportion of VA enrollees and the proportion of VA users within each MA plan in 2009 and identified the 10 MA plans with the highest proportion of plan members who were using VA services.

The study was approved by the Providence VA Medical Center institutional review board; the requirement for informed consent was waived. All analyses were performed using SAS Statistical Software (version 9.2) and are reported with 2-tailed P values with α of .05.

RESULTS

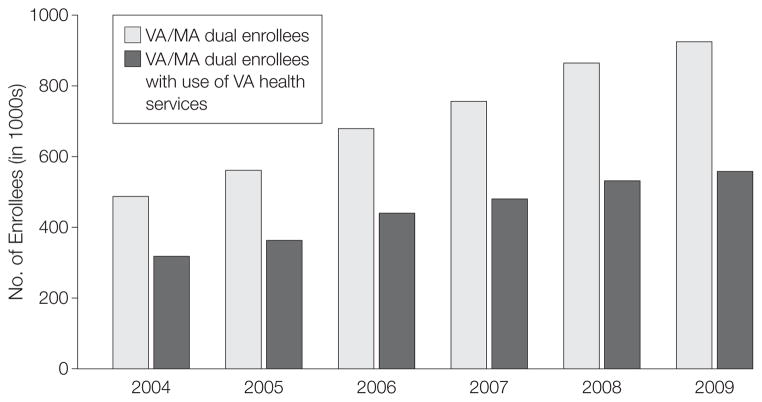

The number of individuals concurrently enrolled in the VA and MA plans for at least 1 month between 2004 and 2009 was 1 245 210. The number of dual enrollees increased from 485 651 in 2004 to 924 792 in 2009 (FIGURE 1). The number of dual enrollees using VA services increased from 316 281 in 2004 to 557 208 in 2009. In 2009, 8% of the MA population was enrolled in the VA and 5% of MA beneficiaries were VA users. The mean and median durations of dual enrollment during the entire study period were 37 and 35 months, respectively. The mean and median durations of dual enrollment during the calendar year were 11 months and 12 months, respectively.

Figure 1.

Trends in Dual Enrollment in VA and Medicare Advantage (MA), 2004–2009

VA indicates Veterans Affairs health care system.

