Abstract

XR5944 is a potent anticancer drug with a novel DNA binding mode: DNA bis-intercalationg with major groove binding. XR5944 can bind the estrogen response element (ERE) sequence to block ER-ERE binding and inhibit ERα activities, which may be useful for overcoming drug resistance to currently available antiestrogen treatments. This review discusses the progress relating to the structure and function studies of specific DNA recognition of XR5944. The sites of intercalation within a native promoter sequence appear to be different from the ideal binding site and are context- and sequence- dependent. The structural information may provide insights for rational design of improved ERE-specific XR5944 derivatives, as well as of DNA bis-intercalators in general.

Keywords: Anticancer drug, DNA bis-intercalation, DNA bis-intercalation with major groove binding, NMR solution structure, XR5944 or MLN944

INTRODUCTION

DNA is a major target for mainstream drugs used in the treatment of cancer. Small molecule compounds can interact with DNA through various mechanisms, including covalent binding [1, 2], and non-covalent binding such as intercalation [3, 4], minor groove [5–7] and major groove binding [8]. The biggest issue with DNA interactive chemotherapeutics is their adverse effects due to poor selectivity. Although there has been a significant effort towards the development of targeted therapeutics such as kinase inhibitors [9], these agents are not without their issues [10]. DNA-targeted small molecule agents remain the major form of therapy for many cancers. Moreover, there is reason to believe that a therapeutic advantage remains to be gained from DNA-targeted drugs with novel mechanisms of action, improved toxicity profiles, and different spectra of anti-tumor activity.

XR5944 is a Potent Anticancer Drug with a Novel DNA Binding Mode

The bis-phenazine anticancer drug XR5944 (Fig. 1A) is a DNA-targeted compound that has reached phase I clinical trials [11]. It was originally developed as a topoisomerase inhibitor [12]. The parent compounds of XR5944, phenazine carboxamides, and the related acridine carboxamides, are dual DNA topoisomerase I/II inhibitors [13–15]. While early reports indicated that XR5944 may interfere with normal topoisomerase I and II function in vitro [16], later studies have indicated that the mechanism of XR5944 action is primarily topoisomerase-independent and is related with transcription inhibition [11, 17]. XR5944 has shown exceptional activity, both in vitro and in vivo, against human and murine tumor models; having greater potency than well-known topoisomerase inhibitors including TAS-103, topotecan and doxorubicin [16, 18]. In combination with carboplatin or doxorubicin in non-small-cell lung carcinoma, or in combination with 5-fluorouracil and irinotecan in colon cancer cell lines, XR5944 showed additive potency in vitro and in vivo [19, 20].

Fig. (1).

(A) Chemical structure of XR5944 with atom numbering. (B) The sequence and numbering of DNA hexamer d(ATGCAT)2, with the preferred DNA binding site of XR5944 shown schematically. (C) The TFF1 ERE DNA sequence with numbering. The two XR5944 binding sites are shown schematically, with the strong binding sites, the XR1-2 phenazine and the XR2-1 phenazine, indicated by darker outlined boxes, and the weak binding sites, XR1-1 and XR2-2, indicated by lighter outlined boxes. The ERE half-sites are marked with solid lines.

Novel DNA Binding Mode of XR5944, DNA Bis-Intercalation with Major Groove Binding

The exceptional biological activity of XR5944 may be related to its unique DNA binding mode and mechanism of action. The parent compounds of XR5944, phenazine carboxamides (such as XR11576), as well as the closely related acridine carboxamides (such as DACA, N-(2-(dimethylamino)ethyl)acridine-4-carboxamide), are both DNA intercalators and dual DNA topoisomerase I/II inhibitors [13–15]. Crystal structures of 9-amino-DACA/DNA complexes showed that acridine rings intercalate duplex DNA at a CpG site [21, 22]. XR5944 has been shown to bind DNA strongly [21]. Such binding in the major groove is significant since most DNA binding drugs bind in the minor groove, while proteins generally bind in the major groove [24]. For example, most transcription factors bind DNA in the major groove, using bHLH (basic region Helix-Loop-Helix), bZIP (basic region leucine zipper) or zinc-containing binding motifs. It is inherently difficult to target the DNA major groove by small molecules due to the fact that the DNA major groove is wider compared to the minor groove, which makes high affinity small molecule binding more challenging [8]. The unique binding mode of XR5944 may be responsible for its novel mechanism of action as a transcription inhibitor by disrupting major groove interactions of transcription factors.

Molecular Mechanism of XR5944 Inhibition of ERα-ERE Binding

Estrogen receptor α (ERα) binds to a DNA sequence known as the estrogen response element (ERE), 5’-AGGTCAnnnTGACCT. This consensus sequence contains two inverted repeat half-sites separated by a tri-nucleotide spacer, “nnn” [25–27]. ERα binds ERE in the major groove using two zinc-finger motifs [28]. The binding site of XR5944, (TpG):(CpA), is contained in each consensus ERE half-site. We found that XR5944 specifically blocked ERα-ERE DNA-binding and inhibited ERα-mediated transcriptional responses [29]. This novel mechanism of ER inhibition may be used to overcome common modes of resistance to current antiestrogen treatments that all target the ER protein-ligand complex with estrogen [30]. We tested the ability of XR5944 to recognize consensus EREs with varying tri-nucleotide spacers and with natural, non-consensus ERE sequences using one dimensional NMR (1D 1H NMR) titration studies. Our results demonstrated that the tri-nucleotide spacer sequence significantly modulated XR5944-ERE binding, and consequently affected XR5944 inhibition of ERα-mediated transcriptional responses [31]. Particularly, XR5944 was found to bind well to the natural ERE in the estrogen-responsive TFF1 (trefoil factor 1, previously designated PS2) gene promoter (Fig. 1C), and we determined the NMR solution structure of the 2:1 XR5944: TFF1-ERE DNA complex [32]. Interestingly, the XR5944 binding sites differ from those predicted previously and have several highly unexpected features. The complex structures explain how ERE spacer sequences affect XR5944-DNA binding. The structural information may provide insights for future structure-based rational drug design of improved XR5944 derivatives to target ERE DNA and modulate ERα-induced transcriptional activity, as well as for designing DNA bis-intercalators with major groove binding in general. This review will discuss the progress relating to the structure and function studies of DNA recognition of XR5944. Methods for these studies can be found in their respective publications [23, 29, 31, 32] and structures were analyzed using 3DNA [33].

COMPLEX STRUCTURE AND DNA RECOGNITION OF XR5944 AT 5’-TGCA, ITS IDEAL BINDING SITE [23]

XR5944 Binds d(ATGCAT)2 with High Specificity

We investigated the binding of XR5944 to a series of palindromic DNA sequences and found a strong sequence- specific binding to the DNA duplex d(ATGCAT)2 (Fig. 1B). The 1D 1H NMR titration data at pH 7 indicates that XR5944 forms a stable 1:1 complex with d(ATGCAT)2 and that the binding equilibrium is in the slow exchange range at the NMR time scale (Fig. 2A). The melting temperatures of the DNA-drug complex is increased to ~45°C from ~30°C of free DNA and the imino proton G3HN1 is detectable at 25°C in the complex whereas it is not observable at 15°C in the free DNA, implying a more stable DNA duplex upon drug binding.

Fig. (2).

