Abstract

Objective

To describe the design and methodology of the Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial: Attention and Reading Trial (CITT-ART), the first randomized clinical trial evaluating the effect of vision therapy on reading and attention in school-age children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency (CI).

Methods

CITT-ART is a multicenter, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of 324 children ages 9 to 14 years in grades 3 to 8 with symptomatic CI. Participants are randomized to 16 weeks of office-based vergence/accommodative therapy (OBVAT) or placebo therapy (OBPT), both supplemented with home therapy. The primary outcome measure is the change in the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test-Version 3 (WIAT-III) reading comprehension subtest score. Secondary outcome measures are changes in attention as measured by the Strengths and Weaknesses of Attention (SWAN) as reported by parents and teachers, tests of binocular visual function, and other measures of reading and attention. The long-term effects of treatment are assessed 1 year after treatment completion. All analyses will test the null hypothesis of no difference in outcomes between the two treatment groups.

The study is entering its second year of recruitment. The final results will contribute to a better understanding of the relationship between the treatment of symptomatic CI and its effect on reading and attention.

Conclusion

The study will provide an evidence base to help parents, eye professionals, educators, and other health care providers make informed decisions as they care for children with CI and reading and attention problems. Results may also generate additional hypothesis and guide the development of other scientific investigations of the relationships between visual disorders and other developmental disorders in children.

Keywords: attention, CI, CISS, CITT, convergence insufficiency, Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey, Near point of convergence, reading, vision therapy

INTRODUCTION

Convergence insufficiency (CI) is a common binocular vision disorder, affecting approximately 5% of school-aged children.1,2 In addition to visual discomfort, children with CI report symptoms affecting reading performance, such as loss of place, loss of concentration, reading slowly, and trouble remembering what was read.3–6 Parents of children with CI report a high frequency of adverse academic behaviors (e.g., inattention, avoidance, difficulty completing homework).7 Several of the symptoms and behaviors associated with CI overlap with those reported in children diagnosed as having Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).8–10

Recent studies have established that office-based vergence/accommodative therapy (OBVAT) is an effective treatment for symptomatic CI in children.6,11,12 Successful treatment results in significantly fewer symptoms when reading6 and a lessening of problem behaviors associated with reading and school work have been reported by parents.13 While either of these scenarios could potentially lead to improvements in reading performance, few studies have specifically investigated the relationship of reading and CI in children. Improvements in reading comprehension,14 reading speed,15 and reading errors15 have been reported in school-aged children with poor convergence after treatment with office-based orthoptics14 and computerized home therapy;15 however, both studies had methodological limitations (e.g., no placebo control group, unmasked examiners, small sample size) that prevent definitive conclusions.

CI has been identified as a possible comorbid factor in ADHD. In a study of 1,700 ADHD children who had undergone eye examinations, 16% were found to have CI compared to 5–10% of children without ADHD.10 Two other uncontrolled studies have reported that children with CI score higher on the Conners Parent Rating Scale, a measure of inattention commonly used for the evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment response of children with ADHD.8,16 Furthermore, significant improvements in attention scores have been found in children after treatment of their CI.16,17

The aforementioned studies suggest that children with symptomatic CI are more likely to have attention problems during reading tasks and that the successful treatment of symptomatic CI can lead to improved attention during reading. Thus, the Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial - Attention & Reading Trial (CITT-ART) was designed as a prospective randomized trial to determine whether reading and attention improve in school-aged children with symptomatic CI who are treated with OBVAT. The purpose of this paper is to describe the study design and procedures used in the CITT-ART study.

METHODS

The study is supported through cooperative agreement grants with the National Eye Institute (NEI) of the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services and is being conducted according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki at 8 clinical sites. The protocol and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant informed consent and assent documents were approved by the respective institutional review boards (IRB). All participants provide written assent and a parent or guardian of each study participant provides written informed consent. Study oversight is provided by a NEI-appointed independent data and safety monitoring committee (DSMC) (Appendix) who approved all aspects of the study protocol, including the statistical analysis plan, prior to implementation. The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov as the Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial-ART (CITT-ART: NCT02207517).

Study Design

CITT-ART is a multicenter, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Enrollment began in August 2015 and will end in March 2017. Participants age 9 to14 years in grades 3 to 8 are randomized to: 1) office-based vergence/accommodative therapy with home reinforcement (OBVAT) or 2) office-based placebo therapy with home reinforcement (OBPT) in a 2:1 ratio. Participants in both treatment groups receive 16 weeks of treatment and interim assessments are conducted after 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks of therapy. Long-term follow up is assessed 1 year after treatment completion.

