Abstract

Background. Assessing healthcare utilization is important to identify weaknesses of healthcare systems, to outline action points for preventive measures and interventions, and to more accurately estimate the disease burden in a population.

Methods. A healthcare utilization survey was developed for the Typhoid Fever Surveillance in Africa Program (TSAP) to adjust incidences of salmonellosis determined through passive, healthcare facility–based surveillance. This cross-sectional survey was conducted at 11 sites in 9 sub-Saharan African countries. Demographic data and healthcare-seeking behavior were assessed at selected households. Overall and age-stratified percentages of each study population that sought healthcare at a TSAP healthcare facility and elsewhere were determined.

Results. Overall, 88% (1007/1145) and 81% (1811/2238) of the population in Polesgo and Nioko 2, Burkina Faso, respectively, and 63% (1636/2590) in Butajira, Ethiopia, sought healthcare for fever at any TSAP healthcare facility. A far smaller proportion—namely, 20%–45% of the population in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau (1743/3885), Pikine, Senegal (1473/4659), Wad-Medani, Sudan (861/3169), and Pietermaritzburg, South Africa (667/2819); 18% (483/2622) and 9% (197/2293) in Imerintsiatosika and Isotry, Madagascar, respectively; and 4% (127/3089) in Moshi, Tanzania—sought healthcare at a TSAP healthcare facility. Patients with fever preferred to visit pharmacies in Imerintsiatosika and Isotry, and favored self-management of fever in Moshi. Age-dependent differences in healthcare utilization were also observed within and across sites.

Conclusions. Healthcare utilization for fever varied greatly across sites, and revealed that not all studied populations were under optimal surveillance. This demonstrates the importance of assessing healthcare utilization. Survey data were pivotal for the adjustment of the program's estimates of salmonellosis and other conditions associated with fever.

Keywords: healthcare utilization, typhoid fever, sub-Saharan Africa

The United Nations has set the challenging goal of improving access to healthcare for important diseases and reproductive health and to make essential medication more affordable [1]. Recent estimates for the African Region have indicated that the healthcare infrastructure as assessed, for example, by the density of healthcare facilities, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/AIDS testing and counseling facilities, the number of health professionals, and community and traditional healthcare workers varied greatly for a given population [2]. In 2013, healthcare expenditures across Africa were covered by governmental and private resources at approximately equal proportions (Table 1). It has been reported that utilization of healthcare among infants, assessed through coverage of antenatal care and vaccination, differed considerably throughout Africa (Table 1). During 2007–2014, 49% of children with acute respiratory infections were taken to a healthcare facility (HCF) (36% were treated), and 49% of children aged <5 years received oral rehydration during diarrheal attacks [2].

Table 1.

Health Indicators for the African Region and by Country, Typhoid Fever Surveillance in Africa Program, 2011–2013

| Indicator |

African Region | Burkina Faso | Ethiopia | Ghana | Guinea-Bissau | Madagascar | Senegal | South Africa | Sudan | Tanzania | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demography | Population (in thousands; all ages; 2013) | 927 371 | 16 935 | 94 101 | 25 905 | 1704 | 22 925 | 14 133 | 52 776 | 37 964 | 49 253 |

| Population <15 y (%; 2013) | 42.4 | 45.5 | 42.7 | 38.4 | 41.4 | 42.4 | 43.5 | 29.5 | 41.2 | 44.8 | |

| Population >60 y (%; 2013) | 5 | 3.9 | 5.2 | 5.4 | 5.3 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 8.6 | 5 | 4.9 | |

| Life expectancy at birth (both sexes; 2013) | 58 | 59 | 65 | 63 | 54 | 64 | 64 | 60 | 63 (2012) | 63 | |

| Life expectancy at age 60 y (both sexes; 2013) | 17 | 15 | 18 | 17 | 15 | 17 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 18 | |

| Socioeconomics | HDIa rank (2013) | … | 181 | 173 | 138 | 177 | 155 | 163 | 118 | 166 | 159 |

| HDIa value (2013) | 0.502 (low) | 0.388 (low) | 0.435 (low) | 0.573 (medium) | 0.396 (low) | 0.498 (low) | 0.485 (low) | 0.658 (medium) | 0.473 (low) | 0.488 (low) | |

| Population living below $1.25 per day (%; both sexes; all ages) | 48.5 (2011) | 44.6 (2009) | 30.7 (2011) | 28.6 (2006) | 48.9 (2002) | 81.3 (2010) | 29.6 (2011) | 13.8 (2009) | 19.8 (2009) | 67.9 (2007) | |

| Underweight children <5 y (%; both sexes) | 24.9 (2013) | 26.2 (2010) | 25.2 (2014) | 13.4 (2011) | 18.1 (2010) | 36.8 (2004) | 16.8 (2013) | 8.7 (2008) | 27 (2006) | 13.6 (2011) | |

| Literacy rate among adults (%; ≥15 y; both sexes; 2007–2012) | 64 | 29 | 39 | 67 | 55 | 65 | 50 | 93 | 73 (2012) | 73 | |

| Population using improved drinking water (%; both sexes; all ages; 2012) | 63 (2010) | 82 | 52 | 87 | 74 | 50 | 74 | 95 | 55 | 53 | |

| Population using improved sanitation facilities (%; both sexes; all ages; 2012) | 34 (2010) | 19 | 24 | 14 | 20 | 14 | 52 | 74 | 24 | 12 | |

| Communicable diseases | Confirmed HIV cases (with and without AIDS; both sexes; all ages; 2013) | 24 700 000 | 110 000 | 790 000 | 220 000 | 41 000 | 54 000 | 39 000 | 6 300 000 | 49 000 | 1 400 000 |

| Confirmed malaria cases (both sexes; all ages; 2013) | 44 737 004 | 3 769 051 | 2 645 454 | 1 639 451 | 54 584 | 387 045 | 345 889 | 8 645 | 592 383 | 1 552 444 | |

| Confirmed TB (new, relapse) cases (both sexes; all ages; 2013) | 1 337 696 | 5520 | 131 677 | 15 606 | 2095 | 27 445 | 13 515 | 328 896 | 20 181 | 65 732 | |

| Mortality | Neonatal mortality rate (per 1000 live births; both sexes; 2013) | 30.5 | 26.9 | 27.5 | 29 | 44.0 | 21.4 | 23 | 14.8 | 29.9 | 20.7 |

| Under-5 mortality rate (per 1000 live births; both sexes; 2013) | 90.1 | 97.6 | 64.4 | 78 | 123.9 | 56.0 | 55 | 43.9 | 76.6 | 51.8 | |

| Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 live births; 2013) | 500 | 400 | 420 | 380 | 560 | 440 | 320 | 140 | 360 | 410 | |

| Deaths due to HIV/AIDS (per 1000 population; both sexes; all ages; 2013) | 11 (per 100 000 population) | 5.8 | 45.0 | 10.0 | 2.3 | 5.5 | 1.8 | 200 | 3.1 | 78 | |

| Deaths due to malaria (per 100 000 population; both sexes; all ages; 2010) | 71.55 | 191.0 | 4.0 | 52.0 | 108.0 | 16.0 | 44.0 | 0.2 | NA | 34.0 | |

| Healthcare infrastructure | Hospital density (per 100 000 population; both sexes; all ages; 2013) | NA | 0.31 | 0.22 | 1.36 | 56.45 | 0.47 | 0.16 | 0.67 | 1.35 | NA |

| Density of healthcare centers and health post (per 100 000 population; both sexes; all ages; 2013) | NA | 11.89 | 15.14 | 10.42 | 38.61 | 13.23 | 7.41 | 6.43 | 14.45 | NA | |