(A) Binding of XR5944 with DNA hexamer d(ATGCAT)2 by NMR. DNA was titrated with XR5944 at drug equivalences from 0 (top) to 1 (bottom). With increasing concentrations of XR5944, proton peaks corresponding to the free DNA begin to disappear, while concurrently, a new set of peaks representing the DNA-drug complex protons started to emerge. The free DNA protons completely disappear at the drug equivalence of 1. (B) The expanded regions of the nonexchangeable two-dimensional NO-ESY spectra of the DNA-XR5944 complex. Top: aromatic - H2’/H2’’/methyl region. The intermolecular NOE cross-peaks between XR5944 and the DNA are labeled with asterisks and arrows (for C4H5 only). Bottom: aromatic - H1’ region. The sequential assignment pathway is shown.

NMR Structure of the 1:1 XR5944 : d(ATGCAT)2 Complex

All proton resonances of the free DNA and 1:1 XR5944/DNA complex were assigned by using 2D-NOESY, TOCSY and COSY (Fig. 2B). Many intermolecular NOE crosspeaks are observed between XR5944 and DNA in the drug-DNA complex (Figs. 2B and 3). We determined the NMR-refined structure of the 1:1 XR5944-d(ATGCAT)2 complex (PDB ID 1X95, Fig. 4). The two phenazine rings of XR5944 bis-intercalate at the two symmetric T2pG3:(C4’ pA5’) and C4pA5:(T2’pG3’) steps (Fig. 4A–C). The aminoalkyl linker of XR5944 is positioned in the major groove of the DNA duplex (Fig. 4A), with the phenazine rings parallel to the long axes of the flanking base pairs of DNA (Fig. 4D). The 2-fold symmetries of both DNA and drug are retained. The linker is positioned diagonally across the major groove, giving the drug the appearance of a backward Z when viewed from the major groove (Fig. 4A). The drug exhibits a left-handed twist in contrast to the right-handed twist of the DNA. The two central G3:C4 base pairs are pulled toward the major groove via interactions with the drug linker (Fig. 4C), making the major groove significantly shallower compared to that of the regular B-DNA. The DNA duplex is kinked by ~10° towards the minor groove. The DNA double helix of the DNA hexamer is unwound throughout the drug complex. While regular B-DNA has an average helical twist of 36° per step, the overall extent of unwinding of the DNA hexamer in the drug complex is 48°, with that of the TpG step at the intercalation site being 10° and the terminal ApT step being 13°. The kinking and unwinding of the DNA in the complex induce a broad and shallow minor groove as well when compared to the regular B-DNA.

Fig. (3).

Schematic diagram of the intermolecular NOE cross-peaks between XR5944 and its preferred DNA binding site 5’-TpG in DNA hexamer. The solid, thick dashed, and thin dashed lines indicate strong, medium, and weak intensity NOEs respectively.

Fig. (4).

(A) and (B) Representative models of the NMR-refined 1:1 XR5944 - d(ATGCAT)2 complex as seen from the (A) major groove and (B) minor groove. The rise between base pairs at the intercalation site is indicated. (C) Sequence-specific hydrogen bonds between XR5944 and the DNA binding site are shown in green dashed lines in stereo view. Nitrogen atoms are colored blue, oxygen atoms are red, phosphorus atoms are orange, and hydrogen atoms are white (XR5944 only). Carbon atoms of XR5944 are yellow and those of DNA are cyan. (D) Base-stacking interactions between XR5944 and the 5’-TpG intercalation site. Carbon atoms of DNA are green and cyan by base pair. DNA sequences are labeled.

In the intercalation pocket, the rise between two intercalated T2:A5 and G3:C4 base pairs is ~6.32 Å, much larger than the rise of perpendicular intercalation sites, as seen in anthracycline drugs [34, 35]. The central G3pC4 steps, wrapped between the two phenazine rings of XR5944, maintain relatively good base-pair conformation and hydrogen bonding interactions as observed in regular B-DNA. In contrast, conformational distortions at the intercalation site T2pG3 and C4pA5 steps are more significant, with the T2:A5’ base pairs displaying a significant large negative roll angle (−13°), propeller twist (−8°), and buckling (6°). This is consistent with the fact that the TpG:CpA steps are particularly flexible [36, 37].

Unexpected XR5944 N10 Protonation in the Complex

The XR5944 molecule adopts an unexpected conformation and side-chain orientation. The N10 of the phenazine ring of XR5944 (Fig. 1A) is protonated in the DNA complex at pH7, as observed in the NMR spectra. The carbonyl group of carboxamide forms an internal hydrogen bond to the protonated phenazine ring N10 (HN-O distance of 2.0 Å). It is interesting that the XR5944 phenazine ring is protonated at pH7, since the pKa value of the N10 is only 1.0–1.3 [38] (personal communication with Dr. William Denny, University of Auckland). This unexpected drug phenazine conformation, which could not possibly exist in the bulk solution, is clearly induced and stabilized by the microenvironment of the DNA binding pocket.

Specific DNA Recognition of XR5944 at its Preferred Binding site 5’-TGCA Involves Base-Stacking Interactions and Linker-DNA Major Groove Interactions

The phenazine chromophores of XR5944 are deeply inserted into the flanking DNA base pairs (Fig. 4D). The XR5944 phenazine A ring end inserts more deeply towards the DNA minor groove and is closer to the DNA sugar backbone, whereas the drug C ring end is positioned farther from the DNA sugar backbone and more towards the DNA major groove. At each intercalation site, the drug phenazine ring is well stacked with the central G:C base pair and the T2 (or T2’) base of the T2:A5’ (or T2’:A5) base pair (Fig. 4D). The long axis of the phenazine chromophore of XR5944 is almost completely aligned with that of the central G:C base pair. The six-member ring of the guanine G3 (or G3’) base is stacked on the drug phenazine A ring, while its base pair partner, cytosine C4’ (or C4), is stacked on the drug C ring. On the other side of intercalation pocket, the thymine T2 (or T2’) is completely stacked over the phenazine ring A, whereas the adenine A5’ (or A5) base is unstacked with the drug chromophore. In addition to a strong π-stacking interaction between the T2 base and ring A of XR5944, the electro-negative O4 group of thymine T2 positioned right above the protonated, electropositive N10 imide edge of the XR5944 phenazine chromophore, while the 5-methyl group of thymine T2, which is known to increase hydrophobic interactions and stabilize ligand binding, is stacked right over the carboxamide group of XR5944 (Fig. 4D).

The two γ-amino groups of the carboxamide aminoalkyl linker of XR5944 are protonated at pH 7 and therefore positively charged as γ-NH2(+) (Fig. 1A), which facilitate the binding of drug linker in the normally very electronegative DNA major groove. XR5944 binding dramatically changes the electrostatic distribution of the DNA major groove to a more electropositive potential [23]. As the A ring end of XR5944 is deeply inserted into the intercalating pocket and is in close proximity to the DNA sugar backbone, the site-specific interactions of the drug carboxamide aminoalkyl linker with the two central guanines, G3 and G3’, are facilitated. The two γ-amino groups of the linker are positioned very close to the O6 and N7 of the two symmetrically related guanine residues for strong hydrogen-bonding interactions. Specifically, the hydrogens of each γ-amino group is 1.7 Å from G3O6 and 2.3 Å from the G3N7, respectively, to form two potential hydrogen bonds (Fig. 4C).