Aims

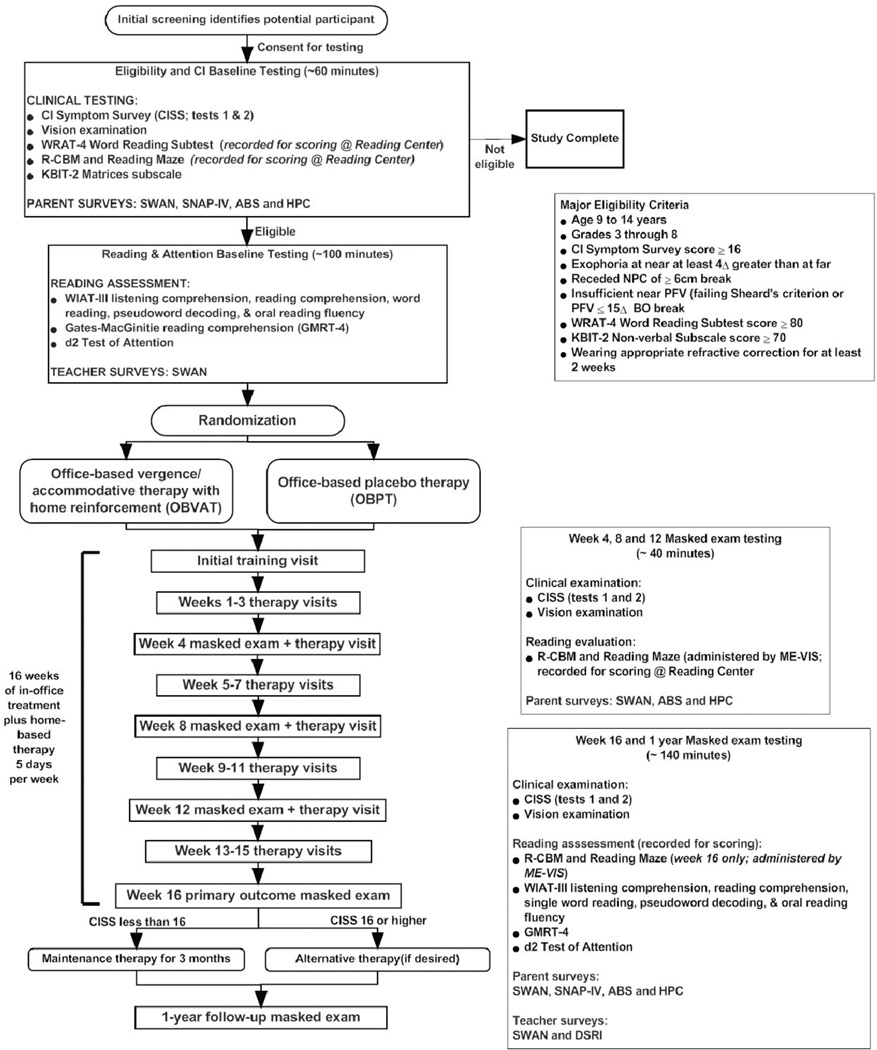

A flow chart of the study is illustrated in Figure 1. The principal aim of the study is to determine whether the treatment of childhood CI with OBVAT improves reading comprehension as measured by Wechsler Individual Achievement Test (WIAT-III). Additional reading-targeted aims are to determine if there are changes in word reading, pseudoword decoding, oral reading fluency, and listening comprehension on the WIAT-III, as well as changes in reading comprehension on the Gates-MacGinitie Reading Test (GMRT-4) and on Curriculum-based Measurements (R-CBM and Reading Maze). A secondary aim of the study is to determine if attention, as measured by the Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD Symptoms and Normal Behavior Scale (SWAN), improves after OBVAT treatment. Attention is also assessed using the parent-rated Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham-IV (SNAP-IV) scale and the d2 Test of Attention (d2).

Figure 1.

Flow Chart of the Study

We will determine the effects of treatment on symptoms using the Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey (CISS) and on clinical vergence measures [near point of convergence (NPC) and positive fusional vergence at near (PFV)]. Finally, we will determine whether any changes in reading and attention correlate with changes in symptoms and clinical measures of convergence.

Selection of Reading Outcome Measures

The reading tests that comprise the CITT-ART reading test battery were chosen because the tests 1) measure the key reading domains of word identification, fluency, and comprehension, 2) have acceptable reliability and validity, and 3) are feasible to administer in a clinical setting. The primary reading outcome measure, the Reading Comprehension subtest of the WIAT-III, was selected based on a pilot study in which we found significant improvements in test scores after OBVAT.18 The GMRT-4 was selected as a second measure of reading comprehension. Word reading and reading fluency measures are included because of the strong contributions of these domains to reading comprehension.19 Accurate and fluent word reading and linguistic comprehension contribute independently to reading comprehension,20,21 and therefore we include measures of these domains as well. The CBM measures were chosen to track changes in general reading proficiency accounting for the child's initial reading level and the time of school year.

Selection of Attention Measures

The most common assessment tool for attentional impairment is to use behavior rating scales like the SNAP, the Conners 3, or the ADHD Rating Scale, all of which are comparable in content [using symptoms listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV or DSM-5)]22 and 4-point rating intervals. A potential problem with 4-point rating scales, however, is that they collapse the average and better-functioning end of the normal distribution into a rating of 0, thus losing considerable variance for average and superior-functioning children. With ratings near 0 at baseline, any improvement from average to superior after treatment cannot be reflected using a truncated 4-point scale. Therefore, we selected the SWAN (Table 2) as our primary measure of attention, because it allows rating the full spectrum of attentional function, from ‘far above’ to ‘far below’ average on a 7-point rating scale. In this way, regardless of the distribution at baseline, the majority of children will have the opportunity to show improvement. We also included the SNAP-IV as a secondary measure of attention to allow comparisons to other studies that have used this popular rating scale.

Table 2.

CITT-ART Eligibility & Exclusion Criteria

| Eligibility Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

The d2 Test of Attention, a timed, objective test of selective and sustained attention, is included because it fits well within Mirsky's model.23 One of the most widely-accepted models of attention in neuropsychology, Mirsky's model divides attention into a number of components including encoding, focusing, executing responses, sustaining attention, shifting attention, and response stability.

CITT-ART Study Organization

The CITT-ART is a collaborative effort comprised of: 1) a study chair's office at the Salus University College of Optometry, 2) the Data Coordinating Center (DCC) housed at The Ohio State University College of Optometry, 3) the CITT-ART Reading Center, and 4) eight clinical sites (6 optometry, 1 ophthalmology, and 1 co-optometry and ophthalmology). Sites and investigators are listed in the Appendix.

