Abstract

For two months between May and July 2015, a nationwide outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) occurred in Korea. On June 3, 2015, the Korean Society for Laboratory Medicine (KSLM) launched a MERS-CoV Laboratory Response Task Force (LR-TF) to facilitate clinical laboratories to set up the diagnosis of MERS-CoV infection. Based on the WHO interim recommendations, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of United States guidelines for MERS-CoV laboratory testing, and other available resources, the KSLM MERS-CoV LR-TF provided the first version of the laboratory practice guidelines for the molecular diagnosis of MERS-CoV to the clinical laboratories on June 12, 2015. The guidelines described here are an updated version that includes case definition, indications for testing, specimen type and protocols for specimen collection, specimen packing and transport, specimen handling and nucleic acid extraction, molecular detection of MERS-CoV, interpretation of results and reporting, and laboratory safety. The KSLM guidelines mainly focus on the molecular diagnosis of MERS-CoV, reflecting the unique situation in Korea and the state of knowledge at the time of publication.

Keywords: Guidelines, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, Molecular diagnosis, Outbreak

INTRODUCTION

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is a viral respiratory disease caused by a novel coronavirus (MERS-CoV) that was first identified in Saudi Arabia in 2012 [1]. No MERS cases were reported in Korea until May 20, 2015 when the first Korean MERS case was identified in a 68-yr-old man returning from the Middle East. Since then a total of 186 confirmed cases have been reported in Korea as of Oct 2, 2015 [2,3].

On June 3, 2015, the Korean Society for Laboratory Medicine (KSLM) launched a MERS-CoV Laboratory Response Task Force (LR-TF) to facilitate clinical laboratories to set up the diagnosis of MERS-CoV infection. Although laboratory guidelines or resources for the molecular diagnosis of MERS-CoV had been provided by several international authoritative bodies [4,5], the Korean version of guideline was required in the unexperienced situation of the nationwide outbreak, which developed rapidly by intra-hospital and inter-hospital spread of an imported deadly virus. This outbreak was beyond national capacity of laboratory preparedness for emerging infectious diseases. Therefore, the KSLM MERS-CoV LR-TF decided to provide the clinical laboratories with the laboratory practice guidelines of national standard for the molecular diagnosis of MERS-CoV. On behalf of the Central MERS-CoV Control Office in Korea, organized by the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare (KMHW), the first version of the KSLM laboratory practice guidelines was issued on June 12, 2015.

This updated version of the KSLM laboratory practice guidelines for the molecular diagnosis of MERS-CoV is based on interim recommendations for MERS-CoV laboratory testing by the WHO [4], the laboratory testing guidelines for MERS-CoV by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of United States (US CDC) [5], and other available resources [6,7,8].

The guidelines provided here focus on the molecular diagnosis of MERS-CoV from case definition to interpretation and reporting as well as laboratory safety.

CASE DEFINITION OF MERS-CoV INFECTION

The WHO, US CDC, and Saudi Arabia each has its own case definitions according to the purpose of use. WHO case definitions are for classification and reporting [9]; as such, they should not be used for recommendations of when and whom to test. The case definitions of the US CDC are used to classify patients who should be evaluated for MERS-CoV infection in consultation with state and local health departments [10]. Saudi Arabia also uses its case definitions for surveillance purposes [7]. The following case definitions are for classification and reporting to the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC).

Confirmed case

A person with laboratory confirmation of MERS-CoV infection by KCDC is regarded as a confirmed case irrespective of clinical signs and symptoms. Detection of viral nucleic acid by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) is the method of choice for laboratory confirmation. Detailed protocols for rRT-PCR and interpretation of the results are described later in these guidelines. Although seroconversion assays were not used in the 2015 Korean outbreak, serological confirmation of a case requires the demonstration of seroconversion in two serum samples, ideally taken at least 14 days apart, on the basis of enzyme immunoassay or immunofluorescent assay as a screening and a neutralization assay.