The parallel base-stacking intercalation binding mode has been observed in a number of drugs [21, 22, 39, 40]. Even though the chromophore structure of XR5944 is similar to that of the acridine carboxamides such as 9-amino-DACA, the base-stacking interactions of the two drugs with DNA base pairs is somewhat different [21, 22]. The phenazine ring of XR5944 is shifted more towards the major groove side of DNA compared to the acridine ring of DACA. The long axis of the phenazine ring is almost completely aligned with that of the central G:C base pair, whereas the acridine ring in 9-amino-DACA bisects the angle between the long axes of the intercalated base pairs. In addition, the protonated conformation of the drug phenazine ring, which occurs unexpectedly in the microenvironment of the DNA, indirectly induces a favorable side-chain orientation to form a site-specific hydrogen bond interaction with the two central guanines (Fig. 4C). In contrast to the carboxamide plane of 9-amino-DACA being co-planar with the acridine chromophore, the plane of the XR5944 carboxamide group is about 15° with the phenazine plane. The amide proton HN is 2.8 Å to the N7 of guanine G3 (or G3’), and the N-H….N angle of ~160°, both of which favor a hydrogen-bond formation [41].

The favorable stacking and hydrophobic interactions at the TpG intercalation site, and the favorable hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions in the DNA major groove, may be important determinants in specific recognition of the preferred binding site 5’-TGCA by XR5944.

XR5944 BINDS ERE SEQUENCES TO INHIBIT ERα ACTIVITY

In spite of major advances in treatment over the past two decades, breast cancer, the most common cancer in women, remains a leading cause of cancer mortality. Estrogens are steroid hormones which play critical roles in the genesis, development and metastasis of breast cancer [42]. Estrogen receptor-α (ERα), a ligand-activated transcription factor is the predominant mediator of estrogen (E2) responses in breast cancer cells [43]. ERα regulates transcription of target genes through direct binding to EREs, its cognate DNA recognition sites, or by modulating other transcription factors which at which bind at alternative DNA sequences [44]. ERα binds and recognizes. Endocrine therapy, or antiestrogen treatment, by modulating ERa is the primary treatment for ERα-positive breast tumors today [45]. Antiestrogen treatments include selective ER modulators (SERMs), e.g., tamoxifen, which target the estrogen-receptor complex [46], and aromatase inhibitors (AIs), e.g., anastrazole, which inhibit E2 biosynthesis [47, 48]. Unfortunately, many ERα-positive breast tumors (~20–50%) are unresponsive to [49], or ultimately develop resistance to antiestrogen treatments [50].

The intercalation site of XR5944, (TpG):(CpA), is found in the consensus ERE, which is an inverted repeat consisting of two half-sites separated by a tri-nucleotide spacer, 5’-AGGTCAnnnTGACCT [25-27] (Fig. 5A–B). We tested the inhibition of ER-DNA binding and ER transcriptional activation by XR5944 in vitro and in cultured cells [29]. In a dose-dependent manner, XR5944 inhibited the DNA binding of both recombinant ERα protein and ERα from nuclear extracts in electrophoretic mobility shift assays. Luciferase reporter assays showed that XR5944 inhibited gene expression an ERE-containing promoter, but not from a basal promoter. In contrast, actinomycin D, an RNA polymerase inhibitor, inhibits the transcription from both promoters. XR5944 seems to have some specificity for blocking the DNA binding of ERα to the ERE sequences, as data showed that XR5944 did not inhibit the transactivation of Sp1, whose consensus DNA binding sequence is 5’-GGGGCGGGGC [29], nor did XR5944 block the binding of the transcription factor NF-κB to its consensus DNA binding site 5’-GGACTTTCC [23], neither of the DNA sequences include 5’-TG motifs. Thus, it is suggested that XR5944 is able to specifically inhibit ERα binding to its consensus DNA sequence and its subsequent activity.

Fig. (5).

(A) and (B) The ERE sequences studied for interactions with XR5944. (A) Consensus ERE sequences. (B) Natural ERE sequences with variable tri-nucleotide spacer sequences. (C)–(F) Binding of XR5944 with consensus ERE sequences containing different tri-nucleotide spacers by NMR. The tri-nt spacers tested (C) CGG, (D) AGG, (E) CTG, and (F) TTT were titrated with XR5944 at drug equivalences from 0 (bottom) to 2 (top). With increasing XR5944 concentrations, the imino proton peaks corresponding to free ERE DNAs began to disappear. Simultaneously, a new set of imino proton peaks corresponding to the ERE-drug complexes emerged in a dose-dependent fashion peaking at a drug equivalence of 2. While some imino proton peaks corresponding to the XR5944-ERE complex are located in the same region as those of the free DNA (12–13.5 ppm), some of the emerging imino peaks from the drug-DNA complex were upfield-shifted, e.g., those observed at 10–11 ppm.The imino protons of the free DNAs almost completely vanish at the drug equivalence of 2 for the DNA sequences to which XR5944 binds with high specificity, as indicated by asterisks (*) and dashed lines (—) for isolated imino proton peaks of the free DNA with CGG- and AGG-spacers.

In the consensus ERE sequence, AGGTCAnnnTGACCT, the “nnn” is known as the tri-nucleotide spacer [25]. Historically, the spacer was thought not to be involved in ERα-DNA binding. It has been recently demonstrated that the tri-nucleotide spacer can modulate both ERα-ERE binding affinity and estrogen-mediated transcriptional responses [51, 52]. We tested the binding of XR5944 to consensus ERE sequences with various tri-nucleotide spacer sequences (Fig. 5A) and to natural, non-consensus ERE sequences (Fig. 5B) using 1D 1H NMR titration studies (Fig. 5B) [31]. Our results demonstrated that the tri-nucleotide spacer sequence greatly affects XR5944 binding to EREs. Of the tested sequences, EREs containing CGG and AGG spacers bind best to XR5944, while those with TTT tri-nucleotide spacers bind worst (Fig. 5C–F). The binding stoichiometry of XR5944 with EREs is 2:1. Functional studies using consensus EREs with tri-nucleotide spacers CGG, CTG, and TTT in reporter constructs indicated that XR5944 was more effective in inhibiting the activity of CGG- than TTT-spaced EREs [31]. Therefore, XR5944 binding is correlated with its efficacy of inhibiting the ERE-mediated transactivation by ERα. In the promoters of estrogen-responsive genes, the anti-ERα effect of XR5944 depends on both ERE half-site composition and the tri-nucleotide spacer sequence of EREs.

A major mechanism of de novo or acquired resistance to antiestrogen therapy involves estrogen-independent ERα receptor activation that still requires ERα-ERE binding to control the expression of estrogen-regulated target genes [53, 54]. A small molecule that binds ERE DNA, occupies the ERα binding site, and inhibits ERα-DNA binding may be a useful therapeutic and may represent a novel mechanism to bypass resistance to current antiestrogen therapies current antiestrogen therapies [55].

MOLECULAR MECHANISM OF ERE DNA RECOGNITION BY XR5944 [32]

We determined that XR5944 binds the ERE in the estrogen-responsive target gene TFF1 promoter (Fig. 1C) with high affinity (Fig. 6) [31]. The ideal bis-intercalating sequence 5’-T|GC|A (| represents the intercalation site) for XR5944 is not present in the TFF1-ERE, suggesting that the binding of XR5944 to native EREs may be different. Therefore, TFF1-ERE is a good candidate for structural characterization of XR5944 binding with natural ERE. The 15-mer TFF1-ERE DNA has a sequence of 5’-(AGGTCA CGGTGGCCA):(TGGCCACCGTGACCT)-3’ (Fig. 1C), which contains a 5’ consensus half-site, a 3’ non-consensus half-site, and a CGG tri-nucleotide spacer.

Fig. (6).