| Physician density (per 1000 population; both sexes; all ages) | NA | 0.047 (2010) | 0.025 (2009) | 0.096 (2010) | 0.07 (2009) | 0.161 (2007) | 0.059 (2008) | 0.776 (2013) | 0.28 (2008) | 0.031 (2012) | |

| Density of nurses and midwives (per 1000 population; both sexes; all ages) | NA | 0.565 (2010) | 0.253 (2009) | 0.926 (2010) | 0.585 (2009) | 0.316 (2004) | 0.42 (2008) | 5.114 (2013) | 0.84 (2008) | 0.436 (2012) | |

| Density of pharmaceutical personnel (per 1000 population; both sexes; all ages) | NA | 0.022 (2010) | 0.031 (2009) | 0.071 (2008) | 0.012 (2009) | 0.01 (2004) | 0.01 (2008) | 0.277 (2004) | 0.01 (2008) | 0.014 (2012) | |

| Density of community and traditional health workers (per 1000 population; both sexes; all ages) | NA | 0.129 (2010) | 0.364 (2009) | 0.192 (2008) | 2.917 (2004) | 0.022 (2004) | NA | 0.203 (2004) | 0.169 (2004) | NA | |

| HIV/AIDS testing and counseling facilities (per 100 000 adult population; both sexes; 2011) | NA | 19 | 4 (2010) | 11 | 7 (2010) | 13 | 14 | 20 | 1 | 18 | |

| Healthcare utilization | Antenatal care coverage (%; at least 1 visit/at least 4 visits; both sexes) | 77/48 (2007–2014) | 94.9/33.7 (2010) | 33.9/19.1 (2010–2011) | 96.4/86.6 (2011) | 92.6/67.6 (2010) | 82.1/51.1 (2012–2013) | 94.5/46.5 (2012–2013) | 97.1/87.1 (2008) | 74.3/47.1 (2010) | 87.8/42.8 (2010) |

| Measles immunization coverage among 1-y-olds (%; both sexes; 2013) | 74 | 82 | 62 | 89 | 69 | 63 | 84 | 66 | 85 | 99 | |

| DPT3 immunization coverage among 1-y-olds (%; both sexes; 2013) | 75 | 88 | 72 | 90 | 80 | 74 | 92 | 65 | 93 | 91 | |

| HepB3 immunization coverage among 1-y-olds (%; both sexes; 2013) | 76 | 88 | 72 | 90 | 76 | 74 | 92 | 65 | 93 | 91 | |

| Hib3 immunization coverage among 1-y-olds (%; both sexes; 2013) | 72 | 88 | 72 | 90 | 76 | 74 | 92 | 65 | 93 | 91 | |

| Febrile children received antimalarial treatment (%; both sexes; <5 y) | 27 (2013) | 48 (2006) | 9.5 (2007) | 24 (2008) | 45.7 (2006) | 34.2 (2004) | 22 (2006) | 65 (2010) | 50.2 (2000) | 58.2 (2005) | |

| Reported number of people receiving ART (both sexes; all ages; 2013) | 12 400 000 (2011) | 42 145 | 317 443 | 75 762 | 6913 | 519 | 13 716 | 2 623 271 | 3308 | 512 555 | |

| TB case detection rate (both sexes; all ages; 2013) | 52 | 59 | 62 | 88 | 32 | 50 | 68 | 69 | 46 | 79 | |

| Effective treatment rate of new TB cases (both sexes; all ages; 2013) | 81 | 80 | 91 | 84 | 71 | 82 | 84 | 77 | 75 | 90 | |

| Healthcare expenditures | General government expenditure on health as a percentage of total expenditure on health (%; both sexes; all ages; 2013) | 49.5 | 58.5 | 61 | 57.1 (2012) | 22.7 (2012) | 60.8 (2012) | 52.3 | 48.4 | 23.4 (2012) | 36.3 (2012) |

| Private expenditure on health as a percentage of total expenditure on health (%; both sexes; all ages; 2013) | 50.5 | 40.2 | 39 | 42.9 (2012) | 77.3 (2012) | 39.3 (2012) | 47.7 | 51.6 | 76.6 (2012) | 63.7 (2012) | |

| Out-of-pocket expenditure as a percentage of total expenditure on health (%; both sexes; all ages; 2013) | 31.7 | 33.3 | 35.4 | 28.7 (2012) | 43.2 (2012) | 31.5 (2012) | 36.9 | 7.1 | 73.7 (2012) | 33.2 (2012) | |

| Private prepaid plans as a percentage of private expenditure on health (%; both sexes; all ages; 2013) | 27.3 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 6.3 (2012) | 0.0 (2012) | 9.9 (2012) | 21.1 | 81.1 | 1.0 (2012) | 1.5 (2012) | |

| Total expenditure on health as a percentage of GDP (%; both sexes; all ages; 2013) | 5.8 | 6.4 | 5.1 | 5.2 (2012) | 5.9 (2012) | 4.1 (2012) | 4.2 | 8.9 | 7.3 (2012) | 7.3 | |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; DTP3, vaccine against diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus; GDP, gross domestic product; HDI, Human Development Index; HepB3, vaccine against hepatitis B; Hib3, vaccine against Haemophilus influenzae type b; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NA, not available; PPP, purchasing power parities; TB, tuberculosis.

a The Human Development Index is a composite index to measure average achievements in life expectancy, education, and income per capita to rank countries into very high, high, medium, and low human development.

Hence, the assessment of accessing and utilizing healthcare is an important determinant. This variable allows researchers not only to detect weaknesses of existing healthcare systems in financial schemes, disposition of resources, and barriers to entry, but also to identify nodal points for implementing preventive strategies and interventions, and to support a more accurate estimation of the disease burden within a population [5–7]. This is particularly important during studies that utilize an observational passive HCF-based surveillance design, as disease incidences are strongly influenced by substantial variations in healthcare-seeking behavior patterns [5, 8]. The avoidance of underestimating the disease burden in a population is contingent on adjustments for healthcare utilization [6, 9, 10].

The Typhoid Fever Surveillance in Africa Program (TSAP) has investigated the incidence of invasive Salmonella infections through passive, HCF- based surveillance. To assess healthcare utilization for fever among the program's study populations, a population-based, cross-sectional survey design was developed and introduced at selected sites in Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Madagascar, Senegal, South Africa, Sudan, and Tanzania. The main objective of the healthcare utilization survey was to estimate the percentage of each study population that selected a public HCF nominated for TSAP as the first point of entry into the healthcare system for a condition associated with fever. These data were then used to adjust estimates of invasive salmonellosis and other fever-related diseases for the percentage of each study population that was not captured by the program's surveillance [11].

METHODS

The survey design and data collection as well as baseline analyses are explained for the study sites in Polesgo and Nioko 2, Burkina Faso; Butajira, Ethiopia; Bissau, Guinea-Bissau; Imerintsiatosika and Isotry, Madagascar; Pikine, Senegal; Pietermaritzburg, South Africa; Wad-Medani, Sudan; and Moshi, Tanzania. All methodological differences among the sites are indicated throughout the manuscript where appropriate. The survey methodology for the study site in Asante Akim North District, Ghana (AAN) has been described previously [12]. Protocol and study procedures were approved at each participating site by the research ethics committees of all collaborating institutions and the Institutional Review Board of the International Vaccine Institute.