Suspect case

A person with febrile acute respiratory illness of any severity plus either a history of travel to the Middle East or a direct epidemiological link with a confirmed MERS-CoV case within 14 days before symptom onset is regarded as a MERS-CoV suspect case. The Middle East countries include Bahrain, Iraq, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Yemen. A direct epidemiological link with a confirmed MERS-CoV case showing relevant symptoms includes: with or without adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) plus one of 1) staying or living in the same room with a confirmed case; 2) healthcare-associated exposure that includes providing care for MERS-CoV cases; 3) working with healthcare workers infected with MERS-CoV; and/or 4) direct contact with the respiratory secretion of confirmed cases.

Probable case

In addition to the case definitions of confirmed and suspect cases, the KSLM MERS-CoV LR-TF members agree that a case definition for a "probable case" is needed. A probable case can be defined as a suspect case with negative, indeterminate, or equivocal rRT-PCR results. In addition, an individual with preliminary positive rRT-PCR results from clinical laboratories but without confirmed results by KCDC can be defined as a probable case. Repeat testing for MERS-CoV is recommended for probable cases.

INDICATIONS FOR TESTING

The KMHW approved the emergency use of rRT-PCR assays for MERS-CoV diagnosis in clinical laboratories with KSLM guarantee of good laboratory practice from June 6, 2015 to the end of the outbreak. The KMHW defined the following indications to go for a MERS-CoV rRT-PCR test: 1) confirmation of a suspect case, 2) screening for a case with a direct epidemiological link, 3) differential diagnosis of a patient with fever and community-acquired pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome, and/or 4) criteria for releasing confirmed cases from quarantine. The KSLM recommends the testing for other respiratory pathogens such as influenza viruses, parainfluenza viruses, and respiratory syncytial virus, but emphasizes that there should not be any delay in testing for MERS-CoV because of those testing [4].

SPECIMEN TYPE AND PROTOCOLS FOR SPECIMEN COLLECTION

Lower respiratory specimens such as sputum, tracheal aspirates, and bronchoalveolar lavage are preferred for the detection of MERS-CoV; however, collection of upper respiratory specimens is recommended in addition to lower respiratory specimens whenever possible (Table 1). Specimen collection is guided that nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs are collected from the nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal walls, respectively, not just from the nostril or mouth. Nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs could be placed in the same viral transport medium. Synthetic fiber flocked swabs with plastic shafts should be used to increase virus yield. Calcium alginate swabs or swabs with wooden shafts are not recommended because they may contain substances that inactivate some viruses and inhibit PCR reactions. In asymptomatic individuals, induced sputum or forced coughing may help collect lower respiratory tract specimens. The rRT-PCR of serum samples can be helpful for detecting MERS-CoV, but these assays are not recommended for the routine diagnostic process in MERS-CoV outbreaks.

Table 1. Specimen types, sample containers, and transport conditions for molecular detection of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV).

| Type of specimen | Container and transport media | Transport condition | Category of potentially infectious substances | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower respiratory tract | Sputum | Sterile screw-capped container | 4℃ | Category B |

| Bronchoalveolar lavage | Sterile screw-capped container | If MERS-CoV test cannot be performed within 72 hr, freeze and transfer on dry ice | ||

| Tracheal aspirate | Sterile screw-capped container | |||

| Biopsy or autopsy sample | Virus transport medium or sterile normal saline tube for cell culture | |||

| Upper respiratory tract | Nasopharyngeal aspirate | Sterile screw-capped container | ||

| Combined nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swab* | Universal transport media | |||

*Combined nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab: both nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs should be placed in the same vial to increase viral load. Swabs specifically designed for viral testing should be used (flocked synthetic fiber swabs with plastic shaft). Calcium alginate swabs or swabs with wooden shafts should be avoided.