(A) Binding of XR5944 with the natural TFF1 ERE sequence by NMR. DNA was titrated with XR5944 at drug equivalences from 0 (bottom) to 2 (top).The imino proton peaks of the free EREs began to vanish while a new set of imino proton peaks corresponding to the drug-DNA complexes emerged upon addition of increasing concentrations of XR5944. An isolated imino proton peak of the free DNA is indicated by an asterisk (*) and dashed line (—). (B) The imino regions of 1D 1H NMR spectra of the free TFF1-ERE DNA duplex (top) and the 2:1 XR5944:TFF1 complex (bottom) with proton assignments.

XR5944 Forms a 2:1 Complex with TFF1-ERE DNA

The 1D 1H NMR titration data at pH 7 shows that, on the NMR time scale, XR5944 binds the TFF1-ERE DNA at a medium-to-slow exchange rate and with a binding stoichiometry of 2:1 (Fig. 6A). The dissociation constant KD of XR5944 was determined to be approximately 9.65 × 10−7 M by FID assay using ethidium bromide (EtBr). As the TFF1-ERE DNA is 15 nt long and is not palindromic, its NMR spectral overlapping is quite severe. We prepared site-specifically 15N-labeled DNA to achieve unambiguous assignment of imino H1/H3 and aromatic H8/H6 protons of guanine/thymine for each base pair in the free DNA and 2:1 XR5944-DNA complex (Fig. 6B). The imino protons of the two terminal A:T base pairs (T16 and T30) can be observed in the XR5944-DNA complex but not the free DNA (Fig. 6B), indicating the binding of XR5944 stabilizes the TFF1-ERE DNA duplex.

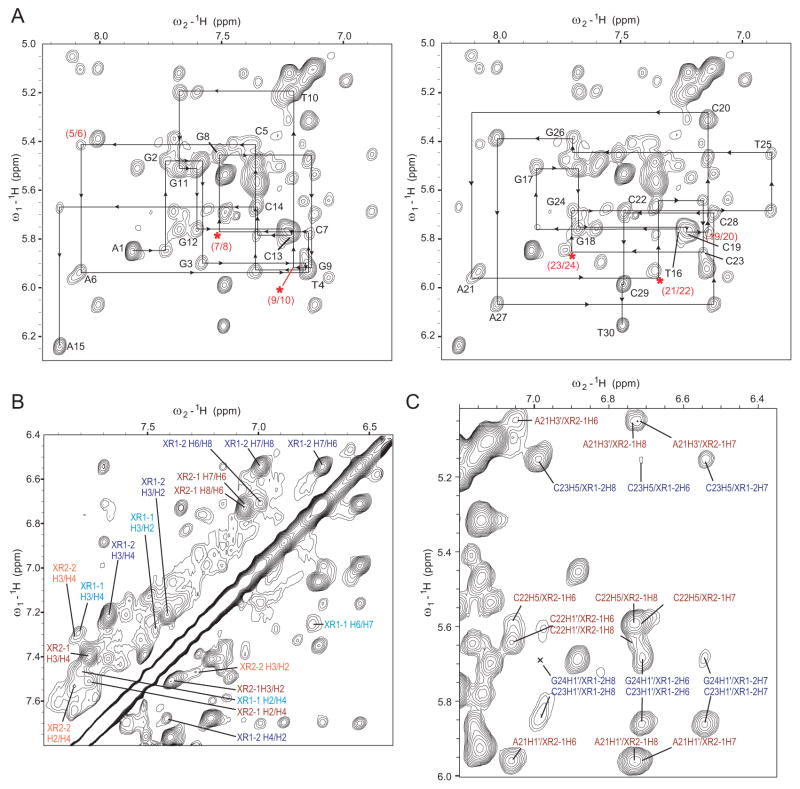

We completed proton assignments for both free TFF1 DNA duplex and the 2:1 XR5944-TFF1 complex using 2D- COSY, TOCSY and NOESY NMR data in water and D2O (Fig. 7). Notably, while the bound DNA protons are well defined and unambiguously assigned, only one intercalating phenazine ring of each binding XR5944, i.e., XR1-2 and XR2-1 (Fig. 1C), has unambiguous assignments for all proton resonances suggesting a well-defined conformation (Fig. 7). The second intercalating phenazine moieties of the two XR5944 molecules, i.e., XR1-1 and XR2-2, are less well defined as shown by much broader protons (Fig. 7B). Therefore, it appears that only one phenazine ring of each XR5944 binds strongly at the intercalating site, while the second phenazine binds weakly at the intercalating site and is more dynamic. Intermolecular NOE crosspeaks between XR5944 and TFF1-ERE DNA supported this. Only for the XR1-2 and XR2-1 strong binding sites could clearly defined intermolecular NOE crosspeaks be observed (Figs. 7C and 8). Un-like what was observed in the preferred binding site 5’-TGCA [23], the N10 of the phenazine ring of XR5944 (Fig. 1A) is not protonated in the 2:1 XR5944-TFF1 complex at pH7, likely due to weaker binding.

Fig. (7).

(A) The expanded aromatic-H1 region of the 2D-NOESY spectrum of the 2:1 XR5944-TFF1 complex. The sequential assignment pathways for the DNA sense strand (A1–A15) (left) and complement strand (T16-T30) (right) are shown. The intra-residue TFF1 DNA H8/H6-H1 NOEs are labeled with residue names. Missing (asterisks) or weak connectivities are labeled in red. (B) and (C) The expanded aromatic-aromatic (B) and aromatic - H1’ (C) regions of the 2D-NOESY spectrum of the 2:1 XR5944:TFF1 complex. The intra-XR5944 NOEs (B) and the intermolecular drug-DNA NOEs (C) assignments are shown. NOEs involving XR-1 and XR-2 phenazines are in blue and red respectively.

Fig. (8).

Schematic diagram of intermolecular NOEs of the two strong binding sites in the 2:1 XR5944-TFF1 complex between TFF1 DNA and the two intercalating drug phenazine rings: (A) XR1-2 of the first XR5944 molecule and (B) XR2-1 of the second XR5944 molecule. The solid, thick dashed, and thin dashed lines indicate strong, medium, and weak intensity NOEs respectively.