Investigator Roles and Training/Certification

In addition to a principal investigator (PI) and site coordinator, each clinical site has personnel for the specific roles of masked examiner for vision testing (ME-VIS), masked examiner for attention and reading testing (ME-ART), and therapist. Persons serving as the ME-VIS must be a licensed optometrist or ophthalmologist. Qualifications to serve as the ME-ART include a bachelor's degree or higher with training in testing and measures. Qualified personnel typically include early interventionists, social workers, diagnostic education specialists, speech and language therapists, occupational and physical therapists, and optometrists with advanced residency training. Treatment activities are the responsibility of the therapist, a role filled by an optometrist, ophthalmologist, vision therapist, or orthoptist. All personnel are trained and certified to perform their specific study tasks as described in the CITT-ART Manual of Procedures and are required to update their certification yearly.

Patient Selection and Definition of CI

Complete inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 2. Major inclusion criteria include age 9 to 14 years, in grades 3–8, and symptomatic CI with the following characteristics: (1) a score of ≥16 on the CISS; (2) near exophoria at least 4 prism diopters (A) greater than at distance; (3) a receded NPC of ≥ 6 cm break, and (4) insufficient PFV (i.e., failing Sheard's criterion24 or PFV ≤ 15Δ base-out25) at near.

Eligibility Examination/Protocol

The CISS, vision testing, the WRAT-4 Word Reading subtest, and the K-BIT are administered by a study-certified optometrist or ophthalmologist and used to determine eligibility. At a subsequent visit, within 21 days of the initial eligibility testing, a ME-ART administers all reading testing.

Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey (CISS)

The CISS is administered to the child prior to any other testing and then repeated at the conclusion of the vision testing (the average of the 2 scores to be used for analyses). The 15 questions on the CISS are read aloud verbatim by the examiner while the child views a card containing the 5 possible answers (never, infrequently/not very often, sometimes, fairly often, and always). Responses for each question are scored as 0 (never) to 4 (always) and summed to obtain the total CISS score, with a possible score ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 60 (most symptomatic). A score ≥16 has been found to differentiate children with symptomatic CI from those with normal binocular vision.3,4

CI-Related Vision Testing

Distance visual acuity, cover testing at distance and near, the NPC, PFV, monocular amplitude of accommodation, monocular accommodative facility, vergence facility, random dot stereopsis at near, and a cycloplegic refraction (the latter if not done in prior 12 months) are measured.26

The Wide Range Achievement Test-4 (WRAT-4) Word Reading Subtest

The WRAT-4 Word Reading subtest measures word decoding. It consists of words, presented without a context (i.e., read in isolation rather than in a sentence), requiring the child to recognize and pronounce aloud the words. We recognize that successful CI treatment may not lead to improvement in reading fluency and comprehension in children who have severe reading disorders such as dyslexia,27–30 which has been reliably related to deficits in phonological processing and is characterized by significant difficulties reading single words without context. Therefore, we have restricted recruitment to children without significant single word reading deficits. We are using the WRAT-4 Word Reading subtest to identify and exclude children with these types of reading deficits because OBVAT would not be expected to affect reading comprehension in children with phonologically-based reading difficulties. We chose the WRAT-4 Word Reading Subtest because it has strong psychometric properties and is quick to administer (about 3 minutes).

The Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test-2 (KBIT-2)

The KBIT-2 is a norm-referenced test of both verbal and non-verbal intelligence (IQ) that can be used for screening purposes and assessing cognitive functioning when it is a secondary consideration.31 We are not using the Verbal subtests because children who have reading disabilities, often have artificially lowered verbal abilities because of their lack of exposure to vocabulary and world knowledge. Instead, we are using the Matrices (Nonverbal) subtest, which evaluates nonverbal conceptual reasoning and problem solving by assessing a child's ability to perceive relationships and complete analogies. Because pictures and abstract designs are used instead of words, nonverbal ability can be assessed even when language skills are limited. The Matrices subtest has excellent test-retest reliability and correlates well with similar but longer tests of nonverbal IQ.31 Only children with scores ≥ 70 are eligible for the study.

Children who meet all eligibility criteria (Table 1), including those related to the CISS score, vision testing, WRAT-4, and KBIT-2, subsequently return within 21 days for baseline reading testing and collection of attention measures.

Table 1.

Items on Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD Symptoms & Normal Behavior Scale (SWAN)

|

Baseline Reading and Attention Measures

A ME-ART administers the baseline reading testing described below. All reading testing is audio recorded and scored by the ME-ART after which the audiotapes are sent electronically to the Reading Center where the test results are verified.

Reading Comprehension Testing

Wechsler Individual Achievement Test 3rd Edition (WIAT-III)-Reading Comprehension Subtest

The WIAT-III is a nationally standardized achievement test that includes a Reading Comprehension subtest where the examinee reads a passage and then responds orally to several factual and inferential questions asked by the examiner. This controls for potentially confounding deficiencies in word identification and vocabulary. The Reading Comprehension subtest of the WIAT-III is the primary outcome measure for the study.

Gates-McGinitie 4 Reading Comprehension Subtest

The Gates-McGinitie 4 Reading Comprehension Subtest32 requires the examinee to respond to multiple-choice questions after reading passages independently. We chose this second test of reading comprehension because it measures comprehension using lengthy passages that are similar to textbooks typically read in school.

