Abstract

The Phytophthora sojae avirulence gene Avr3a encodes an effector that is capable of triggering immunity on soybean plants carrying the resistance gene Rps3a. P. sojae strains that express Avr3a are avirulent to Rps3a plants, while strains that do not are virulent. To study the inheritance of Avr3a expression and virulence towards Rps3a, genetic crosses and self-fertilizations were performed. A cross between P. sojae strains ACR10 X P7076 causes transgenerational gene silencing of Avr3a allele, and this effect is meiotically stable up to the F5 generation. However, test-crosses of F1 progeny (ACR10 X P7076) with strain P6497 result in the release of silencing of Avr3a. Expression of Avr3a in the progeny is variable and correlates with the phenotypic penetrance of the avirulence trait. The F1 progeny from a direct cross of P6497 X ACR10 segregate for inheritance for Avr3a expression, a result that could not be explained by parental imprinting or heterozygosity. Analysis of small RNA arising from the Avr3a gene sequence in the parental strains and hybrid progeny suggests that the presence of small RNA is necessary but not sufficient for gene silencing. Overall, we conclude that inheritance of the Avr3a gene silenced phenotype relies on factors that are variable among P. sojae strains.

Introduction

The genus Phytophthora includes some 120 species of plant pathogenic organisms [1,2]. Root and stem rot of soybean caused by Phytophthora sojae is a destructive, soil-borne plant disease that has spread globally since its identification in North America in the 1950s [3,4]. Phytophthora sojae is a diploid, homothallic organism. Self-fertilized oospores can develop from one strain, while out-crossing between strains results in F1 hybrids. It is not possible to distinguish hybrid progeny from self-fertilized progeny without the use of strain-specific markers. The first experimental hybridizations of P. sojae were identified by crossing strains differing in drug resistance, but now DNA markers are routinely used for tracking parentage [5–10]. Many different traits and markers have been followed in F1 and F2 progeny. Segregation patterns usually follow Mendelian rules but loss of heterozygosity in F1 or F2 progeny commonly occurs in P. sojae, and in other Phytophthora species, and can result in unusual inheritance patterns [9,11–15].

The disease caused by P. sojae is managed through the selection, breeding, and deployment of soybean cultivars with enhanced resistance. This process relies on naturally occurring resistance (Rps) genes conferring race-specific immunity to P. sojae, and on quantitative trait loci (QTL) that condition partial resistance [16–19]. Variation of P. sojae makes management difficult, because it can evolve rapidly into new strains that defeat Rps gene mediated immunity. Pathogen effectors that trigger immunity in the host are avirulence (Avr) factors. Changes to Avr genes that result in escape from host immunity cause gain of virulence.

The P. sojae Avr genes identified to date include Avr1a [20], Avr1b [21], Avr1c [22], Avr1d [23,24], Avr1k [25], Avr3a/5 [26], Avr3b [27], Avr3c [28], and Avr4/6 [29]. Strain specific gain of virulence changes are diverse but transcriptional polymorphisms are common, having been observed for Avr1a, Avr1b, Avr1c, and Avr3a/5. Loss of effector gene mRNA may be due to conventional mutations that disable transcription but emerging results suggest that epigenetic changes can also underlie these polymorphisms [30–32].

The Avr3a/5 locus of P. sojae was identified through genetic mapping and transcriptional profiling [20,26]. Two independent soybean genes conditioning resistance to P. sojae, Rps3a and Rps5, differentially recognize allelic variants at the Avr3a/5 locus. Escape from Rps3a mediated immunity is caused by transcriptional variation. Transcripts of Avr3a mRNA are present in avirulent strains and progeny but not in the virulent strains and progeny [26]. Crossing of P. sojae strain P6497 (avirulent to Rps3a) and strain P7064 (virulent to Rps3a) and analysis of F1 and F2 progeny demonstrated that expression of Avr3a and avirulence to Rps3a segregate normally as dominant Mendelian traits in this cross [20]. The P. sojae strain P7064 harbors insertion and deletion mutations in the promoter of Avr3a that likely interfere with transcription and cause it to segregate as a recessive allele. In contrast, crosses between P. sojae strain P7076 (avirulent to Rps3a) and strain ACR10 (virulent to Rps3a) result in transgenerational gene silencing of Avr3a and gain of virulence to Rps3a in all F1 and F2 progeny, despite that the Avr3a alleles themselves segregate normally [30]. This past study additionally showed that small RNA (sRNA) molecules arising from the Avr3a gene are abundant in gene silenced parental strains and progeny, but are absent or reduced in those that express the gene.

Experiments described here further explore the phenomenon of naturally occurring gene silencing of Avr3a in its inheritance in P. sojae. We test the meiotic stability of gene silencing of Avr3a over multiple generations and determine whether gene silenced alleles of Avr3a gain the capability to silence expressed alleles of other strains. We also construct a new cross of P. sojae strains ACR10 X P6497 and follow the inheritance of virulence to Rps3a, the expression of Avr3a, and the presence of sRNA, in parental strains and hybrid progeny. Overall, our results indicate that strain-specific epistatic factors play a role in controlling the expression of Avr3a in hybrid progeny.

Results

Gene silencing of Avr3a is meiotically stable over multiple generations in progeny from a cross of ACR10 X P7076

To study the meiotic stability of gene silencing, F4 progeny were developed by self-fertilization of four different F3 progeny. The four different F3 (F3-40, F3-60, F3-83, and F3-87) isolates were selected randomly from progeny with the genotype Avr3aP7076/Avr3aP7076, and self-fertilized to produce F4 progeny. From each of the four F3 progeny, four germinating oospores were isolated to develop F4 progeny. Therefore a total of 16 F4 progeny were generated. Virulence assays were performed on test (Rps3a) and control (rps3a) soybean plants, and the cultures were assessed for the presence of Avr3a mRNA transcript by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The virulence assays show that 15/16 of the progeny are virulent towards soybeans carrying the Rps3a gene, but one F4 lost general virulence or pathogenicity, being avirulent to both test (Rps3a) and control (rps3a) plants (Table 1). There are no detectable Avr3a mRNA transcripts among all (16/16) tested F4 progeny including the avirulent individual.

Table 1. Virulence outcomes and Avr3a transcript detection in F3 and F4 progeny from P. sojae cross ACR10 X P7076.

| F3 progeny1 | F4 progeny1 | Virulence on Rps3a (L83-570)2 | Virulence on rps3a (Williams)2 | Assigned phenotype3 | Avr3a mRNA transcript (RT-PCR)4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F3-40 | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F4-40(3) | 9 | 15 | NP | - | |

| F4-40(4) | 43 | 45 | V | - | |

| F4-40(5) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F4-40(7) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F3-60 | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F4-60(1) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F4-60(2) | 55 | 60 | V | - | |

| F4-60(4) | 53 | 56 | V | - | |

| F4-60(5) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F3-87 | 58 | 60 | V | - | |

| F4-87(1) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F4-87(2) | 55 | 53 | V | - | |

| F4-87(3) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F4-87(4) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F3-83 | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F4-83(1) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F4-83(2) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F4-83(3) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F4-83(4) | 59 | 60 | V | - |

1All progeny originally derived from F2 individuals homozygous for the Avr3aP7076 allele

2 Number of dead plants from a total of 60 challenged, representing the sum from two independent virulence assays of 30 plants each.

3 Phenotypes: A, avirulent; V, virulent; NP, non-pathogenic.

4 Symbol (+) positive for Avr3a mRNA, (-) negative for Avr3a mRNA. All samples were positive for control Actin mRNA. Summary of results from two independent biological replicates.

Similarly, to develop F5 progeny, one individual from each of the four different F4 strains was selected and processed for self-fertilization. The isolate that had lost virulence to control plants was excluded, but otherwise the four individuals were selected randomly. From each F4 self-fertilization, four oospores were isolated and developed into F5 progeny, thus making a total of 16 F5 progeny. Virulence assays were performed on test (Rps3a) and control (rps3a) soybean plants, and the cultures were tested for the presence of Avr3a transcript by RT-PCR. The virulence assay results show that 15/16 of the F5 progeny are virulent towards soybeans carrying the Rps3a gene, but again one F5 lost general virulence or pathogenicity, since it is avirulent to both test (Rps3a) and control (rps3a) plants (Table 2). There are no detectable Avr3a mRNA transcripts among all (16/16) tested F5 progeny. Although one isolate in each F4 and F5 progeny lost their general virulence towards soybean plants with or without Rps3a, it was not due to changes in expression of the Avr3a transcript. Therefore, Avr3a gene silencing was stable in all F4 and F5 progeny.

Table 2. Virulence outcomes and Avr3a transcript detection in F4 and F5 progeny from P. sojae cross ACR10 X P7076.

| F4 progeny1 | F5 progeny1 | Virulence on Rps3a (L83-570)2 | Virulence on rps3a (Williams)2 | Assigned phenotype3 | Avr3a mRNA transcript (RT-PCR)4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F4-40(7) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F5-40(1) | 20 | 12 | NP | - | |

| F5-40(2) | 59 | 57 | V | - | |

| F5-40(3) | 60 | 59 | V | - | |

| F5-40(4) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F4-60(5) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F5-60(1) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F5-60(2) | 53 | 52 | V | - | |

| F5-60(3) | 55 | 56 | V | - | |

| F5-60(4) | 54 | 47 | V | - | |

| F4-87(1) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F5-87(1) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F5-87(2) | 56 | 58 | V | - | |

| F5-87(3) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F5-87(4) | 45 | 46 | V | - | |

| F4-83(3) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F5-83(1) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F5-83(2) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F5-83(3) | 60 | 60 | V | - | |

| F5-83(4) | 60 | 60 | V | - |

1All progeny originally derived from F2 individuals homozygous for the Avr3aP7076 allele

2 Number of dead plants from a total of 60 challenged, representing the sum from two independent virulence assays of 30 plants each.

