Abstract

Deficiencies in omega-3 (n-3) long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFAs) and increases in the ratio of omega-6 (n-6) to n-3 LC-PUFAs in brain tissues and blood components have been associated with psychiatric and developmental disorders. Most studies have focused on n-3 LC-PUFA accumulation in the brain from birth until 2 years of age, well before the symptomatic onset of such disorders. The current study addresses changes that occur in childhood and adolescence. Postmortem brain (cortical gray matter, inferior temporal lobe; n=50) and liver (n=60) from vervet monkeys fed a uniform diet from birth through young adulthood were collected from archived tissues. Lipids were extracted and fatty acid levels determined. There was a marked reduction in the ratio of n-6 LC-PUFAs, arachidonic acid (ARA) and adrenic acid (ADR), relative to the n-3 LC-PUFA, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), in temporal cortex lipids from birth to puberty and then a more gradual decrease though adulthood. This decrease in ratio resulted from a 3-fold accumulation of DHA levels while concentrations of ARA remained constant. Early childhood through adolescence appears to be a critical period for DHA accretion in the cortex of vervet monkeys and may represent a vulnerable stage where lack of dietary n-3 LC-PUFAs impacts development in humans.

Keywords: Docosahexaenoic acid, arachidonic acid, psychiatric and developmental disorders, omega-3 deficiency, brain

1. INTRODUCTION

The brain is highly enriched in lipids and particularly long chain (>20 carbons) polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFAs). Additionally, it is well established that adequate dietary intake of LC-PUFA is important for proper neural development during prenatal and postnatal periods up to 2 years of age [1–5]. This is especially the case for docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, C22:6 n-3) and arachidonic acid (ARA, C20:4 n-6), the most abundant LC-PUFAs in the brain and retina. The last trimester and particularly the last 5 weeks of pregnancy appear to be a critical period of time for DHA and ARA accretion in the fetal brain [6]. Additionally, DHA and ARA have distinct roles in brain function and a balance of DHA and ARA, and thus specific DHA/ARA ratios, appear to be required for optimal mental health [7].

Numerous studies indicate that DHA deficiency and altered ratios of n-6 to n-3 LC-PUFAs are associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity (ADHD), schizophrenia, autism spectrum (ASD) and major depressive disorders (MDD) in children, adolescents and young adults [8–24]. Given the symptomatic onset of many of these diseases typically occurs during periods of rapid cortical circuit maturation from early childhood to adulthood, there is a need to better understand alterations in LC-PUFAs within critical regions of the brain during this period of time [25]. Initial studies by Martinez and Mougan demonstrated that DHA increased while ARA remained constant in forebrains of humans up until 7 years of age [26]. Carver and colleagues later showed that there was a bilinear increase in cortical DHA levels in humans, with the latter phase continuing until 18 years of age [27]. In contrast to DHA, ARA and its elongation product, adrenic acid (ADR, C22:4 n-6) decreased during this second phase. DHA in cortex phospholipids (particularly ethanolamine-containing phospholipids) also increases approximately 2 fold from birth to 22 months of age in rhesus monkeys [4]. Together, these studies suggest that there may be an important period of time after early childhood where dietary ingestion and biosynthesis of DHA but not ARA may be particularly important. The objective of the current study was to expand these studies in a non-human primate model where critical environmental variables such as diet could be strictly controlled.

LC-PUFAs are obtained directly from the diet or synthesized in tissues from essential dietary 18 carbon PUFA precursors, such as α-linolenic acid (ALA, C18:3 n-3) and linoleic acid (LA, C18:2 n-6). For example, ARA is synthesized from LA using alternating desaturation and elongation enzymatic steps [28, 29]. DHA is initially synthesized from dietary ALA utilizing the same desaturation and elongation steps to form C24:6 n-3. Historically, it has been proposed that C24:6 n-3 is then converted to DHA by a peroxisomal β-oxidation step. However, a recent study suggests mammals can also utilize an alternative pathway for DHA biosynthesis where a double bond is introduced at the Δ4 position of docosapentaenoic acid (DPA, C22:5 n-3) to form DHA [29].

Much of the capacity to synthesize LC-PUFAs is thought to reside in the liver. Once formed, LC-PUFAs are released into circulation as complex lipids (phospholipids, lyso-phospholipids, triglycerides, and cholesterol esters) or free fatty acids. These LC-PUFAs can then be specifically transported into tissues such as the brain [30–36]. Additionally, cells within the brain, including astrocytes and some neurons, have been shown to synthesize low levels of ARA and DHA from LA and ALA, respectively, in vitro [37].

Significant challenges to a better understanding of LC-PUFA metabolism and accretion after prenatal and early postnatal periods include: 1) the lack of access to human brain tissue from different age groups; 2) genetic differences in the capacity of different human populations to synthesize tissue LC-PUFAs; and 3) variance in human diets that impact tissue levels of LC-PUFAs. Studies in rodent models have attempted to bridge these gaps, but differences in LC-PUFA biosynthesis and metabolism [38] and brain structure between rodent and humans make translation of the findings difficult. The current study was designed to address the question of whether there are temporal changes in LC-PUFA levels in the brain over the early lifespan by focusing on the fatty acid (FA) composition of the temporal lobe cortex verses the liver in the vervet monkey. We measured LC-PUFA from archived liver and brain tissues collected from animals raised on uniform diets from birth to early adulthood. We show that levels of DHA and ratios n-3 and n-6 LC-PUFAs change dramatically within cortical brain tissue of vervet monkeys during the first three years of development.