NMR Structure of the 2:1 XR5944-TFF1 ERE DNA Complex

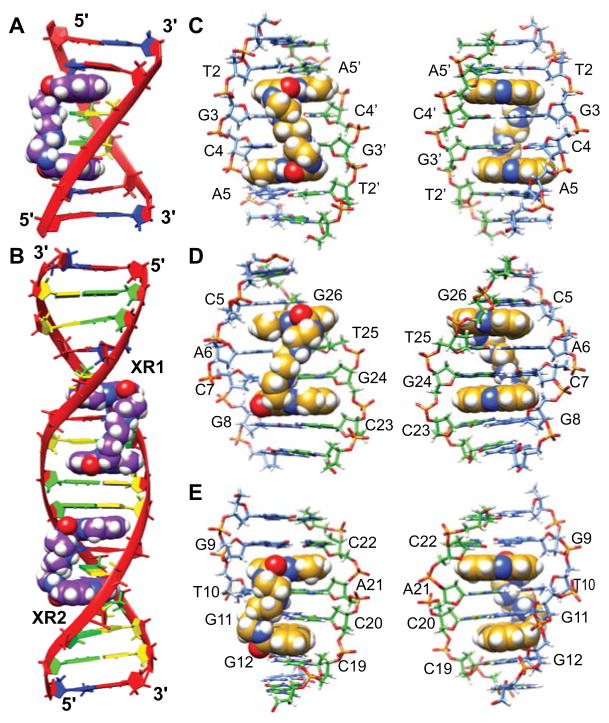

We determined NMR-refined structures of the 2:1 XR5944-TFF1 ERE complex (PDB ID 2mg8, Fig. 9). XR1, the first XR5944 molecule, bis-intercalates at the C5|pA6C7|pG8:C23|pG24T25|pG26 site (Fig. 9A–B), where C7|pG8:C23|pG24 is the strong intercalating site for XR1-2 phenazine ring. XR2, the second XR5944 molecule, bis-intercalates at the G9|pT10G11|pG12:C19|pC20A21|pC22 site (Fig. 9C–D), where G9|pT10:A21|pC22 is the strong intercalating site for the XR2-1 phenazine ring. Both XR5944 bis-intercalation sites involve the TFF1-ERE tri-nucleotide spacer. Within the CGG spacer in the TFF1-ERE sequence (Fig. 1C), the XR1-2 and XR2-1 phenazine chromophores are separated by only two base pairs G8:C23 and G9:C22 (Fig. 10B), such that the two strong binding sites of the two XR5944 drugs are adjacent to each other. Both XR1-2 and XR2-1 bind in a parallel intercalation mode at the strong binding sites, with the phenazine rings well stacked with the neighboring DNA base pairs (Fig. 9E–F). The intercalation conformations of the two weak binding sites, XR1-1 and XR2-2, exhibit higher conformational flexibility and are less well defined. Both XR5944 molecules have their carboxamide aminoalkyl linkers located within the TFF1-ERE DNA major groove (Fig. 9A,C).

Fig. (9).

Binding interactions within the two XR5944 complexes in the 2:1 XR5944-TFF1 complex structure. (A) and (B) XR1-DNA complex; (C) and (D) XR2-DNA complex. The major groove (left) and minor groove (right) views of the binding of the first XR5944 molecule XR1 (A) and the second XR5944 molecule XR2 (C), with the XR5944 molecules shown in CPK. The rises between base pairs at intercalation sites are also shown. DNA strands are colored by atom, with carbon atoms of one strand in green and another strand in light blue. (B) and (D) H-onding interactions (green dashed lines) between the DNA major groove and the carboxamide aminoalkyl linker of (B) XR1 and (D) XR2 in stereo view. Carbon atoms of XR5944 are colored yellow and hydrogen atoms are white. DNA strands are colored by atom, with carbon atoms in cyan. (E) and (F) Base-stacking interactions of XR1-2 (E) and XR2-1 (F) at the two strong intercalation sites. Carbon atoms of XR5944 are colored yellow and carbon atoms of DNA are colored by base pair. Nitrogen atoms are blue, oxygen atoms are red, and phosphorus atoms are orange. DNA sequences are labeled.

Fig. (10).

(A)–(B) Representative models of 1:1 XR5944 - d(ATGCAT)2 complex (A) and 2:1 XR5944-TFF1 complex (B). The XR5944 molecules are shown in CPK model. Adenine, thymine, guanine and cytosine are red, blue, green and yellow, respectively. (C)–(E) XR5944 complexes in the 1:1 XR5944 - d(ATGCAT)2 complex (C), the first XR1 (D) and second XR2 (E) drug complex in the 2:1 XR5944-TFF1 complex, viewed from the major groove (left) and the minor groove (right). The XR5944 molecules are shown in CPK model. DNA sequences are labeled.

At the strong intercalation sites, the rise between the two intercalated base pairs is ~6.01 Å at the XR1-2 intercalation site (C7|pG8):(C23|pG24) (Fig. 9A), and is ~6.34 Å at the XR2-1 intercalation site (G9|pT10):(A21|pC22) (Fig. 9C). The rise at the two weak intercalation sites, (C5|pA6):(T25|pG26) and (G11|pG12):(C19|pC20), is 5.95 Å and 5.86 Å, respectively (Fig. 9A, C). The rises at all four intercalation sites are greater than those seen in perpendicular intercalation sites, such as anthracycline drugs [34, 35], but smaller than those of the minor-groove binding bis-intercalators, such as echinomycin (7.25 Å and 6.81 Å) [56] and triostin A (7.25 Å and 6.99 Å) [57]. At both XR5944-DNA complexes, the DNA double-helix is unwound, with the overall unwinding being 32° for the first drug (XR1) 3-step binding site of C5A6C7G8 (Fig. 9B), and 28° for the second drug (XR2) binding site of G9T10G11G12 (Fig. 9D), as compared to standard B-DNA which has an average helical twist of 36° per step. This unwinding is significantly less than that observed in the XR5944 complex with DNA hexamer d(ATGCAT)2 [23], likely due to the restraints of the longer ERE DNA (15-mer). Extending to the ±1 steps adjacent to the intercalation site, the DNA unwinding reduces to about 4–5°. The unwinding is larger at the central G8pG9:C22pC23 step between the two XR5944 complexes ( ~7°), likely due to the combined influence of the two adjacent intercalation sites.

The two positively charged linker γ-amino groups of XR5944 (Fig. 1A) interact favorably within the electronegative major groove of DNA and can form H-bonds with O4 of thymine and O6 of guanine in the major groove. In the first XR5944(XR1)-DNA complex, potential H-bonds appear to form between the amide and γ-amino hydrogens of XR1-1 and T25O4, and between XR1-2 and G24O6 (Fig. 9B). In the second XR5944(XR2)-DNA complex, potential H-bonds appear to form between XR2-1 and T10O4, and XR2-2 and G11O6 (Fig. 9D). Intriguingly, in the two XR5944-DNA complexes, the carboxamide aminoalkyl linkers of the two drug molecules adopt different conformations. The XR1 drug has the appearance of a “Z” when viewed from the major groove with its linker running diagonally across the major groove with a right-handed twist (Fig. 9A), whereas the XR2 linker runs across the major groove more vertically (Fig. 9C).

Unexpected Bis-Intercalation Sites of XR5944 within the TFF1-ERE DNA Duplex

We have previously shown that the ideal DNA binding sequence of XR5944 is the 5’-T|GC|A with two symmetric 5’-(TpG):(CpA) bis-intercalating sites [23] (Fig. 4). The preferred bis-intercalating DNA sequence 5’-TGCA is not present in the TFF1-ERE sequence, which contains a 5’-CpA and a 5’-TpG site at each of the half-sites 5’-(AGGTCACGGTGGCCA). One important notion is, while equivalent as a single intercalating site, 5’-CpA and 5’-TpG sites are non-equivalent in a bis-intercalation binding, which becomes directional due to the linker connection. For example, 5’-TGCA and 5’-CATG are two different arrangements of 5’-TpG and 5’-CpA steps; however, the two central base-pairs wrapped by the two intercalating phenazines are G:Cs in the 5’-TGCA sequence, but become A:Ts in 5’-CATG. Indeed, compared to binding at the ideal bis-intercalation sequence 5’-TGCA, our results showed a different binding characteristics of XR5944 to the TFF1-ERE DNA sequence. Specifically, XR5944 binds strongly at one intercalation site but weakly at the second intercalation site in each drug-DNA complex within the TFF1-ERE DNA (Fig. 1C). In the XR1-DNA complex, the strong intercalation site is 5’-C7pG8 for XR1-2, whereas the weak intercalation site is 5’-C5pA6 for XR1-1.