3 Phenotypes: A, avirulent; V, virulent; NP, non-pathogenic.

4 Symbol (+) positive for Avr3a mRNA, (-) negative for Avr3a mRNA. All samples were positive for control Actin mRNA. Summary of results from two independent biological replicates.

Gene silencing of Avr3a is released by out-crossing

To determine whether silenced alleles of Avr3aP7076 have the capacity to silence expressed alleles of other strains of P. sojae, a test cross was performed between P. sojae strains P6497 X [F1(ACR10 X P7076)]. A total of 110 oospores were isolated from a cross of P6497 X [F1-62(ACR10 X P7076)]. Due to the identical Avr3a sequence of P6497 and ACR10, hybrids of interest (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076 or AvraP6497/Avr3aACR10) were identified using three different co-dominant DNA markers. A total of 14 Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076 and 17 Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10 hybrids were identified from the 110 progeny of this cross. Virulence testing of the 31 hybrids indicated that 30 are avirulent towards test (Rps3a) plants, whereas one (progeny number 12; Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) is virulent (Table 3). Most (30/31) isolates retained virulence towards control (rps3a) plants. Analysis of Avr3a mRNA levels by RT-PCR showed that all 31 cultures produce Avr3a transcripts. However, the Avr3a mRNA level is reduced in progeny number 12 that is virulent on Rps3a plants (Fig 1).

Table 3. Genotypes, virulence outcomes and Avr3a transcript detection in test cross progeny of P6497 X F1-62 (ACR10 X P7076).

| Test cross progeny number and Avr3a genotype | Virulence on Rps3a(L83-570)1 | Virulence on rps3a (Williams)1 | Assigned phenotype2 | Avr3a mRNA transcript(RT-PCR)3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 2 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 7 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 12 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 60 | 60 | V | + |

| 14 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 1 | 60 | A | + |

| 17 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 18 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 27 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 2 | 60 | A | + |

| 30 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 31 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 40 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 51 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 52 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 0 | 58 | A | + |

| 53 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 61 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 0 | 0 | NP | + |

| 62 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 63 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 0 | 55 | A | + |

| 64 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 0 | 56 | A | + |

| 65 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 69 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 72 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 74 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 84 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 0 | 59 | A | + |

| 96 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 98 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 100 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 101 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 106 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 107 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 108 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

| 109 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 0 | 60 | A | + |

1 Number of dead plants from a total of 60 challenged, representing the sum from two independent virulence assays of 30 plants each.

2 Phenotypes: A, avirulent; V, virulent; NP, non-pathogenic.

3 Symbol (+) positive for Avr3a mRNA, (-) negative for Avr3a mRNA. All samples were positive for control Actin mRNA. Summary of results from two independent biological replicates.

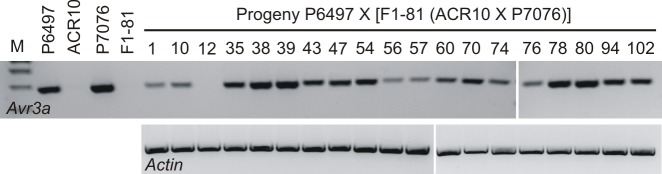

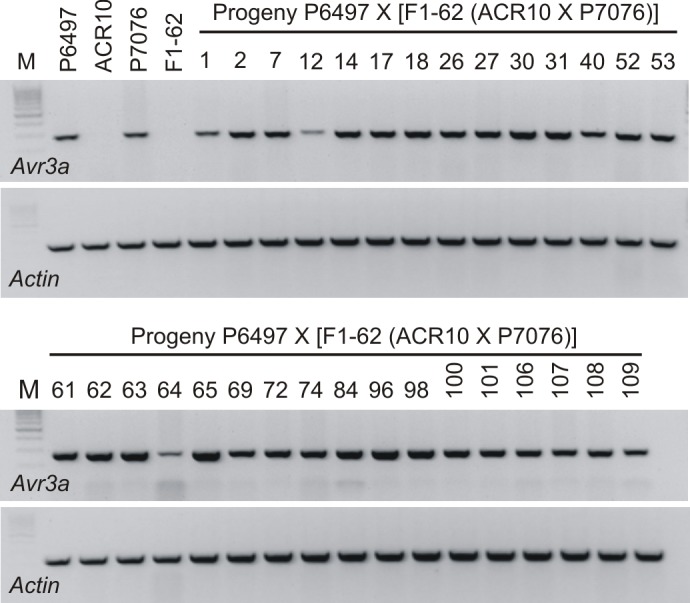

Fig 1. Analysis for Avr3a transcripts in parental P. sojae strains and progeny of test cross P6497 X [F1-62(ACR10 X P7076)].

The DNA products from RT-PCR analysis are shown after electrophoresis in agarose gels and visualization with fluorescent dye. The cDNA was synthesized using total RNA isolated from the mycelia of P. sojae. RT-PCR was carried out using gene specific primers for the P. sojae Avr3a and Actin genes. P. sojae strains are indicated above each lane; M, marker lane.

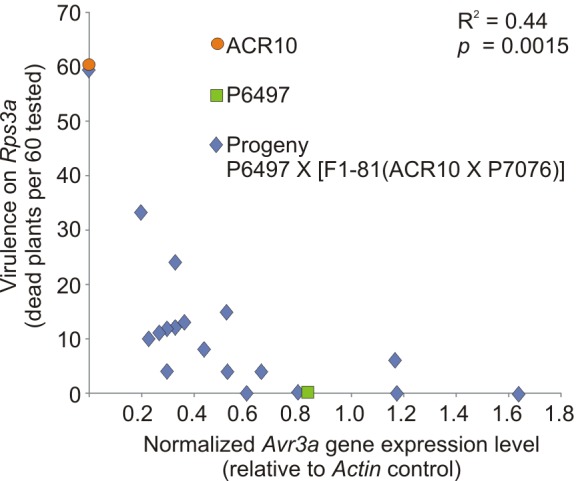

This experiment was replicated using another F1 individual. The cross of P. sojae P6497 X [F1-81(ACR10 X P7076)] was performed and a total of 19 hybrids of interest were identified; 6/19 were Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10and 13/19 were Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076. Analysis for Avr3a transcripts by RT-PCR showed that 18/19 of the hybrids possess Avr3a mRNA, whereas it is not detectable in the remaining (virulent) culture (Table 4). Among the 18 individuals with detectable Avr3a transcript, the signal intensity of Avr3a amplification product appears to be variable (Fig 2). Likewise, from the virulence assays it was found that the phenotypic penetrance of the avirulence trait in several isolates was incomplete because not all plants with Rps3a gene were killed (Table 4). To more accurately measure the Avr3a gene expression level among the cultures, quantitative real-time PCR was performed. Comparison of the results from the quantitative real-time PCR analysis and virulence tests demonstrates a correlation, with higher expression levels of Avr3a leading to greater phenotypic penetrance of the avirulence trait (Fig 3).

Table 4. Genotypes, virulence outcomes and Avr3a transcript detection in test cross progeny of P6497 X F1-81(ACR10 X P7076).

| Test cross progeny number and Avr3a genotype | Virulence on Rps3a (L83-570)1 | Virulence on rps3a (Williams)1 | Fisher’s test p-value2 | Assigned phenotype3 | Avr3a mRNA transcript (RT-PCR)4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 33 | 60 | 1.7E-10 | A’ | + |

| 10 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 24 | 60 | 6.6E-15 | A’ | + |

| 12 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 60 | 60 | 1 | V | - |

| 35 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 4 | 60 | 6.6E-30 | A | + |

| 38 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 6 | 60 | 9.4E-28 | A | + |

| 39 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 5 | 60 | 8.5E-29 | A | + |

| 43 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 12 | 60 | 1.6E-22 | A’ | + |

| 47 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 2 | 60 | 2E-32 | A | + |

| 54 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 8 | 60 | 7.7E-26 | A | + |

| 56 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 10 | 60 | 4.1E-24 | A’ | + |

| 57 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 11 | 60 | 2.7E-23 | A’ | + |

| 60 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 13 | 60 | 8.9E-22 | A’ | + |

| 70 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 3 | 60 | 4.1E-31 | A | + |

| 74 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 4 | 60 | 6.6E-30 | A | + |

| 76 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10) | 8 | 60 | 7.7E-26 | A | + |

| 78 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 0 | 60 | 1E-35 | A | + |

| 80 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 0 | 60 | 1E-35 | A | + |

| 94 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 0 | 60 | 1E-35 | A | + |

| 102 (Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076) | 9 | 60 | 5.9E-25 | A | + |

1 Number of dead plants from a total of 60 challenged, representing the sum from two independent virulence assays of 30 plants each.