2. METHODS

2.1 Animals and Tissues

The Vervet Research Colony at Wake Forest Primate Center is a multigenerational pedigreed colony of vervets/African green monkeys (Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus) [39]. Animals included in this study were of known-age, US-born, mother-reared and housed in identical indoor-outdoor matrilineal social groups. Archived brain and liver tissue samples were received for 53 and 64 vervets, respectively. Brain tissues were retrieved from the cortex of the inferior temporal lobe. The characteristics of animals used in this study are shown in Table 1. Tissue samples were organized into nine age groups ranging from less than one day to 8.8 years (Table 1). Vervet females and males reach puberty at ~2.5 and ~3 years of age, respectively [39].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the animals and tissues.

| Age | # Males | # Females | Mean Age (Days) | Mean Body Weight (kg) | Mean Brain Weight (g) | Mean Liver Weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth | 3 | 2 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 43.5 | 10.6 |

| ~1 week | 3 | 2 | 7.6 | 0.3 | 43.2 | 10.1 |

| 1–3 months | 8 | 7 | 60.3 | 0.6 | 60.2 | 18.8 |

| 6–12 months | 5 | 6 | 254.0 | 1.4 | 69.6 | 37.3 |

| 1–2 years | 5 | 8 | 654.0 | 2.5 | 74.5 | 56.6 |

| 2–3 years | 4 | 3 | 982.3 | 3.7 | 77.1 | 74.7 |

| 3–7 years | 1 | 2 | 1441.7 | 4.4 | 73.6 | 105.6 |

| 7 + years | 3 | 2 | 3018.8 | 2.5 | 71.0 | 58.6 |

Tissues were collected during experimental necropsies that were part of a separate study. Animals were anesthetized with ketamine (10–20 mg/kg, i.m.) and then administered sodium pentobarbital (60–100 mg/kg i.v.) to a deep plane of anesthesia. The chest was opened, a 14G needle was inserted into the left ventricle, a 1 cm incision was made in the inferior vena cava and the vasculature was flushed with cold saline until outflow was clear (~5–10 minutes). The brain was removed from the skull, weighed and hemisected. A section of the temporal lobe from the left hemisphere was frozen in liquid nitrogen and transferred to a −80°C freezer for long-term storage. An aliquot of liver was also collected, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

2.2 Diets

Animals younger than three months nursed from mothers that consumed the Chow LabDiet 5038 (13.1% calories from fat; LabDiet, St. Louis, MO). It is possible that these young animals consumed chow in addition to mother’s milk, although this was not actively observed by caretakers. Animals above the age of three months received Chow LabDiet 5038 and water ad libitum until the time of necropsy. Table 2 shows the composition of the LabDiet (manufacturer data) and our analysis of the FA composition of the chow diet measured by gas chromatography/flame ionization detection (GC/FID) of fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) for tissue lipids.

Table 2. Composition of the chow diet.

This Labdiet 5038 (LabDiet, St. Louis, MO) was consumed by all animals after cessation of nursing. Data in the diet composition section of this table were obtained from the nutritional facts published by LabDiet (http://www.labdiet.com/Products/StandardDiets/Primates/index.htm). Fatty acid composition was analyzed by GC/FID as described in the methods section.

| Diet Composition | |

|---|---|

| Protein (%) | 18.2 |

| Carbohydrates (%) | 68.7 |

| Cholesterol (ppm) | 75.0 |

| Fat (%) | 13.1 |

|

| |

| Fatty Acid | % of Total Fatty Acids |

|

| |

| C14:0 [myristolate] | 1.0 |

| C16:0 [palmitic] | 19.8 |

| C16:1 [palmitoleic] | 1.4 |

| C18:0 [stearic] | 7.9 |

| C18:1 n-9 [oleic] | 28.5 |

| C18:1 n-11 | 2.3 |

| C18:2 n-6 [LA] | 35.2 |

| C18:3 n-3 [ALA] | 2.3 |

| C20:1 n-9 | 0.6 |

| C20:2 n-6 | 0.3 |

| C20:4 n-6 [ARA] | 0.1 |

| C20:5 n-3 [EPA] | 0.3 |

| C22:6 n-3 [DHA] | 0.2 |

|

| |

| SFA + MUFA/PUFA | 1.6 |

|

| |

| n-6/n-3 PUFA | 12.3 |

2.3 Fatty Acid Analysis

The FA within total lipids was analyzed after saponification to account for esterified and nonesterified FAs in postmortem tissues. Chow diet, brain (temporal lobe) and liver tissue FAs were measured as FAME by GC/FID. FAME were prepared following a modification of the protocol by Metcalfe et al. [40, 41]. Briefly, tissue samples were homogenized at 100 mg tissue/mL in distilled water. Triheptadecanoin (100 μg; a triglyceride of C17:0; NuChek Prep, Elysian MN, USA,) was added to homogenates as an internal standard and the mixture exposed to boron trifluoride to form fatty acid methyl esters. FAME were separated using an Agilent J&W DB-23 column (30 m × 0.25 mm ID, film thickness 0.25 μm) on an HP 5890 GC with a flame ionization detector. The FAMEs were identified by their elution times relative to authenticated methylated FA, and quantities were determined by their abundance relative to the added internal standard. On the GC-FID system used for these studies, evaluation of equal weight FAME mixtures produced nearly identical response factors over a range of chain lengths and fatty acid masses indicating that the array of FAMEs generate equivalent peak area at equivalent mass. Approximately 23 and 24 FAs for brain and liver, respectively, were routinely identified and these accounted for ~99% of the FA peaks.

2.4 Calculations and Statistics

Individual FAs were calculated as percent of total FAs from the mass concentration of individual FAs (μmol FA/mg tissue) relative to the total FA concentration within the tissue and are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Linear regression analyses were performed testing differences in mass percent of each FA using SAS and STATA (SAS Institute Inc, Cary NC; STATA version 12.1, College Station, TX). Significance was set at the 0.05 level.

3. RESULTS

The nutrient and FA composition of the chow diets fed to the animals throughout their life span is shown in Table 2. The animals consumed a relatively low fat [13% of energy (en)] and high carbohydrate (68% en) diet compared to the modern Western diet (MWD; fat, ~35% en and carbohydrates ~50% en). However, composition of PUFAs is similar to that which would be found in a MWD [42, 43]. For example, n-6 and n-3 C18-PUFAs represented >97% of the total PUFA in the diet; consequently, the diets contained low concentrations of n-3 and n-6 preformed LC-PUFAs such as ARA and DHA. Additionally, the ratio of n-6 to n-3 PUFAs of 12.3 was consistent with that observed in the MWD.