While serological testing is impractical for clinical purposes during MERS-CoV outbreaks, it has incomparable importance for epidemiologic investigations. On the basis of WHO interim recommendations [4], serological testing for MERS-CoV can be used to identify confirmed MERS cases that can be reported under the International Health Regulations, to survey population-based seroprevalence and to investigate past exposures. Because a total of 16,693 people were self-quarantined owing to contact history with confirmed MERS-CoV cases, investigation of seroprevalence in this population is necessary in order to understand the epidemiology and pathophysiology of MERS-CoV infection [2]. It is recommended that serum samples be collected during the acute stage of the disease, preferably during the first week after illness onset and again during convalescence, at least 14 to 21 days after the acute stage sample was collected. If the acute stage sampling is missed, it should be collected at least 14 days after the onset of symptoms [4,11].

All specimen types for routine testing from symptomatic confirmed/ suspect/probable cases should be collected by trained healthcare workers wearing PPE. In addition, further precautions for infection control and prevention in hospitals should be followed when exposure to aerosols such as tracheal intubation, bronchoalveolar lavage, and expectoration is expected as below.

1. Indications for additional precautions: expectoration of sputum, tracheal aspiration, bronchoscopy, intubation, and extubation.

2. Personal protection

- Restrict the number of healthcare workers in the room to avoid unnecessary exposure.

- All healthcare workers should wear PPE, including N95 masks, gloves, long-sleeved gowns, and eye protection equipment such as goggles or face shields.

- Use hand hygiene before and after patient contact and after PPE removal.

3. Environmental control

- An isolation room with a ventilation system that generates negative pressure is recommended. If unavailable, a single room ventilated with 6 to 12 air changes per hour (through forced ventilation duct system) can be used.

- After procedures, the room should be cleaned and evacuated for 30 minutes (in the case of 12 air changes).

- Access to the room during procedures should be minimized.

SPECIMEN PACKING AND TRANSPORT

Double package systems can be used for transportation within an institution. All specimens must be packaged in a leak-proof plastic primary container with a screw cap. Primary containers that are decontaminated with 70% alcohol swabs and placed in a clear re-sealable zipper bag with absorbents must be packaged with a secondary container for transfer. Accurate labeling or the attachment of barcodes, including at least two patient identifiers on all specimens as well as on the package, is essential to avoid specimen mix-ups and contamination.

For transportation outside an institution, triple package systems must be used according to the KCDC guidelines [12]. Similar to within-an-institution transfer, all specimens must be packed in double containers. The secondary containers are packed with the associated information sheets such as request forms or information forms in the tertiary container, which is consistent with infectious substance shipping guidance by KCDC [15].

SPECIMEN HANDLING AND NUCLEIC ACID EXTRACTION

All specimens should be stored at 2–8℃ up to 72 hr before nucleic acid extraction. If nucleic acid extraction cannot be performed within 72 hr after collection, specimens should be stored at -70℃ or lower as soon as possible after collection. MERS-CoV RNA should be extracted by using appropriate manual or automated nucleic acid extraction methods. For example, the QIAamp DSP Viral RNA Mini kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany) is one of the most widely used manual extraction methods, and the NucliSENS easyMAG (bioMérieux, Durham, NC, USA), MagNA Pure 96 System (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), and QIAcube (QIAGEN) are commonly used automated nucleic extraction methods. Nucleic acid extraction from sputum, tracheal aspirates, bronchoalveolar lavage, nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swabs, or blood should be performed according to the manufacturers' instructions. RNA samples should be stored at -70℃ or lower.

MOLECULAR DETECTION OF MERS-CoV RNA

rRT-PCR is recommended for the molecular detection of MERS-CoV RNA. Laboratory confirmation of MERS-CoV infection requires either a positive rRT-PCR result for at least two specific genomic targets or a single positive target with sequencing of a second target. The upstream of the E protein gene (upE), open reading frame 1a (ORF1a), open reading frame 1b (ORF1b), and N genes are common targets for rRT-PCR, while RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), ORF1b, and N genes are targets for sequencing.