2 Probability value from Fisher’s exact test, on whether the kill rate on test plants (Rps3a) differs from the kill rate on control plants (rps3a).

3 Phenotypes: A, avirulent; V, virulent; A’, incomplete avirulent.

4 Symbol (+) positive for Avr3a mRNA, (-) negative for Avr3a mRNA. All samples were positive for control Actin mRNA. Summary of results from two independent biological replicates.

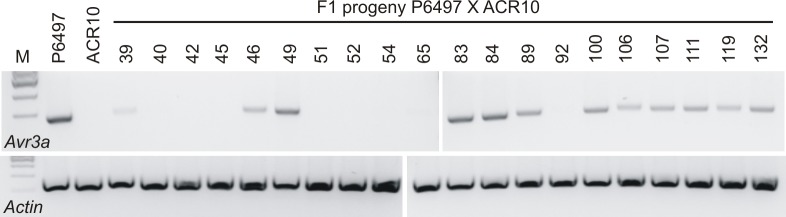

Fig 2. Analysis for Avr3a transcripts in parental P. sojae strains and progeny of test cross P6497 X [F1-81(ACR10 X P7076)].

The DNA products from RT-PCR analysis are shown after electrophoresis in agarose gels and visualization with fluorescent dye. The cDNA was synthesized using total RNA isolated from the mycelia of P. sojae. RT-PCR was carried out using gene specific primers for the P. sojae Avr3a and Actin genes. Data is missing in this analysis for Actin control of parental strains and F1-81; however, Avr3a expression results for these samples are consistent with previous analyses that included controls. P. sojae strains are indicated above each lane; M, marker lane.

Fig 3. Quantitative expression analysis of Avr3a and virulence towards Rps3a, among the progeny from test cross of P. sojae strains P6497 X [F1-81(ACR10 X P7076)].

Expression of Avr3a was determined by quantitative real-time PCR analysis. Virulence towards Rps3a was determined by a hypocotyl inoculation bioassay. Expression values are a mean, and virulence numbers are a sum of plants killed, derived from two independent biological replicates. Expression of Avr3a was normalized with P. sojae Actin. Parental P. sojae strains P6497 and ACR10 are included for comparison. The correlation (R2) and probability (p) from a regression analysis is also shown.

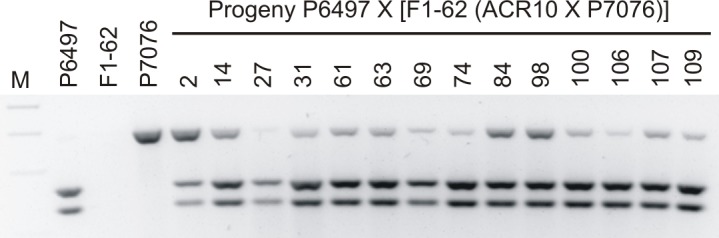

In order to determine allele specific expression of Avr3a in progeny from the test cross P6497 X [F1-62(ACR10 X P7076)], RT-PCR was performed on mRNA samples, and reaction products were digested with AluI. The Avr3aP6497allele contains a restriction site for AluI but the Avr3aP7076 allele does not [26]. In this cross, an allele-specific expression test is only feasible for progeny with the genotype Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076. It is not possible to determine whether there is allele-specific expression for progeny with the genotype Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10 since the two alleles are sequence identical. Results from this analysis show that the test cross progeny with the genotype Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076 produce transcripts of both alleles; thus the silenced Avr3a allele of P7076 was released when test crossed with P6497 (Fig 4).

Fig 4. Analysis for allele specific expression of Avr3a in P. sojae progeny from the test cross P6497 X [F1-62(ACR10 X P7076)].

The DNA products from RT-PCR analysis are shown after restriction enzyme digestion, electrophoresis and visualization with fluorescent dye. Purified mRNA transcripts from P. sojae parental strains and test cross progeny with the genotype Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076 were analyzed to determine allele specific expression. The RT-PCR was performed using Avr3a specific primers and the amplified product was digested with the restriction enzyme AluI. The Avr3aP6497allele contains a restriction site for AluI whereas the Avr3aP7076 allele does not. P. sojae strains are indicated above each lane; M, marker lane.

Cross of P. sojae strains P6497 X ACR10 results in F1 hybrids that segregate for virulence towards Rps3a

The P. sojae strains P6497 and ACR10 possess sequence identical alleles of Avr3a but differ in expression; P6497 expresses the gene whereas ACR10 does not. The results from the test crosses of P6497 X [F1 (ACR10 X P7076)] (described above) indicate that the Avr3aACR10 allele itself does not have the capability to silence the Avr3aP6497 allele, although the actual expression levels of Avr3a were variable among the progeny. To further test the interaction between the Avr3aP6497 and Avr3aACR10 alleles, we performed a direct cross between P. sojae strains P6497 X ACR10.

From a total of 220 oospores, 20 F1 hybrids were identified; the remaining 200 offspring resulted from self-fertilization of parental strains P6497 and ACR10. Results from the RT-PCR analysis of Avr3a mRNA demonstrate that the transcript is detectable in 12/20 F1 progeny whereas it is not detectable in 8/20. Plant inoculation assays show that all hybrid progeny lacking Avr3a transcripts are virulent towards Rps3a. Most progeny with detectable Avr3a transcripts are avirulent towards Rps3a but phenotypic penetrance of this trait was incomplete in some individuals, likely due to variability of expression of the Avr3a gene as estimated by the RT-PCR analysis (Fig 5, Table 5).

Fig 5. Analysis for Avr3a transcripts in parental P. sojae strains and progeny of cross P6497 X ACR10.

The DNA products from RT-PCR analysis are shown after electrophoresis in agarose gels and visualization with fluorescent dye. The cDNA was synthesized using total RNA isolated from the mycelia of P. sojae. RT-PCR was carried out using gene specific primers for the P. sojae Avr3a and Actin genes. P. sojae strains are indicated above each lane; M, marker lane.

Table 5. Parentage, virulence outcomes, and Avr3a transcript detection in F1 hybrids of P. sojae P6497 X ACR10.

| F1 progeny | Maternal parent | Virulence on Rps3a (L83-570)1 | Virulence on rps3a (Williams)1 | Fisher’s test p-value2 | Assigned phenotype3 | Avr3a mRNA transcript (RT-PCR)4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 39 | P6497 | 59 | 60 | 0.5 | V | + |

| 40 | ACR10 | 60 | 60 | 1 | V | - |

| 42 | ACR10 | 60 | 60 | 1 | V | - |

| 45 | P6497 | 56 | 60 | 0.05936 | V | - |

| 46 | P6497 | 4 | 60 | 6.6E-30 | A | + |

| 49 | P6497 | 18 | 53 | 2.8E-11 | A’ | + |

| 51 | ACR10 | 59 | 60 | 0.5 | V | - |

| 52 | ACR10 | 54 | 56 | 0.21033 | V | - |

| 54 | ACR10 | 45 | 60 | 1.1E-05 | V’ | - |

| 65 | P6497 | 60 | 60 | 1 | V | - |

| 83 | ACR10 | 17 | 60 | 5.1E-19 | A’ | + |

| 84 | P6497 | 0 | 60 | 1E-35 | A | + |

| 89 | ACR10 | 12 | 60 | 1.6E-22 | A’ | + |

| 92 | P6497 | 60 | 60 | 1 | V | - |

| 100 | P6497 | 39 | 60 | 5.7E-08 | A’ | + |

| 106 | P6497 | 0 | 60 | 1E-35 | A | + |

| 107 | P6497 | 2 | 60 | 2E-32 | A | + |

| 111 | ACR10 | 7 | 60 | 9E-27 | A | + |

| 119 | P6497 | 0 | 60 | 1E-35 | A | + |

| 132 | ACR10 | 5 | 60 | 8.5E-29 | A | + |

1 Number of dead plants from a total of 60 challenged, representing the sum from two independent virulence assays of 30 plants each.

2 Probability value from Fisher’s exact test, on whether the kill rate on test plants (Rps3a) differs from the kill rate on control plants (rps3a).

3 Phenotypes: A, avirulent; V, virulent; A’, incomplete avirulent; V’, incomplete virulent.

4 Symbol (+) positive for Avr3a mRNA, (-) negative for Avr3a mRNA. All samples were positive for control Actin mRNA. Summary of results from two independent biological replicates.

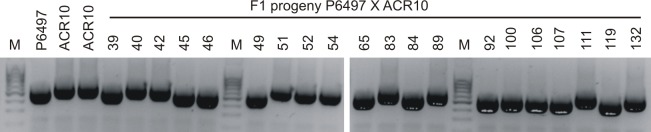

Maternal or paternal effects do not determine gene silencing of Avr3a in F1 progeny from P6497 X ACR10

The apparent 1:1 segregation of Avr3a expression in the F1 hybrids from P6497 X ACR10 suggests a parental effect, such as imprinting or heterozygosity, might be influencing the outcome. Therefore we identified the maternal parent of hybrids using a mitochondrial DNA marker (Fig 6, Table 5). For the 20 F1 progeny from the P6497 X ACR10 cross, results show that P6497 is the maternal parent for 11/20, and of these, 8/11 are positive for Avr3a expression. The ACR10 strain is the maternal parent for 9/20, and of these, 4/9 are positive for Avr3a expression. Therefore, the results do not correlate and there are no apparent maternal or paternal effects on Avr3a gene silencing for progeny from this cross.