Table 3 shows the FA composition (expressed as a mean % of total FAs) of the cortex of the temporal lobe from vervet monkeys ranging from birth to 3 months (during nursing) and 1 to >7 years old (on a chow diet). Major FAs within the cortex were palmitic acid (PA, C16:0), oleic acid (OA, C18:1n-9), arachidonic acid (ARA, C20:4n-6), adrenic acid (ADR, C22:4n-6) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, C22:6n-3). There were large age-dependent shifts within individual FAs with PA, ARA and ADR decreasing and OA and DHA increasing with the age of the animals. Overall, ratios of saturated and monounsaturated FA (SFA + MUFA) to PUFA decreased modestly throughout the examined lifespan of the animals, representing a modest overall increase in tissue PUFA concentrations. However, there was a marked (2.8 fold) age-dependent decrease in the overall ratio of n-6 to n-3 PUFAs and a similar reduction n-6 to n-3 LC-PUFAs reflecting a shift in the brain tissue towards n-3 LC-PUFAs.

Table 3.

Fatty acids in brain tissue of different age groups.

| BREAST FED BRAIN, % Mass | CHOW FED BRAIN, % Mass | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Age | Age | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Birth %(SD) | 1 Week %(SD) | 1–3 Months %(SD) | 6 Months- 1 Year %(SD) | 1–2 Years %(SD) | 2–3 Years %(SD) | 3–7 Years %(SD) | 7+ Years %(SD) | p-value (Δ 0–3 Months) | p-value (Δ ≥6 Months) | p-value (Δ lifespan) | |

| Fatty Acids | n=5 | n=4 | n=14 | n=6 | n=10 | n=4 | n=2 | n=5 | |||

| C14:0 | 1.0 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.0) | 0.3 (0.0) | 0.3 (0.0) | 0.3 (0.0) | < 0.0001 | 0.077 | < 0.0001 |

| C16:0 [PA] | 26.5 (0.3) | 25.1 (0.8) | 24.3 (0.4) | 21.9 (0.3) | 21.8 (0.4) | 23.8 (3.6) | 22.3 (0.6) | 21.5 (0.5) | < 0.0001 | 0.28 | < 0.0001 |

| C16:1 | 1.2 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.0) | 0.4 (0.0) | 0.4 (0.0) | 0.5 (0.0) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| C18:0 | 20.3 (0.2) | 21.0 (0.7) | 21.1 (0.2) | 22.2 (0.3) | 22.2 (0.5) | 24.9 (5.2) | 21.2 (0.2) | 21.8 (0.8) | < 0.0001 | 0.29 | < 0.0001 |

| C18:1 n-9 [OA] | 10.3 (0.3) | 11.0 (0.3) | 11.2 (0.3) | 12.3 (0.2) | 13.5 (0.7) | 13.8 (2.6) | 13.5 (0.8) | 14.4 (0.8) | < 0.0001 | 0.002 | < 0.0001 |

| C18:1 n-7 | 3.7 (0.2) | 3.5 (0.0) | 3.4 (0.1) | 3.6 (0.0) | 4.1 (0.4) | 4.4 (0.9) | 4.7 (0.1) | 4.9 (0.3) | 0.0007 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| C18:2 n-6 [LA] | 0.6 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.6 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.0) | 1.1 (0.0) | < 0.0001 | 0.14 | 0.087 |

| C18:3 n-6 [GLA] | 0.2 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.0) | 0.50 | 0.45 | 0.15 |

| C18:3 n-3 [ALA] | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | - | - | - | - | - | 0.13 | - | 0.16 |

| C18:4 n-3 [SDA] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C20:0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C20:1 n-9 | 0.2 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.0) | 0.3 (0.0) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.003 | 0.013 | < 0.0001 |

| C20:2 n-6 | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.0) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.0) | 0.3 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.0) | 0.3 (0.0) | 0.3 (0.0) | < 0.0001 | 0.26 | < 0.0001 |

| C20:3 n-6 [DGLA] | 1.1 (0.1) | 1.3 (0.0) | 1.4 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | < 0.0001 | 0.15 | 0.001 |

| C20:4 n-6 [ARA] | 13.5 (0.4) | 13.3 (0.6) | 12.5 (0.9) | 11.0 (0.3) | 9.6 (0.9) | 8.5 (3.1) | 8.3 (0.4) | 8.0 (0.6) | 0.0004 | < 0.0001 | 0.0002 |

| C20:4 n-3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C20:5 n-3 [EPA] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C22:0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C22:1 n-9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C22:4 n-6 [ADR] | 6.9 (0.4) | 6.9 (0.2) | 6.3 (0.4) | 6.2 (0.3) | 4.5 (0.6) | 1.9 (2.9) | 4.5 (0.6) | 1.9 (2.7) | 0.006 | 0.004 | < 0.0001 |

| C22:5 n-6 | 2.6 (0.4) | 2.5 (0.5) | 2.2 (0.3) | 1.5 (0.4) | 2.9 (0.5) | 3.9 (2.6) | 1.0 (0.1) | 3.3 (2.1) | 0.039 | 0.13 | 0.29 |

| C22:5 n-3 [DPA] | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.0) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.0) | 0.3 (0.0) | < 0.0001 | 0.53 | 0.72 |

| C22:6 n-3 [DHA] | 11.2 (0.5) | 11.6 (0.4) | 13.9 (1.8) | 17.2 (0.7) | 17.0 (1.3) | 15.2 (7.6) | 20.6 (1.8) | 19.8 (1.3) | < 0.0001 | 0.001 | < 0.0001 |

| C24:1 n-9 | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.04 (0.1) | 0.0 (0.0) | - | - | - | - | - | 0.62 | - | 0.21 |

|

| |||||||||||

| (SFA+MUFA)/PUFA | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 2.3 | < 0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.28 |

| Total n-6/n-3 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| n-6/n-3 LC-PUFA | 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

Cortex samples (n=50) were obtained from the archived Vervet tissues and analyzed for total fatty acid content as described in Methods. Data are expressed as mean % mass, (SD) of total fatty acids. Linear regression p-values are listed for the time span of both nursing and chow feeding, in addition to the entire lifespan. Ratios representing fatty acid intake and metabolism are also included. Fatty acids of interest included palmitic acid (PA), oleic acid (OA), linoleic acid (LA), gamma -linoleic acid (GLA), alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), stearodonic acid (SDA), dihomo-gamma-linolenic Acid (DGLA), arachidonic acid (ARA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), adrenic acid (ADR), docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA).

