Abstract

Oligodendrocytes derived in the laboratory from stem cells have been proposed as a treatment for acute and chronic injury to the central nervous system. Platelet-derived growth factor-receptor alpha (PDGFRα) signaling is known to regulate oligodendrocyte precursor cell numbers both during development and adulthood. Here, we analyze the effects of PDGFRα signaling on central nervous system (CNS) stem cell-enriched cultures. We find that AC133 selection for CNS progenitors acutely isolated from the fetal cortex enriches for PDGF-AA responsive cells. PDGF-AA treatment of FGF2-expanded CNS stem cell-enriched cultures increases nestin+ cell number, viability, proliferation, and glycolytic rate. We show that a brief exposure to PDGF-AA rapidly and efficiently permits the derivation of O4+ oligodendrocyte-lineage cells from CNS stem cell-enriched cultures. The derivation of oligodendrocyte-lineage cells demonstrated here may support the effective use of stem cells in understanding fate choice mechanisms and the development of new therapies targeting this cell type.

Keywords: oligodendrocytes, multipotent stem cells, platelet-derived growth factor, glycolysis, extracellular signal-regulated MAP kinases, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

Introduction

Multipotent stem cells that generate neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes can be readily derived from the fetal and adult brain of many mammals 1–3. Neural stem cells can also be efficiently generated from embryonic stem (ES) cells 4, 5. Stem cells are sensitive to cytokines and ligands for the CNTF/LIFR family are thought to promote astrocytic fates vitro 6. As a consequence, the transition from multipotent precursor to astrocytic precursor and the subsequent control of these restricted progenitors has been intensely studied 7–10. Stem cells are also a source of oligodendrocytes that have been used to treat demyelinating disease in animal models, and oligodendrocytes derived from human ES cells may provide new cell therapies in spinal cord injury11–13.

Although transplantation shows that functional oligodendrocytes can be generated from precursors that expand in tissue culture, no study explicitly defines the transition from neural stem cell to oligodendrocyte precursor. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) was initially identified because of its role in the proliferation of glial cells and its oncogenic function in sarcoma virus 14–16. The subsequent identification of the PDGF receptor has had an important role in defining membrane events that trigger cell proliferation 17–19. PDGF and its receptors are expressed in several different cell types in the developing and adult CNS 20. PDGF ligands A, B, C, D occur as homodimers and as a heterodimer (AB) and bind two tyrosine kinase cell surface receptors, PDGFRα and PDGFRβ. Most of the ligands (AA, AB, BB, CC) bind PDGFRα while a subset (BB, DD) only bind PDGFRβ. In the CNS, PDGFRα is expressed by neuroepithelial cells as early as E8.5, retinal astrocytes, oligodendrocyte precursors, and neurogenic adult neural stem cells 21–25. In vitro and in vivo, PDGF-AA generated by astrocytes sustains the proliferation of oligodendrocyte precursors26–29. In the adult brain, oligodendrocyte density is controlled by co-operative effects of PDGF and FGF2 30. PDGF-AA generated by astrocytes supports oligodendrocyte precursor proliferation and promotes subsequent remyelination in a model of chronic demyelination31. In this manuscript, we report a one-step serum-free method to generate large numbers of oligodendrocyte precursors from midgestation telencephalic precursor cells in tissue culture. As neural stem cells can be generated from pluripotent ES and iPS cells, we can envisage a time when oligodendrocytes can be generated that carry any mouse or human genome4, 11, 12, 32. The rapid response to PDGF-AA, we report, may contribute to the wider use of oligodendroglial cells in drug development and disease models.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

CNS stem cell-enriched cultures were derived from CD-1 mouse embryos at embryonic day 13.5 (E13.5) (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) in serum-free DMEM/F12 media (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) with N2 supplement (expansion medium) and FGF2 (20 ng/ml, added daily, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), as previously described 6, 33. CNS stem cell-enriched cultures from passage 1 were plated at 5,000–25,000 cells/cm2. FGF2 was included throughout our experiments unless otherwise stated. To derive, propagate and expand oligodendrocyte precursors from E13.5 cortical cells or CNS stem cell-enriched cultures, cells were cultured in PDGF-AA (30 ng/ml, added daily, R&D Systems) without FGF2 (20 ng/ml) in expansion media. To rapidly induce oligodendrogliogenesis from CNS stem cell-enriched cultures, passage 1 stem cells were re-plated at 25,000 cells/cm2 in PDGF-AA containing medium for 12 h, and cultured in serum-free differentiation media consisting of Neurobasal media with B-27 supplement (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for a differentiation period of 4–5 d. To induce differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursors derived from CNS stem cell-enriched cultures or primary E13.5 embryonic cortical cells, PDGF-AA was withdrawn and expansion media was replaced with differentiation media.

Immunocytochemistry

Cultured CNS cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and processed as described 33, 34. Cells were stained with primary antibodies against the following proteins: A2B5 (mouse monoclonal, 1:500, Chemicon, Temecula, CA), NG2 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:100, Chemicon), O4 (mouse monoclonal, 1:50, Chemicon), BrdU (rat monoclonal, 1:400, Accurate, Westbury, NY), cleaved caspase-3 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:200, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), nestin (rabbit serum 130, 1:100, McKay Lab), Sox2 (goat polyclonal, 1:50, R&D Systems), PDGFRα (rabbit polyclonal, 1:500, Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA), Olig2 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:5000, kind gift of H. Takebayashi). Appropriate secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488 and 568, 1:200, Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) were applied and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (0.25 μg/ml, Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Images were captured, using fluorescent filters, with a Zeiss Axioplan microscope and Zeiss Axiocam HR camera (Carl Zeiss Inc, Thornwood, NY).

Magnetic affinity cell sorting for AC133 (prominin-1)

Dissociated E13.5 murine cortical cells were resuspended in 300 μl of N2 containing medium without FGF2 or PDGF-AA. 30 μl of prominin-coated beads (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA) were mixed with approx. 6–10 million cortical cells and incubated for 40 m at 6°C with occasional mixing by tapping the tube. At the end of incubation, cells were placed in MS columns (Miltenyi Biotech) and were washed using N2 medium without any added growth factor according to the protocol described by the supplier. After two washes, the column was removed from the magnet and eluted with 2 ml of N2 medium. Both eluted (AC133+) and unabsorbed (AC133-) cells were plated in fibronectin-coated, 24 well plates (Falcon) at 12.5 x 103 cells/cm2. Both groups were treated with PDGF-AA (30 ng/ml, R&D Systems) for 10 d. At days 0 (30 m following plating), 4, 7 and 10, cells were treated with Calcein AM in DMSO (Molecular Probes) at a final concentration of 2 μM. Plates treated with Calcein AM were returned to the incubator for 20 m, after which they were ready for imaging. Fluorescent images from these plates were acquired form nine predetermined fields within each well on an Opera system (Evotec Technologies, Hamburg, Germany), a high-speed automated confocal microscope. Cell counts were obtained from the images using Acapella image software (Evotec Technologies).

Measurement of glycolytic rate

CNS stem cell-enriched cultures were plated at 6.25 x 104 cells/cm2 and cultured for 24 h or 48 h, and treated as indicated in the Figure legends. Cells were then incubated in expansion media supplemented with 10 mM glucose and 20 μCi/ml [5-3H]glucose (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) at 37°C as previously described 35 with some modifications. After 1 h, an equal volume of 0.2 N HCl was added to stop the reaction. 3H2O was separated from unmetabolized [5-3H]glucose by evaporative diffusion of 3H2O in a sealed equilibration chamber. Samples were then analyzed with a scintillation counter, and readings were normalized by cell number.