Fig 6. Mitochondrial DNA marker analyses of parental strains and F1 hybrids from a cross of P. sojae strains P6497 X ACR10.

The DNA products from PCR analysis are shown after electrophoresis in agarose gels and visualization with fluorescent dye. Shown are PCR amplified products of a mitochondrial DNA fragment from P. sojae strains P6497 and ACR10, and their F1 progeny; M, marker lane.

Parental heterozygosity at a locus controlling Avr3a expression or silencing is another possible explanation for 1:1 segregation ratios in F1 progeny. To determine whether potential heterozygosity within the parental strains P6497 and ACR10 could account for the variation in virulence and Avr3a gene expression in the F1 progeny, a total of 50 self-fertilized oospores were isolated from each of the strains. Out of total 50 progeny developed by self-fertilization of strain ACR10, all (50/50) lack detectable Avr3a transcripts by RT-PCR analysis. Most of the progeny (45/50) are virulent towards test (Rps3a) and control (rps3a) plants, but some (5/50) are intermediate in virulence towards test (Rps3a) and/or control (rps3a) soybean plants (S1 Table). All of the self-fertilized progeny (50/50) developed by P6497 X P6497 are avirulent towards soybean Rps3a and possess detectable Avr3a transcripts (S2 Table). Results indicate that the apparent 1:1 segregation of Avr3a expression in the P6497 X ACR10 progeny is unlikely to be due to parental heterozygosity, since each of the parental strains were true breeding for Avr3a expression.

Segregation of virulence towards Rps3a, and Avr3a expression in F2 progeny from P6497 X ACR10

To study the segregation pattern of the Avr3a virulence trait and gene expression in F2 progeny from the cross P6497 X ACR10, independent F2 populations were created by self-fertilization of six different F1 individuals. Three F2 populations were from virulent F1s lacking Avr3a mRNA transcripts, and three were from avirulent F1s that express the Avr3a gene. A total of 150 F2 progeny were isolated, including 75 for each of the two classes of F1s. Results show that all 75 F2 individuals arising from self-fertilization of virulent F1s lacking Avr3a transcripts were virulent towards soybean carrying Rps3a gene, and do not possess Avr3a mRNA transcripts (Table 6). By contrast, the F2 populations from avirulent F1 progeny segregate for Avr3a expression and virulence towards Rps3a. The segregation of virulent:avirulent phenotypes matches a 1:3 ratio, by chi-squared analysis.

Table 6. Segregation analysis for F2 populations developed from virulent and avirulent F1 hybrids of P6497 X ACR10.

| Phenotype1 | F1 | F2 | F2 Phenotype2 | p-value3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population n | Avirulent mRNA(+) n | Virulent mRNA(-) n | |||

| F1 hybrids silenced for Avr3a and virulent towards Rps3a | |||||

| F1-51 | 25 | 0 | 25 | - | |

| F1-52 | 25 | 0 | 25 | - | |

| F1-92 | 25 | 0 | 25 | - | |

| Total | 75 | 0 | 75 | - | |

| F1 hybrids expressing Avr3a and avirulent towards Rps3a | |||||

| F1-46 | 25 | 19 | 6 | 0.91 | |

| F1-111 | 25 | 21 | 4 | 0.30 | |

| F1-119 | 25 | 16 | 9 | 0.20 | |

| Total | 75 | 56 | 19 | 0.95 | |

1 Selected F1 hybrids from P6497 X ACR10

2 Virulence towards Rps3a and presence of Avr3a mRNA. F2 progeny with avirulent phenotype were positive for Avr3a mRNA transcript (+) and progeny with virulent phenotype were negative for Avr3a mRNA transcript (-), without exception, as determined by RT-PCR.

3 p-value from χ2 analysis for 3:1 segregation

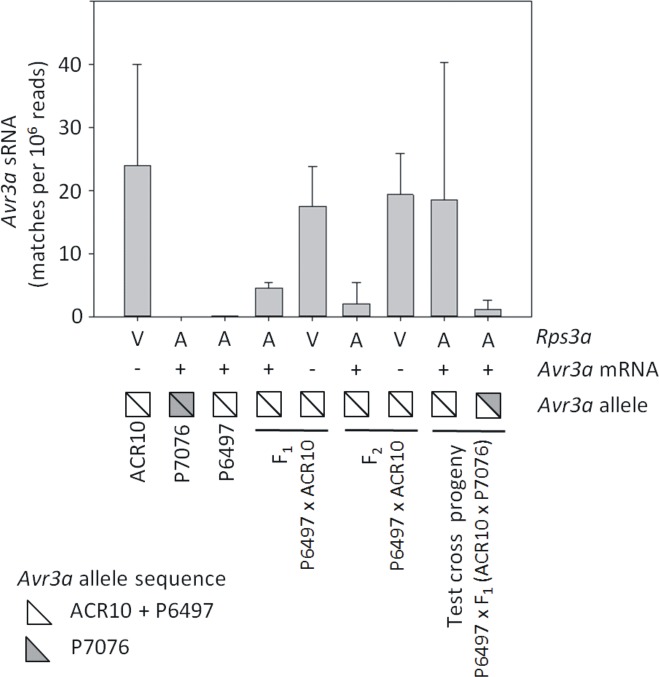

The presence of Avr3a small RNA molecules is usually associated with silencing in parental strains and progeny

We previously showed that Avr3a sRNA of 25 nt in length are abundant in the gene silenced strain ACR10 but not in the expressing strain P7076. All progeny from the cross ACR10 X P7076 were gene silenced for Avr3a and possessed abundant sRNA, regardless of genotype [30]. To measure the levels of Avr3a sRNAs progeny from the test cross P6497 X [F1(ACR10 X P7076)] and from the direct cross P6497 X ACR10, we performed deep sequencing and counted sRNA matching to Avr3a. Nine different P. sojae strains or hybrids were tested and three biological replicates were performed for each (with one exception, data is available for only two replicates of parental strain P7076), for a total of 26 samples. The results are summarized in Fig 7 and S3 Table. The results indicate that Avr3a gene silenced strains or hybrids always possess abundant Avr3a sRNA (values ranging from 10 to 42 matches per 106 reads). Gene expressing strains or hybrids usually possessed far less Avr3a sRNA, but this result was not consistent among the hybrid progeny. Parental strains expressing Avr3a (P7076 and P6497) had the lowest levels of Avr3a sRNA (values ranging from 0 to 0.13 matches per 106 reads). Hybrid progeny expressing Avr3a often had higher amounts of Avr3a sRNA than parental strains with the same phenotype. In fact, the highest amount of Avr3a sRNA that we measured (43 matches per 106 reads) was from a test cross progeny that phenotypically expresses Avr3a and is avirulent to Rps3a. However, this was an exception, and all of the other hybrid progeny expressing the gene possessed lower levels of sRNA (values ranging from 0 to 6.3 matches per 106 reads). Overall, the results suggest that Avr3a sRNA is necessary but not sufficient for gene silencing.

Fig 7. Prevalence of small RNA to Avr3a in parental strains and hybrids of P. sojae.

Shown are the mean and range of values for matches of sRNA to Avr3a, as determined by deep sequencing of sRNA libraries. Values are from three independent biological replicates, with the exception of strain P7076 for which there were two replicates. Below the graph is shown the virulence of to Rps3a (V, virulent; A, avirulent); the presence (+) or absence (-) of Avr3a mRNA transcripts as determined by RT-PCR; the DNA sequence genotype at the Avr3a locus; and the P. sojae strain or progeny identification. P. sojae strains P6497 and ACR10 possess sequence identical alleles of Avr3a but differ in expression.

Discussion

Recent research has indicated that the variation of Avr3a mRNA transcript levels determines the virulence of P. sojae towards soybean plants carrying the resistance gene Rps3a. Strains that possess Avr3a mRNA transcripts are avirulent but strains lacking Avr3a mRNA transcripts are virulent towards soybean plants carrying Rps3a [20,26]. It has also been found that crosses between P. sojae strains P7076 (avirulent phenotype; Avr3aP7076/ Avr3aP7076) X ACR10 (virulent phenotype; Avr3aACR10/ Avr3aACR10) causes transgenerational gene silencing of Avr3a and gain of virulence in all F1 and F2 progeny, despite normal segregation of the Avr3a gene itself [30]. Our results now demonstrate that gene silencing of Avr3a is meiotically stable in progeny from P. sojae strains P7076 X ACR10 to the F5 generation. No Avr3a mRNA transcripts were detected in any of the progeny. The virulence assay results indicate that all the progeny retained virulence towards soybean cultivars carrying the Rps3a gene, with the exception of one outlier isolate in each of F4 and F5 progeny that suffers from a general loss of pathogenicity. The loss of pathogenicity, indicated by a loss of virulence towards control plants lacking any known Rps genes, was also observed at low frequency among the self-fertilized ACR10 progeny. We cannot account for the spontaneous loss of pathogenicity of these cultures, but it is a phenomenon that has long been known to occur in P. sojae [18,33].