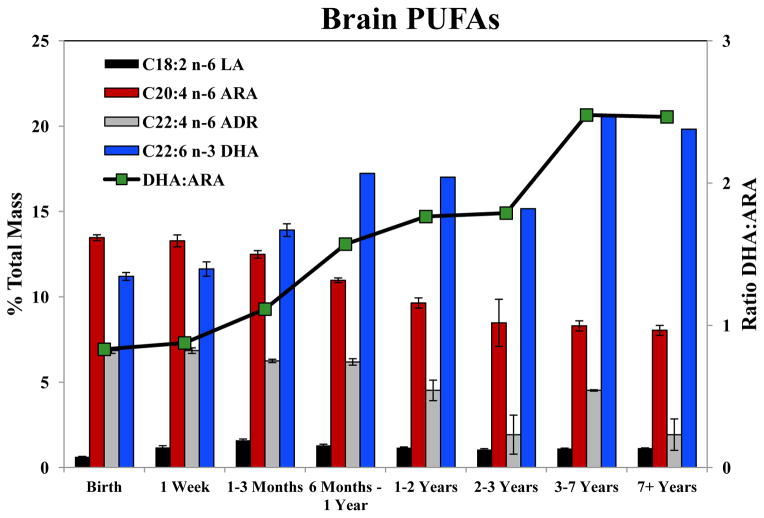

The levels (expressed as % of total) of the major n-6 and n-3 PUFAs within brain tissue across the different age categories are shown in Figure 1. There was a striking reduction in the proportion of n-6 LC-PUFAs, ARA and ADR concomitantly, with an increase in DHA in the brain tissue during the first 3 years. ARA comprises 13.5% of total FAs at birth, and remains relatively constant ~8% from 3–8 years of age. The elongation product of ARA, ADR, decreased from 6.9% to 1.9% from the youngest to the oldest age group. In contrast, the major n-3 LC-PUFA, DHA represented 11.2% of FAs at birth, increased to 20.6 % in the 3–7 year group, and remained at that level in older animals. The major PUFAs in the chow diets of the animals, LA and ALA, represented small proportions of the total FAs within the cortex at all ages (Figure 2 and Table 3). While these data showed marked alterations in the proportion of LC-PUFAs when expressed as a % of total FAs within the tissues, it was unclear whether these changes actually represented alterations in concentrations of both DHA and ARA within the cortex. Consequently, μmol quantities of these LC-PUFAs were determined and standardized to mg of cortical tissue.

Figure 1. Levels and ratios of select PUFAs in brain tissue.

PUFA levels are expressed as % of total mass and the ratio of DHA:ARA in brain tissue as a functions of animal age.

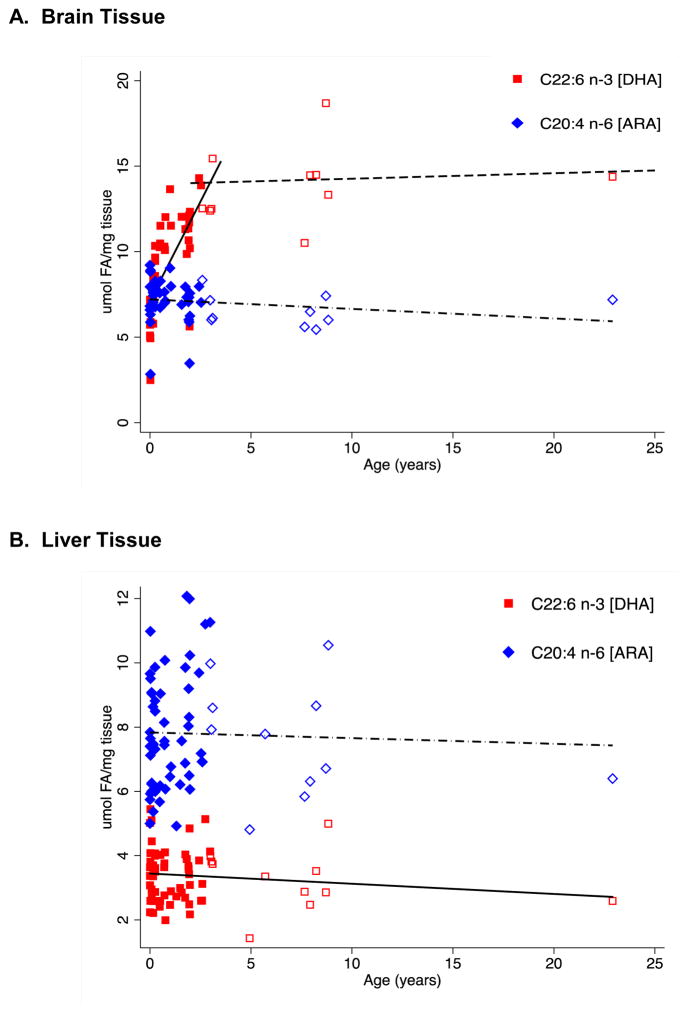

Figure 2. Mass concentration (μmol/mg tissue) of ARA and DHA in (A) brain tissue and (B) liver tissue in Vervet monkeys.

Linear regressions are shown for brain (ARA: R2=0.031, p=0.206; DHA: R2=0.539, p<0.0001 for Age≤3, filled markers; and R2=0.0071, p=0.843 for Age>3 years, unfilled markers) and liver (ARA: R2=0.0012, p=0.788; DHA: R2=0.017, p=0.295). Equations for linear regressions are shown in Table 5.

Figure 2 shows the concentrations of DHA and ARA in the cortex of individual animals. These data clearly point out that DHA accumulates in the cortex of these animals throughout their early lifespan with approximately 5 μmol/mg tissue at birth and increasing 3-fold to approximately 15 μmol/mg tissue in the oldest animals. Moreover, our linear regressions revealed that the rate of DHA accumulation pre-puberty (i.e. age ≤3 years) was 2.32 μmol/mg per year (95% CI: 1.66, 2.98) compared to 0.03 μmol/mg per year (95% CI: −0.35, 0.41) after the age of 3 years (Table 5). There were no statistically significant changes in the concentration of ARA, remaining at 6–8 μmol/mg tissue during the animals’ entire lifespan.

Table 5.