Study Design

Study sites were selected based on available reports on typhoid fever, a suitable laboratory infrastructure, sufficient experience in surveillance, and access to healthcare within each site [11, 13]. National health indicators for each participating country compared to the African Region are outlined in Table 1. The size of each study population and the boundaries of each site and its administrative subunits were determined using source data, including latest demographic information, administrative and geographic data, sketch-maps, and population summary figures and growth factors. In addition, contemporary admission records were accessed to trace back residences of patients seeking healthcare at a TSAP-HCF and to reconfirm the boundaries of each site. Site-specific characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Background Data and Applied Sampling Strategy by Study Site, Typhoid Fever Surveillance in Africa Program, 2011–2013

| Country | Burkina Faso |

Ethiopia | Ghana [8] | Guinea-Bissau | Madagascar |

Senegal | South Africa | Sudan | Tanzania | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subarea/Region | Ouagadougou, Kossodo District | Gurage Zone | Ashanti Region | Bissau | Arivonimamo | Antananarivo | Dakar | KwaZulu-Natal Province | Al Gezira State | Kilimanjaro Region | |

| Study site | Polesgo | Nioko 2 | Butajira | Asante Akim North District | Suburbs of Bissau | Imerintsiatosika | Isotry | Pikine District | Pietermaritzburg | Wad- Medani | Moshi Urban District and Rural District |

| Settinga | Semiurban | Urban | Rural | Rural | Urban | Rural | Urban | Urban/ Semiurban | Semiurban | Semiurban | Semiurban/ Rural |

| Study population | 5738 (2012)b | 13 846 (2012)b | 62 000 (2012)b | 170 000 | 100 000 (2012)b | 46 381 (2011) [14] | 65 622 (2011) [14] | 360 000 (2012) [15] | 361 582 (2011) [16] | 48 000 (2012) [17] | 651 029 (2012) [18] |

| Approximate study area, km2 | <2 | 8 | 797 | 1160 | 16 | 182 | 2 | 8 | 343 | 6 | 1458 |

| No. of study area's subunitsc | 4 | 7 | 10 | 138 | 30 | 36 | 14 | 6 | 22 | 10 | 30 |

| Sampling frame | Existingb | Existingb | Existingb | Existing | Existingb | Generated | Generated | Generated | Generated | Generated | Not available |

| Random sampling procedure | Simple | Weighted- Stratified | Weighted- Stratified | Weighted- Stratified | Weighted- Stratified | Weighted- Stratified | Weighted- Stratified | Weighted- Stratified | Weighted- Stratified | Weighted- Stratified | Stratified-Systematic |

| Period of survey conduct | July–August 2012 | July–August 2012 | March 2013 | March–September 2008 | May–December 2012 | August 2012 | August 2012 | September 2012–January 2013 | September–December 2013 | August–September 2013 | June–July 2011 |

a Characterization of each setting as known locally.

b Population data and sampling frame obtained from the Health and Demographic Surveillance System database of the International Network for the Demographic Evaluation of Populations and Their Health (INDEPTH) [19].

c Study area's subunits that were covered by the healthcare utilization survey; subunits are based on administrative and/or geographical subdivision.

The survey was conducted at randomly selected households. For the purpose of this survey, a household was defined as a person or persons sharing housekeeping arrangements, acknowledging an adult person as the household head, and providing themselves with essentials for living. For enrollment into the survey, we determined that household members had been residents in the identified household for at least 6 months prior to being approached and provided voluntarily written fully informed consent. Eligible household members were females and males of all ages. Individuals with unknown residence, those with residence outside the study area, and temporary visitors were excluded.

The sampling frame, which listed all households in a study area, was utilized for random selection of households using a simple or stratified or weighted-stratified random sampling methodology (Table 2). It preexisted for Polesgo/Nioko 2, Butajira, and Bissau, and was extracted from a Health and Demographic Surveillance System database [19]. No sampling frame was available for Pikine, Wad-Medani, Pietermaritzburg, and Imerintsiatosika/Isotry; at these sites, the frame was generated using satellite imageries [20, 21] (eg, Google Earth Pro, Google Inc, Mountain View, California) to enumerate structures, hypothesizing that a structure constitutes the residence of a single household. Neither did a sampling frame exist for Moshi, nor could it be generated. Therefore, a central location in each subunit and a direction pointing toward the subunit's boundaries followed by a starting household and households in closest proximity were selected, applying systematic sampling.

The minimum sample size per site was computed assuming a proportion (defined as the study area's population that sought healthcare for fever at a TSAP-HCF) of 0.2 (Moshi: 0.05) within 95% confidence intervals (CIs) (Moshi: 98.8% CI), a normal deviate for an α error of 0.05 (Moshi: 0.0125), a precision of 5.0%, and a design effect of 2.0 [22, 23]. A design effect of 2.0 was assumed (exception: Polesgo) as no reliable estimates were available [24, 25] and to adjust for healthcare utilization patterns clustering naturally among household members [22]. The sample size calculation resulted in a minimum of 246 (Polesgo), 492 (Nioko 2, Butajira, Bissau, Imerintsiatosika/Isotry, Pikine, Pietermaritzburg, Wad-Medani), and 779 (Moshi) households to be visited. The sample size was further weighted proportionally to the population size of each study area's subunit (exception: Polesgo and Moshi). Microsoft Visual FoxPro's (Redmond, Washington) random number generator selected households without replacement (exception: Moshi).

Data Collection

On-site interviewers were identified and underwent training just before the survey start on locating of households, identification of respondents, informed consent procedures, and deployment of the pretested standardized survey questionnaire. Informed consent forms and questionnaires were translated into Amharic, Arabic, French, Portuguese, and Swahili, and back-translated into English to identify translation errors and to make corrections. For the purpose of this study, a respondent was defined as an adult, permanent household member, and decision maker concerning healthcare utilization for the entire household and served, thus, as a proxy for the entire household. Eligibility of the respondent was assessed at each household. Appointments for up to 3 consecutive visits were made if an eligible respondent was not present. Fever was self-diagnosed and lasted <3 days, in conformity with the study inclusion criteria as defined for TSAP [11].

The customized survey questionnaire aimed at collecting primarily background and demographic data and the overall as well as age-stratified healthcare-seeking behavior. Main background and demographic data were the household's address and geographic positioning system coordinates, the respondent's identification, and the number of household members, including each member's age and sex. Primary data for assessing healthcare utilization were the first choice of healthcare in cases of fever. Predefined categories for assessing choices of healthcare were visiting a public TSAP-HCF (eg, hospital, healthcare center, health post; for types of HCF by site, see Table 3) or any private or public HCF, or consulting a medical practitioner, pharmacy, or traditional healer in the study area. Further categories included self-management (someone decides autonomously for himself/herself or other members of the same household how to treat fever without consulting a health professional) or not treating fever at all.

Table 3.

