Abstract

Rapid diagnostic tests have the potential to reduce the overtreatment of malaria by 95%, but time and extensive logistical, behavioural, and technical interventions may be required to achieve this, argue Eleanor Ochodo and colleagues

Medical care of populations often treads a fine line between the differing harms of underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis. Underdiagnosis may mean that a disease is advanced by the time it is detected, increasing the risk of death, whereas overdiagnosis leads to healthy people being labelled as sick and treated with drugs that will be of no benefit and may even cause harm.1 How much underdiagnosis or overdiagnosis can be regarded as “reasonable” is a value judgement and may vary between different stakeholders: consumers, clinicians, or policy makers. It will also vary between diseases and populations and be related to the severity of the illness, the benefits and harms of the treatment, the cost of the treatment, the availability of reliable tests, and the public health effects of the approach taken.

Malaria is an interesting case study because the perceived benefits of overdiagnosis (few missed cases), and the potential harms of underdiagnosis (unpredictable progression to severe malaria and death) led to the promotion of substantial overdiagnosis and overtreatment for many years.2 3 4 Up until about 15 years ago, policy makers, including the World Health Organization, promoted a strategy known as “presumptive treatment of malaria” in areas where diagnostic testing (by light microscopy) was unavailable. This strategy recommended that all patients with fever were treated with antimalarials, regardless of the presence or absence of signs of other illnesses, and accepted the substantial overuse of chloroquine because it was cheap and well tolerated.2 3

However, the balance has now swung the other way, with policy makers and clinicians increasingly concerned about the clinical, financial, and public health harms associated with overtreatment. The currently recommended firstline antimalarial drugs (artemisinin based combination therapies) are not cheap and malaria prevalence is falling in many countries, raising the relative importance of diagnosing and treating other causes of fever.4 5 6 Consequently, the development of rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) that can be used in basic healthcare services in remote settings led the WHO to recommend a switch to universal parasitological testing before treatment in 2010.5 Despite the subsequent rapid scale-up of rapid tests, overtreatment remains a problem. We examine the drivers and examine the potential strategies to overcome these.

Why might overtreatment still occur?

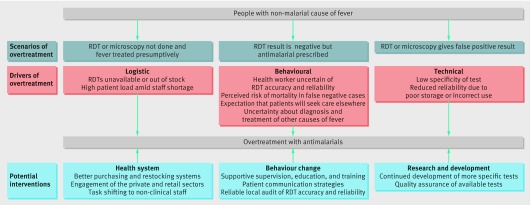

The figure outlines three scenarios that can result in overtreatment of malaria, the different drivers, and possible solutions.

Fig 1 Logic framework of scenarios and drivers of overtreatment despite rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) with potential interventions

Scenario 1: test not done; fever treated presumptively

The latest WHO data show that the reported rate of diagnostic testing in the African region increased from 41% in 2010 to 65% in 2014.6 This is impressive progress in the public sector but does not measure the scale of the problem in the private and retail sectors. In Uganda, around two thirds of people seek malaria treatment from retail drug stores, where testing is rarely done,7 and this situation seems to be replicated in other African countries.4 In Kenya, over-the-counter malaria medicines were shown to be the most popular first response to fever in children and adults with acute illnesses.8

Another reason for not testing is shortage of rapid tests. Cross-sectional studies in Tanzania,9 Mozambique,10 and Democratic Republic of Congo11 estimated that 50%, 59%, and 62%, respectively, of the facilities surveyed did not have RDTs in stock. Even when RDTs are available, they may not be universally used. In one study from Tanzania staff reported reverting to presumptive treatment when patient workload was high or during staff shortages.9

Scenario 2: test result is false positive

A small number of false positive results are inevitable with any diagnostic test, but the high specificity of available RDTs means this number is likely to be negligible in comparison with the “false positives” of presumptive diagnosis.

Table 1 presents the test outcomes for a hypothetical cohort of 100 patients with fever tested with the most commonly used RDTs in settings with different prevalences of malaria. The sensitivity and specificity estimates are derived from meta-analytical summaries of 71 studies included in the Cochrane review of RDT accuracy.12

Table 1.