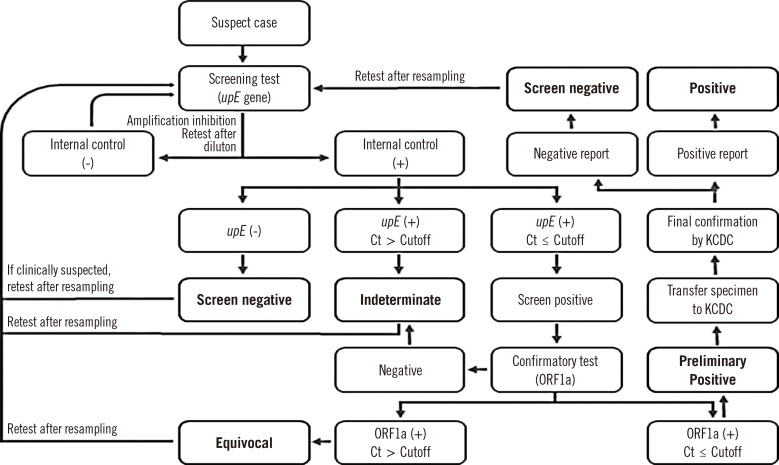

Practically, rRT-PCR assays targeting upE are recommended for screening (Fig. 1). If the upE screening assay is positive, an independent, confirmatory rRT-PCR assay targeting ORF1a should be performed. Laboratory developed tests and commercial kits for rRT-PCR assay should be used with provision of positive control and validation by LR-TF.

Fig. 1. Laboratory process for the diagnosis of Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus infection in Korea.

Abbreviations: upE, upstream of the E gene; ORF1a, open reading frame 1a; ORF1b, open reading frame 1b; Ct, cycle threshold; KCDC, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A heterologous internal control to identify possible rRT-PCR inhibition and to confirm the integrity of the reagents of the kit is essential. Each run of rRT-PCR reaction should include both positive and negative controls in parallel. It is mandatory for all clinical laboratories to participate in the external quality control assessment organized by the KSLM LR-TF.

RESULTS INTERPRETATION AND REPORTING

The first step of interpretation of MERS-CoV rRT-PCR is verification of the internal control (Fig. 1). Negative reactions in the internal control indicate a failure of the amplification process owing to either the presence of PCR inhibitors or other reasons. In this case, retesting the same sample is required after processing it to eliminate the inhibitory effect, including re-extraction of the nucleic acids or dilution of the extracted nucleic acids. When the internal control is properly amplified, the results can be classified as screen-negative, -indeterminate, or -positive according to the cycle threshold (Ct) values and whether the upE gene was amplified. Screen-positive specimens should be confirmed by amplification of ORF1a or other targets. When indeterminate or equivocal results are obtained in suspect cases, the results should be reported immediately to infection control units in each hospital.

A series of negative results in the cases which have definite contact history should not rule out MERS-CoV infection, and factors that can cause false negatives such as poor specimen quality, too early or late stage specimens, inappropriate handling or specimen transport, and inherent testing problems should be investigated by obtaining an additional specimen (especially a lower respiratory specimen), by the verification of an internal control, or by retesting the sample at another facility for confirmation.

LABORATORY SAFETY

Diagnostic laboratory work and rRT-PCR analysis on clinical specimens from suspect, confirmed, or probable cases of MERS-CoV should be conducted in clinical laboratories with BSL-2 facilities [13,14]. Appropriate PPE should be worn, and all technical procedures should be performed in a way that minimizes the formation of aerosols and droplets in class II biosafety cabinets with current certification. After completion of daily work, the workspace is cleaned with 70% alcohol, and all PPEs are removed. Hand hygiene is necessary whenever PPEs are removed and before exit from laboratories. All wastes and remaining specimens should be discarded by legislative regulation of medical wastes, but clinical specimens positive for MERS-CoV rRT-PCR should be discarded after sterilization such as autoclaving. The dilution or aliquot procedures of the potentially infectious substances, including the procedures for bacterial or fungal cultures, should be performed within a biological safety cabinet.