Age-Stratified Healthcare-Seeking Behavior for Fever Lasting <3 Days for Predefined Healthcare Utilization Categories by Study Site, Typhoid Fever Surveillance in Africa Program, 2011–2013

| Healthcare Utilization Option | Age Group |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <2 y |

2 to <5 y |

5 to <15 y |

≥15 y |

|||||

| Crude Percentage | 95% CI | Crude Percentage | 95% CI | Crude Percentage | 95% CI | Crude Percentage | 95% CI | |

| Polesgo, Burkina Fasoa | ||||||||

| CSPS Polesgo (HC)b | 92.65 (63/68) | 91.14–94.16 | 83.59 (107/128) | 81.45–85.74 | 87.50 (238/272) | 85.58–89.42 | 88.48 (599/677) | 86.63–90.33 |

| Self-management | 0.00 (0/68) | .00–.00 | 0.78 (1/128) | .27–1.29 | 0.00 (0/272) | .00–.00 | 0.59 (4/677) | .15–1.03 |

| Traditional healer | 0.00 (0/68) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/128) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/272) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/677) | .00–.00 |

| HCFc | 7.35 (5/68) | 5.84–8.86 | 15.63 (20/128) | 13.52–17.73 | 12.50 (34/272) | 10.58–14.42 | 10.93 (74/677) | 9.12–12.74 |

| Nothing | 0.00 (0/68) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/128) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/272) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/677) | .00–.00 |

| Nioko, Burkina Fasoa | ||||||||

| CMA Kossodo (H)b | 81.06 (107/132) | 79.44–82.68 | 81.17 (181/223) | 79.55–82.79 | 80.53 (484/601) | 78.89–82.17 | 81.05 (1039/1282) | 79.42–82.67 |

| Self-management | 11.36 (15/132) | 10.05–12.68 | 15.25 (34/223) | 13.76–16.74 | 15.14 (91/601) | 13.66–16.63 | 14.82 (190/1282) | 13.35–16.29 |

| Traditional healer | 1.52 (2/132) | 1.01–2.02 | 0.45 (1/223) | .86–1.81 | 1.33 (8/601) | .00–.00 | 1.17 (15/1282) | .72–1.62 |

| HCFc | 6.06 (8/132) | 5.07–7.05 | 3.14 (7/223) | 2.42–3.86 | 4.33 (26/601) | 3.48–5.17 | 2.89 (37/1282) | 2.19–3.58 |

| Nothing | 0.00 (0/132) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/223) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/601) | .00–.00 | 0.08 (1/1282) | -.04–.19 |

| Butajira, Ethiopiad | ||||||||

| Butajira Hospital (H)b | 21.74 (25/115) | 20.15–23.33 | 22.92 (55/240) | 21.30–24.54 | 25.63 (203/792) | 23.95–27.31 | 28.90 (417/1443) | 27.15–30.64 |

| Butajira Health Center (HC)b | 23.48 (27/115) | 21.85–25.11 | 18.33 (44/240) | 16.84–19.82 | 19.95 (158/792) | 18.41–21.49 | 19.13 (276/1443) | 17.61–20.64 |

| Enseno Health Center (HC)b | 15.65 (18/115) | 14.25–17.05 | 13.75 (33/240) | 12.42–15.08 | 10.98 (87/792) | 9.78–12.19 | 10.95 (158/1443) | 9.75–12.15 |

| (Shershera) Bido Health Center (HC)b | 8.70 (10/115) | 7.61–9.78 | 5.42 (13/240) | 4.54–6.29 | 6.82 (54/792) | 5.85–7.79 | 4.02 (58/1443) | 3.26–4.78 |

| Self-management | 3.48 (4/115) | 2.77–4.18 | 3.75 (9/240) | 3.02–4.48 | 2.65 (21/792) | 2.03–3.27 | 2.84 (41/1443) | 2.20–3.48 |

| Traditional healer | 0.00 (0/115) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/240) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/792) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/1443) | .00–.00 |

| Pharmacy | 0.00 (0/115) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/240) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/792) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/1443) | .00–.00 |

| HCFc | 26.96 (31/115) | 25.25–28.67 | 35.42 (85/240) | 33.57–37.26 | 33.46 (265/792) | 31.64–35.28 | 34.03 (491/1443) | 32.20–35.85 |

| Nothing | 0.00 (0/115) | .00–.00 | 0.42 (1/240) | .17–.66 | 0.51 (4/792) | .23–.78 | 0.14 (2/1443) | .00–.28 |

| Bissau, Guinea-Bissaud,e | ||||||||

| Hospital Nacional Simão Mendes (H)b | 16.85 (28/165) | 15.67–18.02 | 18.01 (50/279) | 16.80–19.22 | 20.93 (164/782) | 19.65–22.21 | 21.82 (580/2659) | 20.53–23.12 |

| Centro de Bandim (HC)b | 29.35 (48/165) | 27.92–30.78 | 24.52 (68/279) | 23.17–25.87 | 23.72 (185/782) | 22.38–25.06 | 23.26 (618/2659) | 21.93–24.58 |

| Self-management | 3.80 (6/165) | 3.20–4.41 | 5.75 (16/279) | 5.02–6.48 | 7.21 (56/782) | 6.40–8.02 | 6.80 (181/2659) | 6.01–7.59 |

| Traditional healer | 1.63 (3/165) | 1.23–2.03 | 0.77 (2/279) | .49–1.04 | 0.47 (4/782) | .25–.68 | 0.89 (24/2659) | .60–1.19 |

| Pharmacy | 3.80 (6/165) | 3.20–4.41 | 3.45 (10/279) | 2.87–4.02 | 3.02 (24/782) | 2.48–3.56 | 3.58 (95/2659) | 2.99–4.16 |

| HCFc | 44.57 (74/165) | 43.00–46.13 | 47.51 (133/279) | 45.94–49.08 | 44.19 (346/782) | 42.62–45.75 | 43.47 (1156/2659) | 41.91–45.03 |

| Nothing | 0.00 (0/165) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/279) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/782) | .00–.00 | 0.18 (5/2659) | .05–.31 |

| Imerintsiatosika, Madagascar | ||||||||

| CSB II Imerintsiatosika (HC)b | 27.36 (29/106) | 25.65–29.06 | 20.94 (40/191) | 19.38–22.50 | 16.60 (118/711) | 15.17–18.02 | 16.11 (260/1614) | 14.70–17.52 |

| CSB II Isotry Central (HC)b | 1.89 (2/106) | 1.37–2.41 | 1.57 (3/191) | 1.09–2.05 | 1.55 (11/711) | 1.07–2.02 | 1.24 (20/1614) | .82–1.66 |

| Self-management | 15.09 (16/106) | 13.72–16.46 | 19.37 (37/191) | 17.86–20.88 | 16.60 (118/711) | 15.17–18.02 | 17.22 (278/1614) | 15.78–18.67 |

| Traditional healer | 5.66 (6/106) | 4.78–6.54 | 3.66 (7/191) | 2.95–4.38 | 2.95 (21/711) | 2.31–3.60 | 2.85 (46/1614) | 2.21–3.49 |

| Medical practitioner | 4.72 (5/106) | 3.91–5.53 | 4.19 (8/191) | 3.42–4.96 | 6.33 (45/711) | 5.40–7.26 | 8.18 (132/1614) | 7.13–9.23 |

| Pharmacy | 30.19 (32/106) | 28.43–31.95 | 32.98 (63/191) | 31.18–34.78 | 40.65 (289/711) | 38.77–42.53 | 39.59 (639/1614) | 37.72–41.46 |

| HCFc | 13.21 (14/106) | 11.91–14.50 | 13.61 (26/191) | 12.30–14.93 | 12.52 (89/711) | 11.25–13.78 | 12.27 (198/1614) | 11.01–13.52 |

| Nothing | 1.89 (2/106) | 1.37–2.41 | 3.66 (7/191) | 2.95–4.38 | 2.81 (20/711) | 2.18–3.45 | 2.54 (41/1614) | 1.94–3.14 |

| Isotry, Madagascar | ||||||||

| CSB II Imerintsiatosika (HC)b | 0.00 (0/68) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/155) | .00–.00 | 0.55 (3/550) | .24–.85 | 0.46 (7/1520) | .18–.64 |

| CSB II Isotry Central (HC)b | 5.88 (4/68) | 4.92–6.85 | 10.32 (16/155) | 9.08–11.57 | 9.09 (50/550) | 7.91–10.27 | 7.70 (117/1520) | 6.61–8.71 |