Outcomes of rapid diagnostic testing in hypothetical cohorts of 100 people presenting with fever in settings with different malaria prevalences*

| Pretest probability of positive result (%) | No of cases/100 people (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-malarial cause of fever | Malaria is true cause of fever | |||||

| False positives† | True negatives‡ | True positives§ | False negatives¶ | |||

| 5 | 5 (3 to 6) | 90 (89 to 92) | 5 (5 to 5) | 0 (0 to 0) | ||

| 30 | 4 (3 to 5) | 66 (65 to 67) | 29 (28 to 29) | 2 (1 to 2) | ||

| 60 | 2 (2 to 3) | 38 (37 to 38) | 57 (56 to 58) | 3 (2 to 4) | ||

| 80 | 1 (1 to 1) | 19 (19 to 19) | 76 (75 to 77) | 5 (3 to 5) | ||

*Type 1 HRP-2 rapid diagnostic test (RDT) with average sensitivity of 94.8% (95% CI 93.1 to 96.1) and specificity 95.2% (95% CI 93.2 to 96.7).12

†Number of unnecessary prescriptions that would still occur when using RDTs (the true cause of fever may also go untreated).

‡Number of unnecessary antimalarial prescriptions that could be avoided if RDTs are used instead of presumptive treatment.

§Number of people correctly diagnosed with malaria by the RDT.

¶Number of people with malaria who would be sent home without antimalarials because of a negative RDT result.

In all four settings RDTs have the potential to reduce unnecessary prescriptions by around 95% compared with presumptive treatment. In absolute terms this means preventing between 19 and 90 unnecessary prescriptions per 100 people tested. The largest number of false positive results would occur in the settings of lowest prevalence but remain very small.

Scenario 3: test result is negative but antimalarial drugs are still prescribed

Increased use of RDTs will be a waste of resources unless health workers use the result to guide prescribing. In a Cochrane review of studies that randomly assigned health workers to using RDT based algorithms or clinical diagnosis, compliance with the RDT result was highly variable across studies. In the most extreme example health workers prescribed antimalarial drugs to 81% of people with negative results.13 In trials in which health workers adhered to the test result antimalarial prescriptions were reduced by up to three quarters. These are early trials and we would expect adherence to improve during programmatic use.

Several qualitative studies have explored the reasons for health workers ignoring the test result.14 15 16 17 Commonly cited reasons are a lack of trust in the accuracy of tests; fear of the consequences of missing a true malaria case; confusion about the change from previous recommendations; pressure to prescribe from patients; and uncertainty about how to manage the other causes of fever. Studies among patients also report a lack of trust in the test’s accuracy, enhanced by conflicting advice from different health facilities and feeling better after taking antimalarial drugs even when the test result is negative.

What are the risks associated with RDTs?

Previous training and guidance to health workers emphasised the danger of missing a case of malaria and sending a child home without treatment.2 This ingrained belief is likely to take time to change, and health workers will require evidence based reassurance that this new policy is safe.

How common are false negative results?

The hypothetical cohorts in table 1 indicate that the balance of benefit and harms with RDTs is most favourable in areas with low malarial endemicity. In settings with a pretest probability of 5% (5% of fevers are due to malaria), using RDTs could prevent 90 unnecessary antimalarial prescriptions per 100 people tested, with less than one true malaria case being missed.

As the pretest probability gets higher, up to 60%, the balance is closer: with 38 unnecessary prescriptions prevented at the cost of missing three true malaria cases: and in truly epidemic conditions with a pretest probability of 80% there is an argument that reverting to presumptive diagnosis would be the safest and certainly most cost effective thing to do.

While this may be reassuring for those in low endemic settings, concerns have been raised that clinical malaria can occur at parasite counts below those detectable by standard RDTs and the risk of progression to severe malaria may be higher because of lower immunity.18 These potential risks need quantifying.

What is the risk of severe malaria developing in people sent home without treatment?

In the Cochrane review by Odaga et al, five trials randomised health workers to using RDT diagnosis or clinical diagnosis (presumptive treatment). Despite large reductions in the use of antimalarials when health workers adhered to the RDT result, there were no clinically important differences in the number of people remaining unwell four to seven days later.13

We also found a longitudinal study from Tanzania19 that followed up children with negative results for two weeks after being discharged without antimalarials. Of 1000 children with fever who had RDTs, 603 (60%) tested negative, and it is worth noting the average sensitivity of RDTs would predict around 20 missed cases in this setting. Over the course of the study 587 (97.3%) got better without antimalarials, three (0.5%) had subsequent positive test results at re-attendance and were treated, two (0.3%) died (of sepsis and pneumonia with repeated negative RDT results), and 12 (2%) were lost to follow-up.