Other Reading Testing

To better understand the effects of CI therapy on reading comprehension, we administer other tests that examine reading domains known to support comprehension, namely word identification, phonological decoding, linguistic comprehension, and reading fluency. For example, reading comprehension suffers when too many cognitive resources are devoted to word recognition and decoding.33,34

The following four WIAT-III subtests are administered: 1) The Word Reading Subtest requires verbal pronunciation of real words one at a time from a word list that increases in difficulty. Accurate word identification is an essential skill for good comprehension. 2) The Pseudoword Decoding Subtest measures phonological skills by requiring oral pronunciation of nonwords from a word list that increases in difficulty. Because nonwords are not part of a child's sight vocabulary, the words can only be decoded using knowledge of sound-spelling correspondence rules for the English language. 3) The Oral Reading Fluency Subtest assesses oral reading accuracy and rate (words accurately read per minute). The task requires the child to read a passage aloud and then respond orally to comprehension questions. 4) The Listening Comprehension Subtest includes assessments of receptive vocabulary and oral discourse comprehension. For receptive vocabulary, the examinee listens to vocabulary words and then is asked to choose from a selection of four pictures the one that illustrate the word's meaning. For oral discourse comprehension, children listen to a recording of one or more sentences of text and respond to oral questions about the text.

In addition to aforementioned standardized testing, changes in general reading proficiency are tracked through the use of Curriculum-Based Measurements (CBM) that are commonly used by school districts to monitor reading progress. The CBMs are administered at baseline and all follow-up examinations. The first, the R-CBM, provides a count of the number of words read correctly in 1 minute of oral reading; three separate passages are administered. The Reading Maze test measures how well children understand the text that they read silently by having them read passages with omitted words, with the requirement that they circle the correct omitted word (from among three word choices in parenthesis) that fits best with the rest of the reading passage.

Attention-Related Measures

Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD Symptoms and Normal Behavior (SWAN)

The SWAN is a behavior rating scale that assesses symptoms of ADHD in children and adolescents. It is based on DSM-5 criteria for ADHD diagnosis and measures inattentive, hyperactive, and impulsive behaviors. Observers are asked to compare the child's behavior in a variety of settings to other children of the same age using a 7-point scale that ranges from “far below average” to “far above average.” Higher scores indicate greater symptoms. The SWAN is completed by the parent and the child's teacher at baseline and outcome. The parent rating is the primary outcome measure of attention.

SNAP-IV Parent Rating Scale

The Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham (SNAP) scale is an 18-item behavior rating scale. One item for each of the 18 symptoms contained in the DSM-IV diagnosis of ADHD is included. Each item is scored on a 0 to 3 scale (0 = not at all, 1 = just a little, 2 = pretty much, 3 = very much). Because the SNAP has been used in a number of treatment studies of ADHD,35,36 we included it as a secondary measure of attention.

d2 Test of Attention

The d2 test measures processing speed, rule compliance, and quality of performance in response to the discrimination of similar stimuli, thereby allowing for an estimation of individual attention and concentration performance. The one-page test form has 14 lines of 10 different symbols, which are made up of combinations of the letters “d” and “p” with one to four dashes arranged either above or below the letter. The child is given 20 seconds per line to cross out each “d” with two dashes in any combination above or below the letter. Each line can be scored separately allowing for a measure of fatigue.

Academic Functioning-Related Testing

The Homework Problems Checklist (HPC)37 and the Academic Behavior Survey (ABS)7 are completed by the parent at baseline and all follow-up visits. The Documentation of School Reading Instruction (DSRI) is completed by the teacher at the primary outcome examination and 1-year follow-up exam.

Homework Problems Checklist (HPC)

The HPC is a 20-item survey that is commonly used as an outcome measure for assessing the impact of interventions on homework problem behaviors.37 The HPC has two distinct factors - inattention/avoidance of homework and poor productivity/non-adherence to homework rules.38,39 The inattention/avoidance factor includes items such as ‘puts off doing homework’ and ‘waits until the last minute, ’ while the poor productivity/non-adherence factor includes items such as ‘fails to bring home necessary materials’ and ‘doesn’t know exactly what homework has been assigned. ’ Parents rate the frequency of occurrence of the behaviors on a 4-point scale (0=never, 1= at times, 2=often, 3=very often).

Academic Behavior Survey (ABS)

The ABS is a 6-item survey designed to measure the frequency of adverse academic behaviors and parental worry about academic performance.7 Items are: difficulty completing assignments at school, difficulty completing homework, avoiding reading and studying, making careless mistakes, inattentiveness or distraction during reading, and parental worry about school performance. Ratings are made on a 5-point scale.

Documentation of School Reading Instruction (DSRI)

The DSRI is a brief teacher questionnaire developed to document the amount and nature of reading instruction and intervention provided to a student by his or her school. We have adapted a version of a DSRI used in past reading intervention field studies for use in this study.40

Randomization

Using a permuted block design stratified by site and ADHD-diagnosis, eligible children are randomly assigned to either OBVAT or OBPT in a 2:1 ratio, respectively. Randomization does not occur until after completion of the Reading & Attention Baseline visit. Once randomized, participants remain in the study and are included in the analyses regardless of whether the assigned treatment is received or if alternative treatments are undertaken (i.e., the intention to treat principle is followed).

Treatment and Follow-Up Visits

Participants in both treatment groups attend 16 weekly, 60-minute, office-based treatment sessions administered by a trained therapist, and are prescribed procedures to practice at home, for 15 minutes, 5 times per week.