Flow cytometry

Cells were plated at 3.12 x 104 cells/cm2 and cultured for 3 d, and treated as indicated in the Figure legends (growth factors added daily, media was not changed so that viable and nonviable cells could be analyzed). Adherent cells were passaged into suspension and combined with floating viable and nonviable cells and analyzed for viability based on propidium iodide exclusion. Flow cytometry and data analysis were performed using a FACScaliber system and CELLQuest-Pro software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

RNA Preparation and RT-PCR

Total RNA was prepared using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and samples were treated with DNase (DNA-free, Ambion, Austin, TX). 200 ng of RNA was reverse-transcribed using Superscript III (Invitrogen) with random primers. For semi-quantitative RT-PCR, cDNA was amplified for 30 cycles with Taq polymerase (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) using gene specific primers, and products were analyzed on ethidium bromide stained agarose gels. Primer sequences used were: Sox10, forward 5′-ATT CAG GCT CCG TCC AGA CAA GGC-3′, reverse 5′-ACC TCT GAT AGG TCT TGT TCC TCG G-3′; Cnp1, forward 5′-ACA GCG TGG CGA CTA GAC TGT GC-3′, reverse 5′-ACC TGG AGG TCT CTT TCC AAA GTA GC-3′; Actin, forward 5′-CTA GAC TTC GAG CAG GAG ATG GC-3′, reverse 5′-TCT GCA TCC TGT CAG CAA TGC C-3′.

Western blotting

Protein was harvested as described previously 33. Standardized protein was loaded on 4–12% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (both Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Primary antibodies include PDGFRα, PDGFβ (Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA), phospho-tyrosine742-PDGFRα (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), phospho-serine-473-Akt, Akt, phospho-threonine-202/tyrosine-204-Erk1/2 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), and tubulin (Sigma, St. Louis MO). Blots were probed with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:10,000, Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) followed by chemiluminescent reagent (1:2, Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Pharmacologic treatments

Unless otherwise stated, we used the following concentrations: LY294002 (10 μM), PD98059 (50 μM), rapamycin (1 μM) (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). For the effects of kinase inhibitors on activation of signaling pathways following PDGF-AA treatment, cells were pre-incubated for 1 h with inhibitor prior to PDGF-AA administration. Control cultures were treated with DMSO vehicle.

Statistical Analysis

In all experiments, mean ± s.d. or s.e.m. are presented as stated. Asterisks identify experimental groups significantly different from control groups by the Student’s T-test. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

CNS precursors express PDGFRα and respond to PDGF-AA

When dissociated murine E13.5 cortical cells are placed in culture with the growth factor FGF2, multipotent CNS stem cells proliferate as a homogenous monolayer that provides an excellent substrate to understand survival signaling and fate choice6, 33. To determine whether FGF2-expanded, multipotent CNS precursors are competent to respond to PDGF-AA, we assayed for the presence of PDGFRα, the PDGF receptor specific to PDGF-AA and known to be expressed on oligodendrocyte-lineage cells24 and adult neural stem cells36. Western blotting and immunostaining shows that cells in cultures enriched for CNS stem cells express PDGFRα as they expand in FGF2 (Fig 1A and D).

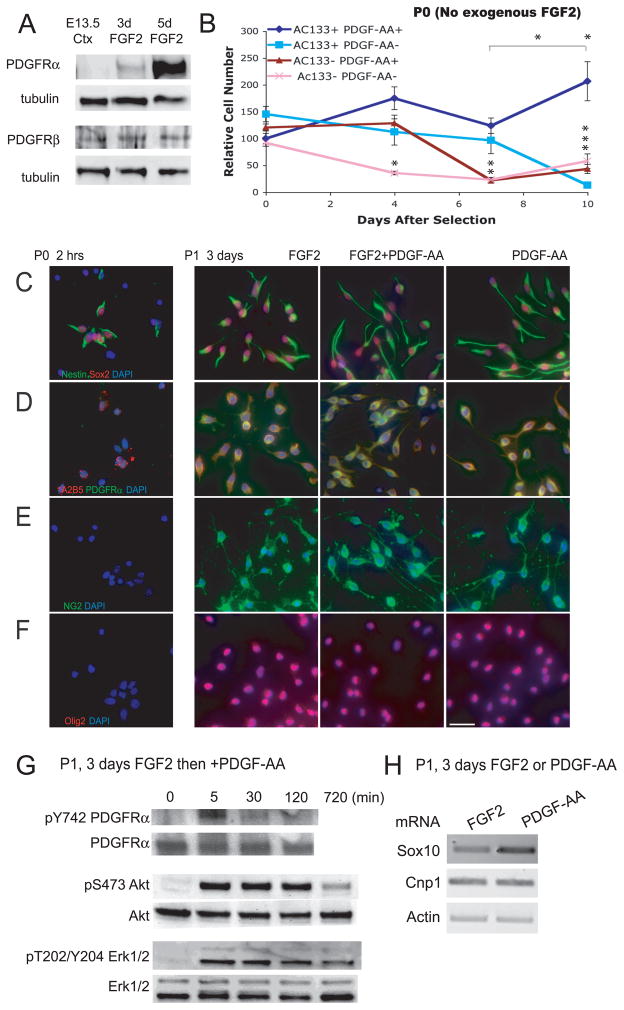

Figure 1. Fetal CNS stem cell-enriched cultures are PDGF-AA responsive: PDGF-AA treatment activates PI3K/Akt and MEK/Erk pathways but maintains expression of precursor markers.

(A) Western blot (WB) analysis of PDGFRs α and β in E13.5 lateral cortex, and after 3 and 5 day treatment with FGF2. (B) AC133 selection enriches for PDGF-AA responsive cells. Acutely dissected E13.5 cortical cells were sorted based on expression of AC133, and positively and negatively selected cells were cultured (plated at 12,500 cells/cm2) with or without PDGF-AA (no exogenous FGF2 was added) and cell number (mean ± s.e.m., n = 5 per timepoint, *p < 0.05) was measured at 0 (30 min after plating), 4, 7, and 10 d. (C,D,E,F) Passage 1, FGF2-expanded, CNS stem cells with treated with FGF2 alone, FGF2 + PDGF-AA, or switched from FGF2 to PDGF-AA alone for 3 d. Primary (Passage 0) E13.5 cortical cells, untreated with FGF2 or PDGF-AA, serve as controls. PDGF-AA treated cells maintained expression of several precursor markers, including (C) nestin (green), Sox2 (red); (D) A2B5 (red), PDGFRα (green); (E) NG2 (green); (F) Olig2 (red). All nuclei (B–F) were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 20 μm. (G) PDGF-AA causes phosphorylation of PDGFRα and rapid and sustained activation of MEK/Erk and PI3K/Akt pathways. (H) RT-PCR data for Sox10, Cnp1, and Actin mRNA after 3 d treatment of passage 1 CNS stem cells with FGF2 or PDGF-AA.