The stability of Avr3a silencing was tested because it is known from other examples of transgenerational or inherited epigenetic phenomena that gene silencing can fade over generations or be influenced by environmental effects [34–37]. This could occur if an epigenetic factor required for silencing is not fully self-propagating or is (de)activated by an environmental condition. Meiosis is also a process that can re-set epigenetic control, especially for developmental or environmentally induced epigenetic changes that occur during somatic cell division [38,39]. Results from our experiments demonstrate that Avr3a gene silencing in progeny from P. sojae ACR10 X P7076 is stable through F4 and F5 progeny. Additionally, since the original cross was made well before the current experiments were conducted, the results show that Avr3a silencing is temporally stable over at least five years. Thus, if an inherited epigenetic factor is responsible for Avr3a silencing in this cross, then this factor is exceptionally stable under the experimental conditions tested here.

Another reason to test stability of Avr3a gene silencing was to determine whether Avr3a expression could be reconstituted in F4 or F5 progeny. If transgenerational effects are simply the result of a multiple independent loci segregating in the cross, that are necessary for Avr3a expression but that are not recovered in the proper combination in the F2 progeny, then reconstitution of Avr3a expression could occur in further generations. In simple epistatic silencing events, one would expect to find recombination and segregation in F2 populations, and reconstitution of transcription of the Avr3a gene within some or many of the F2 progeny. This was not observed. Results show that reconstitution of Avr3a expression did not occur in any of the F4 or F5 progeny, so it is not possible to conclude with certainty whether multiple epistatic loci are required. Nonetheless, a parsimonious interpretation of the outcome tends to discount the multiple-epistasis hypothesis. The scenario that P. sojae strain ACR10 is lacking multiple independent factors, each required in a homozygous condition specifically for Avr3a gene expression, in a combination that was never recovered in any of the progeny, is possible but implausible.

Other hypotheses invoking epistatic loci to account for the silencing of Avr3a in progeny from P. sojae ACR10 X P7076 are possible, such as chromosomal changes, high frequency gene conversion, or loss of heterozygosity. These phenomena can occur in hybrid cultures generated from crossing different strains, and have been demonstrated to varying degrees in a number of oomycete species including P. sojae, P. infestans, P. parasitica, P. cinnamomi and Pythium ultimum, [9,14,40–42]. For example, if P. sojae strains ACR10 and P7076 differ at an epistatic locus that is necessary for Avr3a gene expression or silencing, then gene conversion, loss of heterozygosity or chromosomal changes affecting the epistatic locus in hybrid cultures could cause unusual inheritance patterns. However, this scenario requires special assumptions. First, the hypothetical epistatic factor must exclusively convert to the haplotype which results in Avr3a silencing. Second, this change must occur instantaneously in all hybrid progeny. Although there are only a limited number of studies of gene conversion and loss of heterozygosity in P. sojae, the results tend to contrast with the observations of Avr3a inheritance in the ACR10 X P7076 cross. Loss of heterozygosity may show strong allele-specific bias but it is unusual for all hybrid progeny to exclusively convert to one allele [9]. Models and previous observations also suggest that loss of heterozygosity is time dependent, and tends to accumulate in hybrid cultures as they are clonally propagated, rather than occurring instantaneously [9]. Therefore, the characteristics of Avr3a gene silencing in hybrid progeny differ from the known examples of loss of heterozygosity in P. sojae, but it is not possible to discount this hypothesis as an explanation.

One of the goals of this study was to determine whether the silenced alleles of Avr3a have an ability to silence the expressed alleles of other P. sojae strains, as was previously shown in the cross of P. sojae strains ACR10 X P7076. The outcome from the test cross of P6497 X [F1(ACR10 X P7076)] demonstrates that all progeny with the genotype Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076 or Avr3aP6497/ Avr3aACR10 express Avr3a mRNA transcripts. For the progeny with the genotype Avr3aP6497/Avr3aP7076, expression of both alleles was detected, and thus the silencing of the Avr3aP7076 allele was released by out-crossing. For the progeny with the genotype Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10, it was not possible to determine allele specific expression, but it is clear that the Avr3aACR10 allele does not have the capability to silence the Avr3aP6497 allele in this circumstance. The results differ from classical examples of paramutation, which is a phenomenon of gene-silencing where a paramutagenic allele has the ability to silence the paramutable allele, and paramutable alleles gain the ability to be paramutagenic [43]. However, the known examples of paramutation are diverse in their characteristics, so it remains possible that paramutation and gene silencing of Avr3a share underlying mechanistic features.

In the second replicate of the test cross, the phenotypic penetrance of the Avr3a avirulence trait was found to be incomplete in many of the progeny. We observed plants with the Rps3a gene being killed by inoculation with the progenies from the test cross, despite that expression of Avr3a was detected in these cultures. Furthermore, the Avr3a transcript level varied among the progeny and correlated well with the virulence profiles of the isolates. The results indicate that expression of the Avr3a gene is not fully restored in all of the progeny, and demonstrate a quantitative effect of Avr3a expression and avirulence towards the Rps3a resistance gene.

It is not known what causes the variation of Avr3a transcript levels in the test cross progeny, but the results clearly show that silencing is released by out-crossing and that transgenerational inheritance does not occur. A possible explanation for this outcome is involvement of strain specific factors in Avr3a gene expression and/or silencing. As previously discussed, a hypothetical epistatic factor necessary for Avr3a expression or silencing can be invoked to explain the unusual inheritance patterns in progeny from the ACR10 X P7076 cross, if one assumes all the special conditions are met. Likewise, the release of gene silencing in the test cross hybrids could be due to the presence of strain specific factors in P. sojae P6497 that regulate expression of Avr3a or that control epigenetic inheritance.

The results from the P6497 X ACR10 cross show both differences and similarities to the results from the test cross of P6497 X [F1(ACR10 X P7076)]. The test cross results were different because all 23 progeny with the heterozygous genotype Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10 were avirulent towards soybean Rps3a and expressed Avr3a transcripts, whereas these traits segregated in F1 from the direct cross of P6497 X ACR10 that had the identical heterozygous genotype Avr3aP6497/Avr3aACR10. Nonetheless, for the F1 progeny that produced detectable Avr3a mRNA, from either cross, the expression level appeared to be variable, and this influenced the phenotypic penetrance of the avirulence trait.

The apparent 1:1 segregation of Avr3a expression in the F1s from P6497 X ACR10 could not be explained by parent-of-origin effects or by heterozygosity of the parental strains. To further study the inheritance of Avr3a expression in progeny from the P6497 X ACR10 outcross, we developed F2 populations from virulent and avirulent F1 hybrids. The F2 populations developed from virulent F1 individuals were all virulent and silenced for Avr3a expression, whereas these traits segregated in F2s derived from avirulent F1 individuals. The overall segregation ratio of Avr3a expressing: Avr3a silenced F2 progeny was 56:19, which fits a 3:1 ratio. These results suggest that Avr3a expression is inherited as a simple dominant trait in the F2 progeny that develop from F1 hybrids expressing Avr3a.

A possible explanation to account for the results from the P6497 X ACR10 cross is that there is a factor necessary for the expression of Avr3a present in P. sojae strain P6497 but not in ACR10, such as a factor that suppresses the silencing of Avr3a. In half the F1 hybrid progeny, this factor is somehow lost, resulting in the presence of Avr3a-silenced F1 individuals that are true breeding. In F1 progeny that express Avr3a transcripts, the factor remains in an apparent heterozygous state, so that the F2 progeny segregate in a 3:1 ratio for Avr3a expression.

Although there clearly must be multiple factors that are necessary for Avr3a expression or silencing, invoking gene conversion or loss of heterozygosity of these factors to account for the inheritance of Avr3a expression is troublesome because special conditions must be assumed to fully explain the results. There is also evidence from other studies indicating that loss of heterozygosity cannot account for changes in Avr gene expression states in P. sojae. For example, the P. sojae Avr1a and Avr1c genes show apparent epiallelic variation in expression [22]. Sequence identical alleles of each, Avr1a and Avr1c, can produce mRNA transcripts or be silenced, in a strain-specific manner. The inheritance of gene silencing has not been studied for Avr1a or Avr1c, but it is known that clonally propagated strains can spontaneously switch expression states for each of these genes [20,22]. Loss of heterozygosity is not likely to underlie the Avr1a or Avr1c gene expression states in these studies because no hybridization events were involved. It has also been demonstrated that virulence towards Rps1a can be repeatedly lost and recovered in successive single zoospore isolates of P. sojae [44].These observations cannot be explained by gene conversion or loss of heterozygosity, which are irreversible processes [9].

The relationship between gene silencing of Avr3a and the presence of corresponding sRNA molecules was investigated by deep sequencing. Our interpretation of the results is that Avr3a sRNA are necessary but not sufficient for silencing of the gene. In other organisms where gene silencing mechanisms have been deeply investigated, models indicate that sRNAs must form a complex with protein effectors in order for silencing to be accomplished, whether it is transcriptional or post-transcriptional. Thus, sRNA does not act independently to achieve silencing. One possibility to account for our results is that there is strain specific variation in P. sojae for components of the silencing complex that enable the uncoupling of sRNA from the Avr3a gene silenced phenotype.