Linear regressions for DHA and ARA levels in brain and liver tissues.

| Fatty Acid (umol/mg) | Brain Tissue | Liver Tissue | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20:4n6 [ARA] | 7.21–0.055X | 7.83–0.018X | |

| 22:6n3 [DHA] | 8.81+0.508X*** | 3.44–0.032X | |

| Fatty Acid (umol/mg) | Age ≤ 3 years | Age > 3 years | |

| 22:6n3 [DHA] | 7.13+2.32X*** | 13.95+0.03X | |

Age is treated as an independent variable in the linear regression. The linear regression for DHA from brain tissue was further divided into subjects with ages ≤ 3 and >3 years, since Vervet monkeys reach puberty at 3 years, and this clearly shows two different rates of DHA accumulation over time as illustrated in Figure 2A.

p<0.0001)

The FA composition across the life span was next examined in the liver (Table 4). The liver is the tissue most associated with the biosynthesis of LC-PUFAs that are subsequently released into circulation. LC-PUFAs comprised a much lower percentage of total FAs within the liver. In contrast, the liver contained much higher levels of 18C-PUFAs. The FA composition of the liver (after nursing) mirrored the content of dietary FAs (Tables 2 and 4). There was a consistent increase in all PUFAs between birth and 1 week in conjunction with nursing. This is reflected by a 1.9-, 1.8- and 1.7- fold increase in ARA, DHA and LA, respectively. With the exception of stearic acid (1.9-fold increase), other FA levels remained relatively stable after nursing.

Table 4.

Fatty acids (expressed as % of total) in liver tissue in different age groups

| BREAST FED LIVER, % Mass | CHOW FED LIVER, % Mass | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Age | Age | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Fatty Acids | Birth %(SD) | 1 Week %(SD) | 1–3 Months %(SD) | 6 Months- 1 Year %(SD) | 1–2 Years %(SD) | 2–3 Years %(SD) | 3–7 Years %(SD) | 7+ Years %(SD) | p-value (Δ 0–3 Months) | p-value (Δ ≥6 Months) | p-value (Δ lifespan) |

| n=5 | n=5 | n=15 | n=8 | n=12 | n=7 | n=3 | n=5 | ||||

| C14:0 | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | < 0.0001 | 0.00009 | 0.018 |

| C16:0 [PA] | 30.5 (1.8) | 21.6 (1.2) | 20.3 (1.4) | 18.1 (0.7) | 18.7 (0.9) | 20.4 (1.3) | 22.4 (2.8) | 24.6 (1.5) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.0002 |

| C16:1 | 4.8 (1.0) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.2) | < 0.0001 | 0.0003 | < 0.0001 |

| C18:0 | 10.2 (1.2) | 18.2 (0.8) | 19.8 (1.9) | 21.3 (1.1) | 21.1 (0.5) | 20.0 (2.9) | 19.1 (2.7) | 20.2 (0.5) | < 0.0001 | 0.058 | < 0.0001 |

| C18:1 n-9 [OA] | 23.4 (1.7) | 10.1 (1.8) | 8.5 (1.4) | 8.1 (1.2) | 9.5 (1.1) | 9.7 (0.9) | 10.2 (2.3) | 8.8 (1.0) | < 0.0001 | 0.066 | < 0.0001 |

| C18:1 n-7 | 3.6 (0.6) | 2.5 (0.3) | 2.1 (0.6) | 2.1 (0.2) | 2.0 (0.3) | 2.1 (0.5) | 2.4 (0.3) | 2.3 (0.3) | < 0.0001 | 0.35 | < 0.0001 |

| C18:2 n-6 [LA] | 12.3 (2.0) | 17.7 (1.5) | 20.8 (1.0) | 23.6 (1.5) | 23.1 (1.1) | 22.7 (1.2) | 21.0 (2.5) | 21.7 (1.1) | < 0.0001 | 0.003 | < 0.0001 |

| C18:3 n-6 [GLA] | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.17 | 0.47 | 0.41 |

| C18:3 n-3 [ALA] | 0.23 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.3(0.3) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.89 | 0.69 | 0.15 |

| C18:4 n-3 [SDA] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C20:0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C20:1 n-9 | 0.1 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.13 | 0.43 | < 0.0001 |

| C20:2 n-6 | 0.4 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.1) | < 0.0001 | 0.12 | < 0.0001 |

| C20:3 n-6 [DGLA] | 1.2 (0.3) | 4.5 (0.8) | 3.6 (0.8) | 3.6 (1.0) | 4.1 (1.1) | 3.5 (0.6) | 3.6 (0.6) | 2.6 (1.3) | 0.003 | 0.14 | 0.070 |

| C20:4 n-6 [ARA] | 7.1 (1.1) | 13.5 (1.6) | 13.1 (0.7) | 12.2 (1.3) | 11.2 (0.7) | 10.9 (1.0) | 10.3 (0.2) | 9.5 (0.5) | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.42 |

| C20:4 n-3 | 0.03 (0.0) | 0.04 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.27 |

| C20:5 n-3 [EPA] | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.0) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.0) | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.036 | 0.030 | < 0.0001 |

| C22:0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C22:1 n-9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C22:4 n-6 [ADR] | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.016 | 0.022 | < 0.0001 |

| C22:5 n-6 | 0.6 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.70 | 0.38 | < 0.0001 |

| C22:5 n-3 [DPA] | 0.5 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.3) | 1.3 (0.13 | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) | < 0.0001 | 0.64 | 0.011 |

| C22:6 n-3 [DHA] | 3.7 (0.7) | 6.9 (1.2) | 6.7 (1.3) | 5.4 (1.0) | 4.8 (0.6) | 4.7 (0.5) | 5.0 (0.2) | 4.5 (0.7) | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.040 |

| C24:1 n-9 | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.01 (0.0) | - | - | - | - | - | 0.76 | - | 0.51 |

|

| |||||||||||

| (SFA+MUFA)/PUFA | 2.8 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Total n-6/n-3 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 5.7 | 6.3 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 5.8 | 0.50 | 0.96 | < 0.0001 |

| n-6/n-3 LC-PUFA | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 0.81 | 0.54 | 0.015 |

Liver samples (n=60) were obtained from the tissue bank and analyzed for total fatty acid content as described in Methods. Data are expressed as mean %mass, (SD) of total fatty acids. Linear regression p-values are listed for the time span of both nursing and chow feeding, in addition to the entire lifespan. Ratios representing fatty acid intake and metabolism are also included. Abbreviations as in Table 3.