AC133 (also known as prominin-1) is a transmembrane glycoprotein expressed in stem cells of the hematopoietic and nervous systems3, 37, 38. To determine whether CNS progenitor cells acutely isolated from the fetal cortex respond to PDGF-AA, we used magnetic affinity cell sorting (MACS) to prospectively isolate AC133+ and AC133- fractions E13.5 murine cortical cells39. Following MACS sorting, AC133+ and AC133- embryonic cortical cells were cultured with or without PDGF-AA, in the absence of exogenous FGF2. The cells were plated at a relatively low density (12,500 cells/cm2) and cell number measured at 0 (30 minutes after plating), 4, 7, and 10 days (Fig 1B). At 1 week, large numbers of cells were only derived from the AC133+ fraction and PDGF-AA supported continued expansion of these cells. These data show that neural precursors express PDGFRα and the long-term culture of AC133+ neural precursors is supported by PDGF-AA, a specific ligand for this receptor.

When mid-gestation neural precursors were passaged in FGF-2, PDGF-AA or both growth factors, almost all the cells expressed PDGFRα and several other markers including nestin, Sox2, A2B5, NG2, and Olig2 found on immature neural precursors (Fig 1C–F, 2B) 6, 24, 40–43. Freshly isolated primary E13.5 cortical cells were mostly negative for these markers suggesting that a distinct and relatively homogeneous set of cells are supported by the growth factors (Fig 1C–F).

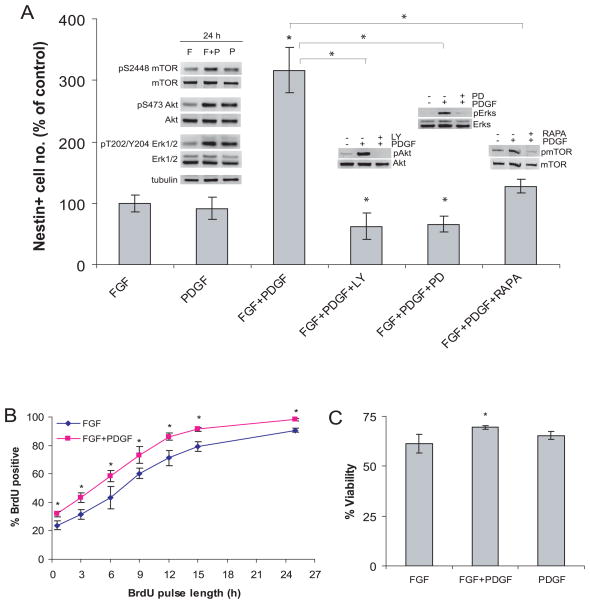

Figure 2. Co-stimulation with PDGF-AA increases nestin+ cell number, viability, and proliferation; and activates mTOR PI3K/Akt, MEK/Erk pathways.

(A) CNS stem cell-enriched cultures were plated at low density (5,000 cells/cm2) and grown for 4 d ± FGF2, PDGF-AA, inhibitors of PI3K (LY, LY294002, 10 μM), MEK (PD, PD98059, 50 μM) and mTOR (RAPA, rapamycin, 1μM). Cell number (mean ± s.d., n = 4, *p < 0.03) is expressed as percent of control (FGF2). WB analyses confirm inhibition of mTOR PI3K/Akt, MEK/Erk pathways. (B) CNS stem cell-enriched cultures treated with FGF2 alone vs. FGF2 and PDGF-AA were pulsed with 10 μM BrdU for increasing time periods, fixed, and labeled with anti-BrdU antibody (mean ± s.d., n = 3, *p < 0.015). To compare S-phase entry of control cells with cells switched from FGF2 to PDGF-AA, cells were pulsed for 24 h, and labeled with anti-BrdU antibody (mean ± s.d., n = 3 per timepoint, n.s. = non-significant). (C) CNS stem cell-enriched cultures were grown for 3 d ± FGF2, PDGF-AA, and viability was analyzed based on propidium-iodide exclusion using FACS (n = 3, *p < 0.05).

Treating these cells with PDGF-AA induced three changes that were not seen when the cells were treated with FGF2 alone: (1) At 12 h, the cells became phase-bright and bipolar. (2) PDGF-AA stimulation rapidly activated PI3K/Akt and MEK/Erk pathways. Although the tyrosine phosphorylation of PDGFRα was short-lived, the Ser473 phosphorylation on Akt and Thr202 and Tyr204 phosphorylation on Erk1/2 was sustained for 12 hours (Fig 1G). (3) In contrast to neuroepithelial cells that express high levels of Sox1 and Sox2, oligodendrocyte precursors show elevated expression of Sox1044–46. PDGF-AA increased mRNA levels of Sox10 but did not affect the level of Cnp1, a gene that is expressed at high levels later in the oligodendrocyte differentiation program (Fig 1H). This response suggests that PDGF-AA might promote the differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursors from this telencephalic source.

Ligands and signaling pathways controlling nestin+ cell number in vitro

PDGFRα stimulation is associated with oligodendrocyte precursor expansion25, 26. Although receptor tyrosine kinases, such as insulin, FGF and PDGF receptors, are known to activate similar downstream second messenger signaling pathways they also have distinct actions 47. PDGF-AA and FGF2 can interact to promote the expansion and differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursors48, 49 and both corresponding receptor-signaling pathways are known to act synergistically in other cell types50, 51. Treatment with FGF2+PDGF-AA increased the number of nestin-positive cells in FGF2-expanded CNS stem cell cultures and in primary E13.5 cortical cell cultures by two to three-fold (316 ± 18.6% and 233 ± 37.8% of FGF2-treated controls, respectively; p < 0.02; Figs 2A and 3B). The increases in cell number correlated with increased Erk1/2, Akt, and mTOR phosphorylation (at 24 h) in PDGF-AA-treated cultures versus control cultures in FGF2 alone (Fig 2A). The cell number associated with PDGF-AA treatment was suppressed by PI3K, MEK, and mTOR inhibitors, LY294002 (10 μM), PD98059 (50 μM), rapamycin (1 μM; 62.5 ± 21.1%, 65.9 ± 13.0%, 127 ± 37.2%, respectively, vs. 316 ± 18.6% FGF2+PDGF-AA, p < 0.03, Fig 2A). Western blotting confirmed inhibition of these three pathways (Fig 2A). These data show that the increased number of cells generated by combined PDGF-AA and FGF2 treatment requires activation of Akt, Erk1/2, and mTOR.

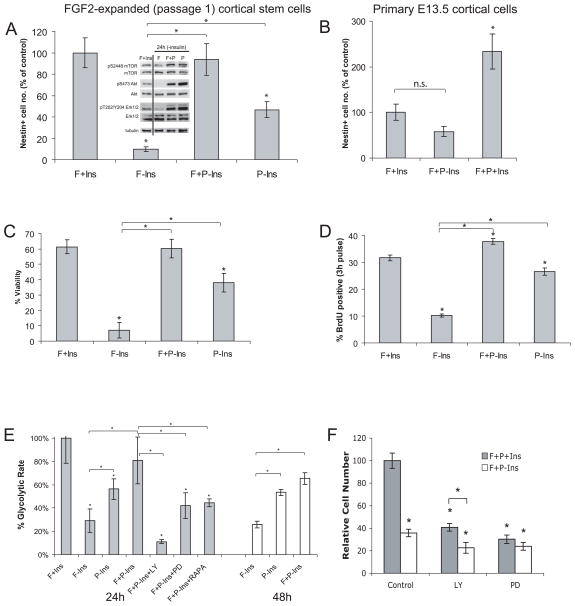

Figure 3. PDGF-AA rescues nestin+ cell number, viability, and proliferation in the absence of FGF2 and insulin and increases glycolytic rate.