The results presented here cannot be easily explained but they do indicate that there is strain-specific interplay between conventional and epigenetic variations in P. sojae. Support for this conclusion is provided by comparative genomic studies of Phytophthora infestans and its sister species demonstrating that epigenetic regulators, such as genes predicted to encode histone methyltransferases, can be highly polymorphic and show signs of positive selection [45]. The modulation of gene expression states by heterochromatin based mechanisms, and by sRNA or transposon sequences, has also been described or proposed to occur in P. infestans [46–50]. Our results discount a role for parental imprinting of Avr3a and help to provide a path forward for discovery of the additional factors that regulate the expression of this gene.

Materials and Methods

Phytophthora sojae strains

Cultures of P. sojae parental strains P6497, ACR10, and P7076 were from our collection, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, London, ON. No specific permission was required for research on this organism. The origin of the parental strains used in this study has been described [15,20]. Progeny from the cross of ACR10 X P7076 have previously been described [30]. For short term (up to one year) storage, cultures were maintained on 2.5% (v/v) vegetable juice (V8) agar medium at 16°C in the dark. For prolonged storage, parental strains and hybrid progeny were cryo-preserved in liquid nitrogen.

Plant materials

Soybean (Glycine max) cultivar Williams (rps) and the corresponding isoline L83-570 (Rps3a) were grown in field plots at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, London, ON. No specific permission was required for this location or activity. The experiments did not involve the use of transgenic plants. The field use did not involve endangered or protected species. The seeds were harvested and used for virulence assays, as described below.

Culture and cross of P. sojae

Phytophthora sojae strains were cultured by transferring 5 mm diameter mycelial plugs cut from the growing edge of a culture onto 26% (v/v) vegetable juice (V8) agar (regular) medium and incubated at 25°C for 7 d in the dark. Crossing media plates [2.5% (v/v) V8 juice agar] supplemented with β-sistosterol (10μg/mL), kanamycin (50 μg/mL), ampicillin (100 μg/mL), and rifampicin (10 μg/mL) were freshly prepared. To cross two different strains or to perform self-fertilization of P. sojae, fresh culture from a growing edge of regular V8 juice medium (5 mm square) was transferred aseptically on the centre of the crossing plate and incubated at 25°C for 7 d in darkness. After incubation, cultures grown on separate plates were homogenized together and co-cultivated on crossing medium plates at 25°C in darkness for 5 weeks. Cultures were homogenized using a 10 mL sterile syringe with 18-gauge needle. Darkness was maintained using aluminium foil to wrap the plates.

Generation of F4 and F5 progeny from P. sojae cross ACR10 X P7076

Selected F3 progeny with the genotype Avr3aP7076/Avr3aP7076 were available from the cross ACR10 X P7076. These cultures were self-fertilized to produce F4 and F5 progeny. The original ACR10 X P7076 cross was previously performed and the progeny were maintained in the laboratory [30]. A total of four F3 individuals (F3-40, F3-60, F3-83, and F3-87) were revived from cryo-storage, and self-fertilized to generate F4 progeny; similarly, F5 progeny were developed from the F4 progeny.

Isolation of oospores

All the steps for isolation of oospores were performed aseptically at a laminar flow bench. Out-crossing or self-fertilization was performed as described above. After maturation, oospores were isolated by maceration, filtration, centrifugation, and other purification steps, as previously outlined [16] and described below. After incubation for 5 weeks, four plates (for each crossing) of matured cultures were sliced using a sterile blade. Using a pre-chilled commercial blender (Waring), the diced material from all four plates was homogenized with 100 mL of 4°C sterile water. Two pulses of one min each were performed, so as not to overheat the sample.

The cultures were then sieved through three sterile 75 μm nylon membrane to remove agar and mycelium. The filtrate was collected into a 50 mL sterile conical tube and frozen at -20°C for 24 hours to kill the hyphae. In the following day, the culture was thawed at 45°C water bath for 10 minutes and re-filtered using three sterile 75 μm nylon membranes. The filtrate was collected into a 50 mL sterile conical tube and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes. Mycelial fragments and agar which floated on the supernatant were removed using a sterile Pasteur pipette. A darkly coloured pellet of oospores can be observed after centrifugation. This pellet was then washed three times with sterile water.

The pellet containing oospores was treated with β-glucuronidase (2000 units/mL suspension) and incubated at 37°C for 16 h. After incubation, the oospore suspension was centrifuged and washed three times and re-suspended into 20 mL of sterile distilled water. Kanamycin (50 μg/mL) and ampicillin (100 μg/mL) were added to the suspension and oospores were spread on 1.5% (w/v) water agar plates supplemented with 10 μg/mL β-sistosterol and rifampicin (10 μg/mL), approximately 500 oospores per plate (90 x 16 mm). The oospores on the water agar plates were incubated at 25°C in the dark. Oospores begin to germinate after 2–4 days. Plates were checked every other day using a stereomicroscope (60X magnification). Germinating oospores were transferred from the water agar plate to regular V8 juice media using a sterile diamond-head transfer needle and incubated at 25°C for 7 days in the dark. The cultures grown from pure isolated oospores were then used for further DNA and RNA work.

Genomic DNA isolation

Genomic DNA was extracted from mycelial cultures of P. sojae strains using standard phenol chloroform extraction followed by isopropanol precipitation. Cultures of P. sojae arising from single oospores were transferred to regular V8 medium and incubated at 25°C for 7 days. A lawn of P. sojae mycelia growing on the surface of the V8 juice medium was collected by scraping with a sterile pipette tip (blunt end). The mycelia was then transferred into a 2 mL Eppendorf tube containing 1 mL mycelial extraction buffer and frozen at -20°C for 24 hours. The mycelia extraction buffer contained: 200 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.5), 250 mM NaCl, 25 mM EDTA, 2% SDS, and sterile water. The next day, the frozen sample was thawed at room temperature. Phenol (750 μL) was added, and the sample was vortexed and centrifuged (13,000 rpm for 15 minutes). The supernatant containing the DNA was collected and re-extracted again with phenol. The aqueous suspension was collected, and phenol: chloroform (1:1) was added, and the sample was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min. A solution (500 μL) of chloroform: isoamyl alcohol (24:1) was; added to the supernatant, and the sample was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was collected and RNA was removed by adding RNase A (1.5 μL of 10 mg/ml). Isopropanol (60% volume of total DNA suspension) was added to the DNA suspension and the sample was kept at -20°C overnight to precipitate the DNA. The DNA pellet was obtained by centrifugation (13,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C). The DNA pellet was then washed with 70% (v/v) ethanol, centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 5 min, and air dried (10 minutes). The dried pellet was dissolved in a solution of 10 mM Tris HCl and 0.1 mM EDTA, heated at 65°C for 10 min and stored at -20°C.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

For all PCR amplifications, a three step PCR method was applied. Initial denaturation temperature of the PCR reaction was 94°C for 2 min. The three step cycle was: denaturation (94°C for 40 sec), annealing (annealing temperature was according to primers used for 40 sec), and extension (72°C for 1 min). After completion of all cycles, a 72°C extension temperature was applied for 10 min. The number of PCR cycles varied according to the purpose of the experiment; for restriction digestion, 40 cycles were used, for RT-PCR, 30 cycles were used. The PCR amplification was performed using 15 ng genomic DNA as template. The PCR mixture (25 μL) was prepared using following reaction components: 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μM of each forward and reverse primers, 1.25 U Taq DNA polymerase and 1X PCR buffer as recommended by the supplier (Invitrogen, Life Technologies). Gel electrophoresis was performed to resolve products, which were visualized using a fluorescent dye (SYBR safe, Invitrogen).

Hybrid determination

To determine the hybrid progeny (P6497/ACR10 or P6497/P7076) from crosses of P6497 X F1 (ACR10 X P7076), two different co-dominant cleaved amplified polymorphisms (CAPs) markers were analysed. The Scaf-29-M2 sequence (448 bp) with strain-specific sequence polymorphisms was amplified using forward primer (5'-CCCTCGAGAACGCCAACTT-3') and reverse primer (5'-CCTCGCTCGCCTTCATCC-3'). A list of all primer sequences is provided in (S4 Table). The Scaf-29-M2 sequences of strain ACR10 and P7076 possess a restriction site for the enzyme EcoRV but strain P6497 does not. Similarly, Avh320 sequence (400 bp) was amplified using forward primer (5'-AACGCTCTCGAAAGTGGC-3') and reverse primer (5'-AAAGAACTTCGACAG CC-3'). The Avh320 sequences of strains P6497 and ACR10 have a restriction site for ClaI but strain P7076 does not. To track segregation of the Avr3aP6497 and Avr3aP7076 or Avr3aACR10 alleles, forward primer (5'-GCTGCTTCCTTCCTGGTTGC-3') and reverse primer (5'-GCTGCTGCCTT TTGCTTCTC-3') were used and amplified Avr3a sequences were digested with restriction enzyme AluI. The Avr3a sequences of ACR10 and P6497 include a restriction site for AluI but the Avr3a sequence of P7076 does not.

Restriction Digestion

To analyse the CAPs markers, PCR amplification was performed as described above using 15 ng genomic DNA as template. For restriction digestion of amplified sequences, 10 μL volumes of amplified products and 10 μL enzyme mixtures (3 U of respective enzyme, buffer and BSA (New England Bio labs) were mixed and incubated according to the optimum temperature of the restriction enzymes. Gel electrophoresis was performed to resolve products, which were visualized using fluorescent stain (SYBR safe, Invitrogen).