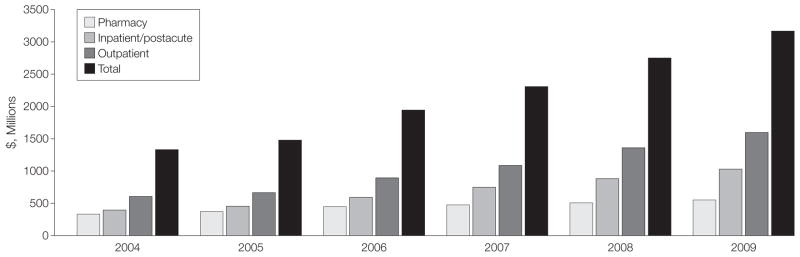

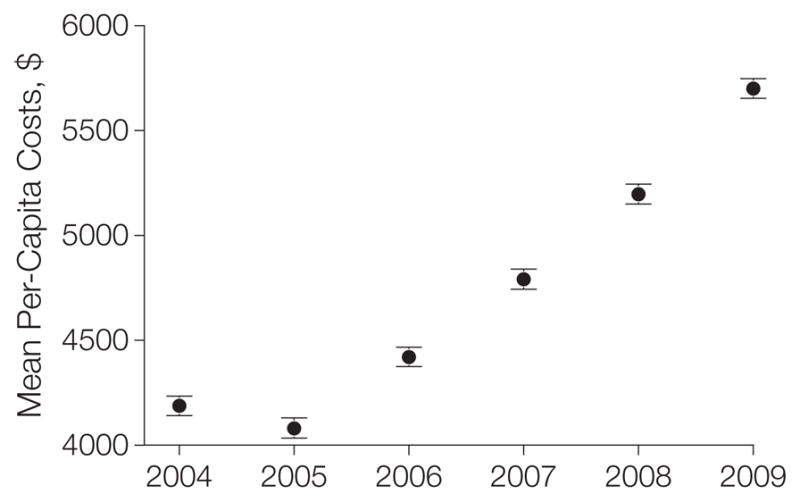

The total estimated cost of VA care (in 2009 dollars) for MA enrollees was $13.0 billion over 6 years, increasing from $1.3 billion to $3.2 billion per year (FIGURE 2). The largest component of this spending was outpatient care, followed by acute and postacute inpatient care, then prescription drugs. The annual costs of VA-financed fee-basis care increased by a factor of 5 during the study period (from $52 million in 2004 to $249 million in 2009), and represented approximately 8% of VA total spending for this population in 2009. Nonacute and psychiatric inpatient care represented 5% and 2% of health care spending, respectively. Among VA users enrolled in MA plans, the mean estimated per-capita VA costs increased from $4192 (95% CI, $4143–$4240) in 2004 to $5696 (95% CI, $5650–$5742) in 2009 (FIGURE 3). The estimated per-capita VA costs for non-drug services increased from $3264 (95% CI, $3218–$3310) in 2004 to $4849 (95% CI, $4806–$4893) in 2009.

Figure 2.

Estimated VA Health Care Costs for Medicare Advantage Enrollees, 2004–2009

VA indicates Veterans Affairs health care system.

Figure 3.

Estimated Per-Capita VA Health Care Costs for Medicare Advantage Enrollees, 2004–2009

Error bars indicate 95% CIs. VA indicates Veterans Affairs health care system.

Among dual enrollees, 10% exclusively used the VA for outpatient and acute inpatient services, 35% exclusively used the MA plan, 50% used both the VA and MA, and 4% received no services during the calendar year (TABLE 1). Compared with dual users and exclusive MA users, exclusive VA users were younger and more likely to be black and to reside in the South. Exclusive VA users had more annual outpatient visits but less acute inpatient care than did exclusive MA users (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics and Health Service Utilization of Individuals Dually Enrolled in the VA and Medicare Advantage, 2004–2009a

| Users

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VA Only | VA/MA Dual | MA Only | Nonusers | |

| Person-years, No. | 361 762 | 1 756 143 1 232 042 | 138 492 | |

|

| ||||

| Unique individuals, No. | 210 196 | 630 878 | 511 621 | 109 006 |

|

| ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 72.1 (9.2) | 75.0 (7.9) | 74.9 (7.9) | 72.3 (9.1) |

|

| ||||

| Women, % | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

|

| ||||

| Race, % | ||||

| White | 78 | 91 | 89 | 82 |

|

| ||||

| Black | 18 | 6 | 7 | 14 |

|

| ||||

| Other | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

|

| ||||

| Census region, % | ||||

| Northeast | 17 | 29 | 27 | 21 |

|

| ||||

| Midwest | 18 | 18 | 14 | 16 |

|

| ||||

| South | 35 | 29 | 26 | 31 |

|

| ||||

| West | 26 | 22 | 31 | 29 |

|

| ||||

| Outside census regions | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

|

| ||||

| Year, % | ||||

| 2004 | 13 | 14 | 12 | 16 |

|

| ||||

| 2005 | 15 | 15 | 13 | 18 |

|

| ||||

| 2006 | 15 | 15 | 13 | 16 |

|

| ||||

| 2007 | 15 | 16 | 16 | 15 |

|

| ||||

| 2008 | 20 | 20 | 22 | 17 |

|

| ||||

| 2009 | 22 | 21 | 24 | 18 |

|

| ||||

| Annual outpatient visits | ||||

| In the VA, mean (SD), No. | 16.1 (29.2) | 8.8 (19.1) | NA | NA |

|

| ||||

| In the VA, median (range), No. | 8 (0–754) | 4 (0–771) | NA | NA |

|

| ||||

| In MA, mean (SD), No. | NA | 8.9 (8.0) | 9.2 (8.3) | NA |

|

| ||||

| In MA, median (range), No. | NA | 7 (0–363) | 7 (0–426) | NA |

|

| ||||

| Annual acute inpatient days | ||||

| In the VA, mean (SD), No. | 1.2 (7.0) | 0.4 (3.7) | NA | NA |

|

| ||||

| In the VA, median (range), No. | 0 (0–365) | 0 (0–365) | NA | NA |

|

| ||||

| In MA, mean (SD), No. | NA | 1.6 (5.8) | 1.9 (6.9) | NA |

|

| ||||

| In MA, median (range), No. | NA | 0 (0–323) | 0 (0–366) | NA |

Abbreviations: MA, Medicare Advantage; NA, not available; VA, Veterans Affairs health care system.