(A) CNS stem cell-enriched cultures were plated at low density and grown for 4 d ± FGF2 (F), PDGF-AA (P), and insulin (Ins). Cell number (mean ± s.d., n = 4, *p < 0.001) is expressed as percent of control (FGF2). (B) Freshly dissected E13.5 primary cortical cells were plated at low density and grown for 4 d ± FGF2, PDGF-AA, and insulin (mean ± s.e.m., n.s. = non-significant [p = 0.09], *p < 0.02). (C) CNS stem cell-enriched cultures were grown for 3 d ± FGF2, PDGF-AA, and insulin; viability was analyzed based on propidium-iodide exclusion using FACS (mean ± s.d., n = 3, *p < 0.003). (D) CNS stem cell-enriched cultures were pulsed with BrdU for 3 h, fixed and then labeled with an anti-BrdU antibody (mean ± s.d., n = 3, *p < 0.003). (E) CNS stem cell-enriched cultures were cultured for 24 or 48 h ± F, P, Ins, LY, PD, or RAPA and glycolytic rate was measured. Glycolytic rate (mean ± s.d., n = 4, *p < 0.015) is expressed as percent of control (F+Ins). (F) CNS stem cell-enriched cultures were plated at low density and grown for 4 d with FGF2 and PDGF-AA and ± insulin and inhibitors of PI3K (LY, LY294002, 10 μM), MEK (PD, PD98059, 50 μM) (mean ± s.d., n = 3).

To assess whether the PDGF-AA induced increase in cell number was due to changes in proliferation, cells were pulsed with BrdU for increasing periods of time, and the proportion of cells undergoing S-phase during each pulse was analyzed by immunocytochemistry. At each pulse length, a consistent increase in BrdU incorporation was observed among PDGF-AA treated cells compared to control cells (e.g. for a 12 h pulse, 71.1 ± 4.15% for FGF2 vs. 86.2 ± 1.51% for FGF2 + PDGF-AA; p < 0.015 at all pulse lengths; Fig 2B). However, the slopes during the linear and plateau phases of the BrdU incorporation curve were similar in both groups indicating that PDGF-AA does not change cell cycle length (data not shown), but rather increases the proportion of mitotic cells. A modest but significant increase in cell viability was observed by PDGF-AA treatment, as measured by propidium iodide exclusion (61.3 ± 4.62% in controls to 69.5 ± 0.955%, p < 0.05; n = 3; Fig 2F). These data suggest that FGF2 and PDGF-AA cause an increase in cell number by regulating the proportion of cells in cycle and by a modest improvement in cell viability.

CNS stem cell-enriched cultures contain high concentrations of exogenous insulin (25 μg/ml), a growth factor that promotes cell survival and increases oligodendrocyte numbers in vitro and in vivo52, 53. In the absence of insulin, PDGF-AA restored cell number (FGF2: 9.88 ± 2.30% of control, p < 0.0002; FGF2+PDGF-AA: 93 ± 14.85%; PDGF-AA only: 46.7 ± 7.31%; Fig 3A). Similar effects on cell number were seen in primary E13.5 cortical cultures (100 ± 35.3% in FGF2+insulin vs. 58.1 ± 22.2% in FGF2+PDGF-AA minus insulin, p = 0.09; Fig 3B). These data show that PDGF-AA and insulin have an effect on cell number that is distinct from FGF2. With insulin alone, these cells exit the cycle and differentiate6. With FGF2 alone, they die (Fig 3C). PDGF-AA acts a survival factor and a mitogen (Fig 3C and D). Western blotting shows that in the absence of insulin, PDGF treatment activates Ser2448 on mTOR and Ser473 on Akt post-translational modifications associated with cell growth and survival54 (Fig 3A).

The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway regulates mitochondrial function and mitochondrial effects on cell survival55–59. Glycolysis generates pyruvate and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), both of which are required for mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation60. The conversion of [5-3H]glucose to 3H2O was used to determine whether PDGF-AA treatment regulates glycolytic rate. Twenty-four hours after insulin withdrawal, the glycolytic rate dropped (100 ± 21.4% vs. 29.3 ± 10.1%; p < 0.0001, Fig 3E). Co-stimulation with PDGF-AA abrogated this decrease (FGF2+insulin: 100 ± 21.4% vs. FGF2+PDGF-AA minus insulin 80.9 ± 20.3%; p = 0.105, Fig 3E). Switching to PDGF-AA alone showed much higher glycolytic rate than culture in FGF2 alone (56.3 ± 8.81%; p < 0.01, Fig 3E). Forty-eight hours after insulin withdrawal, the same pattern remained showing that PDGF-AA stimulates the glycolytic rate.

Pretreatment with either the MEK inhibitor PD98059 or the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin nearly halved the glycolytic rate but the PI3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 further reduced the glycolytic rate (FGF2+PDGF-AA minus insulin: 80.9 ± 20.3%; FGF2+PDGF-AA+rapamycin minus insulin 44.4 ± 3.25%; FGF2+PDGF-AA+PD98059 minus insulin 42.2 ± 10.8%; FGF2+PDGF-AA+LY294002 minus insulin 11.2 ± 3.25%. FGF2+PDGF-AA minus insulin vs. each inhibitor-treated group, p < 0.015, Fig 3E). These data suggest that PI3K/Akt, mTOR and MEK/Erk all contribute to the glycolytic rate in PDGF-AA treated cells.

The pattern of cell viability, cell number and glycolytic rate suggest that PDGF-AA can partially substitute for insulin. However, an increased cell number was seen when the primary E13.5 cells were treated with all three growth factors (Fig. 3B). The same is true for cells expanded in vitro, where insulin contributes to cell number and both the PI3K/Akt and MEK/Erk pathways are required (Fig. 3F). These data show that PDGF-AA interacts at a fundamental level with FGF2 and insulin to maintain nestin+ precursors in vitro.

PDGF-AA promotes oligodendrocyte-lineage differentiation

PDFGRα is expressed in oligodendrocyte precursors in the developing brain and in multipotent precursors in the adult CNS24, 36. In vivo, it is difficult to determine if a multipotent precursor can rapidly generate glial progenitors. The in vitro results presented here show that a significant increase in cell number is achieved by PDGF-AA, suggesting that large numbers of oligodendrocyte precursors may be present in the treated population. PDGF-AA treatment of CNS stem cell-enriched cultures also resulted in a rapid morphological change generating bipolar cells similar to the O2-A oligodendrocyte precursor derived from the optic nerve28, 61, 62 (Fig 1C). This rapid morphological change (generally first seen within 12 h) suggests that a brief treatment of PDGF-AA may be sufficient to trigger an increase in the numbers of oligodendrocyte precursors.