Extraction of RNA and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

To study the expression of the Avr3a gene of P. sojae strains, total RNA was extracted from mycelial tissues. Phytophthora sojae isolates were cultured on cellophane (Ultra Clear Cellophane, RPI Crop) placed over 26% (v/v) V8 juice agar medium, and incubated at 25°C for 7 d in darkness. The cellophane disks containing mycelia were then peeled off the agar medium, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until used. Mycelial tissues were ground in liquid nitrogen to a fine powder. Total RNA was extracted using a solution of phenol-guanidine isothiocyanate (Trizol) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer (Invitrogen). The steps applied to extract RNA were as follows. In each conical tube containing equal mass of frozen, powdered mycelial tissue, Trizol reagent (4 mL) was added and sample was mixed. The suspension was dispensed into 2 ml Eppendorf tubes and 700 μL chloroform was added. The sample was vortexed, and kept at room temperature for 3 minutes. Tubes were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm at 4°C and the supernatant was collected into 15 mL conical tubes. The supernatant was transferred into 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes and equal volume of isopropanol was added in each tube. The samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded and pellet was washed with 1 ml 75% ethanol prepared in DEPC treated water, then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 3 minutes at 4°C. The RNA pellet in the tube was air dried and dissolved in DEPC treated water and stored at -80°C. Total RNA samples were quantified using a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Thermo Scientific, USA) and their integrity was checked by electrophoretic analysis of 200 ng of each sample on 1% (w/v) agarose gel in 1X TAE buffer (40 mM Tris, 40 mM acetate, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.2–8.4). For RT-PCR, 1 μg of total RNA was treated with DNase I and first-strand cDNA was synthesized using reverse transcriptase (Superscript III, Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer's directions. The Avr3a mRNA transcript was detected by PCR with the forward primer (5'-GCTGCTTCC TTCCTGGTT GC-3') and the reverse primer (5'-GCTGCTGCCTTTTGCTTCTC-3'). List of primers used in this project is given in table 2.2. Primers-specific for P. sojae Actin were used as a control. A minimum of two independent biological replicates, prepared separately and at different times, were performed for each analysis.

Virulence assay

The standard hypocotyl inoculation based assay was employed to test the virulence of P. sojae cultures [51]. The soybean cultivars Williams (rps) and Williams isoline L83-570 (Rps3a) were used. Seeds were sown in 10 cm pots (~15 seeds per pot). Soybean plants were grown for 7 days in a growth chamber which was maintained with 16 h continuous light supply, 25°C day temperature followed by 16°C night temperatures before inoculations. Phytophthora sojae cultures were grown on 0.9% (w/v) V8 juice agar medium for 7 d, and macerated using 10 mL syringe with 18-gauge needle. The mycelial slurry (approximately 300 μL) was inoculated in the hypocotyl of soybean plant by making an incision below the epidermal layer. Plants were covered with plastic bags for 3 d, and then left for another 3 d without bags and the disease outcome was scored on day 6.

Identification of maternal parent in P. sojae cross P6497 X ACR10

To identify the maternal parent of F1 hybrids from the cross P6497 X ACR10, a mitochondrial DNA marker was developed to track the inheritance of this organelle. Polymorphisms in the mitochondrial DNA sequence were identified by comparison of the reference genome P6497 to the re-sequenced strain ACR10, and verified by PCR amplification and Sanger DNA sequencing [52,53]. Specifically, primers were designed to flank an insertion/deletion polymorphism of 96 bp, present in ACR10 but absent from P6497. The PCR reaction was performed using total genomic DNA as template and mitochondrial DNA sequence specific primers (forward primer 5'-TTTGGTGTATAGTTTCCCAACC-3', and reverse primer 5'-CGTGTTACTCACCCGTTCG-3'). The amplicon was then visualized by gel electrophoresis using 2% agarose gel. Maternal parentage of progeny was determined by comparing the size of the amplified product to that of control samples from P. sojae strains P6497 and ACR10.

Quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR) to study the expression level of Avr3a gene among P. sojae hybrids

To quantitatively measure the expression of Avr3a in selected P. sojae cultures, quantitative real time PCR was performed. To perform quantitative real time PCR, labelled nucleotides (Cyber-Green SuperMix, Quanta Biosciences) were used with real time detection system (CFX96, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., USA). The cDNA was prepared from RNA samples and purified as described above, using reverse transcriptase (Superscript III, Invitrogen). The Avr3a gene expression was analysed using gene specific primers (forward primer: 5’-TCGCTCAAGTTGTGG TCGTC-3’ and reverse primer: 5’-TCGACAGCGTCCTATCTTCG-3’). The primers used for reference gene (Actin) amplification were forward primer: 5’-CGAAATTGT GCGCG ACATCAAG-3’ and reverse primer: 5’-GGTACCGCCC GACAGCACGAT-3’. The data were analyzed using software (CFX manager, Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., USA).

Small RNA sequence analysis

Total RNA was extracted from mycelia cultures of P. sojae as described above. Construction of small RNA libraries using the Illumina TruSeq small RNA kit and sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq2000 followed instructions provided by the manufacturer. Single reads of 50 nt in length were obtained. Sequences were trimmed by Scythe (https://github.com/vsbuffalo/scythe) and filtered based on Q30 scores. Any sequences less than 21 nt or that Scythe could not trim were discarded. The remaining sequences were compared to a 556 bp target sequence comprised of the Avr3a open reading frame (336 bp) and 100 bp of flanking sequence from the adjacent 3’ and 5’ regions, and matching sequences were counted. The number of matches was normalized to the total number of trimmed and filtered sequences for each library. This analysis was performed using Avr3a allele sequences from the reference genome strain P6497 and from strain P7076, to determine whether the target allele sequence influenced the number of sRNA matches. The results did not differ substantially between the two analyses.

Data deposition

Small RNA sequence data for all samples described in this study is available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive, Bioproject PRJNA300858.

Supporting Information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We thank The Centre for Applied Genomics (Sick Kids Hospital, Toronto) and the McGill University/Genome Quebec Innovation Centre (Montreal) for small RNA sequencing; R. Greg Thorn, Richard Gardiner and Vojislava Grbic (University of Western Ontario) for advice and comments during the course of this study; and our laboratory colleagues Kuflom Kuflu, Chelsea Ishmael, and Ren Na for their help and support.