The second bis-intercalation site of XR5944 (XR2), 5’-G9T10G11G12, is unexpected (Fig. 1C). The strong binding site in this XR2-DNA complex is 5’-G9pT10 for XR2-1 phenazine. Both G9pT10 and G11pG12 are purine-N steps, which are known to disfavor the intercalation binding due to less flexibility in accommodating the structure distortion [36, 37, 58, 59]. 5’-T10G11G12C13, which is one base downstream, contains a preferred intercalation site of 5’-TpG and was expected to be the second XR binding site (Fig. 1C). It is likely that the binding of the first drug may influence the binding site of the second drug. 5’-C5pA6C7pG8 is likely to be the first binding site of XR5944 due to its favorable intercalation interactions. The negative supercoiling (unwinding) of DNA induced by the first binding site favors the binding of the second drug; however, this favorable unwinding can only propagate to the adjacent steps, but disappear at a more distant site, hence disfavoring the binding of the second XR5944 at the farther 5’-T10G11G12C13 site. Indeed, in the 1:1 XR5944 complex with shorter DNA hexamer 5’-ATGCAT, the unwinding at the terminal ApT step, which is adjacent to the TpG intercalation site, is as large as 13° [23].

As the left half-site of the TFF1-ERE sequence is the consensus ERE half-site (Fig. 5A–B) and is the first drug binding site, XR5944 likely binds at the same sites in the consensus ERE sequence with a CGG spacer. Indeed, our NMR titration data showed a very similar binding pattern of XR59444 to the consensus ERE sequence with a CGG spacer (Fig. 5C).

Diverse Intercalation Modes of the Phenazine Moieties of XR5944

While all are involved in parallel base-stacking intercalation, the binding positions of the XR5944 phenazine rings appear to be diverse of the intercalation sites, including the two strong binding sites within the TFF1-ERE DNA (Fig. 9E–F), and the preferred 5’-TGCA sequence [23] (Fig. 4D). In the case of the first strong binding site (C7pG8):(C23pG24), the XR1-2 phenazine ring stacks more extensively inside the C23pG24 step than the C7pG8 step and is clearly located in more proximity to the C23pG24 sugar backbone (Fig. 9E). At the second strong binding site, (G9pT10):(A21pC22), a more symmetric intercalation was observed for XR2-1 (Fig. 9F). At the two weak binding sites, although not as well defined, XR1-1 appears to intercalate more extensively within the (C5pA6):(T25pG26) step as compared to the intercalation of XR2-2 at the (G11pG12):(C19pC20) site (Fig. 9A–D).

More remarkably, the XR phenazine rings adopt different intercalation orientations in the three drug complexes, which result in different linker conformations in the DNA major groove (Fig. 10). In the XR5944 complex with the ideal 5’-TGCA binding site [23] (Fig. 10A), the ring A of phenazine (where the linker connects) is close to the descending DNA strand when viewing into the major groove, therefore, the linker connecting the two phenazines adopts a conformation with left-handed twist (Fig. 10C). In the XR1 complex with the TFF1-ERE DNA sequence, the ring A is closer to the opposite DNA strand (ascending), resulting in the opposite intercalation orientations of the two phenazines and thus a different linker conformation adopting right-handed twist (Fig. 10D). In the XR2 complex with the TFF1-ERE (Fig. 10B), although the tight binding phenazine XR2-1 has a similar orientation to that of XR at the ideal binding site 5’-TGCA, the poor XR2-2 intercalation at the weak binding site results in a more vertical linker conformation (Fig. 10E).

XR5944 Interactions with the DNA Major Groove

Two H-bond acceptors, guanine O6 and thymine O4, are present in the DNA major groove and are available to the XR5944 linker γ-amino groups for hydrogen bonding. Guanine O6 is better accessible for major groove H-bonding. In the ideal binding site 5’-TGCA, the H-bond acceptors guanine O6 of the two central G:C base pairs, wrapped by the two intercalating XR phenazine rings, are symmetrically located on the two different DNA strands (Fig. 4C). In contrast, in both XR1 and XR2 complexes within the TFF1-ERE DNA, the major groove H-bond acceptors are located on the same DNA strand: G24O6 and T25O4 of the XR1 complex (Fig. 9B), and T10O4 and G11O6 of the XR2 complex (Fig. 9D), which are less accessible for the H-bonding interactions. The location of the major groove H-bond acceptors at the non-ideal XR1 and XR2 binding sites may determine the divers positioning and different orientations of the phenazine moieties at the intercalation sites. For example, in the XR1 binding site (C5|pA6C7|pG8):(C23|pG24T25|pG26) (Fig. 9A–B), to facilitate H-bond interactions with G24O6 and T25O4, both XR1-1 and XR1-2 phenazines are positioned closer to the C23|pG24T25|pG26 strand (Fig. 9E). In the XR2 complex (Fig. 9C–D), the two H-bond acceptors T10O4 and G11O6 are located on the opposite strand as compared to the XR1 complex, which results in a different phenazine orientation of XR2 (Fig. 9F) to facilitate better access of its linker to the major groove H-bond acceptors (Fig. 9D).

Notably, while having two adjacent guanine O6 atoms on the complementary strands provides the most favorable hydrogen bonding interactions in the DNA major groove (Fig. 4C) [23], having two adjacent guanine O6 atoms on the same DNA strand is much less accessible due to the helical twist of DNA. Thus, a bis-intercalator sandwiching a central GpG sequence would be disfavored. In contrast, a guanine O6 and thymine O4 on the same DNA strand may be more accessible for the H-bond interactions in the major groove, as seen in the XR1 and XR2 complexes (Fig. 9). This could be another factor that hinders the binding of XR2 to the 5’-T10G11G12C13 site, which has a central GpG sequence (Fig. 1C). It thus appears that both the phenazine intercalation interactions and the linker major groove interactions determine the XR5944 binding sites at a non-ideal binding sequence. The phenazine moiety may shift from an ideal intercalation mode to facilitate better hydrogen bonding interactions of the linker in the major groove. This may be the reason for different phenazine orientations and asymmetric positioning, as well as weak and strong intercalation binding, of XR5944 at non-ideal binding sites.

Design of Improved ERE DNA Targeted Bis-Intercalator Compounds

Understanding the XR5944 binding mode with a natural ERE promoter sequence may provide an important basis towards designing ERE-targeted XR5944 derivatives. Our studies suggest that XR5944-derived DNA bis-intercalators with improved specificity to the ERE DNA may be developed by optimizing the aminoalkyl linker and the intercalating moieties at the weak binding sites. The major groove hydrogen bonding interactions appear to be important to the formation of a stable drug complex, which could be optimized for the ERE sequence by linker modifications. Flexible linkers are known to improve small molecule binding affinity at the cost of sequence selectivity [60], therefore, improved sequence specificity may be gained by incorporation of a rigid linker, as utilized by several earlier DNA intercalators [61–63]. Additionally, the aminoalkyl chain length may be modified to optimize the major groove hydrogen bonding interactions with the ERE sequence. Furthermore, weaker intercalation interactions at the two weak binding sites may be improved by substitution of the phenazine with other intercalating moieties for a stronger binding.