Office-based Vergence/Accommodative Therapy with Home Reinforcement (OBVAT)

The OBVAT protocol is a well-accepted approach for the treatment of CI41 and has been successfully implemented in four previous CITT studies.6,12,18,42

Office-based Placebo Therapy with Home Reinforcement (OBPT)

The OBPT protocol that we successfully implemented43,44in our previous clinical trials6,12,42 is being used with several modifications. All OBPT procedures are designed to simulate real vision therapy/orthoptics procedures yet not stimulate vergence, accommodation, or small saccadic eye movement skills beyond those that normally occur in real life.

Repeated Assessments

Masked follow-up vision examinations are performed after every 4 weeks of therapy, with the primary outcome examination occurring the week following the last week of treatment (after 16 weeks of treatment). All participants are re-examined 1 year after treatment completion to assess the long-term effects on reading and attention.

Maintenance Treatment for Participants Not Symptomatic at the 16-week Outcome Examination

Consistent with standard care, all participants who are no longer symptomatic (CISS <16) at the 16-week outcome visit are assigned maintenance therapy consisting of one therapy procedure to be performed 15 minutes, once per week, for 3 months at home, after which maintenance therapy is discontinued. All participants are seen for long-term follow-up assessments 1 year after completion of treatment.

Management of Participants Who are Symptomatic at the 16-week Outcome Examination

Additional therapy is offered at no cost to all participants who are still symptomatic at the 16-week outcome examination. OBVAT is offered to those originally assigned to OBPT. Treatment options including lenses, prism, more OBVAT, or home-based treatment are offered to participants in the OBVAT group who are still symptomatic. The amount of such treatment needed will be tracked as an additional outcome measure and to be used as a covariate.

Obtaining Teacher Ratings

Although obtaining teacher ratings increases the complexity of the study, the potential benefits are significant. Teacher rating scales are optimal practice in studies of children treated for ADHD and are considered beneficial because teachers: 1) are less biased than parents because there is a difference between the teacher-child relationship and parent-child relationship, 2) have more experience with other children of the same age and thus they have a more objective basis for comparison, and 3) interact with children in their primary learning environment.

Quality Assurance Activities

The CITT-ART Executive Committee has primary responsibility for assuring the quality of the study data collected and ultimately to be reported. The major quality assurance features are the training and certification of clinical site personnel, standardization of procedures used to diagnose and treat CI, inclusion of a centralized Reading Center for scoring of reading assessments, standardization of data collection forms and procedures, development of protocols to maintain masking of both examiners and participants, and the use of separate masked examiners to obtain vision/ clinical measures versus attention/reading measures. Monthly conference calls are held for all investigators and yearly site visits are made to assess adherence to the study protocols.

Data Management

All data is processed centrally at the CITT-ART DCC. Concurrent data processing is ongoing so that timely feedback may be provided to investigators in regards to any protocol violations.

Statistical Analyses

All data analyses will be performed using the SAS software system.45 Unless specifically stated otherwise, an a-level of 0.05 will be used. The trial's primary outcome is based on a comparison of changes in the WIAT-III reading comprehension scores between the OBVAT and OBPT groups, obviating the need to correct for multiple tests with regard to this analysis. Data analysis will use the intention to treat principle, thus providing unbiased comparison of the treatment arms.

Descriptive demographic characteristics, visual function findings, and reading scores of participants will be compared to assess the effectiveness of randomization in balancing the treatment arms. For continuous measures, the means and standard deviations will be calculated for each treatment arm and two-sample t-tests will be used to compare the treatments. The percentage of participants falling into each level of all categorical measures will be calculated and compared using chi-square tests. Because the study is not powered to detect small, yet clinically meaningful, inter-group differences in these measures, visual inspection of the descriptive statistics will also be performed to identify such differences. Factors identified using either method (statistical comparison or visual inspection) will be identified as confounders in the analyses.

The primary outcome is to determine the effect of treatment on reading performance after 16 weeks of OBVAT versus OBPT. Specifically, we will compare change in WIAT-III reading comprehension (primary outcome measure), and in GMRT reading comprehension, and WIAT-III word reading, pseudoword decoding, oral reading fluency, and listening comprehension scores (secondary outcome measures) between groups. Hierarchical linear modeling techniques with a random effect for enrollment site will be used. We also will examine the correlation of changes in CI-symptoms and ophthalmic signs of CI with reading outcomes using hierarchical linear modeling and controlling for baseline measures and any other identified covariate(s) and interactions. Finally, we will determine if any gains in reading performance observed after 16 weeks of treatment are sustained after 1-year of follow-up.

The effect of treatment on teacher- and parent-rated measures of attention using the SWAN and the SNAP-IV will be determined using hierarchical linear modeling with a random effect for enrollment site and controlling for baseline measures and any other identified covariates. Analysis will include an indicator for time (4, 8, 12 or 16 week) and rater for the SWAN. Simple correlation analysis will be used to examine the relationship of changes in CI-symptoms and ophthalmic signs of CI with changes in attention outcomes. Finally, we will determine if any gains in attention observed after 16 weeks of treatment are maintained after 1-year of follow-up (i.e. long-term effectiveness). When sample size allows, hierarchial models will be used to investigate demographic and clinical factors as predictors of long-term effectiveness.

Study Strengths

The CITT-ART is the first randomized clinical trial designed to evaluate the effect of successful treatment of symptomatic CI in children on reading and attention. Study strengths include a multi-disciplinary group of investigators, including those with expertise in convergence insufficiency and its treatment, reading, ADHD, and the conduct of clinical trials involving children. The randomized trial design and masking of investigators and participants to treatment assignment will minimize bias. The use of the placebo therapy arm will allow us to determine if any treatment effects found are merely due to placebo effect or regression to the mean. The 1-year follow up will allow us to determine if OBVAT has a long-term effect on reading and attention.