4. DISCUSSION

It has long been recognized that the ingestion of LC-PUFAs such as DHA, especially prenatally during the third trimester of pregnancy and postnatal through the first two years of life, is critical to proper brain and eye development and function in humans. It is during this period of time that PUFAs such as DHA and ARA accumulate in the central nervous system [44]. This “DHA accretion spurt” has been associated with a marked increase in Δ-6 desaturase (enzymatic product of FADS1) activity in late embryonic and postnatal rodent brain [30, 32, 45]. However, less is known about the accretion of these FAs in the brain during adolescence and throughout adulthood.

The current study has addressed the dynamics of LC-PUFA levels in cortical brain and liver tissues in nonhuman primates (i.e. vervet monkeys) from birth through early adulthood. This animal model offered significant advantages including the capacity to control diet and other environmental factors, to limit genetic factors that could influence LC-PUFA metabolism, and the ability to sample tissues (i.e. liver) that could impact brain FA levels throughout the animals’ early lifespan [46]. These data strongly support the concept that there is a robust accretion of DHA in cortical brain tissue in these animals up until 3 years of age. In captivity, vervet females reach puberty at ~2.5 years of age and achieve full adult size by the age of 4. Male vervets reach puberty at 3 years of age and complete growth by 5 years [39]. During the same period of time, concentrations of ARA and ADR remained relatively constant. These changes result in marked alterations in the ratios of n-3 to n-6 LC-PUFA found in the cortex. In contrast, the PUFA composition of the liver closely represented the PUFA levels in the diets of the animals. LA was the primary PUFA in liver tissue at all ages, and LC-PUFAs represented small proportions of the total PUFAs. Importantly, there was no evidence for large age-dependent changes in LC-PUFA levels or ratios in the liver.

These data raise the important question of the source of DHA that accumulates in the brain. Clearly, there are only small quantities of pre-formed DHA in the diet and the analysis of the PUFA composition of the liver suggests that the biosynthetic capacity of the liver to produce LC-PUFAs is not responsible for the changes in DHA observed in the brain. Brain specific mechanism(s) such as changes in LC-PUFA biosynthesis or transporter-specific incorporation rates across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) over time in the primate brain are potential candidates for the marked alterations in the levels and ratios of DHA and ARA. For example, movement of DHA across the blood–brain barrier recently has been shown to require specific transporters, such as Mfsd2a for 2-docosahexaenoyl lysophosphotidylcholine [33–35]

Our findings correspond with previous studies in rhesus monkeys that indicate DHA accumulates in brain tissue during early development [4]. Another study in baboon neonates demonstrated that DHA and ARA are richly distributed into numerous brain gray matter structures, especially brain stem, basal ganglia, limbic regions, thalamus, and midbrain [47]. Interestingly in neonates not receiving DHA, DHA levels are reduced in most of these brain regions. In contrast, ARA levels in all structures were relative resistant to changes in dietary ARA. The observation that DHA levels change and ARA levels remain relatively constant is consistent with data in the current study. Additionally, both studies suggest that levels of the two primary LC-PUFAs, DHA and ARA within the brain, are regulated by distinct mechanisms.

Several lines of evidence indicate that n-3 LC-PUFA deficiencies may play an adverse role in neurodevelopment and childhood behavior [7]. Numerous studies report associations between reduced DHA and/or altered ratios of n-6 to n-3 ratios in both peripheral blood components (as well as postmortem brain tissue) and psychiatric illnesses, mood and developmental disorders and dementia [13, 19–23]. Depressive disorders are perhaps the most studied with regard to n-3 LC-PUFA composition. A recent meta-analysis of 14 studies concluded that patients with depression had significantly lower n-3 LC-PUFAs in blood compartments than control subjects [21]. McNamara and colleagues found that postmortem orbitofrontal cortex from patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder all had significantly lower amounts of DHA when compared to control subjects [22]. With regard to developmental disorders such as ADHD in childhood/adolescence, a recent meta-analysis of nine studies (n=586) found significantly lower blood levels of n-3 LC-PUFAs in ADHD children versus controls and concluded that n-3 LC-PUFAs are reduced in children with ADHD [24].

Importantly, several studies have also shown that supplementation with n-3 LC-PUFA or combinations of n-3/n-6 PUFAs improve symptoms in ADHD, depression and learning difficulties [15, 24, 48–51]. For example, Amminger and colleagues demonstrated the potential for n-3 LC-PUFAs to prevent adolescents at high risk for psychosis from transitioning to a disorder [48]. A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study with n-3 LC-PUFAs in children showed the experimental group to be superior to placebo on several depression scale measures [49]. Recent meta-analyses suggest improvement of composite ADHD symptoms in n-3 LC-PUFA treatment groups as compared to placebo controls [15, 24, 50, 51].

Our data are consistent with previous reports that DHA levels increase and n-6 to n-3 LC-PUFA ratios change dramatically in the cortical brain tissue from childhood to adolescence [26, 27]. If levels of these FAs are critical to basic neurobiology such as the neuronal growth, survival, synaptogenesis and neurotransmitter release as has been reported, then a disruption in the rapidly changing milieu of LC-PUFA homeostasis could have important biological and clinical effects [7, 12, 52–57]. The incidences of several childhood psychiatric and developmental disorders including depression, ADHD and ASD have increased over the past two decades. Such increases suggest that environmental factors (such as diet) maybe playing an important role. Perhaps the largest change as a result of the MWD is the dramatic elevation in the dietary n-6 PUFAs in only 50 years [58, 59]. This increase has altered the balance of PUFAs entering the biosynthetic pathway leading to reductions in DHA and alterations in n-6 to n-3 PUFA ratios in human tissues such as the brain [58]. The current data together with an earlier human study [27] reveal that concentrations of DHA rapidly accumulate (~3-fold) in the cortex of the brain from childhood through early adulthood suggesting this may be a critical period of n-3 LC-PUFA biosynthesis and/or transport. Consequently, this time period may represent an important opportunity to alter the intake of PUFAs (either from the diet or utilizing supplements) in a fashion that will have meaningful impact on the incidence and severity of child/adolescent psychiatric and developmental disorders.