CONCLUSION

Our studies show that XR5944, a DNA bis-intercalator with exceptional anticancer activity, has a novel DNA binding mode: DNA bis-intercalation with major-groove binding. We found the ideal DNA sequence for XR5944 bis-intercalation is 5’-T|GC|A, which contains two symmetric 5’-(TpG):(CpA) binding sites [23]. Our NMR solution structure of the 1:1 XR5944: d(ATGCAT)2 complex provides insights into site-specific DNA recognition of XR5944. The TpG binding site is found in each of the consensus ERE half-sites, and we showed that XR5944 can inhibit ERα-mediated transcriptional responses by blocking ERα-ERE DNA binding [31]. Targeting ERE DNA is a novel mechanism of action and may be used to overcome the common routes of drug resistance to current antiestrogen treatments, which all target the estrogen-receptor complex. We showed that the tri-nucleotide spacer clearly affects XR5944-ERE binding affinity, which correlates with XR5944 efficacy in transcriptional inhibition of ERα-mediated activity. [31]. We found that XR5944 binds the natural TFF1 ERE DNA with sufficient affinity for NMR structure determination. Our NMR structure of the 2:1 complex of XR5944 with the natural TFF1-ERE promoter sequence allows us to understand the specific molecular recognition between ERE sequence and XR5944 [32]. The intercalation sites in a native promoter sequence differ from the ideal binding site and are context- and sequence- dependent. Both drug complexes involve the spacer sequence of TFF1-ERE. Our structures showed that XR5944 binds strongly at one intercalation site and weakly at the second intercalation site in both drug-DNA complexes with TFF1-ERE sequence. The drug binding at one bis-intercalation site can affect the binding site of the second drug. Our results indicate that the DNA binding of a bis-intercalator is directional and different from the simple addition of two single intercalation sites. Our studies suggest that improved DNA bis-intercalators targeting ERE may be designed by optimization of intercalation moieties at the weak binding sites and aminoalkyl linkers. These insights may be important for designing of ERE-specific XR5944 derivatives, as well as the DNA bis-intercalators in general.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for Dr. William Denny for the insightful discussion. We thank Xenova Ltd. (Slough, UK) for providing us with the XR5944 compound. We thank Dr. Megan Carver for proofreading the manuscript.

FUNDING

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health [CA129424, 1S10 RR16659, 1K01CA83886].