The results of the study will contribute to a better understanding of the relationship between CI and reading and attention. Parents, eye care professionals, educators, and other health care providers will be better able to make informed decisions as they care for children with reading and attention problems. Results may also generate additional hypothesis and guide the development of other scientific investigations regarding the relationships between visual dysfunctions and other developmental disorders in children.

Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial (CITT) Investigator Group

The Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial (CITT) Investigator group was first conceived in December 1992 at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Optometry. At that time the group used the acronym CIRS (Convergence Insufficiency Reading Study). The ultimate goal of the group was to complete a randomized clinical trial to determine the effect on reading of successful vision therapy for symptomatic CI. It soon became evident that many interim steps would be required to achieve this objective. In 1998 at the Summer Invitational Research Institute Meeting in Columbus, OH we officially changed our group name to the Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial (CITT) Investigator group. This group spent about 10 years performing pilot studies in preparation for a major submission to the National Eye Institute (NEI).

In October 2000, the NEI funded our first project with a small, R21 planning grant. This grant helped us complete the CITT-Base-In Study, and a randomized clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of office-based vision therapy to placebo therapy and home-based pencil pushups in both children and adults. The results of these studies gave us the experience and credibility to apply for a large U10 grant from the NEI which was funded ($6.1 million) in 2004 and completed in 2008. This study, known as the CITT demonstrated that office-based vision therapy is significantly more effective than home-based vision therapy and should be the primary treatment option for symptomatic CI in children. After 6 more years of preparation and pilot studies we were again funded by the NEI ($8 million) for the study described in this article, which we named CITT-ART. This study is designed to answer the original question asked over two decades ago in 1992.

Over the past 23 years the group has published 22 articles, has 42 published abstracts, and CITT investigators have presented our study results nationally and internationally on many occasions. Well over 100 investigators from 8 Colleges of Optometry and several ophthalmological institutions have participated. The outstanding and dedicated investigators at the various clinical sites were the key to the success of our studies. The current CITT-ART leadership includes: Mitchell Scheiman, OD (Study Chair); G. Lynn Mitchell, MAS (Director of the Data Coordinating Center); Susan Cotter, OD, MS (Vice Chair); Marjean Kulp, OD, MS (Vice Chair); Eugene Arnold, MD (Consultant - Attention expert), Carolyn Denton, EdD (Consultant - Reading Expert, Eric Borsting, OD, MSEd (Consultant - Reading Expert), Richard Hertle, MD (Pediatric Ophthalmologist), Christopher Chase, PhD (Director of Reading Data Center). A full list of investigators is included at the end of this article.

Clinical Sites

Personnel are listed as (PI) for principal investigator, (CC) for clinic coordinator, (ME-VIS) for the masked examiner who performs the vision testing, (ME-ART) for the masked examiner that performs reading and attention testing, and (VT) for therapist. Positions at the Data Coordinating Center include data entry operators (DE)

Study Center: Southern California College of Optometry at Marshall B Ketchum University

Susan Cotter, OD, MS (PI); Carmen Barnhardt, OD, MS (VT); Eric Borsting, OD, MSEd (ME-ART); Angela Chen, OD, MS (VT); Raymond Chu, OD, MS (ME-VIS); Kristine Huang, OD, MPH (ME-VIS and ME-ART); Susan Parker (CC)

Study Center: Bascom Palmer Eye Institute

Susanna Tamkins, OD (PI); Craig McKeown, MD (co-PI); Naomi Aguilera, OD (VT); Hilda Capo, MD (ME-VIS); Kara Cavuoto, MD (ME-VIS); Monica Dowling, PhD (ME-ART); Miriam Farag, OD (VT); Vicky Fischer, OD (VT); Carolina Manchola-Orozco, BA (CC); Natalie Townsend, OD (ME-VIS); Maria Martinez, BS (CC)

Study Center: Pennsylvania College of Optometry at Salus University

Michael Gallaway, OD (PI); Mark Boas, OD (VT); Zachary Margolies, MSW, LSW (ME-ART); Jenny Myung, OD (ME-VIS); Karen Pollack (CC); Mitchell Scheiman, OD (ME-VIS); Ruth Shoge, OD (ME-VIS); Lynn Trieu, OD, MS (VT), Luis Trujillo, OD (VT); Erin Jenewein, OD, MS (VT)

Study Center: SUNY College of Optometry

Erica Schulman, OD (PI); Danielle lacono, OD (ME-VIS); Steven Larson, OD (ME-ART); Sara Meeder, BA (CC); Steven Ritter, OD (VT); Audra Steiner, OD (ME-VIS); Marilyn Vricella, OD (ME-VIS); Jeff Cooper, OD, MS (PI through April 2015); Valerie Leung, BOptom (CC); Alexandria Stormann, RPA-C (CC)

Study Center - The Ohio State University College of Optometry

Marjean Kulp, OD, MS (PI); Michelle Buckland, OD, MS (ME-VIS); Catherine McDaniel, OD, MS (ME-VIS); Ann Morrison, OD (ME-VIS); Tamara Oechslin, OD, MS (VT); Julie Preston, OD, PhD (ME-ART); Kathleen Reuter, OD (VT); Nancy Stevens, MS (CC), Andrew Toole, OD, PhD (VT); Douglas Widmer, OD (ME-VIS); Aaron Zimmerman, OD, MS (ME-VIS); Micahel Early, OD, PhD, ME-VIS