CONCLUSIONS

These guidelines reflect our current understanding of MERS-CoV at the time of publication and the unique situation of the Korean MERS-CoV outbreak. When a clinical laboratory is to perform molecular testing for MERS-CoV, each laboratory should prepare its own protocols according to these guidelines and other available resources. In addition, laboratory layouts and facilities that are not covered in these guidelines should be checked in order to prevent contamination during PCR procedures and also to provide a safe environment for all laboratory staff.

In conclusion, KSLM has established the practice guidelines for the molecular diagnosis of MERS-CoV during an outbreak in Korea in 2015. To prepare laboratory response to prevent and control public health crisis by emerging infectious diseases in future, practice guidelines for laboratory diagnosis of other possible agents should be prepared with preemptive risk assessment in cooperation with public and private sectors.

Acknowledgments

This work contained valuable feedback from many laboratory physicians who participated in molecular detection of MERS-CoV during MERS outbreak in Korea in 2015.

Footnotes

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

This KSLM guideline was the part of the official MERS practice guideline of Central MERS-CoV Control Office published online through the homepage of The Korean Society of Infectious Diseases (http://www.ksid.or.kr/) during the outbreak.

References

- 1.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Central MERS-CoV Control Office. MERS Statistics. [Updated on Oct 2, 2015]. http://www.mers.go.kr/mers/html/jsp/main.jsp.

- 3.WHO. MERS-CoV in Republic of Korea at a glance as of 29 July 2015. http://www.wpro.who.int/outbreaks_emergencies/wpro_coronavirus/en/

- 4.WHO. Laboratory testing for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. Interim guidance. [Updated on June 2015]. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/mers-laboratory-testing/en/

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Laboratory Testing for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) [Updated on June 25, 2014]. http://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/lab/lab-testing.html.

- 6.Corman Corman, Müller MA, Costabel U, Timm J, Binger T, Meyer B. Assays for laboratory confirmation of novel human coronavirus (hCoV-EMC) infections. Euro Surveill. 2012;17(49):pii:20334. doi: 10.2807/ese.17.49.20334-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Command and Control Center, Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The case definition for MERS-CoV infections approved by the ministry of health. [Updated on Jun 2015]. http://www.moh.gov.sa/en/CCC/Regulations/Case%20Definition.pdf.

- 8.Corman VM, Eckerle I, Bleicker Bleicker, Zaki A, Landt O, Eschbach-Bludau M. Detection of a novel human coronavirus by real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. Euro Surveill. 2012;17(39):pii:20285. doi: 10.2807/ese.17.39.20285-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO. Middle Ease respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Case definition for reporting to WHO. Interim case definition as of 14 July 2015. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/case_definition/en/

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim patient under investigation (PUI) guidance and case definitions. [Updated on Dec 2015]. http://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/case-def.html.

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidelines for collecting, handling, and testing clinical specimens from patients under investigation (PUIs) for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – Version 2.1. [Updated on Jun 16, 2015]. http://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html.

- 12.Korea Centers for Disese Control and Prevention. Instructions for the safe transport of infectious substances. 2nd ed. [Updated in 2015]. http://www.cdc.go.kr/CDC/contents/CdcKrContentView.jsp?cid=26529&menuIds=HOME001-MNU1133-MNU1161-MNU1517.

- 13.WHO. Novel coronavirus 2012: Interim recommendations for laboratory biorisk management. [Updated on Oct 31, 2012]. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/NovelCoronavirus2012_InterimRecommendationsLaboratoryBiorisk/en/

- 14.WHO. WHO Laboratory Biosafety Manual. 3rd ed. Geneva: WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The guideline for safe transportation of infectious substances (2013) [Updated on Apr 2014]. http://www.cdc.go.kr/CDC/notice/CdcKrTogether0302.jsp?menuIds=HOME001-MNU1154-MNU0004-MNU0088&cid=26027.