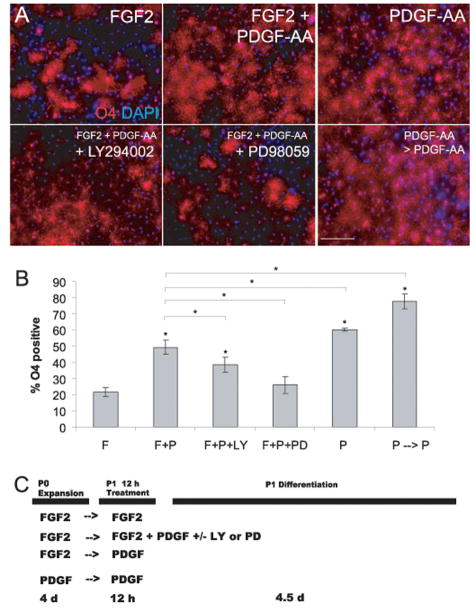

Cells at passage 0 were grown in FGF2, passaged, and then treated with different factors for the first 12 hours, followed by culture in differentiation conditions (Neurobasal + B27 supplement without PDGF-AA or FGF2) for 4.5 d (Fig 4A–C). By 3–4 d, obvious morphological signs of oligodendroglial precursors were present in all conditions. At 4–5 d, immunocytochemistry with the lineage-specific antibody, O4, confirmed the presence of oligodendrocyte-lineage cells in all conditions. This short exposure to PDGF-AA increased the proportion of post-mitotic O4+ oligodendrocyte-lineage cells by 2.3 and 2.8 fold, respectively (FGF2-only control: 21.4 ± 2.81%; FGF2+PDGF-AA: 49.3 ± 4.25%; PDGF-AA: 60.3 ± 0.918%. Control vs. each PDGF-AA treated group, p < 0.00003; Fig 4A and B, see Fig 5B for BrdU incorporation at 4.5 d). A high proportion of oligodendrocyte precursors could also be derived when primary fetal cortical cells were placed directly into PDGF-AA (without exogenous FGF2) and maintained in this growth factor throughout passage (PDGF-AA only/P → P: 77.4 ± 4.67%; Fig 4A and B, Fig 5B). Transient blockade of the PI3K/Akt pathway decreased the proportion of oligodendrocytes following PDGF-AA treatment, while inhibition of the MEK/Erk pathway reduced this proportion even further (FGF2+PDGF-AA+LY294002: 38.5 ± 4.71% [vs. FGF2 only, p < 0.002; vs. FGF2+PDGF-AA, p < 0.025]; FGF2+PDGF-AA+PD98059: 26.0 ± 5.38% [vs. FGF2 only, p = 0.200; vs. FGF2+PDGF-AA, p < 0.0015]; Fig 4A and B). These data show that the MEK/Erk pathway is required for the oligodendrogliogenesis observed in PDGF-AA treated cells.

Figure 4. PDGF-AA promotes oligodendrogliogenesis from CNS stem cell-enriched cultures.

(A) CNS stem cells were plated at 25,000 cells/cm2 and pulsed for 12 h ± FGF2, PDGF-AA, LY, and/or PD (cultures were pretreated with inhibitors for 1 h prior to PDGF-AA pulse). Cells in “PDGF-AA only” group were obtained by plating primary E13.5 cortical cells in PDGF-AA alone (no exogeneous FGF2 was added) for 5–7 d, passaging, and plating at same density as FGF2-expanded CNS stem cells. This enriched population of oligodendrocyte precursors was treated with PDGF-AA for an additional 12 h. After cytokine and/or inhibitor treatment, cells were then switched to serum-free differentiation medium, cultured for 4–5 d, fixed, and labeled with anti-O4 antibody. Scale bar = 20 μm. (B) Percentage of O4+ oligodendrocytes of total cells (mean ± s.d., n = 4 [n = 3 for inhibitor-treated groups], *p < 0.025). (C) Treatment scheme used in (A) and (B)

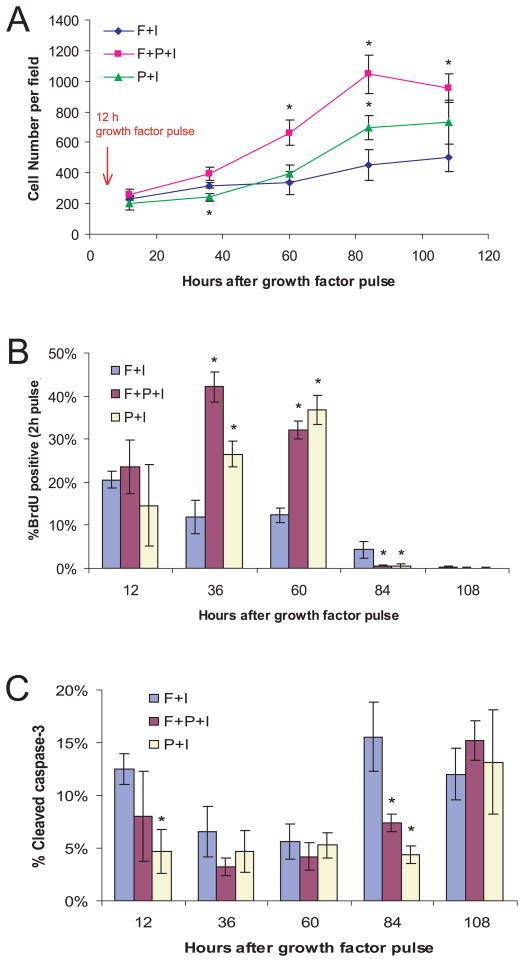

Figure 5. Transient exposure to PDGF-AA is associated with a delay in cell cycle exit during differentiation.

(A) CNS stem cells were treated as in Fig 4A. Twelve, 36, 60, 84, and 108 hours after growth factor pulse, differentiating cells were fixed (BrdU was added 2 h before fixation as indicated), and cell number, (B) S-phase, and (C) apoptosis was measured by labeling with DAPI, anti-BrdU, and anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibodies (mean ± s.d., n = 3 for each timepoint, *p < 0.04).

This short pulse affected not only oligodendrogliogenesis but also the total cell number over the following four days (Fig 5A). Cultures co-stimulated with a 12 h pulse of PDGF-AA+FGF2 showed a clear increase in total cell number. In contrast, in cultures treated for 12 hours with either PDGF-AA or FGF2 showed a smaller increase in cell number (FGF2-only control: 499 ± 92.4 cells/field, FGF2+PDGF-AA: 956 ± 92.3, p < 0.005; PDGF-AA: 732 ± 143, p = 0.0826; Fig 5A). To directly monitor proliferation during this period, parallel cultures were exposed to BrdU 2 h before fixation, every day for 4 d, and stained with an anti-BrdU antibody to score cells undergoing S-phase (Fig 5 B). Apoptosis was measured with an antibody against caspase-3 (Fig 5C). Twenty-four to 48 h after withdrawal of PDGF-AA, treated cells exhibited a 2.23 to 3.55-fold increase in BrdU incorporation and apoptosis was transiently suppressed (e.g. BrdU+ at 24 h, FGF2-only control: 11.8 ± 3.87%, FGF2+PDGF-AA: 42.1 ± 3.60%, p < 0.00075; FGF2→PDGF-AA: 26.5 ± 2.98%, p < 0.0075; Fig 5B and C). These data show that a brief exposure to PDGF-AA stimulates a wave of proliferation of oligodendrocyte precursors.

Discussion

Clonal analysis shows that multipotent cells can be isolated from the CNS that give rise to neurons and glia6. The proportion of differentiated cells can be regulated by single factors and the differentiation to astrocytes by activation of the Jak/STAT pathway has been widely studied as a model of fate choice 7, 8, 63–65. A simple method to generate oligodendrocytes from CNS stem cell-enriched cultures might also contribute to our understanding differentiation pathways. Here we show that PDGF-AA, through PDGFRα, leads to a rapid increase in the proportion of oligodendrocyte precursors. The growth factor stimulates rapid and long-lasting activation of Akt and Erk1/2 66 but phosphorylation of Tyr705 on STAT3 was not observed (data not shown). The use of pharmacological inhibitors suggests that both Akt and Erk activation are required for oligodendrocyte differentiation.