Highlights.

Levels of the n-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA), docosahexaenoic acid, increased dramatically in the cortex of vervet monkeys from birth to puberty.

Marked changes in the ratios of n-6 to n-3 PUFAs occurred in the cortex during this same time period.

This period of DHA accretion is concurrent with the symptomatic onset of numerous psychiatric and developmental disorders in humans.

These data raise the question of whether this is a period where inadequate dietary n-3 PUFAs impacts brain development.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, P50 AT002782 (F.H. Chilton) and RR019963/OD010965 (J. R. Kaplan). We would also like to acknowledge the grant that supported the tissue collections: R37 MH060233 (D. Geschwind)

Footnotes

6. Financial Disclosures

Dr. Chilton is a paid consultant for Eagle Wellness, LLC. This information has been disclosed to Wake Forest School of Medicine and outside sponsors, as appropriate, and is institutionally managed. All other authors declare no competing or conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gibson RA, Muhlhausler B, Makrides M. Conversion of linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acid to long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFAs), with a focus on pregnancy, lactation and the first 2 years of life. Matern Child Nutr. 2011;7(Suppl 2):17–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uauy R, Dangour AD. Nutrition in brain development and aging: role of essential fatty acids. Nutr Rev. 2006;64:S24–33. doi: 10.1301/nr.2006.may.s24-s33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neuringer M, Anderson GJ, Connor WE. The essentiality of n-3 fatty acids for the development and function of the retina and brain. Annu Rev Nutr. 1988;8:517–41. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.08.070188.002505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neuringer M, Connor WE, Lin DS, Barstad L, Luck S. Biochemical and functional effects of prenatal and postnatal omega 3 fatty acid deficiency on retina and brain in rhesus monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:4021–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.4021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novak EM, Dyer RA, Innis SM. High dietary omega-6 fatty acids contribute to reduced docosahexaenoic acid in the developing brain and inhibit secondary neurite growth. Brain Res. 2008;1237:136–45. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuipers RS, Luxwolda MF, Offringa PJ, Boersma ER, Dijck-Brouwer DA, Muskiet FA. Fetal intrauterine whole body linoleic, arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acid contents and accretion rates. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2012;86:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gow RV, Hibbeln JR. Omega-3 fatty acid and nutrient deficits in adverse neurodevelopment and childhood behaviors. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2014;23:555–90. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourre JM. Roles of unsaturated fatty acids (especially omega-3 fatty acids) in the brain at various ages and during ageing. J Nutr Health Aging. 2004;8:163–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Elst K, Bruining H, Birtoli B, Terreaux C, Buitelaar JK, Kas MJ. Food for thought: dietary changes in essential fatty acid ratios and the increase in autism spectrum disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;45:369–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James S, Montgomery P, Williams K. Omega-3 fatty acids supplementation for autism spectrum disorders (ASD) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD007992. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007992.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gow RV, Sumich A, Vallee-Tourangeau F, Angus CM, Ghebremeskel K, Bueno AA, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids are related to abnormal emotion processing in adolescent boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2013;88:419–29. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bondi CO, Taha AY, Tock JL, Totah NK, Cheon Y, Torres GE, et al. Adolescent behavior and dopamine availability are uniquely sensitive to dietary omega-3 fatty acid deficiency. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SW, Schafer MR, Klier CM, Berk M, Rice S, Allott K, et al. Relationship between membrane fatty acids and cognitive symptoms and information processing in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2014;158:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer BJ, Grenyer BF, Crowe T, Owen AJ, Grigonis-Deane EM, Howe PR. Improvement of major depression is associated with increased erythrocyte DHA. Lipids. 2013;48:863–8. doi: 10.1007/s11745-013-3801-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillies D, Sinn J, Lad SS, Leach MJ, Ross MJ. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD007986. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007986.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogers LK, Valentine CJ, Keim SA. DHA supplementation: current implications in pregnancy and childhood. Pharmacol Res. 2013;70:13–9. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lattka E, Klopp N, Demmelmair H, Klingler M, Heinrich J, Koletzko B. Genetic variations in polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolism--implications for child health? Ann Nutr Metab. 2012;60(Suppl 3):8–17. doi: 10.1159/000337308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Standl M, Lattka E, Stach B, Koletzko S, Bauer CP, von BA, et al. FADS1 FADS2 gene cluster, PUFA intake and blood lipids in children: results from the GINIplus and LISAplus studies. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37780. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horrobin DF, Manku MS, Hillman H, Iain A, Glen M. Fatty acid levels in the brains of schizophrenics and normal controls. Biol Psychiatry. 1991;30:795–805. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(91)90235-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Assies J, Lieverse R, Vreken P, Wanders RJ, Dingemans PM, Linszen DH. Significantly reduced docosahexaenoic and docosapentaenoic acid concentrations in erythrocyte membranes from schizophrenic patients compared with a carefully matched control group. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:510–22. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00986-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin PY, Huang SY, Su KP. A meta-analytic review of polyunsaturated fatty acid compositions in patients with depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:140–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McNamara RK, Hahn CG, Jandacek R, Rider T, Tso P, Stanford KE, et al. Selective deficits in the omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid in the postmortem orbitofrontal cortex of patients with major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens LJ, Zentall SS, Deck JL, Abate ML, Watkins BA, Lipp SR, et al. Essential fatty acid metabolism in boys with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;62:761–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.4.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawkey E, Nigg JT. Omega-3 fatty acid and ADHD: blood level analysis and meta-analytic extension of supplementation trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34:496–505. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNamara RK, Vannest JJ, Valentine CJ. Role of perinatal long-chain omega-3 fatty acids in cortical circuit maturation: Mechanisms and implications for psychopathology. World J Psychiatry. 2015;5:15–34. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v5.i1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez M, Mougan I. Fatty acid composition of human brain phospholipids during normal development. J Neurochem. 1998;71:2528–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71062528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carver JD, Benford VJ, Han B, Cantor AB. The relationship between age and the fatty acid composition of cerebral cortex and erythrocytes in human subjects. Brain Res Bull. 2001;56:79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00551-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sprecher H. Biochemistry of essential fatty acids. Prog Lipid Res. 1981;20:13–22. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(81)90009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park HG, Park WJ, Kothapalli KS, Brenna JT. The fatty acid desaturase 2 (FADS2) gene product catalyzes Delta4 desaturation to yield n-3 docosahexaenoic acid and n-6 docosapentaenoic acid in human cells. FASEB J. 2015 doi: 10.1096/fj.15-271783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitson AP, Smith TL, Marks KA, Stark KD. Tissue-specific sex differences in docosahexaenoic acid and Delta6-desaturase in rats fed a standard chow diet. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012;37:1200–11. doi: 10.1139/h2012-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell RW, Hatch GM. Fatty acid transport into the brain: of fatty acid fables and lipid tails. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2011;85:293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitson AP, Stark KD, Duncan RE. Enzymes in brain phospholipid docosahexaenoic acid accretion: a PL-ethora of potential PL-ayers. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2012;87:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernoud N, Fenart L, Moliere P, Dehouck MP, Lagarde M, Cecchelli R, et al. Preferential transfer of 2-docosahexaenoyl-1-lysophosphatidylcholine through an in vitro blood-brain barrier over unesterified docosahexaenoic acid. J Neurochem. 1999;72:338–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen LN, Ma D, Shui G, Wong P, Cazenave-Gassiot A, Zhang X, et al. Mfsd2a is a transporter for the essential omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid. Nature. 2014;509:503–6. doi: 10.1038/nature13241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hachem M, Geloen A, Van AL, Foumaux B, Fenart L, Gosselet F, et al. Efficient docosahexaenoic acid uptake by the brain from a structured phospholipid. Mol Neurobiol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bazinet RP, Laye S. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their metabolites in brain function and disease. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2014;15:771–85. doi: 10.1038/nrn3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaduce TL, Chen Y, Hell JW, Spector AA. Docosahexaenoic acid synthesis from n-3 fatty acid precursors in rat hippocampal neurons. J Neurochem. 2008;105:1525–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naughton JM. Supply of polyenoic fatty acids to the mammalian brain: the ease of conversion of the short-chain essential fatty acids to their longer chain polyunsaturated metabolites in liver, brain, placenta and blood. Int J Biochem. 1981;13:21–32. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(81)90132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kavanagh K, Fairbanks LA, Bailey JN, Jorgensen MJ, Wilson M, Zhang L, et al. Characterization and heritability of obesity and associated risk factors in vervet monkeys. Obesity. 2007;15:1666–74. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Metcalfe LDS, AA Rapid preparation nof fatty acid esters from lipids for gas chromatographic analysis. Anal Chem. 1966;38:514–5. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weaver KL, Ivester P, Seeds MC, Case LD, Arm J, Chilton FH. Effect of dietary fatty acids on inflammatory gene expression in healthy humans. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:15400–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.004861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bradbury J. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA): an ancient nutrient for the modern human brain. Nutrients. 2011;3:529–54. doi: 10.3390/nu3050529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chilton FH, Murphy RC, Wilson BA, Sergeant S, Ainsworth H, Seeds MC, et al. Diet-Gene Interactions and PUFA Metabolism: A Potential Contributor to Health Disparities and Human Diseases. Nutrients. 2014;6:1993–2022. doi: 10.3390/nu6051993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Green P, Yavin E. Mechanisms of docosahexaenoic acid accretion in the fetal brain. J Neurosci Res. 1998;52:129–36. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980415)52:2<129::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dobbing J, Sands J. Comparative aspects of the brain growth spurt. Early Hum Dev. 1979;3:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(79)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jasinska AJ, Schmitt CA, Service SK, Cantor RM, Dewar K, Jentsch JD, et al. Systems biology of the vervet monkey. ILAR J. 2013;54:122–43. doi: 10.1093/ilar/ilt049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Diau GY, Hsieh AT, Sarkadi-Nagy EA, Wijendran V, Nathanielsz PW, Brenna JT. The influence of long chain polyunsaturate supplementation on docosahexaenoic acid and arachidonic acid in baboon neonate central nervous system. BMC Med. 2005;3:11. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amminger GP, Schafer MR, Papageorgiou K, Klier CM, Cotton SM, Harrigan SM, et al. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids for indicated prevention of psychotic disorders: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:146–54. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nemets H, Nemets B, Apter A, Bracha Z, Belmaker RH. Omega-3 treatment of childhood depression: a controlled, double-blind pilot study. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1098–100. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bloch MH, Qawasmi A. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for the treatment of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptomatology: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:991–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sonuga-Barke EJ, Brandeis D, Cortese S, Daley D, Ferrin M, Holtmann M, et al. Nonpharmacological interventions for ADHD: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of dietary and psychological treatments. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:275–89. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12070991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McNamara RK, Carlson SE. Role of omega-3 fatty acids in brain development and function: potential implications for the pathogenesis and prevention of psychopathology. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2006;75:329–49. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carlson SE. Docosahexaenoic acid and arachidonic acid in infant development. Semin Neonatol. 2001;6:437–49. doi: 10.1053/siny.2001.0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levant B, Radel JD, Carlson SE. Decreased brain docosahexaenoic acid during development alters dopamine-related behaviors in adult rats that are differentially affected by dietary remediation. Behav Brain Res. 2004;152:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sublette ME, Galfalvy HC, Hibbeln JR, Keilp JG, Malone KM, Oquendo MA, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acid associations with dopaminergic indices in major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17:383–91. doi: 10.1017/S1461145713001399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paus T. How environment and genes shape the adolescent brain. Horm Behav. 2013;64:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McNamara RK, Sullivan J, Richtand NM, Jandacek R, Rider T, Tso P, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid deficiency augments amphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization in adult DBA/2J mice: relationship with ventral striatum dopamine concentrations. Synapse. 2008;62:725–35. doi: 10.1002/syn.20542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hibbeln JR, Nieminen LR, Blasbalg TL, Riggs JA, Lands WE. Healthy intakes of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids: estimations considering worldwide diversity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1483S–93S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1483S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blasbalg TL, Hibbeln JR, Ramsden CE, Majchrzak SF, Rawlings RR. Changes in consumption of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in the United States during the 20th century. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:950–62. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.006643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]