This study was done in programmatic conditions close to routine practice and may offer some reassurance that if patients with persisting symptoms are able to return to the health post they will, and without serious consequences. Similar studies and local audits may help to reassure health workers further.

What strategies might be used to reduce overtreatment?

Clearly, countries need a range of strategies across all levels of the health system to fully implement universal testing. Table 2 presents some of the approaches currently being evaluated.

Table 2.

Potential strategies to curb overtreatment of fever as malaria

| Problem | Established approaches | Experimental approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1: test not done, fever treated presumptively | ||

| RDT shortages | - | Using technology such as short text messaging (SMS), internet, and electronic mapping to track stock of RDTs 20 21 |

| Limited RDT availability in private drug retail sector | - | Provision of free or subsidised RDTs through the private sector22 23 |

| Staff shortages and high patient load in health centres | Use of community health workers to diagnose and treat uncomplicated malaria24 25 | - |

| Scenario 2: test positive but the result is a false positive | ||

| Low specificity of tests | Regular quality testing of RDTs from manufacturers by WHO26 | Enabling external QA of reading and interpretation of RDTs by sending test photographs via SMS11 |

| Urine or fluorescent RDTs27 | ||

| Scenario 3: test negative; but antimalarial drugs are still prescribed | ||

| Uncertainty about RDT accuracy and perceived risk of mortality in people with false negatives results | Interactive educational meetings28 Multifaceted interventions including health workers, patients and the public 28 29 30 |

Evidence based training on the accuracy of RDTs and safety of not treating when results are negative31 32 |

| Accessible formats for guidelines, e.g. summaries33 | Electronic or mobile friendly guidelines34 | |

| Uncertainty about how to manage fever when test is negative | Integrated case management of malarial and non-malarial causes of fever24 25 | Improving referral paths for patients with negative results35 |

| Expectation that patients will seek treatment elsewhere | Mass media interventions38 | Incorporating patient communication skills in training packages of health workers32 36 |

| Use of clinic posters, decision aids and patient pamphlets and community awareness programmes32 36 | ||

| SMS reminders reiterating the treatment advice based on RDT result37 | ||

Improved management could help stop RDTs becoming out of stock, and mobile phone technology has been touted as a potential solution. A mobile phone short messaging service (SMS) and web based system was evaluated in rural districts in Tanzania20 and Kenya.21 Mobile phones have also been evaluated as a means to improve quality assurance of RDTs11 and to enable easy access to guidelines and clinical decision aids.37 39

A subsidy on artemisinin based combination therapy had some success in increasing its availability in the private sector, and some have advocated for a similar approach to promote the use of RDTs by private drug sellers.22 40 However, others argue that the economics and effects of a subsidy are far from straightforward.41

The effectiveness of training or education required to change the behaviour of both health workers and patients has also been under evaluation. Simple, short training for health workers on using RDTs was evaluated in Cameroon,31 and more complex training interventions including both the community and patients have been evaluated in three arm cluster randomised trials in Tanzania32 and Nigeria.36

Changing behaviour is rarely easy, and as well as generating their own evidence, malaria experts should draw on the lessons from similar efforts to reduce antibiotic prescribing in other illnesses.28 29 30

In conclusion, universal testing for malaria is a major policy shift that will take time and extensive resources to fully implement across sub-Saharan Africa. Success will require different interventions across public, private, and retail sectors.