We have previously reported that continuous PDGF-AA treatment of rat embryonic and adult CNS stem cells promotes continued proliferation of a neuronal-type precursor, based on expression of the antigen, MAP26. However, there are also reports of MAP2 expression in the oligodendrocyte lineage67, 68. Here we used another chemically-defined medium, Neurobasal plus B-27 supplement, to promote survival. Here we report that extensive oligodendroglial differentiation occurs in response to a pulse of PDGF-AA in this medium. In vivo studies show that PDGF-AA stimulates expansion of CNS stem cells that differentiate into oligodendrocytes 24. The in vitro system we report can now be used to analyze in more detail how PDGF-AA responses including glucose metabolism, growth and survival signaling lead to oligodendrocyte-lineage specification.

We report here that PDGFRα is expressed in fetal neural stem cells in vitro. Recently, PDGFRα+ subventricular zone (SVZ) astrocytes were identified as a subset of adult neural stem cells particularly sensitive to increased PDGFRα signaling 24. Continuous infusion of PDGF-AA induced the formation of large hyperplasias with some features of glioma. Indeed, autocrine PDGF signaling—most commonly overexpression of the ligand and/or receptor—is found in most human gliomas69. In contrast, mutations or overexpression in FGF or insulin signaling are less frequently associated with glioma70. Moreover, AC133 has recently been shown to identify “tumor-initiating stem cells,” a rare subset of cells required for tumor growth, in human glioma, colon, and other cancers 71–73. Our findings that AC133 selection enriches for PDGF-responsive cells from embryonic cortex, and that PDGF-AA activates PI3K/Akt, MEK/Erk, and mTOR pathways in cultured CNS stem cells to a greater degree than does FGF2 and insulin may explain why aberrant PDGF signaling is so frequently found in gliomas. Furthermore, our data raise the possibility that AC133+ glioma stem cells, similar to the AC133+ fetal CNS progenitors we isolate here, may be particularly responsive to increased PDGF signaling.

The initial isolation of oligodendrocyte precursors involved extensive, multi-step purification, serum-containing procedures (e.g. immunopanning, complement lysis, differential adhesion, use of B104 neuroblastoma conditioned media and fetal bovine serum) from postnatal tissues of the forebrain and optic nerve74–76. Subsequent studies derived oligodendrocytes from stem cells by differential growth conditions, genetic engineering or prolonged exposure to neuroblastoma-conditioned media that promote expansion of oligodendrocyte precursors 11, 77–81. Although these methods generate cell populations that are enriched for oligodendrocyte precursors, the step when oligodendrocyte-lineage cells are first established has not been defined. Here we identify serum-free conditions that rapidly generate oligodendrocyte precursors from CNS stem cell-enriched cultures or from primary mid-gestation cortical cells. These cells continue to divide and can be passaged up to 4–5 times without exogenous FGF2 or insulin, enabling the generation of tens of millions of oligodendrocyte precursors from a single embryo. Withdrawal of PDGF-AA induced cell cycle exit, morphologic maturation and increased expression of the O4 antigen characteristic of oligodendrocyte-lineage cells in 60–80% of the cells. The conclusion from this report is that oligodendrocyte precursors can be efficiently generated from CNS stem cell-enriched cultures. In the future, it will be interesting ask if this effect is mediated by instructive or selective mechanisms and if human oligodendrocyte precursors can be derived by a similar strategy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jeanette Beers and Ramesh Potla for assistance with FACS analysis and glycolytic rate assays. We would like to acknowledge Sachiko Murase for critical discussion of the manuscript. We also thank Andreas Theotokis-Androutsellis, Andrei Kuzmichev, Dan Hoeppner, Rea Ravin and Steven Poser for their advice and suggestions to optimize cell culture and other assays. We are grateful to Hirohide Takebayashi (National Institute for Physiological Sciences, Okazaki, Japan) for his gift of Olig2 antibody. This work was supported by the Intramural Program of the National Institutes of Health—National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NIH-NINDS). R.C.R. was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute-NIH Research Scholars Program and a T35 HL07649 NIH Research Award through Yale University School of Medicine.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

Author contributions:

Rajesh C. Rao: Conception and design, collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing

Justin Boyd: collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation

Raji Padmanabhan: collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation

Josh G. Chenoweth: collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation

R.D. McKay: Conception and design, financial support, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript

References

- 1.McKay R. Stem cells in the central nervous system. Science. 1997 Apr 4;276(5309):66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gage FH. Mammalian neural stem cells. Science. 2000 Feb 25;287(5457):1433–1438. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uchida N, Buck DW, He D, et al. Direct isolation of human central nervous system stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000 Dec 19;97(26):14720–14725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okabe S, Forsberg-Nilsson K, Spiro AC, Segal M, McKay RD. Development of neuronal precursor cells and functional postmitotic neurons from embryonic stem cells in vitro. Mech Dev. 1996 Sep;59(1):89–102. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(96)00572-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang SC, Wernig M, Duncan ID, Brustle O, Thomson JA. In vitro differentiation of transplantable neural precursors from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2001 Dec;19(12):1129–1133. doi: 10.1038/nbt1201-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johe KK, Hazel TG, Muller T, Dugich-Djordjevic MM, McKay RD. Single factors direct the differentiation of stem cells from the fetal and adult central nervous system. Genes Dev. 1996 Dec 15;10(24):3129–3140. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.24.3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonni A, Sun Y, Nadal-Vicens M, et al. Regulation of gliogenesis in the central nervous system by the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Science. 1997 Oct 17;278(5337):477–483. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajan P, Panchision DM, Newell LF, McKay RD. BMPs signal alternately through a SMAD or FRAP-STAT pathway to regulate fate choice in CNS stem cells. J Cell Biol. 2003 Jun 9;161(5):911–921. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He F, Ge W, Martinowich K, et al. A positive autoregulatory loop of Jak-STAT signaling controls the onset of astrogliogenesis. Nat Neurosci. 2005 May;8(5):616–625. doi: 10.1038/nn1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnabe-Heider F, Wasylnka JA, Fernandes KJ, et al. Evidence that embryonic neurons regulate the onset of cortical gliogenesis via cardiotrophin-1. Neuron. 2005 Oct 20;48(2):253–265. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brustle O, Jones KN, Learish RD, et al. Embryonic stem cell-derived glial precursors: a source of myelinating transplants. Science. 1999 Jul 30;285(5428):754–756. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keirstead HS, Nistor G, Bernal G, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived oligodendrocyte progenitor cell transplants remyelinate and restore locomotion after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2005 May 11;25(19):4694–4705. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0311-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keirstead HS. Stem cells for the treatment of myelin loss. Trends Neurosci. 2005 Dec;28(12):677–683. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heldin CH, Westermark B, Wasteson A. Platelet-derived growth factor: purification and partial characterization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979 Aug;76(8):3722–3726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.8.3722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doolittle RF, Hunkapiller MW, Hood LE, et al. Simian sarcoma virus onc gene, v-sis, is derived from the gene (or genes) encoding a platelet-derived growth factor. Science. 1983 Jul 15;221(4607):275–277. doi: 10.1126/science.6304883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waterfield MD, Scrace GT, Whittle N, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor is structurally related to the putative transforming protein p28sis of simian sarcoma virus. Nature. 1983 Jul 7–13;304(5921):35–39. doi: 10.1038/304035a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franke TF, Yang SI, Chan TO, et al. The protein kinase encoded by the Akt proto-oncogene is a target of the PDGF-activated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Cell. 1995 Jun 2;81(5):727–736. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Auger KR, Serunian LA, Soltoff SP, Libby P, Cantley LC. PDGF-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation stimulates production of novel polyphosphoinositides in intact cells. Cell. 1989 Apr 7;57(1):167–175. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90182-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marrero MB, Schieffer B, Li B, Sun J, Harp JB, Ling BN. Role of Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription and mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in angiotensin II- and platelet-derived growth factor-induced vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 1997 Sep 26;272(39):24684–24690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoch RV, Soriano P. Roles of PDGF in animal development. Development. 2003 Oct;130(20):4769–4784. doi: 10.1242/dev.00721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fruttiger M, Calver AR, Kruger WH, et al. PDGF mediates a neuron-astrocyte interaction in the developing retina. Neuron. 1996 Dec;17(6):1117–1131. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80244-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oumesmar BN, Vignais L, Baron-Van Evercooren A. Developmental expression of platelet-derived growth factor alpha-receptor in neurons and glial cells of the mouse CNS. J Neurosci. 1997 Jan 1;17(1):125–139. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00125.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrae J, Hansson I, Afink GB, Nister M. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha in ventricular zone cells and in developing neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2001 Jun;17(6):1001–1013. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.0989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson EL, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Gil-Perotin S, et al. PDGFR alpha-positive B cells are neural stem cells in the adult SVZ that form glioma-like growths in response to increased PDGF signaling. Neuron. 2006 Jul 20;51(2):187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calver AR, Hall AC, Yu WP, et al. Oligodendrocyte population dynamics and the role of PDGF in vivo. Neuron. 1998 May;20(5):869–882. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80469-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pringle N, Collarini EJ, Mosley MJ, Heldin CH, Westermark B, Richardson WD. PDGF A chain homodimers drive proliferation of bipotential (O-2A) glial progenitor cells in the developing rat optic nerve. Embo J. 1989 Apr;8(4):1049–1056. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03472.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raff MC, Lillien LE, Richardson WD, Burne JF, Noble MD. Platelet-derived growth factor from astrocytes drives the clock that times oligodendrocyte development in culture. Nature. 1988 Jun 9;333(6173):562–565. doi: 10.1038/333562a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noble M, Murray K, Stroobant P, Waterfield MD, Riddle P. Platelet-derived growth factor promotes division and motility and inhibits premature differentiation of the oligodendrocyte/type-2 astrocyte progenitor cell. Nature. 1988 Jun 9;333(6173):560–562. doi: 10.1038/333560a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raff MC, Lillien LE. Differentiation of a bipotential glial progenitor cell: what controls the timing and the choice of developmental pathway? J Cell Sci Suppl. 1988;10:77–83. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1988.supplement_10.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hinks GL, Franklin RJ. Distinctive patterns of PDGF-A, FGF-2, IGF-I, and TGF-beta1 gene expression during remyelination of experimentally-induced spinal cord demyelination. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999 Aug;14(2):153–168. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vana AC, Flint NC, Harwood NE, Le TQ, Fruttiger M, Armstrong RC. Platelet-derived growth factor promotes repair of chronically demyelinated white matter. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007 Nov;66(11):975–988. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181587d46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat Biotechnol. 2008 Jan;26(1):101–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Androutsellis-Theotokis A, Leker RR, Soldner F, et al. Notch signalling regulates stem cell numbers in vitro and in vivo. Nature. 2006 Aug 17;442(7104):823–826. doi: 10.1038/nature04940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sailer MH, Hazel TG, Panchision DM, Hoeppner DJ, Schwab ME, McKay RD. BMP2 and FGF2 cooperate to induce neural-crest-like fates from fetal and adult CNS stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2005 Dec 15;118(Pt 24):5849–5860. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edinger AL, Thompson CB. An activated mTOR mutant supports growth factor-independent, nutrient-dependent cell survival. Oncogene. 2004 Jul 22;23(33):5654–5663. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pringle NP, Mudhar HS, Collarini EJ, Richardson WD. PDGF receptors in the rat CNS: during late neurogenesis, PDGF alpha-receptor expression appears to be restricted to glial cells of the oligodendrocyte lineage. Development. 1992 Jun;115(2):535–551. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.2.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee A, Kessler JD, Read TA, et al. Isolation of neural stem cells from the postnatal cerebellum. Nat Neurosci. 2005 Jun;8(6):723–729. doi: 10.1038/nn1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yin AH, Miraglia S, Zanjani ED, et al. AC133, a novel marker for human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood. 1997 Dec 15;90(12):5002–5012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Padmanabhan R, Padmanabhan R, Howard T, Gottesman MM, Howard BH. Magnetic affinity cell sorting to isolate transiently transfected cells, multidrug-resistant cells, somatic cell hybrids, and virally infected cells. Methods Enzymol. 1993;218:637–651. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)18047-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ida M, Shuo T, Hirano K, et al. Identification and functions of chondroitin sulfate in the milieu of neural stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2006 Mar 3;281(9):5982–5991. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507130200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ligon KL, Huillard E, Mehta S, et al. Olig2-regulated lineage-restricted pathway controls replication competence in neural stem cells and malignant glioma. Neuron. 2007 Feb 15;53(4):503–517. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miyagi S, Nishimoto M, Saito T, et al. The Sox2 regulatory region 2 functions as a neural stem cell-specific enhancer in the telencephalon. J Biol Chem. 2006 May 12;281(19):13374–13381. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512669200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nunes MC, Roy NS, Keyoung HM, et al. Identification and isolation of multipotential neural progenitor cells from the subcortical white matter of the adult human brain. Nat Med. 2003 Apr;9(4):439–447. doi: 10.1038/nm837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuhlbrodt K, Herbarth B, Sock E, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Wegner M. Sox10, a novel transcriptional modulator in glial cells. J Neurosci. 1998 Jan 1;18(1):237–250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00237.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kessaris N, Fogarty M, Iannarelli P, Grist M, Wegner M, Richardson WD. Competing waves of oligodendrocytes in the forebrain and postnatal elimination of an embryonic lineage. Nat Neurosci. 2006 Feb;9(2):173–179. doi: 10.1038/nn1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lappe-Siefke C, Goebbels S, Gravel M, et al. Disruption of Cnp1 uncouples oligodendroglial functions in axonal support and myelination. Nat Genet. 2003 Mar;33(3):366–374. doi: 10.1038/ng1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schlessinger J. Common and distinct elements in cellular signaling via EGF and FGF receptors. Science. 2004 Nov 26;306(5701):1506–1507. doi: 10.1126/science.1105396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolswijk G, Noble M. Cooperation between PDGF and FGF converts slowly dividing O-2Aadult progenitor cells to rapidly dividing cells with characteristics of O-2Aperinatal progenitor cells. J Cell Biol. 1992 Aug;118(4):889–900. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.4.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murtie JC, Zhou YX, Le TQ, Vana AC, Armstrong RC. PDGF and FGF2 pathways regulate distinct oligodendrocyte lineage responses in experimental demyelination with spontaneous remyelination. Neurobiol Dis. 2005 Jun-Jul;19(1–2):171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Millette E, Rauch BH, Defawe O, Kenagy RD, Daum G, Clowes AW. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB-induced human smooth muscle cell proliferation depends on basic FGF release and FGFR-1 activation. Circ Res. 2005 Feb 4;96(2):172–179. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000154595.87608.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Millette E, Rauch BH, Kenagy RD, Daum G, Clowes AW. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB transactivates the fibroblast growth factor receptor to induce proliferation in human smooth muscle cells. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2006 Jan;16(1):25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aberg ND, Johansson UE, Aberg MA, et al. Peripheral infusion of insulin-like growth factor-I increases the number of newborn oligodendrocytes in the cerebral cortex of adult hypophysectomized rats. Endocrinology. 2007 Aug;148(8):3765–3772. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zeger M, Popken G, Zhang J, et al. Insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor signaling in the cells of oligodendrocyte lineage is required for normal in vivo oligodendrocyte development and myelination. Glia. 2007 Mar;55(4):400–411. doi: 10.1002/glia.20469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bhaskar PT, Hay N. The two TORCs and Akt. Dev Cell. 2007 Apr;12(4):487–502. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wieman HL, Wofford JA, Rathmell JC. Cytokine stimulation promotes glucose uptake via phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/Akt regulation of Glut1 activity and trafficking. Mol Biol Cell. 2007 Apr;18(4):1437–1446. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-07-0593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rathmell JC, Fox CJ, Plas DR, Hammerman PS, Cinalli RM, Thompson CB. Akt-directed glucose metabolism can prevent Bax conformation change and promote growth factor-independent survival. Mol Cell Biol. 2003 Oct;23(20):7315–7328. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7315-7328.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schieke SM, Phillips D, McCoy JP, Jr, et al. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway regulates mitochondrial oxygen consumption and oxidative capacity. J Biol Chem. 2006 Sep 15;281(37):27643–27652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu X, Reiter CE, Antonetti DA, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS, Gardner TW. Insulin promotes rat retinal neuronal cell survival in a p70S6K-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2004 Mar 5;279(10):9167–9175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312397200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cunningham JT, Rodgers JT, Arlow DH, Vazquez F, Mootha VK, Puigserver P. mTOR controls mitochondrial oxidative function through a YY1-PGC-1alpha transcriptional complex. Nature. 2007 Nov 29;450(7170):736–740. doi: 10.1038/nature06322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin SJ, Kaeberlein M, Andalis AA, et al. Calorie restriction extends Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan by increasing respiration. Nature. 2002 Jul 18;418(6895):344–348. doi: 10.1038/nature00829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Noble M, Murray K. Purified astrocytes promote the in vitro division of a bipotential glial progenitor cell. Embo J. 1984 Oct;3(10):2243–2247. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Temple S, Raff MC. Differentiation of a bipotential glial progenitor cell in a single cell microculture. Nature. 1985 Jan 17–23;313(5999):223–225. doi: 10.1038/313223a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rajan P, McKay RD. Multiple routes to astrocytic differentiation in the CNS. J Neurosci. 1998 May 15;18(10):3620–3629. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03620.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hermanson O, Jepsen K, Rosenfeld MG. N-CoR controls differentiation of neural stem cells into astrocytes. Nature. 2002 Oct 31;419(6910):934–939. doi: 10.1038/nature01156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Song MR, Ghosh A. FGF2-induced chromatin remodeling regulates CNTF-mediated gene expression and astrocyte differentiation. Nat Neurosci. 2004 Mar;7(3):229–235. doi: 10.1038/nn1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shin SY, Bahk YY, Ko J, et al. Suppression of Egr-1 transcription through targeting of the serum response factor by oncogenic H-Ras. Embo J. 2006 Mar 8;25(5):1093–1103. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Muller R, Heinrich M, Heck S, Blohm D, Richter-Landsberg C. Expression of microtubule-associated proteins MAP2 and tau in cultured rat brain oligodendrocytes. Cell Tissue Res. 1997 May;288(2):239–249. doi: 10.1007/s004410050809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Richter-Landsberg C, Gorath M. Developmental regulation of alternatively spliced isoforms of mRNA encoding MAP2 and tau in rat brain oligodendrocytes during culture maturation. J Neurosci Res. 1999 May 1;56(3):259–270. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990501)56:3<259::AID-JNR5>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lokker NA, Sullivan CM, Hollenbach SJ, Israel MA, Giese NA. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) autocrine signaling regulates survival and mitogenic pathways in glioblastoma cells: evidence that the novel PDGF-C and PDGF-D ligands may play a role in the development of brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2002 Jul 1;62(13):3729–3735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pollack IF, Randall MS, Kristofik MP, Kelly RH, Selker RG, Vertosick FT., Jr Response of low-passage human malignant gliomas in vitro to stimulation and selective inhibition of growth factor-mediated pathways. J Neurosurg. 1991 Aug;75(2):284–293. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.2.0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004 Nov 18;432(7015):396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, et al. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature. 2007 Jan 4;445(7123):111–115. doi: 10.1038/nature05384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li Y, Koeneman KS. Prostate cancer cells with stem cell characteristics reconstitute the original human tumor in vivo Gu G, Yuan J, Wills M, Kasper S, Department of Urologic Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center; Department of Pathology, Vanderbilt Children’s Hospital; The Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, Nashville, TN. Urol Oncol. 2008 Jan-Feb;26(1):112. [Google Scholar]