P value is less than .001 for all comparisons between groups. Percentages may not sum to 100 because of rounding. Percentages and utilization numbers were calculated based on person-years as the unit of analysis.

The VA financed 44% of outpatient visits (n = 21 353 841), 15% of acute medical and surgical admissions (n=177 663), and 18% of acute medical and surgical hospital days (n=1 106 284) for the dually enrolled population. The proportion of outpatient visits financed by the VA increased from 42% in 2004 to 45% in 2009 (P <.001 for change). The proportion of acute medical and surgical admissions financed by the VA increased from 13% in 2004 to 17% in 2009 (P <.001 for change).

Within each of the 419 MA plans participating in Medicare in 2009, the mean proportion of VA enrollment was 8% (interquartile range, 6%–10%; range, 0.5%–21%) and the mean proportion of the plan’s enrollees with use of VA services was 7% (interquartile range, 5%–9%; range, 0.2%–16%). The 10 MA plans with the highest proportion of enrollees using VA services in 2009 are shown in TABLE 2. All but 1 of these plans had a for-profit tax status; 5 were located in Florida.

Table 2.

Ten Medicare Advantage Contracts With the Highest Proportions of Enrollees With VA Use in 2009

| CMS Contract No. | Plan Name | State | Total Plan Enrollment | Proportion Using VA Care, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H5594 | Optimum Healthcare | Florida | 5277 | 15.6 |

| H5262 | Gundersen Lutheran Health Plan | Wisconsin | 10 901 | 12.2 |

| H5427 | Freedom Health | Florida | 42 998 | 12.2 |

| H5697 | Erickson Advantage | Pennsylvania | 1065 | 12.1 |

| H1651 | Medical Associates Health Plan | Iowa | 5912 | 11.5 |

| H3044 | Welborn Health Plans | Indiana | 1776 | 10.8 |

| H5402 | Quality Health Plans | Florida | 15 872 | 10.7 |

| H5404 | Universal Health Care | Florida | 21 097 | 10.7 |

| H5696 | Physicians United Plan | Florida | 20 893 | 10.5 |

| H1468 | Humana Benefit Plan of Illinois | Illinois | 1095 | 10.2 |

Abbreviations: CMS, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; VA, Veterans Affairs health care system.

In 2009, the VA submitted collection requests to private insurers totaling $52.3 million on behalf of care provided to MA enrollees (amounting to 2% of the total cost of care for these enrollees in 2009). Of these requests, the VA collected $9.4 million for care (18% of the billed amount; 0.3% of the total cost of care).

COMMENT

Managed care integrates the financing and delivery of care with the goals of improving quality and reducing costs. Although managed care can take many forms in the United States, its fundamental organizing principle is that a single accountable entity receives a prospective payment to provide, coordinate, and monitor the provision of health services to a defined population of patients.

In this study of the costs and utilization of services for dual enrollees in the VA and MA managed care plans, we found that the federal government spent a substantial and increasing amount of funds in 2 separate managed care programs for care of the same individual. We estimate that the total cost of Medicare-covered services spent in the VA to deliver care to MA enrollees was approximately $13.0 billion from 2004 to 2009. In 2009, VA spending for this population amounted to 10% of the VA’s annual operating budget for medical services.8 Among MA plans, the proportion of beneficiaries eligible for VA care ranged from 0.5% to 21% and the proportion of VA users within these plans ranged from 0.2% to 16%. The VA financed 44% of out patient visits, 15% of acute medical and surgical inpatient admissions, and 18% of acute medical and surgical hospital days for this dually enrolled population, and these proportions increased from 2004 to 2009. Because the VA recovered almost no reimbursements from MA plans, our study suggests that private MA plans may benefit from a nun-recognized public subsidy as their “risk” of paying for health services for veterans is mitigated because these same services are delivered by another tax-funded health care program.