Key messages

Universal testing for malaria will take time and extensive resources to fully implement across sub-Saharan Africa

Interventions are required to overcome logistical health system constraints and change the beliefs and behaviour of health workers and patients

Further developments to improve the accuracy of tests are also important

Contributors and sources: EO has a five year research experience in evidence based healthcare with special focus on diagnostic tests. PG and DS have a longstanding experience in evidence synthesis for global health; they coordinate the Cochrane infectious disease group in Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and lead a network of over 300 people in synthesising evidence to inform health decisions in low and middle income countries. PG is also a member of the WHO malaria technical guidelines group on malaria treatment. EO conceived this article after discussions at a symposium on overdiagnosis. Evidence from systematic reviews, primary studies and technical reports was used to prepare this article. EO had the original idea, wrote the first draft, provided examples, and coordinated the paper; PG provided examples and contributed to the manuscript; DS guided structure and content of the paper, provided examples, and contributed to the manuscript. All authors have agreed with submission and seen the final manuscript. EO is the guarantor of the article.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare that we have no competing interests.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Cite this as: BMJ 2016;352:i107

References

- 1.Moynihan R, Henry D, Moons KGM. Using evidence to combat overdiagnosis and overtreatment: evaluating treatments, tests, and disease definitions in the time of too much. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. 2006. www.afro.who.int/en/downloads/cat_view/1501-english/1235-clusters-and-programmes/795-malaria-mal.html?start=15

- 3.D’Acremont V, Kahama-Maro J, Swai N, et al. Reduction of anti-malarial consumption after rapid diagnostic tests implementation in Dar es Salaam: a before-after and cluster randomized controlled study. Malaria J 2011;10:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao VB, Schellenberg D, Ghani AC. Overcoming health systems barriers to successful malaria treatment. Trends Parasitol 2013;29:164-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria: 2nd ed. 2010. www.afro.who.int/en/downloads/cat_view/1501-english/1235-clusters-and-programmes/795-malaria-mal.html?start=15.

- 6.WHO. World malaria report 2015. www.who.int/malaria/publications/world-malaria-report-2015/report/en/.

- 7.Chandler CI, Hall-Clifford R, Asaph T, et al. Introducing malaria rapid diagnostic tests at registered drug shops in Uganda: limitations of diagnostic testing in the reality of diagnosis. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:937-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abuya TO, Mutemi W, Karisa B, et al. Use of over-the-counter malaria medicines in children and adults in three districts in Kenya: implications for private medicine retailer interventions. Malaria J 2007;6:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mubi M, Kakoko D, Ngasala B, Premji Z, Peterson S, Björkman A, Mårtensson A. Malaria diagnosis and treatment practices following introduction of rapid diagnostic tests in Kibaha District, Coast Region, Tanzania. Malaria J 2013;12:293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasselback L, Crawford J, Chaluco T, Rajagopal S, Prosser W, Watson N. Rapid diagnostic test supply chain and consumption study in Cabo Delgado, Mozambique: estimating stock shortages and identifying drivers of stock-outs. Malaria J 2014;13:295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mukadi P, Gillet P, Lukuka A, Mbatshi J, et al. External quality assessment of reading and interpretation of malaria rapid diagnostic tests among 1849 end-users in the Democratic Republic of the Congo through Short Message Service (SMS). PloS One 2013;8:e71442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abba K, Deeks J, Olliaro P, Naing CM, et al. Rapid diagnostic tests for diagnosing uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in endemic countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;6:CD008122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Odaga J, Sinclair D, Lokong JA, Donegan S, Hopkins H, Garner P. Rapid diagnostic tests versus clinical diagnosis for managing people with fever in malaria endemic settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;4:CD008998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ansah EK, Reynolds J, Akanpigbiam S, Whitty CJ, Chandler CI. “Even if the test result is negative, they should be able to tell us what is wrong with us”: a qualitative study of patient expectations of rapid diagnostic tests for malaria. Malaria J 2013;12:258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandler CI, Mangham L, Njei AN, et al. “As a clinician, you are not managing lab results, you are managing the patient”: how the enactment of malaria at health facilities in Cameroon compares with new WHO guidelines for the use of malaria tests. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:1528-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandler CI, Whitty CJ, Ansah EK. How can malaria rapid diagnostic tests achieve their potential? A qualitative study of a trial at health facilities in Ghana. Malaria J 2010;9:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ezeoke OP, Ezumah NN, Chandler CC, et al. Exploring health providers’ and community perceptions and experiences with malaria tests in South-East Nigeria: a critical step towards appropriate treatment. Malaria J 2012;11:368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graz B, Willcox M, Szeless T, et al. “Test and treat” or presumptive treatment for malaria in high transmission situations? A reflection on the latest WHO guidelines. Malaria J 2011;10:136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Acremont V, Malila A, Swai N, et al. Withholding antimalarials in febrile children who have a negative result for a rapid diagnostic test. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51:506-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barrington J, Wereko-Brobby O, Ward P, et al. SMS for Life: a pilot project to improve anti-malarial drug supply management in rural Tanzania using standard technology. Malaria J 2010;9:298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Githinji S, Kigen S, Memusi D, et al. Reducing stock-outs of life saving malaria commodities using mobile phone text-messaging: SMS for life study in Kenya. PloS One 2013;8:e54066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ansah EK, Narh-Bana S, Affran-Bonful H, et al. The impact of providing rapid diagnostic malaria tests on fever management in the private retail sector in Ghana: a cluster randomized trial. BMJ 2015;350:h1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen J, Fink G, Berg K, et al. Feasibility of distributing rapid diagnostic tests for malaria in the retail sector: evidence from an implementation study in Uganda. PloS One 2012;7:e48296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruizendaal E, Dierictx S, Peeters Grietens K, Schallig HD, Pagnoni F, Mens PF. Success or failure of critical steps in community case management of malaria with rapid diagnostic tests: a systematic review. Malaria J 2014;13:229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith Paintain L, Willey B, Kedenge S, et al. Community health workers and stand-alone or integrated case management of malaria: a systematic literature review. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2014;91:461-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO. Malaria rapid diagnostic performance; summary results of WHO product testing of malaria RDTs: round 1-5 (2008-2013). 2014. www.finddiagnostics.org/export/sites/default/resource-centre/reports_brochures/docs/malaria_rdt_Round5_results-summary_eng.pdf