- 74.McCarthy KD, de Vellis J. Preparation of separate astroglial and oligodendroglial cell cultures from rat cerebral tissue. J Cell Biol. 1980 Jun;85(3):890–902. doi: 10.1083/jcb.85.3.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Barres BA, Hart IK, Coles HS, et al. Cell death in the oligodendrocyte lineage. J Neurobiol. 1992 Nov;23(9):1221–1230. doi: 10.1002/neu.480230912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Raff MC, Miller RH, Noble M. A glial progenitor cell that develops in vitro into an astrocyte or an oligodendrocyte depending on culture medium. Nature. 1983 Jun 2–8;303(5916):390–396. doi: 10.1038/303390a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nistor GI, Totoiu MO, Haque N, Carpenter MK, Keirstead HS. Human embryonic stem cells differentiate into oligodendrocytes in high purity and myelinate after spinal cord transplantation. Glia. 2005 Feb;49(3):385–396. doi: 10.1002/glia.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Avellana-Adalid V, Nait-Oumesmar B, Lachapelle F, Baron-Van Evercooren A. Expansion of rat oligodendrocyte progenitors into proliferative “oligospheres” that retain differentiation potential. J Neurosci Res. 1996 Sep 1;45(5):558–570. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960901)45:5<558::AID-JNR6>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang SC, Lundberg C, Lipsitz D, O’Connor LT, Duncan ID. Generation of oligodendroglial progenitors from neural stem cells. J Neurocytol. 1998;27(7):475–489. doi: 10.1023/a:1006953023845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Billon N, Jolicoeur C, Ying QL, Smith A, Raff M. Normal timing of oligodendrocyte development from genetically engineered, lineage-selectable mouse ES cells. J Cell Sci. 2002 Sep 15;115(Pt 18):3657–3665. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Glaser T, Perez-Bouza A, Klein K, Brustle O. Generation of purified oligodendrocyte progenitors from embryonic stem cells. Faseb J. 2005 Jan;19(1):112–114. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1931fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]