Study Center: UAB School of Optometry

Kristine Hopkins, OD (PI); Kristy Domnanovich, PhD (ME-ART); Marcela Frazier, OD, MPH (ME-VIS); John Houser, PhD (ME-ART); Sarah Lee, OD, MS (VT); Katherine Weise, OD, MBA (ME-VIS); Michelle Bowen, BA (through July 2015); Wendy Marsh Tootle, OD, MS (through April 2015); Oakley Hayes, OD, MS (VT; through May 2015); Christian Spain (CC); Candice Turner, OD (ME-ART)

Study Center: Akron Children's Hospital

Richard Hertle, MD (PI); Penny Clark (ME-ART); Kelly Culp, RN (CC); Kathy Fraley, CMA (ME-ART); Drusilla Grant, OD (VT); Nancy Hanna, MD (ME-VIS); Stephanie Knox (CC); William Lawhon, MD (ME-VIS); Casandra Solis, OD (VT); Simone Li, OD (VT); Sarah Mitcheff (ME-ART); Samantha Zaczyk, OD (VT)

Study Center: NOVA Southeastern University

Rachel Coulter, OD (PI); Deborah Amster, OD (ME-VIS); Annette Bade, OD, MCVR (CC); Gregory Fecho, OD (VT); Erin Jenewein, OD, MS (VT); Pamela Oliver, OD, MS (ME-ART); Nicole Patterson, OD, MS (ME-ART); Jacqueline Rodena, OD (ME-VIS); Yin Tea, OD (VT); Dana Weiss, MS (ME-ART); Surbhi Bansal, OD (ME-VIS); Laura Falco, OD (ME-VIS); Rita Silverman, MPA (ME-ART); Julie Tyler, OD (CC); Lauren Zakaib, MS (ME-ART)

CITT Study Chair

Mitchell Scheiman, OD (Study Chair); Karen Pollack (Study Coordinator); Susan Cotter, OD, MS (Vice Chair); Marjean Kulp, OD, MS (Vice Chair)

CITT Data Coordinating Center

Gladys Lynn Mitchell, MAS, (PI); Gloria Scott-Tibbs (PC); Victor Vang (DE)

National Eye Institute, Bethesda, MD

Maryann Redford, DDS

CITT Executive Committee

Mitchell Scheiman, OD; G. Lynn Mitchell, MAS; Susan Cotter, OD, MS (Vice Chair); Marjean Kulp, OD, MS (Vice Chair); Eugene Arnold, MD (Consultant-attention expert), Carolyn Denton, EdD (Consultant - Reading Expert, Eric Borsting, OD, MSEd Consultant- Reading Expert, Richard Hertle, MD, Christopher Chase, PhD (Chair Reading Data Center).

Data and Safety Monitoring Committee

Marie Diener-West, PhD (Chair); William V Good, MD; J. David Grisham, OD, MS; Christopher J. Kratochvil, MD; Dennis Revicki, PhD; Jeanne Wanzek, PhD

Footnotes

All statements are the author's personal opinion and may not reflect the opinions of the College of Optometrists in Vision Development, Vision Development & Rehabilitation or any institution or organization to which the author may be affiliated. Permission to use reprints of this article must be obtained from the editor. Copyright 2015 College of Optometrists in Vision Development. VDR is indexed in the Directory of Open /Access Journals. Online access is available at http://www.covd.org.