| Self-management | 16.18 (11/68) | 14.67–17.68 | 12.90 (20/155) | 11.53–14.28 | 15.27 (84/550) | 13.80–16.75 | 14.61 (222/1520) | 13.16–15.99 |

| Traditional healer | 0.00 (0/68) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/155) | .00–.00 | 0.73 (4/550) | .38–1.08 | 0.39 (6/1520) | .14–.55 |

| Medical practitioner | 38.24 (26/68) | 36.25–40.22 | 25.81 (40/155) | 24.02–27.60 | 20.18 (111/550) | 18.54–21.82 | 21.51 (327/1520) | 19.83–23.15 |

| Pharmacy | 29.41 (20/68) | 27.55–31.28 | 40.00 (62/155) | 37.99–42.01 | 40.36 (222/550) | 38.36–42.37 | 42.63 (648/1520) | 40.61–44.64 |

| HCFc | 10.29 (7/68) | 9.05–11.54 | 10.97 (17/155) | 9.69–12.25 | 12.18 (67/550) | 10.84–13.52 | 10.79 (164/1520) | 9.52–11.99 |

| Nothing | 0.00 (0/68) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/155) | .00–.00 | 1.64 (9/550) | 1.12–2.16 | 1.91 (29/1520) | 1.35–2.38 |

| Pikine, Senegal | ||||||||

| Centre de Santé Dominique (HC)b | 24.74 (47/190) | 23.50–25.98 | 25.38 (118/465) | 24.13–26.63 | 17.95 (179/997) | 16.85–19.06 | 19.85 (597/3007) | 18.71–21.00 |

| Dispensaire IPS (HP)b | 0.00 (0/190) | .00–.00 | 1.72 (8/465) | 1.35–2.09 | 0.80 (8/997) | .55–1.06 | 0.30 (9/3007) | .14–.46 |

| Dispensaire Deggo (HP)b | 8.95 (17/190) | 8.13–9.77 | 8.39 (39/465) | 7.59–9.18 | 7.52 (75/997) | 6.77–8.28 | 5.49 (165/3007) | 4.83–6.14 |

| Dispensaire Santa Yalla (HP)b | 4.21 (8/190) | 3.63–4.79 | 1.94 (9/465) | 1.54–2.33 | 2.91 (29/997) | 2.43–3.39 | 2.46 (74/3007) | 2.02–2.91 |

| Dispensaire Guinaw Rail Sud (HP)b | 1.05 (2/190) | .76–1.35 | 1.08 (5/465) | .78–1.37 | 2.71 (27/997) | 2.24–3.17 | 1.90 (57/3007) | 1.50–2.29 |

| Self-management | 0.53 (1/190) | .32–.73 | 1.72 (8/465) | 1.35–2.09 | 2.01 (20/997) | 1.60–2.41 | 2.89 (87/3007) | 2.41–3.37 |

| Traditional healer | 0.53 (1/190) | .32–.73 | 0.22 (1/465) | .08–.35 | 0.10 (1/997) | .01–.19 | 0.13 (4/3007) | .03–.24 |

| Medical practitioner | 7.89 (15/190) | 7.12–8.67 | 6.24 (29/465) | 5.54–6.93 | 5.22 (52/997) | 4.58–5.85 | 4.76 (143/3007) | 4.14–5.37 |

| Pharmacy | 16.84 (32/190) | 15.77–17.92 | 18.06 (84/465) | 16.96–19.17 | 18.86 (188/997) | 17.73–19.98 | 19.69 (592/3007) | 18.55–20.83 |

| HCFc | 31.58 (60/190) | 30.24–32.91 | 29.46 (137/465) | 28.15–30.77 | 32.10 (320/997) | 30.76–33.44 | 32.62 (981/3007) | 31.28–33.97 |

| Nothing | 3.68 (7/190) | 3.14–4.23 | 5.81 (27/465) | 5.13–6.48 | 9.83 (98/997) | 8.97–10.68 | 9.91 (298/3007) | 9.05–10.77 |

| Pietermaritzburg, South Africa | ||||||||

| Edendale Hospital (H)b | 2.11 (2/95) | 1.58–2.64 | 1.71 (2/117) | 1.23–2.19 | 3.24 (19/587) | 2.58–3.89 | 31.88 (644/2020) | 30.16–33.60 |

| Self-management | 9.47 (9/95) | 8.39–10.55 | 12.82 (15/117) | 11.59–14.05 | 6.30 (37/587) | 5.41–7.20 | 1.04 (21/2020) | .67–1.41 |

| Traditional healer | 0.00 (0/95) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/117) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/587) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/2020) | .00–.00 |

| Medical practitioner | 2.11 (2/95) | 1.58–2.64 | 5.13 (6/117) | 4.31–5.94 | 5.28 (31/587) | 4.46–6.11 | 8.17 (165/2020) | 7.16–9.18 |

| Pharmacy | 4.21 (4/95) | 3.47–4.95 | 4.27 (5/117) | 3.53–5.02 | 5.45 (32/587) | 4.61–6.29 | 1.34 (27/2020) | .91–1.76 |

| HCFc | 77.89 (74/95) | 76.36–79.43 | 73.50 (86/117) | 71.88–75.13 | 77.51 (455/587) | 75.97–79.05 | 56.98 (1151/2020) | 55.15–58.81 |

| Nothing | 4.21 (4/95) | 3.47–4.95 | 2.56 (3/117) | 1.98–3.15 | 1.87 (11/587) | 1.37–2.37 | 0.45 (9/2020) | .20–.69 |

| Wad Medani, Sudan | ||||||||

| Gezirtelfil (HC)b | 6.98 (6/86) | 6.09–7.86 | 13.16 (20/152) | 11.98–14.33 | 10.56 (64/606) | 9.49–11.63 | 13.21 (305/2325) | 11.94–14.29 |

| Dardig (HC)b | 1.16 (1/86) | .79–1.54 | 4.61 (7/152) | 3.88–5.34 | 3.14 (19/606) | 2.53–3.74 | 3.44 (80/2325) | 2.81–4.08 |

| Abusnoon (HC)b | 13.95 (12/86) | 12.75–15.16 | 5.26 (8/152) | 4.49–6.04 | 9.57 (58/606) | 8.55–10.60 | 12.09 (281/2325) | 10.95–13.22 |

| Self-management | 16.28 (14/86) | 14.99–17.56 | 21.71 (33/152) | 20.28–23.15 | 28.71 (174/606) | 27.14–30.29 | 32.52 (756/2325) | 30.89–34.15 |

| Traditional healer | 2.33 (2/86) | 1.80–2.85 | 2.63 (4/152) | 2.07–3.19 | 4.62 (28/606) | 3.89–5.35 | 5.59 (130/2325) | 4.79–6.39 |

| Medical practitioner | 1.16 (1/86) | .79–1.54 | 1.32 (2/152) | .92–1.71 | 1.65 (10/606) | 1.21–2.09 | 1.38 (32/2325) | .97–1.78 |

| Pharmacy | 0.00 (0/86) | .00–.00 | 0.66 (1/152) | .38–.94 | 0.99 (6/606) | .65–1.33 | 0.69 (16/2325) | .40–.98 |

| HCFc | 58.14 (50/86) | 56.42–59.86 | 50.00 (76/152) | 48.26–51.74 | 39.93 (242/606) | 38.23–41.64 | 30.32 (705/2325) | 28.72–31.92 |

| Nothing | 0.00 (0/86) | .00–.00 | 0.66 (1/152) | .38–.94 | 0.83 (5/606) | .51–1.14 | 0.86 (20/2325) | .54–1.18 |