Data Availability

Small RNA sequence data for all samples described in this study are available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive, Bioproject PRJNA300858.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by Government of Canada, Department of Agriculture and Agri-Food, Genomics Research and Development Initiative, J-00044. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Erwin DC, Ribeiro OK (1996) Phytophthora Diseases Worldwide. St. Paul, MN: The American Phytopathological Society. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kroon LP, Brouwer H, de Cock AW, Govers F (2012) The genus phytophthora anno 2012. Phytopathology 102: 348–364. 10.1094/PHYTO-01-11-0025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tyler BM, Gijzen M (2014) The Phytophthora sojae genome sequence: Foundatoin for a revolution In: Dean RA, Lichens-Park A, Kole C, editors. Genomics of Plant-Associated Fungi and Oomycetes: Dicot Pathogens. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamoun S, Furzer O, Jones JD, Judelson HS, Ali GS, et al. (2015) The Top 10 oomycete pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol Plant Pathol 16: 413–434. 10.1111/mpp.12190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Layton AC, Kuhn DN (1988) The virulence of interracial heterokaryons of Phytophthora megasperma f.sp. glycinea. Phytopathology 78: 961–966. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whisson SC, Drenth A, Maclean DJ, Irwin JA (1994) Evidence for outcrossing in Phytophthora sojae and linkage of a DNA marker to two avirulence genes. Curr Genet 27: 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.May KJ, Whisson SC, Zwart RS, Searle IR, Irwin JA, et al. (2002) Inheritance and mapping of 11 avirulence genes in Phytophthora sojae. Fungal Genet Biol 37: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tyler BM, Forster H, Coffey MD (1995) Inheritance of avirulence factors and restriction fragment length polymorphism markers in outcrosses of the oomycete Phytophthora sojae. Molecular Plant Microbe Interaction 8: 515–523. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chamnanpunt J, Shan WX, Tyler BM (2001) High frequency mitotic gene conversion in genetic hybrids of the oomycete Phytophthora sojae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98: 14530–14535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhat RC, McBlain BA, Schmitthenner AF (1993) The inheritance of resistance to metalaxyl and to fluorophenylalaine in matings of homothallic Phytophthora sojae. Mycological research July 97: 865–870. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamour KH, Mudge J, Gobena D, Hurtado-Gonzales OP, Schmutz J, et al. (2012) Genome sequencing and mapping reveal loss of heterozygosity as a mechanism for rapid adaptation in the vegetable pathogen Phytophthora capsici. Molecular plant-microbe interactions: MPMI 25: 1350–1360. 10.1094/MPMI-02-12-0028-R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vercauteren A, Boutet X, D’hondt L, Van Bockstaele E, Maes M, et al. (2011) Aberrant genome size and instability of Phytophthora ramorum oospore progenies. Fungal genetics and biology: FG & B 48: 537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu J, Diao Y, Zhou Y, Lin D, Bi Y, et al. (2013) Loss of heterozygosity drives clonal diversity of Phytophthora capsici in China. PLoS One 8: e82691 10.1371/journal.pone.0082691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter DA, Buck KW, Archer SA, Van der Lee T, Shattock RC, et al. (1999) The detection of nonhybrid, trisomic, and triploid offspring in sexual progeny of a mating of Phytophthora infestans. Fungal Genet Biol 26: 198–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacGregor T, Bhattacharyya M, Tyler B, Bhat R, Schmitthenner AF, et al. (2002) Genetic and physical mapping of Avrla in Phytophthora sojae. Genetics 160: 949–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gijzen M, Qutob D (2009) Phytophthora sojae and Soybean In: Lamour K, Kamoun S, editors. Oomycete Genetics and Genomics: Diversity, Interactions, and Research Tools: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 303–329. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tyler BM (2007) Phytophthora sojae: root rot pathogen of soybean and model oomycete. Molecular Plant Pathology 8: 1–8. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2006.00373.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dorrance A, Grünwald NJ (2009) Phytophthora sojae: Diversity among and within Populations In: Lamour K, Kamoun S, editors. Oomycete Genetics and Genomics: Diversity, Interactions, and Research Tools: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 197–212. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dorrance AE, Robertson AE, Cianzo S, Giesler LJ, Grau CR, et al. (2009) Integrated Management Strategies for Phytophthora sojae Combining Host Resistance and Seed Treatments. Plant disease: an international journal of applied plant pathology 93: 875–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qutob D, Tedman-Jones J, Dong S, Kuflu K, Pham H, et al. (2009) Copy number variation and transcriptional polymorphisms of Phytophthora sojae RXLR effector genes Avr1a and Avr3a. PLoS ONE 4: e5066 10.1371/journal.pone.0005066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shan WX, Cao M, Dan LU, Tyler BM (2004) The Avr1b locus of Phytophthora sojae encodes an elicitor and a regulator required for avirulence on soybean plants carrying resistance gene Rps1b. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 17: 394–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Na R, Yu D, Chapman BP, Zhang Y, Kuflu K, et al. (2014) Genome re-sequencing and functional analysis places the Phytophthora sojae avirulence genes Avr1c and Avr1a in a tandem repeat at a single locus. PLoS One 9: e89738 10.1371/journal.pone.0089738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Na R, Yu D, Qutob D, Zhao J, Gijzen M (2013) Deletion of the Phytophthora sojae avirulence gene Avr1d causes gain of virulence on Rps1d. Molecular plant-microbe interactions: MPMI 26: 969–976. 10.1094/MPMI-02-13-0036-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yin W, Dong S, Zhai L, Lin Y, Zheng X, et al. (2013) The Phytophthora sojae Avr1d gene encodes an RxLR-dEER effector with presence and absence polymorphisms among pathogen strains. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 26: 958–968. 10.1094/MPMI-02-13-0035-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song T, Kale SD, Arredondo FD, Shen D, Su L, et al. (2013) Two RxLR avirulence genes in Phytophthora sojae determine soybean Rps1k-mediated disease resistance. Molecular plant-microbe interactions: MPMI 26: 711–720. 10.1094/MPMI-12-12-0289-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong S, Yu D, Cui L, Qutob D, Tedman-Jones J, et al. (2011) Sequence variants of the Phytophthora sojae RXLR effector Avr3a/5 are differentially recognized by Rps3a and Rps5 in soybean. PloS one 6: e20172 10.1371/journal.pone.0020172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong S, Yin W, Kong G, Yang X, Qutob D, et al. (2011) Phytophthora sojae avirulence effector Avr3b is a secreted NADH and ADP-ribose pyrophosphorylase that modulates plant immunity. PLoS pathogens 7: e1002353 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dong S, Qutob D, Tedman-Jones J, Kuflu K, Wang Y, et al. (2009) The Phytophthora sojae avirulence locus Avr3c encodes a multi-copy RXLR effector with sequence polymorphisms among pathogen strains. PLoS ONE 4: e5556 10.1371/journal.pone.0005556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dou D, Kale SD, Liu T, Tang Q, Wang X, et al. (2010) Different domains of Phytophthora sojae effector Avr4/6 are recognized by soybean resistance genes Rps4 and Rps6. Molecular plant-microbe interactions: MPMI 23: 425–435. 10.1094/MPMI-23-4-0425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qutob D, Chapman PB, Gijzen M (2013) Transgenerational gene silencing causes gain of virulence in a plant pathogen. Nature communications 4: 1349 10.1038/ncomms2354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gijzen M, Ishmael C, Shrestha SD (2014) Epigenetic control of effectors in plant pathogens. Front Plant Sci 5: 638 10.3389/fpls.2014.00638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kasuga T, Gijzen M (2013) Epigenetics and the evolution of virulence. Trends in microbiology 21: 575–582. 10.1016/j.tim.2013.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Long M, Keen NT, Ribeiro OK, Leary JV, Erwin DC, et al. (1975) Phytophthora megasperma var. sojae: Development of wild-type strains for genetic research. Phytopathology 65: 592–597. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jablonka E, Raz G (2009) Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: prevalence, mechanisms, and implications for the study of heredity and evolution. Q Rev Biol 84: 131–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rechavi O, Houri-Ze'evi L, Anava S, Goh WS, Kerk SY, et al. (2014) Starvation-induced transgenerational inheritance of small RNAs in C. elegans. Cell 158: 277–287. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rechavi O, Minevich G, Hobert O (2011) Transgenerational inheritance of an acquired small RNA-based antiviral response in C. elegans. Cell 147: 1248–1256. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shao C, Li Q, Chen S, Zhang P, Lian J, et al. (2014) Epigenetic modification and inheritance in sexual reversal of fish. Genome Res 24: 604–615. 10.1101/gr.162172.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iwasaki M, Paszkowski J (2014) Epigenetic memory in plants. EMBO J 33: 1987–1998. 10.15252/embj.201488883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelly WG (2014) Transgenerational epigenetics in the germline cycle of Caenorhabditis elegans. Epigenetics Chromatin 7: 6 10.1186/1756-8935-7-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forster H, Tyler BM, Coffey MD (1994) Phytophthora sojae races have arisen by clonal evolution and by rare outcrosses. Molecular Plant Microbe Interaction 7: 780–791. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dobrowolski MP, Tommerup IC, Blakeman HD, O'Brien PA (2002) Non-Mendelian inheritance revealed in a genetic analysis of sexual progeny of Phytophthora cinnamomi with microsatellite markers. Fungal Genet Biol 35: 197–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Francis DM, Gehlen MF, St Clair DA (1994) Genetic variation in homothallic and hyphal swelling isolates of Pythium ultimum var. ultimum and P. utlimum var. sporangiferum. Molecular plant-microbe interactions: MPMI 7: 766–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chandler V, Alleman M (2008) Paramutation: epigenetic instructions passed across generations. Genetics 178: 1839–1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rutherford FS, Ward EWB, Buzzell RI (1985) Variation in virulence in successive single-zoospore propagations of Phytophthora megasperma f.sp. glycinea. Phytopathology 75: 371–374. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raffaele S, Farrer RA, Cano LM, Studholme DJ, MacLean D, et al. (2010) Genome evolution following host jumps in the Irish potato famine pathogen lineage. Science (New York, NY) 330: 1540–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Judelson HS, Tani S (2007) Transgene-induced silencing of the zoosporogenesis-specific NIFC gene cluster of Phytophthora infestans involves chromatin alterations. Eukaryotic cell 6: 1200–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vetukuri RR, Asman AK, Tellgren-Roth C, Jahan SN, Reimegard J, et al. (2012) Evidence for small RNAs homologous to effector-encoding genes and transposable elements in the oomycete Phytophthora infestans. PloS one 7: e51399 10.1371/journal.pone.0051399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whisson S, Vetukuri R, Avrova A, Dixelius C (2012) Can silencing of transposons contribute to variation in effector gene expression in Phytophthora infestans? Mobile genetic elements 2: 110–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vetukuri RR, Asman AK, Jahan SN, Avrova AO, Whisson SC, et al. (2013) Phenotypic diversification by gene silencing in Phytophthora plant pathogens. Commun Integr Biol 6: e25890 10.4161/cib.25890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vetukuri RR, Avrova AO, Grenville-Briggs LJ, Van West P, Soderbom F, et al. (2011) Evidence for involvement of Dicer-like, Argonaute and histone deacetylase proteins in gene silencing in Phytophthora infestans. Mol Plant Pathol 12: 772–785. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00710.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dorrance AE, Berry SA, Anderson TR, Meharg C (2008) Isolation, storage, pathotype characterization, and evaluation of resistance for Phytophthora sojae in soybean. Plant health progress: 10.1094/PHP-2008-0118-1001-DG [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tyler BM, Tripathy S, Zhang XM, Dehal P, Jiang RHY, et al. (2006) Phytophthora genome sequences uncover evolutionary origins and mechanisms of pathogenesis. Science 313: 1261–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martin FN, Bensasson D, Tyler BM, Boore JL (2007) Mitochondrial genome sequences and comparative genomics of Phytophthora ramorum and P. sojae. Current Genetics 51: 285–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

Small RNA sequence data for all samples described in this study are available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive, Bioproject PRJNA300858.