References

- 1.Letourneau JE, Ducic S. Prevalence of convergence insufficiency among elementary school children. Can J Optom. 1988;50:194–197. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rouse MW, Borsting E, Hyman L, et al. Frequency of convergence insufficiency among fifth and sixth graders. Optom Vis Sci. 1999;76:643–649. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199909000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rouse M, Borsting E, Mitchell GL, et al. Validity of the convergence insufficiency symptom survey: A confirmatory study. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86:357–363. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181989252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borsting EJ, Rouse MW, Mitchell GL, et al. Validity and reliability of the revised convergence insufficiency symptom survey in children aged 9–18 years. Optom Vis Sci. 2003;80:832–838. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200312000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borsting E, Rouse MW, De Land PN. Prospective comparison of convergence insufficiency and normal binocular children on CIRS symptom surveys. Convergence Insufficiency and Reading Study (CIRS) group. Optom Vis Sci. 1999;76(4):221–228. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199904000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial Investigator Group. A randomized clinical trial of treatments for symptomatic convergence insufficiency in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1336–1349. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.10.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rouse M, Borsting E, Mitchell GL, et al. Academic behaviors in children with convergence insufficiency with and without parent-reported ADHD. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86:1169–1177. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181baad13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borsting E, Rouse M, Chu R. Measuring ADHD behaviors in children with symptomatic accommodative dysfunction or convergence insufficiency: a preliminary study. Optometry. 2005;76:588–592. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borsting E, Mitchell GL, Scheiman M, et al. Treatment of symptomatic convergence insufficiency improves attention In school-aged children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52 ARVO E-Abstract 6375. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Granet DB, Gomi CF, Ventura R, Miller-Scholte A. The relationship between convergence insufficiency and ADHD. Strabismus. 2005;13:163–168. doi: 10.1080/09273970500455436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheiman M, Gwiazda J, Li T. Non-surgical interventions for convergence insufficiency. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011;(3):CD006768. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006768.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheiman M, Mitchell GL, Cotter S, et al. A randomized trial of the effectiveness of treatments for convergence insufficiency in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:14–24. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borsting E, Mitchell GL, Kulp MT, et al. Improvement in academic behaviors after successful treatment of convergence insufficiency. Optom Vis Sci. 2012;89:12–18. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e318238ffc3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atzmon D, Nemet P, Ishay A, Kami E. A randomized prospective masked and matched comparative study of orthoptic treatment versus conventional reading tutoring treatment for reading disabilities in 62 children. Binocul Vis Q Eye Muscle Surg. 1993;8:91–106. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dusek W, BK P, Mcclelland JF. A survey of visual function in an Austrian population of school-age children with reading and writing difficulties. BMC Ophthal:[serial online] 2010. 2010 May 25;10:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borsting E, Mitchell GL, Arnold LE, et al. Behavioral and emotional problems associated with convergence insufficiency in children: An open trial. J Atten Disord. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1087054713511528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SH, Moon BY, Cho HG. Improvement of vergence movements by vision therapy decreases K-ARS scores of symptomatic ADHD children. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014;26:223–227. doi: 10.1589/jpts.26.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheiman M, Chase C, Mitchell GL, et al. Assoc Research Vis Ophthalmol. Ft. Lauderdale, FL. p. 6375/D809; 2011. The effect of successful treatment of symptomatic convergence lisufficiency on reading achievement in school-aged children. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perfetti C, Landi N, Oakhill J. The acquisition of reading comprehension skill. In: Snowling MJ, Hulme C, editors. The Science of Reading: A Handbook. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell; 2005. pp. 227–247. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adolph SM, Catts HW, Little TD. Should the simple view of reading include a fluency component? Read Writ. 2006;19:933–958. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oakhill JV, Cain K, Bryant PE. The dissociation of word reading and text comprehension: Evidence from component skills. Lang Cognitive Proc. 2003;18:443–468. [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirsky AF, Pascualvaca DM, Duncan CC, French LM. A model of attention and its relation to ADHD. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 1999;5:169–176. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheard C. Zones of ocular comfort. Am J Optom. 1930;7:9–25. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morgan M. The clinical aspects of accommodation and convergence. Am J Optom Arch Am Acad Optom. 1944;21:301–313. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial Investigator Group. The Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial: Design, methods, and baseline data. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15:24–36. doi: 10.1080/09286580701772037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vellutino FR, Fletcher JM. Developmental dyslexia. In: Snowling MJ, Hulme C, editors. The Science of Reading: A Handbook. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell; 2005. pp. 362–378. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaywitz SE, Morris R, Shaywitz BA. The education of dyslexic children from childhood to young adulthood. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:451–475. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaywitz SE. Overcoming dyslexia. New York: Alfred A. Knopf; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fletcher JM, Lyon GR, Fuchs LS, Barnes MA. Learning disabilities: From identification to intervention. New York: Guilford; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children Second Edition. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacGinitie W, MacGinitie R, Maria K, Dreyer L, Hughes K. Gates-MacGinitie Reading Tests-4. Itasca, IL: Riverside; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.LaBerge D, Samuels SJ. Toward a theory of automatic information processing in reading. Cog Psychol. 1974;6:293–323. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shankweiler D, Lundquist E, Katz L, et al. Comprehension and decoding: Patterns of association in children with reading difficulties. Sci Stud Read. 1999;3 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Correia Filho AG, Bodanese R, Silva TL, Alvares JP, Aman M, Rohde LA. Comparison of risperidone and methylphenidate for reducing ADHD symptoms in children and adolescents with moderate mental retardation. J Am Acad Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:748–755. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000166986.30592.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.The MTA Cooperative Group. A 14-Month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:1073–2086. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anesko KM, Schoiock G, Ramirez R, Levine FM. The Homework Problem Checklist: Assessing children’s home-work problems. Behavioral Assessment. 1987;9:179–185. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Power TJ, Werba BE, Watkins MW, Angelucci JG, iraldi RB. Patterns of parent-reported homework problems among adhd-referred and non-referred children. Sch Psychol Q. 2006;21:13–33. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langberg JM, Arnold LE, Flowers AM, Altaye M, Epstein JN, Molina BSG. Assessing homework problems in children with ADHD: Validation of a parent-report measure and evaluation of homework performance patterns. School Ment Health. 2010;2:3–12. doi: 10.1007/s12310-009-9021-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mathes PG, Denton CA, Fletcher JM, Anthony JL, Francis DJ, Schatschneider C. The effects of theoretically different instruction and student characteristics on the skills of struggling readers. Reading Res Q. 2005;40:148–182. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheiman M, Wick B. Clinical Management of Binocular Vision: Heterophoric, Accommodative and Eye Movement Disorders. 3rd. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheiman M, Mitchell GL, Cotter S, et al. A randomized clinical trial of vision therapy/orthoptics versus pencil pushups for the treatment of convergence insufficiency in young adults. Optom Vis Sci. 2005;82:583–595. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000171331.36871.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kulp M, Mitchell GL, Borsting E, et al. Effectiveness of placebo therapy for maintaining masking in a clinical trial of vergence/accommodative therapy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:2560–2566. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kulp M, Borsting E, Mitchell GL, et al. Feasibility of using a placebo vision therapy/orthoptics control in a multicenter clinical trial. Optom Vis Sci. 2008;85:255–261. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e318169288a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grisham JD. Visual therapy results for convergence insufficiency: a literature review. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1988;65:448–454. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198806000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cooper J, Duckman R. Convergence insufficiency: incidence, diagnosis, and treatment. J Am Optom Assoc. 1978;49:673–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]