- 27.WHO. Malaria diagnostics landscape update. WHO, 2015.

- 28.Arnold SR, Straus SE. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices in ambulatory care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;4:CD003539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davey P, Brown E, Charani E, et al. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;4:CD003543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coxeter P, Del Mar CB, McGregor L, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision making to address antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;11:CD010907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mbacham WF, Mangham-Jefferies L, Cundill B, et al. Basic or enhanced clinician training to improve adherence to malaria treatment guidelines: a cluster-randomised trial in two areas of Cameroon. Lancet Global Health 2014;2:e346-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cundill B, Mbakilwa H, Chandler CI, et al. Prescriber and patient-oriented behavioural interventions to improve use of malaria rapid diagnostic tests in Tanzania: facility-based cluster randomised trial. BMC Med 2015;13:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fiander M, Grad R, Pluye P, et al. Interventions to increase the use of electronic health information by healthcare practitioners to improve clinical practice and patient outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;3:CD004749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurumop SF, Bullen C, Whittaker R, et al. Improving health worker adherence to malaria treatment guidelines in Papua New Guinea: feasibility and acceptability of a text message reminder service. PloS One 2013;8:e76578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nanyonjo A, Bagorogoza B, Kasteng F, et al. Estimating the cost of referral and willingness to pay for referral to higher-level health facilities: a case series study from an integrated community case management programme in Uganda. BMC Health Serv Resarch 2015;15:347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Onwujekwe O, Mangham-Jefferies L, Cundill B, et al. Effectiveness of provider and community interventions to improve treatment of uncomplicated malaria in Nigeria: a cluster randomized controlled trial. PloS One 2015;10:e0133832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Modrek S, Schatzkin E, De La Cruz A, et al. SMS messages increase adherence to rapid diagnostic test results among malaria patients: results from a pilot study in Nigeria. Malaria J 2014;13:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grilli R, Ramsay C, Minozzi S. Mass media interventions: effects on health services utilisation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;1:CD000389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zurovac D, Su RK, Akhwale WS, et al. The effect of mobile phone text-message reminders on Kenyan health workers’ adherence to malaria treatment guidelines a cluster randomised trial. Lancet 2011;378:795-803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lussiana C. Towards subsidized malaria rapid diagnostic tests. Lessons learned from the global subsidy of artemisinin-based combination therapies: a review. Health Policy Plan 2015;pii:czv028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Cohen J, Dupas P, Schaner S. Price subsidies, diagnostic tests, and targeting of malaria treatment: evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Am Econ Rev 2015;105:609-45. [Google Scholar]