| Moshi, Tanzaniaa,f | ||||||||

| Mawenzi Hospital (H)b | 4.65 (2/43) | 3.91m–5.39 | 1.10 (2/182) | .73–1.47 | 12.98 (85/655) | 11.79–14.16 | 1.72 (38/2209) | 1.26–2.18 |

| Self-management | 62.79 (27/43) | 61.09–64.50 | 73.08 (133/182) | 71.51–74.64 | 9.92 (65/655) | 8.87–10.98 | 79.00 (1745/2209) | 77.56–80.43 |

| Traditional healer | 0.00 (0/43) | .00–.00 | 0.55 (1/182) | .29–.81 | 16.95 (111/655) | 15.62–18.27 | 8.37 (185/2209) | 7.40–9.35 |

| HCFc | 32.56 (14/43) | 30.91–34.21 | 25.27 (46/182) | 23.74–26.81 | 50.69 (332/655) | 48.92–52.45 | 10.37 (229/2209) | 9.29–11.44 |

| Nothing | 0.00 (0/43) | .00–.00 | 0.00 (0/182) | .00–.00 | 9.47 (62/655) | 8.43–10.50 | 0.50 (11/2209) | .25–.75 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CMA, Centres Médicaux avec Antennes chirurgicales; CSB, Centres Santé de Bases; CSPS, Centre de Santé et de Promotion Social; H, hospital; HC, healthcare center; HCF, healthcare facility; HP, health post; IPS, Institut de Pédiatrie; TSAP, Typhoid Fever Surveillance in Africa Program.

a Medical practitioner and pharmacy not assessed.

b Public HCF nominated for TSAP.

c Public or private HCF not nominated for TSAP.

d Medical practitioner not assessed.

e Age groups: 0–1 year, 2–4 years, >5–14 years, and >14 years.

f Age groups: <1 year, 1–5 years, >5–15 years, and >15 years.

Data Analyses

Relative frequencies, ratios, or arithmetic means were computed for the variable distributions, including 95% CI (normal approximation), using Stata software, version 11 (College Station, Texas). The percentage of each study population (both sexes; all ages, <2 years, 2 to <5 years, 5 to <15 years, ≥15 years) that chose a TSAP-HCF as primary location in the event of fever was computed, including 95% CI (application of overall and age-stratified percentages; see Marks et al [11]).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

We interviewed a total of 28 509 people in 5359 households (AAN: 8715 [12]). The household head (acknowledged by household members) was interviewed in about 50% of enrolled households, except for Pikine (27.1%) and Wad-Medani (22.1%). Respondents were mainly female (range of male-female sex ratio, 0.30–0.85; AAN, 99.2% [12]) and had a mean age ranging from 34 years (95% CI, 33.3–35.6 years; Nioko 2) to 49 years (95% CI, 47.7–50.0 years; Moshi).

Absolute sizes of surveyed populations among all enrolled households varied: <2000 people in Polesgo; 2000–3000 people in Nioko 2, Butajira, Pietermaritzburg, and Imerintsiatosika/Isotry; 3000–4000 people in Wad-Medani, Bissau, and Moshi; and >4000 people in Pikine-Senegal. The household sizes (indicated as mean number of household members) were largest in Bissau (mean, 8 [95% CI, 7.6–8.3]) and Pikine (mean, 8 [95% CI, 7.5–8.2]) and smallest in Moshi (mean, 4 [95% CI, 3.7–3.9]). The studied populations had an almost equal male-female sex ratio in Nioko 2, Butajira, Wad-Medani, and Imerintsiatosika (range, 1.00–1.07) compared with a slightly smaller male-female sex ratio (range, 0.82–0.92) among all other study populations. All surveyed populations had a similar age distribution (<15 years of age: 30%–40%; ≥15 years of age: 60%–70%).

Overall Healthcare-Seeking Behavior

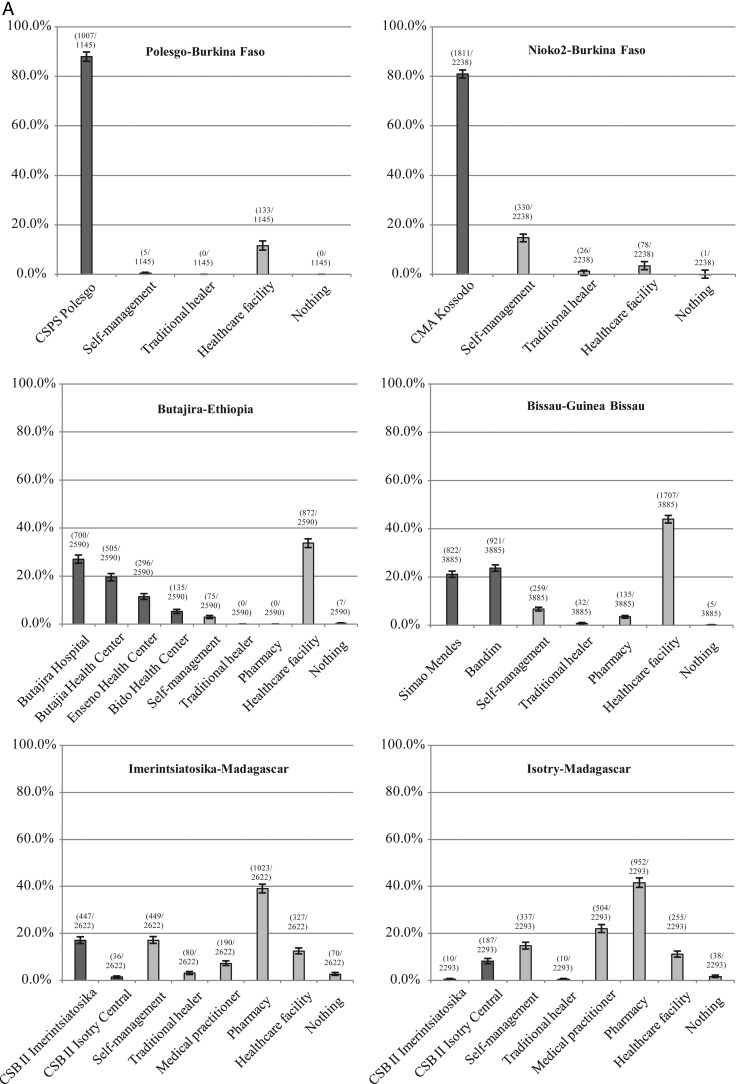

Studied populations revealed an overall tendency of either seeking healthcare predominantly at HCFs, or at HCFs and, alternatively, primarily at pharmacies or medical practitioners in the same study area or deciding for self-management (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A and B, Utilization of healthcare for fever lasting <3 days by study site, Typhoid Fever Surveillance in Africa Program (TSAP), 2011–2013. The horizontal axis represents precategorized healthcare utilization options. Dark gray columns, healthcare utilization at public TSAP-healthcare facilities; light gray columns, healthcare utilization at other public or private healthcare facilities, and alternative options (eg, self-management, traditional healer, medical practitioner, pharmacy, nothing). The vertical axis represents crude percentages for utilizing healthcare among the interviewed study populations of all ages and both sexes in the event of fever lasting <3 days. 95% confidence intervals are indicated by error bars and raw figures above each respective column. Abbreviations: CMA, Centres Médicaux avec Antennes chirurgicales; CSB, Centres Santé de Bases; CSPS, Centre de Santé et de Promotion Social; IPS, Institut de Pédiatrie sociale de Pikine.