Our findings extend those from a number of studies of dual use of the VA and the traditional Medicare fee-for-service program.9–15 Like these other studies, we found that reliance on the VA is greater for outpatient care and lower for acute inpatient care. Further, individuals who exclusively rely on the VA for health services received approximately 180% more annual outpatient visits but 37% fewer annual acute inpatient days than did those exclusively receiving care in the MA program. This phenomenon may result from the larger distances that some veterans must travel to receive care in VA medical centers, which may reduce use of VA care for urgently or emergently needed treatments.9,12,14

Payments to Medicare Advantage plans derive in part from per-capita spending among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries residing in the same county, raising the possibility that use of VA services among fee-for-service beneficiaries may offset Medicare expenditures and therefore reduce payment rates to MA plans. For this reason, the 2008 Medicare Improvement for Patient and Providers Act directed the CMS Office of the Actuary to examine the effect of VA use on county fee-for-service spending rates.16

In 2009, the CMS Office of the Actuary concluded that the effect of VA use on fee-for-service spending rates was minimal for approximately 98% of US counties and attributed fee-for-service spending increases in the other 2% of counties to random fluctuations rather than an underlying difference between the veteran and nonveteran populations. Therefore, CMS decided that it did not need to adjust MA payment rates to account for use of the VA by fee-for-service beneficiaries. We searched for additional public comments by the CMS on this issue and did not identify any further changes in policy since 2009.

Of note, the 2008 Medicare Improvement for Patient and Providers Act did not authorize the CMS to study whether the use of VA services among MA beneficiaries may yield overpayments to MA plans. Our study strongly suggests that federal policymakers should monitor the use of VA services among MA-enrolled veterans and modify payments to MA plans accordingly, particularly given the large plan-level variations in veteran enrollment, the rapid growth of VA spending among this population, and the strong financial incentive for private MA plans to shift the cost of service delivery onto a public payer.

Policymakers could consider 2 broad approaches to reducing duplicative expenditures. First, the VA could be authorized to collect reimbursements from MA plans for covered services, just as the VA currently collects payments from private health insurers for non-Medicare patients.17 Although the Social Security Act prohibits the VA from collecting any reimbursements from the Medicare program, this law was enacted before the introduction of managed care plans to the Medicare program in 1982. This provision may therefore be anachronistic for private MA plans.

A second approach may involve adjusting payments to MA plans on behalf of veterans who receive most or all of their care in the VA. For example, we found that 10% of dual enrollees exclusively received care in the VA and that approximately half of outpatient encounters for the dually enrolled population took place in the VA. Medicare might reconsider the current practice of fully funding managed care plans on behalf of beneficiaries who primarily receive care in the VA.

Our study had important limitations. First, we were unable to quantify the amount of excess federal payments to Medicare Advantage plans on behalf of VA enrollees. Such an analysis would require information on MA payment rates, hierarchical condition classification risk scores, and MA claims—data that are unavailable to researchers. Therefore, we caution that the $13 billion in VA spending over 6 years to provide services to MA enrollees does not represent the precise level of “overpayment” to MA plans. As noted by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, use of the VA by Medicare beneficiaries may affect hierarchical condition classification risk scores, which are used to risk-adjust payments to MA plans.18 For instance, offsetting use of the VA may attenuate the number of co-morbid conditions captured in MA claims, and by extension, hierarchical condition classification risk scores and payments to MA plans.

Second, the study was not designed to assess the effect of dual use on redundant services, uncoordinated care, or health outcomes. Given prior research on the negative consequences of fragmented financing for VA enrollees, these questions should be explored in future research.19

Third, it is possible that the coding of outpatient and inpatient visits in the VA may differ from classification of such visits in MA plans. Fourth, our exclusion of extended care and rehabilitation services in VA community-based living centers likely results in an underestimate of total VA costs that would have been covered by Medicare.

In conclusion, we found a substantial and increasing amount of potentially duplicative federal spending for individuals who are dually enrolled in the VA and MA. In light of the severe financial pressure facing the Medicare program, policymakers should consider measures to identify and eliminate these potentially redundant expenditures.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This material is based upon work supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development Service, and the NIA (5RC1AG036158).

Role of the Sponsors: The funders played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Dr Trivedi reports provision of consultancy services to RAND Corporation serving on a CMS technical expert panel to develop quality measures for Medicare Advantage and Special Needs Plans. Dr Mor reports board membership with PointRight, Inc; consultancy services to Navi-Health, Abt Associates Inc, HCRManorCare, Research Triangle Institute Inc; employment with National Institutes of Health, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the National Institute on Aging (NIA); grants or pending grants from the NIA Program Project and the VA Health Services Research & Development Service Investigator-Initiated Research; lectures or speakers bureau participation for Rutgers University, Harvard Kennedy School, and the University of California San Francisco Division of Geriatrics; stocks or stock options with PointRight; a grant from Kidney Care Partners; and a contract to Brown University from Pfizer to investigate cost of Alzheimer disease and related disorders. Dr Kizer reports board membership with Humana Veterans Healthcare System; consultancy services with the Alaska VA Health System; and lecture or speakers bureau participation with the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr Grebla and Yoon and Ms Jiang report no disclosures.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Author Contributions: Dr Trivedi had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Trivedi, Mor, Kizer.