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Cheung-Ong K, Giaever G, Nislow C. DNA-damaging agents in cancer chemotherapy: serendipity and chemical biology. Chem Biol. 2013;20(5):648–659. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang DZ, Wang AHJ. Structural studies of interactions between anticancer platinum drugs and DNA. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1996;66(1):81–111. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(96)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang AHJ. Intercalative drug binding to DNA. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1992;2(3):361–368. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denny WA, Baguley BC. Dual topoisomerase I/II inhibitors in cancer therapy. Curr Top Med Chem. 2003;3(3):339–353. doi: 10.2174/1568026033452555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan GS, Shah A, Ziaur R, Barker D. Chemistry of DNA minor groove binding agents. J Photochem Photobiol B, Biology. 2012;115(0):105–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dervan PB. Molecular recognition of DNA by small molecules. Bioorg Med Chem. 2001;9(9):2215–2235. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao C, Ren J, Gregoliński J, Lisowski J, Qu X. Contrasting enantioselective DNA preference: chiral helical macrocyclic lanthanide complex binding to DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(16):8186–8196. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamilton PL, Arya DP. Natural product DNA major groove binders. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29(2):134–143. doi: 10.1039/c1np00054c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knapp S, Sundstrom M. Recently targeted kinases and their inhibitors-the path to clinical trials. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2014;17C(0):58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barouch-Bentov R, Sauer K. Mechanisms of drug resistance in kinases. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2011;20(2):153–208. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2011.546344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byers SA, Schafer B, Sappal DS, Brown J, Price DH. The antiproliferative agent MLN944 preferentially inhibits transcription. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4(8):1260–1267. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gamage SA, Spicer JA, Finlay GJ, Stewart AJ, Charlton P, Baguley BC, Denny WA. Dicationic bis(9-methylphenazine-1-carboxamides): Relationships between biological activity and linker chain structure for a series of potent topoisomerase targeted anticancer drugs. J Med Chem. 2001;44(9):1407–1415. doi: 10.1021/jm0003283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finlay GJ, Riou JF, Baguley BC. From amsacrine to DACA (N-[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl]acridine-4-carboxamide): Selectivity for topoisomerases I and II among acridine derivatives. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A(4):708–714. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00604-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mistry P, Stewart AJ, Dangerfield W, Baker M, Liddle C, Bootle D, Kofler B, Laurie D, Denny WA, Baguley B, Charlton PA. In vitro and in vivo characterization of XR11576, a novel, orally active, dual inhibitor of topoisomerase I and II. Anticancer Drugs. 2002;13(1):15–28. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200201000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vicker N, Burgess L, Chuckowree IS, Dodd R, Folkes AJ, Hardick DJ, Hancox TC, Miller W, Milton J, Sohal S, Wang SM, Wren SP, Charlton PA, Dangerfield W, Liddle C, Mistry P, Stewart AJ, Denny WA. Novel angular benzo-phenazines: Dual topoisomerase I and topoisomerase II inhibitors as potential anticancer agents. J Med Chem. 2002;45(3):721–739. doi: 10.1021/jm010329a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stewart AJ, Mistry P, Dangerfield W, Bootle D, Baker M, Kofler B, Okiji S, Baguley BC, Denny WA, Charlton PA. Antitumor activity of XR5944, a novel and potent topoisomerase poison. Anticancer Drugs. 2001;12(4):359–367. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200104000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sappal DS, McClendon AK, Fleming JA, Thoroddsen V, Connolly K, Reimer C, Blackman RK, Bulawa CE, Osheroff N, Charlton P, Rudolph-Owen LA. Biological characterization of MLN944: a potent DNA binding agent. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3(1):47–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Nicolantonio F, Knight LA, Whitehouse PA, Mercer SJ, Sharma S, Charlton PA, Norris D, Cree IA. The ex vivo characterization of XR5944 (MLN944) against a panel of human clinical tumor samples. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3(12):1631–1637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris SM, Mistry P, Freathy C, Brown JL, Charlton PA. Antitumour activity of XR5944 in vitro and in vivo in combination with 5-fluorouracil and irinotecan in colon cancer cell lines. Br J Cancer. 2005;92(4):722–728. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris SM, Scott JA, Brown JL, Charlton PA, Mistry P. Preclinical anti-tumor activity of XR5944 in combination with carboplatin or doxorubicin in non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Anticancer Drugs. 2005;16(9):945–951. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000176499.17939.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson C. Visual surface and visual symbol: the microscope and the occult in early modern science. J Hist Ideas. 1988;49(1):85–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Todd AK, Adams A, Thorpe JH, Denny WA, Wakelin LPG, Cardin CJ. Major groove binding and ‘DNA-induced’ fit in the intercalation of a derivative of the mixed topoisomerase I/II poison N-(2-(dimethylamino)ethyl)acridine-4-carboxamide (DACA) into DNA: X-ray structure complexed to d(CG(5- BrU)ACG)(2) at 1.3-angstrom resolution. J Med Chem. 1999;42(4):536–540. doi: 10.1021/jm980479u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dai J, Punchihewa C, Mistry P, Ooi AT, Yang DZ. Novel DNA bis-intercalation by MLN944, a potent clinical bisphenazine anticancer drug. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(44):46096–46103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404053200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones S, van Heyningen P, Berman HM, Thornton JM. Protein-DNA interactions: A structural analysis. J Mol Biol. 1999;287(5):877–896. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klinge CM. Estrogen receptor interaction with estrogen response elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(14):2905–2919. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.14.2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beato M, Chalepakis G, Schauer M, Slater EP. DNA regulatory elements for steroid hormones. J Steroid Biochem. 1989;32(5):737–747. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(89)90521-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lannigan DA, Notides AC. Estrogen regulation of transcription. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1990;322:187–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwabe JWR, Chapman L, Finch JT, Rhodes D. The crystal structure of the estrogen receptor DNA binding domain bound to DNA - How receptors discriminate between their response elements. Cell. 1993;75(3):567–578. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90390-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Punchihewa C, De Alba A, Sidell N, Yang D. XR5944: A potent inhibitor of estrogen receptors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(1):213–219. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Catherino WH, Wolf DM, Jordan VC. A naturally occurring estrogen receptor mutation results in increased estrogenicity of a tamoxifen analog. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9(8):1053–1063. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.8.7476979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sidell N, Mathad RI, Shu FJ, Zhang ZJ, Kallen CB, Yang DZ. Intercalation of XR5944 with the estrogen response element is modulated by the tri-nucleotide spacer sequence between half-sites. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;124(3–5):121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin C, Mathad RI, Zhang Z, Sidell N, Yang D. Solution structure of a 2:1 complex of anticancer drug XR5944 with TFF1 estrogen response element: insights into DNA recognition by a bis-intercalator. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(9):6012–6024. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng G, Lu X-J, Olson WK. Web 3DNA—a web server for the analysis, reconstruction, and visualization of three-dimensional nucleic-acid structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(suppl 2):W240–W246. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang DZ, Wang AHJ. Structure by NMR of antitumor drugs aclacinomycin-A and aclacinomycin-B complexed to d(CGTACG) Biochemistry. 1994;33(21):6595–6604. doi: 10.1021/bi00187a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang AHJ, Ughetto G, Quigley GJ, Rich A. Interactions between an anthracycline antibiotic and DNA - Molecular structure of daunomycin complexed to d(CpGpTpApCpG) at 1.2A resolution. Biochemistry. 1987;26(4):1152–1163. doi: 10.1021/bi00378a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gorin AA, Zhurkin VB, Olson WK. B-DNA twisting correlates with base-pair morphology. J Mol Biol. 1995;247(1):34–48. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dornberger U, Flemming J, Fritzsche H. Structure determination and analysis of helix parameters in the DNA decamer d(CATGGCCATG)2 comparison of results from NMR and crystallography. J Mol Biol. 1998;284(5):1453–1463. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palmer BD, Rewcastle GW, Atwell GJ, Baguley BC, Denny WA. Potential antitumor agents .54. Chromophore requirements for in vivo antitumor activity among the general class of linear tricyclic carboxamides. J Med Chem. 1988;31(4):707–712. doi: 10.1021/jm00399a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao Q, Williams LD, Egli M, Rabinovich D, Chen SL, Quigley GJ, Rich A. Drug-induced DNA repair: X-ray structure of a DNA-ditercalinium complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(6):2422–2426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamitori S, Takusagawa F. Crystal-Structure of the 2/1 Complex between d(GAAGCTTC) and the anticancer drug actinomycin-D. J Mol Biol. 1992;225(2):445–456. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90931-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baker EN, Hubbard RE. Hydrogen bonding in globular proteins. Prog Biophy Mol Biol. 1984;44(2):97–179. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(84)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yager JD, Davidson NE. Estrogen carcinogenesis in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(3):270–282. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jensen EV, Jacobson HI. Basic guides to the mechanism of estrogen action. Recent Prog Hormone Res. 1962;18:387–414. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bjornstrom L, Sjoberg M. Mechanisms of estrogen receptor signaling: convergence of genomic and nongenomic actions on target genes. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(4):833–842. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pearce ST, Jordan VC. The biological role of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in cancer. Critical Rev Oncol Hematol. 2004;50(1):3–22. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cai W, Hu L, Foulkes JG. Transcription-modulating drugs: mechanism and selectivity. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1996;7(6):608–615. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(96)80071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campos SM. Aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer in post-menopausal women. Oncologist. 2004;9(2):126–136. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-2-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weinberg OK, Marquez-Garban DC, Pietras RJ. New approaches to reverse resistance to hormonal therapy in human breast cancer. Drug Resist Updat : Reviews and Commentaries in Antimicrobial and Anticancer Chemotherapy. 2005;8(4):219–233. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kurebayashi J. Resistance to endocrine therapy in breast cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2005;56(Suppl 1):39–46. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0099-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schiff R, Chamness GC, Brown PH. Advances in breast cancer treatment and prevention: preclinical studies on aromatase inhibitors and new selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) Breast Cancer Res. 2003;5(5):228–231. doi: 10.1186/bcr626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mason CE, Shu FJ, Wang C, Session RM, Kallen RG, Sidell N, Yu T, Liu MH, Cheung E, Kallen CB. Location analysis for the estrogen receptor-alpha reveals binding to diverse ERE sequences and widespread binding within repetitive DNA elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(7):2355–2368. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shu FJ, Sidell N, Yang DZ, Kallen CB. The tri-nucleotide spacer sequence between estrogen response element half-sites is conserved and modulates ERalpha-mediated transcriptional responses. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;120(4–5):172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Auchus RJ, Fuqua SA. Clinical syndromes of hormone receptor mutations: hormone resistance and independence. Semin Cell Biol. 1994;5(2):127–136. doi: 10.1006/scel.1994.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Michalides R, Griekspoor A, Balkenende A, Verwoerd D, Janssen L, Jalink K, Floore A, Velds A, van’t Veer L, Neefjes J. Tamoxifen resistance by a conformational arrest of the estrogen receptor alpha after PKA activation in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;5(6):597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jordan VC. How is tamoxifen’s action subverted? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(2):92–94. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.2.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cuesta-Seijo JA, Sheldrick GM. Structures of complexes between echinomycin and duplex DNA. Acta Crystallographica. Section D, Biological Crystallography. 2005;61(Pt 4):442–448. doi: 10.1107/S090744490500137X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Addess KJ, Sinsheimer JS, Feigon J. Solution structure of a complex between [N-MeCys3,N-MeCys7]TANDEM and [d(GATATC)]2. Biochemistry. 1993;32(10):2498–2508. doi: 10.1021/bi00061a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dickerson RE. DNA bending: the prevalence of kinkiness and the virtues of normality. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26(8):1906–1926. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.8.1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suzuki M, Yagi N. Stereochemical basis of DNA bending by transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23(12):2083–2091. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.12.2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Denny WA, Atwell GJ, Baguley BC, Wakelin LP. Potential antitumor agents. 44. Synthesis and antitumor activity of new classes of diacridines: importance of linker chain rigidity for DNA binding kinetics and biological activity. J Med Chem. 1985;28(11):1568–1574. doi: 10.1021/jm00149a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van Vliet LD, Ellis T, Foley PJ, Liu L, Pfeffer FM, Russell RA, Warrener RN, Hollfelder F, Waring MJ. Molecular recognition of DNA by rigid [N]-polynorbornane-derived bifunctional intercalators: synthesis and evaluation of their binding properties. J Med Chem. 2007;50(10):2326–2340. doi: 10.1021/jm0613020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nazif MA, Rubbiani R, Alborzinia H, Kitanovic I, Wolfl S, Ott I, Sheldrick WS. Cytotoxicity and cellular impact of dinuclear organoiridium DNA intercalators and nucleases with long rigid bridging ligands. Dalton Trans. 2012;41(18):5587–5598. doi: 10.1039/c2dt00011c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Priebe W, Perez-Soler R. Design and tumor targeting of anthra-cyclines able to overcome multidrug resistance: a double-advantage approach. Pharmacol Ther. 1993;60(2):215–234. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(93)90007-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]