More than 85% of study populations in Nioko 2, Bissau, and Pietermaritzburg, and >95% in Polesgo and Butajira reported to seek healthcare at any HCF within each study site. Among the same populations, 80.9% (1811/2238) in Nioko 2, 44.9% (1743/3885) in Bissau, 23.7% (667/2819) in Pietermaritzburg, 88.0% (1007/1145) in Polesgo, and 63.2% (1636/2590) in Butajira reported visits to any TSAP-HCF to treat fever.

More than 60% of interviewed populations in Pikine and Wad-Medani, >30% in AAN (study population: <12 years of age; results reflect only hospital attendance [12]), and 20%–30% in Imerintsiatosika/Isotry and Moshi stated utilization of any HCF. However, among these populations, only 31.6% (1473/4659) in Pikine, 27.2% (861/3169) in Wad-Medani, 18.4% (483/2622) in Imerintsiatosika, 8.6% (197/2293) in Isotry, and 4.1% (127/3089) in Moshi sought healthcare at a TSAP-HCF.

About 27.0% of the Pikine population indicated to alternatively visit medical practitioners or pharmacies or to decide for self-management, and an additional 9.2% of respondents reported not to treat fever at all. Unlike in Pikine, 38.2% of Wad-Medani's study population stated to preferably treat fever by self-management, in addition to consulting traditional healers. We found that 39.0% of the Imerintsiatosika population indicated seeking healthcare at pharmacies, whereas the remainder reported treating fever by visiting traditional healers or medical practitioners or by any mode of self-management. Healthcare-seeking patterns in Isotry were similar to those of Imerintsiatosika: 41.5% of the study population preferably consulted pharmacies. The remainder stated to visit medical practitioners or to treat fever by self-management. Unlike all other sites, >64% of Moshi's population reported favoring self-management of fever in addition to seeking healthcare from traditional healers or not treating fever at all.

Age-Stratified Healthcare-Seeking Behavior

Seeking healthcare at any HCF among age-stratified study populations revealed either no age-dependent variation or an increase or a decrease of healthcare utilization with increasing age or fluctuating healthcare utilization with increasing age. Age-stratified healthcare-seeking behavior patterns for alternative healthcare options (eg, traditional healer, medical practitioner, pharmacy, self-management, nontreatment) are summarized in Table 3.

No differences in healthcare-seeking patterns at HCFs associated with age were seen among study populations in Polesgo, Butajira, Bissau, or Isotry. However, within the same populations, the overall percentage of utilizing any TSAP-HCF in the event of fever decreased with increasing age in Polesgo, Butajira (<2 years: 69.6%; ≥15 years: 63.0%), fluctuated by age in Isotry, and did not show major age-dependent variations in Bissau. Our data additionally revealed that a larger percentage of Butajira's and Bissau's populations of increasing age utilized a TSAP hospital rather than a TSAP healthcare center (Table 3). In turn, caretakers of febrile children in Butajira and Bissau preferably visited a TSAP healthcare center rather than a TSAP hospital.

Healthcare utilization at HCFs in each study area increased with age among the Pietermaritzburg population, and decreased with increasing age of populations in Nioko 2, Imerintsiatosika, Pikine, and Wad-Medani. The same age-dependent patterns for utilizing any TSAP-HCF were also found for Pietermaritzburg (<2 years: 2.1%; ≥15 years: 31.9%), Imerintsiatosika, and Pikine (<2 years: 39.0%; ≥15 years: 30.0%). Nioko 2's study population did not indicate any age-related variations for utilizing a TSAP-HCF for fever, and Wad-Medani's population were shown to rather seek healthcare at any TSAP-HCF with increasing age (<2 years: 22.1%; ≥15 years: 28.7%). Healthcare-seeking patterns for fever fluctuated solely among age groups of the Moshi population for utilizing any HCF (<2 years: 37.2%; 2 to <5 years: 26.4%; 5 to <15 years: 63.7%; ≥15 years: 12.1%) and the TSAP-HCF.

DISCUSSION

This study revealed similarities, but also substantial differences in healthcare-seeking behavior patterns for fever as reported by well-defined proxy respondents among the study populations in the different countries. Overall findings show that more than two-thirds of the population of Polesgo and Nioko 2 (Burkina Faso) and Butajira (Ethiopia) would have been captured by the program's facility-based surveillance. In contrast, only approximately 25%–45% of study populations in Bissau (Guinea-Bissau), Pikine (Senegal), Wad-Medani (Sudan), and Pietermaritzburg (South Africa), and about 4%–20% in Imerintsiatosika and Isotry (Madagascar) and Moshi (Tanzania), would have been under optimum fever surveillance. These findings emphasize the importance of assessing facility-based healthcare utilization to generate adjusted, more accurate estimates of the occurrence of Salmonella infections and other diseases associated with fever [5, 6, 8].

The high attendance of populations in Polesgo and Nioko 2 at TSAP-HCFs may partially be explained by the encouragement of the Ministry of Health to seek formal healthcare for fever conditions [26]. Previous findings have also indicated that increased healthcare utilization at an HCF was strongly influenced by a short distance between households and the HCF [26]. This may also apply to Polesgo and Nioko 2, considering the small area of each study region. Apart from improvements in the healthcare infrastructure across Ethiopia, strong trust in modern healthcare among Ethiopians was reported by Mebratie et al [27]. In that study, attendance at HCFs for fever-associated diseases was found to be >60% [27], which is in accordance with our results. Country-wide similarities among Burkina Faso and Ethiopia in terms of the population's percentage living on <$1.25 per day, the proportion of governmental and private health expenditures, and the large number of confirmed malaria cases (Table 1) may provide additional explanations for the reported healthcare utilization.

Although Madagascar's government introduced an equity funds system for improving universal access to public healthcare, particularly for the poorest [28], Littrell et al [29] reported that healthcare was still mainly sought within Madagascar's private healthcare sector. This may provide some rationale for the large proportion missed by the program's system and indicates the need for improvement [30]. It was observed that 52% of the Madagasy population sought healthcare for fever at private pharmacies/drug shops, 26% at healthcare facilities, and 35% at other private sectors [29] (eg, medical practitioners). This is consistent with our results among children and adults in Imerintsiatosika and Isotry, Madagascar. Previous findings from Tanzania revealed that the individual perception of fever [31] as a normal condition was a common reason for not seeking healthcare at a HCF (although public healthcare for children <5 years old and pregnant women is free of charge). The preferred mode was to consult a traditional healer, not seeking healthcare at all [32], or any mode of self-management such as using one's own medicine and home remedies [33], which is in accordance with our results from Moshi. Previous investigations have shown that HCF attendance declined with increasing household sizes and distances to an HCF [32], but also due to the lack of financial affordability and trust in formal healthcare [31]. The large proportion of the population living on <$1.25 per day and the low proportion of governmental, but high proportion of private health expenditures (Table 1) may also influence healthcare-seeking patterns in Tanzania.