Acquisition of data: Trivedi, Jiang.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Trivedi, Grebla, Jiang, Yoon, Mor, Kizer.

Drafting of the manuscript: Trivedi, Grebla.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Jiang, Yoon, Mor, Kizer.

Statistical analysis: Trivedi, Grebla, Jiang.

Obtained funding: Trivedi.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Grebla, Kizer.

Study supervision: Trivedi, Mor, Kizer.

References

- 1.McGuire TG, Newhouse JP, Sinaiko AD. An economic history of Medicare part C. Milbank Q. 2011;89(2):289–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Passman LJ, Garcia RE, Campbell L, Winter E. Elderly veterans receiving care at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center while enrolled in Medicare-financed HMOs: is the taxpayer paying twice? J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(4):247–249. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.012004247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hester EJ, Cook DJ, Robbins LJ. The VA and Medicare HMOs—complementary or redundant? N Engl J Med. 2005;353(12):1302–1303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc051890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeVito CA, Morgan RO, Virnig BA. Use of Veterans Affairs medical care by enrollees in Medicare HMOs. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(14):1013–1014. doi: 10.1056/nejm199710023371418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleming C, Fisher ES, Chang CH, Bubolz TA, Malenka DJ. Studying outcomes and hospital utilization in the elderly: the advantages of a merged database for Medicare and Veterans Affairs hospitals. Med Care. 1992;30(5):377–391. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199205000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phibbs CS, Bhandari A, Yu W, Barnett PG. Estimating the costs of VA ambulatory care. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60(3 suppl):54S–73S. doi: 10.1177/1077558703256725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagner TH, Chen S, Barnett PG. Using average cost methods to estimate encounter-level costs in the VA. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60(3 suppl):15S–36S. doi: 10.1177/1077558703256485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panangala SV. Veterans Medical Care: FY2010 Appropriations. Congressional Research Service; [Accessed June 9, 2012]. http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA513830. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burgess JF, Jr, DeFiore DA. The effect of distance to VA facilities on the choice and level of utilization of VA outpatient services. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39 (1):95–104. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byrne MM, Kuebeler M, Pietz K, Petersen LA. Effect of using information from only one system for dually eligible health care users. Med Care. 2006;44(8):768–773. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000218786.44722.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carey K, Montez-Rath ME, Rosen AK, Christiansen CL, Loveland S, Ettner SL. Use of VA and Medicare services by dually eligible veterans with psychiatric problems. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(4):1164–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00840.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hynes DM, Koelling K, Stroupe K, et al. Veterans’ access to and use of Medicare and Veterans Affairs health care. Med Care. 2007;45(3):214–223. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000244657.90074.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mooney C, Zwanziger J, Phibbs CS, Schmitt S. Is travel distance a barrier to veterans’ use of VA hospitals for medical surgical care? Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(12):1743–1755. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00414-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petersen LA, Byrne MM, Daw CN, Hasche J, Reis B, Pietz K. Relationship between clinical conditions and use of Veterans Affairs health care among Medicare-enrolled veterans. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(3):762–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01107.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen Y, Hendricks A, Zhang S, Kazis LE. VHA enrollees’ health care coverage and use of care. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60(2):253–267. doi: 10.1177/1077558703060002007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed June 9, 2012];Advance notice of methodological changes for calendar year (CY) 2010 for Medicare Advantage capitation rates and Medicare Advantage and Part C and Part D payment policies. 2009 http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/downloads/Advance2010.pdf.

- 17.US Government Accountability Office. VA medical care: increasing recoveries from private health insurers will prove difficult. [Accessed March 15, 2012];HEHS-98-4. 1997 Oct 17; http://www.gao.gov/archive/1998/he98004.pdf.

- 18.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) [Accessed June 9, 2012];Report to the Congress: improving incentives in the Medicare program. 2009 Jun; http://www.medpac.gov/documents/jun09_entirereport.pdf.

- 19.Pizer SD, Gardner JA. Is fragmented financing bad for your health? Inquiry. 2011;48(2):109–122. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_48.02.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]