We tried to limit the possibility of recall bias in assessing healthcare utilization by not linking fever to a specific disease onset date and by carefully identifying respondents. Bias in selecting households was minimized by relying on the computerized random selection. A major limitation of this work was the cross-sectional study design itself—the assessment of healthcare utilization at a single time point only [5]. This allows neither for investigating secular and seasonal trends that may affect utilizing healthcare, nor for measuring potential effects of population movements [9]. Not assessing healthcare-related expenditures at households was a further weakness, but experiences gained during pretesting phases revealed the tendency of high refusal regarding questions on monetary earning and spending.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study has shown similarities and variations in healthcare-seeking behavior for conditions associated with fever. It also outlined the need to adequately capture study populations during passive facility-based surveillance, which is, hence, contingent on the assessment of patterns in healthcare utilization. However, current findings require further in-depth analyses, which could identify potential correlations between utilizing healthcare and socioeconomic characteristics, ethnographic factors, and travel distances between households and TSAP-HCFs, especially in large study areas. Furthermore, considering the existing healthcare infrastructures may help to identify nodal points for improvement of healthcare systems, and for the implementation of health promotion and education programs besides preventive measures and interventions. This in turn would support the United Nations Millennium Development Goals of improving access to healthcare and affordable medication, thereby reducing the spread of important diseases and mortality.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank Soo-Young Kwon and Hyonjin Jeon for supporting TSAP in administrative matters. We are grateful for the participation of interviewees at each of the sites in Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Madagascar, Senegal, South Africa, Sudan, and Tanzania in this study. We thank the data managers and field workers of the University of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso; the Armauer Hansen Research Institute and INDEPTH, Ethiopia; the Kumasi Centre for Collaborative Research in Tropical Medicine, Ghana; the Bandim Health Project, Guinea-Bissau; the University of Antananarivo, Madagascar; the Institute Pasteur de Dakar, Senegal; the National Institute for Communicable Diseases and the South Africa Red Cross, South Africa; the University of Gezira, Sudan; and the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre, Tanzania for their exceptional efforts and contributions, which made this research possible.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Financial support. This research was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (OPPGH5231). The International Vaccine Institute acknowledges its donors, including the Republic of Korea and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. Research infrastructure at the Moshi site was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (R01TW009237; U01 AI062563; R24 TW007988; D43 PA-03-018; U01 AI069484; U01 AI067854; P30 AI064518), and by the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/J010367). S. B. is a Sir Henry Dale Fellow, jointly funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society (100087/Z/12/Z). This publication was made possible through a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1129380).

Supplement sponsorship. This article appears as part of the supplement “Typhoid Fever Surveillance in Africa Program (TSAP),” sponsored by the International Vaccine Institute.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No potential conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.United Nations. Millennium Development Goals and beyond 2015. Available at: http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/. Accessed 10 August 2015.

- 2.World Health Organization. Global health observatory data repository 2015. Available at: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.resources. Accessed 20 August 2015.

- 3.United Nations Development Program. Human development reports. Available at: http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi. Accessed 20 August 2015.

- 4.World Bank Group. The World Bank 2015. Available at: http://www.worldbank.org/. Accessed 20 August 2015.

- 5.Bigogo G, Audi A, Aura B, Aol G, Breiman RF, Feikin DR. Health-seeking patterns among participants of population-based morbidity surveillance in rural western Kenya: implications for calculating disease rates. Int J Infect Dis 2010; 14:e967–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burton DC, Flannery B, Onyango B et al. Healthcare-seeking behaviour for common infectious disease-related illnesses in rural Kenya: a community-based house-to-house survey. J Health Popul Nutr 2011; 29:61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Investing in health for Africa: the case for strengthening systems for better health outcomes. 2011.

- 8.Jordan HT, Prapasiri P, Areerat P et al. A comparison of population-based pneumonia surveillance and health-seeking behavior in two provinces in rural Thailand. Int J Infect Dis 2009; 13:355–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nasrin D, Wu Y, Blackwelder WC et al. Health care seeking for childhood diarrhea in developing countries: evidence from seven sites in Africa and Asia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013; 89(1 suppl):3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breiman RF, Olack B, Shultz A et al. Healthcare-use for major infectious disease syndromes in an informal settlement in Nairobi, Kenya. J Health Popul Nutr 2011; 29:123–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marks F, von Kalckreuth V, Aaby P et al. The incidence of invasive Salmonella disease in sub-Saharan Africa: a multicentre population-based surveillance study. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krumkamp R, Sarpong N, Kreuels B et al. Health care utilization and symptom severity in Ghanaian children—a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2013; 8:e80598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Kalckreuth V, Konings F, Aaby Y et al. The Typhoid Fever Surveillance in Africa Program (TSAP): clinical, diagnostic, and epidemiological methodologies. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62(suppl 1):S9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ministry of Health of Madagascar. Repartition de la population par Fokotany. 2011.

- 15.Ministry of Health of Senegal. Region medicale de Dakar, District sanitaire de Pikine. 2012.

- 16.Msunduzi Integrated Development Plan for 2012–2013 (South Africa). Msunduzi Municipality. Available at: www.msunduzi.gov.za. Accessed 15 June 2013.

- 17.University of Gezira. District Population. Department of Statistics, Population Studies Centre 2008.

- 18.Ministry of Finance of Tanzania, National Bureau of Statistics. Population and housing census. The United Republic of Tanzania, Ministry of Finance of Tanzania, National Bureau of Statistics, 2012. Available at: www.nbs.go.tz. Accessed 15 October 2014.

- 19.INDEPTH Network. Better health information for better health policy 2015. Available at: http://www.indepth-network.org/. Accessed 12 August 2015.

- 20.Moss WJ, Hamapumbu H, Kobayashi T et al. Use of remote sensing to identify spatial risk factors for malaria in a region of declining transmission: a cross-sectional and longitudinal community survey. Malar J 2011; 10:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowther SA, Curriero FC, Shields T, Ahmed S, Monze M, Moss WJ. Feasibility of satellite image-based sampling for a health survey among urban townships of Lusaka, Zambia. Trop Med Int Health 2009; 14:70–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson RH, Sundaresan T. Cluster sampling to assess immunization coverage: a review of experience with a simplified sampling method. Bull World Health Organ 1982; 60:253–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henderson RH, Davis H, Eddins DL, Foege WH. Assessment of vaccination coverage, vaccination scar rates, and smallpox scarring in five areas of West Africa. Bull World Health Organ 1973; 48:183–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katz J, Zeger SL. Estimation of design effects in cluster surveys. Ann Epidemiol 1994; 4:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bostoen K, Chalabi Z. Optimization of household survey sampling without sample frames. Int J Epidemiol 2006; 35:751–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Müller O, Traoré C, Becher H, Kouyaté B. Malaria morbidity, treatment-seeking behaviour, and mortality in a cohort of young children in rural Burkina Faso. Trop Med Int Health 2003; 8:290–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mebratie AD, Van de Poel E, Yilma Z, Abebaw D, Alemu G, Bedi AS. Healthcare-seeking behaviour in rural Ethiopia: evidence from clinical vignettes. BMJ Open 2014; 4:e004020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kashima S, Suzuki E, Okayasu T, Jean Louis R, Eboshida A, Subramanian SV. Association between proximity to a health center and early childhood mortality in Madagascar. PLoS One 2012; 7:e38370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Littrell M, Gatakaa H, Evance I et al. Monitoring fever treatment behaviour and equitable access to effective medicines in the context of initiatives to improve ACT access: baseline results and implications for programming in six African countries. Malar J 2011; 10:327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marks F, Rabehanta N, Baker S et al. A way forward for healthcare in Madagascar? Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62(suppl 1):S76–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dillip A, Hetzel MW, Gosoniu D et al. Socio-cultural factors explaining timely and appropriate use of health facilities for degedege in south-eastern Tanzania. Malar J 2009; 8:144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kassile T, Lokina R, Mujinja P, Mmbando BP. Determinants of delay in care seeking among children under five with fever in Dodoma region, central Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. Malar J 2014; 13:348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chomi EN, Mujinja PG, Enemark U, Hansen K, Kiwara AD. Health care seeking behaviour and utilisation in a multiple health insurance system: does insurance affiliation matter? Int J Equity Health 2014; 13:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]